Progestogen for preventing miscarriage

Abstract

Background

Progesterone, a female sex hormone, is known to induce secretory changes in the lining of the uterus essential for successful implantation of a fertilized egg. It has been suggested that a causative factor in many cases of miscarriage may be inadequate secretion of progesterone. Therefore, progestogens have been used, beginning in the first trimester of pregnancy, in an attempt to prevent spontaneous miscarriage.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and safety of progestogens as a preventative therapy against miscarriage.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (1 August 2013), reference lists from relevant articles, attempting to contact authors where necessary, and contacted experts in the field for unpublished works.

Selection criteria

Randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trials comparing progestogens with placebo or no treatment given in an effort to prevent miscarriage.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed trial quality and extracted data.

Main results

Fourteen trials (2158 women) are included. The meta‐analysis of all women, regardless of gravidity and number of previous miscarriages, showed no statistically significant difference in the risk of miscarriage between progestogen and placebo or no treatment groups (Peto odds ratio (Peto OR) 0.99; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 1.24) and no statistically significant difference in the incidence of adverse effect in either mother or baby.

A subgroup analysis of placebo controlled trials did not find a difference in the rate of miscarriage with the use of progestogen (10 trials, 1028 women; Peto OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.50).

In a subgroup analysis of four trials involving women who had recurrent miscarriages (three or more consecutive miscarriages; four trials, 225 women), progestogen treatment showed a statistically significant decrease in miscarriage rate compared to placebo or no treatment (Peto OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.21 to 0.72). However, these four trials were of poorer methodological quality. No statistically significant differences were found between the route of administration of progestogen (oral, intramuscular, vaginal) versus placebo or no treatment. No significant differences in the rates of preterm birth, neonatal death, or fetal genital anomalies/virilization were found between progestogen therapy versus placebo/control.

Authors' conclusions

There is no evidence to support the routine use of progestogen to prevent miscarriage in early to mid‐pregnancy. However, there seems to be evidence of benefit in women with a history of recurrent miscarriage. Treatment for these women may be warranted given the reduced rates of miscarriage in the treatment group and the finding of no statistically significant difference between treatment and control groups in rates of adverse effects suffered by either mother or baby in the available evidence. Larger trials are currently underway to inform treatment for this group of women.

PICO

Plain language summary

Progestogen for preventing miscarriage

We could not find any evidence from randomized controlled trials that progestogen beginning in the first trimester of pregnancy can generally prevent miscarriage.

Hormones called progestogens prepare the womb (uterus) to receive and support the newly fertilized egg. It has been suggested that some women who miscarry may not make enough progesterone in the early part of pregnancy, so supplementing with progesterone has been suggested as a possible way to prevent miscarriage. This review of 14 randomized controlled trials (2158 women) found no evidence that progestogens can prevent miscarriage. No difference in the incidence of adverse effects on either the mother or baby were apparent. There was evidence, however, that women who have suffered three or more miscarriages may benefit from progestogen during pregnancy. Four trials showed a decrease in miscarriage compared with placebo or no treatment in these women, however, the trials were of poorer methodological quality so these findings should be interpreted with caution. No differences were found between the route of administration of progestogen (oral, intramuscular, vaginal) verus placebo or no treatment. More trials are needed and are under way to further clarify the effects in women with multiple prior miscarriages and to further clarify any impact on fetal anomalies.

Authors' conclusions

Background

Description of the condition

The term miscarriage refers to the loss of a pregnancy prior to the fetus being viable. Vaginal bleeding during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, with or without pain, is known as threatened miscarriage. This can present with anything from spots of blood to potentially fatal shock (McBride 1991). Once dilation of the cervix has begun, miscarriage is inevitable (Lede 2005).

Ten per cent to 15% of all clinically recognized pregnancies end in miscarriage (Regan 1989), with 1% to 2% of couples suffering recurrent early losses (traditionally defined as three or more spontaneous miscarriages) (Coulam 1991). It is thought, however, that the true incidence of early spontaneous miscarriage may be much higher (Grudzinskas 1995; Howie 1995; Simpson 1991). Miscarriage is an important cause of morbidity and mortality, especially in low‐income countries (Neilson 2006).

It has been estimated that, in over half of miscarriages, a chromosomal abnormality is present (Burgoyne 1991; Szabo 1996). Other risk factors include maternal age greater than 35 years, multiple pregnancies, uterine malformations, polycystic ovaries, autoimmune factors (such as phospholipid antibodies, lupus anticoagulant and cardiolipin antibodies), genetic disorders, poorly controlled diabetes, and having had two or more miscarriages (Lede 2005). For many couples, a cause may never be found.

The occurrence of a miscarriage may induce significant emotional distress in both partners. Initial emotional numbness and denial, anxiety, shock, sense of loss, sadness, emptiness, anger, inadequacy, blame and jealousy, depression, sleep disturbance, social withdrawal, anger and marital disturbance have all been described as emotional responses to pregnancy loss (Atkin 1998; Dyregrove 1987; Vance 1991; Woods 1987).

With the development of ultrasound has come the ability to rapidly and accurately establish the viability of a pregnancy, and the technology to predict if a pregnancy is likely to continue when there is bleeding. In situations where ultrasound has been available, the care of women with threatened miscarriage has been rationalized. Attempts to maintain a pregnancy are only likely to be effective if the fetus is viable, and is without chromosomal abnormality (Lede 2005).

Description of the intervention

Progesterone and other progestogens can be given to women orally, vaginally, intramuscularly, or by other routes. Supplementing a pregnancy with progestin often begins early in pregnancy and can continue through the first trimester and beyond.

How the intervention might work

Progesterone, a female sex hormone, is known to induce secretory changes in the lining of the uterus essential for successful implantation of a fertilized egg. It is secreted chiefly by the corpus luteum, a group of cells formed in the ovary after the follicle ruptures during the release of the egg. It has been suggested that a causative factor in many cases of miscarriage may be inadequate secretion of progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and in the early weeks of pregnancy. Therefore, progestogens have been used, beginning in the first trimester of pregnancy, in an attempt to prevent spontaneous miscarriage. Their use is particularly common with assisted reproductive technologies.

A review of pregnancy rates following hormonal treatments concluded that the benefits of therapy are uncertain (Karamadian 1992). A 1989 meta‐analysis of six trials concluded that exogenous progesterone supplementation after conception does not improve pregnancy outcomes (Goldstein 1989; Regan 1989). It was concluded that low levels of progesterone in early pregnancy reflected an already failed pregnancy (Royal 2001).

Concerns have been raised that the use of progestogens, with their uterine‐relaxant properties, in women with fertilized defective ova may cause a delay in spontaneous abortion. Several reports also suggest an association between intrauterine exposure to progesterone containing drugs in the first trimester of pregnancy and genital abnormalities in male and female fetuses. The risk of hypospadias (deformities of the penis or urethra, or both), five to eight per 1000 male births in the general population, may be increased with exposure to these drugs(Briggs 2011). However, some studies do not report increased risk with exposure to these drugs and progesterone supplementation is commonly utilized in assisted reproduction settings. There are insufficient data to quantify the risk to exposed female fetuses. Due to some of these reports and the fact that the urogenital groove is fused by 16 weeks, it has been recommended that progesterone containing drugs be avoided in the first 16 weeks of pregnancy (Briggs 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

Several Cochrane Reviews have been initiated to investigate different interventions for the prevention of miscarriage (Alfirevic 2012; Bamigboye 2003; Lede 2005; Morley 2013; Porter 2006; Rumbold 2011). The aim of this updated review is to study all available data to determine the efficacy and safety of administering prophylactic progesterone in an attempt to prevent pregnancy loss.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of progestogens as a preventative therapy against miscarriage.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized or quasi‐randomized trials comparing progestogens with placebo or no treatment, given for the prevention of miscarriage, were eligible for inclusion. Cluster‐randomized trials are also eligible for inclusion, but cross‐over design trials were not eligible.

Types of participants

Women in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. No restriction was placed on the age of participants or past obstetric history.

Types of interventions

Progestogen therapy, either natural or synthetic, given prophylactically to prevent miscarriage (i.e. loss during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy) versus placebo therapy or no therapy, regardless of dose, mode of administration or treatment duration. We considered trials pertaining to administration of progestogens starting before pregnancy if treatment continued after pregnancy was confirmed.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Miscarriage

Secondary outcomes

(1) Mother

-

Severity of 'morning sickness' ‐ intensified headache, nausea, breast tenderness

-

Reported thromboembolic events

-

Depression

-

Admission to special care unit

-

Subsequent fertility

(2) Child

-

Preterm birth

-

Stillbirth

-

Neonatal death

-

Low birthweight less than 2500 g

-

Fetal genital abnormalities

-

Teratogenic effects (impairing normal fetal development)

-

Admission to special care unit

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (1 August 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

-

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

-

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

-

weekly searches of Embase;

-

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

-

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

See Appendix 1 for search methods used in previous versions of this review.

Searching other resources

We searched the citation lists of relevant publications, review articles, abstracts of scientific meetings and included studies for both published and unpublished works.

We contacted experts in the field for unpublished works.

We obtained all reports that described (or may have described) randomized controlled trials of prophylactic progestogen to prevent pregnancy loss. We did not apply any language restrictions and attempted to make to contact authors when additional information was required.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 2.

For this 2013 update, we used the following methods when assessing the reports identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2012) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

-

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

-

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

-

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

-

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

-

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

-

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

-

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

-

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

-

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

-

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

-

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomization; more than 20% missing data);

-

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

-

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

-

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

-

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

-

low risk of other bias;

-

high risk of other bias;

-

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary Peto Odds Ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

None of our outcomes have continuous data. If future updates add continuous data, we will use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardized mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomized trials

We did not include cluster‐randomized trials in this Review. In future updates, if high‐quality cluster‐randomized trials are identified, we will consider including them in the analyses along with individually‐randomized trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook Section 16.3.4 using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomized trials and individually‐randomized trials, we plan to synthesize the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomization unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomization unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomization unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials are not included as they are inappropriate to the question.

Other unit of analysis issues

If trials with more than two treatment groups are identified and included, we will assess the most appropriate way to include the data. This may be by combining groups to create a pair‐wise comparison or to select the most appropriate pair of interventions and exclude the others. No such trials were identified.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomized to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analyzed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomized minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either the T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

As there were more than 10 studies in the meta‐analysis, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots, see Figure 1. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually. As asymmetry was not suggested by a visual assessment, we did not perform exploratory analyses to investigate it further.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, outcome: 1.1 Miscarriage (all trials).

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2012). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we planned to use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful.

In this 2013 update, we used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis. If in future updates we use random‐effects meta‐analysis, the random‐effects summary will be treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted planned subgroup analyses classifying whole trials by interaction tests as described by Deeks 2001. The subgroup analyses entailed:

-

placebo controlled trials only versus trials not having placebo control;

-

women who had at least three previous consecutive miscarriages, women with at least two prior miscarriages, versus women in trials not specifying the number of prior miscarriages who present with symptoms of threatened miscarriage;

-

route of administration of progestogen: oral, intramuscular, or vaginal versus placebo;

The following outcome was used in subgroup analysis: miscarriage.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2012). We planned to report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the χ2 statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of trial quality/risk of bias. This involved analysis of trials based on low risk of bias in order to assess for any substantive difference to the overall results.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

See Characteristics of included studies tables for details on all trials identified by the search.

Included studies

Trial design characteristics

Interventions

Route of administration

Five studies administered treatment orally (El‐Zibdeh 2005; Goldzieher 1964; Klopper 1965; MacDonald 1972; Moller 1965); four administered treatment intramuscularly (IM) (Le Vine 1964; Nyboe Anderson 2002; Reijnders 1988; Shearman 1963); two used either oral or IM progestogen but did not analyze the groups separately (Berle 1980; Tognoni 1980); two administered treatment via vaginal suppositories (Gerhard 1987; Nyboe Anderson 2002); and one used progestogen pellets inserted into the gluteal muscle (Swyer 1953).

Dosage and type of progestogen

Of the studies that administered treatment orally, one study used a dose of 10 mg/day medroxyprogesterone (Goldzieher 1964), while one study used a staggered dose of medroxyprogesterone (20 mg/day for three days, followed by 10 mg/day for 11 days, then increased the dose two different times later in the study duration) (Moller 1965). One study used a twice daily dose of cyclopentyl enol ether of progesterone (Enol Luteovis) (Klopper 1965), while the last two used 10 mg of oral dydrogesterone either twice daily (El‐Zibdeh 2005) or three times daily (MacDonald 1972).

In the four studies that administered treatment IM, two studies used a dose of 500 mg of hydroxyprogesterone caproate (Le Vine 1964; Reijnders 1988), one study used 200 mg natural progesterone for three days followed by 340 mg hydroxyprogesterone caproate twice a week for 11 days (Corrado 2002), while the fourth study used a staggered dose, also of hydroxyprogesterone caproate, of between 250 to 500 mg depending on week of gestation (Shearman 1963).

The two studies that used either oral or IM routes of administration, but did not report the results for the women separately (Berle 1980; Tognoni 1980), used 15 to 20 mg/day orally of allylestrenol or 250 mg IM of hydroxyprogesterone caproate daily or every other day, and 10 mg/day orally of allylestrenol or 25 mg IM every five days of hydroxyprogesterone caproate respectively.

The remaining three studies (Gerhard 1987; Nyboe Anderson 2002; Swyer 1953) delivered treatment via 25 mg twice daily progesterone suppositories, 200 mg three times daily progesterone suppositories and six times 25 mg progesterone pellets inserted within the gluteal muscle, respectively.

Duration of treatment

There was a wide variation in treatment duration between studies. One study continued treatment until miscarriage or until 14 days after the resolution of symptoms (Gerhard 1987); two studies continued treatment for 14 or 17 days (Corrado 2002; Moller 1965); one study continued treatment for 21 days (Nyboe Anderson 2002); one study continued treatment for five weeks (Reijnders 1988); one study continued treatment for eight weeks (Tognoni 1980); one study continued treatment until the 24th week of pregnancy (Shearman 1963); and one study continued treatment until miscarriage or until 36 weeks' gestation (Le Vine 1964). One study continued treatment until the 12th week of gestation (El‐Zibdeh 2005). In the remaining five studies treatment duration was either not stated or unclear (Berle 1980; Goldzieher 1964; Klopper 1965; MacDonald 1972; Swyer 1953).

Placebo/control

Ten of the included studies compared treatment with placebo (Berle 1980; Gerhard 1987; Goldzieher 1964; Klopper 1965; Le Vine 1964; MacDonald 1972; Moller 1965; Reijnders 1988; Shearman 1963; Tognoni 1980). The remaining four studies compared progestogen administration with no treatment (Corrado 2002; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Nyboe Anderson 2002; Swyer 1953).

Baseline characteristics of participants

Gravida and parity

Two studies required women to have had three or more consecutive miscarriages (El‐Zibdeh 2005; Le Vine 1964), and five trials required women to have suffered two or more consecutive miscarriages (Goldzieher 1964; Klopper 1965; MacDonald 1972; Shearman 1963; Swyer 1953). In addition, one study (MacDonald 1972) required women to have cervical mucus ferning as evidence of "significant hormonal imbalance". Five trials accepted women with threatened imminent pregnancy loss, whether or not they had a history of previous pregnancy loss (Berle 1980; Gerhard 1987; Moller 1965; Reijnders 1988; Tognoni 1980). The remaining two studies (Corrado 2002; Nyboe Anderson 2002) enrolled women who had had amniocentesis and in vitro fertilization respectively, regardless of obstetric history.

Only one study excluded women who had experienced a live birth (Klopper 1965).

Gestation

Nine studies only accepted women within the first trimester of pregnancy (El‐Zibdeh 2005; Gerhard 1987; Klopper 1965; MacDonald 1972; Nyboe Anderson 2002; Reijnders 1988; Shearman 1963; Swyer 1953; Tognoni 1980), while three studies accepted women to the 20th gestational week (Berle 1980; Corrado 2002; Le Vine 1964). It was unclear in the remaining studies what gestational cut off, if any, was used (Goldzieher 1964; Moller 1965).

Studied outcomes

-

Miscarriage: all 14 studies included miscarriage as an outcome.

-

Preterm birth: seven studies reported preterm delivery (Corrado 2002; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Gerhard 1987; Goldzieher 1964; Le Vine 1964; Reijnders 1988; Swyer 1953).

-

Intrauterine fetal death/still birth: two studies reported intrauterine fetal death/still birth as an outcome (Corrado 2002; Swyer 1953).

-

Fetal genital abnormalities/teratogenic effects, fetal deformities: five studies (Moller 1965; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Gerhard 1987; Le Vine 1964; Reijnders 1988) reported fetal or genital abnormalities, or both, as an outcome.

-

Neonatal death: one study reported a neonatal death (Swyer 1953) and one reported perinatal death (El‐Zibdeh 2005).

-

Low birthweight less than 2500 g: birthweight was reported as an outcome in three studies (Corrado 2002; Gerhard 1987; Nyboe Anderson 2002). However, only Gerhard 1987 reported individual birthweights. Corrado 2002 and Nyboe Anderson 2002 only published a mean range.

-

Severity of morning sickness, intensified headache, nausea, or breast tenderness: no trials reported on these as separate outcomes. However, general side effects experienced by the mother were reported in two studies (Le Vine 1964; Moller 1965).

-

Thromboembolic events: no trials reported thromboembolic rates as an outcome.

-

Admission to special care unit: no trials reported admission to special care units as an outcome.

-

Maternal depression: no trials reported maternal depression as an outcome.

-

Subsequent fertility: no trials reported subsequent fertility as an outcome.

Support/sponsorship

Four studies reported support or sponsorship from pharmaceutical companies (Goldzieher 1964; MacDonald 1972; Moller 1965; Shearman 1963).

Excluded studies

On obtaining the full papers, five papers were found not to be randomized controlled trials (Check 1985; Check 1987a; Daya 1988; Rock 1985; Sidelnikova 1990), and it was unclear if there was any randomization in another (Check 1987b). Five studies had outcomes that were irrelevant to the current review (Brenner 1962; Johnson 1975; Kyrou 2011; Sondergaard 1985; Turner 1966), three used progestogen combination therapy rather than progestogen alone (Check 1995; Prietl 1992; Shu 2002), one did not administer progestogen during pregnancy (Clifford 1996), and one compared two types of progestogen rather than progestogen with no treatment or a placebo group (Smitz 1992). One additional trial was excluded due to being terminated before data collection was complete (Fuchs 1966). For the update, one trial was excluded due to using progestogen therapy after 20 weeks' gestation to prevent preterm labour (Norman 2006).

Risk of bias in included studies

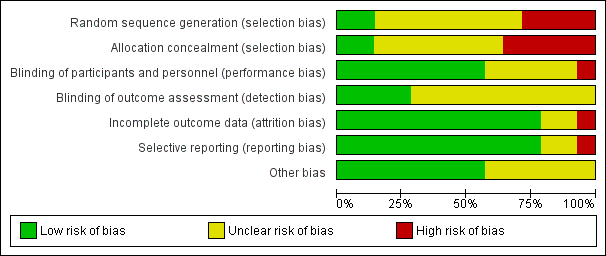

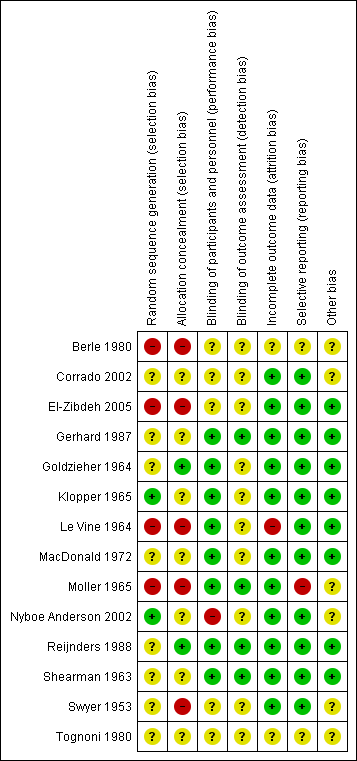

See Figure 2; Figure 3 for a summary of risk of bias in included studies.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Of the 14 studies that met the inclusion criteria, one used a random table produced by a statistician (Klopper 1965); one used a computer‐generated randomization list using clusters of 10 (Nyboe Anderson 2002); two used alternation (Berle 1980; Le Vine 1964); one allocated women by odd and even admission number (Moller 1965); one randomized by day of the week (El‐Zibdeh 2005); while the randomization of seven studies was unclear from the papers (Corrado 2002; Gerhard 1987; Goldzieher 1964; MacDonald 1972; Reijnders 1988; Shearman 1963; Tognoni 1980). In the final study (Swyer 1953), two centers took part. One center allocated by alternation, while the paper states that the other used "randomization". However, the method of randomization is not stated.

Of the 14 studies that met the inclusion criteria, three studies used ampules or bottles coded 'A' or 'B' by an unknown source (Goldzieher 1964; Le Vine 1964; Shearman 1963

One study displayed adequate allocation concealment, using sequentially numbered ampules provided by the pharmaceutical company (Reijnders 1988); in one study sequentially numbered bottles were used and the code was not broken until end (Goldzieher 1964); in five studies allocation concealment was clearly inadequate (Berle 1980; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Le Vine 1964; Moller 1965; Swyer 1953); while the allocation in the remaining studies was unclear (Corrado 2002; Gerhard 1987; Klopper 1965MacDonald 1972; Nyboe Anderson 2002; Shearman 1963; Tognoni 1980).

Blinding

Participants and providers were blinded in some studies but the majority of trials did not report on blinding of participants, providers, or outcome assessors. Eight studies used double blinding (where both the participant and treating provider do not know the allocation) (Gerhard 1987; Goldzieher 1964; Klopper 1965; Le Vine 1964; MacDonald 1972; Moller 1965; Reijnders 1988; Shearman 1963). It was unclear whether any blinding was used in the remaining included studies (Berle 1980; Corrado 2002; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Swyer 1953; Tognoni 1980). In one study, the participants knew whether they were stopping the medication or not and the providers likely knew as well (Nyboe Anderson 2002).

Incomplete outcome data

Most studies had low rates of attrition and accounted for participants well.

Of the three studies that reported withdrawals or exclusions (Corrado 2002; Gerhard 1987; Tognoni 1980), no study performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

One study reported a large number of dropouts (Le Vine 1964). Fifty‐six women were randomized but 26 women were excluded from the analysis: 16, who after randomization, were found not to be pregnant; and 10 who failed to return for injections.

Selective reporting

The majority of studies reported on all planned outcomes relevant to this review.

Other potential sources of bias

Power calculation

Three studies documented power calculations. One study (Gerhard 1987) calculated that to have a "95% confidence limit," 64 women had to be randomized. The trialists successfully enrolled 64 participants but suffered eight dropouts. The second study (Reijnders 1988) calculated that to have 80% power, 80 women needed to be enrolled. Only 64 were enrolled. The final study (Nyboe Anderson 2002) calculated that to have 80% power with a 95% confidence interval, 300 women had to be enrolled. They successfully enrolled 303.

Number of centers

One study had 12 participating centers (Tognoni 1980), one had two main participating centers with additional participating physicians (Goldzieher 1964), four had two participating centers (Klopper 1965; Nyboe Anderson 2002; Shearman 1963; Swyer 1953), five were single center (Berle 1980; Corrado 2002; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Gerhard 1987; Moller 1965), and in two studies the number of participating centers was not stated (Le Vine 1964; Reijnders 1988).

See Characteristics of included studies tables for individual details.

Effects of interventions

Fourteen trials (2158 women) met the inclusion criteria.

Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment

Primary outcomes

Miscarriage

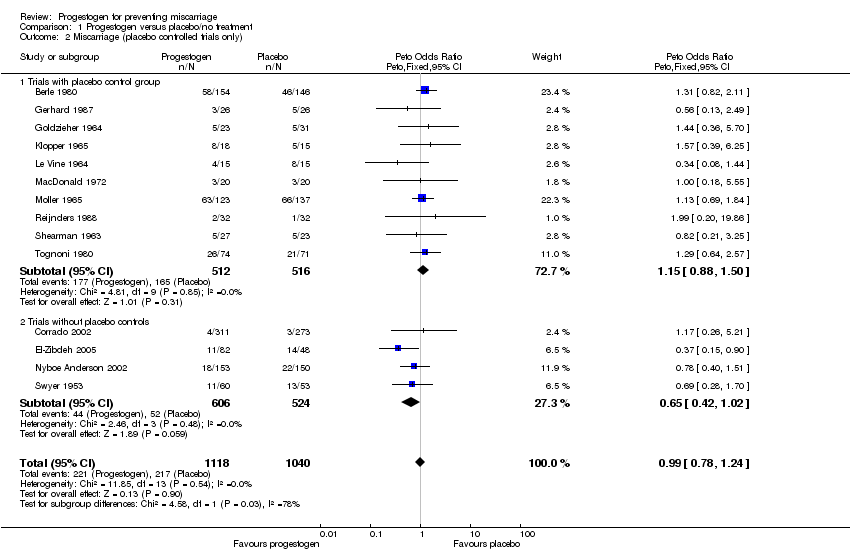

The meta‐analysis of the 14 included studies (2158 women) showed no statistically significant difference in miscarriage rates between progestogen and placebo groups (Peto odds ratio (Peto OR) 0.99; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78 to 1.24), Analysis 1.1.

A sensitivity analysis eliminating the studies at high risk of bias (Berle 1980; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Le Vine 1964; Moller 1965; Swyer 1953) did not change the results of the analysis (Peto OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.49).

A subgroup analysis was performed comparing studies that did use a placebo control and those that did not use a placebo (Corrado 2002; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Nyboe Anderson 2002; Swyer 1953). No statistically significant difference in miscarriage rates between the progestogen and placebo group was demonstrated (Peto OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.50), Analysis 1.2.

The statistical interaction test suggests that there is a difference in treatment effect between subgroups (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 4.58, df = 1 (P = 0.03), I² = 78.2%), Analysis 1.2.

Women with a history of three or more consecutive miscarriages

Two trials enrolled only women who had suffered three or more consecutive miscarriages (El‐Zibdeh 2005; Le Vine 1964). Two others provided separate pregnancy outcome data by number of previous consecutive pregnancy losses (Goldzieher 1964; Swyer 1953). The meta‐analysis showed a statistically significant reduction in miscarriage in favor of those randomized to the progestogen group (Peto OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.21 to 0.72), Analysis 1.3. However as these trials were of poorer methodological quality and might be prone to selection bias, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Because of a clinical trend toward evaluating women with 2 prior miscarriages for causes, the subgroup analysis also analyzed women with at least 2 prior miscarriages. There was a trend but not a significant reduction in miscarriage rates after progestogen treatment in this group (Peto OR 0.68; 95% CI 0.43 to 1.07).Analysis 1.3.

The statistical interaction test suggests that there is a difference in treatment effect between subgroups (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 10.73, df = 2 (P = 0.005), I² = 81.4%), Analysis 1.3.

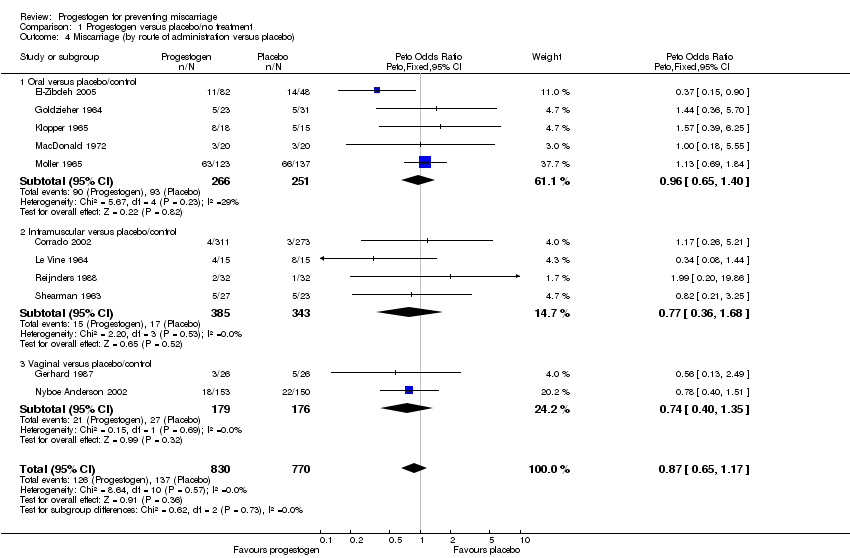

Route of administration of progestogen

Five studies compared oral progestogen with placebo/no treatment (El‐Zibdeh 2005; Goldzieher 1964; Klopper 1965; Moller 1965; MacDonald 1972). The meta‐analysis showed no statistically significant difference in miscarriages between the progestogen and placebo group (Peto OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.40), Analysis 1.4.

Four studies compared intramuscular progestogen with placebo/no treatment (Corrado 2002; Le Vine 1964; Reijnders 1988; Shearman 1963). The meta‐analysis showed no statistically significant difference in miscarriages between the progestogen and placebo group (Peto OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.36 to 1.68), Analysis 1.4

One study compared vaginally administered progestogen with placebo/no treatment (Gerhard 1987), with a second comparing it to no treatment (Nyboe Anderson 2002). The meta‐analysis showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups with respect to the incidence of recurrent miscarriage (Peto OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.40 to 1.35), Analysis 1.4.

The statistical interaction test suggests that there is no difference in treatment effect between subgroups (Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.62, df = 2 (P = 0.73), I² = 0%), Analysis 1.4.

Secondary outcomes

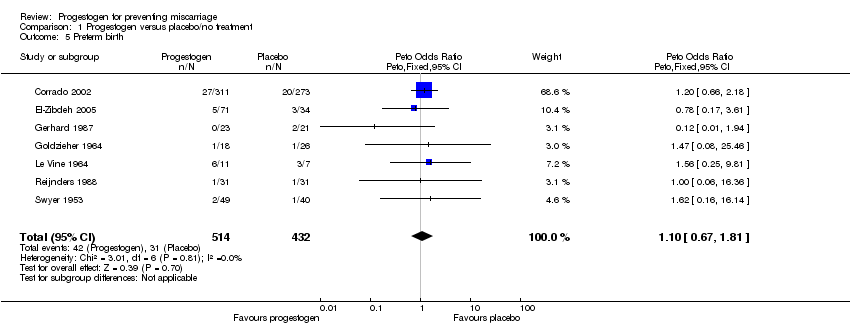

Preterm birth

Seven studies reported an incidence of premature birth (Corrado 2002; El‐Zibdeh 2005; Gerhard 1987; Goldzieher 1964; Le Vine 1964; Reijnders 1988; Swyer 1953). The meta‐analysis showed no statistically significant difference in preterm births between the progestogen and placebo group (Peto OR 1.10; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.81), Analysis 1.5. In addition, the three arms of Moller et al (Moller 1965) reported 18 preterm births but failed to give data on how these were divided between the progestogen and placebo groups.

Neonatal death

Five studies gave neonatal death as an outcome. One study reported no neonatal deaths in either group (Gerhard 1987); one study reported no difference in perinatal death (2.8% in progesterone group, 2.9% in controls) (El‐Zibdeh 2005); the meta‐analysis of the five studies (El‐Zibdeh 2005; Gerhard 1987; Reijnders 1988; Swyer 1953; Tognoni 1980 showed no significant difference between treatment and placebo (Peto OR 1.38; 95% CI 0.72 to 2.64), Analysis 1.6. In addition, Moller 1965 reported eight neonatal deaths but again failed to give data on how these were divided between the progestogen and placebo groups.

Birthweight

One study (Gerhard 1987) studied birthweight. It reported no incidence of a baby born weighing less than 2500 g. Two other studies also reported birthweight but provided a mean range rather than individual data (Corrado 2002; Nyboe Anderson 2002). There were no statistically significant differences in the mean weight of babies in either study.

Fetal abnormalities

Four studies reported fetal abnormalities as an outcome (El‐Zibdeh 2005; Gerhard 1987; Le Vine 1964; Reijnders 1988). Two studies reported no incidence of fetal abnormalities (Gerhard 1987; Le Vine 1964). One study reported a single case of fetal genital abnormality in the progestogen group (Reijnders 1988). There was no statistically significant difference in fetal genital anomalies (Peto OR 7.64; 95% CI 0.15 to 385.21), Analysis 1.7. One study reported two anomalies in the progestogen group (neural tube defect and non‐immune hydrops) and one case of multiple anomalies in the control group in a baby with Down's syndrome (El‐Zibdeh 2005). No genital anomalies were noted in that study. In addition, the Moller et al study (Moller 1965) reported one case of fetal abnormality in the progestogen group but, due to inconsistency in the method used for reporting numbers, could not be included in the meta‐analysis. (That is, in total there were 131 successful pregnancies and 139 live births. The numbers for successful pregnancies are divided into progestogen and placebo groups. However, the live births are not separated in this manner. The one baby with fetal abnormalities is given in the figures for live births rather than successful pregnancies).

Maternal adverse events

Two studies listed maternal adverse effects as outcomes (Le Vine 1964; Moller 1965). No events were noted.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The aim of this review was to assess the effectiveness of progestogens to prevent miscarriage. Although there has been much speculation that progestogens may reduce the miscarriage rate, the results of this meta‐analysis show no statistically significant difference between women receiving progestogen and those receiving only placebo or no treatment, when no provision is made for obstetric history. Subgroup analysis by method of administration (oral, intramuscular or vaginal) also showed no statistically significant difference between progestogen and placebo groups.

However, when provision was made for obstetric history, by way of a subgroup analysis only including women who had suffered three or more consecutive miscarriages directly prior to the studied pregnancy, a statistically significant difference was found in favor of the progestogen group. This finding should be approached with caution, however, as numbers are small and the trials were of poor methodological quality. Two trials are currently underway to further evaluate therapy in this subgroup of women. In addition, some studies included data for women who had two or more miscarriages but as this is not the classic definition of recurrent miscarriage, a separate analysis including these women was not carried out.

The meta‐analysis showed no statistically significant difference in the number of fetal abnormalities (including virilization and hypospadias) in babies whose mothers had been given progestogens whilst in vitro, nor in intrauterine death/still birth or neonatal death.

There has been much discussion as to whether progestogen may prevent preterm birth (Keirse 1990). There was no statistically significant difference in our meta‐analysis between the number of preterm births in the progestogen and placebo groups. However, it is important to note that this systematic review only assesses progestogen given in early pregnancy to prevent miscarriage, rather than trials assessing progestogen given in the second or third trimester to try to prevent preterm delivery.

No studies reported adverse maternal effects.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The data appear mostly consistent, particularly regarding women with recurrent losses. The ongoing trials in this population will provide data for future updates.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence was moderately good. The majority of the studies were conducted before robust reporting of methods was instituted. This led to "unclear" evaluations for many of the study 'Risk of bias' categories based simply on the area not being explicitly stated. For the time the studies were performed, the overall quality appears to be reasonable.

Potential biases in the review process

The review process identified trials from a heterogenous set of conditions. All used the same treatment for the same outcome, however the differences in condition make the data difficult to interpret.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

These results for women with recurrent miscarriage agree with a systematic review conducted by Coomarasamy 2011 that included four of the trials included in this review.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, outcome: 1.1 Miscarriage (all trials).

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 1 Miscarriage (all trials).

Comparison 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 2 Miscarriage (placebo controlled trials only).

Comparison 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 3 Miscarriage (women with previous recurrent miscarriage only).

Comparison 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 4 Miscarriage (by route of administration versus placebo).

Comparison 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 5 Preterm birth.

Comparison 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 6 Neonatal death.

Comparison 1 Progestogen versus placebo/no treatment, Outcome 7 Fetal genital abnormalities/virilisation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Miscarriage (all trials) Show forest plot | 14 | 2158 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.78, 1.24] |

| 2 Miscarriage (placebo controlled trials only) Show forest plot | 14 | 2158 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.78, 1.24] |

| 2.1 Trials with placebo control group | 10 | 1028 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.88, 1.50] |

| 2.2 Trials without placebo controls | 4 | 1130 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.42, 1.02] |

| 3 Miscarriage (women with previous recurrent miscarriage only) Show forest plot | 10 | 1287 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.66, 1.07] |

| 3.1 Women with a history of 3 or more prior miscarriages | 4 | 225 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.21, 0.72] |

| 3.2 Women with a history of 2 or more prior miscarriage | 7 | 450 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.43, 1.07] |

| 3.3 Women with unspecified prior miscarriages presenting with threatened miscarriage | 3 | 612 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.84, 1.63] |

| 4 Miscarriage (by route of administration versus placebo) Show forest plot | 11 | 1600 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.65, 1.17] |

| 4.1 Oral versus placebo/control | 5 | 517 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.65, 1.40] |

| 4.2 Intramuscular versus placebo/control | 4 | 728 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.36, 1.68] |

| 4.3 Vaginal versus placebo/control | 2 | 355 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.40, 1.35] |

| 5 Preterm birth Show forest plot | 7 | 946 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.67, 1.81] |

| 6 Neonatal death Show forest plot | 5 | 445 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.72, 2.64] |

| 7 Fetal genital abnormalities/virilisation Show forest plot | 4 | 228 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.64 [0.15, 385.21] |