Relaxation techniques for pain management in labour

Résumé scientifique

Contexte

De nombreuses femmes souhaiteraient éviter le recours à des méthodes pharmacologiques ou invasives de gestion de la douleur pendant l’accouchement, ce qui permet ainsi de promouvoir la popularité de méthodes complémentaires de gestion de la douleur. Cette revue a examiné les preuves actuellement disponibles corroborant l’utilisation de thérapies de relaxation pour la gestion de la douleur pendant l’accouchement.

Objectifs

Examiner les effets des méthodes de relaxation pour la gestion de la douleur pendant l’accouchement au niveau de la morbidité maternelle et périnatale.

Stratégie de recherche documentaire

Nous avons effectué des recherches dans le registre des essais du groupe Cochrane sur la grossesse et l’accouchement (30 novembre 2010), le registre des essais du groupe Cochrane sur l’évaluation des biais (novembre 2011), le registre Cochrane des essais contrôlés (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2010, numéro 4), MEDLINE (1966 au 30 novembre 2010), CINAHL (1980 au 30 novembre 2010), le registre des essais cliniques australiens et néo‐zélandais (30 novembre 2010), le registre des essais cliniques chinois (30 novembre 2010), le registre des essais cliniques (30 novembre 2010), ClinicalTrials.gov, (30 novembre 2010), le registre ISRCTN (30 novembre 2010), le National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) (30 novembre 2010) et le système d’enregistrement international des essais cliniques de l’Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS) (WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) (30 novembre 2010)..

Critères de sélection

Des essais contrôlés randomisés comparant des méthodes de relaxation à des soins standard, l’absence de traitement, d’autres formes non pharmacologiques de gestion de la douleur pendant l’accouchement ou un placebo.

Recueil et analyse des données

Trois auteurs de la revue ont évalué les essais à inclure et extrait des données de façon indépendante. L’exactitude des données a été vérifiée. Deux auteurs de la revue ont évalué la qualité des essais de façon indépendante. Nous avons essayé de contacter les auteurs des études pour obtenir des informations supplémentaires.

Résultats principaux

Nous avons inclus 11 études (1 374 femmes) dans la revue. La relaxation était associée à une baisse d’intensité de la douleur au cours de la phase latente (différence moyenne (DM) ‐ 1,25, intervalle de confiance (IC) à 95 % ‐ 1,97 à ‐ 0.53, un essai, 40 femmes) et de la phase active de l’accouchement (DM ‐ 2,48, IC à 95 % ‐ 3,13 à 0,83, deux essais, 74 femmes). Des preuves révélaient une amélioration des résultats grâce aux instructions de relaxation avec une hausse de la satisfaction en termes de soulagement de la douleur (risque relatif (RR) 8,00, IC à 95 % 1,10 à 58,19, un essai, 40 femmes) et une baisse des accouchements par voie basse assistés (RR 0,07, IC à 95 % 0,01 à 0,50, deux essais, 86 femmes). Le yoga était associé à une diminution de la douleur (différence moyenne (DM) ‐ 6,12, IC à 95 % ‐ 11,77 à ‐ 0,47), un essai, 66 femmes), une hausse de la satisfaction en termes de soulagement de la douleur (DM 7,88, IC à 95 % 1,51 à 14,25, un essai, 66 femmes), de la satisfaction de l’expérience d’accouchement (DM) 6,34, IC à 95 % 0,26 à 12,42, un essai, 66 femmes) et à une diminution de la durée de l’accouchement comparée à des soins standard (DM ‐ 139,91, IC à 95 % ‐ 252,50 à ‐ 27,32, un essai, 66 femmes) et à la position couchée sur le dos (DM ‐ 191,34, IC à 95 % ‐ 243,72 à ‐ 138,96, un essai, 83 femmes). Les essais évaluant l’analgésie obtenue par l’écoute de musique ou de sons ne révélait aucune différence entre les groupes au niveau de l’intensité de la douleur dans les résultats principaux, la satisfaction avec soulagement de la douleur et l’accouchement par césarienne. Les risques de biais étaient approximatifs pour la majorité des essais.

Conclusions des auteurs

La relaxation et le yoga peuvent jouer un rôle dans la diminution de la douleur, la hausse de la satisfaction avec soulagement de la douleur et la baisse des taux d’accouchements par voie basse assistés. Les preuves fournies étaient insuffisantes pour confirmer le rôle de l’analgésie obtenue par l’écoute de musique ou de sons. Toutefois, d’autres recherches doivent être effectuées

PICO

Résumé simplifié

Techniques de relaxation pour la gestion de la douleur pendant l’accouchement

La douleur ressentie lors de l’accouchement peut être intense et empirer avec l’apparition de tensions dans l’organisme, l’anxiété et la peur. Beaucoup de femmes souhaiteraient accoucher en évitant la prise de médicaments ou sans avoir recours à des méthodes invasives comme la péridurale et se tourner vers des thérapies complémentaires permettant d’atténuer leur perception de la douleur et améliorer sa gestion. De nombreuses thérapies complémentaires sont testées, notamment l’acupuncture, les techniques mettant en relation l’esprit et le corps, les massages, la réflexologie, les plantes médicinales ou l’homéopathie, l’hypnose, la musique et l’aromathérapie. Les interventions mettant en rapport le corps et l’esprit, comme la relaxation, la méditation, la visualisation et la respiration, sont généralement appliquées à l’accouchement et sont largement accessibles aux femmes grâce à l’enseignement de ces techniques lors de cours prénataux. Le yoga, la méditation et l’hypnose peuvent ne pas être facilement accessibles aux femmes, mais combinées les unes aux autres, ces techniques peuvent avoir un effet apaisant et aider les femmes à gérer leur douleur et servir de distraction de la douleur et de la tension. Cette revue de onze essais contrôlés randomisés, composée de données obtenues auprès de 1 374 femmes, a révélé que les techniques de relaxation et le yoga peuvent aider à gérer la douleur ressentie pendant l’accouchement. Toutefois, ces essais variaient au niveau des méthodes d’applications de ces techniques. Un nombre limité ou unique d’essais signalaient une baisse d’intensité de la douleur, une hausse de la satisfaction en termes de soulagement de la douleur, une hausse de la satisfaction concernant l’accouchement et une baisse des taux d’accouchements par voie basse assistés. Des recherches supplémentaires doivent être effectuées.

Authors' conclusions

Background

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of pain management for women in labour (Jones 2011b), and share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a).

Description of the condition

Labour presents a physiological and psychological challenge for women. As labour becomes more imminent this can be a time of conflicting emotions; fear and apprehension can be coupled with excitement and happiness. Pain associated with labour has been described as one of the most intense forms of pain that can be experienced (Melzack 1984), although some women do not experience intense pain during labour. Labour consists of three stages, relating to dilation of the cervix, delivery of the baby and delivery of the placenta. The first stage of labour consists of three phases. The latent phase consists of mild contractions which may be regular or irregular. The active phase of labour consists of stronger, painful contractions that tend to occur around three or four minutes apart and last up to a minute, and during this time the cervix dilates to around 7 cm. The transition phase consists of intense, painful and frequent contractions which lead the cervix to fully dilate. The second stage of labour commences from full cervical dilation to the delivery of the baby. The pain experienced by women in labour is caused by uterine contractions, the dilatation of the cervix and, in the late first stage and second stage, by stretching of the vagina and pelvic floor to accommodate the baby. There are several philosophies of pain control, which involve using strategies to break what has been described as the fear‐tension‐pain cycle (Dick‐Read 2004; Dowswell 2009). Grantly Dick‐Read, an advocate of 'natural childbirth', suggested that fear and anxiety can produce muscle tension, resulting in an increased perception of pain. The neuromatrix theory of pain understands the influence of many factors including past experience and memory (Melzack 2001). In labour the theory of pain incorporates elements of the gate control theory, but also past experiences, cultural factors, emotional state, cognitive input, stress regulation and immune systems, as well as immediate sensory input (Trout 2004). However, the complete removal of pain does not necessarily mean a more satisfying birth experience for women (Morgan 1982). Effective and satisfactory pain management needs to be individualised for each woman, and may be influenced by two paradigms, working with pain, or pain relief (Leap 2010). The working with pain paradigm includes the belief that there are long term benefits to promoting normal birth, and that pain plays an important role in this process. The working with pain approach offers support and encouragement to women, advocates the use of immersion in water, comfortable positions and self‐help techniques to cope with normal labour pain. The pain relief paradigm is characterised by the belief that no woman need suffer pain in labour and women are offered a variety of pharmacological pain relief.

Description of the intervention

The use of complementary and alternative therapies (CM) has become popular with consumers worldwide. Studies suggest that between 36% and 62% of adults in industrialised nations use some form of CM to prevent or treat health‐related problems (Barnes 2004). Complementary therapies are more commonly used by women of reproductive age, with almost half (49%) reporting use (Eisenberg 1998). Many women would like to avoid pharmacological or invasive methods of pain relief in labour and this may contribute towards the popularity of complementary methods of pain management (Bennett 1999). It is possible that a significant proportion of women are using these therapies during pregnancy. A recent review of 14 studies with large sample sizes (n ≧ 200) on the use of CM in pregnancy identified a prevalence rate ranging from 1% to 87% (with nine falling between 20% and 60%) (Adams 2009). The review identified use of various complementary therapies including acupuncture and acupressure, aromatherapy, massage, yoga, homeopathy and chiropractic care. The review also showed many pregnant women had used more than one complementary product or service (Adams 2009).

The Complementary Medicine Field of the Cochrane Collaboration defines complementary medicine as 'practices and ideas which are outside the domain of conventional medicine in several countries', which are defined by its users as 'preventing or treating illness, or promoting health and wellbeing' (Manheimer 2008). This definition is deliberately broad, as therapies considered complementary practices in one country or culture may be conventional in another. Many therapies and practices are included within the scope of the Complementary Medicine Field. These include treatments people can administer themselves (e.g. botanicals, nutritional supplements, health food, meditation, magnetic therapy), treatments providers administer (e.g. acupuncture, massage, reflexology, chiropractic and osteopathic manipulations), and treatments people can administer under the periodic supervision of a provider (e.g. yoga, biofeedback, Tai Chi, homoeopathy, Alexander therapy, Ayurveda).

The most commonly cited complementary practices associated with providing pain management in labour can be categorised into mind‐body interventions (e.g. yoga, hypnosis, relaxation therapies), alternative medical practice (e.g. homoeopathy, traditional Chinese medicine), manual healing methods (e.g. massage, reflexology), pharmacologic and biological treatments, bioelectromagnetic applications (e.g. magnets) and herbal medicines. Mind‐body interventions are diverse, and include relaxation, meditation, visualisation and breathing are commonly used for labour, and can be widely accessible to women through teaching of these techniques during antenatal classes. Yoga, meditation and hypnosis may not be so accessible to women but together these techniques may have a calming effect and provide a distraction from pain and tension (Vickers 1999).

Relaxation techniques included in this review include guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, breathing techniques, yoga and meditation. Hypnosis is examined in a separate review. Guided imagery is a technique that uses the mind’s own capacity to affect a person’s state physically, emotionally or spiritually, and Imagery is using one's imagination as therapeutic tool (McCaffery 1979). Imagery is a learned technique whereby the patient recalls an enjoyable and relaxing experience, which is used to decrease the intensity of pain or to substitute an unpleasant sensation. The main purpose of this technique is to evoke an altered state where a person can stimulate and utilise significant bodily functions and products that are not usually available to us (Schorn 2009). Guided imagery for labour and childbirth aims to effect labour by reducing stress. Progressive muscle relaxation was originally designed by Jacobson to guide people through successive tensing and relaxation of the body muscle groups from toe to head to achieve overall body relaxation( Jacobson 1938). Women are encouraged to focus on sensations associated with the release of muscle tension and feelings of comfort. Imagery may involve encouraging participants to scan their bodies to identify areas of pain and to imagine replacing pain with comforting sensations such as heat or cold. This process is easy to learn and teach, safe, non‐threatening and non‐competitive. Breathing techniques referred to as psychoprophylaxis emphasise relaxation as a conditioned response to labour contractions coupled with a variety of patterned breathing techniques designed to improve oxygenation and interfere with the transmission of pain signals from the uterus to the brain (Velvovsky 1960). Yoga is a mind‐body practice, and various styles of yoga can be used for health purposes by combining physical postures, breathing techniques and meditation or relaxation. A commonly practised form of yoga includes Hatha yoga. This includes breath awareness and internal centring to remove external concerns, achieve focus and become sensitive towards internal feelings; as well as relaxation and meditation to further enhance ridding the body of ‘toxins’ and enable release from mental and emotional blockages. Accompanying this are bodily postures that address mind‐body‐breath coordination, strength, flexibility and balance (Fisher 2004).

How the intervention might work

Relaxation and guided imagery are two coping strategies that may reduce pain by interrupting the transmission of pain signals, limiting the capacity to pay attention to pain, stimulating the release of endorphins, or by helping patients diminish pain‐exacerbating thoughts (Sharp 2001; Villemure 2002). It is not fully known what changes occur in the body in response to yoga.

Why it is important to do this review

There is interest by women to use additional forms of care to assist with their pain management in labour. It is important to examine the efficacy, effectiveness and safety of under‐evaluated forms of treatment to enable women, health providers and policy makers to make informed decisions about care. A number of clinical trials have been performed to study the effect of relaxation techniques for pain in labour, although it remains uncertain whether the existing evidence is rigorous enough to reach a definitive conclusion.

Objectives

To examine the effects of relaxation techniques for pain management in labour on maternal and perinatal morbidity.

This review examines the hypotheses that the use of relaxation techniques are:

-

an effective means of pain management in labour as measured by decreases in women's rating of labour pain: a reduced need for pharmacological intervention;

-

improved maternal satisfaction or maternal emotional experience; and

-

relaxation methods have no adverse effects on the mother (duration of labour, mode of delivery) or baby.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) only. (We will not include results from quasi RCTs in the analyses but we may discuss them in the text if little other evidence is available.)

Types of participants

Women in labour. (This will include women in high‐risk groups, e.g. preterm labour or following induction of labour. We will use subgroup analysis to look for any possible differences in the effect of interventions in these groups.)

Types of interventions

These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of interventions for pain management in labour (in preparation), and share a generic protocol (in preparation). To avoid duplication, the different methods of pain management have been listed in a specific order, from one to 15. Individual reviews focusing on particular interventions include comparisons with only the intervention above it on the list. We will add methods of pain management identified in the future to the end of the list. The current list is as follows.

-

Placebo/no treatment

-

Hypnosis (Madden 2011)

-

Biofeedback (Barragán 2011)

-

Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection (Derry 2011)

-

Immersion in water (Cluett 2009)

-

Aromatherapy (Smith 2011b)

-

Relaxation techniques (yoga, music, audio) (this review)

-

Acupuncture or acupressure (Smith 2011a)

-

Manual methods (massage, reflexology) (Smith 2011c)

-

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (Dowswell 2009)

-

Inhaled analgesia (Klomp 2011)

-

Opioid drugs (Ullman 2010)

-

Non‐opioid drugs (Othman 2011)

-

Local anaesthetic nerve blocks (Novikova 2011)

-

Epidural (including combined spinal‐epidural) (Anim‐Somuah 2005; Simmons 2007)

Accordingly, this review will include comparisons of one form of relaxation technique compared with any other type of relaxation technique, or relaxation compared with 1. placebo/no treatment/usual care; 2. hypnosis; 3. biofeedback; 4. intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection; 5. immersion in water; or 6. aromatherapy.

Types of outcome measures

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of interventions for pain management in labour, and share a generic protocol. The following list of primary outcomes are the ones which are common to all the reviews.

Primary outcomes

Effects of interventions

-

Pain intensity (as defined by trialists)

-

Satisfaction with pain relief (as defined by trialists)

-

Sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists)

-

Satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists)

Safety of interventions

-

Effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction

-

Breastfeeding (at specified time points)

-

Assisted vaginal delivery

-

Caesarean section

-

Side effects (for mother and baby; review specific)

-

Admission to special care nursery or neonatal intensive care (as defined by trialists)

-

Low Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (less than seven)

-

Poor infant outcomes at long‐term follow up (as defined by trialists)

Other outcomes

-

Cost (as defined by trialists)

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Use of pharmacological pain relief; length of labour; spontaneous vaginal delivery; need for augmentation with oxytocin; perineal trauma (defined as episiotomy and incidence of second‐ or third‐degree tear); maternal blood loss (postpartum haemorrhage defined as greater than 500 ml); anxiety.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (30 November 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

-

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

-

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

-

weekly searches of EMBASE;

-

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

-

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We searched the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field's Trials Register using the terms (labor OR labour).

In addition, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2010, Issue 4) (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (1966 to 30 November 2010) (Appendix 2), and CINAHL (1980 to 30 November 2010) (Appendix 3).

We also searched the following for ongoing or unpublished trials: the Australian and New Zealand Trials Registry (30 November 2010); the Chinese Clinical Trial Register (30 November 2010); Current Controlled Trials (30 November 2010); ClinicalTrials.gov (30 November 2010); the ISRCTN Register; (30 November 2010); National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) (30 November 2010); and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). (30 November 2010). See:Appendix 4 for search terms used in these sources.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

We used the following methods when assessing reports identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Three review authors (C Smith (CS), CT Collins (CTC) and K Levett (KL)) screened the titles and abstracts of articles found in the search, and discarded trials that were clearly not eligible. Two out of the three review authors (CS, CTC, KL) undertook trial selection.

CS, KL and CTC independently assessed whether the trials met the inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved by discussion with the fourth author (C Crowther). When articles contained insufficient information to make a decision about eligibility, CS attempted to contact authors of the original reports to obtain further details.

Data extraction and management

Following an assessment for inclusion, CS, KL or CTC independently extracted data using the form designed by the Review Group for this purpose. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a fourth person. For each included trial, we collected information regarding the location of the trial, methods of the trial (as per assessment of risk of bias), the participants (age range, eligibility criteria), the nature of the interventions and data relating to the outcomes specified above. We collected information on reported benefits and adverse effects. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

The tool consists of six items. There are three potential responses: high risk, low risk or unclear risk. We also made a judgement of ‘unclear’ if what happened in the study was known but the risk of bias was unknown; or if an entry was not relevant to the study at hand (particularly for assessing blinding and incomplete outcome data, or when the outcome being assessed by the entry has not been measured in the study).

We assessed the following characteristics: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (or masking), incomplete data assessment, selective outcome reporting, other sources of bias, described below. We generated a 'risk of bias assessment' table for each study.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We will assessed the method as:

-

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

-

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

-

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

-

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

-

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

-

unclear risk of bias.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We judged that blinding of participants and caregiver would not be possible due to the type of intervention being assessed. For this reason we assessed whether the lack of blinding was likely to have introduced bias in the measure of outcomes of interest. Blinding was assessed for primary outcomes as:

-

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses undertaken (we set a threshold of missing data less than 20%). We assessed methods as:

-

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

-

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

-

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

-

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

-

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

-

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias, for example was there a potential source of bias related to the specific study design? Was the trial stopped early due to some data‐dependent process? Was there extreme baseline imbalance? Has the study been claimed to be fraudulent?

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

-

low risk of other bias;

-

high risk of other bias;

-

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. We aimed to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

We expressed continuous data as mean differences with 95% CIs, or as standardised mean differences if outcomes were conceptually the same in the different trials but measured in different ways.

Unit of analysis issues

We included cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials, and adjusted their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we used ICCs from other sources, we would report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identified both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we planned to synthesise the relevant information. We considered it reasonable to combine the results from both if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely. We would also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We aimed to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and analysed all participants in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing. We excluded trials with greater than 20% missing data from the analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if T² was greater than zero and either I² was greater than 50% or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there were 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we planned to investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We would assess funnel plot asymmetry visually, and would use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes we would use the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we would use the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If asymmetry was detected in any of these tests or was suggested by a visual assessment, we proposed to perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. We treated the random‐effects summary as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful we have not combined trials.

If we used the random‐effects analyses, we have presented the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We investigated substantial heterogeneity was investigated using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, a random‐effects analysis was undertaken.

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

-

Spontaneous labour versus induced labour.

-

Primiparous versus multiparous.

-

Term versus preterm birth.

-

Continuous support in labour versus no continuous support.

We judged subgroup differences by the results of interaction tests produced by RevMan.

Sensitivity analysis

Where subgroup analysis failed to explain the heterogeneity, we planned to analyse the data using the random‐effects model. A priori, we planned to perform sensitivity analyses on results to look at the possible contribution of: (1) differences in methodological quality, with trials of high quality (low risk of bias) compared to all trials; and (2) publication bias by country. If publication bias was present we planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis excluding trials from countries where there was a greater publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The original review included a range of complementary therapies (Smith 2006). This updated review includes trials of therapies involving relaxation techniques. We included 11 studies (1374 women), and excluded 12 studies. We included eight new studies (Almeida 2005; Bagharpoosh 2006; Bergstrom 2009; Chuntharapat 2008; Gatelli 2000; Liu 2010; Phumdoung 2007; Yildirim 2004). Two studies await further assessment (Escott 2005; Salem 2004) and one trial is ongoing (Esterkin 2010).

SeeCharacteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification, Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Included studies

Study design

Seven trials were parallel designs, one trial used a factorial design (Phumdoung 2007) and one trial used a cluster randomisation (Bergstrom 2009). Nine studies had two groups (one trial had four groups (Gatelli 2000), and one trial had five groups (Phumdoung 2007). Control groups varied, seven trials used usual care, three trials used psychoprophylaxis (Dolcetta 1979; Durham 1986; Gatelli 2000), one trial used a different dose of audio‐analgesia (Moore 1965) and one trial used different forms of postural management (Phumdoung 2007).

Sample size

Sample size ranged from 25 (Moore 1965) to 1087 (Bergstrom 2009).

Study location and source of women

Two studies were undertaken in Italy (Dolcetta 1979; Gatelli 2000) and Thailand (Chuntharapat 2008; Phumdoung 2007) and one study each from Brazil (Almeida 2005), Iran (Bagharpoosh 2006), Sweden (Bergstrom 2009), Taiwan (Liu 2010), Turkey (Yildirim 2004), the United Kingdon (Moore 1965) and the United States (Durham 1986). Six studies recruited women during their antenatal care (Almeida 2005; Bergstrom 2009; Chuntharapat 2008; Dolcetta 1979; Durham 1986, Gatelli 2000), and five trials recruited women in the labour ward (Bagharpoosh 2006; Liu 2010; Moore 1965; Phumdoung 2007; Yildirim 2004).

Participants

Studies included primiparous and multiparous women.

Types of interventions

The interventions were grouped into relaxation, yoga, music and audio‐analgesia. Six trials used relaxation. This consisted of relaxation of bodily muscles and use of the breath in one trial (Almeida 2005). Two trials used progressive muscle relaxation (Bagharpoosh 2006; Yildirim 2004). Three trials used psychoprophylaxis (Bergstrom 2009; Dolcetta 1979; Gatelli 2000). Two trials used yoga interventions. Chuntharapat 2008 included postures, breathing, chanting and education, and Phumdoung 2007 reported a yoga intervention using postures. One trial used audio‐analgesia (Moore 1965) and two trials used music (Durham 1986, Liu 2010). The interventions are described in greater detail in the Characteristics of included studies. Details of the comparator group using usual care were frequently under‐reported.

Outcome measures

Nine trials reported data on pain (Almeida 2005; Bagharpoosh 2006; Bergstrom 2009; Chuntharapat 2008; Durham 1986, Liu 2010; Moore 1965; Phumdoung 2007; Yildirim 2004). Maternal outcomes (sense of control, satisfaction) were reported in three trials (Bergstrom 2009; Chuntharapat 2008; Gatelli 2000). No clinical outcomes were reported in two trials (Bagharpoosh 2006; Dolcetta 1979). See details of all outcomes reported within the Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 12 studies; see Characteristics of excluded studies. We excluded two due to insufficient reporting and we were unable to obtain additional information from the authors (Ahmadian 2009; Taghavi 2009). Six studies did not report on any clinically relevant outcomes to pain management (Bastani 2006; Browning 2000; Buxton 1973; ; Phumdoung 2003; Sammons 1984; Schorn 2009). Three studies did not meet the eligibility criteria (Geden 1989; Hao 1997; Ran 2005) and for one study we were unable to obtain data and clarification of randomisation (Podder 2007).

Risk of bias in included studies

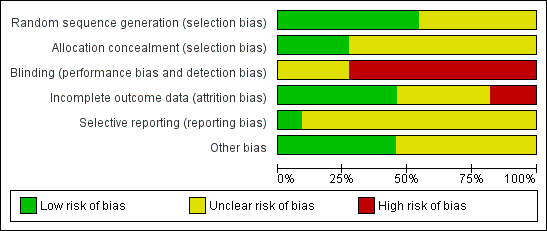

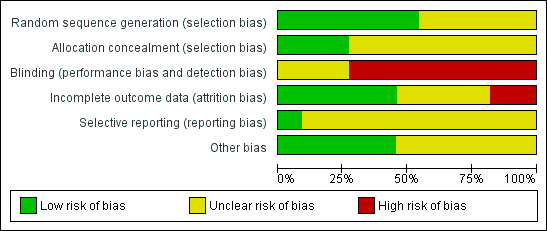

SeeFigure 1 and Figure 2 for a graphical summary of the risk of bias assessment made by the authors. No study was at low risk of bias on all domains.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The method of sequence generation was at low risk of bias in six trials (Almeida 2005; Bergstrom 2009; Chuntharapat 2008; Durham 1986, Phumdoung 2007; Liu 2010). The risk of bias was unclear in the remaining five trials. Allocation concealment was at a low risk of bias in three trials (Almeida 2005; Bergstrom 2009; Liu 2010). The risk of bias was unclear in the remaining eight trials.

Blinding

The interventions could not be administered blind. No trial was at a low risk of bias, and nine trials were at a high risk of bias (Almeida 2005; Bagharpoosh 2006; Bergstrom 2009; Chuntharapat 2008; Durham 1986; Dolcetta 1979; Gatelli 2000; Liu 2010; Phumdoung 2007).

Incomplete outcome data

Outcome reporting was assessed at a low risk of bias in four trials (Almeida 2005; Bergstrom 2009; Moore 1965; Phumdoung 2007).

Selective reporting

The risk of bias was unclear due to insufficient reporting in all but one trial (Bergstrom 2009).

Other potential sources of bias

Five trials were at a low risk of bias (Almeida 2005; Chuntharapat 2008; Dolcetta 1979; Phumdoung 2007; Yildirim 2004).

Effects of interventions

1) Relaxation

There were no data available on the outcomes; sense of control in labour, effect on mother/baby interaction, breastfeeding, admission to nursery and other poor outcomes for infants. We included five trials and 1066 women in the meta‐analysis.

Primary outcomes

1.1) Outcome: pain intensity

Yildirim 2004 found a reduction in pain intensity for women receiving instruction on relaxation during the latent phase (mean difference (MD) ‐1.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.97 to ‐0.53, 40 women), and active phases of labour (MD) ‐2.48, 95% CI ‐3.13 to ‐1.83, two trials, 74 women, I² = 0%).

Data from Almeida 2005 (36 women) were excluded from the analysis due to the large number of post‐randomisation exclusions. There were no differences between groups with the intensity of pain in the latent phase (MD 0.37, 95% CI ‐0.55 to 1.29), active phase (MD 0.54, 95% CI ‐0.25 to 1.33), and transition phase (MD 0.0, 95% CI ‐0.56 to 0.56).

Data from Bagharpoosh 2006 were not reported in full and could not be entered into the meta‐analysis. This trial reported a reduction in the intensity of pain for the group receiving relaxation instruction compared with usual care during the latent phase (4.6 versus 6.3, P = 001), the active phase (7.03 versus 9.12. P = 0.0001) and during the second stage of labour (6.96 versus 9.64, P = 0.001).

1.2) Outcome: maternal perception of pain (memory of pain intensity assessed at follow‐up)

There were no differences between groups in maternal perception of pain (MD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.22, one trial, 904 women) Analysis 1.2.

1.3) Outcome: satisfaction with pain relief in labour

There was an increased satisfaction with pain relief for women receiving relaxation compared with the control (RR 8.00, 95% CI 1.10 to 58.19, one trial, 40 women) Analysis 1.3.

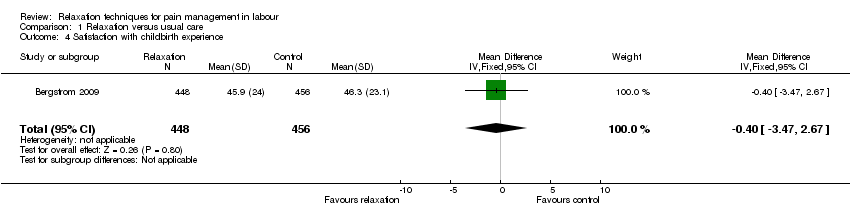

1.4) Outcome: satisfaction with childbirth

There was no difference between groups (MD) ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐3.47 to 2.67, one trial, 904 women) Analysis 1.4 (analysis adjusted for clustering).

1.5) Outcome: assisted vaginal delivery

We did not combine data between the cluster and individualised randomised controlled trials due to significant heterogeneity. We combined data in the two individualised randomised trials and there was a lower rate of assisted vaginal delivery in the relaxation group (RR 0.07, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.50, two trials, 86 women). Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.00; Chi² = 0.65, df = 1 (P = 0.42); I² = 0% Analysis 1.5.

There were no differences between groups in the cluster trial (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.61, one trial, 904 women) (Bergstrom 2009).

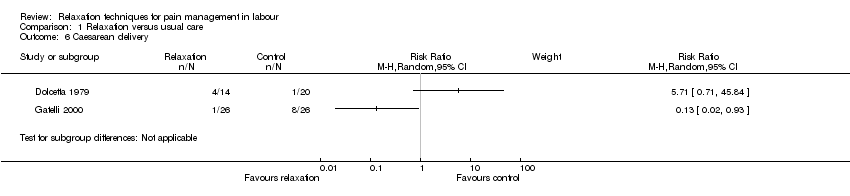

1.6) Outcome: caesarean delivery

We did not combine data between the cluster and individualised randomised controlled trials due to significant heterogeneity (I² = 85%).

There was a lower rate of caesarean delivery in the relaxation group compared with control (Gatelli 2000) (RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.93, 52 women). There was no difference between groups in the Dolcetta 1979 trial (RR 5.71, 95% CI 0.71 to 45.84, 34 women). Analysis 1.6.

There were no differences between groups in the cluster trial (Bergstrom 2009) (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.18, 904 women).

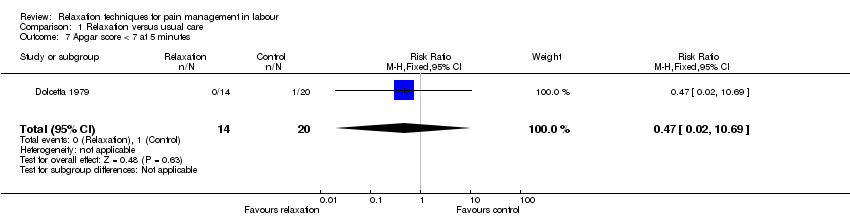

1.7) Outcome: Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

There was no difference between groups (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.02 to 10.69, one trial, 34 women); Analysis 1.7.

Secondary outcomes

There were no data available on the outcomes: spontaneous vaginal delivery; perineal trauma (defined as episiotomy and incidence of second or third degree tear); maternal blood loss (postpartum haemorrhage defined as greater than 500 ml); anxiety.

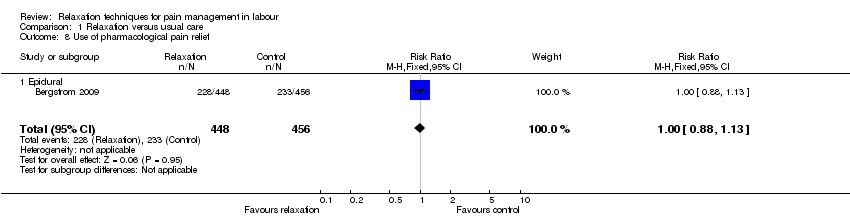

1.8 Outcome: use of pharmacological methods of pain relief

There was no difference between groups with the use of epidural (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.13, one trial, 904 women); Analysis 1.8.

1.9) Outcome: length of labour

There were no difference between groups (MD 105.56, 95% CI ‐1.50 to 212.62, one trial, 36 women) (Almeida 2005). Dolcetta 1979 reported on the active phase of labour and found no difference between groups (251.5 (102.1) versus 318.3 (145.6); Analysis 1.9.

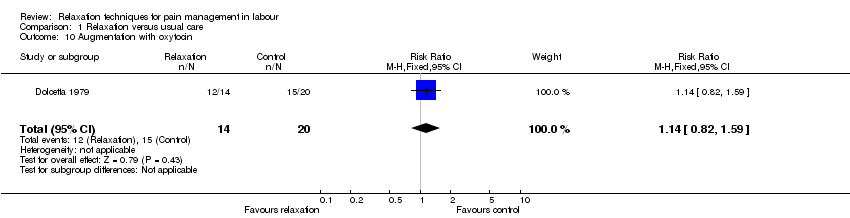

1.10) Outcome: augmentation with oxytocin

There was no difference between groups (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.59, 34 women) (Dolcetta 1979); Analysis 1.10.

2) Yoga

There were no data available on sense of control in labour, maternal perception of pain, assisted vaginal delivery, caesarean delivery, effect on mother/baby interaction, breastfeeding, admission to nursery and other poor infant outcomes. We included two trials and 149 women in the meta‐analysis.

Primary outcomes

2.1) Outcome: pain intensity

There was a reduction in pain intensity for women receiving yoga compared with the control group (MD ‐6.12, 95% CI ‐11.77 to ‐0.47), one trial, 66 women); Analysis 2.1.

2.2) Outcome: satisfaction with pain relief

There was greater satisfaction with pain relief for women receiving yoga compared with the control (MD 7.88, 95% CI 1.51 to 14.25, one trial, 66 women); Analysis 2.2.

2.3) Outcome: satisfaction with childbirth

There was greater satisfaction with childbirth for women receiving yoga compared with the control (MD 6.34, 95% CI 0.26 to 12.42, one trial, 66 women); Analysis 2.3.

2.4) Outcome: Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

No babies in yoga or the control group had an Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; Analysis 2.4.

Secondary outcomes

There were no data available on the outcomes: spontaneous vaginal delivery; perineal trauma (defined as episiotomy and incidence of second or third degree tear); maternal blood loss (postpartum haemorrhage defined as greater than 500 ml); anxiety.

2.5) Outcome: use of pharmacological pain relief

A comparison between yoga and usual care found no difference between groups (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.38, one trial, 66 women).

A comparison between yoga and supine position found reduced use of pharmacological methods for women receiving yoga (RR 0.05, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.35, one trial, 83 women); Analysis 2.5.

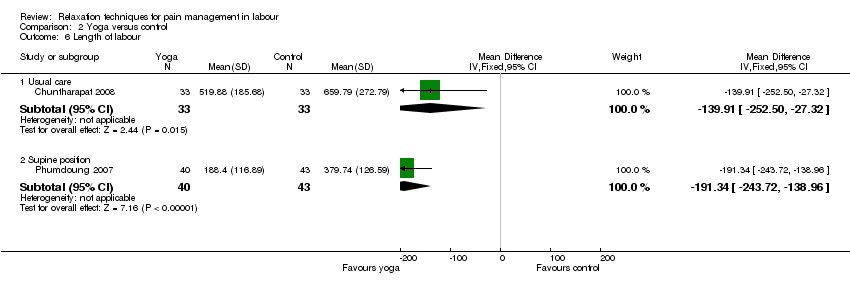

2.6) Outcome: length of active labour

The length of labour was reduced for women receiving yoga compared with usual care (MD ‐139.91, 95% CI ‐252.50 to ‐27.32, one trial, 66 women), and when compared to supine position (MD ‐191.34, 95% CI ‐243.72 to ‐138.96, one trial, 83 women); Analysis 2.6.

2.7) Outcome: augmentation in labour

There was no difference between groups (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.31, one trial, 66 women); Analysis 2.7.

3) Music

There were no data available on satisfaction with pain relief, maternal perception of pain, satisfaction with childbirth, sense of control in labour, assisted vaginal delivery, caesarean delivery, Apgar score less than seven at five minutes, effect on mother/baby interaction, breastfeeding, admission to nursery and other poor outcomes for infants. We included one trial of 60 women in the meta‐analysis. Data from the Durham 1986 trial were not in a form that could be used in the meta‐analysis.

Primary outcomes

3.1) Outcome: pain intensity

There was no difference in pain between groups in the latent phase (MD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐1.41 to 1.07, one trial, 60 women), or the active phase (MD ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐0.70 to 0.34); Analysis 3.1.

3.2) Outcome: caesarean delivery

There was no difference between groups (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.37 to 4.21, one trial, 60 women); Analysis 3.2.

Secondary outcomes

There were no data available on the outcomes: spontaneous vaginal delivery; need for augmentation with oxytocin; perineal trauma (defined as episiotomy and incidence of second or third degree tear); maternal blood loss (postpartum haemorrhage defined as greater than 500 ml).

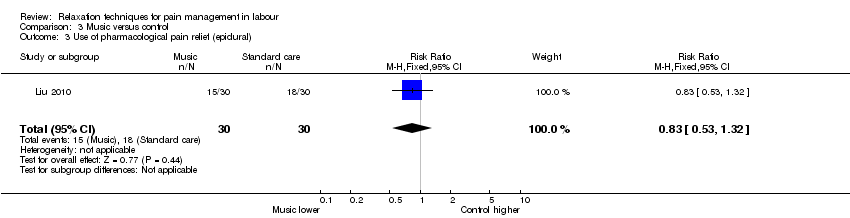

3.3) Use of pharmacological pain relief

There was no difference between groups (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.32, one trial, 60 women) Analysis 3.3. Durham 1986 reported on this outcome and found no difference between groups (Chi² 6.17, P > 0.05).

3.4) Outcome: length of labour

There was no difference between groups (MD ‐2.60, 95% CI ‐11.58 to 6.38, one trial, 60 women).

3.5) Outcome anxiety

There was no difference between groups in the latent (MD 1.18, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 2.49, one trial, 60 women), and the active phase (MD 0.54, 95% CI ‐0.56 to 1.64, one trial, 60 women).

4) Audio‐analgesia

One trial of 24 women was included in the meta‐analysis.

Primary outcome

Only one outcome on maternal satisfaction was reported for this trial.

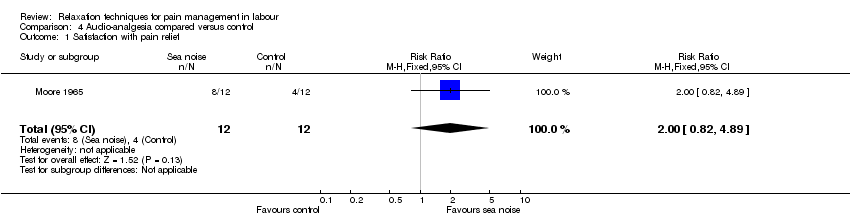

4.1) Outcome: satisfaction with pain relief

There was no difference found between groups (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.82 to 4.89, one trial, 24 women); Analysis 4.1.

Secondary outcomes

There were no data available on the outcomes: use of pharmacological pain relief; length of labour; spontaneous vaginal delivery; need for augmentation with oxytocin; perineal trauma (defined as episiotomy and incidence of second or third degree tear); maternal blood loss (postpartum haemorrhage defined as greater than 500 ml); anxiety.

Sensitivity analysis

It was proposed to undertake a sensitivity analysis on the results to look at the possible contribution of (1) differences in methodological quality, with trials of high quality (low risk of bias) compared to all trials; and (2) publication bias by country. This was not done as there were no trials of high quality, there were also few trials within comparisons to examine the influence of publication bias. Where there was heterogeneity we applied a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis

We undertook no subgroup analysis based on insufficient reporting of trials with the variables of interest.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Eleven studies and 1374 women included in the review suggest current limited evidence of benefit from relaxation techniques in relation to the primary outcomes of reduced pain, increased satisfaction and improved clinical outcomes to mothers and their babies. Relaxation was associated with a reduction in pain intensity during the latent phase, and the active phase of labour. Instruction on relaxation demonstrated increased satisfaction with pain relief, and lower assisted vaginal delivery. Yoga was associated with reduced pain, increased satisfaction with pain relief, and satisfaction with the childbirth experience. Trials evaluating music and audio analgesia found no difference between groups in the primary outcomes of pain intensity, satisfaction with pain relief, and caesarean delivery. Currently there are a small number of trials included within each comparison, and this limits the power of the review to detect meaningful differences between groups and analyses, suggesting these limited benefits should be interpreted with caution.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There are only a few trials with small samples of relaxation, yoga, music and audio‐analgesia interventions that assess the role of these therapies for pain management in labour. The completeness and applicability of the evidence is limited from these 11 trials, and there are no well designed trials at a low risk of bias. The inclusion of relevant outcomes was limited in the majority of trials with a lack of outcome relating to both safety and effectiveness.

Trials recruited nulliparous and multiparous women, from both the second and third trimester of pregnancy, with the interventions administered in the antenatal and labour ward environment. Some trials recruited women during labour during and taught women relaxation techniques during this time. This maybe not result in the most efficacious practise of relaxation techniques, which may requires significant time to practise and master. Studies were conducted in different countries, and this may reflect the use of particular modalities or techniques as part of their culture. The systematic review illustrates variation in how these modalities were practised, although it is unclear how representative the treatment protocols used in the research are generalisable to clinical practice or practice within the community.

Quality of the evidence

The risk of bias table (Figure 1, Figure 2) demonstrates relaxation techniques have not been subject to consistent rigorous evaluation. The quality of reporting was poor in 90% of trials, consequently it is difficult to assess the overall risk of bias across studies and domains. Overall the risk of bias was low in one trial (Bergstrom 2009). For many studies, blinding of participants and the practitioner was not possible, and reporting indicated that some outcomes may have been influenced by a lack of blinding, and consequently were rated at a high risk of bias. The small number of studies within comparisons and lack of high‐quality trials indicates there is currently insufficient evidence of a consistent treatment effect from the relaxation modalities included in the review. The chief investigators of some studies were contacted to provide additional methodological and statistical information: however; only a few responses were obtained (Liu 2010; Phumdoung 2007).

The quality of evidence was affected by unexplained heterogeneity in some comparisons arising from the clinical heterogeneity of the relaxation modality and study designs. The small numbers of studies within comparisons, and lack of high‐quality trials prevented further investigation of the heterogeneity and the impact on treatments effects.

Potential biases in the review process

We attempted to minimise bias during the review process. Two authors assessed the eligibility of studies, carried out data extraction and assessed the risk of bias. We are aware that some literature on relaxation therapies may not be published in mainstream journals and therefore maybe excluded from the main databases. Our search was comprehensive and we included studies identified in languages other than English, we cannot rule out the possibility that some studies may have been missed.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Due to the lack of research examining the effect of relaxation modalities on pain management in labour we are limited to making comparisons with other trials and reviews.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 1 Pain intensity.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 2 Maternal perception of pain.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 3 Satisfaction with pain relief in labour.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 4 Satisfaction with childbirth experience.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 5 Assisted vaginal delivery.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 6 Caesarean delivery.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 7 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 8 Use of pharmacological pain relief.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 9 Length of labour.

Comparison 1 Relaxation versus usual care, Outcome 10 Augmentation with oxytocin.

Comparison 2 Yoga versus control, Outcome 1 Pain intensity.

Comparison 2 Yoga versus control, Outcome 2 Satisfaction with pain relief.

Comparison 2 Yoga versus control, Outcome 3 Satisfaction with childbirth experience.

Comparison 2 Yoga versus control, Outcome 4 Apgar score less than seven at five minutes.

Comparison 2 Yoga versus control, Outcome 5 Use of pharmacological pain relief.

Comparison 2 Yoga versus control, Outcome 6 Length of labour.

Comparison 2 Yoga versus control, Outcome 7 Augmentation with oxytocin.

Comparison 3 Music versus control, Outcome 1 Pain intensity.

Comparison 3 Music versus control, Outcome 2 Caesarean section.

Comparison 3 Music versus control, Outcome 3 Use of pharmacological pain relief (epidural).

Comparison 3 Music versus control, Outcome 4 Length of labour.

Comparison 3 Music versus control, Outcome 5 Anxiety.

Comparison 4 Audio‐analgesia compared versus control, Outcome 1 Satisfaction with pain relief.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Pain intensity Show forest plot | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Latent phase | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.25 [‐1.97, ‐0.53] |

| 1.2 Active phase | 2 | 74 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.48 [‐3.13, ‐1.83] |

| 1.3 Transition | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Maternal perception of pain Show forest plot | 1 | 904 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.22, 0.22] |

| 3 Satisfaction with pain relief in labour Show forest plot | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.0 [1.10, 58.19] |

| 4 Satisfaction with childbirth experience Show forest plot | 1 | 904 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐3.47, 2.67] |

| 5 Assisted vaginal delivery Show forest plot | 2 | 86 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.01, 0.50] |

| 6 Caesarean delivery Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes Show forest plot | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.02, 10.69] |

| 8 Use of pharmacological pain relief Show forest plot | 1 | 904 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.88, 1.13] |

| 8.1 Epidural | 1 | 904 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.88, 1.13] |

| 9 Length of labour Show forest plot | 1 | 36 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 105.56 [‐1.50, 212.62] |

| 10 Augmentation with oxytocin Show forest plot | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.82, 1.59] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Pain intensity Show forest plot | 1 | 66 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.12 [‐11.77, ‐0.47] |

| 1.1 Latent phase | 1 | 66 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.12 [‐11.77, ‐0.47] |

| 2 Satisfaction with pain relief Show forest plot | 1 | 66 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.88 [1.51, 14.25] |

| 2.1 Latent phase | 1 | 66 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.88 [1.51, 14.25] |

| 3 Satisfaction with childbirth experience Show forest plot | 1 | 66 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.34 [0.26, 12.42] |

| 3.1 Usual care | 1 | 66 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.34 [0.26, 12.42] |

| 4 Apgar score less than seven at five minutes Show forest plot | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Use of pharmacological pain relief Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Usual care | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.49, 1.38] |

| 5.2 Supine position | 1 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.05 [0.01, 0.35] |

| 6 Length of labour Show forest plot | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Usual care | 1 | 66 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐139.91 [‐252.50, ‐27.32] |

| 6.2 Supine position | 1 | 83 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐191.34 [‐243.72, ‐138.96] |

| 7 Augmentation with oxytocin Show forest plot | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.45, 1.31] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Pain intensity Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Latent phase | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐1.41, 1.07] |

| 1.2 Active phase | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.18 [‐0.70, 0.34] |

| 2 Caesarean section Show forest plot | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.37, 4.21] |

| 3 Use of pharmacological pain relief (epidural) Show forest plot | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.53, 1.32] |

| 4 Length of labour Show forest plot | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.60 [‐11.58, 6.38] |

| 4.1 Second stage | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.60 [‐11.58, 6.38] |

| 5 Anxiety Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Latent phase | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [‐0.13, 2.49] |

| 5.2 Active phase | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [‐0.56, 1.64] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Satisfaction with pain relief Show forest plot | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.82, 4.89] |