Workplace interventions for smoking cessation

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [author‐defined order]

| Methods | Country:USA | |

| Participants | 36 employees and spouses (25 women and 11 men) | |

| Interventions | Group therapy | |

| Outcomes | Self report of smoking status and consumption at 6m, with CO validation and cigarette butt weight. | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | Analyses were conducted on non‐abstinent subjects at end of treatment, to assess reduction efficacy. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 63 smokers | |

| Interventions | In the initial study, 48 subjects of the total (N = 63) used, were assigned to one of three treatments: | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported cessation at 3m and 6m, with saliva thiocyanate confirmation at 3m only. | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | Participants: 136 smokers from 8 worksites. Site size ranged from 50 ‐ 380 | |

| Interventions | Evaluates the incremental effectiveness of competition and relapse prevention training in the context of a multicomponent cessation programme | |

| Outcomes | Cessation at 6m | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | The competition incentive was conducted within each intervention worksite, rather than between the worksites. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 233 smokers in 21 group discussion worksites, 192 in 22 non‐group work sites. | |

| Interventions | All participants were given self‐help manuals by company co‐ordinators and instructed to view the televized segments | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12m (multiple PP) | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 159 smokers (av. age 43, 66% male, av.cpd 25) with preference for group programme or no preference. | |

| Interventions | Group therapy preference: | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12m (single PP) | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | Group programmes were held away from worksite in non‐work hours. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 419 smokers who participated in the worksite programmes, 206 Group, 213 No Group conditions. | |

| Interventions | 1. 6 x twice‐weekly group meetings to coincide with the 3w television series, then monthly meetings for a year. Abstinent smokers and 5 of their family and 5 co‐workers entered for a lottery at the final group meeting and 12m follow up. | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence from end of programme to 24m | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | This study featured monthly booster sessions and monetary incentives for abstainers, as a development of the design of the first De Paul study | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | Intervention worksites (I): 1885 workers, | |

| Interventions | The 3m intervention included consultation for employers on the adoption of a non‐smoking policy, training for nonsmokers to provide assistance to smokers attempting to quit, and cessation classes for smokers | |

| Outcomes | Quit rate, self‐reported ( an attempt was made to collect saliva samples for analysis for cotinine). Baseline survey of all employees was conducted 9m before intervention, companies then randomized, then 3m intervention period, 1m and 6m after the completion of intervention. | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | Analyses were by individuals for some outcomes, although randomization was by worksite. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 844 smokers recruited; 289 Self Help (SH), 281 Incentives (I), 283 Group (G). | |

| Interventions | Worksite interventions timed to coincide with a mass media intervention consisting of a week‐long smoking cessation series on TV, and a complementary newspaper supplement. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 12m | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | Discussion section includes some cost‐benefit analysis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: Belgium | |

| Participants | 344 quitters, abstinent for at least 1m at end of 3m X 7 cessation programme including group therapy and NRT. | |

| Interventions | 1. Relapse Prevention (RP). 10 sessions inc group discussion and role play led by professional counsellor | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence for 9m from start of RP programme. | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | All participants for this study had achieved abstinence after a 3m group and NRT programme. This is a relapse prevention study, rather than cessation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Country: Japan | |

| Participants | 53 volunteer smokers | |

| Interventions | 1. Intervention group received intensive education (i.e. the effect of smoking on health, the beneficial aspects of quitting smoking, how to stop smoking and how to deal with the withdrawal symptoms) for 5m, group lectures (twice) and individual counselling (three times). | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported and validated using expired air CO concentration. | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | Other outcomes included predictors of cessation success. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: Germany | |

| Participants | 79 workers, mean age 40, 58% male, mean cpd 24, mean FTND score 5. | |

| Interventions | 6x90min sessions over 8 wks, group counselling + NRT if wanted. First 2 sessions same, then: 1. SB: psycho‐educational, self‐monitoring, environmental cue control, problem‐solving, behavioural control strategies, operant conditioning, social support. 2. RP: functional analysis of high‐risk situations, planning for them, coping strategies, self‐monitoring, noting triggers. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported CA and PPA at 1m and 12m. | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | 12m non‐responders were phoned for smoking status. | |

| Methods | Country: Turkey | |

| Participants | 200 workers (425 smokers completed baseline questionnaire); 100 in each group, matched on age, education, working periods and amount smoked. Intervention and control groups worked different shifts. All male workforce, mean age 29.3, 81.7% married, 44.5% attended high school. Prevalence 65.9% smokers, 6.8% ex‐smokers. | |

| Interventions | 3‐wk 7‐step programme, based on stages of change model, and ALA programme. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome was movement through stages of change, but 6m cessation rate also reported. PPA self‐report, no verification. | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: GROUPS | |

| Notes | Reported as no attrition or losses to follow up. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | N/A |

| Methods | Country: Belgium | |

| Participants | Participants: 16,230 men aged 40‐59 (83.7% of eligible men) | |

| Interventions | 1. Intervention: All screened for height, weight, cholesterol, smoking, BP, ECG, personality and psychological testing. Top 20% at risk counted as the 'high risk' group, who received 6‐monthly individual physician counselling. Complete cessation was encouraged, but pipes or cigars allowed if necessary. Advice booklet also supplied. All smokers of 5 or more cpd received written advice to quit.. Environmental components included anti‐smoking posters and a factory conference on dangers of tobacco. | |

| Outcomes | 7‐day PP at 2 yrs follow up. | |

| Type of intervention | 1. Intensive behavioural: INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING | |

| Notes | This trial was added to the 2005 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: France | |

| Participants | 3336 men aged 25‐35 at baseline. 424 classified as at high risk of coronary disease, 868 at low risk. | |

| Interventions | 1. High risk intervention subjects recalled at 6m, 12m, 24m, low risk at 12m, 24m. All intervention subjects measured blood sample, weight, BP, no. of cpd. Given tailored advice on diet, alcohol and smoking at each visit. | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence/reduction at 2 yrs. | |

| Type of intervention | 2. Intensive behavioural: INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING | |

| Notes | This trial was added to the 2005 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 871 male asbestos‐exposed smokers | |

| Interventions | 1.Advice from occupational physician; minimal warning, results of pulmonary function tests, leaflets | |

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 11m | |

| Type of intervention | 2. Intensive behavioural: INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING | |

| Notes | Other outcomes included stratification by lung function, reduction by continuing smokers, predictors of successful quitting and characteristics of smokers refusing to participate in the study. The study found wide variation in implementation of the study procedure by physicians | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

| Methods | Country: Australia | |

| Participants | 431 participants (88%) in 28 stations. av age 32 yrs. 128 smokers, mean cpd 17.9. | |

| Interventions | 1. Health Risk Assessment (HRA): (10 stations, 40 smokers): Measurement of BMI, % body fat, BP, cholesterol, smoking status, aerobic capacity. Feedback given, with high risk people referred to family GP. This minimal 30 minute intervention was the control group. | |

| Outcomes | Baseline, 3, 6 and 12m assessments. | |

| Type of intervention | 2. Intensive behavioural: INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING/ INCENTIVES | |

| Notes | This trial was added to the 2005 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: Japan | |

| Participants | 263 male smokers | |

| Interventions | 1. Physician advice, CO feedback, cessation contract, self‐help materials. follow up over 5m. Smoking Cessation Marathon during month 4 | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence for > 1m at 5m | |

| Type of intervention | 2. Intensive behavioural: INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING | |

| Notes | All male smokers (62.9%) were entered compulsorily into the trial. Female smokers (3.4%) were not included. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Country: France | |

| Participants | 28 site physicians covering 1269 smokers and 2614 nonsmokers | |

| Interventions | 1. Low intensity intervention: Physician advice 5‐10 mins incl. leaflets | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence (self‐reported) for at least 6m at 1 yr follow up | |

| Type of intervention | 2. Intensive behavioural: INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING | |

| Notes | Other outcomes included BMI and depression score | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: Japan | |

| Participants | 228 smokers, randomized to intervention (117) or control (111). Average age 39, av cpd 23; 50% had made previous quit attempts. | |

| Interventions | Baseline questionnaire during routine health check up, with CO and urinary metabolites measured and reported back. | |

| Outcomes | Continuous abstinence at 6m and 12m. Validated by CO ? | |

| Type of intervention | 2. Intensive behavioural: INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING | |

| Notes | This trial was added to the 2005 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: Japan | |

| Participants | Int/Cont: 1382/1736 current smokers, 94%/97.4% M, 92.9%/95.7% blue‐collar workers, 66.1%/61.5% smoke >20 cpd. Significant differences between groups on age, gender, occupation type, cpd, controlled for in analysis. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: 1. Posters, newsletters, website, advertising the cessation campaign and stages of change model. | |

| Outcomes | Sustained 6m abstinence at 12m, 24m, 36m, not biochemically verified. | |

| Type of intervention | 2. INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING/ ENVIRONMENTAL/ INCENTIVES | |

| Notes | New for 2008 update (previously an excluded study) | |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 674 workers (354 intervention and 320 control*) completed baseline survey, and 582 (188 smokers [= current or quit within last 6m]) at 6m follow up. 94% male, mean age 40, smoking prevalence I:45%, C:40%. | |

| Interventions | 3m programme to increase fruit & veg consumption and quit smoking. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported 7‐day PPA at 6m, no verification. | |

| Type of intervention | 2. Intensive behavioural: INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING | |

| Notes | Tools for Health programme; specifically targeted blue‐collar workers. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | 'survey respondents agreeing to participate were randomly assigned to one of two conditions' |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 59 volunteer smokers. Av age 36.8, female 64.5% | |

| Interventions | Self‐help manual; optional education/counselling; financial contracts of US$5 to US$25 bi‐weekly. One group aimed at cessation, the other at reduction or cessation. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported cessation rate immediately post‐treatment and at 6m, biochemically validated at both points (CO, SCN) | |

| Type of intervention | 3. SELF‐HELP | |

| Notes | 15,000 staff members were approached to join the study. Of 137 smokers expressing an interest in the programme, only 59 actually signed up to it. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: UK | |

| Participants | 77 in videotape conditions (33 for smoking video, 44 for seatbelts video), 55 non‐participant smokers (no‐treatment control group). | |

| Interventions | Trial was described to company as a 'health information programme', and was open to all employees, whether or not they smoked. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported PP smoking cessation at 3m and 1yr with CO validation < 10 ppm | |

| Type of intervention | 3. SELF‐HELP | |

| Notes | Although all 4 trials (a‐d) are of similar design, and are reported in a single paper, we have treated them here as four separate RCTs. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: UK | |

| Participants | 150 in videotape conditions (46, 50 and 54 in the 3 groups), + 374 non‐participant smokers | |

| Interventions | Trial was described to company as a 'smoking education programme', and was open only to smokers. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported PP smoking cessation at 3m and 1yr with CO validation < 10 ppm | |

| Type of intervention | 3. SELF‐HELP | |

| Notes | Cash incentives were offered at baseline and at 12m follow up to boost questionnaire response rates. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: UK | |

| Participants | 197 in videotape conditions (56, 67 and 74 in the 3 groups) + 226 non‐participant smokers | |

| Interventions | Trial was described to company as a 'smoking education programme', and was open only to smokers. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported PP smoking cessation at 3m and 1yr with CO validation < 10 ppm | |

| Type of intervention | 3. SELF‐HELP | |

| Notes | Cash incentives were offered at 12m follow up to boost questionnaire response rate. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: UK | |

| Participants | 179 in videotape conditions (62, 59 and 58 in 3 groups) + 360 non‐participant smokers | |

| Interventions | Trial was described to company as a 'smoking education programme', and was open only to smokers. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported PP smoking cessation at 3m and 1yr with CO validation < 10 ppm | |

| Type of intervention | 3. SELF‐HELP | |

| Notes | There were no differences between the video and non‐participants groups in long term abstinence. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 58 smokers | |

| Interventions | 1. American Cancer Society and ALA pamphlets about smoking, a telephone hotline, and a stop‐smoking contest which gave vouchers for a draw, for each day when expired CO < 8ppm. | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 6m | |

| Type of intervention | 3. SELF‐HELP | |

| Notes | Participants in the computer group had lower self efficacy scores than the contest‐only group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 87 smokers | |

| Interventions | 1. The Last Draw, an internet‐based interactive programme to aid preparation, quitting and relapse prevention, plus FadeAid, an aid to nicotine fading | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 6m (7day PP) | |

| Type of intervention | 3. SELF‐HELP | |

| Notes | 73% of Group 1 participants used the interactive programme, compared with 90% of the comparison group who used the ALA programme | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 859 blue‐collar women at baseline (73% of eligible). 538 completed programme to 18m. 53% aged 40 or younger, 58% African American. Mean BMI 29. 30% I group, 22% C group smoked. | |

| Interventions | 1. Intervention: computer‐tailored 'magazine' with dietary, exercise, smoking advice, at baseline and 6m, plus social support at work from trained helpers in participants' chosen activity. N.B. No lay helpers offered smoking support. | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 18m: self‐reported, no biochemical validation. | |

| Type of intervention | 3. SELF‐HELP | |

| Notes | This trial was added to the 2005 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: Belgium | |

| Participants | 199 adult male smokers (av cpd 24‐5) | |

| Interventions | 1. Nicotine gum (4 mg) for at least 3m | |

| Outcomes | PP abstinence at 12m | |

| Type of intervention | 4. PHARMACOLOGICAL | |

| Notes | Blinding was broken at 3m, and participants were free to choose their dosage of nicotine gum. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

| Methods | Country: UK | |

| Participants | 270 participants invited out of 334 who expressed an interest | |

| Interventions | 1. Nicotine gum (2 mg) at least 4 boxes, duration not stated. (172 people) | |

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 12m; Validation: expired CO | |

| Type of intervention | 4. PHARMACOLOGICAL | |

| Notes | Slight contamination of intervention group, as 4 control group members were moved at their own request into the intervention group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

| Methods | Country: UK | |

| Participants | 161 adult smokers who were still smoking after 3m of a videotape smoking cessation programme. Av cpd 15‐19 | |

| Interventions | 1.Nicotine gum (2 mg) for up to 12w | |

| Outcomes | Validated long‐term abstinence at 12m | |

| Type of intervention | 4. PHARMACOLOGICAL | |

| Notes | Participants are the non‐quitters at 3m from Sutton 1988d | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

| Methods | Country: Belgium | |

| Participants | 374 volunteers | |

| Interventions | 1.Active patch and active gum (2mg as required) | |

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 12m | |

| Type of intervention | 4. PHARMACOLOGICAL | |

| Notes | Other outcomes included dermatological and systemic adverse effects, and time to relapse. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Country: Spain | |

| Participants | 218 participants randomized to intervention (115) and control (103). All had physical check up, Fagerstrom NTQ, lab tests and ECG at baseline | |

| Interventions | 1. Intervention: 5‐8 mins structured individual counselling on smoking cessation at baseline by occupational physician, + further contacts at 2 days, 15 days and 3m. Grade I (Fagerstrom score < 5) counselling only. Grade II (Fagerstrom score 5‐7) 8 wks x14 mg nicotine patches. Grade III (Fagerstrom score > 7) 4 wks x 21 mg, 4wks x 14mg, 4wks x 7mg. Lower grade interventions could be upgraded if necessary. Participants kept records of progress, withdrawal symptoms, adverse events; weight and tobacco consumption were checked at specified intervals. | |

| Outcomes | Continuous abstinence (7 day PP at each assessment) at 12m. | |

| Type of intervention | 4. PHARMACOLOGICAL | |

| Notes | This trial was added to the 2005 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 24 participants av age 34, had smoked for an average of 16 years, and av cpd 24. | |

| Interventions | Group therapy | |

| Outcomes | Self‐monitoring records, laboratory analyses of spent cigarette butts, and CO at 6m | |

| Type of intervention | 5. SOCIAL SUPPORT | |

| Notes | Other outcomes included nicotine levels (brand smoked), smoking reduction, CO levels in continuing smokers and % of cigarette smoked. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country:USA | |

| Participants | 29 adult cigarette smokers | |

| Interventions | 1. Basic program (BP): subjects participated in 6 weekly group meetings‐ focused on making reductions in the no. of cpd and reductions in nicotine content. Midway through the programme subjects given the option of either complete cessation or reducing the percentage of each cigarette smoked. | |

| Outcomes | Self reports, examination and weighing of saved cigarette. Butts and 2 biochemical measures of smoking exposure, CO and saliva thiocyanate. | |

| Type of intervention | 5. SOCIAL SUPPORT | |

| Notes | Outcomes included changes in nicotine content (brand smoked), amount of cigarette smoked, and number of cigarettes smoked. The influence of social support, or lack of it, was also assessed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 30 smokers (14 at intervention site and 16 at comparison site) | |

| Interventions | 1. Intervention: comprehensive programme of smoking control, discouragement, cinnamon sticks as cigarette substitutes, and smoking cessation | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported smoking cessation with urinary cotinine validation | |

| Type of intervention | 6. ENVIRONMENTAL SUPPORT | |

| Notes | Introduction includes lengthy discussion of economic and health costs of smoking | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | Random sample of 400‐500 employees screened at baseline and followed up 3 yrs later. | |

| Interventions | Smoking, high blood pressure & obesity targetted. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported smoking status | |

| Type of intervention | 6. ENVIRONMENTAL SUPPORT | |

| Notes | Quit rates were calculated by combining 1985 smokers and ex‐smokers (i.e. at risk of relapse)as the denominator. If the calculation is based only on current smokers at 1985 compared with 1988 quitters, the results do not reach statistical significance. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 6 worksites ranging in size from 950 to 3,300 employees. 25% smoking prevalence. | |

| Interventions | 1. Full programme (I): volunteers participated in a 5w training programme for quit‐smoking group leaders, and received additional training ,support, and how‐to manuals to carry out a protocol for health education and sitewide intervention activities, as well as for the implementation of worksite smoking policies. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported cessation at 12m | |

| Type of intervention | 6. ENVIRONMENTAL SUPPORT | |

| Notes | Unit of randomization was worksite but unit of analysis was the individual. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 47 subjects who completed 5 days verified abstinence. | |

| Interventions | 1.Contingent payment for continued abstinence + frequent monitoring (n = 17) | |

| Outcomes | Quit rate at 6m, confirmed by CO validation | |

| Type of intervention | 7. INCENTIVES | |

| Notes | Subjects had received a minimal cessation programme, i.e. a 15‐minute talk and a booklet, with no skills training in cessation or relapse prevention. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 378 smokers | |

| Interventions | All groups received a 10 minute session of brief advice | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 1 yr (sustained at 6w, 6m & 1 yr) | |

| Type of intervention | 6. ENVIRONMENTAL SUPPORT/ INCENTIVES | |

| Notes | Other outcomes included some cost‐benefit analysis, including efficacy of incentives.. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | Worksites from 140‐600 employees. Smoking prevalence of 21‐22%; Av age 40‐41. 63% female. 474 in Incentives (I) Group, 623 in No incentives (NI) Group | |

| Interventions | Company steering groups ran the programmes | |

| Outcomes | Cessation rates at 12m and 2 yrs, verified by CO and salivary cotinine | |

| Type of intervention | 7. INCENTIVES | |

| Notes | Analysis was at both worksite and individual level. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 2402 smokers on 24 sites, four sites randomized to each of the 6 conditions. There were significant differences in demographic characteristics between sites. | |

| Interventions | The three programme formats were group counselling, telephone counselling or a choice of group or phone. | |

| Outcomes | Rates of recruitment to the programmes, and 7‐day smoking PP at 12m and 24m follow up. | |

| Type of intervention | 7. INCENTIVES | |

| Notes | This is the SUCCESS Project. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country:USA | |

| Participants | 2887 workers across 9 sites at baseline HRA survey (69% of eligibles). At 2 yr follow up 1998 (48%) were surveyed. Cross‐sectional, not cohort surveys. | |

| Interventions | 1. (3 sites, 1372 participants): HRA (height, weight, smoking, BP, cholesterol, HDL levels) at start and end of programme, + a bi‐monthly health newsletter (counts as control group). | |

| Outcomes | Smoking prevalence at 2 yr follow up in all four intervention groups. Self‐report 'current smoker' at HRA; no biochemical confirmation. | |

| Type of intervention | 8. COMPREHENSIVE | |

| Notes | This trial was added to the 2005 update. | |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 26 heterogeneous worksites in Oregon with between 125 and 750 employees ‐ an average of 247. | |

| Interventions | Take Heart Project, focusing on diet and smoking | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported smoking cessation | |

| Type of intervention | 8. COMPREHENSIVE | |

| Notes | This is the Take Heart worksite wellness program. Other outcomes included dietary intake and cholesterol levels | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 108 worksites with over 28,000 employees ( 49 ‐ 1700 workers per site). Participation rate 72%, Av age 41, 77% male, 92% white. | |

| Interventions | Each workplace had an employee as co‐ordinator, and an employee advisory board. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported smoking cessation, without biochemical validation. 6m abstinence at follow up, smoking prevalence. | |

| Type of intervention | 8. COMPREHENSIVE | |

| Notes | This is the Working Well Trial. The Working Well trial generated a nested cohort study, the WellWorks Trial, which examined dietary and smoking changes stratified by job type at the Massachusets worksites. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 5914 (61%) of sampled employees responded at baseline, and 5406 (62%) at 2 yr follow up. | |

| Interventions | 3 elements of intervention: | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported abstinence for 6m before final survey. | |

| Type of intervention | 8. COMPREHENSIVE | |

| Notes | The WellWorks Study is a nested component of the Working Well trial, but, unlike that trial, attempted to integrate health promotion and health protection interventions, and is therefore assessed separately. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: Holland | |

| Participants | 279 employees at intervention sites and 234 employees at comparison sites | |

| Interventions | 1. Comprehensive program (self‐help manuals, group courses, a mass media campaign, smoking policies and a 2nd yr programme) | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported smoking cessation and saliva cotinine estimation | |

| Type of intervention | 8. COMPREHENSIVE | |

| Notes | Analysis of light vs heavy smokers suggests greater efficacy among heavy smokers (P values not given). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 22 worksites, and 2055 participants who completed all surveys. No demographic differences between intervention and control groups. Smoking prevalence 28% across both groups. | |

| Interventions | 1. Intervention sites: As with Working Well Trial (Sorensen 1996), but including physical activity; a combination of individual and environmental programmes, including space, showers, equipment and discounted membership of fitness facilities. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported abstinence at 3 yrs for 6m prior to assessment, and 7‐day PP | |

| Type of intervention | 8. COMPREHENSIVE | |

| Notes | This trial was added to the 2005 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: Sweden | |

| Participants | Of 128 at‐risk workers invited, 60/65 randomized to the intervention group attended for baseline assessment, and 53/63 from the control group. | |

| Interventions | 1. Intervention group received 16 group sessions a year, as well as individual counselling by a nurse. Sessions included lectures, discussions, video sessions and outdoor activities. | |

| Outcomes | PP at 12m and 18m. No biochemical validation. | |

| Type of intervention | 8. COMPREHENSIVE | |

| Notes | Smoking was only one of several risk factors targeted, including BMI, BP,heart rate, low‐density lipoprotein and cholesterol. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Country: USA | |

| Participants | 9019 employees (80%) across 15 sites. Mean workforce size 741 employees. Responders in the control groups were younger, more likely to be female, less educated, less likely to be white, and less likely to be hourly‐paid rather than salaried. | |

| Interventions | 1. Control [8 sites] had Health Promotion (HP) intervention, i.e. consultation to management on tobacco control policies, catering and cafeteria policies, and programmes aimed at individuals, including self assessment with feedback, self‐help activities, contests, demonstrations and displays, opportunities to try behaviours and goals, and group discussions. | |

| Outcomes | Quit rates (PP) at 6m, reported by cross‐sectional survey and for the smoking cohort. | |

| Type of intervention | 8. COMPREHENSIVE | |

| Notes | This is the Wellworks‐2 Trial, targeting particularly blue collar workers. Analyses were cross‐sectional and cohort | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

ALA: American Lung Association

av: average

BMI: body mass index

BP: blood pressure

CO: carbon monoxide

cpd: cigarettes per day

ETS: environmental tobacco smoke

FTND: Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence

h: hour

HDL: high density lipids

HRA: health risk assessment

inc: Including

I: intervention; C: control

m: month

NRT: nicotine replacement therapy

NTQ: nicotine tolerance questionnaire

PPA: point prevalence abstinence

ppm: parts per million

RCT: randomized controlled trial

S‐H: self help

vs: versus

w: week

yr: year (s)

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Observational study, no control worksites. Smoking was one of a number of lifestyle changes surveyed over a three‐year period, by a follow‐up postal survey six months after assessment. | |

| RCT for smoking reduction; 2m duration | |

| Follow‐up only four months. Evaluated the impact of a hospital smoking ban with no report of cessation programmes. | |

| Pre/post study, no control group, assessment at 5m | |

| Non randomized. Evaluated the relative efficacy and cost‐effectiveness of a stop smoking clinic versus self‐help kit in the workplace | |

| Examined predictors of smoking cessation attempts not cessation rates after the introduction of workplace smoking bans. | |

| One group post‐test only. Surveyed smokers two years after a total workplace ban. | |

| Population‐based survey, to assess the effects of workplace smoking bans and cessation rates, expressed as a quit ratio | |

| One group, post‐test only. Evaluated smoking regulations at the workplace and smoking behaviour in Southern Germany. | |

| Follow‐up for only four weeks. Examined the effects of a restricted worksite smoking ploidy on employees who smoke. | |

| Pre‐ and post‐ban surveys on three buildings (137 workers), to assess air quality and physical symptoms of ETS. Prevalence was not a primary outcome, but was reported as unchanged between the two surveys | |

| Description of a cardiovascular risk reduction intervention in a power plant; no control or comparison site | |

| Descriptive report of a computer‐directed programme for smoking cessation treatment. Previous reported outcome data from a minimal intervention and intensive stop smoking treatment are presented. | |

| Observational study of 2 German factory interventions. | |

| Cross‐sectional survey of 859 women in nine North Carolina worksites, to assess health behaviours, risks and desire to change behaviour. A population‐based survey, with no control group or intervention. | |

| 6 wk RCT of patches for reducing craving. | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluated exposure to a worksite health‐promoting environment as an aid to smoking cessation. | |

| Eight years had lapsed between surveys. Evaluated the impact of a smoking ban in a large Paris hospital | |

| Large cohort study, not a controlled intervention trial | |

| One group, no pre‐test . Evaluated the effect of a smoking ban with partially subsidised cessation programmes. | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluation of a smoking cessation treatment programme of ten one‐hour sessions. | |

| Follow‐up for only four months. A programme of smoking control in one company versus a smoking cessation class in a second company. | |

| Outcome not smoking cessation but bartenders' respiratory health. Evaluated the respiratory health of bartenders before and after legislative prohibition of smoking in all bars and taverns by the state of California. | |

| Outcome not smoking cessation. Evaluated the effectiveness of incentives as an aid to recruitment. | |

| Survey of Norwegian nurses' smoking | |

| Follow‐up for only four months. Evaluated a short‐term impact of a University‐based smoke‐free campaign. | |

| Non‐workplace for part of study. Evaluated the association of household and workplace smoking restrictions with quit attempts, six month cessation and light smoking. | |

| Cross‐sectional not pre‐post‐test. Estimated the impact of workplace smoking restrictions on the prevalence and intensity of smoking among all indoor workers. | |

| Comparison of of CHD risk factor interventions and musculo‐skeletal interventions in Welsh workplaces. Outcome was acceptability and feasibility in small workplace. | |

| Data from a population‐based survey of adult smokers who completed surveys in 1988 and 1993, as part of the COMMIT trial. | |

| Follow‐up for only six weeks. Examined the short‐term effects of a workplace smoking ban on indices of smoking, cigarette craving, stress and other health behaviours in 24 employees. | |

| Non‐randomized. Three‐stage study included a baseline survey, an assessment of the effects of competition on recruitment to a self‐help cessation programme and examination of the outcome of the cessation programme. | |

| Observational study, no control group | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluation of a self‐help smoking cessation programme for registered nurses. | |

| Assessment of counsellors' skills and success rates in 6 Japanese worksites. | |

| Evaluation, no control group. | |

| Follow‐up for only three weeks. Examined the effects of acupuncture on smoking cessation or reduction for motivated smokers. | |

| Nine Finnish worksites surveyed before and after legislation to restrict ETS; not a controlled trial | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluated the effectiveness of a worksite smoking cessation programme in the military. | |

| Non‐randomized study, with no control or comparison group, and short follow‐up (timing not stated). Surveyed five workplaces before and after a one‐year health promotion campaign, targeting multiple health behaviours, including smoking. Primarily interested in gender and social class differences | |

| Evaluation study, no control group | |

| Outcome was daily cigarette consumption, cessation rate not reported. Study was designed to assess changes in employee health, particularly weight gain and CO levels, and smoking behaviour. | |

| Community‐based, not workplace. Evaluated the effects of postal smoking cessation advice in smokers with asbestos exposure and /or reduced forced expiratory volume in one second. | |

| The SMART study; RCT, targeting employed adolescents rather than adults. | |

| Healthy Directions ‐ Small Businesses study; RCT, but smoking cessation was not the target intervention, and was offered in both intervention and control sites (=24). | |

| Evaluation of Allen Carr programme; no control group | |

| Non‐randomized. Examined the factors critical to behaviour modification with respect to smoking cessation at worksites. | |

| Non randomized. A cessation programme with incentives and competition offered in one company, compared to a control company. | |

| Ten‐year Japanese programme of annual small‐scale smoking cessation interventions; assessed at two months, but primary outcome was overall prevalence after ten years. Controlled trial, but not randomized. | |

| Population‐based telephone survey of 1228 employed adults to assess impact of worksite smoking policies. | |

| Non‐randomized. A smoking cessation programme offered in five companies, with and without competitions for participation and cessation. | |

| Not a randomized study, as one of the three participating worksites refused to be randomized. | |

| Survey of post‐intervention multiple lifestyle changes, including number of cigarettes smoked. No control group used. | |

| Not pre‐post‐test evaluation but post‐ban quit ratio. Examined the impact of workplace smoking bans on smoking behaviour of employees. | |

| Not pre‐post‐test. Examined the long term impact of workplace smoking bans on employee smoking cessation and relapse. | |

| Cessation was not an outcome of interest. Evaluated method of contact (phone vs letter) as an aid to recruitment. | |

| Non‐randomized. Two worksites offered a multi‐component behavioural programme with nicotine gum. Additional competition in one site. | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluated the effectiveness of a multi‐component smoking cessation programme supplemented by incentives and team competitions. | |

| Small non‐randomized pilot study, based on stages of change model, to compare expert systems, group support and self‐help manuals. | |

| Happy Heart at Work programme; 10‐yr evaluation, without a control group | |

| Survey of changes in risks among GM employees; not a controlled trial | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluated the effectiveness of a smoking cessation programme known as 'Smoke Busters'. | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluation of a minimal contact smoking cessation programme at the worksite. | |

| Evaluation of an anti‐smoking programme, without a comparison worksite | |

| Evaluation study, no control group | |

| Evaluation study, no control group | |

| One group, post‐test only. Evaluated the effect of a smoking ban, with no‐cost nicotine dependence treatment. | |

| One hospital had pre‐test data. Evaluated changes in employee smoking behaviour after implementation of restrictive smoking policies. | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluation of a smoking cessation incentive programme for Dow chemical employees in the USA. | |

| Non‐randomized. A five‐year evaluation of a smoking cessation incentive programme for chemical employees. | |

| Cost‐effectiveness rather than efficacy evaluation. | |

| Population‐based telephone survey of 1844 Californian adult indoor workers, to assess changes in smoking status and cigarette consumption, related to whether or not their workplace was smoke‐free, and for how long the ban had been in place.. | |

| The Heart At Work programme. Smoking prevalence was measured, but was not an intervention outcome | |

| Cohort study, no comparison worksite | |

| Non‐workplace setting. A smoking cessation programme for use in general practice | |

| Post‐test only. Evaluated a non‐smoking policy in a health maintenance organization | |

| Non‐workplace setting for half of the participants. Evaluated nicotine gum and advice versus advice only for smoking cessation. | |

| 594 employees at a UK pharmaceutical company (GSK) attempted to quit with bupropion, and were followed up at six months. Not an RCT. | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluation of 'BUTT OUT' , a quit smoking programme developed specifically for the Canadian Armed Forces. | |

| Non‐randomized. Nurses in different units offered cessation treatment or a waiting list control. 29 participants. | |

| Non‐randomized. Determined the effect of a smoking cessation programme compared with health screening on employee smoking. | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluated cessation and relapse in a year‐long workplace quit‐smoking contest. | |

| One group post‐test only . Evaluated the impact of a restrictive smoking policy with free onsite smoking cessation classes. | |

| RCT of teenagers (aged 15‐17) working part‐time, many still in school. | |

| Evaluation of a Swedish hospital smoking ban, but without a comparison worksite | |

| Non‐randomized. Smoking intervention based on risk communication in subjects at risk of asbestos‐related lung cancer. | |

| Did not report smoking cessation rate. Compared the reported prevalence and acceptance of bans on smoking among indoor workers in South Australia. | |

| One group, post‐test only. Determined the impact of a smoking cessation programme using nicotine replacement therapy as part of a larger wellness programme. | |

| Comprehensive health promotion intervention, but not a randomized trial | |

| Non‐randomized. Evaluated a smoking cessation intervention for Dutch employees consisting of self‐help methods and a group programme. | |

| Non‐randomized. Examined the impact of a comprehensive worksite smoking cessation programme on employees who do not take part in cessation activities. | |

| Results of the 1990 California Tobacco Survey; 11704 working adults responded. Aim was to assess relationship of worksite policy (or its absence) to smoking status, controlling for demographic factors |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Australian National Workplace Health Project |

| Methods | Cluster‐randomized trial, 20 worksites, 2x2 factorial design |

| Participants | Employees in participating worksites. 2498 completed baseline survey, 2082 completed health risk appraisal |

| Interventions | Socio‐behavioural and environmental intervention, for physical activity, healthy eating, smoking and alcohol |

| Outcomes | Behaviour change at 1 and 2 yrs |

| Starting date | NK |

| Contact information | |

| Notes | Included in 2005 update; no further info for 2008 update |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 Results of included studies Show forest plot | Other data | No numeric data | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Analysis 1.1

Comparison 1 Results of included studies, Outcome 1 Results of included studies. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Any behavioural therapy (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 1 Any behavioural therapy (various endpoints). | ||||

| 2 Individual Counselling (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.2  Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 2 Individual Counselling (various endpoints). | ||||

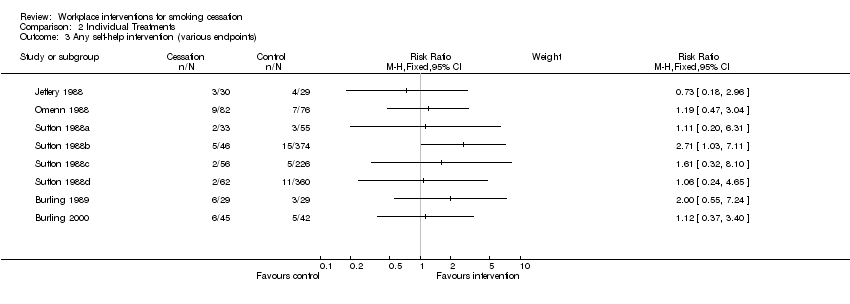

| 3 Any self‐help intervention (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.3  Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 3 Any self‐help intervention (various endpoints). | ||||

| 4 Pharmacological Treatments (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.4  Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 4 Pharmacological Treatments (various endpoints). | ||||

| 5 Social support Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.5  Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 5 Social support. | ||||

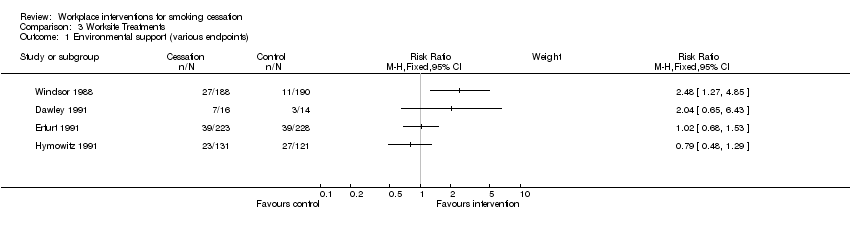

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Environmental support (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 3.1  Comparison 3 Worksite Treatments, Outcome 1 Environmental support (various endpoints). | ||||

| 2 Incentives (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 3.2  Comparison 3 Worksite Treatments, Outcome 2 Incentives (various endpoints). | ||||

| Study | Baseline/follow‐up | Smoking outcome | Validated ? |

| Burling 1989 | 58 smokers, all given self‐help materials and support. Experimental group (29) also exposed to computerised nicotine fading. | No significant difference in quit rates. 3/29 in Group 1 vs 6/29 in Group 2. | Validation (participation and abstinence) measured at CO>8ppm |

| Burling 2000 | 87 smokers, randomised to an interactive nicotine fading programme, or a conventional cessation programme. | No significant difference in quit rates. 6/45 in Group 1.vs 5/42 in Group 2. There was more evidence of effect for those who used the programmes than for those that didn't. | |

| Cambien 1981 | 304 intervention smokers recalled at 2 yrs, and 306 control smokers. 195 participants lost to follow up, proportion of smokers not reported | 21.4% of intervention smokers quit, vs 13.4% of control smokers. Point prevalence at 2 yrs, not a significant difference | Validation by blood CO levels |

| Campbell 2002 | 538 women in 9 worksites (4 exp, 5 control) completed all surveys (282 I, 256 C) to 18m. | No raw data given for smoking, but prevalence went down by around 3% in both groups. No significant differences, and no p values. | Self‐report on all outcomes, no biochemical validation |

| Dawley 1991 | 16 employees in the experimental company (comprehensive programme), and 14 in the comparison company (cessation‐only programme) | Comprehensive Group achieved 43% (7/16) quit rate at 5 months, while the Cessation‐only Group achieved 21% (3/14). P‐values not given, but numbers too small for significant difference. | Validation by urinary cotinine |

| DePaul 1987 | 425 smokers in 43 corporations, randomised to group support programmes or self‐help alone programmes | 6% vs 2% continuously abstinent (NS), 19% in both groups were abstinent at 12 months point prevalence. | Partial validation by salivary cotinine, with family and colleague report |

| DePaul 1989 | 419 smokers in 38 worksites, randomised to experimental programme (206) and comparison programme (213). The attrition rate was 17% for Group worksites and 29% for Non Group worksite participants, so correcting the data for attrition would increase the apparent efficacy of the Group condition. | At the company level of analysis the 12 month point prevalence quit rates were Group 26% vs No Group 16% (p<0.06); continuous abstinence rates were 11% (Group) vs 3% (No Group) (p<0.05). | Partial validation by salivary cotinine, with family and colleague report |

| DePaul 1994 | 844 smokers in 61 worksites, randomised to Self‐help [SH] (289), Incentives [I] (281) or Group support [G] (283). | 12 month quit rates for sustained abstinence were 5.1% (n=79) SH, 11% (n=91) I, 31.2% (n=109) G (p<0.01). An Intention to Treat analysis, taking account of attrition, would further favour the intervention groups. | Validation by salivary cotinine at 6 months, and CO<9ppm at 12 months |

| Emmons 1999 | 2055 workers (28% smokers) completed all surveys from 22 worksites, and constituted the cohort. | At 3 yr final follow up, 8.0% of the intervention smokers had quit for 6m, and 8.1% of the control smokers. 25.6% and 21.8% respectively claimed 7‐day PP. Differences were non‐significant | Self‐report, with no biochemical validation |

| Erfurt 1991 | Four sites were assessed at baseline; Site 1 had 1096 smokers (45%), Site 2 598 (44%), Site 3 844 (41%) and Site 4 834 (44%). | Participation was affected by the intervention: 5% in Site 1, 9% in Site 2, 53% in Site 3 and 58% in Site 4. | Self‐report only, not biochemically validated |

| Frank 1986 | 48 smokers initially randomised to three groups, with varying levels of hypnosis, booster and self‐management training. A 4th group (15 smokers) was later recruited, with Group 2 interventions applied more intensively. | No difference between the groups for smoking cessation 6 months after treatment, regardless of the frequency, length between sessions, or addition of behavioural methods. Quit rate was 20% for all groups, based on Intention to Treat. | Salivary cotinine measured at 3 months, but self‐report only at 6 months |

| Glasgow 1984 | 36 employees, randomised to abrupt reduction (13), gradual reduction (12) and gradual reduction + feedback (11). | At 6 months up to one third in the gradual condition were abstinent compared to no subjects in the abrupt condition (NS). | CO<10 ppm at 6 months, weighing of cigarette butts |

| Glasgow 1986 | 29 employees randomised to Basic Programme (13) or Basic Programme + Social Support (16). | Consistent with previous findings, supportive social interactions were not related to treatment outcome.3/13 in the Basic Programme had quit at 6 months, and 3/16 in the Basic + Social Support Group (NS). | Self report, weighing of cigarette butts, CO monitoring and salivary thiocyanate |

| Glasgow 1993 | 19 worksites, random allocation to Incentive programme (474 smokers) or No Incentive programme (623 smokers). | At 2 year follow‐up 49/344 (14%) were abstinent in the Incentives group, and 49/426 (12%) in the No incentives group (NS). Intention to Treat analysis would give more conservative quit rates | CO monitoring and salivary cotinine |

| Glasgow 1995 | 26 worksites, randomised to early or delayed interventions. 1222 employees were followed up at 2 years. | Comprehensive programme; a 26% rate of cessation was noted across both longitudinal cohort groups (NS), and a 30% rate across both cross‐sectional groups (NS). No significant differences were seen between the 2 types of intervention | Self report, not biochemically validated |

| Gomel 1993a | 28 ambulance stations randomized to 4 levels of risk reduction intervention. 128 baseline smokers followed for 1 yr | No significant differences between HRA and RFE groups at any follow‐up point, nor between BC and BCI groups. HRA and RFE groups (68 smokers) were pooled and compared with 60 smokers in pooled BC and BCI groups. Continuous abstinence rates at 6m were 1% for HRA+RFE and 10% for BC+BCI (Fisher's Exact Test p=0.05); 12m rates were 0% and 7% (p=0.05). | Serum cotinine validation used. |

| Gunes 2007 | 200 smokers randomized to 7‐step behavioural programme or no intervention, followed for 6m | ||

| Hennrikus 2002 | 24 worksites, randomised to 6 programmes, 4 worksites in each programme. 2402 smokers were surveyed at baseline and at 12 and 24 months. 85.5% response rate at 12 months, and 81.7% at 24. | 407 (17%) smokers signed up to programmes. 15.4% at 12 months and 19.4% at 24 months reported themselves as non‐smokers. | Self‐report, validated by family member or friend. |

| Hymowitz 1991 | Six worksites randomised to Full Programme or Group‐only interventions. Participation was 50% in the Full Programme sites, and 44% at Group‐only (NS). | At 12 months, 23/131 (18%) in the Full Programme arm had quit, while 27/121 (22%) in the Group‐only arm had quit (NS). | Self‐report and expired CO<8 ppm. |

| Jeffery 1988 | 59 employees were randomly assigned to reduction (29) or cessation (30) groups, and surveyed at baseline and at 6 and 12 months. Attrition was 30% ‐ intention to treat analysis. | At 12 months 4/29 (14%) had quit in the reduction group, and 3/30 (10%) in the cessation group. No significant differences between the groups on either of the outcomes (dropout rate, cessation at 12 months). | self‐report confirmed by expired CO<8 ppm. |

| Kadowaki 2000 | 263 male employees randomised to intervention (132) or control (131). | Quit rates 17/132 (Intervention), 4/131 (Control) at 5‐month follow‐up (p=0.003). Male smoking decreased from 62.9% to 56.7% (p=0.04). | Expired CO<9 ppm at baseline, 5 months and 12 months, and a urine test at 12 months |

| Klesges 1987 | 136/480 smokers over 8 worksites; all received a behavioural programme, with the intervention sites also receiving a competition and prize component. Each group of sites (Intervention and Control) were also divided between relapse prevention training (2) and no relapse training (2). | Competition intervention resulted in significantly higher quit rates at the end of the trial (39% vs 16%, p<0.004) but these differences decayed at 6 months (12% vs. 11%, NS ). | Expired CO<10 ppm |

| Kornitzer 1980 | 30 Belgian factories (16,230 men) randomized to intervention (risk assessment, physician and written advice) or control (assessment only). tested at 2 yrs. | High risk intervention group (n=1268) reduced prevalence by 18.7% (84.5% to 68.7%), and high risk control group (n=202) reduced by 12.2% (80.8% to 70.9%). P < 0.05. | Self report only, no biochemical validation. |

| Kornitzer 1987 | 199 employees were randomised to receive 2mg (101) or 4mg (98) nicotine gum. | At 3 months 36% of the 2mg group and 45% of the 4mg group claimed to be abstinent. At that point,blinding was broken and individuals could choose their treatment group. Results were stratified by Fagerstrom score dependency. At 12 months, the 4mg group (90) had a 50% higher abstinence rate than the 2mg group (94) (p<0.05); this fails to reach significance if an intention‐to‐treat analysis is conducted. In the first 3 (blinded) months of trial, the heavier smokers benefited more from the higher dose gum. | Baseline and 12 month cotinine blood samples (random sample of 69% at 12 months). |

| Kornitzer 1995 | 374 employees randomised to Group 1(149, active patch + active gum), Group 2(150, active patch + placebo gum) or Group 3(75, placebo patch + placebo gum) | At 12 months, abstinence in Group 1 was 18.1% (NS), in Group 2 12.7% (NS) and in Group 3 13.3% (NS). Time to relapse was significantly longer in Group 1 compared with the other 2 groups (p=0.04). | Salivary cotinine at baseline, and expired CO<10 ppm at subsequent checks |

| Lang 2000 | 30 worksite physicians (1095 smokers) were randomised to Group A (504, simple advice) or Group B (591, advice + support and 'contract'). | 2 physicians dropped out post randomisation. | Self‐report, with CO<7 ppm validation on a subset of 231 subjects whose physicians had access to a CO monitor. |

| Li 1984 | 871 employee smokers, randomised to Group 1 (simple warning) or Group 2(brief physician advice), stratified by normal/abnormal lung function. | Counselled workers had an 8.4% abstinence rate at 11 months, compared with 3.6% in the control group (p<0.05). | Expired CO<10 ppm at 11 months follow‐up in all quitters, and in a random sample of 379 continuing smokers |

| Malott 1984 | 24 employees randomised to controlled smoking Group (1) or controlled smoking + partner support Group (2). | Few differences were observed between controlled smoking and controlled smoking plus partner support conditions either during treatment or at the 6‐month follow‐up. 25% of Group 1, and 17% of Group 2 were abstinent at 6 months (NS). | Self‐monitoring, butt counts, expired CO levels |

| Nilsson 2001 | 113 workers randomised to intervention (65) or control (63). | Baseline prevalence for both groups was 65%. At 12 months the intervention group point prevalence rate was 37%, and the control group 63%. At 18 months, the rates were 40% and 59% respectively. This difference influenced the decrease in mean risk score from 10.3 to 9.0 after 18 months in the intervention group (p=0.042) | Self‐report, not biochemically validated |

| Omenn 1988 | 402 employee smokers randomised within their preference for group or self‐help programmes, to 3 programmes, MCP (1), RPP (2) or MTP (3). | Self‐reported quit rates similar across all three group preference conditions but more missing saliva samples in self‐help so validated rates lower. | Salivary cotinine at 12 months <35 ng/ml |

| Rand 1989 | 47 employees randomised to contingent payment/frequent CO monitoring group (17), non‐contingent payment/frequent CO monitoring (16), non‐contingent payment/ infrequent monitoring (14). | Contingent payment combined with frequent CO monitoring delayed but did not ultimately prevent participant relapse to smoking by the end of the six month follow‐up. Contingent payment group had CO value at or less than 11 ppm significantly longer than the other two groups (p=0.03). CO monitoring alone had no effect on abstinence. | Expired CO monitoring <12 ppm |

| Razavi 1999 | 344 post‐cessation abstainers randomised to psychologist support (135), ex‐smoker support (88), or no formal support (121), | 12 months abstinence rates were 59/135 (43.7%) in the PG group; 33/88 (37.5%) in the SG group; 43/121 (35.5%) in no support group (NS). | Expired CO and urinary cotinine. Unvalidated self‐report (higher) were also given. |

| Rodriguez 2003 | 218 smokers randomized to counselling + NRT (115) or minimal sporadic advice (103) in 3 Bilabao (Spain) worksites | 12 months continuous abstinence rates were 23/114 (20.2%) for the intervention group, vs 9/103 (8.7%) in the control group (P = 0.025). | Expired CO <+ 10 ppm |

| Schröter 2006 | 38 smokers assigned to standard behavioural (SB) programme, 41 to relapse prevention (RP) programme. | 12m continuous abstinence rates were 8/38 (21.1%) for SB, and 5/41 (12.2%) for RP. | Self‐reported, no biochemical validation |

| Shi 1992 | 2887 workers (533 smokers) across 9 Californian sites, partially randomized to 4 intervention levels. No non‐intervention control group | 2 yr cross‐sectional survey of 1998 workers (250 smokers); Prevalence declined by 34% from 18% to 12% in Level 1 (p < 0.1); by 18% from 17% to 14% in Level 2 (p < 0.1); by 35% from 24% to 15% in level 3 (p < 0.01); by 44% from 14% to 8% in Level 4 (p < 0.01) | Self‐reported PP at HRA, not biochemically validated |

| Shimizu 1999 | 53 volunteer employee smokers, randomised to intervention and control groups. | After the 5 months of intervention, smoking cessation rate in the intervention group (19.2%) tended to be higher than that in the control group (7.4%), (NS). | Expired CO monitoring |

| Sorensen 1993 | Eight worksites, randomised to intervention (1885 workers) or comparison (1479 workers). | Analysis of all smokers, not just participants. | Self‐report only. |

| Sorensen 1996 | 108 matched worksites (>28,000 workers), randomised to intervention or control conditions, though Florida center sites did not target smoking, leaving smoking outcomes available in only 84 worksites. | Worksite was the unit of allocation and analysis. Baseline smoking data were not reported in detail. | Self‐reported, no biochemical validation |

| Sorensen 1998 | Cohort analysis (2658 employees) of a randomised controlled study of 12 matched pairs of worksites. | PP abstinence for the 6 months prior to 2‐year follow‐up was 15% for intervention group and 9% for control group (p=0.123) | Self‐reported, no biochemical validation |

| Sorensen 2002 | Cross‐sectional analysis (9019 at baseline [80%] and 7327 [65%] ) at six months follow‐up, plus cohort analysis of 5156 employees who responded to both surveys (embedded cohort of 436 smokers). | At six months, point prevalence in the HP/OHS sites fell from 20.4% to 16.3%, and in the HP sites from 18.6% to 17%. | Self‐reported, no biochemical validation |

| Sorensen 2007 | Baseline participants 674 workers, (354 Int/ 320 Cont). | 7‐day self‐reported PPA at 6m: Int: 19/101 (19%), Cont: 7/87 (8%) (P=0.03). | Self‐reported, no biochemical validation |

| Sutton 1987 | 270/334 interested smokers invited to nicotine gum cessation programme; the uninvited 64 represented a control group. 172 (64%) of invitees attended the 1st consultation, 163 the 2nd. | 12% (20/172) of those who attended the intervention course were abstinent at 12 months, compared with 1% (1/98) of those who did not accept the invitation, and 2% (1/64) of the control group; p values not given. | Expired CO<11 ppm |

| Sutton 1988a | Video programme (smoking, plus seat‐belt advice) was offered to all employees. 77 employees were randomised to DFF video (33) or seatbelt (44=control) videos. | Abstinence rates (DFF: 3%, SB [control] 0%) were not significantly different from each other at 12 months follow‐up, There was no significant difference in validated abstinence between the video groups and the non‐participant group. | Expired CO<11 ppm. |

| Sutton 1988b | 150 employees (smokers only) participated. 46 watched the DFF video, 50 watched a confidence‐boosting version of the DFF video, and 54 (control group) watched LTK video. | Abstinence rates (DFF: 11%, DFF+C 8%, LTK [control] 9%) were higher than in the other 3 studies, but not significantly different from each other | Expired CO<11 ppm. |

| Sutton 1988c | 197 employees (smokers only) participated. 56 watched the DFF video, 67 watched a less gory version of the DFF video, and 74 (control group) watched the TW video. | Abstinence rates (DFF: 4%, DFF‐G 3%, TW [control] 4%) were not significantly different from each other. | Expired CO<11 ppm. |

| Sutton 1988d | 179 employees (smokers only) participated. 62 watched the DFF video, 59 watched SL video, and 58 (control group) watched TW video. | Abstinence rates (DFF: 3%, SL 2%, Tw [control] 5%) were not significantly different from each other at 12 months follow‐up. There was no significant difference in validated abstinence artes between the video groups and the non‐participant group. | Expired CO<11 ppm. |

| Sutton 1988e | Fourth study (D) of the video studies groups provided a nested RCT. 161 continuing smokers at 3‐month follow‐up were randomised to intervention (79) or control (82). | 22% (7/32) of attenders in the intervention group were abstinent at 12 months, compared with 2% (1/47) of the non‐attending invitees, and compared with 2% (2/82)of the control group (p<0.001). | Expired CO<11 ppm. |

| Tanaka 2006 | Six intervention sites matched to 6 control sites; Of 1017 intervention smokers who completed baseline and 36m follow up, 125 participated in cessation campaign, and 79 accepted counselling + NRT. | 6m sustained abstinence at 36m ITT analysis was 8.9% (123/1382) intervention vs 7.0% (121/1736) control. Quit rates in both groups rose steadily over 36m. | No biochemical confirmation |

| Terazawa 2001 | 228 smokers randomized to intervention (117) or control (111). 25 smokers in the intervention group made a supported quit attempt | PP 11.1% (13/117) in the intervention group at 12m, compared with 1.8% (2/111) controls. Continuous abstinence 6.8% (8/117) intervention, compared with 0.9% (1/111) controls. Fisher's Exact test 2‐tailed P = 0.04 | Probably validated by expired CO |

| Willemsen 1998 | Four intervention worksites matched to 4 control sites (minimal self‐help), giving 498 smokers who completed baseline survey and enrolled in programmes. | Overall sustained abstinence quit rates at 6 months were 8% (9% for heavy smokers) in the comprehensive group, and 7% (4% for heavy smokers) in the minimal group (no p values given) | Self‐report, plus baseline Fagerstrom score. |

| Windsor 1988 | 387 smokers randomly assigned to four groups, in a 2x2 factorial pre‐/post‐test design. | As monetary incentives made no difference, groups 1&3 were compared with 2&4. Sustained abstinence at 1 year was 5.8% (11/190) in the self‐help only groups, and 14.4% (27/188) in the self‐help + counselling groups (p<0.001). | Baseline salivary cotinine, and follow‐up salivas at 6 weeks, 6 months and 1 year. |

Comparison 1 Results of included studies, Outcome 1 Results of included studies.

Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 1 Any behavioural therapy (various endpoints).

Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 2 Individual Counselling (various endpoints).

Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 3 Any self‐help intervention (various endpoints).

Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 4 Pharmacological Treatments (various endpoints).

Comparison 2 Individual Treatments, Outcome 5 Social support.

Comparison 3 Worksite Treatments, Outcome 1 Environmental support (various endpoints).

Comparison 3 Worksite Treatments, Outcome 2 Incentives (various endpoints).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Results of included studies Show forest plot | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Any behavioural therapy (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Individual Counselling (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 Any self‐help intervention (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4 Pharmacological Treatments (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5 Social support Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Environmental support (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Incentives (various endpoints) Show forest plot | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |