Tomografía de emisión de positrones (TEP) y resonancia magnética (RM) para la evaluación de la resecabilidad tumoral en el cáncer peritoneal/de las trompas de Falopio/ovárico epitelial primario avanzado

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

Additional references

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Aim of the study: to investigate the role of PET(‐CT) in characterisation of ovarian masses and identification of critical areas of tumour spread affecting results of debulking surgery Type of study: prospective study Enrolled/eligible: 29/23 Inclusion period: 2013 to 2014 | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Inclusion criteria: elevated serum CA125 and ultrasound detection of suspected ovarian malignancies Exclusion criteria: blood glucose levels > 140 mg/dL Mean age (range): 62 years (21 to 82) Setting: Gynaecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Instituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy | ||

| Index tests | Whole body FDG‐PET/CT Criteria to consider primary debulking unfeasible: involvement of porta hepatis, diffuse deep infiltration of root mesentery, diffuse carcinomatosis requiring complete colectomy or more than 4 bowel resections or total gastrectomy, deep infiltration of pancreas and duodenum, multiple liver metastases | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: debulking with no macroscopically visible tumour remaining after surgery Reference standard: all patients underwent explorative laparotomy and, where surgery was considered feasible, patients had primary debulking | ||

| Flow and timing | PET/CT was performed within 20 days of surgery. All patients received debulking surgery. 23 out of 29 patients were diagnosed with ovarian cancer and were eligible for analysis. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | Four patients had stage IC disease, 14 stage IIIC and three stage IV so it seems that two patients were missing in the stage description (n = 23). | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients diagnosed by conventional diagnostic work‐up for advanced stage cancer? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test PET/CT | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Did the whole sample, or a random selection of the sample, receive verification using a reference standard of diagnosis? | Yes | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | Yes | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in clinical practice? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the index test? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Unclear | ||

| Is the surgeon's expertise adequate to perform the reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Were withdrawals from the study reported? | Yes | ||

| Low | |||

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Aim of the study: to analyse the diagnostic accuracy of diffusion‐weighted MRI for predicting suboptimal cytoreductive surgery Type of study: prospective study Enrolled/eligible: 36/34 Inclusion period: 2006 to 2012 | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Inclusion criteria: patients undergoing surgery for suspected ovarian carcinoma Exclusion criteria: none Mean age (SD): 53 years (11) Setting: Gynaecology Department, Hospital Universitario Quiron, Madrid, Spain | ||

| Index tests | Pelvic and abdominal diffusion‐weighted MRI Criteria to consider primary debulking unfeasible: involvement of stomach, lesser sac, liver, small bowel mesentery, splenic hilium, para‐aortic lymph nodes above level of renal vessels | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: optimal debulking with residual disease of maximal 1 cm in diameter Reference standard: primary debulking surgery | ||

| Flow and timing | MRI was performed within 15 days of surgery. All patients received debulking surgery. 34 out of 36 patients had ovarian cancer and were eligible for analysis. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Unclear | ||

| Were the patients diagnosed by conventional diagnostic work‐up for advanced stage cancer? | Unclear | ||

| Were the patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | Unclear | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test MRI | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Did the whole sample, or a random selection of the sample, receive verification using a reference standard of diagnosis? | Yes | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | Yes | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in clinical practice? | No | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the index test? | Yes | ||

| Low | High | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Yes | ||

| Is the surgeon's expertise adequate to perform the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Were withdrawals from the study reported? | Yes | ||

| Low | |||

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Aim of the study: to evaluate ovarian cancer staging and tumour resectability with abdominal CT or MRI Type of study: prospective study Enrolled/eligible: 128 were enrolled of whom 82 underwent abdominal CT or MRI. 50/82 patients underwent MRI and were included in our analysis. Inclusion period: 1990 to 1994 | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Inclusion criteria: patients suspected of ovarian cancer scheduled for surgical staging Exclusion criteria: after inclusion, patients with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, benign disease, other intra‐abdominal malignancies, or those who had undergone surgery more than one month after MRI were excluded from the statistical analysis (n = 46) Mean age (range): 52 years (17 to 82) Setting: Department of Gynecologic Oncology, University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco, America | ||

| Index tests | MRI and/or abdominal CT. Patients undergoing MRI (with or without abdominal CT) were included in our analysis. Criteria to consider primary debulking unfeasible: tumour larger than 2 cm at root of mesentery, porta hepatis, omentum of lesser sac, intersegmental fissure of the liver, gastrosplenic ligament, diaphragm, dome of liver, enlarged lymph nodes around coeliac axis, and presacral extraperitoneal disease | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: debulking with residual disease < 2 cm Reference standard: primary debulking surgery | ||

| Flow and timing | MRI was performed within four weeks of surgery. All patients received debulking surgery. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | Patient scheduling was based on a variety of factors, including scheduling availability, preference of referring physician, and contraindications to abdominal CT or MRI. Also, there was a change in study design. From the initial 128 recruited patients, 82 patients underwent surgery and imaging and formed the study population. | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | No | ||

| Were the patients diagnosed by conventional diagnostic work‐up for advanced stage cancer? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Unclear | ||

| High | Unclear | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test MRI | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Did the whole sample, or a random selection of the sample, receive verification using a reference standard of diagnosis? | Yes | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | Unclear | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in clinical practice? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the index test? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Unclear | ||

| Is the surgeon's expertise adequate to perform the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Low | Unclear | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | No | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | No | ||

| Were withdrawals from the study reported? | Yes | ||

| High | |||

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Aim of the study: to evaluate whole body DW‐MRI for diagnosis, staging, and operability assessment of patients suspected for ovarian cancer compared to abdominal CT Type of study: prospective study Enrolled/eligible: 167/94 Inclusion period: 2010 to 2013 | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Inclusion criteria: ‐ suspicion of ovarian cancer by clinical assessment, serum CA‐125, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and gynaecological ultrasound, and ‐ staging by abdominal CT Exclusion criteria: contraindication for MRI Median age (range): 61 years (14 to 88) Setting: Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospitals, Leuven, Belgium | ||

| Index tests | Whole body diffusion‐weighted MRI Criteria to consider primary debulking unfeasible: extra‐abdominal distant metastasis, hepatic metastases, tumour infiltration of duodenum, stomach, pancreas, large vessels of coeliac trunk, hepatoduodenal ligament, metastases behind the portal vein, bowel involvement necessitating multiple bowel resections, deep tumoural involvement of superior mesenteric artery and root, retroperitoneal lymph node metastases above level of renal veins | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: debulking with no macroscopically visible tumour remaining after surgery Reference standard: explorative laparotomy, diagnostic laparoscopy or image‐guided biopsy of surgical‐critical distant lesions | ||

| Flow and timing | No information was provided about the time period between the index test and reference standard. All patients received (primary or interval) debulking surgery except for 4 patients who were medically unfit to undergo surgery. In patients where surgery was considered unfeasible, diagnostic laparoscopy was used as a reference standard to confirm irresectability. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients diagnosed by conventional diagnostic work‐up for advanced stage cancer? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test MRI | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Did the whole sample, or a random selection of the sample, receive verification using a reference standard of diagnosis? | Yes | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | No | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in clinical practice? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the index test? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Yes | ||

| Is the surgeon's expertise adequate to perform the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | No | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Were withdrawals from the study reported? | Yes | ||

| Unclear | |||

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Aim of the study: to develop a PET/CT‐based nomogram for predicting incomplete cytoreduction in advanced‐ovarian cancer patients. Type of study: retrospective study. A nomogram predicting incomplete debulking was constructed in a model development cohort (n = 240) and used in the validation cohort (n = 103). Enrolled/eligible: 343/343 Inclusion period: 2006 to 2012 | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Inclusion criteria: patients between 18 and 80 years with pathologically confirmed ovarian cancer FIGO stage III to IV undergoing cytoreductive surgery Exclusion criteria: patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, patients with history of other malignancies, and patients treated in another institute Median age (range): 55 years (27 to 80) Setting: Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea | ||

| Index tests | A nomogram including five FDG‐PET/CT features: involvement of diaphragm, small bowel mesentery, presence of ascites, peritoneal carcinomatosis, and tumoral uptake ratio and one non‐imaging related feature (an unvalidated surgical aggressiveness index) | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: macroscopic complete debulking Reference standard: primary debulking surgery | ||

| Flow and timing | PET/CT was performed within 4 weeks of surgery. Patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (due to poor physical condition for surgery or presence of extra‐abdominal disease) were excluded. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients diagnosed by conventional diagnostic work‐up for advanced stage cancer? | Yes | ||

| Were the patients planned for primary debulking surgery after conventional diagnostic work‐up? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test PET/CT | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Did the whole sample, or a random selection of the sample, receive verification using a reference standard of diagnosis? | Yes | ||

| Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result? | Yes | ||

| Were the same clinical data available when test results were interpreted as would be available when the test is used in clinical practice? | Unclear | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the index test? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Yes | ||

| Is the surgeon's expertise adequate to perform the reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did the study provide a clear definition of what was considered to be a ’positive’ result for the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Low | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Were withdrawals from the study reported? | Yes | ||

| Low | |||

CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen

CT: computed tomography

FDG: fluorodeoxyglucose‐18

FIGO: International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics

PET: positron emission tomography

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Other target condition. In patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis, MRI was used to evaluate tumour masses in the mesentery and bladder involvement. | |

| Study population: only one patient received primary debulking surgery after preoperative evaluation by PET‐CT. Also, Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Index was used as target condition instead of the completeness of debulking surgery. | |

| Other target condition. MRI was used to predict Peritoneal Cancer Index in patients being considered for cytoreductive surgery, of whom 5 were diagnosed with ovarian cancer. | |

| Other target condition. Peritoneal Cancer Index was estimated using PET‐CT to select patients for cytoreductive surgery or hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, of whom 7 were diagnosed with ovarian cancer. | |

| Required data could not be extracted from the published article and was not provided by study authors. | |

| Not a diagnostic test accuracy study | |

| Not a diagnostic test accuracy study |

CT: computed tomography

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

PET: positron emission tomography

Data

Presented below are all the data for all of the tests entered into the review.

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

| 1 PET/CT for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size Show forest plot | 2 | 366 |

| Test 1  PET/CT for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size. | ||

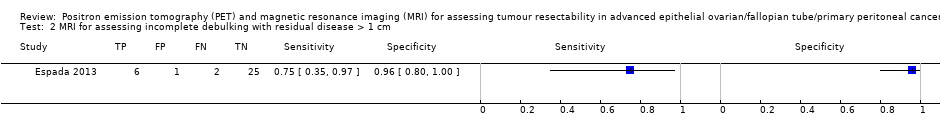

| 2 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 1 cm Show forest plot | 1 | 34 |

| Test 2  MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 1 cm. | ||

| 3 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 2 cm Show forest plot | 1 | 50 |

| Test 3  MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 2 cm. | ||

| 4 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size Show forest plot | 1 | 94 |

| Test 4  MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size. | ||

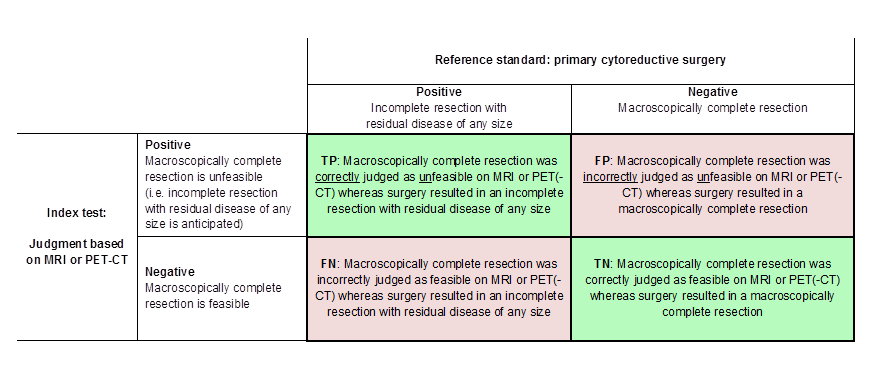

Definitions of the two by two table, wherein the index tests are tabulated against the reference standard outcome, on the analysis: macroscopic debulking versus incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size (i.e. consisting of deposits ≤ 1 cm and > 1 cm in diameter ). TP = true positive, FP = false positive, FN = false negative, TN = true negative.

Definitions of the two by two table, wherein the index tests are tabulated against the reference standard outcome, on the analysis: macroscopic debulking or incomplete debulking with residual disease ≤ 1 cm in diameter versus incomplete resection with residual disease > 1 cm in diameter. TP = true positive, FP = false positive, FN = false negative, TN = true negative.

Visual representation of 2 x 2 table. TP = true positive, FP = false positive, FN = false negative, TN = true negative.

Study flow diagram.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study

Forest plot of tests: 1 PET/CT for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size, 4 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size, 2 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 1 cm, 3 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 2 cm.

PET/CT for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size.

MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 1 cm.

MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 2 cm.

MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size.

| What is the diagnostic accuracy of FDG‐PET/CT or MRI for assessing tumour resectability in advanced epithelial ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal cancer? Patients Women suspected of ovarian cancer scheduled for surgery Prior testing Conventional diagnostic work‐up (e.g. physical examination, ultrasound) Setting University hospitals or specialised cancer institutes Index test FDG‐PET/CT or MRI. In all studies, the index test was evaluated as a replacement of abdominal CT. No studies were identified that followed an add‐on design. Target condition Residual disease assessed after debulking surgery | ||||||||

| Test | Target condition | No. of women (studies) | Prevalence in study | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | No. of false negatives* per 1000 tested | No. of false positives** per 1000 tested | Test accuracy certainty (quality) of evidence (sensitivity/specificity)a |

| FDG‐PET/CT | Residual disease > 0 cm | 23/343 (2) | 26%/65% | 1.0 (0.54 to 1.0) and 0.66 (0.60 to 0.73) | 1.0 (0.80 to 1.0) and 0.88 (0.80 to 0.93) | 211 (167 to 248)b | 46 (27 to 76)b | Lowc/moderated |

| DW‐MRI | Residual disease > 0 cm | 94 (1) | 53% | 0.94 (0.83 to 0.99) | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.00) | 37 (6 to 105)b | 8 (0 to 46)b | Lowc/moderated |

| DW‐MRI | Residual disease > 1 cm | 34 (1) | 23.5% | 0.75 (0.35 to 0.97) | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.00) | 59 (7 to 153) | 31 (0 to 153) | Very low/very low e, f |

| Conventional MRI | Residual disease > 2 cm | 50 (1) | 22% | 0.91 (0.59 to 1.00) | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.00) | 20 (0 to 90) | 23 (0 to 101) | Very low/very low e,g |

| CTh | Residual disease > 0 cm | 94 (1) | 53% | 0.66 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.78) | 0.77 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.87) | 211 (136 to 298)b | 87 (49 to 141)b | Low/lowc |

| CI: confidence interval a. According to GRADE for sensitivity (false negatives (FNs)) and specificity (false positives (FPs)), respectively | ||||||||

| Criteria to consider primary debulking unfeasible according to study methods | |||||

| Alessi | Shim | Espada | Forstner | Michielsen | |

| Site of tumour involvement | |||||

| Liver/porta hepatis | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Mesentery | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Colon | Yes, when necessitating > 4 bowel resections | No | No | No | Yes, when necessitating multiple bowel resections |

| Stomach | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Pancreas | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Duodenum | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Diaphragm | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Ascites | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Lesser sac/bursa omentalis | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Spleen/splenic hilum | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Lymph nodes above level of renal vessels/at coeliac axis | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gastrosplenic ligament | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Presacral extraperitoneal disease | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Extra‐abdominal distant metastasis | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Vessels of coeliac trunk | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Hepatoduodenal ligament | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Superior mesenteric artery | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Yes: site of tumour involvement is selected as one of the criteria to consider primary debulking unfeasible | |||||

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

| 1 PET/CT for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size Show forest plot | 2 | 366 |

| 2 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 1 cm Show forest plot | 1 | 34 |

| 3 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease > 2 cm Show forest plot | 1 | 50 |

| 4 MRI for assessing incomplete debulking with residual disease of any size Show forest plot | 1 | 94 |