Intervenciones para el tratamiento de la enfermedad de las alturas aguda

Información

- DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009567.pub2Copiar DOI

- Base de datos:

-

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Versión publicada:

-

- 30 junio 2018see what's new

- Tipo:

-

- Intervention

- Etapa:

-

- Review

- Grupo Editorial Cochrane:

-

Grupo Cochrane de Atención crítica y de emergencia

- Copyright:

-

- Copyright © 2018 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Cifras del artículo

Altmetric:

Citado por:

Autores

Contributions of authors

Daniel Simancas‐Racines (DSR), Dimelza Osorio (DO), Juan VA Franco (JVAF), Ingrid Arevalo‐Rodriguez (IAR), Yihan Xu (YX), Ricardo Hidalgo (RH), Arturo Martí Carvajal (AMC) (see Acknowledgements).

Conceiving the review: DSR and AMC

Designing the review: DSR and AMC

Co‐ordinating the review: DO

Screening search results: DS, DO

Organizing retrieval of papers: DO

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria: DSR, DO, IAR, YX

Appraising quality of papers: DSR, DO, JVAF, IAR, YX

Abstracting data from papers: DSR, DO, JVAF, IAR, YX

Writing to authors of papers for additional information: DO, JVAF

Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies: DSR, DO

Data management for the review: DO, JVAF

Entering data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5): DSR, DO, JVAF

RevMan 5 statistical data: DSR, DO, JVAF

Other statistical analysis not using RevMan 5: none

Double entry of data: DSR, DO, JVAF

Interpretation of data: DSR, DO, JVAF, IAR, YX

Statistical inferences: DSR, DO, JVAF, IAR, YX

Writing the review: DSR, DO, JVAF, IAR, YX, RH

Providing guidance on the review: DSR, DO, JVAF, IAR, RH

Securing funding for the review: DSR, IAR, RH

Performing previous work that was the foundation of the present study: Arturo Martí‐Carvajal, Alejandro G Gonzalez Garay

Guarantor for the review (one author): DSR

Persons responsible for reading and checking review before submission: DSR, DO, JVAF, IAR, YX

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud Eugenio Espejo, Universidad Tecnológica Equinoccial, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic

External sources

-

Iberoamerican Cochrane Center, Spain.

Academic.

-

Cochrane Anaesthesia, Critical and Emergency Care Group, Denmark.

Academic

Declarations of interest

Daniel Simancas‐Racines: no conflict of interest.

Dimelza Osorio: no conflict of interest.

Juan VA Franco: no conflict of interest.

Ingrid Arevalo‐Rodriguez: no conflict of interest.

Yihan Xu: no conflict of interest.

Ricardo Hidalgo: no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to Professor Arturo Martí‐Carvajal (protocol author) for planning the review and writing the protocol (Martí‐Carvajal 2012). We also would like to thank Mike Bennett (content editor), Cathal Walsh (statistical editor), Alex Wright and Edward T Gilbert‐Kawai (peer reviewers), Matiram Pun (consumer referee), and Andrew Smith (sign‐off editor) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review. Our thanks also to Jane Cracknell for all her support and advice during the editorial process.

Daniel Simancas‐Racines is a PhD candidate at the Department of Pediatrics, Gynecology and Obstetrics, and Preventive Medicine, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain.

Version history

| Published | Title | Stage | Authors | Version |

| 2018 Jun 30 | Interventions for treating acute high altitude illness | Review | Daniel Simancas‐Racines, Ingrid Arevalo‐Rodriguez, Dimelza Osorio, Juan VA Franco, Yihan Xu, Ricardo Hidalgo | |

| 2012 Jan 18 | Interventions for treating high altitude illness | Protocol | Arturo J Martí‐Carvajal, Daniel Simancas‐Racines, Ricardo Hidalgo | |

Differences between protocol and review

We made the following changes to the protocol (Martí‐Carvajal 2012).

-

-

The list of authors has changed since the protocol was published. Martí‐Carvajal AJ is not present and Franco VJA, Arevalo‐Rodriguez I and Xu Y were included.

-

The background has been modified: some text related to the history of the concept of HAI has been deleted; and more recent references have been included. We also provided more details on how the interventions might work.

-

In the section Types of studies: in the protocol it was mentioned that "we will exclude quasi‐randomized studies and prospective observational studies for evaluating clinical effectiveness. However, we will consider these studies for reports on adverse events". We did not include quasi‐randomized studies and prospective observational studies for reports on adverse events because the methodology to do this was not detailed in the protocol. However, we collected and analysed all information regarding adverse events from included studies.

-

In the section Types of interventions: in the protocol "frusemide" is listed as an intervention, which is the previous chemical denomination of the loop diuretic. Since the current denomination of this intervention is "furosemide" (Pubchem ‐ Furosemide 2017), we used this denomination throughout the review.

-

In the section Types of outcome measures: we have included the definition of the outcome 'Complete relief of acute mountain sickness symptoms' by adding the following text: "defined as the complete absence of the acute mountain sickness symptoms by the end of the study".

-

This outcome was considered as a binary outcome as it was originally stated in the protocol at the section Measures of treatment effect.

-

In the section Electronic searches: the Chinese database Wanfang (Wanfangdata.com) was included in the search. This decision was taken by the review authors since several studies taking place in the Tibet and other areas of Asia may not appear in CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, LILACS, ISI Web of Science and CINAHL.

-

In the section Searching other resources: we added the date of search of the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; search date 24 February 2017) and of the principal investigators (3 March 2017). We added the following text after the dates: "Unpublished trials will be considered in updating of this review".

-

In the section Measures of treatment effect: the phrases "The unit of analysis will be the patient" and "We will collect and analyse a single measurement for each outcome from each participant" included in the protocol in the section of Measures of treatment effect were moved to the section Unit of analysis issues. We have considered adverse events (stated in the outcomes) as a synonym of safety. We have rewritten this section including the word 'safety' in brackets next to the words 'adverse events' that is the outcome defined for the review.

-

For analysis of continuous outcomes, we used standardized mean differences instead of mean differences, taking into account that included studies used different scales to measure the improvement of HAI symptoms. This analysis was used to present the findings about reduction in illness severity for acetazolamide versus placebo.

-

In the sections summary of findings Table for the main comparison and summary of findings Table 2 and GRADE: we have considered adverse events (stated in the outcomes) as a synonym of safety. We have rewritten this section including the word 'safety' in brackets next to the words 'adverse events' that is the outcome defined for the review. We also expanded the description on how we developed the 'Summary of findings' tables, and on how we took them into account to appraise the overall quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on the outcomes we considered.

-

In Appendix 5: the search strategy in the WHO International Trials Registry Portal has been modified in order to improve sensitivity. Before: advanced search: high‐altitude pulmonary oedema (in the title field). After: altitude Sickness OR Altitude illness OR acute mountain sickness OR High‐altitude oedema OR high‐altitude oedema (in the title field).

-

Due to scarcity of evidence we were unable to carry out the following methods:

-

we planned to present the results of continuous outcomes as summary standardized mean difference with 95% CI. Instead, we presented the standardized mean difference for pooled results and the mean difference for individual studies.

-

exploration of heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses.

-

assessment of reporting biases.

-

use of fixed‐effect and random‐effects models.

-

subgroup analysis

-

-

Keywords

MeSH

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) Keywords

- Acetazolamide [therapeutic use];

- Acute Disease;

- Altitude Sickness [*therapy];

- Amines [therapeutic use];

- Anticonvulsants [therapeutic use];

- Atmospheric Pressure;

- Cyclohexanecarboxylic Acids [therapeutic use];

- Dexamethasone [therapeutic use];

- Gabapentin;

- Glucocorticoids [therapeutic use];

- Hypertension, Pulmonary [therapy];

- Magnesium [therapeutic use];

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic;

- gamma‐Aminobutyric Acid [therapeutic use];

Medical Subject Headings Check Words

Adolescent; Adult; Humans;

PICO

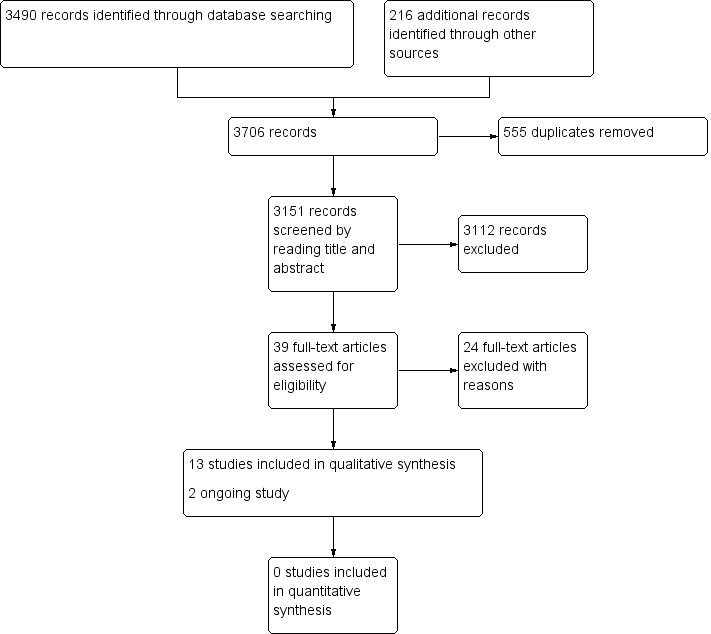

Study flow diagram.

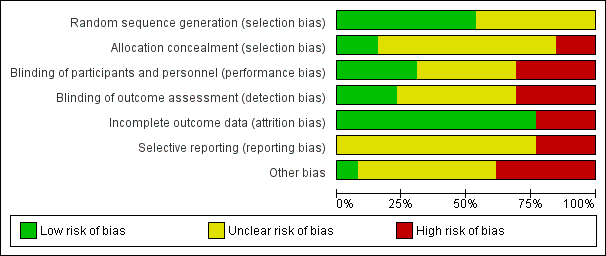

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

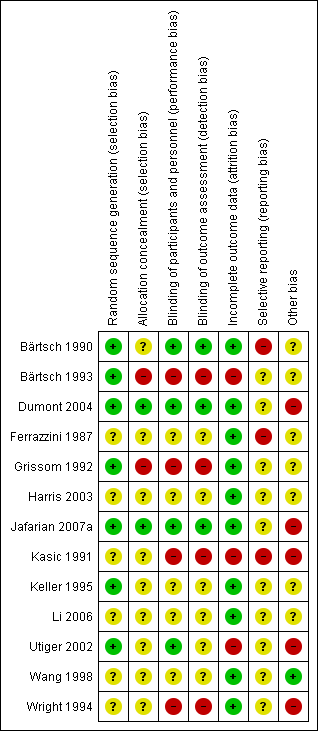

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Acetazolamide versus placebo, Outcome 1 AMS symptoms (standardized).

| Non‐pharmacological interventions for treating acute high altitude illness | ||||||

| Patient or population: people suffering from high altitude illness | ||||||

| Outcomes and intervention | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with various interventions | Risk with non‐pharmacological interventions | |||||

| All‐cause mortality | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Complete relief of AMS symptoms | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported |

| Reduction in symptom score severity at 12 hours (Clinical score: ranged from 0 to 11 (worse)) Intervention: Simulated descent of 193 millibars versus 20 millibars | The mean score in the control group was 3.1 | The mean score in the intervention group was 2.5 | 0.6 points lower with intervention | 64 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| Adverse effects during treatment Intervention: Hyperbaric chamber/ 160 millibars versus supplementary oxygen | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | Nil | 29 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1 Quality of evidence downgraded by two levels due to serious risk of bias (performance bias (blinding was not specified), attrition bias and selective reporting bias) and serious imprecision (optimal information size criteria not achieved) | ||||||

| Pharmacological interventions for treating acute high altitude illness | |||||||

| Patient or population: people suffering from high altitude illness | |||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | ||

| Risk with various interventions | Risk with pharmacological interventions | ||||||

| All‐cause mortality | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not reported | |

| Complete relief of AMS symptoms (12 to 16 hours after treatment) Scale used: Acute Mountain Sickness score (ranged from 0 to 9 (worse)) | Dexamethasone versus placebo | 0 per 1000 | 471 per 1000 | No estimable | 35 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| Reduction in symptom score severity Time of measurement: 1 to 48 hours after treatment, end of treatment Scale of measurement: Self‐administered AMS questionnaires (ranged from 0 to 90 (worse)), AMS Symptom Questionnaire (ranged from 0 to 22 (worse)), Acute Mountain Sickness score (ranged from 0 to 9 (worse)), HAH Visual analogue score (VAS) (range no stated), Lake Louise Score (from 0 to 15 (worse)), | Acetazolamide versus placebo | Standardized Mean Difference 1.15 lower | 25 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |||

| Dexamethasone versus placebo | Mean change from baseline: 0.4 units | Mean change from baseline: 4.1 units | Difference of 3.7 units (reported by trial authors) | 35 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | ||

| Gabapentin versus placebo | Mean VAS score: 4.75 | Mean VAS score: 2.92 | Not stated | 24 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| Magnesium versus placebo | Mean score: 10.3 units | Mean score: 9 units | Not stated | 25 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| Adverse effects Time of measurement: 1 to 48 hours after treatment, end of treatment Scale of measurement:not stated | Acetazolamide versus placebo | No reported | 0 per 1000 | Not estimable | 25 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| Gabapentin versus placebo | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | Not stated | 24 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| Magnesium sulphate versus placebo | 77 per 1000 | 750 per 1000 | Not stated | 25 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||||

| 1 Quality of evidence downgraded by two levels due to very serious risk of bias (multiple unclear biases and high risk of selective reporting bias) 2 Quality of evidence downgraded by two levels due to serious risk of bias (selection bias) and serious inconsistency (I² = 58%). 3 Quality of evidence downgraded by one level due to serious risk of bias (selection, performance and detection bias). 4 Quality of evidence downgraded by two levels due to serious risk of bias and serious imprecision. | |||||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 AMS symptoms (standardized) Show forest plot | 2 | 25 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.15 [‐2.56, 0.27] |