肺癌と診断された患者の禁煙のための介入

Referencias

References to studies excluded from this review

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| RCT comparing telephone counselling plus tailored self directed materials with tailored self directed materials alone. The participants were not people with lung cancer | |

| RCT comparing telephone counselling plus tailored self directed materials with tailored self directed materials alone. The participants were not people with lung cancer | |

| Not an RCT | |

| No control group, not randomised | |

| Completed in 2004. No results were available. We were unable to get in touch with the authors to request the protocol or the results | |

| It reports the study as "randomized" but it is also described as "Phase 1" (which is not an RCT). There was no clear description of the experimental intervention or the comparator on the website. It probably was not an RCT. We were unable to get in touch with the authors to request the protocol and or any results | |

| Unable to distinguish people with lung cancer from other participants | |

| Unable to distinguish people with lung cancer from other participants | |

| Unable to distinguish people with lung cancer from other participants | |

| No control group, not randomised |

RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Trial name or title | Studies Examining the Importance of Smoking After Being Diagnosed With Lung Cancer |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised Endpoint classification: efficacy study Intervention model: single group assignment Masking: open label Primary purpose: treatment |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

| Interventions | Experimental: intensive quit smoking support Active comparator: physician advice to quit |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome:

Secondary outcome:

|

| Starting date | March 2010 |

| Contact information | Rachel E Roberts, BSc Telephone: +44 1554756567 ext 3569 Email: [email protected] |

| Notes | www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01192256 |

| Trial name or title | Feasibility of Delivering a Quitline Based Smoking Cessation Intervention in Cancer Patients |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

| Interventions | Experimental: nicotine replacement patch |

| Outcomes |

|

| Starting date | October 2011 |

| Contact information | US, North Carolina W F Baptist Health Winston Salem, North Carolina, US, 27157 |

| Notes | www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01434342 |

| Trial name or title | Smoking Cessation Strategies in Community Cancer Programs for Lung and Head and Neck Cancer Patients |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised Endpoint classification: efficacy study Intervention model: parallel assignment Masking: open label Primary purpose: treatment |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

| Interventions |

|

| Outcomes | Cigarette use (time frame: 8 weeks) |

| Starting date | July 2014 |

| Contact information | Kris Damron Telephone: 859‐323‐1109 Email: [email protected] |

| Notes | www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02048917 |

AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer; C‐SRSS: Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status; NRT: nicotine replacement therapy; NSCLC: non‐small‐cell lung carcinoma; PRN: as needed; WHO: World Health Organization.

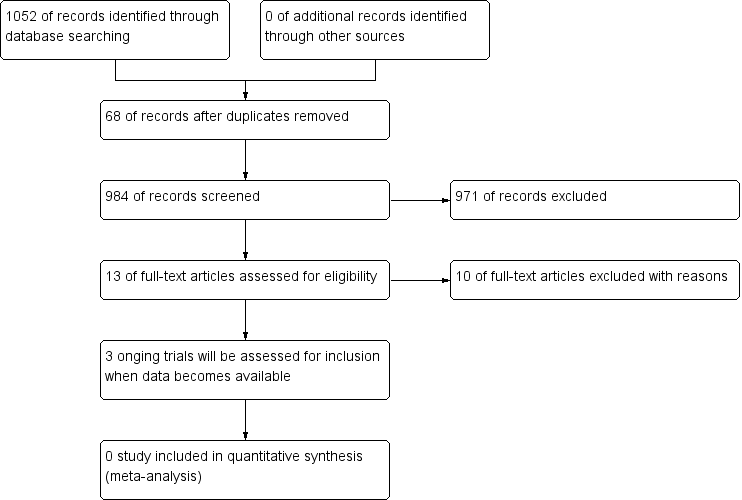

Study flow diagram.