Insuflaciones sostenidas versus estándar durante la reanimación neonatal para prevenir la mortalidad y mejorar los resultados respiratorios

Resumen

Antecedentes

Al nacer, los pulmones de los recién nacidos están llenos de líquido. Para que los recién nacidos tengan una transición exitosa, este líquido debe ser reemplazado por aire para permitir el intercambio gaseoso. Cuando se considera que algunos recién nacidos presentan una respiración inadecuada al nacer, se les reanima con ventilación con presión positiva (VPP). Proporcionar insuflaciones prolongadas (sostenidas) al comienzo de la VPP puede ayudar a eliminar el líquido pulmonar y establecer el volumen de gas en los pulmones.

Objetivos

Evaluar los efectos beneficiosos y perjudiciales de una insuflación pulmonar sostenida inicial (IPS) (> 1 segundo de duración) versus insuflaciones estándar (≤ 1 segundo) en recién nacidos que reciben reanimación con VPP intermitente.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se utilizó la estrategia de búsqueda estándar del Grupo Cochrane de Neonatología en el Registro Cochrane Central de Ensayos Controlados (CENTRAL; 2019, Número 3), MEDLINE vía PubMed (1966 hasta el 1 de abril 2019), Embase (1980 hasta el 1 de abril 2019) y en Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; 1982 al 1 de abril 2019). También se buscaron ensayos controlados aleatorizados y cuasialeatorizados en las bases de datos de ensayos clínicos, las actas de congresos y las listas de referencias de los artículos recuperados..

Criterios de selección

Ensayos controlados aleatorizados (ECA) y cuasialeatorizados que compararon proporcionar insuflaciones pulmonares sostenidas (IPS) iniciales versus insuflaciones estándar a los recién nacidos que recibieron reanimación con VPP al nacer.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

La calidad metodológica de los ensayos incluidos se evaluó mediante los criterios del Grupo Cochrane para una Práctica y Organización Sanitaria Efectivas (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group) (EPOC) (que evalúan la asignación al azar, el cegamiento, la pérdida durante el seguimiento y el procesamiento de los datos de resultado). El efecto del tratamiento se evaluó mediante el modelo de efectos fijos con el riesgo relativo (RR) para los datos categóricos y la media, la desviación estándar (DE) y la diferencia de medias ponderada (DMP) para los datos continuos. Se utilizaron los criterios GRADE para evaluar la calidad de la evidencia.

Resultados principales

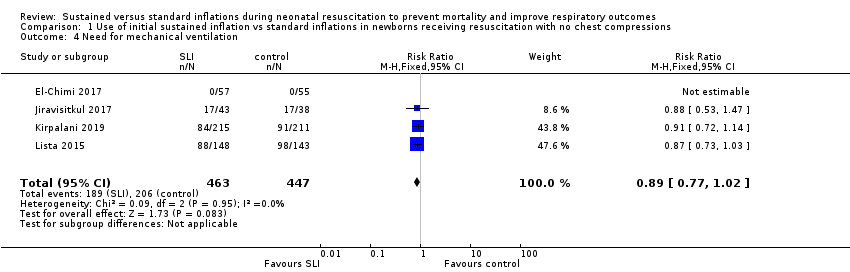

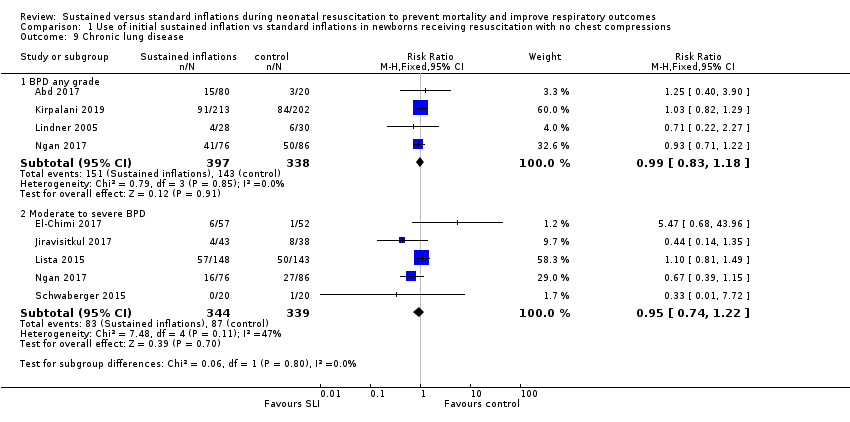

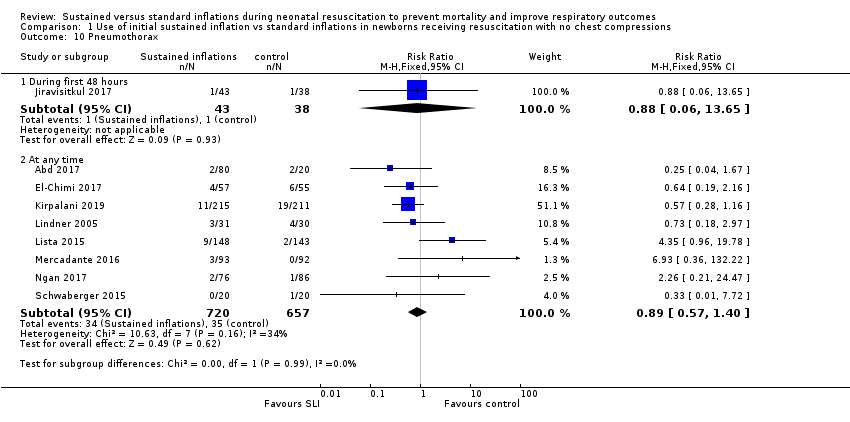

Diez estudios con 1467 recién nacidos cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. Los investigadores de nueve ensayos (1458 recién nacidos) administraron insuflación sostenida sin compresiones torácicas. El uso de la insuflación sostenida no tuvo una repercusión en los resultados primarios de esta revisión: mortalidad en la sala de partos (RR típico 2,66; intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 0,11 a 63,40 [I² no aplicable]; DR típica 0,00; IC del 95%: ‐0.02 a 0,02; I² = 0%; cinco estudios, 479 participantes); ni la mortalidad durante la hospitalización (RR típico 1,09; IC del 95%: 0,83 a 1,43; I² = 42%; DR típica 0,01; IC del 95%: ‐0,02 a 0,04; I² = 24%; nueve estudios, 1458 participantes). La calidad de la evidencia fue baja para la muerte en la sala de partos debido a las limitaciones en el diseño de los estudios y a la imprecisión de las estimaciones (solo se registró una muerte en todos los estudios). En el caso de la muerte antes del alta, la calidad fue moderada: con un seguimiento más largo hubo más muertes (n = 143) pero se mantuvieron las limitaciones en el diseño de los estudios. Entre las medidas de resultado secundarias, la duración de la ventilación mecánica fue más corta en el grupo de IPS (diferencia de medias [DM] ‐5,37 días; IC del 95%: ‐6,31 a ‐4,43; I² = 95%; cinco estudios, 524 participantes; evidencia de calidad baja). La heterogeneidad, la significación estadística y la magnitud de los efectos de este resultado están en gran medida influenciados por un solo estudio con alto riesgo de sesgo, cuando este estudio se retiró del análisis el tamaño del efecto se redujo (DM ‐1,71 días; IC del 95%: ‐3,04 a ‐0,39; I² = 0%). Los resultados no mostraron diferencias en las otras medidas de resultado secundarias (p.ej., riesgo de intubación endotraqueal fuera de la sala de partos a las 72 horas de vida (RR típico 0,91; IC del 95%: 0,79 a 1,04; I² = 65%; cinco estudios, 811 participantes); riesgo de administración de surfactante durante el ingreso hospitalario (RR típico 0,99; IC del 95%: 0,91 a 1.08; I² = 0%; nueve estudios, 1458 participantes); riesgo de enfermedad pulmonar crónica (RR típico 0,99; IC del 95%: 0,83 a 1,18; I² = 0%; cuatro estudios, 735 participantes); neumotórax (RR típico 0,89; IC del 95%: 0.57 a 1,40; I² = 34%; ocho estudios, 1377 lactantes) o riesgo de conducto arterioso persistente que requiere tratamiento farmacológico (RR típico 0,99; IC del 95%: 0,87 a 1,12; I² = 48%; siete estudios, 1127 lactantes). La calidad de la evidencia para estos resultados secundarios fue moderada (limitaciones en el diseño, según criterios GRADE) excepto para el neumotórax (calidad baja: limitaciones en el diseño de los estudios e imprecisión de las estimaciones, según criterios GRADE). No fue posible realizar un metanálisis en la comparación del uso de insuflación inicial sostenida versus insuflaciones estándar en recién nacidos que reciben reanimación con compresiones torácicas porque solo se identificó un ensayo para inclusión (un estudio piloto con nueve recién nacidos prematuros).

Conclusiones de los autores

El metanálisis de nueve estudios muestra que la insuflación pulmonar sostenida sin compresión torácica no fue mejor que la ventilación intermitente para reducir la mortalidad en la sala de partos (evidencia de calidad baja, según criterios GRADE) o durante la hospitalización (evidencia de calidad moderada, según criterios GRADE), que fueron los resultados primarios de esta revisión. Sin embargo, el estudio de mayor duración, que fue bien realizado y contó con el mayor número de lactantes reclutados, se interrumpió de forma temprana por una mayor tasa de mortalidad en el grupo de insuflación sostenida. Al considerar los resultados secundarios, como la tasa de intubación, la tasa o duración de la asistencia respiratoria o la displasia broncopulmonar, no se encontró un efecto beneficioso de la insuflación sostenida sobre la ventilación intermitente (evidencia de calidad moderada, según criterios GRADE). La duración de la ventilación mecánica se acortó en el grupo de IPS (evidencia de calidad baja,según criterios GRADE); sin embargo, este resultado se debe interpretar con cautela, ya que podría haber estado influenciado por características del estudio distintas de la intervención. No hay evidencia que apoye el uso de la insuflación sostenida sobre la base de la evidencia de esta revisión.

PICO

Resumen en términos sencillos

Insuflación pulmonar prolongada para la reanimación de los recién nacidos en el parto

Pregunta de la revisión

El uso de insuflaciones pulmonares sostenidas (> 1 segundo de duración) en comparación con las insuflaciones estándar (≤ 1 segundo), ¿mejora la supervivencia y otros resultados importantes en los recién nacidos que reciben reanimación al nacer?

Antecedentes

Al nacer, los pulmones están llenos de líquido que se debe reemplazar con aire para que los recién nacidos respiren de manera adecuada. Algunos recién nacidos tienen dificultad para establecer una respiración efectiva al nacer y uno de cada 20 a 30 recién nacidos debe recibir ayuda para hacerlo. Para ayudar a los recién nacidos a comenzar a respirar normalmente se utilizan diversos dispositivos. Algunos de estos dispositivos les permiten a los cuidadores proporcionar insuflaciones prolongadas (o sostenidas). Estas insuflaciones sostenidas pueden ayudar a inflar los pulmones y mantenerlos inflados mejor, en comparación con no utilizarlas.

Características de los estudios

Se recopilaron y analizaron todos los estudios relevantes para responder a esta pregunta y se encontraron diez estudios con 1467 recién nacidos. En todos los estudios, los neonatos nacieron antes de la fecha prevista de parto (de 23 a 36 semanas de edad gestacional). La insuflación sostenida duró entre 15 y 20 segundos a una presión entre 20 y 30 cmH₂O. La mayoría de los estudios proporcionaron una o más insuflaciones sostenidas adicionales en los casos de respuesta clínica deficiente, por ejemplo, frecuencia cardíaca baja persistente. Un estudio (que incluyó solo nueve recién nacidos) se analizó por separado porque los investigadores combinaron el uso de insuflaciones sostenidas o estándar con compresiones torácicas, una intervención adicional que podría ayudar a los neonatos a comenzar a respirar normalmente.

Resultados clave

Los estudios incluidos no mostraron diferencias importantes entre los recién nacidos que recibieron insuflaciones sostenidas versus estándar en cuanto a la mortalidad, la tasa de intubación durante los primeros tres días de vida o la enfermedad pulmonar crónica. Los recién nacidos que reciben insuflación sostenida al nacer pueden pasar menos días con ventilación mecánica. Es posible que los resultados de varios estudios en curso ayuden a determinar si las insuflaciones sostenidas tienen efectos beneficiosos o perjudiciales. En la actualidad no se pueden excluir diferencias pequeñas o moderadas entre los dos tratamientos.

Calidad de la evidencia

La calidad de la evidencia es muy baja a moderada debido a que solo un escaso número de estudios ha examinado esta intervención; el número total de recién nacidos incluidos en estos estudios fue bajo y algunos estudios podrían haber tenido un mejor diseño.

¿Cómo de actualizada está esta revisión?

Se hicieron búsquedas de estudios que se habían publicado hasta abril de 2019.

Conclusiones de los autores

Summary of findings

| Use of initial sustained inflation compared to standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions during resuscitation | ||||||

| Population: preterm infants resuscitated by PPV at birth | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No. of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions | Use of initial sustained inflation | |||||

| Death ‒in the delivery room | Study population | RR 2.66 | 479 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Death ‒before discharge | Study population | RR 1.09 | 1458 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | ||

| 112 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 58 per 1000 | 63 per 1000 | |||||

| Rate of mechanical ventilation | Study population | RR 0.89 | 910 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | ||

| 461 per 1000 | 410 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 439 per 1000 | 391 per 1000 | |||||

| Chronic lung disease ‒any grade | Study population | RR 0.98 | 1418 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | ||

| 340 per 1000 | 333 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 211 per 1000 | 207 per 1000 | |||||

| Chronic lung disease ‒moderate to severe BPD | Study population | RR 0.95 | 683 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | ||

| 257 per 1000 | 244 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 211 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 | |||||

| Pneumothorax | Study population | RR 0.89 | 1458 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| 52 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 50 per 1000 | 44 per 1000 | |||||

| Cranial ultrasound abnormalities ‒Intraventricular haemorrhage grade 3 to 4 | Study population | RR 0.85 | 735 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| 116 per 1000 | 99 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 54 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1 all studies at high or unclear risk of bias in at least one domain (lack of blinding) and 1 study stopped early | ||||||

| Use of initial sustained inflation for | ||||||

| Population: infants below 33 weeks of postmenstrual age who required resuscitation in the delivery room | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No. of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Use of initial sustained inflation | |||||

| Death ‒in the delivery room | See comment | See comment | not reported | 9 (1 study) | The included study did not report on this outcome | |

| Death ‒before discharge | Study population | RR 4.17 | 9 | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Rate of mechanical ventilation | See comment | See comment | not reported | 9 (1 study) | The included study did not report on this outcome | |

| Chronic lung disease ‒any grade | See comment | See comment | not reported | 9 (1 study) | The included study did not report on this outcome | |

| Chronic lung disease ‒moderate to severe BPD | Study population | RR 0.89 | 7 | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ | ||

| 750 per 1000 | 668 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 750 per 1000 | 668 per 1000 | |||||

| Pneumothorax ‒at any time | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 9 | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ | No events |

| Cranial ultrasound abnormalities ‒intraventricular haemorrhage grade 3 to 4 | Study population | RR 0.4 | 9 | ⊝⊝⊝⊝ | ||

| 500 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 200 per 1000 | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1 Limitations in study design: downgraded by 1 level due to included study at high or unclear risk of bias in 4 domains | ||||||

Antecedentes

Descripción de la afección

Al nacer, los pulmones de los recién nacidos se llenan de líquido que se debe eliminar para que la respiración sea eficaz. La mayoría de los recién nacidos lo logran de forma espontánea y pueden utilizar una considerable presión negativa (hasta ‐50 cmH₂O) para las inspiraciones iniciales (Karlberg 1962; Milner 1977). Sin embargo, se calcula que entre el 3% y el 5% de los recién nacidos reciben alguna ayuda para respirar durante el parto (Saugstad 1998). La ventilación adecuada es la clave para el éxito de la reanimación y estabilización neonatal (Wyckoff 2015). La ventilación con presión positiva (VPP) se recomienda en los lactantes que no realizan esfuerzos respiratorios o los realizan de forma inadecuada, o que presentan bradicardia (o ambos) al nacer (Wyckoff 2015). Se aconseja el uso de dispositivos de ventilación manual (bolsas autoinflables, bolsas de flujo‐inflables [o de anestesia] y dispositivos mecánicos con tubo en T) con una máscara facial o un tubo endotraqueal (TET). Aunque no figura en las guías del International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR), se ha descrito la asistencia respiratoria de los lactantes en la sala de partos con un ventilador mecánico y un tubo nasofaríngeo (Lindner 1999).

Descripción de la intervención

Los dispositivos recomendados para la VPP en la sala de partos difieren en cuanto a las características físicas y a la capacidad de producir una insuflación pulmonar sostenida (IPS). La bolsa autoinflable más utilizada puede ser de tamaño insuficiente para mantener una insuflación sostenida (> 1 segundo) (O'Donnell 2004a; O'Donnell 2004b). Las bolsas de flujo‐inflables y los dispositivos mecánicos con tubo en T se pueden utilizar para realizar insuflaciones de más de un segundo. Además, muchas de las bolsas autoinflables no son satisfactorias para suministrar un volumen apropiado, principalmente debido a las graves fugas en las válvulas de las bolsas (Tracy 2019). Aunque las presiones de insuflación pretendidas y los largos tiempos de inspiración se logran de manera más consistente con los modelos mecánicos cuando se utilizan dispositivos con tubo en T en lugar de bolsas, no se puede recomendar qué dispositivo es preferible (Wyckoff 2015; Wyllie 2015). La presión positiva al final de la espiración (PEEP) es muy importante para airear los pulmones y mejorar la oxigenación; la IPS consiste en una PEEP de alto nivel prolongada o, más precisamente, una presión de insuflación máxima prolongada.

De qué manera podría funcionar la intervención

Cuando las vías respiratorias están llenas de líquido, podría no ser necesario interrumpir las presiones de insuflación para permitir que el pulmón se desinfle y exhale CO₂ (Hooper 2016). Boon 1979 describió un estudio con 20 lactantes a término nacidos por cesárea bajo anestesia general que fueron reanimados con dispositivos con tubo en T mediante un TET. Los autores del estudio informaron que el gas continuó fluyendo a través del sensor de flujo colocado entre el tubo en T y el TET hacia el lactante al final de una insuflación estándar de un segundo en los rastros respiratorios obtenidos (Boon 1979). Sobre la base de esta observación, este grupo realizó un ensayo no aleatorizado de insuflaciones sostenidas proporcionadas mediante un tubo en T y un TET a nueve lactantes a término durante la reanimación en la sala de partos. Los investigadores informaron que la insuflación inicial con un tubo en T que duraba cinco segundos produjo un aumento del doble del volumen de la insuflación en comparación con las técnicas de reanimación estándar (Vyas 1981). Citando estos hallazgos, un estudio retrospectivo de cohorte describió los efectos de un cambio en la estrategia de tratamiento de los recién nacidos con un peso extremadamente bajo al nacer en la sala de partos (Lindner 1999). La nueva estrategia de tratamiento incluyó la introducción de una insuflación inicial sostenida de 15 segundos lograda con un ventilador mecánico a través de un tubo nasofaríngeo. Este cambio de estrategia se asoció con una reducción en la proporción de lactantes intubados para recibir asistencia respiratoria continua sin un aumento aparente de los resultados adversos. Se informó de que la morbilidad pulmonar en los lactantes con muy bajo peso al nacer estuvo directamente relacionada con la mortalidad en el 50% de los casos de muerte (Drew 1982). Además, las IPS múltiples en lactantes muy prematuros mejoraron la frecuencia cardíaca y la saturación de oxígeno del tejido cerebral, sin provocar efectos perjudiciales (Fuchs 2011). Un estudio observacional mostró que la insuflación sostenida de 10 segundos a 25 cmH₂O en 70 lactantes muy prematuros al nacer no fue eficaz en los lactantes que no respiraban, posiblemente debido a la aducción glótica activa (van Vonderen 2014). Los recién nacidos suelen hacer una inspiración y luego prolongan la expiración mediante el cierre de la glotis y el frenado diafragmático, lo que provoca que se prolongue la presión del final de la expiración.

Por qué es importante realizar esta revisión

Las recomendaciones relacionadas con el uso de la insuflación sostenida al nacer han variado entre los distintos organismos internacionales. Aunque las guías del European Resuscitation Council indican proporcionar cinco respiraciones de insuflación si el recién nacido jadea o no respira (Wyllie 2015), la American Heart Association afirma que la evidencia no es suficiente para recomendar un tiempo de insuflación óptimo (Wyckoff 2015). Las diferencias entre estas guías y sus algoritmos son curiosas (Klingenberg 2016). Una revisión narrativa informó que la insuflación sostenida puede reducir la necesidad de ventilación mecánica entre los lactantes prematuros en riesgo de padecer el síndrome de dificultad respiratoria (SDR) (Lista 2010). La misma revisión mostró que los resultados respiratorios de los lactantes que recibieron una insuflación sostenida (25 cmH₂O durante 15 segundos) mejoraron con respecto a los registrados en un grupo histórico (Lista 2011).

La revisión anterior "Insuflaciones sostenidas versus estándar durante la reanimación neonatal para prevenir la mortalidad y mejorar los resultados respiratorios" incluyó ocho ensayos con 941 participantes (Bruschettini 2017). La insuflación sostenida no fue mejor que la ventilación intermitente para reducir la mortalidad, la necesidad de intubación, la necesidad o la duración de la asistencia respiratoria o la displasia broncopulmonar. La calidad de la evidencia de estos resultados fue baja a moderada. Esta versión actualizó la revisión anterior que se publicó en la Base de Datos Cochrane de Revisiones Sistemáticas (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) en 2017 (Bruschettini 2017).

Objetivos

Evaluar los efectos beneficiosos y perjudiciales de una insuflación pulmonar sostenida inicial (IPS) (> 1 segundo de duración) versus insuflaciones estándar (≤ 1 segundo) en recién nacidos que reciben reanimación con VPP intermitente.

Métodos

Criterios de inclusión de estudios para esta revisión

Tipos de estudios

Se incluyeron ensayos controlados aleatorizados (ECA) y ensayos controlados cuasialeatorizados. Se excluyeron los estudios observacionales (estudios de casos y controles, series de casos) y los ECA grupales.

Tipos de participantes

Lactantes a término y prematuros reanimados mediante VPP al nacer.

Tipos de intervenciones

Las intervenciones incluyeron la reanimación con una insuflación inicial sostenida (> 1 segundo) versus la reanimación con insuflaciones regulares (≤ 1 segundo):

-

sin compresiones torácicas como parte de la reanimación inicial; o

-

con compresiones torácicas como parte de la reanimación inicial.

Tipos de medida de resultado

Resultados primarios

-

Muerte en la sala de partos

-

Muerte durante la hospitalización

-

Muerte hasta el último seguimiento

Resultados secundarios

-

Frecuencia cardíaca a los 5 minutos

-

La intubación endotraqueal en la sala de partos

-

Intubación endotraqueal en las primeras 72 horas de vida

-

Administración de surfactante en la sala de partos o durante el ingreso hospitalario

-

Ventilación mecánica (sí/no)

-

Duración en horas de la asistencia respiratoria (es decir, la presión nasal continua de las vías respiratorias y la ventilación a través de un TET consideradas por separado y en total)

-

Duración en días de las necesidades de oxígeno suplementario

-

Enfermedad pulmonar crónica: tasa de oxígeno suplementario a los 28 días de vida; tasa de oxígeno suplementario a las 36 semanas de vida posmenstrual para los lactantes nacidos a las 32 semanas de gestación o antes de ellas

-

Las pérdidas de aire (neumotórax, neumomediastino, neumopericardio, enfisema pulmonar intersticial) informadas individualmente o como resultado compuesto.

-

Anomalías en la ecografía craneal: cualquier hemorragia intraventricular (Hiv), grado 3 o 4 según la clasificación de Papile (Papile 1978) y leucomalacia periventricular quística

-

Crisis convulsivas clínicas y electroencefalográficas

-

Encefalopatía hipóxica‐isquémica en lactantes prematuros a término y tardíos (grado 1 a 3 [Sarnat 1976])

-

Resultados del desarrollo neurológico a largo plazo (tasas de parálisis cerebral según la evaluación del médico, retraso en el desarrollo (es decir, cociente intelectual [CI] 2 desviaciones estándar [DE] < media en la herramienta de evaluación validada [p.ej., el Bayley's Mental Developmental Index])

-

Retinopatía del prematuro (RP) (todas los estadios y ≥ estadio 3)

-

Conducto arterioso persistente (CAP) (tratamiento farmacológico y ligadura quirúrgica)

Métodos de búsqueda para la identificación de los estudios

We used the criteria and standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal (see the Cochrane Neonatal search strategy for specialised register).

Búsquedas electrónicas

We conducted a comprehensive search that included the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 3) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE via PubMed (1966 to 1 April 2019); Embase (1980 to 1 April 2019); and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to 1 April 2019). See Appendix 1 for full search strategy for each database. We did not apply language restrictions.

We searched clinical trials registries for ongoing and recently completed trials (ClinicalTrials.gov; the World Health Organization International Trials Registry and Platform ‒ www.whoint/ictrp/search/en; and the ISRCTN Registry).

Búsqueda de otros recursos

We also searched abstracts of the Pediatric Academic Society (PAS) from 2000 to 2019, electronically through the PAS website, using the following key words: "sustained inflation" AND "clinical trial".

Obtención y análisis de los datos

We used the standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal.

Selección de los estudios

For this update, two review authors (MB, MGC) independently screened all titles and abstracts to determine which trials met the inclusion criteria. We retrieved full‐text copies of all papers that were potentially relevant. We resolved disagreements by discussion between review authors.

Extracción y manejo de los datos

Two review authors (MB, MGC) independently undertook data abstraction using a data extraction form developed ad hoc and integrated with a modified version of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) data collection checklist (EPOC 2015).

We extracted the following characteristics from each included trial.

-

Administrative details: study author(s); published or unpublished; year of publication; year in which trial was conducted; details of other relevant papers cited.

-

Trial details: study design; type, duration, and completeness of follow‐up; country and location of study; informed consent; ethics approval.

-

Details of participants: birth weight; gestational age; number of participants.

-

Details of intervention: type of ventilation device used; type of interface; duration and level of pressure of sustained lung inflation (SLI).

-

Details of outcomes: death during hospitalisation or to latest follow‐up; heart rate at 5 minutes; duration in hours of respiratory support; duration in days of supplemental oxygen requirement; long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes; any adverse events.

We resolved disagreements by discussion between review authors. When available, we described ongoing trials identified by detailing primary trial author, research question(s) posed, and methods and outcome measures applied, together with an estimate of the reporting date.

When queries arose or additional data were required, we contacted trial authors.

Evaluación del riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos

Two review authors (MB, MGC) independently assessed risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials for the following domains using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool (Higgins 2011).

-

Sequence generation (selection bias).

-

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

-

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

-

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

-

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

-

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

-

Any other bias.

We resolved disagreements by discussion or via consultation with a third assessor. See Appendix 2 for a detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment)

Random sequence generation

For each included trial, we categorised risk of bias regarding random sequence generation as follows.

-

Low risk ‒ adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator).

-

High risk ‒ inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number).

-

Unclear risk ‒ no or unclear information provided.

Allocation concealment

For each included trial, we categorised risk of bias regarding allocation concealment as follows.

-

Low risk ‒ adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes).

-

High risk ‒ inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth).

-

Unclear risk ‒ no or unclear information provided.

Performance bias

Owing to the nature of the intervention, all trials were unblinded, leading to high risk of performance bias.

Detection bias

For each included trial, we categorised the methods used to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or different classes of outcomes.

Attrition bias

For each included trial and for each outcome, we described completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from analysis. We noted whether attrition and exclusions were reported, numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total number of randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion when reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes.

Reporting bias

For each included trial, we described how we investigated the risk of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. We assessed methods as follows.

-

Low risk ‒ adequate (when it is clear that all of a trial's prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported).

-

High risk ‒ inadequate (when not all of a trial's prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so cannot be used; or the trial failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to be reported).

-

Unclear risk ‒ no or unclear information provided (study protocol was not available).

Other bias

For each included trial, we described any important concerns that we had about other possible sources of bias (e.g. whether a potential source of bias was related to the specific trial design, whether the trial was stopped early owing to some data‐dependent process). We assessed whether each trial was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias as follows.

-

Low risk ‒ no concerns of other bias raised.

-

High risk ‒ concerns raised about multiple looks at data with results made known to investigators, differences in numbers of participants enrolled in abstract, and final publications of the paper.

-

Unclear ‒ concerns raised about potential sources of bias that could not be verified by contacting trial authors.

We did not score blinding of the intervention because this was not applicable.

One review author entered data into RevMan Web, and a second review author checked entered data for accuracy.

Medidas del efecto del tratamiento

We conducted measures of treatment effect data analysis using RevMan Web. We determined outcome measures for dichotomous data (e.g. death, endotracheal intubation in the delivery room, frequency of retinopathy) as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We calculated continuous data (e.g. duration of respiratory support, Apgar score) using mean differences (MDs) and SDs.

Cuestiones relativas a la unidad de análisis

The unit of randomisation was the intended unit of analysis (individual neonate).

Manejo de los datos faltantes

We contacted trial authors to request missing data when needed.

Evaluación de la heterogeneidad

As a measure of consistency, we used the I² statistic and the Q (Chi²) test (Deeks 2011). We judged statistical significance of the Q (Chi²) statistic by P < 0.10 because of the low statistical power of the test. We used the following cut‐offs for heterogeneity: less than 25% no heterogeneity; 25% to 49% low heterogeneity; 50% to 74% moderate heterogeneity; and ≥ 75% high heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). We combined trial results using the fixed‐effect model, regardless of statistical evidence of heterogeneity effect sizes.

Evaluación de los sesgos de notificación

See Appendix 2.

Síntesis de los datos

We performed statistical analyses using RevMan Web. We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group. For categorical data, we used RRs, relative risk reductions, and absolute risk difference (RDs). We obtained means and SDs for continuous data and performed analyses using MDs and WMDs when appropriate. We calculated 95% CIs. We presented the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH), as appropriate. For each comparison reviewed, meta‐analysis could be feasible if we identified more than one eligible trial, and if homogeneity among trials was sufficient with respect to participants and interventions. We combined trials using the fixed‐effect model, regardless of statistical evidence of heterogeneity effect sizes. For estimates of RR and RD, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method.

Análisis de subgrupos e investigación de la heterogeneidad

We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses of the safety and efficacy of sustained inflation during resuscitation in subgroups.

-

Term (≥ 37 weeks of gestation) and preterm (< 37 weeks of gestation) infants.

-

Type of ventilation device used (self‐inflating bag, flow‐inflating bag, T‐piece, mechanical ventilator).

-

Interface used (i.e. face mask, ETT, nasopharyngeal tube).

-

Duration of sustained lung inflation (i.e. > 1 second to 5 seconds, > 5 seconds).

Análisis de sensibilidad

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to explore effects of the methodological quality of trials and check to ascertain whether studies with high risk of bias overestimated treatment effects.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the quality of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes: death in the delivery room or during hospitalisation; endotracheal intubation in the delivery room or outside the delivery room during hospitalisation; surfactant administration in the delivery room or during hospital admission; rate of mechanical ventilation; chronic lung disease; air leaks; and cranial ultrasound abnormalities.

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from RCTs as high quality but downgraded evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations on the basis of the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of evidence, precision of estimates, and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create a ‘Summary of findings’ table to report the quality of evidence.

The GRADE approach yields an assessment of the quality of a body of evidence according to one of four grades.

-

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

-

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

-

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

-

Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Results

Description of studies

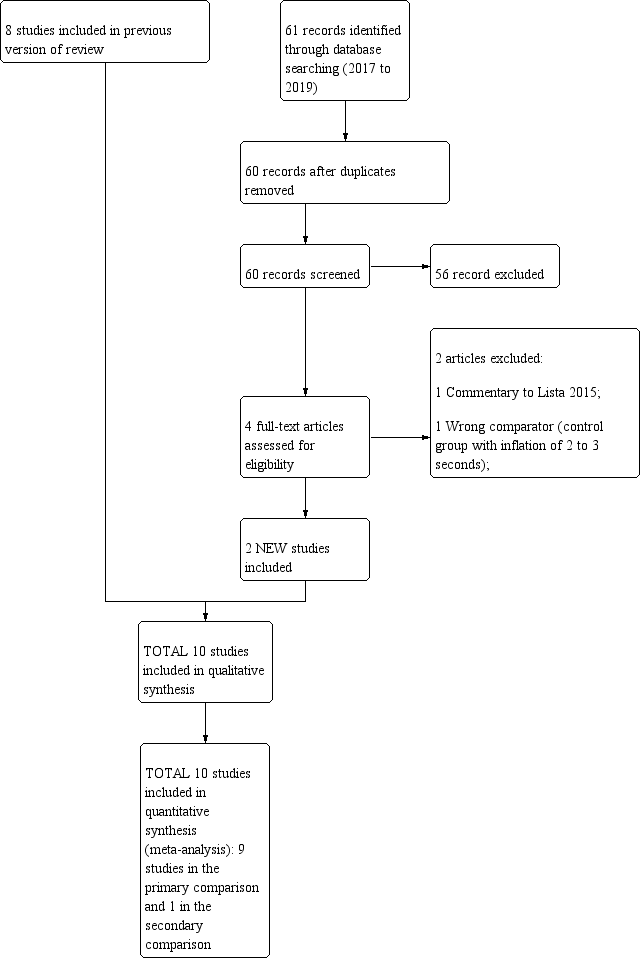

We have provided results of the search for this review update in the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

Study flow diagram: review update.

Results of the search

See summary of findings Table for the main comparison, summary of findings Table 2, Characteristics of included studies,Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies sections for details.

Included studies

Ten trials that recruited 1467 infants (768 in SLI groups, 699 in control groups) met the inclusion criteria (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2018; Schwaberger 2015). We pooled nine trials (with 1458 infants) in the comparison of the use of initial sustained inflation versus standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions (Comparison 1) (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015; see summary of findings Table for the main comparison). In contrast to other trials, Schwaberger 2015 sought to use near‐infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to investigate whether SLI affected physiological changes in cerebral blood volume and oxygenation.

We could not perform any meta‐analysis in the comparison of the use of initial sustained inflation versus standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions because we identified only one trial for inclusion (a pilot study of 9 preterm infants) (Schmölzer 2018, see summary of findings Table 2).

We have listed characteristics of populations and interventions and comparisons of the 10 trials under Characteristics of included studies and in Table 1.

| Trial (no. infants) | Antenatal steroids | Gestational age, weeks | Birth weight, grams | Device/Interface | Interventions/Controls | ||||

| SLI | Control | SLI | Control | SLI | Control | SLI and control | SLI | Control | |

| Abd 2017 (100) | 70% to 80% | 55% | 29.3 to 29.7 | 29.4 (SD 2.1) | 1363 to 1367 | mean 1249 (SD 363) | T‐piece | 4 different arms: PIP of either 15 or 20 cmH₂O for either 10 or 20 seconds | PEEP 5 cmH₂O, oxygen 30% |

| El‐Chimi 2017 (112) | 39% | 34.5% | mean 31.1 (SD 1.7) | mean 31.3 (SD 1.7) | mean 1561 (SD 326) | mean 1510 (SD 319) | Mask and T‐piece in SLI group Mask and self‐inflating bag with an oxygen reservoir in control group | PIP of 20 cmH₂O for 15 seconds, followed by PEEP of 5 cmH₂O If needed: a second SLI of 15 seconds of 25 cmH₂O for 15 seconds, followed by PEEP of 6 cmH₂O; then a third SLI of 15 seconds of 30 cmH₂O for 15 seconds, followed by PEEP of 7 cmH₂O If still not satisfactory: intubated in delivery room | PIP maximum 40 cmH₂O, rate of 40 to 60 breaths/min for 30 seconds |

| Jiravisitkul 2017 (81) | 63% | 74% | 25 to 28 weeks: 29 to 32 weeks: | 25 to 28 weeks: 29 to 32 weeks: | mean 1206 (SD 367) | mean 1160 (SD 411) | Mask and T‐piece | PIP of 25 cmH₂O for 15 seconds If HR 60 to 100 beats/min and/or poor respiratory effort: a second SLI (25 cmH₂O, 15 seconds) | PIP 15 to 20 cmH₂O, PEEP 5 cmH₂O for 30 seconds, followed by resuscitation according to AHA guidelines |

| Kirpalani 2019 (426) | 97% | 97% | 23 to 24 weeks: n = 76; 25 to 26 weeks: | 23 to 24 weeks: n = 75; 25 to 26 weeks: | median 725 (IQR 620 to 855) | median 731 (IQR 630 to 854) | Either mask or a nasopharyngeal tube (as unit protocol dictated) and T‐piece resuscitator | PIP of 20 cmH₂O for 15 seconds. If needed: a second SLI of 15 seconds of 25 cmH₂O | PIP with PEEP |

| Lindner 2005 (61) | 81% | 80% | median 27.0 (IQR 25.0 to 28.9) | median 26.7 (IQR 25.0 to 28.9) | median 870 (IQR 410 to 1320) | median 830 (IQR 370 to 1370) | Nasopharyngeal tube (fixed at 4 to 5 cm) and mechanical ventilator | PIP of 20 cmH₂O for 15 seconds If response was not satisfactory: 2 further SLIs of 15 seconds (25 and 30 cmH₂O). Then PEEP at 4 to 6 cmH₂O | PIP 20 cmH₂O, PEEP 4 to 6 cmH₂O; inflation time 0.5 seconds; inflation rate 60 per min. Then, PEEP at 4 to 6 cmH₂O |

| Lista 2015 (301) | 87% | 91% | mean 26.8 (SD 1.2); 25 to 26 weeks: 27 to 28 weeks: | mean 26.8 (SD 1.1); 25 to 26 weeks: 27 to 28 weeks: | mean 894 (SD 247) | mean 893 (SD 241) | Mask and T‐piece | PIP 25 cmH₂O for 15 seconds. Then reduced to PEEP of 5 cmH₂O | PEEP 5 cmH₂O, followed by resuscitation according to AHA guidelines |

| Mercadante 2016 (185) | 40% | 32% | mean 35.2 (SD 0.8) | mean 35.2 (SD 0.8) | mean 2345 (SD 397) | mean 2346 (SD 359) | Mask and T‐piece | PIP 25 cmH₂O for 15 seconds, followed by PEEP of 5 cmH₂O. In case of persistent heart failure (HR < 100 bpm): SLI repeated | PEEP 5 cmH₂O, followed by resuscitation according to AAP guidelines |

| Ngan 2017 (162) | 78% | 70% | mean 28 (SD 2.5) | mean 28 (SD 2.5) | mean 1154 (SD 426) | mean 1140 (SD 406) | Mask and T‐piece | Two PIPs of 24 cmH₂O. Duration of first SLI was 20 seconds. Duration of second SLI was 20 or 10 seconds, guided by ECO₂ values. After SLIs, CPAP if breathing spontaneously or, if found to have apnoea or laboured breathing, mask IPPV at a rate of 40 to 60 bpm | IPPV, rate of 40 to 60 inflations/min until spontaneous breathing, at which time CPAP will be provided |

| Schmölzer 2018 (9) | 80%a | 100%a | mean 24.6 (SD 1.3)a | mean 25.6 (SD 2.3)a | mean 707 (SD 208)a | mean 808 (SD 192)a | Mask and T‐piecea | PIP for 20 + 20 secondsa during chest compressions | 3:1 compression:ventilation ratio according to resuscitation guidelines |

| Schwaberger 2015 (40) | not reported | not reported | mean 32.1 (SD 1.4) | mean 32.1 (SD 1.6) | mean 1692 (SD 297) | mean 1722 (SD 604) | Mask and T‐piece | PIP 30 cmH₂O for 15 seconds, to be repeated once or twice with HR remaining < 100 bpm. Infants with HR > 100 bpm: PPV at 30 cmH₂O PIP or CPAP at PEEP level of 5 cmH₂O depending on respiratory rate | Resuscitation according to AHA guidelines PEEP 5 cmH₂O if respiratory rate > 30 and signs of respiratory distress PPV at 30 cmH₂O PIP if insufficient breathing efforts |

aInformation provided by study authors

Settings and populations

Researchers conducted the included studies on five different continents: two in Italy (Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016); two in Canada by the same contact author (Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2018); two in Egypt (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017); one in Germany (Lindner 2005); one in Austria (Schwaberger 2015); one in Thailand (Jiravisitkul 2017); and one international multicentre (Kirpalani 2019) conducted in 18 neonatal intensive care units in nine countries (USA, Australia, the Netherlands, Canada, Germany, Italy, Austria, South Korea, and Singapore). Two studies were conducted at multiple centres (Kirpalani 2019; Lista 2015). Six of the 10 trials included infants with mean birth weight of more than 1 kg (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015), whereas three included studies enrolled extremely low birth weight infants (Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015), as did the pilot trial (Schmölzer 2018). Mercadante 2016 was the only trial conducted in late preterm infants. No trials enrolled full‐term infants. Table 1 shows additional information on populations.

Interventions

Trials pooled in Comparison one (i.e. without chest compressions) reported that peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) was sustained for 15 seconds in seven trials (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015); and for 20 seconds in Ngan 2017. However, levels of PIP ranged from 20 cmH₂O (El‐Chimi 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005) to 24 (Ngan 2017), 25 (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016), and 30 cmH₂O (Schwaberger 2015). Investigators provided additional SLIs in cases of poor response, with the same (Jiravisitkul 2017; Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015) or higher PIP (El‐Chimi 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005); researchers in Ngan 2017 based the duration of the second SLI on exhaled CO₂ values. One study consisted of five groups: PIP of either 15 or 20 cmH₂O for either 10 or 20 seconds; control arm with PEEP 5 cmH₂O, oxygen 30% (Abd 2017). As regards interface and ventilation devices, most included trials used mask and T‐piece. Lindner 2005 used nasopharyngeal tube and ventilator, however, and El‐Chimi 2017 introduced a relevant bias into the study design by using a T‐piece ventilator in the SLI group and a self‐inflating bag in the control group (mask in both SLI and control groups). No trials reported whether prespecified levels of pressure for the SLI were actually delivered according to the protocol. Study authors did not monitor leaks at the mask and lung volumes during the manoeuvre. Whether the infant breathed before or during the SLI was not recorded: apnoeic newborns at birth are known to show less gain in lung volume during an SLI than actively breathing infants (Lista 2017).

For Comparison 2, in which infants in both SLI and control groups were resuscitated with chest compressions, duration of SLI was 20 + 20 seconds (Schmölzer 2018).

Table 1 shows additional information on interventions.

Excluded studies

We have summarised the reasons for exclusion of potentially eligible trials in the Characteristics of excluded studies table (Bouziri 2011; Gupta 2017; Harling 2005; Hunt 2019; te Pas 2007).

In particular, we excluded te Pas 2007 because sustained inflation was only one element of the intervention, and because it is not possible to determine the relative contributions of various elements of this intervention to differences observed between groups. We excluded Harling 2005, as investigators randomised infants in this trial to receive inflation for 2 seconds or 5 seconds at initiation of PPV. Similarly, in Hunt 2019 the duration of inflation in the control group was 2 to 3 seconds. All infants thus received sustained (> 1 second) inflations as defined in our protocol (O'Donnell 2004).

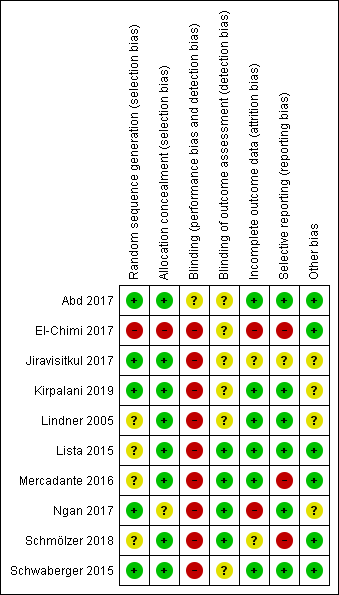

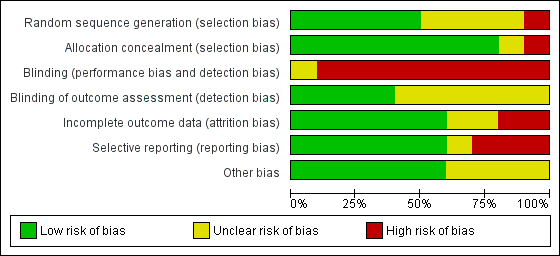

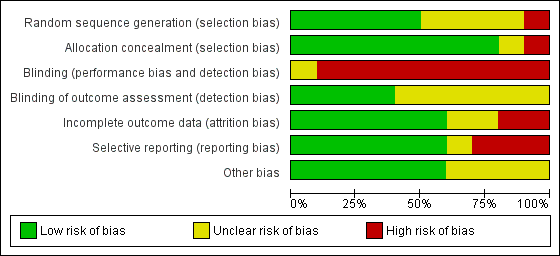

Risk of bias in included studies

We have presented a summary of the 'Risk of bias' assessment in Figure 2 and Figure 3. We have provided details of the methodological quality of included trials in the Characteristics of included studies section.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included trial.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials.

Allocation

One trial had high risk of selection bias: This quasi‐randomised trial (odd‐numbered sheets indicated allocation to the SLI group, and even‐numbered sheets to the control group) did not use opaque envelopes (information provided by study authors) (El‐Chimi 2017). In Abd 2017, Kirpalani 2019, Jiravisitkul 2017 and Schwaberger 2015, risk of selection bias was low as regards random sequence generation and allocation concealment (opaque, numbered envelopes). In Ngan 2017, risk of selection bias was low as regards random sequence generation and was unclear for allocation concealment: timing of randomisation resulted in many post‐randomisation exclusions, as results showed more post‐randomisation exclusions in the SLI group than in the control group. In the other four trials, risk of selection bias was unclear as regards random sequence generation and was low as regards allocation concealment (opaque, numbered envelopes) (Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Schmölzer 2018).

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention, all trials were unblinded, leading to high risk of performance bias. However, five trials blinded researchers assessing trial endpoints to the nature of study treatments (Kirpalani 2019; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2018). Furthermore it should be considered that blinding does not affect mortality. This outcome was considered by all included primary studies, limiting the risk of dealing with spurious or biased findings.

Incomplete outcome data

El‐Chimi 2017 transferred almost half of enrolled infants to other NICUs; we excluded this study from analysis owing to the high rate of follow‐up, although the primary outcome of the study (treatment failure/success within 72 hours) could have been determined and reported for all randomised infants. In Ngan 2017, post‐randomisation exclusion (27%) resulted in fewer included infants in the SLI group. Most trials accounted for all outcomes (Abd 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015).

Selective reporting

Six trials provided complete results for all planned outcomes (Abd 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015).

Other potential sources of bias

El‐Chimi 2017 and Schwaberger 2015 did not report sample size calculations. For Schwaberger 2015, investigators registered the protocol after study initiation. Jiravisitkul 2017 planned sample sizes of 40 infants for each group but allocated only 38 to the control group. Lindner 2005 was stopped after the interim analysis. It was unclear why study authors made this decision. In Kirpalani 2019 the DSMB halted the trial for harm when 426 infants had been enrolled (of a planned sample size of 600). Ngan 2017 did not achieve the planned sample size; in addition, the incidence of the primary outcome in the control group was less than that assumed for the sample size calculation, leading to lack of power to detect the chosen effect size. The other trials appear free of other bias.

We did not explore possible bias through generation of funnel plots because fewer than 10 trials met the inclusion criteria of this Cochrane Review.

Effects of interventions

See: Summary of findings for the main comparison Use of initial sustained inflation compared to standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions for; Summary of findings 2 Use of initial sustained inflation for

Comparison 1: use of initial sustained inflation versus standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions

Nine trials (with 1458 infants) are included in the comparison of the use of initial sustained inflation versus standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions (Comparison 1) (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015) (see summary of findings Table for the main comparison).

Primary outcomes

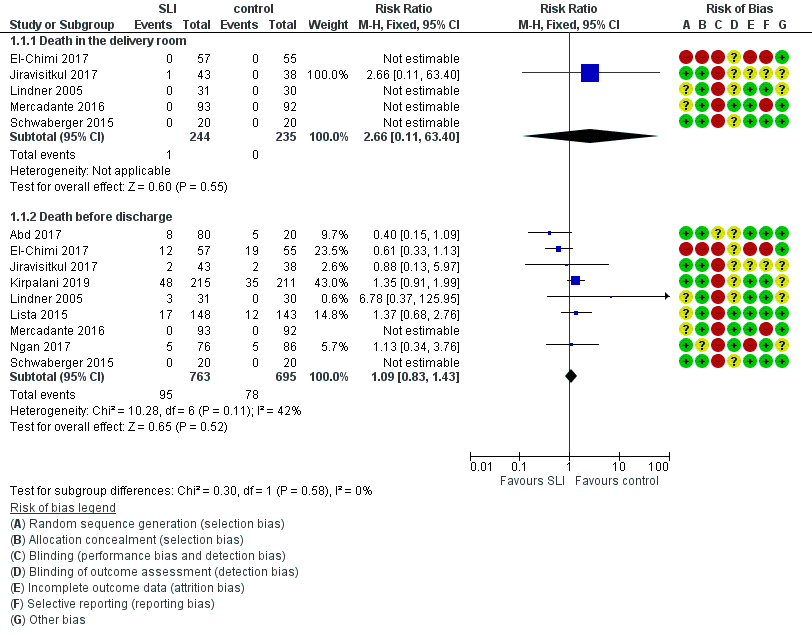

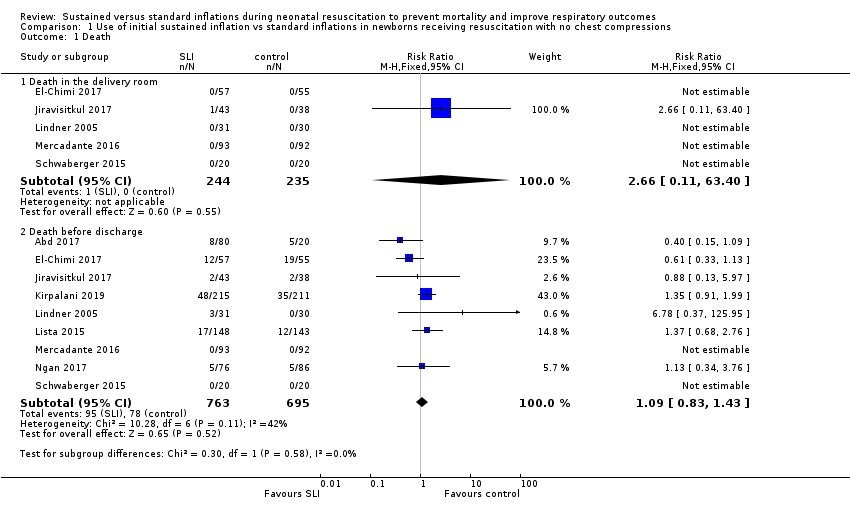

Death (Outcome 1.1)

Death in the delivery room (Outcome 1.1.1)

Five trials (N = 479) reported this outcome (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Schwaberger 2015); only one event occurred across both arms (death caused by severe birth asphyxia as the result of a prolapsed cord in the SLI group in Jiravisitkul 2017) (typical RR 2.66, 95% CI 0.11 to 63.40; typical RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.02; I² not applicable for RR and I² = 0% for RD; 5 studies, 479 participants) (Analysis 1.1 and Figure 4). The quality of the evidence (GRADE) for this outcome was low due to limitations in study design and imprecision (see summary of findings Table for the main comparison). For two trials we obtained mortality data from trial authors (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005).

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions ‒ Outcome: 1.1 Death.

Death during hospitalisation (Outcome 1.1.2)

The observed death rate increased with longer follow‐up. All trials reported mortality during hospitalisation (typical RR 1.09, 95% 0.83 to 1.43; typical RD 0.01, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.04; I² = 42% for RR and I² = 24% for RD; 9 studies, 1458 participants; observed deaths = 143) (Analysis 1.1 and Figure 4) (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). The quality of the evidence (GRADE) for this outcome was moderate due to limitations in study design (see summary of findings Table for the main comparison). For three trials we obtained data from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005).

In El‐Chimi 2017, 12 and 19 infants died in SLI and control groups, respectively. In Jiravisitkul 2017, two infants in each group died: in the SLI group, one died of severe birth asphyxia as the result of a prolapsed cord, and the other died at three hours of life of suspected umbilical catheter migration with haemothorax; in the control group, one died of severe respiratory distress syndrome at two hours of life, and the other of septic shock at 168 days of life. In Lindner 2005, three deaths occurred in the sustained inflation group: at day 1 (respiratory failure), at day 36 (necrotising enterocolitis), and at day 107 (liver fibrosis of unknown origin). In Lista 2015, 12 infants in the control group and 17 in the sustained inflations group died during the trial. Mercadante 2016 and Schwaberger 2015 reported no events. Kirpalani 2019 was stopped earlier than planned because of increased early mortality (before 48 hours) in the SLI group. Of the 19 early deaths, 13 were in the lower gestational age stratum, with the predominant cause being assigned as cardiorespiratory failure (respiratory failure, 5; asphyxia or failed transition, 4; pulmonary hypertension, 2; haemorrhagic shock, 1; and pneumothorax, 1). Only 8 of 19 (42.1%) of those who had an early death survived long enough for a head ultrasound. Of these three (37.5%) had an intraventricular haemorrhage, one of whom also had a catastrophic gastrointestinal perforation. There were three cases of sepsis.

Death to latest follow‐up

No data were provided in addition to those already presented for death during hospitalisation (Analysis 1.1).

Secondary outcomes

Heart rate at 5 minutes (Outcome 1.1)

One trial (N = 426) reported on heart rate after the first resuscitation manoeuvre (Kirpalani 2019). Heart rate was more frequently low in the SLI group, with heart rate of less than 60 beats per minute (BPM) occurring in 23% and 11% of the infants in the SLI and control group, respectively, whereas heart rate was greater than 100 BPM in 25% and 41% of the infants in the SLI and control group, respectively (P < 0.001).

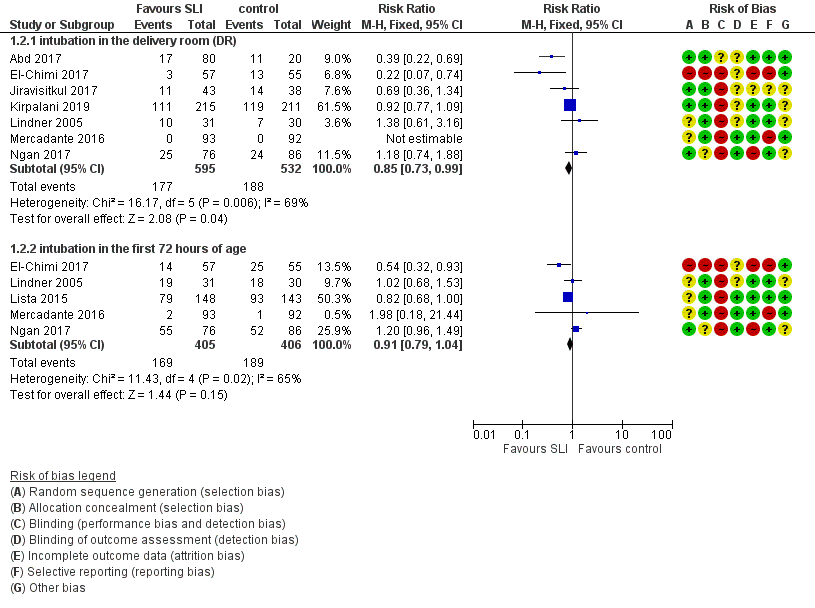

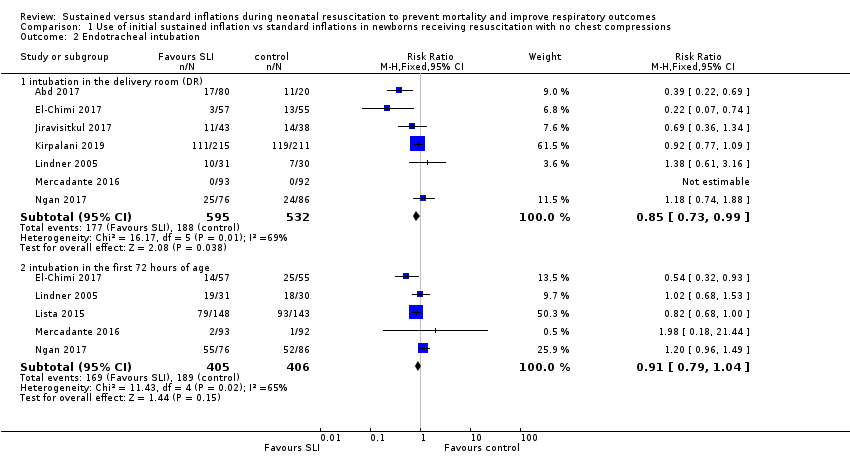

Endotracheal intubation (Outcome 1.2)

Endotracheal intubation in the delivery room (Outcome 1.2.1)

Seven trials (N = 1127) reported this outcome (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017). Rate of endotracheal intubation in the delivery room was lower in SLI group (typical RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.99; typical RD −0.05, 95% CI −0.10 to −0.00; I² = 69% for RR and I² = 84% for RD; 7 studies, 1127 participants) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 5). Heterogeneity was moderate (I² = 69%) for RR and high for RD (I² = 84%). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Mercadante 2016).

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions ‒ Outcome: 1.4 Endotracheal intubation.

Endotracheal intubation in the first 72 hours of life (Outcome 1.2.2)

Five included trials (N = 811) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.04; typical RD −0.04, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.01; I² = 65% for RR and I² = 79% for RD; 5 studies, 811 participants) (Analysis 1.2; Figure 5) (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016).

Surfactant administration (Outcome 1.3)

Surfactant administration in the delivery room (Outcome 1.3.1)

Four trials (N = 761) reported this outcome (typical RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.27; typical RD 0.02, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.08; I² = 0 % for RR and RD; 4 studies, 761 participants) (Analysis 1.3; Figure 6) (El‐Chimi 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Ngan 2017). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017).

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Use of initial sustained inflation vs standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with no chest compressions ‒ Outcome: 1.5 Surfactant administration.

Surfactant administration during hospital admission (Outcome 1.3.2)

All trials included in Comparison 1 (N = 1458) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.08; typical RD −0.00, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.04; I² = 0% for RR and RD; 9 studies, 1458 participants) (Analysis 1.3; Figure 6) (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016).

Rate of mechanical ventilation (Outcome 1.4)

Four trials (N = 910) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.02; typical RD −0.05, 95% CI −0.11 to 0.01; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 69% for RD; 4 studies, 910 participants) (Analysis 1.4) (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lista 2015). The quality of the evidence (GRADE) for this outcome was moderate due to limitations in study design (see summary of findings Table for the main comparison). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (El‐Chimi 2017).

Duration of nasal continuous airway pressure (Outcome 1.5)

Three trials (N = 355) reported this outcome (MD 0.26 days, 95% CI −0.19 to 0.72; I² = 59%; 3 studies, 355 participants) (Analysis 1.5) (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors; data for this outcome refer to survivors at time of assessment (El‐Chimi 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016).

Duration of ventilation via an ETT (Outcome 1.6)

Five trials (N = 524) reported this outcome (MD −5.37 days, 95% CI −6.31 to −4.43; I² = 95%; 5 studies, 524 participants) (Analysis 1.6) (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). Data for this outcome refer to survivors at time of assessment (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Jiravisitkul 2017; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). Heterogeneity, statistical significance, and magnitude of effects of this outcome are largely influenced by a single study (Ngan 2017): when this study was removed from the analysis, the size of the effect was reduced (MD −1.71 days, 95% CI −3.04 to −0.39; I² = 0%). In Ngan 2017, a second SLI was delivered to 84% of the infants in the SLI group and was guided by the amount of ECO₂.

Duration of respiratory support (nasal continuous airway pressure and ventilation via an ETT, considered in total) (Outcome 1.7)

Two trials (N = 243) reported this outcome (MD 0.69 days, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.16; 2 studies, 243 participants; I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.7) (Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors; data refer to survivors at time of assessment (Lindner 2005; Mercadante 2016). Abd 2017 provided medians and interquartile range and observed significantly shorter times in the conventional group: 7.5 days (4 to 13.75 days) in SLI groups vs 2 (1 to 4.25 Days) in control group (P < 0.01).

Duration of supplemental oxygen requirement (days) (Outcome 1.8)

One trial (N = 81) reported this outcome (MD −9.73, 95% CI −25.06 to 5.60; 1 study, 81 participants) (Analysis 1.8) (Jiravisitkul 2017). The test for heterogeneity was not applicable. We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Jiravisitkul 2017). Abd 2017 provided medians and interquartile range: 6 days (2 to 15 days) in SLI groups vs 4 (0 to 6.5 Days) in control group.

Chronic lung disease (i.e. rate of supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks of gestational age for infants born at or before 32 weeks of gestation) (Outcome 1.9)

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) any grade (Outcome 1.9.1)

Four trials (N = 735) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.18; typical RD −0.00, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.07; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 0% for RD; 4 studies, 735 participants) (Abd 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Ngan 2017). The quality of the evidence (GRADE) for this outcome was moderate due to limitations in study design (see summary of findings Table for the main comparison). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors; data refer to survivors at time of assessment (Lindner 2005)(Analysis 1.9).

Moderate to severe BPD (Outcome 1.9.2)

Five included trials (N = 683) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.22; typical RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.05; I² = 47% for RR and I² = 57% for RD; 5 studies, 683 participants) (Analysis 1.9) (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). The quality of the evidence (GRADE) for this outcome was moderate due to limitations in study design (see summary of findings Table for the main comparison).

Air leaks (pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, pulmonary interstitial emphysema) reported individually or as a composite outcome (Outcome 1.10)

Pneumothorax in first 48 hours of life (Outcome 1.10.1)

One trial (N = 81) reported this outcome (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.06 to 13.65; RD −0.00, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.06) (Jiravisitkul 2017). The test for heterogeneity was not applicable (Analysis 1.10).

Pneumothorax at any time (Outcome 1.10.2)

Eight included studies (N = 1377) reported this outcome (typical (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.40; typical RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.02; I² = 34% for RR and I² = 49% for RD; 8 studies, 1377 participants) (Analysis 1.10) (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). The quality of the evidence (GRADE) for this outcome was low due to limitations in study design and imprecision (see summary of findings Table for the main comparison).

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (Outcome 1.11)

One trial (N = 426) reported this outcome (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.39 to 3.35; RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.03 to 0.04). The test for heterogeneity was not applicable (Analysis 1.11) (Kirpalani 2019).

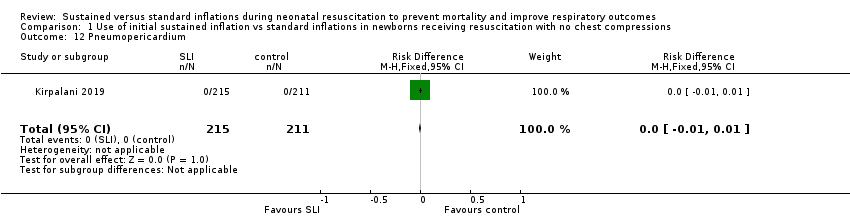

Pneumopericardium (Outcome 1.12)

One trial (N = 426) reported this outcome. No events were observed (Kirpalani 2019).

Cranial ultrasound abnormalities (Outcome 1.13)

Intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), grade 3 or 4 according to the Papile classification (Papile 1978) (Outcome 1.13.1)

Six included trials (N = 735) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.28; typical RD −0.02, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.03; I² = 22% for RR and I² = 0% for RD; 6 studies, 735 participants) (Analysis 1.13) (Abd 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). The quality of the evidence (GRADE) for this outcome was low due to limitations in study design and imprecision (see summary of findings Table for the main comparison).

IVH any grade (Outcome 1.13.2)

Three included trials (N = 578) reported this outcome (typical RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.32; typical RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.07; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 0% for RD; 3 studies, 578 participants) (Analysis 1.13) (El‐Chimi 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Schwaberger 2015).

Cystic periventricular leukomalacia (Outcome 1.13.3)

Five included trials (N = 635) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.44; typical RD −0.04, 95% CI −0.04 to 0.01; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 0% for RD; 5 studies, 635 infants) (Analysis 1.13) (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015).

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) ≥ stage 3 (Outcome 1.14)

Six trials (N = 732) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.15; typical RD −0.03, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.01; I² = 30% for RR and I² = 51% for RD; 6 studies, 732 participants; Analysis 1.14) (Abd 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). For Lindner 2005, data refer to survivors at time of assessment; and for Abd 2017, data refer to pre‐threshold values. Kirpalani 2019 reports data ROP of any grade: 99/196 (50.5%) in SLI group vs 97/182 (53.3%) in conventional group (Analysis 1.14).

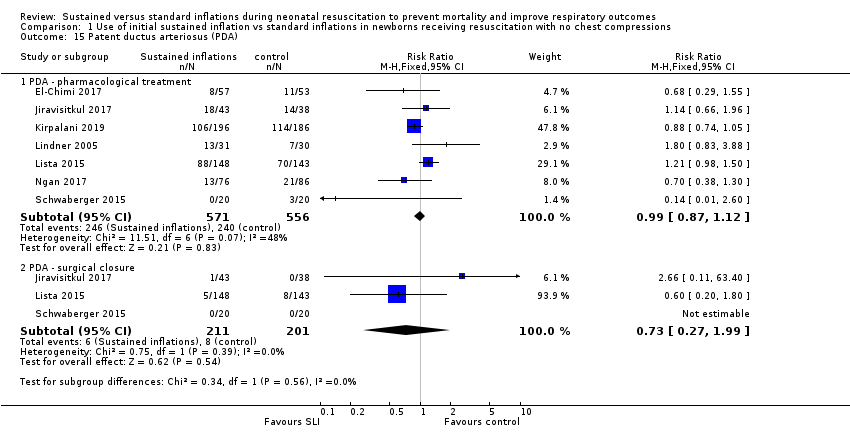

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (Outcome 1.15)

Rate of PDA ‒ pharmacological treatment (Outcome 1.15.1)

Seven included trials (N = 1127) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.12; typical RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.05; I² = 48% for RR and I² = 53% for RD; 7 studies, 1127 participants; Analysis 1.15) (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Ngan 2017; Schwaberger 2015). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schwaberger 2015).

One trial reported PDA rates (2/80 vs 2/20) without specifying whether requiring pharmacological or surgical treatment, and therefore they could not be added to the meta‐analysis (Abd 2017).

Rate of PDA ‒ surgical closure (Outcome 1.15.2)

Three trials (N = 412) reported this outcome (typical RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.99; typical RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.03; I² = 0% for RR and I² = 26% for RD; 3 studies, 412 infants; Analysis 1.15) (Jiravisitkul 2017; Lista 2015; Schwaberger 2015). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schwaberger 2015).

The data refer to all randomised infants, unless otherwise specified.

No data were reported for the following outcomes: heart rate; rate of supplemental oxygen at 28 days of life; seizures including clinical and electroencephalographic; hypoxic‐ischaemic encephalopathy in term and late preterm infants (grade 1 to 3) (Sarnat 1976); and long‐term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Subgroup analysis for Comparison 1

For Comparison 1, we were unable to conduct any of the four prespecified subgroup analyses for the following reasons.

-

No term infants were included.

-

For ventilation devices, all trials used a T‐piece except Lindner 2005 (mechanical ventilator). We did not perform a separate analysis because of the very small sample size and the presence of high or unclear risk of bias in most GRADE domains. Moreover, El‐Chimi 2017 used a T‐piece ventilator in the SLI group and a self‐inflating bag in the control group, thus we could not include this as a subgroup.

-

For interface, all trials used a face mask, except Lindner 2005 (nasopharyngeal tube). As for ventilation devices, we did not perform a separate analysis for Lindner 2005.

-

No trials used SLI < 5 seconds.

Comparison 2: use of initial sustained inflation versus standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions

We could not perform any meta‐analysis in the comparison of the use of initial sustained inflation versus standard inflations in newborns receiving resuscitation with chest compressions because we identified only one trial for inclusion (a pilot study of nine preterm infants) (Schmölzer 2018) (see summary of findings Table 2).

Primary outcomes

Death (Outcome 2.1)

Death in the delivery room (Outcome 2.1.1)

The included trial (N = 9) did not report this outcome (Schmölzer 2018).

Death during hospitalisation (Outcome 2.1.2)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 4.17, 95% CI 0.25 to 68.16; RD 0.40, 95% CI −0.07 to 0.87); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2018) (Analysis 2.1).

Secondary outcomes

Endotracheal intubation in the delivery room (Outcome 2.2)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.46; RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.34 to 0.34); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2018) (Analysis 2.2). We obtained data for this outcome directly from trial authors (Schmölzer 2018).

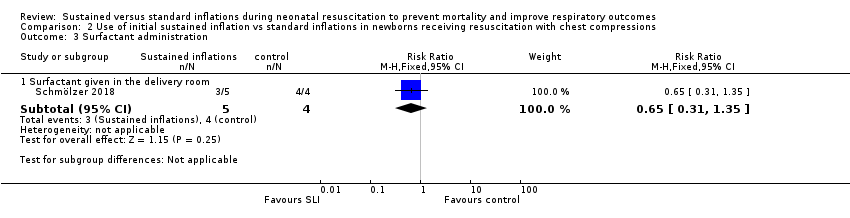

Surfactant administration in the delivery room (Outcome 2.3)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.35; RD −0.40, 95% CI −0.87 to 0.07); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2018) (Analysis 2.3).

Chronic lung disease (2.4)

Moderate to severe BDP (Outcome 2.4.1)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.37; RD −0.08, 95% CI −0.76 to 0.60); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2018) (Analysis 2.4).

Pneumothorax at any time (Outcome 2.5)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome: no events occurred (Analysis 2.5).

Cranial ultrasound abnormalities (Outcome 2.6)

Intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), grade 3 or 4 according to the Papile classification (Papile 1978) (Outcome 2.6.1)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.05 to 2.98; RD −0.30, 95% CI −0.90 to 0.30); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2018) (Analysis 2.6).

IVH any grade (Outcome 2.6.2)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.15; RD −0.80, 95% CI −1.23 to −0.37); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2018) (Analysis 2.6).

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) ≥ stage 3 (Outcome 2.7)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.68; RD −0.55, 95% CI −1.10 to 0.00); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2018) (Analysis 2.7).

Rate of PDA ‒ pharmacological treatment (Outcome 2.8)

One trial (N = 9) reported this outcome (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.25; RD −0.60, 95% CI −1.07 to −0.13); thus, the test for heterogeneity was not applicable for this outcome (Schmölzer 2018) (Analysis 2.8).

For Comparison 2, investigators provided no data on other prespecified outcomes.

Subgroup analysis for the Comparison two

For Comparison 2, we were unable to conduct any subgroup analysis as we included only one trial.

Discusión

Resumen de los resultados principales

Se evaluaron los efectos beneficiosos y perjudiciales de la insuflación pulmonar sostenida (IPS) versus la ventilación intermitente en lactantes que requieren reanimación y estabilización al nacer. Diez ensayos en los que participaron 1467 lactantes prematuros compararon las intervenciones de interés (Abd 2017 El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019 Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2018; Schwaberger 2015), con una excepción. Schmölzer 2018 no se incluyó en el metanálisis con los otros estudios porque los investigadores consideraron como intervención experimental las compresiones torácicas en combinación con la IPS.

La insuflación pulmonar sostenida no fue mejor que la ventilación intermitente para reducir la mortalidad, el resultado principal de esta revisión. La calidad de la evidencia se consideró moderada (según criterios GRADE) para la muerte antes del alta (limitaciones en el diseño de estudio de la mayoría de los ensayos incluidos) y baja (según criterios GRADE) para la muerte en la sala de partos (limitaciones en el diseño de estudio e imprecisión de las estimaciones). Al considerar los resultados secundarios, como la intubación, la tasa o duración de la asistencia respiratoria, la displasia broncopulmonar o el neumotórax, no se encontró un efecto beneficioso de la IPS sobre la ventilación intermitente. La calidad de la evidencia para los resultados secundarios fue moderada (limitaciones en el diseño de la mayoría de los ensayos incluidos, según criterios GRADE) excepto para el neumotórax (calidad baja: limitaciones en el diseño de los estudios e imprecisión de las estimaciones, según criterios GRADE). La duración de la ventilación mecánica fue más corta en el grupo de IPS (calidad baja: limitaciones en el diseño de estudio e imprecisión de las estimaciones, según criterios GRADE).

Se identificaron ocho ensayos en curso.

Compleción y aplicabilidad general de las pruebas

Hasta la fecha, en diez ensayos que comparan insuflaciones sostenidas versus estándar para la reanimación inicial se han reclutado 1467 recién nacidos. Los datos disponibles no fueron suficientes para evaluar los resultados de importancia clínica, que se identificaron a priori. Los autores de los estudios no informaron sobre resultados como la duración de la necesidad de oxígeno suplementario ni resultados del desarrollo neurológico a largo plazo y no reclutaron lactantes a término. No fue posible realizar análisis de subgrupos a priori (edad gestacional, dispositivo de ventilación, interface, duración de la insuflación sostenida) para detectar efectos diferenciales debido a la escasez de ensayos incluidos. Preguntas relevantes como las siguientes siguen sin respuesta: ¿Cuál es la duración óptima de una IPS? ¿Qué nivel de presión positiva al final de la espiración (PEEP) debería seguir? ¿Cuál es la interface/dispositivo óptimo? (McCall 2016). Fue posible resumir la evidencia disponible de manera exhaustiva, ya que se obtuvo información adicional sobre el diseño del estudio y los datos de los resultados de la mayoría de los ensayos incluidos (El‐Chimi 2017; Jiravisitkul 2017; Lindner 2005; Lista 2015; Mercadante 2016; Ngan 2017; Schmölzer 2018; Schwaberger 2015) y de dos ensayos excluidos (Harling 2005; te Pas 2007). Los ocho ensayos en curso que se identificaron informaron de importantes diferencias en la elección de la edad gestacional (NCT01255826; NCT01440868; NCT02493920; NCT02858583; NCT02887924; NCT03165305; NCT03437499; NCT03518762). NCT02493920 reclutó lactantes de 25 a 36 semanas, NCT01440868 de 25 a 28 semanas, NCT01255826 de 26 a 34 semanas, NCT03518762 de 27 a 32 semanas, NCT03437499 de 28 a 30, NCT02887924 de 26 a 29 semanas, NCT02858583 recluta lactantes a término y prematuros, mientras que NCT03165305 solo recluta a lactantes a término. Estas diferencias entre las poblaciones estudiadas podrían resultar importantes, ya que en los ensayos se ha informado que la insuflación sostenida fue más eficaz en los lactantes de 28 a 30 semanas que en los de menos de 28 o más de 30 semanas de gestación (te Pas 2007).

Calidad de la evidencia

Según los criterios GRADE, la calidad general de la evidencia para los resultados clínicamente relevantes se consideró baja a moderada (véase la tabla 1, Resumen de los hallazgos para la Comparación 1). La calidad general de la evidencia para los resultados fundamentales se disminuyó debido a las limitaciones en el diseño de los estudios (es decir, sesgo de selección debido a la falta de ocultación de la asignación) y la imprecisión de los resultados (pocos eventos para la muerte en la sala de partos y amplios intervalos de confianza para el neumotórax). Además, tres ensayos no informaron sobre los cálculos del tamaño de la muestra (Abd 2017; El‐Chimi 2017; Schwaberger 2015), y cuatro no lo lograron (Jiravisitkul 2017; Kirpalani 2019; Lindner 2005; Ngan 2017). Los resultados de los estudios más pequeños están sujetos a una mayor variación de muestreo y, por lo tanto, son menos precisos. De hecho, la imprecisión se refleja en el intervalo de confianza en torno a la estimación del efecto de la intervención de cada estudio y en la ponderación que se da a los resultados de cada estudio incluido en el metaanálisis (Higgins 2011).

Sesgos potenciales en el proceso de revisión

Una limitación importante de esta revisión Cochrane es la definición de la insuflación pulmonar sostenida, ya que los ensayos utilizaron diferentes presiones, que pueden haber repercutido en los resultados de los estudios. Harling 2005 y Hunt 2019 se excluyeron porque el grupo control recibió dos y dos a tres segundos de insuflación, respectivamente, mientras que en esta revisión "sostenido" se definió como más de un segundo. Una limitación adicional consiste en el elevado número de resultados que se especificó en esta revisión, lo que da lugar a un escaso poder estadístico en la mayoría de los análisis. Debido a que un autor de la revisión (PD) también es el autor de uno de los ensayos que se incluyó (Kirpalani 2019), los otros autores de la revisión realizaron las evaluaciones de calidad de este ensayo.

Ningún ensayo fue cegado debido a la naturaleza de la intervención. Se excluyó un ensayo potencialmente pertinente porque la insuflación sostenida fue solo un elemento de la intervención (te Pas 2007), y no es posible determinar las contribuciones relativas de los diversos elementos de esta intervención a las diferencias observadas entre los grupos. Para la actualización de esta revisión en 2017, se tomó la decisión post hoc de añadir una comparación sobre la base de la presencia de compresiones torácicas durante la reanimación.

Acuerdos y desacuerdos con otros estudios o revisiones