Reparación laparoscópica para la úlcera péptica perforada

Referencias

Referencias de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios excluidos de esta revisión

Referencias adicionales

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

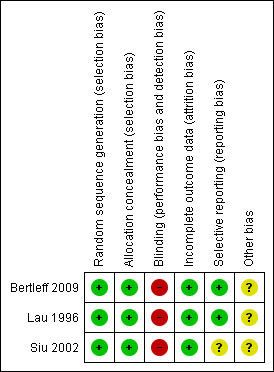

| Methods | 77 months, multicenter RCT parallel design, randomized using computer‐generated random numbers, concealment of allocation using sealed envelopes, outcome assessment was carried out by the treating team, losses to follow up not reported, intention‐to‐treat analysis | |

| Participants | 101 patients (52 for laparoscopic group and 49 for open‐surgery group). Inability to complete informed consent Prior upper abdominal surgery Current pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Intravenous antibiotics at the diagnosis, type and time not specified. All patients were allocated for Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. | |

| Outcomes | Postoperative complications | |

| Notes | Sample size was not calculated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Surgeons contacted the study coordinator" "The envelope randomisation was based on a computer‐generated list provided by the trial statistician" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomisation took place by opening a sealed envelope" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | "this was an unblinded trial" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Protocol published on the Clinicaltrials.gov website |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | In surgical trials, there is always a bias related with learning curve for the new surgical methods. However, we believe this bias is not present in this trial because the experience of surgeons is similar. In multicenter trials, a bias related with high volume and low volume centers is possible. There is no information about the number of patients by center. |

| Methods | 28 months, RCT parallel design, randomized using computer‐generated random numbers by the block method, concealment of allocation using sealed envelopes, outcome assessment was made by two assessors (not stated if independent from the treating team and blind) for pain evaluation and by the treating team for activity, work return evaluation and complications, available to follow‐up at 4 weeks: 73% for laparoscopic group versus 69% for open surgery group but all live patients available at 8 weeks for gastroscopy, to intention‐to‐treat analysis. | |

| Participants | 93 patients (48 for laparoscopic group and 45 for open surgery group). | |

| Interventions | Intravenous cefuroxime 750 mg and metronidazole 500 mg were given at the time of induction and for the first postoperative day. | |

| Outcomes | Complications | |

| Notes | Sample size was calculated using the analgesic doses using a previous study made by the same authors. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Computer‐generated blocked random numbers were used" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "to assign the type of surgery, which was written on a card sealed in a completely opaque envelope. Envelopes were drawn randomly by the senior duty nurse in the operating department" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | "All patients were assessed by the treating team approximately 4 weeks postoperatively in the outpatient clinic" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | "At the end of 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, gastroscopy showed that the ulcers had healed for all patients", "Similar proportions of patients with laparoscopic repair (group 1 and 2) and open repair (groups 3 and 4) were available at follow‐up (73% vs. 69%), respectively", "The data for patients who did not attend this first follow‐up visit but who were called back for a check‐up gastroscopy were not included in this analysis because there was a delay of at least 1 month in the recording of these data, which made it less reliable" We believe that lost to follow up at four weeks for measuring returning to work do no affect results of important outcomes for this systematic review. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported a second study in 1998 that is consistent with data from this study. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | In surgical trials, there is always a bias related with learning curve for the new surgical methods. However, we believe this bias is not present in this trial because experience of surgeons is similar. |

| Methods | 41 months, RCT parallel design, randomized using computer‐generated random numbers by the block method, concealment of allocation using sealed envelopes, outcome assessment was made by assessors independent from the treating team for pain evaluation; by independent surgeons not blinded for discharge and by the treating surgeon not blinded for activity, work return evaluation and complications, intention‐to‐treat analysis, without losses to follow up | |

| Participants | 121 patients (63 for the laparoscopic group and 58 for the open surgery group) | |

| Interventions | Intravenous cefuroxime 750 mg was given at the time of induction and continued for 5 days. | |

| Outcomes | Complications | |

| Notes | Sample size was calculated using the analgesic dose data in a previous study by the authors. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomization was performed after the decision was made for surgery; it took place in the operating room control room by a person not otherwise involved in the clinical setting", "computer‐generated random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomization was undertaken by consecutively numbered opaque sealed envelopes containing the treatment options" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | "An independent assessor visited every patient in the morning to record the clinical progress, analgesic requirements, and pain score", "Patients were assessed by independent surgeons for discharge if they could tolerate a normal diet, could fully ambulate, and required only oral analgesics. Both the independent assessor and in‐charge surgeons were not blinded with respect to study groups." Blinding probably do not affect the assessment of hard outcomes as surgical complications, but it is possible that length of stay and pain assessment could be biased by non blinding evaluation of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | There were no losses to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Although there is no other information in the report of the trial, analysis of the article offers enough information to assume that any bias due to selective outcome reporting should not greatly affect the results. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | In surgical trials, there is always a bias related with learning curve for the new surgical methods. However, we believe this bias is not present in this trial because experience of surgeons is similar. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial | |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial | |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial | |

| No data about septic complications | |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial | |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial | |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial | |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial | |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial | |

| Prospective non‐randomized clinical trial |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

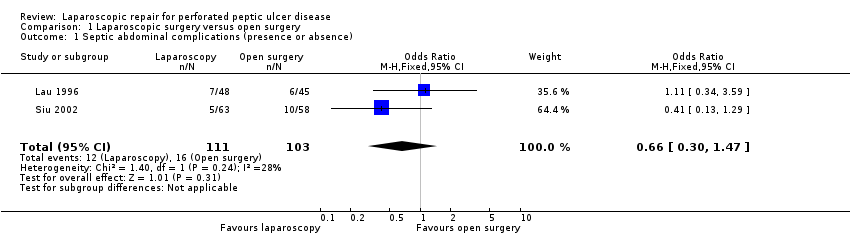

| 1 Septic abdominal complications (presence or absence) Show forest plot | 2 | 214 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.30, 1.47] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 1 Septic abdominal complications (presence or absence). | ||||

| 2 Pulmonary complications (presence or absence) Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.08, 3.55] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 2 Pulmonary complications (presence or absence). | ||||

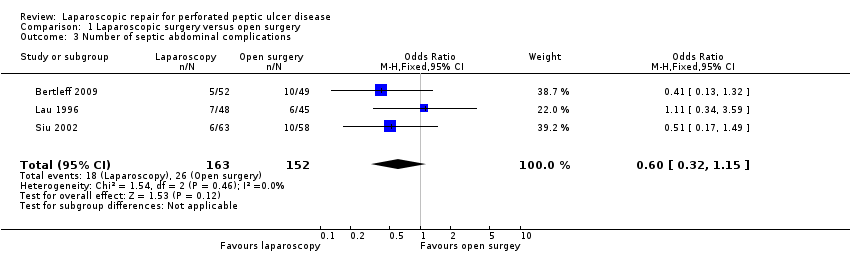

| 3 Number of septic abdominal complications Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.32, 1.15] |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 3 Number of septic abdominal complications. | ||||

| 4 Surgical site infection Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.08, 1.00] |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 4 Surgical site infection. | ||||

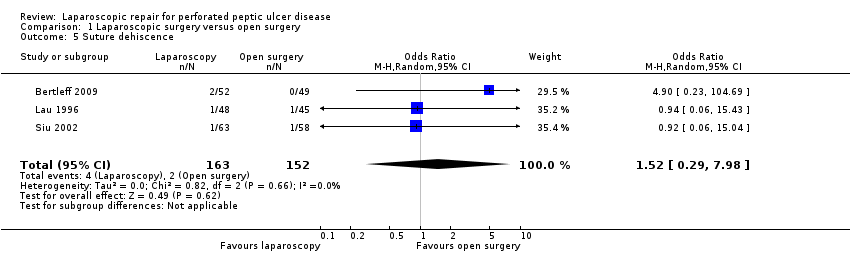

| 5 Suture dehiscence Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.29, 7.98] |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 5 Suture dehiscence. | ||||

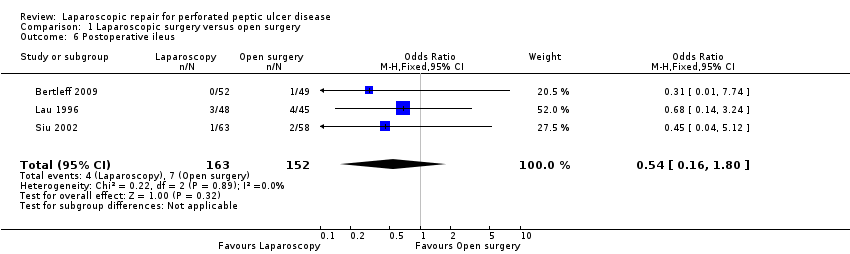

| 6 Postoperative ileus Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.16, 1.80] |

| Analysis 1.6  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 6 Postoperative ileus. | ||||

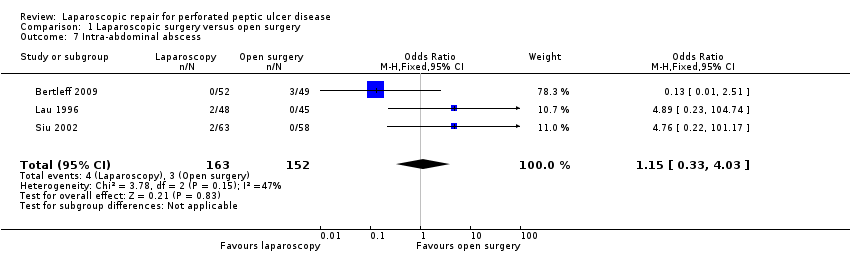

| 7 Intra‐abdominal abscess Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.33, 4.03] |

| Analysis 1.7  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 7 Intra‐abdominal abscess. | ||||

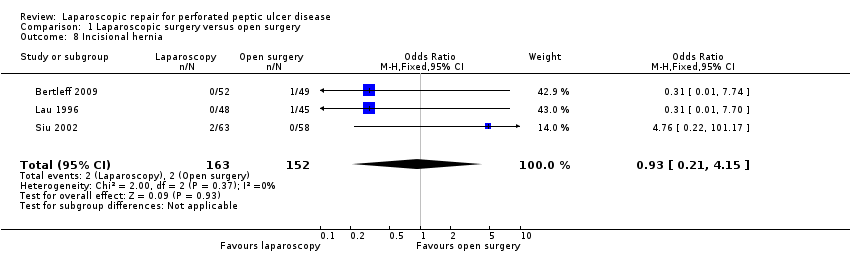

| 8 Incisional hernia Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.21, 4.15] |

| Analysis 1.8  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 8 Incisional hernia. | ||||

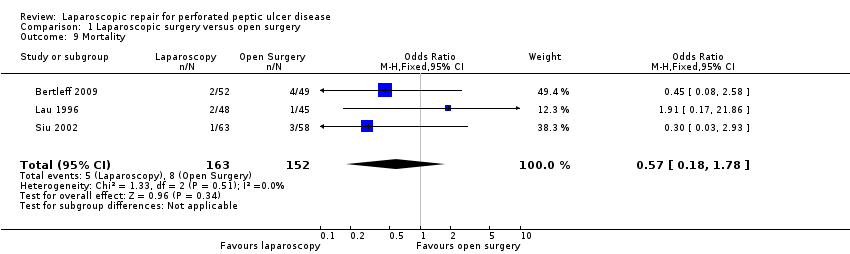

| 9 Mortality Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.18, 1.78] |

| Analysis 1.9  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 9 Mortality. | ||||

| 10 Number of reoperations Show forest plot | 2 | 214 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.89 [0.46, 7.71] |

| Analysis 1.10  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 10 Number of reoperations. | ||||

| 11 Operative time Show forest plot | 2 | 214 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 14.62 [‐35.25, 64.49] |

| Analysis 1.11  Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 11 Operative time. | ||||

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 1 Septic abdominal complications (presence or absence).

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 2 Pulmonary complications (presence or absence).

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 3 Number of septic abdominal complications.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 4 Surgical site infection.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 5 Suture dehiscence.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 6 Postoperative ileus.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 7 Intra‐abdominal abscess.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 8 Incisional hernia.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 9 Mortality.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 10 Number of reoperations.

Comparison 1 Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery, Outcome 11 Operative time.

| Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for perforated peptic ulcer disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with perforated peptic ulcer disease | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery | |||||

| Septic abdominal complications (presence or absence) | 155 per 1000 | 108 per 1000 | OR 0.66 | 214 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| Pulmonary complications (presence or absence) | 86 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 | OR 0.52 | 315 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| Surgical site infection | 72 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 | OR 0.28 | 315 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | |

| Suture dehiscence | 13 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 | OR 1.52 | 315 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| Postoperative ileus | Study population | OR 0.54 | 315 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| 46 per 1000 | 25 per 1000 | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 35 per 1000 | 19 per 1000 | |||||

| Intra‐abdominal abscess | 20 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 | OR 1.15 | 315 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | |

| Operative time | The mean operative time in the control groups was | The mean operative time in the intervention groups was | 214 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1 Imprecision is probably because the small sample size of the studies and the lack of reporting form the largest one. | ||||||

| Variable | Study | Laparoscopic group | Open surgery group | P value |

| Nasogastric aspiration time (median and range) | 2 (3.0) IQR | 3 (1.3) IQR | 0.33 | |

| 3 (2‐33) | 3(1‐8) | 0.28 | ||

| 2 (1‐4)/ 3 (2‐1) | 2 (1‐13)/ 3(1‐17) | No significant (P value not reported) | ||

| Time to return to oral diet | 4 (3‐35) | 5 (3‐24) | 0.06 | |

| 4 (3‐7)/ 4 (2‐11) | 4 (3‐16)/ 4 (3‐19) | No significant (P value not reported) | ||

| Length of stay | 6.5 (9.3) IQR | 8 (7.3) IQR | 0.23 | |

| 6 (4‐35) | 7 (4‐39) | 0.004 | ||

| 5 (3‐20)/ 6 (3‐11) | 5 (3‐19)/ 5 (2‐21) | No significant (P value not reported) | ||

| Analgesic doses | 0 (0‐11) | 6 (1‐30) | <0.001 | |

| 1 (0‐12)/ 2 (0‐17) | 3 (0‐10)/ 4 (1‐9) | 0.03 | ||

| 1 (1.25) median days of analgesics | 1 (1.0) median days of analgesics | 0.007 |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Septic abdominal complications (presence or absence) Show forest plot | 2 | 214 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.30, 1.47] |

| 2 Pulmonary complications (presence or absence) Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.08, 3.55] |

| 3 Number of septic abdominal complications Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.32, 1.15] |

| 4 Surgical site infection Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.08, 1.00] |

| 5 Suture dehiscence Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.29, 7.98] |

| 6 Postoperative ileus Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.16, 1.80] |

| 7 Intra‐abdominal abscess Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.33, 4.03] |

| 8 Incisional hernia Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.21, 4.15] |

| 9 Mortality Show forest plot | 3 | 315 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.18, 1.78] |

| 10 Number of reoperations Show forest plot | 2 | 214 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.89 [0.46, 7.71] |

| 11 Operative time Show forest plot | 2 | 214 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 14.62 [‐35.25, 64.49] |