Services de télérééducation après les accidents vasculaires cérébraux

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to studies awaiting assessment

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from University Medical Centre in the USA Inclusion criteria: fully oriented; able to follow a 3‐step command; evidence of stroke on neuroimaging or hemiparetic. Caregivers were defined as family or friends living with survivors or within a 30‐minute driving distance and acting as the primary source of assistance for survivors. Exclusion criteria: < 35 years old; subarachnoid haemorrhage; psychosis; lack of a caregiver; admission from a nursing home; non‐English speaking Age, years: mean (SD) 70.1 (11.6) Gender: 35% men Time post‐stroke: not reported but conducted on discharge home from hospital | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: Family Intervention Telephone Tracking (FITT) which focuses on 5 key areas: (1) family functioning, (2) mood, (3) neurocognitive functioning, (4) functional independence, and (5) physical health. Telephone contacts took place during the 6‐month transition period after discharge from an acute care setting, with the FITT intervention formally beginning when stroke survivors arrived home. FITT contacts occurred weekly for 6 weeks, biweekly for the next 2 months, and then monthly for 2 months, for a total of 13 calls to each individual (26 calls per dyad). Calls were made by clinicians who came from different professional backgrounds (medical practitioner, nurse, and family therapist) Control intervention: usual care | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, 3 months, 6 months Measures: healthcare utilisation (direct report), Frenchay Activities Index; Geriatric Depression Scale; Family Assessment Device; Perceived Criticism Scale | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Used urn randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Detail not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Assessors were blinded to group allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Details of dropouts not clearly reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No mention of protocol or trial registration |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from patients discharged from inpatient stroke rehabilitation in Slovenia Inclusion criteria: stroke, requiring help with ADLs (FIM score 40 to 80) Exclusion criteria: orthopaedic problems, other neurological diseases and severe health complications that would prevent participation Age: intervention group mean 70, control group mean 63 Gender: intervention group 60% men, control group 40% men Time post‐stroke: intervention group mean 8.2 months, control group mean 5.1 months | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation: participants were taught how to use a computer tablet and access selected videos on a web portal. Training focused on posture and exercises for the neck, shoulders, torso, and upper limbs. The participant was asked to do exercises daily 3 months after discharge from the rehabilitation setting. Therapists interviewed the participant and relatives once a week during which they checked adherence to exercises, answered questions, monitored progress, and adjusted the content of the exercise programme, as required. Control intervention: classified as usual care. Were provided with oral and written instructions for similar exercises. The person was instructed to do the exercises of their choice and abilities 1 to 2 times per day. | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline and 3 months after randomisation Measures: joint flexibility, Modified Ashworth Scale, Visual Analogue Scale for Pain Assessment, Motor Assessment Scale, Wolf Motor Function Test, Fugl Meyer Assessment | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Unable to determine |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided about whether or not there were withdrawals |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol or trial registration available |

| Other bias | Low risk | None noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from 12 hospitals in the Netherlands Inclusion criteria: Dutch speaking, ≥ 18 years of age, first admission for a stroke, hospitalisation within 72 hours after onset of symptoms, life expectancy > 1 year, independent from or partially dependent on discharge (Rankin grade 0 to 3), discharged home, residence within 40 kilometres of catchment areas served by hospitals Exclusion criteria: failure to meet above criteria Age, years: intervention group median (IQR) = 66 (52 to 76), control group median (IQR) = 63 (51 to 74) Gender: intervention group 49% men, control group 48% men Time post‐stroke: not reported | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: 3 nurses initiated telephone contacts (1 to 4; 4 to 8; and 18 to 24 weeks after discharge) and visits to participants in their homes (10 to 14 weeks after discharge). Stroke nurses used a standardised checklist of risk factors for stroke, consequences of stroke and unmet needs for services. Nurses supported participants and caregivers according to their individual needs (e.g. by providing information or reassurance) or advised participants to contact their GP when further follow‐up was required. Written educational material was provided and discussed. Nurses aimed to support participants and caregivers in solving problems themselves or coping with them rather than solving problems for them. Control intervention: standard care | |

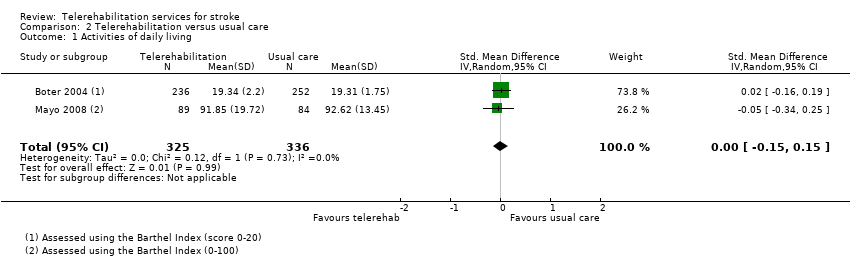

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline and post‐intervention (6 months after discharge) Measures: Barthel Index, Rankin Grade, Satisfaction with Stroke Care questionnaire, SF‐36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, health‐service utilisation (GP), readmissions, therapy, activities of daily living care, rehabilitation, aids, secondary prevention drugs, caregiver questionnaires | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerised programme |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central telephone service used |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessor was blinded to allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Additional data collected at 6 months and not reported in the paper |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unable to identify further bias |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from the community via advertising in a local paper and local stroke support group meetings in the USA Inclusion criteria: more than 12 months post‐stroke, between 30 and 80 years old, satisfactory corrected vision to recognise the full tracking target and cursor movement, ≥ 90 degrees of passive extension‐flexion movement at the index finger metacarpophalangeal joint of the paretic hand (no contracture) and at least 10 degrees of active movement at this joint Exclusion criteria: unable to undergo fMRI, pregnancy, or claustrophobia Age, years: intervention group (Track) mean = 65.9 (SD 7.4), intervention group (Move) mean = 67.4 (SD 11.8) Gender: intervention group (Track) 90% men, intervention group (Move) 60% men Time post‐stroke: intervention group (Track) mean 42.5 months (SD 24.3), intervention group (Move) mean 35.6 months (SD 26.1) | |

| Interventions | Both groups received telerehabilitation. The aim of the intervention was to practice finger and wrist movements. Training was completed on a laptop using customised tracking software without direct supervision by the therapist. Both groups performed 180 tracking trials per day for 10 days. Regular teleconferencing (mobile phone and Webcam operating over the Internet) occurred between therapist and participant. Telerehabilitation intervention (Track group): tracking software provided feedback and an accuracy score Telerehabilitation intervention (Move group): tracking software showed a sweeping cursor representing movement, however did not provide the target or response or an accuracy score | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline and post‐intervention Measures: Box and Block test, Jebsen Taylor test, finger ROM, finger movement tracking test, fMRI | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Substantial loss of participants at follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No protocol available |

| Other bias | High risk | Small sample size and considerable differences between groups in mean values on some outcome measures at baseline, although these differences were not statistically significant |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from a Hospital in Shanghai, China Inclusion criteria: aged 35 to 85 years old; first diagnosis was ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke or recurrent stroke but without hemiplegia symptoms before; have a symptom of hemiplegia, left or right; 14 to 90 days from stroke onset; National Institute of Health Stroke Scale scores from 2 to 20 and mRS scores from 1 to 5; have not previously received any rehabilitation intervention since this stroke onset Exclusion criteria: Glasgow Coma Scale scores under 15, have been confirmed as having dementia based on Mini Mental State Examination assessment, with mental disorders and unable to cooperate with examination, treatment or follow‐up; disability not induced by stroke or disability induced by historical stroke; associated severe primary disease of heart, liver, kidney, or haematological system; cognitive disorder, history of psychosis, substance abuse, or alcoholism; skin infections in the areas of surface electrodes attached; metal implants in the body, including cardiac pacemaker, metal stent, or steel plate; in the gestation or lactation period or have a fertility plan; associated malignant tumour or severe progressive disease in any other system; have been recruited by any other clinical trial in the preceding 90 days; unable to complete the basic course of treatment, with poor treatment adherence or inability to follow‐up Age, years: intervention group mean 66.5 SD (12.1), control group mean 66.2 SD (12.3) Gender: 67% men Time post‐stroke: intervention group mean (SD) 25.0 (5.6) days, control group 26.9 (4.7) days | |

| Interventions | After discharge, participants in both groups were given physical exercises and electromyography‐triggered neuromuscular stimulation (ETNS). Exercises were conducted for 1 hour, twice in a working day for 12 weeks (total = 60 sessions). ETNS was conducted by using a portable muscle electricity biofeedback instrument for 20 minutes, twice in a working day for 12 weeks, a total of 60 sessions. Telerehabilitation intervention: Individualised telerehabilitation physical exercise plan selected by treating therapists and provided as prescription within the telerehabilitation apparatus. Therapists explained and demonstrated exercises. After discharge, participants received rehabilitation via the telerehabilitation system; therapists supervised via live video and collected data remotely. Therapists were available for advice if needed. Carers kept training logs of training. Control intervention: received rehabilitation in the outpatient therapy department. Exercises and ETNS were the same but the therapy was provided face‐to‐face with therapists. | |

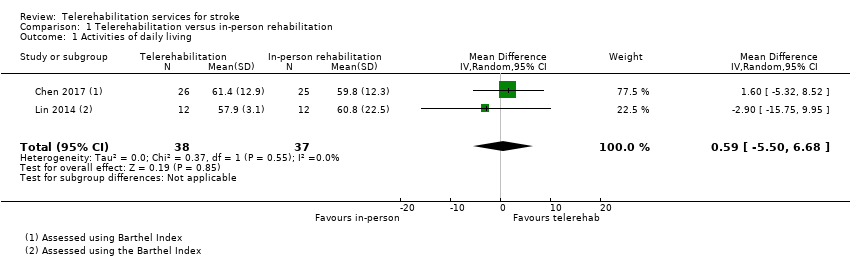

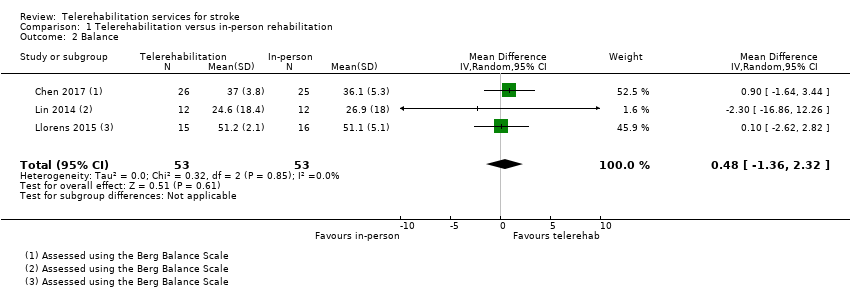

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, 12, and 24 weeks after randomisation Measures: Modified Barthel Index; Berg Balance Scale; mRS; Caregiver Strain Index; Root Mean Square | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated sequence |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Held in opaque sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Few withdrawals, even across groups, and reasons reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Trial registered and all outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from 3 Veterans Affairs Medical Centres in the USA Inclusion criteria: ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke within the previous 24 months; participants aged 45 to 90 years, discharged to the community, not cognitively impaired (no more than 4 errors on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire), able to follow a 3‐step command, discharge motor Functional Independence Measure score of 18 to 88, approval by participants and physician; signed medical media release form Exclusion criteria: failure to meet above criteria Age, years: intervention group: mean = 67.1 (SD 9.5), control group: mean = 67.7 (SD 10) Gender: intervention group: 96% men; control group: 100% men Time post‐stroke: intervention group median 26 days, control group median 74 days | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: the purpose of the intervention was to improve the participant's functional mobility. Intervention included 3 tele‐visits, use of an in‐home messaging device (IHMD) and 5 telephone calls over a 3‐month period. The tele‐visits involved assessment of physical function, goal‐setting and demonstration of exercises; a research assistant used a camcorder to record the home environment and the participant completing tests of physical and functional performance that were later reviewed by the teletherapist. The therapist asked the participant questions via the IHMD and provided positive encouragement to maximise exercise adherence. Telephone calls were used to problem‐solve any barriers to exercise and to review and advance the exercise programmes. Control intervention: usual care | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, post‐intervention (3 months) and 6 months Measures: motor subscale of the Functional Independence Measure (telephone version), Late Life Function and Disability Instrument, stroke‐specific participant satisfaction with care questionnaire, Falls Self‐Efficacy Scale | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated sequence |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Centralised computer program |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | ITT analyses completed. Small numbers of missing data, which were explained and balanced across groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | The publication does not present the results for all outcome measures listed in the study protocol. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unable to identify further bias |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from: 11 sites in the USA Inclusion criteria: age ≥ 18 years, stroke onset 4 to 36 weeks prior, arm motor Fugl‐Meyer score 22‐56 (out of 66) Exclusion criteria: major active coexistent neurological or psychiatric disease; severe depression, cognitive impairment (MoCA < 22), communication deficits interfering with participation, life expectancy < 6 months, non‐English speaking, unable to perform the 3 rehabilitation exercise test examples Age, years: intervention group mean age 62 (14), control group 60 (13) Gender: 73% men Time post‐stroke: intervention group mean 132 (65) days, control group 129 (59) days | |

| Interventions | Participants in both groups were offered 36 sessions (18 supervised, 18 unsupervised) lasting for 70 minutes each over 6 to 8 weeks. All participants signed a behavioural contract that included a treatment goal and treatment was based on an upper extremity task‐specific training manual and accelerated skill acquisition programme. Telerehabilitation intervention: rehabilitation treatment sessions via an in‐home internet‐connected computer. The participant performed daily assigned home‐based telerehabilitation exercises and functional training (including use of games and input devices such as PlayStation Move Controller) and 5 minutes of stroke education, all guided by the telerehabilitation system. During half of the sessions, therapists initiated a video conference with the participant's telerehabilitation system to discuss progress, issues, and revise treatment plans as needed. Control intervention: same intensity, duration, and frequency of therapy and stroke education content but provided in clinic with therapist feedback based on observations on supervised days | |

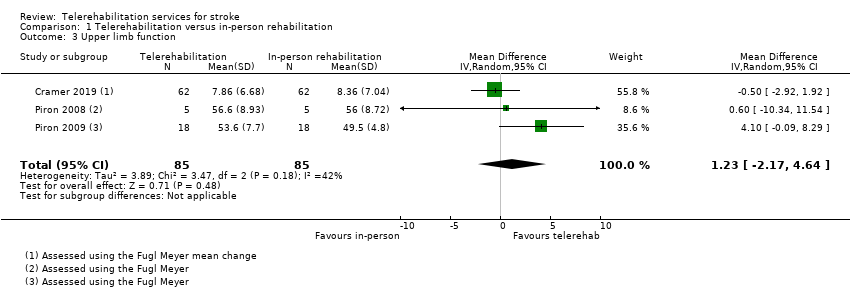

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, 30 days after randomisation Measures: Fugl‐Meyer Arm, Box and Block test, Stroke Impact Scale‐Hand Domain | |

| Notes | NCT02360488 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation schedule developed at the StrokeNet National Data Management Centre |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Web‐based central randomisation system |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Low number of withdrawals and balanced across groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Trial registered |

| Other bias | Low risk | None noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from the community. Study conducted in the USA Inclusion criteria: post‐stroke duration of at least 5 months, at least 10 degrees of active dorsiflexion/plantar flexion at the paretic ankle, ability to understand the tasks, ability to ambulate 30 metres Exclusion criteria: indwelling devices incompatible with MRI Age, years: telerehabilitation (Track) group mean = 51.4 (SD 11.5), telerehabilitation (Move) group mean = 58 (SD 13.4) Gender: Track group 38% men; Move group 100% men Time post‐stroke: Track group median 66 months; Move group median 16.5 months | |

| Interventions | Both groups received telerehabilitation. The aim of the intervention was to practice ankle movements. Training was completed on a laptop using customised tracking software without direct supervision by the therapist. Both groups performed 180 repetitions for 20 days. Regular teleconferencing using Skype occurred between the therapist and the participant, and the computer automatically emailed daily records to the laboratory computer to allow monitoring of performance. Telerehabilitation intervention (Track group): tracking software provided feedback and an accuracy score. Telerehabilitation intervention (Move group): tracking software showed a sweeping cursor representing the movement; however, did not provide the target or response or an accuracy score. | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline and post‐intervention Measures: gait analysis, 10‐metre walk test, fMRI | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Electronically‐generated randomisation list |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clearly reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Attrition reported with reasons and similarities between groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No access to protocol |

| Other bias | High risk | Small sample size |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruitment details unclear. Study took place in the USA. Inclusion criteria: first time medical diagnosis of acute stroke, onset of stroke was at 6 or fewer months, Medicare or Blue Cross and Blue Shield insurance coverage, moderate deficits in the areas of self‐care, functional mobility, transfers as documented by the Functional Independence Measure, caregiver present to set up telehealth videophone device Exclusion criteria: aphasia or major depressive disorder, as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory II Age, years: mean age of all participants was 60 Gender: 55% men Time post‐stroke: not reported | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: 12 treatment sessions (6 occupational therapy and 6 physiotherapy) were provided over approximately 6 weeks. Interventions included education, retraining of self‐care, functional mobility and posture, home modifications and therapy to improve function in impaired limbs. Communication between therapist and participant occurred via a desktop videophone using standard telephone lines Control intervention: included the same content; however, was delivered in‐person | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline and post‐intervention Measures: Functional Independence Measure, SF‐12 | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Lack of detail in reporting the results |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not able to access protocol |

| Other bias | High risk | Small sample size |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from a rehabilitation service in the Netherlands Inclusion criteria: age > 18 years; established diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, stroke or traumatic brain injury; taking more than 25 seconds to perform the Nine‐Hole Peg Test, ability to move at least 1 peg in 180 seconds during the Nine‐Hole Peg Test, sufficient autonomous functioning, Internet connection or telephone line and reachable Internet provider, stable clinical status, living at home Exclusion criteria: disturbed upper limb function not related to multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury or stroke; serious cognitive and/or behavioural problems, major visual problems, communication problems, medical complications; other problems, possibly contraindicating autonomous exercise at home Age, years: telerehabilitation group mean = 69 (SD 8), control group mean = 71 (SD 7) Gender: telerehabilitation group 18% men, control group 80% men Time post‐stroke: telerehabilitation group mean 3 (SD 2) years, control group mean 1.8 (SD 0.8) years | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: 1 month of usual care followed by approximately 4 training sessions with the Home Care Activity Device (HCAD) system in the hospital and intervention using the HCAD for 1 month. The system comprised a hospital‐based server and the portable unit installed at the participant's home. The portable unit consisted of 7 sensorised tools; a key, a light bulb, a book, a jar, writing, checkers and keyboard. The unit also had 2 webcams that allowed videoconferencing and recording. It was recommended that participants use the HCAD at least 5 days per week for 30 minutes. Control intervention: usual care and generic exercises prescribed by the physician | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline and post‐intervention Measures: Barthel Index, participant satisfaction assessed using visual analogue scale, SF‐36, Action Research Arm Test, Nine‐Hole Peg Test, Wolf Motor Function Test, grip strength, Abilhand | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Randomisation scheme generated using 2:1 allocation ratio. Participants allocated to the study when the intervention was available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Dropouts were reported and ITT analyses conducted |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Some study data not reported in the published paper |

| Other bias | High risk | Small sample size Differences between groups at baseline |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from six hospitals in the USA Inclusion criteria: within 4 months of an ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke (verified by CT or MRI) with clinical depression (≥ 11 on the Geriatric Depression Scale) Age, years: intervention (telephone) group mean 61.7, intervention group (in‐person) 58.5, control group 60.7 Gender: 50% men Time post‐stroke: not reported | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: 'Living Well With Stroke 2 intervention': 1 in‐person orientation session with the psychosocial nurse practitioner therapist, either in their home or at the study offices. They received the participant manuals and discussed goals and expectations. Following the in‐person orientation session, each of the subsequent 6 sessions occurred by telephone. Topics were as follows: (1) introduction to behavioural therapy for depression after stroke, pleasant events; (2) scheduling pleasant events: problems and planning; (3) managing depression behaviours: problem‐solving techniques; (4) changing negative thoughts and behaviours; (5) problem‐solving in depth; (6) review of skills, generalisation and strategies for maintenance of skills. Session length ranged from 10 to 80 minutes, with the telephone sessions somewhat shorter than the in‐person ones (average 26 minutes versus 38 minutes). Participants in the intervention arms saw their primary care or stroke provider for stroke follow‐up care and were provided antidepressants as prescribed by their providers. In‐person intervention: same 'Living Well With Stroke 2' intervention but provided in‐person (usually in the participant's home) Control intervention: usual care | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, post‐intervention (8 weeks), 21 weeks, and 12 months Measures: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Stroke Impact Scale and perceived recovery | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerised procedure using modified version of the minimisation method |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Managed online by research nurses and statistician |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Low number of withdrawals; balanced across groups and explained clearly |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Trial registered ahead of time on clinical trial register. Published paper did not present results of Stroke Impact Scale or perceived recovery. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from 3 long‐term care facilities (LTCFs) in Taiwan Inclusion criteria: history of cerebral vascular accident (including first and recurrent stroke) for more than 6 months; living in LTCFs for more than 3 months; having active movement of the proximal part of upper extremity in the hemiparetic side (Brunnstrom stage U/E ≥ 3); being able to sit for short periods without hand support for at least 30 seconds; having cognitive status screened using the Mini‐Cog test and being able to follow the instruction; and being able to communicate and follow a 3‐step command Exclusion criteria: having other neuromusculoskeletal condition and systemic diseases such as Parkinson's disease and uncontrolled heart disease; blindness and deafness; and having a psychiatric history Age, years: intervention group mean 74.6 (SE 2.3), control group 75.6 (SE 3.4) Gender: 71% men Time post‐stroke: not reported | |

| Interventions | The treatment programme for both groups included 3 sessions of training per week for 4 weeks, with the duration of approximately 50 minutes for each session. The therapist instructed standing balance training from easy to difficult, depending on the severity and recovery of the participants. Telerehabilitation intervention: the tele‐balance training focused on 10 minutes of standing exercise according to 3D animation exercise videos and about 10 minutes of 3D interactive games with finger touching the touch screen in standing posture. 1 therapist conducted the telerehabilitation balance training at the therapist end to each facility for 1 month, separately. 1 volunteer or non‐medical person was assigned at the patient end for safety and assistance in telerehabilitation and conventional training. Control intervention: 2 post‐stroke participants attended the same session as the small therapy group. The therapist conducted conventional balance training programs following simple to complex principles. | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, post‐intervention Measures: Berg Balance Scale; Barthel Index | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer number generation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear, details not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Only one dropout and reason explained. Intention‐to‐treat analysis conducted |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes reported for all outcomes assessed in paper; however trial not registered and no protocol available |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from outpatients of the neurorehabilitation unit of a large metropolitan hospital in Spain Inclusion criteria: age ≥ 40 and ≤ 75 years; chronicity > 6 months; Brunel Balance Assessment (BBA): section 3, levels 7 to 12; Mini Mental State Examination score > 23; and Internet access in their homes Exclusion criteria: individuals with severe aphasia (Mississippi Aphasia Screening Test cut‐off score < 45); individuals with hemispatial neglect; and individuals with ataxia or any other cerebellar symptom Age, years: intervention group mean 55.47 (SD 9.63), control group man 55.6 (7.29) Gender: intervention group 67% men, control group 47% men Time post‐stroke: intervention group mean 334 (60 days), control group 317 (49 days) | |

| Interventions | All the participants underwent 20 x 45‐minute training sessions with the telerehabilitation system, conducted 3 times a week. The difficulty of the training was initially adjusted by PTA in an exploratory session. During the intervention, the difficulty of the task was adjusted either by the therapist or automatically by the system. The progress of all the participants was checked remotely once a week by PTA to detect possible issues and respond accordingly. In addition, PTB had a brief interview with participants of the experimental group each week to detect possible technical problems and to troubleshoot. On the remaining days (Tuesday and Thursday), both groups received conventional physical therapy in the clinic. The aim of the intervention was to improve balance. Telerehabilitation intervention: participants belonging to the experimental group trained in their homes Control intervention: participants belonging to the control group trained with the system in the clinic | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, post‐intervention (8 weeks), and follow‐up (12 weeks) Measures: cost, Berg Balance Scale, Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment‐Balance, Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment–Gait, Brunel Balance Assessment, system usability score, Intrinsic Motivation Inventory | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Held by external research in sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No withdrawals and all participants included in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No mention of clinical trial registration or protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from 5 acute care hospitals in Canada Inclusion criteria: all persons returning home directly from the acute care hospital after a first or recurrent stroke with any of the following criteria indicating a specific need for healthcare supervision postdischarge (lives alone, mobility problem requiring assistive device, physical assistance or supervision, mild cognitive deficit, dysphagia, incontinence, social service consultation during acute hospitalisation, or need for postdischarge medical management for diabetes, congestive heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, kidney disease, peripheral vascular disease) Exclusion criteria: people discharged to an inpatient rehabilitation facility or to long‐term care Age, years: telerehabilitation group = 70 (SD 14.5), control group = 72 (SD 12.95) Gender: telerehabilitation group 67% men, control group 55% men Time post‐stroke: telerehabilitation group 12 (SD 11.7 days), control group 13 (SD 15.7 days) | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: received case management (defined as a 'collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual's health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality cost‐effective outcomes'). Managed through home visits and telephone contacts for a period of 6 weeks. The nurse established contact with the GP and provided 24‐hour contact. Interventions included surveillance, information exchange, medication management, health system guidance, active listening, family support, teaching and risk identification. Control intervention: participant and family were instructed to make an appointment with their local GP. | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, post‐intervention, and 6‐month follow‐up Measures: reintegration to normal living index, Barthel Index, gait speed, Timed Up and Go test, SF‐36, EQ5D, Geriatric Depression Scale, health service utilisation | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Reported that 'sealed envelopes' were used |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessor |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Few instances of missing data. Balanced attrition across groups. ITT analyses conducted. Multiple imputation used for missing data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not able to access protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | None apparent |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from the community in Canada Inclusion criteria: a history of unilateral stroke resulting in a communication disorder, occurring at least 6 months in the past; availability of a communication partner to participate in the treatment programme; ability to travel to the treatment site if not at home, and ability to hear instructions and operate an iPad tablet to perform homework exercises Exclusion criteria: dementia or other neurological disorder Age, years: intervention group 66.8 (11.2), control group 62.9 (11.6) Gender: 59% men intervention group, 69% men control group Time post‐stroke: not reported (at least 6 months post‐stroke) | |

| Interventions | The study took place over 12 weeks for each participant, with an assessment in the first and last weeks and therapy during the intervening 10 weeks. Telerehabilitation intervention (Aphasia telerehab): remote therapy sessions were conducted via teleconferencing equipment and software. Participants possessing adequate equipment at home consulted the therapist using WebEx, a commercial teleconferencing program. Some clients visited the clinic to receive the telerehabilitation (provided in a separate room and contact with the therapist prohibited). During weeks 2‐11, the therapist conducted a 1‐hour weekly treatment session and TalkPath software was used for homework exercises. Control intervention (Aphasia in‐person): same therapy provided in‐person | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline and post‐intervention (12 weeks) Measures: Western Aphasia Battery Revised Part 1, Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test, Communication Confidence Rating Scale for Aphasia, Communication Effectiveness Index | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Assessments were conducted by a therapist not involved in the study but not clear if they were blind to allocation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Reporting of recruitment and withdrawals had limited detail including balance between groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Could not identify study protocol or trial registration |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups were separated by diagnosis; however it was not clear whether this was factored into the randomisation process. |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Study took place in Italy Inclusion criteria: mild to intermediate arm motor impairment due to ischaemic stroke in the area of the middle cerebral artery; without cognitive problems that could interfere with comprehension Exclusion criteria: failure to meet above criteria Age, years: telerehabilitation group = 53 (SD 15) years, control group = 65 (SD 11) years Gender: telerehabilitation group 40% men, control group 60% men Time post‐stroke: telerehabilitation group 10 months (SD 3), control group 13 months (SD 2) | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: the purpose of the intervention was to improve upper limb function using a virtual reality programme. Patient‐therapist interaction facilitated by a videoconferencing unit beside the telerehabilitation equipment. 1 computer was at the hospital and 1 at the participant's home Control intervention: virtual reality workstation with a 3D motion tracking system that recorded the participant's arm movements. The participant's movement was represented in the virtual environment. The therapist created a sequence of virtual tasks for the participant to complete with the affected arm. Participants could see their own trajectory and the ideal/desired trajectory. | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline and post‐intervention Measures: participant satisfaction questionnaire, Fugl‐Meyer Upper Extremity Scale | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Described as 'simple randomisation' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessor |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not able to access protocol |

| Other bias | High risk | Small sample size |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Study took place in Italy Inclusion criteria: single ischaemic stroke in the middle cerebral artery region with mild to intermediate arm motor impairment (Fugl‐Meyer Upper Extremity Scale score 30 to 55) Exclusion criteria: clinical evidence of cognitive impairment, apraxia (< 62 points on the 'De Renzi' test), neglect or language disturbance interfering with verbal comprehension (> 40 errors on the Token test) Age, years: telerehabilitation group mean = 66 (SD 8), control group mean = 64 (SD 8) years Gender: 58% men Timing post‐stroke: intervention group mean (SD) 15 (7) months, control group 12 (4) months | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: the virtual reality telerehabilitation programme used 1 computer workstation at the participant’s home and 1 at the rehabilitation hospital. The system used a 3D motion tracking system to record arm movements through a magnetic receiver into a virtual image. The participant moved a real object by following the trajectory of a virtual object displayed on the screen in accordance with the requested virtual task. 5 virtual tasks comprising simple arm movements were devised for training. | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, post‐intervention, and at 1 month Measures: Fugl‐Meyer Upper Extremity Scale, Abilhand Scale, modified Ashworth Scale | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Personal correspondence with study authors reported the use of a simple computer‐generated sequence. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Opaque sequentially numbered envelopes |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessor |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No missing data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No other outcomes collected |

| Other bias | Low risk | None apparent |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from 11 acute care hospitals located in urban and rural areas across 4 Canadian provinces Inclusion criteria: all adults who sustained a first mild stroke defined as a score > 8.5/11.5 on the Canadian Neurological Scale or a mRS between 0 and 2 on admission and who were discharged home within 3 weeks of the index event were invited. They needed to have telephone access, ability to understand basic instructions and express basic needs, and ability to communicate in English or French. Exclusion criteria: individuals with moderate or severe cognitive deficits (based on clinical judgement) and those who experienced another stroke before baseline measures were completed Age, years: intervention group mean 61.7 (SD 12.7), control group mean 63.2 (12.4) Gender: intervention group 65% men, control group 56% men Time post‐stroke: intervention group mean 6.5 days, control group 5.2 days | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: WE CALL participants received a multimodal (telephone, Internet, and paper) support intervention. Telephone interactions focused on any new or ongoing issues, as well as 6 key areas, including family functioning and individualised risk factors. Call frequency was weekly for the first 2 months, biweekly during the third month, and monthly for the past 3 months. Additional written information on stroke management was provided as needed (by regular mail, email, or Internet). Control intervention: YOU CALL participants were provided with the name and phone number of a trained healthcare professional who was not involved in providing the WE CALL intervention, whom they were free to contact should they feel the need. The health professional was instructed to answer the participant's queries on those topics initiated by the participant but not to probe further on other potential issues. | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, post‐intervention (6 months), 12 months Measures: unplanned use of health services (calendar), Quality of Life Index, EQ5D, Beck Depression Inventory, Assessment of Life Habits | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐managed stratified block randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes with external research managing randomisation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Large number of people were not able to be reached. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Protocol published and all outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from 2 acute hospitals in Germany Inclusion criteria: age ≥ 18 years, ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke for the first time (confirmed by imaging), main residency in the Federal States of Saxony‐Anhalt, Saxony, or Thuringia, and able to speak German Exclusion criteria: previous ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, alcoholism, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score > 25, and homelessness Age, years: intervention group mean 68.1 (SD 12.6), control group 68.4 (12.7) Gender: intervention group 34% men, control group 38% men Time post‐stroke: not reported but participants recruited from an acute hospital | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: in‐depth assessment and stroke support service provided by a nurse and physiotherapist. The stroke support service comprised stroke outreach support, educational sessions, and written patient information and was directed to both the patient and the next of kin. The stroke outreach support included home visits and telephone contacts and was individually tailored based on an agreement between the stroke support organiser and the patient and carer. The number of contacts between stroke support organiser and patient/carer was: 12.31% of contacts face‐to‐face and 61% via telephone; the remaining were written communications per email and normal post, or patient educational sessions. Control intervention: usual care | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: pre (prior to discharge from acute care), baseline (4 weeks after discharge prior to randomisation), and post (12 months after randomisation) Measures: Stroke Impact Scale (physical function domain), WHOQOL‐BREF, Geriatric Depression Scale, Symptom Checklist 90 Revised, health service use | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed and stapled envelopes |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Withdrawals across both groups but more in the usual care group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Registration as clinical trial performed in advance. All outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias noted |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Study took place in the USA Inclusion criteria: female caregiver providing care at home to husband after a stroke; either stroke survivor or caregiver scored 5 or greater on the PHQ‐9 (at least mild depression), neither stroke survivor nor caregiver were medically unstable or terminally ill and both were cognitively able to participate Exclusion criteria: failure to meet above criteria Age, years: telerehabilitation group mean = 59.9 (SD 8.2), control group mean = 59.1 (SD 13.6) Gender: 100% men Time since onset of stroke: details not reported | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: consisted of 5 components designed to support the caregiver and provide caregiver with knowledge, resources and skills to assist him or her in reducing 'personal distress' and providing optimal emotional care to the stroke survivor. The 5 components included:

Intervention took place over 11 weeks. Control group: had access to the Resource Room only | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, post‐intervention and at 1 month Measures: CES‐D, PHQ‐9, parts of the Mastery Scale, 10‐item self‐esteem scale, parts of the MOS Social Support Survey, ratings of treatment credibility, reported effort and perceived benefit | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated design |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed opaque envelopes |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessor |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | ITT analyses conducted. Few dropouts, all accounted for and balanced across groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Additional outcomes assessed that were not reported in the paper |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No other sources of bias identified |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from Bayreuth, Germany Inclusion criteria: > 12 months post‐stroke, aphasia, lesion on language dominant hemisphere Exclusion criteria: cognitive deficit, perceptual disorders, other motor deficits Age: mean 56 years, range 18 to 76 Gender: not reported Time post‐stroke: more than 12 months as per inclusion criteria but detail not reported | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation: therapy was delivered via a screen and the person and therapist were in separate rooms. 1 screen displayed the therapy material and the other displayed the people communicating. Control group: same form of therapy but delivered in‐person Dose: 3 times per week (60 minutes each) for 8 weeks. Assessment pre and post‐intervention lasting 5 to 8 hours | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, 8 weeks Measures: series of aphasia‐related measures and conversation analysis | |

| Notes | Article published in German and translated. Contacted the study author for more details but they did not respond | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Recruited from neurology departments of 2 major general hospitals in Guangzhou, China Inclusion criteria: age above 35 years, hospitalisation within 1 month from the onset of ischaemic stroke as diagnosed by neuroimaging (CT or MRI) based on Chinese Neuroscience Society criteria, previous independence in daily activities, score of 0 to 3 on the mRS at discharge and upon returning home following discharge, and ability to communicate and provide informed consent Exclusion criteria: a history of cardio‐embolic infarction, Wernicke's aphasia, cognitive impairment, a history of severe liver or kidney disease, and any known malignancy or other neurological diseases Age, years: intervention group mean (SD) 59.07 (12.36), control group 60.24 (12.57) Gender: intervention group 75% men, control group 68% men Time post‐stroke: not reported | |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: structured guideline‐based, goal‐setting programme for secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke. The telephone follow‐up sessions were conducted by stroke nurses and consisted of goal‐setting advice focused on selected areas. Participants set measurable behavioural goals and developed action plans. Participants received the same stroke education as the control group with an additional 3 telephone follow‐up calls at 1 week, and at 1 and 3 months after discharge, each lasting 15 to 20 minutes, to promote self‐management techniques and maintenance of behavioural improvements. Control intervention: usual care and education | |

| Outcomes | Timing of outcome assessment: baseline, 3 months, 6 months Measures: Chinese version of the Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile II; mRS score | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated sequence |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed opaque envelope |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinded outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Withdrawal in both groups and reporting of details unclear |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Registered with clinical trial registry and outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias noted |

ADL: activities of daily living

BBA: Brunel Balance Assessment

CES: Center for Epidemiologic Studies

CT: computerised tomography

EQ5D: Euroqol 5 Dimensions

ETNS: Electromyography triggered neuromuscular stimulation

FIM: Functional Independence Measure

fMRI: functional magnetic resonance imaging

FITT: Family Interventon Telephone Tracking

GP: general practitioner

HCAD: Home Care Activity Device

IHMD: In home messaging device

IQR: interquartile range

ITT: intention‐to‐treat

LTCF: Long term care facility

MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment

MOS: Medical Outcomes Study

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

mRS: modified Rankin Scale

NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale

PHQ‐9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9

PTA: physical therapist A

PTB: physical therapist B

RCT: randomised controlled trial

ROM: range of movement

SD: standard deviation

SE: standard error

SF‐12: Short Form 12

SF‐36: Short Form 36

U/E: Upper Extremity

WebEx: (communications platform)

WHOQOL‐BREF: World Health Organisation Quality of Life ‐ BREF tool

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Included participants with TIA | |

| Included participants with diagnoses other than stroke | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention did not match definition of telerehabilitation ‐ little remote contact once discharged home | |

| Included participants with diagnoses other than stroke and intervention did not meet our criteria | |

| Intervention did not involve telerehabilitation | |

| Included participants with TIA | |

| Did not meet definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Did not meet definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Mixed methods study underway in order to test feasibility of intervention and inform future RCT | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Not an RCT | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Not randomised ‐ pre/post design | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Included population with TIA or stroke | |

| Intervention did not meet our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Both groups received tele‐consultations; the difference between groups was the use of a robotic vs conventional home exercises | |

| Not an RCT | |

| Intervention did not meet our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention did not match definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention did not meet our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation | |

| Intervention group received more home visits than telerehabilitation consultations | |

| Intervention did not match our definition of telerehabilitation |

RCT: randomised controlled trial

TIA: transient ischaemic attack

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Adults with stroke (n = 15) |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: delivery of Cognitive Orientation to Occupational Performance approach (CO‐OP) via telerehabilitation. Dose of 16 hours over 10 weeks. CO‐OP involves having clients set meaningful everyday‐life goals and guiding them to discover contextually and personally relevant ways to improve performance on those goals. Control intervention: waiting‐list control group |

| Outcomes | Measures: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure |

| Notes | Abstract published in International Journal of Stroke (2017) detailing progress to date |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Adults with stroke, aged between 18 and 80 years, and living at home eligible to participate. Participants needed to be 2 to 72 months post‐stroke, and no longer receiving rehabilitation as in or outpatient. They should have moderate impairment of the affected upper extremity determined by range of motion. |

| Interventions | Each participant receives 12 x 45‐60‐minute sessions over 4 weeks while seated. Telerehabilitation intervention: Gertner Tele‐Motion‐Rehabilitation System treatment of comparable duration and intensity to those in the conventional treatment group with remote online monitoring by the therapist. Treatment feedback given in the form of knowledge of results (game scores) and knowledge of performance (feedback of compensatory movements made while using the upper extremity) to enhance motor learning. The software generates a report which will include the duration and type of exercises performed by the participant. The Gertner TMR system is implemented via Microsoft's Kinect 3‐D camera‐based gesture recognition technology. Using the patient's natural hand and body movements to control all activity within customised computer games. The system runs off a standard desktop computer and is displayed on a large television screen. Control intervention: the control group receives self‐training exercises that are based on conventional therapy using principles of motor control and includes training of upper extremity movements in order to achieve better use of the affected arm in ADL. |

| Outcomes | Shoulder and elbow range of motion (measured with goniometer), Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory, Motor Activity Log, Functional Reach Test, Lawton's IADL, Fugl‐Meyer Motor Assessment, Visual Analogue Scale, Functional Independence Measure, Stroke Impact Scale |

| Notes |

| Methods | Randomised controlled (crossover) trial |

| Participants | Adults after stroke |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: web‐based rehabilitation programme 'Move it to Improve it' (Mitii) Control intervention: waiting‐list control |

| Outcomes | Outcomes assessed at baseline, 16 and 32 weeks and included: Modified Rankin Sacle, Barthel Index, physical assessment (NIHSS, motor assessment scale), cognitive tests and general well‐being (WHO‐5) |

| Notes | Abstract published but further details of the trial not yet available |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Stroke survivors discharged from rehabilitation |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: education, home‐based exercise programme and telephone contacts weekly for 12 weeks Control intervention: education and surveillance |

| Outcomes | Outcomes assessed at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks Outcomes assessed: visual analogue quality of life scale, step activity profiles and self‐efficacy for falls |

| Notes |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: stroke survivors more than 1 year after stroke with the ability to open fingers on affected side, raise wrist, transfer and stand independently for 2 minutes |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation intervention: constraint‐induced therapy (automated, remotely administered) Control intervention: constraint‐induced therapy |

| Outcomes | Outcomes assessed at 2 weeks, 6 months, 12 months Outcomes assessed: Motor Activity Log, Wolf Motor Function Test |

| Notes |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People with stroke and their caregiver |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation: CARE4STROKE caregiver‐mediated programme with ehealth support Control intervention: usual care |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: mobility domain of the Stroke Impact Scale |

| Notes |

ADL: activities of daily living

CO‐OP: Cognitive Orientation to Occupational Performance

IADL: Instrumental activities of daily living

Mitii: Move it to Improve it

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

RCT: randomised controlled trial

WHO‐5: World Health Organisation 5 Well Being Index

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | A telehealth transfer package to improve post‐stroke rehabilitation outcomes |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (RCT) |

| Participants | People after stroke receiving an outpatient or day patient rehabilitation programme will be recruited |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation group: individual (1‐on‐1) face‐to‐face sessions 1 x per week after the patient's formal therapy visit and via individual (1‐on‐1) telehealth sessions 4 x per week. The intervention package includes: a behavioural contract where the participant and applicant will decide which activities the participant will complete with their more‐affected hand. This will be reviewed each day by the therapist and participant during their session and amended accordingly; a daily motor activity log; a daily activity diary, a daily schedule of home practice prescribed by the treating therapists and a list of optional motor‐function specific supplementary activities the participant can complete at their leisure. The telehealth component will be delivered via Skype on the patient's usual household computer. Control group: the control group will receive their usual 8‐week outpatient occupational programme. They will not receive the additional telehealth transfer package. |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Fugl Meyer Assessment |

| Starting date | 2016 |

| Contact information | A/Prof Steven Faux: [email protected] |

| Notes | ACTRN12617000168358 |

| Trial name or title | Inspiring Virtual Enabled Resources following Vascular Events (iVERVE) |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People after stroke recruited from the Australian Stroke Survivor Clinical Registry |

| Interventions | Structured and comprehensive patient‐centred goal‐setting conducted over the phone in survivors of stroke with SMS support messages |

| Outcomes | Goal attainment |

| Starting date | 2017 |

| Contact information | Professor Dominic Cadilhac: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Home‐based physical activity incentive and education programme in subacute phase of stroke recovery (Ticaa’dom) |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People in the subacute phase after stroke |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation: home‐based physical activity incentive and education programme (Ticaa’dom). The intervention group will follow the programme over 6 months: their physical activity will be monitored with an accelerometer during the day at home while they record their subjective perception of physical activity on a chart; they will observe a weekly telephone call and a home visit every 3 weeks. Control: usual care |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: 6‐Minute Walk Test. Secondary outcomes will include measurements of lower limb strength, independence level, body composition, cardiac analysis, fatigue and depression state. |

| Starting date | 2013 |

| Contact information | David Chaparro: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Effectiveness and neural mechanisms of home‐based telerehabilitation in patients with stroke based on fMRI and DTI |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People after stroke |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation vs conventional rehabilitation |

| Outcomes | Fugl Meyer Assessment |

| Starting date | Unknown |

| Contact information | Chuancheng Ren: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Effectiveness, safety and cost efficiency of telerehabilitation for stroke patients in hospital and home |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People after stroke with unilateral motor deficits |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation compared with other models of service delivery (further detail not reported) |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Fugl Meyer outcome assessment |

| Starting date | 2015 |

| Contact information | Yun Qu: [email protected] |

| Notes | Listed on Chinese Clinical Trial Registry |

| Trial name or title | VIdeo Game Rehabilitation for OUtpatient Stroke (VIGoROUS) |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People with chronic hemiparesis following stroke |

| Interventions | The researchers will test different forms of constraint‐induced (CI) movement therapy: (1) traditional clinic‐based CI therapy, (2) therapist‐as‐consultant video game CI therapy, (3) therapist‐as‐consultant video game CI therapy with additional therapist contact via telerehabilitation/video consultation, and (4) standard upper extremity rehabilitation |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Wolf Motor Function Test |

| Starting date | Unknown |

| Contact information | A/Prof Lynne Gauthier: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Singapore Tele‐technology Aided Rehabilitation in Stroke (STARS) trial |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People with recent stroke |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation: exercise 5 days‐a‐week using an iPad‐based system that allows recording of daily exercise with video and sensor data and weekly videoconferencing with teletherapists after data review Control: usual care |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Jette Late Life Functional and Disability Instrument |

| Starting date | 2015 |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Development and pilot evaluation of a Web‐supported programme of constraint‐induced therapy following stroke (LifeCIT) |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Stroke patients |

| Interventions | Intervention group: participants will be asked to aim to wear the mitt for 9 hours a day for 5 days/week, including 4 to 6 hours of structured activities per day: 2 x 30 to 60‐minute sessions of Web‐based activities and 3 to 4 hours of practicing everyday activities Control group: usual care |

| Outcomes | Motor Activity Log, Wolf Motor Function Test, Fugl‐Meyer Upper Extremity Scale, Stroke Impact Scale, Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, EQ5D, service utilisation |

| Starting date | May 2011 |

| Contact information | Claire Meagher: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | TeleRehab for stroke patients using mobile technology |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants |

|

| Interventions | The study SLP will instruct the patient to use the iPad apps as an intervention for at least 1 hour per day, until they are admitted to outpatient SLP services or for a maximum of 8 weeks, whichever comes first. Throughout the telemedicine treatment phase, participants' progress will be monitored remotely by a study SLP through Apps/Skype/Facetime/Telephone consultation on a weekly basis Control group: usual care |

| Outcomes | Feasibility |

| Starting date | 2015 |

| Contact information | Karen Mallet: [email protected] |

| Notes | Completed recruitment and currently writing up |

| Trial name or title | Translating intensive arm rehabilitation in stroke to a telerehabilitation format (TeleBATRAC) |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People > 6 months after stroke with moderate to severe arm impairment (Fugl Meyer score 19 to 50) |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation: home‐based training will consist of 45 minutes of high‐intensity bilateral reaching and rest periods using the Bilateral Arm Training with Rhythmic Auditory Cuing (BATRAC device) followed by 15 minutes of video‐guided transition to task training. These videos will be linked from the Veterans Affairs MyHealtheVet site to study specific Youtube videos of the study therapist demonstrating the exercise. Asynchronous communication between the therapist and participant will be completed using the MyHealtheVet secure messaging system Control group: clinic‐based approach of same therapy approach |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Wolf Motor Function Test |

| Starting date | 2016 |

| Contact information | Susan Conroy: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | A trial investigating telerehabilitation as an add‐on to face‐to‐face speech and language therapy in post‐stroke aphasia |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People after stroke with aphasia |

| Interventions | High teleSLT frequency intervention in which the experimental group trains for 96 minutes per day using a tablet computer delivering speech and language exercises Low teleSLT frequency intervention in which the control group trains for 24 minutes per day |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Amsterdam‐Nijmegen Everyday Language Test |

| Starting date | 2017 |

| Contact information | Professor René Müri: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Efficacy of an interactive web‐based home therapy program after stroke |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Patients after stroke who are discharged from outpatient rehabilitation and have impaired upper limb function |

| Interventions | Web‐based home exercise programme vs standard home exercise programme |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Fugl Meyer Upper Extremity |

| Starting date | 2018 |

| Contact information | A/Professor Sandy McCombe Waller |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Game‐based home exercise programs in chronic stroke: a feasibility study |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People within 6 months of having a stroke |

| Interventions | Virtual reality Mystic Isle game vs standard home exercise programme |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure |

| Starting date | 2018 |

| Contact information | A/Professor Rachel Proffitt |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Optimising a home‐based virtual reality exercise programme for chronic stroke patients: a telerehabilitation approach |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People with stroke who are no longer receiving rehabilitation services and have upper limb impairment |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation (8‐week home‐based virtual reality and telerehabilitation system) versus usual care |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Fugl Meyer‐upper extremity |

| Starting date | 2018 |

| Contact information | A/Professor Dahlia Kairy |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Pharmacist telephone interventions improve adherence to stroke preventative medications and reduce stroke risk factors: an RCT |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Stroke patients |

| Interventions | Intervention group: received telephone follow‐up calls at 3 months and 6 months from time of randomisation Telephone follow‐up call included evaluation of medication adherence based on pharmacy refill history, as well as continuing stroke education and reassessment of stroke prevention goals with the participant. Recommendations for medication therapy and relevant clinical studies or laboratories were communicated to the primary care provider and/or stroke provider when appropriate. Control group: usual care |

| Outcomes | Adherence to medication, achievement of stroke prevention goals |

| Starting date | Unknown |

| Contact information | Unavailable |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Telerehabilitation for aphasia |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People with aphasia post‐stroke |

| Interventions | Telerehabilitation: standard speech and language therapy and additional 5 hours of telerehabilitation per week over 4 weeks through video conference focusing on spoken language and word naming Usual care: standard speech and language therapy |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: naming ability 3 months after intervention |

| Starting date | Unclear |

| Contact information | Hege Prag Øra: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Evaluating an extended rehabilitation service for stroke patients: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Participants are adults who have experienced a new stroke (and carer if appropriate), discharged from hospital under the care of an early supported discharge (ESD) team |

| Interventions | The intervention group receives an extended stroke rehabilitation service provided for 18 months following completion of ESD. |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome is extended activities of daily living (Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Scale) at 24 months post‐randomisation. Secondary outcomes (at 12 and 24 months post‐randomisation) are health status, quality of life, mood and experience of services for patients, and quality of life, experience of services, and carer stress for carers. Resource use and adverse events are also collected. |

| Starting date | |

| Contact information | Helen Rodgers: [email protected] |

| Notes | ISRCTN45203373 |

| Trial name or title | A telehealth intervention to promote healthy lifestyles after stroke: the Stroke Coach protocol |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Participants will be recruited from acute, rehabilitation, and outpatient stroke units. Individuals will be included for study if they: are within 1 year following a confirmed stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic, diagnosis either by computerised tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging); 50 years of age; have a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) 9 score varying from 1 to 4; live in the community and have phone access; and are able to communicate in English |

| Interventions | The Stroke Coach is a patient‐centred telehealth self management intervention to improve lifestyle behaviours after stroke that was developed using an Intervention Mapping process. |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Lifestyle Profile II questionnaire |

| Starting date | Not known |

| Contact information | Janice Eng: [email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Telerehabilitation to improve outcomes for people with stroke (ACTIV) |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People will be eligible for inclusion if they have had a first ever hemispheric stroke of haemorrhagic or ischaemic origin; are over the age of 20 years; have been discharged from inpatient, outpatient and community physiotherapy services to live in their own home (participants involved in other forms of therapy such as occupational therapy, Tai Chi, or community exercise programmes will not be excluded); have medical clearance from their General Practitioner to participate in a low to moderate‐level activity programme; score at least 3 on a telephone cognitive screening questionnaire; have a limitation in physical function of leg, arm, or both |

| Interventions | The Augmented Community Telerehabilitation Intervention (ACTIV) is a 6‐month standardised programme delivered in the participant’s home, focusing on two functional categories: ‘staying upright’ and ‘using your arm’. |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome measure is the physical function subcomponent of the SIS 3.0. |

| Starting date | Unclear |

| Contact information | Nicola Saywell: [email protected] |

| Notes | Note that abstract was presented at the 26th European Stroke Conference in Germany (2017) detailing recruitment of 95 participants and preliminary analysis but full results are not yet available. |