Amitriptilina para la fibromialgia en adultos

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to studies awaiting assessment

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | R, DB, AC, PC, parallel groups, duration 12 weeks Medication taken once daily at 6 pm Assessment at baseline and 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion: women with fibromyalgia (ACR 1990), age 21 to 60 years, normal laboratory tests Exclusion: untreated inflammatory or endocrine disease; neurological, renal, infectious or bone disease; glaucoma, urinary retention, cardiovascular abnormalities; use of tricyclics within 3 months, any contraindication to study medication N = 38, mean age 43 years, all F Mean duration of symptoms > 33 months (least in placebo group, mean baseline pain 9/10 (5.7 to 9.6) | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 25 mg daily, n = 13 Panax ginseng extract (100 mg daily, 27% of ginsenosides), n = 12 Placebo, n = 13 Analgesics, opioids, anti‐inflammatory drugs all stopped for ≥ 3 weeks before start of study | |

| Outcomes | Mean pain intensity AE withdrawals | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of generation of random sequence not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | "identical form as capsules .... in sealed black bottles" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | "identical form as capsules .... in sealed black bottles" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Results for completers only |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

| Methods | Multicentre, R, DB, PC, parallel groups, duration 9 weeks Medication taken as single dose at bedtime. Initial daily dose of amitriptyline 10 mg, increased to 25 mg after 1 week, and to 50 mg after 4 weeks. Dose reduction allowed if not tolerated Pain, sleep, overall change in disease assessed at baseline, week 5 and week 9 | |

| Participants | Inclusion: primary fibrositis (Smythe's criteria) Exclusion: evidence of traumatic, neurologic, muscular, infectious, osseous, endocrine, or other rheumatic conditions. History of glaucoma, urinary retention, cardiovascular abnormalities. Use of amitriptyline within previous year N = 70 enrolled, 57 completed, mean age 41 years, M 5/F 54 Mean duration of symptoms ˜85 months (significantly longer in placebo group), mean baseline pain ˜6/10 | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 50 mg/day, n = 27 Placebo, n = 32 All NSAIDs, antidepressants and hypnotic medication stopped ≥ 3 weeks before start of study Paracetamol permitted throughout study | |

| Outcomes | Patient global impression of change Mean pain intensity Adverse events Withdrawals | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described ‐ stated to be "randomised" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Capsules "were identical" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Capsules "were identical" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Completer analysis |

| Size | High risk | Fewer than 50 participants/treatment arm |

| Methods | Multicentre, R, DB (DD), PC and AC, parallel groups, treatment period 24 weeks Amitriptyline taken as single dose at bedtime; initial daily dose 10 mg, increased to 25 mg after 1 week, and to 50 mg after 12 weeks. Cyclobenzaprine initial daily dose 10 mg at bedtime, increased to 20 mg at bedtime after 1 week, and to 10 mg in the morning +20 mg at bedtime after 12 weeks. Dose reduction permitted if not tolerated Pain, fatigue, sleep, fibromyalgia symptoms assessed at baseline, and each month | |

| Participants | Inclusion: fibromyalgia (ACR 1990), age ≥ 18 years, ≥ 4/10 for pain and/or global assessment of fibromyalgia symptoms Exclusion: evidence of inflammatory rheumatic disease, untreated endocrine, neurologic, infectious, or osseous disorder. Glaucoma, urinary retention, cardiovascular abnormalities. Previous treatment with study drugs N = 208, mean age 45 years, M 13/F 195 Median duration of symptoms 5 years, baseline pain ≥ 66/100 | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 50 mg/day, n = 84 Cyclobenzaprine 30 mg/day, n = 82 Placebo, n = 42 All NSAIDs, hypnotics, and antidepressants discontinued ≥ 3 weeks before start of study Paracetamol permitted throughout study | |

| Outcomes | Responder (at least 4/6 from ≥ 50% improvement in pain, sleep, fatigue, patient global assessment, physician global assessment, and increase of 1 kg in total myalgic score) Adverse events Withdrawals | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "generated using a table of random numbers .... assigned in blocks of 5" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double‐dummy method described. ''Either amitriptyline 25mg or an identical appearing inert cyclobenzaprine placebo or active cyclobenzaprine and inert amitriptyline placebo" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Double‐dummy method described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Responder analysis, but unclear whether withdrawal = non responder or LOCF |

| Size | High risk | Fewer than 50 participants in placebo treatment arm |

| Methods | Single centre, R, DB, PC, cross‐over study. 2 x 8‐week treatment periods with no washout. Medication taken as single dose, 1 hour before bedtime Pain, fibromyalgia, sleep, and fatigue assessed at baseline and end of each treatment period | |

| Participants | Inclusion: fibromyalgia (ACR), age ≥ 18 years, baseline pain and/or global assessment of fibromyalgia ≥ 4/10 Excluded: evidence of neurologic, muscular, infectious, endocrine, osseous, or other rheumatological diseases, history of glaucoma, urinary retention, cardiovascular disease, sleep apnoea N = 22, mean age 44 years, M 1/F 21 Mean (SD) duration of fibromyalgia 83 (± 75) months, mean baseline pain 7/10 | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 25 mg/d (reduced to 10 mg/day if not tolerated), n = 22 Placebo, n = 20 Washout before start of study: 2 weeks for NSAIDs and hypnotics, minimum 4 weeks for antidepressants Paracetamol permitted throughout study | |

| Outcomes | Responder (at least 4/6 from ≥ 50% improvement in pain, sleep, fatigue, patient global assessment, physician global assessment, and increase of 1 kg in total myalgic score) Mean pain intensity Withdrawals | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "generated using a table of random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | "identically appearing placebo tablet" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | "identically appearing placebo tablet" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All participants accounted for in responder analysis. Unclear how missing data were handled for mean data |

| Size | High risk | Fewer than 50 participants/treatment arm |

| Methods | R, DB (DD), AC, parallel groups, duration 6 weeks Medication taken as single dose at bedtime Assessment at baseline and end of treatment | |

| Participants | Inclusion: fibromyalgia (ACR), refractory to current treatment and PI ≥ 50/100 Exclusion: inflammatory rheumatic disease or other painful conditions that might confound assessment; history of substance abuse, neurologic or oncologic disease, ischaemic heart disease, kidney or hepatic insufficiency N = 63, mean age 48 years, mean baseline pain 66/100 | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 25 mg daily, n = 21 Melatonin 10 mg daily, n = 21 Amitriptyline 25 mg + melatonin 10 mg daily, n = 21 Current analgesics continued unchanged (paracetamol, ibuprofen, codeine, tramadol) Rescue medication: paracetamol (maximum 4 x 750 mg daily) and ibuprofen (maximum 4 x 20 mg daily) | |

| Outcomes | Pain intensity Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Use of additional analgesics in final week | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of sequence generation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Before the recruitment phase, envelopes containing the protocol materials were prepared. Each envelope was sealed and numbered sequentially" "Two investigators who were not involved in patient evaluations were responsible for the blinding and randomization procedures" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | "Placebo and active treatment [capsules] had the same size, color, smell and flavor" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | "Placebo and active treatment [capsules] had the same size, color, smell and flavor" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Imputation method for mean data unclear. No dichotomous data |

| Size | High risk | < 50 participants per treatment arm |

| Methods | Single centre, R, DB, PC, parallel groups, 8‐week treatment period Medication taken as single dose, 1 hour before bedtime Pain, fibromyalgia, sleep, and fatigue assessed at baseline and end of weeks 4 and 8 | |

| Participants | Inclusion: fibromyalgia (ACR) Exclusion: glaucoma, urinary retention, cardiovascular problems, epilepsy, treatment with amitriptyline within 6 months N = 46, mean age 46 years, M 8/F 38 Duration of fibromyalgia 0.3 to 20 years, mean baseline pain 7/10 | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 25 mg/day n = 24 (sustained‐release formulation) Placebo, n = 22 Not permitted during study: vitamin D/magnesium, muscle relaxants, analgesics/anti‐inflammatory except paracetamol, antidepressants, hypnotics, tranquillisers Paracetamol permitted throughout study for severe pain | |

| Outcomes | Responder (at least 3/4 from ≥ 50% improvement in patient global, physician global, pain, and ≥ 25% reduction in tender point score) Mean pain intensity Adverse events Withdrawals | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported ‐ stated as "randomly assigned" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Placebo was "identical to the amitriptyline capsules" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Placebo was "identical to the amitriptyline capsules" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All participants accounted for in responder analysis. Unclear how missing data were handled for mean data |

| Size | High risk | Fewer than 50 participants/treatment arm |

| Methods | R, DB (DD), AC, and PC, parallel groups, 6‐week treatment period Amitriptyline taken as single dose at night, naproxen as divided dose morning and night ‐ implication is DD Assessments at baseline, 2, 4, and 6 weeks for patient global fibromyalgia symptoms, pain or stiffness, fatigue, sleep | |

| Participants | Inclusion: fibromyalgia (not ACR, but probably equivalent), baseline pain and/or fibromyalgia symptoms ≥ 4/10 Excluded: peptic ulcer disease or cardiac arrhythmias N = 62, mean age 44 years, M 3/F 59 Duration of chronic pain 0.3 to 20 years | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 25 mg/day, n = assume 16 Naproxen 2 x 500 mg/day, n = assume 15 Amitriptyline 25 mg + naproxen 2 x 500 mg/day, n = assume 15 Placebo, n = assume 16 All analgesics, anti‐inflammatory medications, antidepressants, sleeping medication and CNS‐active medications stopped ≥ 72 h before start Paracetamol (2 x 650 mg every 4 hours) allowed for severe pain throughout study | |

| Outcomes | Mean pain intensity Withdrawals | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported ‐ stated to be "randomly assigned" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Stated to be 'blinded'. Describes double‐dummy design but not stated to be matching |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Stated to be 'blinded'. Describes double‐dummy design but not stated to be matching |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. No responder data |

| Size | High risk | Fewer than 50 participants/treatment arm |

| Methods | Single centre, R, DB, PC, and AC, cross‐over study. 4 x 6‐week treatment periods with 2‐week washout between periods. Amitriptyline taken as single dose at bedtime, fluoxetine as single dose in the morning Pain, fibromyalgia, sleep, and fatigue assessed at baseline and end of each treatment period | |

| Participants | Inclusion: fibromyalgia (ACR), age 18 to 60 years, baseline pain ≥ 30/100, baseline HRS‐D ≤ 18 Exclusion: current or history of systemic disease N = 31, mean age 43 years, M 3/F 28 Duration of symptoms 24 to 240 months, mean baseline pain 67/100 | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 25 mg/day, n = 21 Fluoxetine 20 mg/day, n = 22 Amitriptyline 25 mg + fluoxetine 20 mg, n = 19 Placebo, n = 19 All CNS‐active medications, NSAIDs, analgesics other than paracetamol stopped ≥ 7 days before start Paracetamol permitted | |

| Outcomes | Mean pain intensity Withdrawals | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "order of treatment was generated from a table of random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | "All tablets were identical in appearance" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | "All tablets were identical in appearance" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | LOCF implied |

| Size | High risk | Fewer than 50 participants/treatment arm |

| Methods | Multicentre, R, DB, PC, and AC, parallel groups, 12‐week treatment period Amitriptyline taken 2 h before bedtime, moclobemide taken as divided dose in morning and afternoon. Initial daily dose amitriptyline 12.5 mg, increased to 25 mg at 2 weeks, and again to 37.5 mg at 6 weeks if response unsatisfactory. Initial daily dose of moclobemide 300 mg, increased to 450 mg at 2 weeks, and again to 600 mg if response unsatisfactory Pain, general health (fibromyalgia), sleep, and fatigue assessed at baseline and 2, 6, 12 weeks | |

| Participants | Inclusion: fibromyalgia (ACR 1990), female, age 18 to 65 years, score ≥ 4/10 for at least three of pain, general health (fibromyalgia), sleep, and fatigue Exclusion: severe cardiovascular, pulmonary, hepatic, haematological or renal disease N = 130, mean age 49 years, all F Mean duration of symptoms 8 years, baseline pain ≥ 5.7/10 | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 25 mg/day, n = 42 Moclobemide 450 mg/day, n = 43 Placebo, n = 45 All CNS‐active medications, NSAIDs, and analgesics (other than paracetamol) discontinued before start of study Paracetamol permitted throughout study | |

| Outcomes | Mean pain intensity, global health Adverse events Withdrawals | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | ''The randomisation was organised centrally with sequentially numbered envelopes consisting of blocks of six''. Probably low risk |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Does not state that envelopes were opaque |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | "placebo capsules were identical to the active drugs". Implies double‐dummy method |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | "placebo capsules were identical to the active drugs". Implies double‐dummy method |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Imputation method not reported. No obvious imbalance for discontinuations between groups, but > 25% withdrawals in all groups |

| Size | High risk | Fewer than 50 participants/treatment arm |

AC: active control; ACR: American College of Rheumatology; BOCF: baseline observation carried forward; CNS: central nervous system; DB: double‐blinding; DD: double dummy; ECG: electrocardiogram; HRS‐D: Hamilton Rating Scale ‐ Depression; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; LOCF: last observation carried forward; NSAIDs: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; PC: placebo controlled; PDN: painful diabetic neuropathy; PHN: postherpetic neuralgia; R: randomisation; W: withdrawals

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| No initial pain requirement for inclusion, no baseline pain reported | |

| Fewer than 10 participants in amitriptyline treatment arm | |

| No initial pain requirement for inclusion, no baseline pain reported | |

| Study not blinded | |

| Fewer than 10 participants/treatment group (N of 1 trials) | |

| Fewer than 10 participants/treatment group | |

| Predominantly neuropathic or musculoskeletal pain | |

| Neuropathic pain | |

| Unclear diagnosis of pain condition ("a wide range of intractable pain problems ..... without readily treatable somatic pathology") | |

| Study not double‐blind | |

| No initial pain requirement for inclusion, no baseline pain reported | |

| Unclear diagnosis of pain condition ("somatoform pain disorder"). Included some participants with < moderate baseline pain intensity | |

| Unclear diagnosis of pain condition ("chronic pain .....no selection on organic or psychogenic aetiology"). Included some participants with < moderate baseline pain intensity | |

| No pain evaluation, duration of each treatment period only 2 weeks | |

| Study not convincingly double‐blind, no patient evaluation of pain |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised, 6‐week trial |

| Participants | Fibromyalgia N = 68 |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline Paroxetine |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | Turkish (with English abstract) ‐ awaiting translation |

| Methods | Randomised, controlled trial, 4 weeks |

| Participants | Fibromyalgia syndrome N = 186 |

| Interventions | Oral amitriptyline (Western medicine), once daily Acupuncture combined with cupping and Western medicine Acupuncture combined with cupping |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | Chinese (with English abstract) ‐ awaiting translation |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, cross‐over study. Duration 43 days (possibly 2 x 3 weeks) Assessment at 1, 15, 29, 43 days |

| Participants | Fibromyalgia (ACR 1990) with self‐reported sleep disturbance. Age 18 years or over N = 32 |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 10 to 25 mg daily Nabilone 0.5 to 1 mg daily |

| Outcomes | Pain intensity (VAS) Pain quality (McGill Pain Questionnaire) Quality of Life (Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire) Mood (Profile of Mood States) |

| Notes | Reported complete in May 2007 |

ACR: American College of Rheumatology; N: number of participants; VAS: visual analogue scale

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

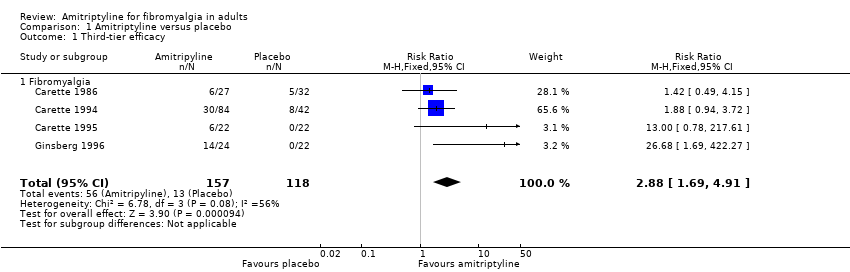

| 1 Third‐tier efficacy Show forest plot | 4 | 275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [1.69, 4.91] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 1 Third‐tier efficacy. | ||||

| 1.1 Fibromyalgia | 4 | 275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [1.69, 4.91] |

| 2 At least 1 adverse event Show forest plot | 4 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.54 [1.29, 1.84] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 2 At least 1 adverse event. | ||||

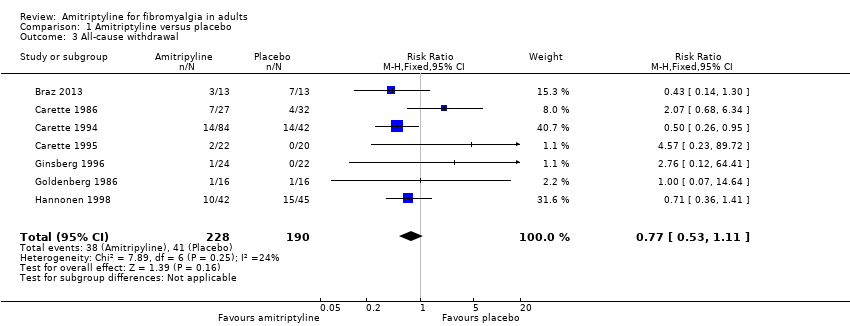

| 3 All‐cause withdrawal Show forest plot | 7 | 418 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.53, 1.11] |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 3 All‐cause withdrawal. | ||||

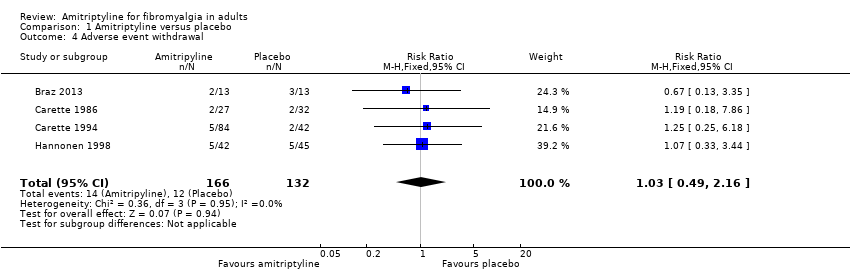

| 4 Adverse event withdrawal Show forest plot | 4 | 298 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.49, 2.16] |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 4 Adverse event withdrawal. | ||||

| 5 Lack of efficacy withdrawal Show forest plot | 3 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.19, 0.95] |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 5 Lack of efficacy withdrawal. | ||||

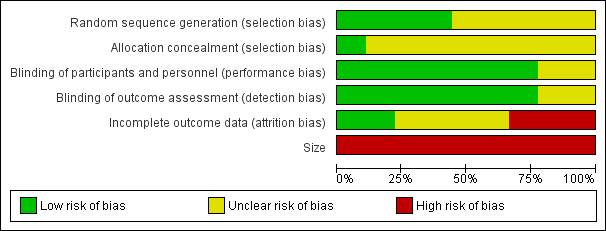

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Third‐tier efficacy.

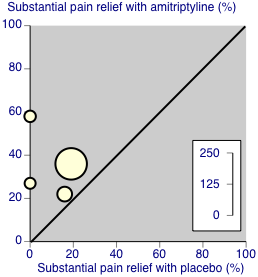

Third‐tier evidence: substantial pain relief

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 1 Third‐tier efficacy.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 2 At least 1 adverse event.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 3 All‐cause withdrawal.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 4 Adverse event withdrawal.

Comparison 1 Amitriptyline versus placebo, Outcome 5 Lack of efficacy withdrawal.

| Amitriptyline compared with placebo for fibromyalgia | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with fibromyalgia Settings: community Intervention: amitriptyline 25 to 50 mg daily Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Probable outcome with intervention | Probable outcome with placebo | NNT or NNH and/or relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments |

| At least 50% reduction in pain or equivalent (substantial) | 360 in 1000 | 110 in 1000 | RR 2.9 (1.7 to 4.9) NNT 4.1 (2.9 to 6.7) | 4 studies, 275 participants | Very low | Small number of studies and participants |

| At least 30% reduction in pain or equivalent (moderate) | no data | |||||

| Adverse event withdrawals | 80 in 1000 | 90 in 1000 | RR 1.03 (0.49 to 2.2) NNTp not calculated | 4 studies, 298 participants | Very low | Small number of studies and participants |

| Serious adverse events | none reported | |||||

| Death | none reported | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Third‐tier efficacy Show forest plot | 4 | 275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [1.69, 4.91] |

| 1.1 Fibromyalgia | 4 | 275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [1.69, 4.91] |

| 2 At least 1 adverse event Show forest plot | 4 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.54 [1.29, 1.84] |

| 3 All‐cause withdrawal Show forest plot | 7 | 418 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.53, 1.11] |

| 4 Adverse event withdrawal Show forest plot | 4 | 298 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.49, 2.16] |

| 5 Lack of efficacy withdrawal Show forest plot | 3 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.19, 0.95] |