Tratamiento antiinflamatorio para la carditis en la fiebre reumática aguda

Referencias

Referencias de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios excluidos de esta revisión

Referencias adicionales

Referencias de otras versiones publicadas de esta revisión

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Methods | DESIGN ALLOCATION BLINDING WITHDRAWALS | |

| Participants | INCLUSION CRITERIA RANDOMISED (N = 57) 2 PARTICIPANT GROUPS AT START OF TREATMENT

GRADE 3 APICAL SYSTOLIC MURMURS AT START WITHDRAWALS AGE (average in years) SEX (M:F) | |

| Interventions | TEST GROUP ‐ Followed by 3 wk of observation ‐ Total dose = 3 g CONTROL ‐ Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)

CO‐TREATMENT | |

| Outcomes | ANALYSIS PARTICIPANTS WITH CARDIAC MURMURS 1 YEAR ‐ Prednisone = 16/28

‐ ASA = 9/27

GRADE 3 MURMURS AT I YEAR | |

| Notes | ‐ Full‐text paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Each of the 8 hospitals was given a series of sealed envelopes prepared by the Department of Medical Statistics, New York University, which determined whether the patient should receive prednisone or acetylsalicylic acid" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 4 participants who switched from aspirin to prednisone were analysed separately, not as aspirin |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not clearly outlined in Methods, so difficult to assess |

| Methods | DESIGN ALLOCATION BLINDING WITHDRAWALS | |

| Participants | INCLUSION CRITERIA RANDOMISED (N = 160) ‐ Prednisone = 18 DOUBLE‐BLIND (DB) GROUP ‐ Prednisone = 16 ‐ ASA = 18 GRADE 3 APICAL SYSTOLIC MURMURS AT START WITHDRAWALS AGE (average in years) SEX (M:F) | |

| Interventions | TEST GROUP ‐ Prednisone 3 mg/lb for 7 d. Second course if persistent carditis after 1 wk (both carditis and polyarthritis groups) CONTROL GROUP ‐ ASA

CO‐TREATMENT | |

| Outcomes | ANALYSIS PATIENTS WITH CARDIAC DISEASE AT 1 YEAR POLYARTHRITIS GROUP (3 dropouts) GRADE 3 APICAL SYSTOLIC MURMURS AT 1 YEAR (SB & DB groups) OTHER OUTCOMES AFTER 3 WK | |

| Notes | ‐ Full‐text paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Two separate sets of sealed envelopes (prepared by the Department of Medical Statistics, New York University), one for carditis and one for the polyarthritis cases, were given to each of the 7 participating hospitals" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | During first 2 years of study, medication given on single‐blind basis and chief investigator moved participants to different groups |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | During first 2 years of study, medication given on single‐blind basis and chief investigator moved participants to different groups |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 3 participants who were switched from ASA to prednisone were analysed separately, not as ASA |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not clearly outlined in Methods, so difficult to assess |

| Methods | DESIGN ALLOCATION BLINDING | |

| Participants | INCLUSION CRITERIA RANDOMLY ASSIGNED (N = 131) WITHDRAWALS AGE (average in years) SEX (M:F) | |

| Interventions | TEST GROUP ‐ Hydrocortisone orally

CONTROL GROUP CO‐TREATMENT | |

| Outcomes | ANALYSIS PATIENTS WITH CARDITIS AT 1 YEAR APICAL SYSTOLIC GRADE 3 MURMURS AT 1 YEAR DEVELOPMENT OF MURMURS IN PARTICIPANTS WITH NO PREVIOUS MURMURS AFTER 1 YEAR OTHER OUTCOMES EFFECT OF TREATMENT ON THE FOLLOWING PARAMETERS ‐ No numbers given. Generalisations and graphs provided

Salicylates have a lesser effect on ESR | |

| Notes | ‐ Full‐text paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The therapeutic group for each patient was determined by a sealed envelope technique. The envelopes were so arranged that all forms of therapy were used during the entire period of the study in order to obviate temporal effects" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: "It was impossible for the observers to be ignorant of therapeutic groups because of the striking effects of hormone therapy" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: "It was impossible for the observers to be ignorant of therapeutic groups because of the striking effects of hormone therapy" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 16% of participants withdrew from the studies, died or were lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not clearly stated in Methods section, so difficult to assess |

| Methods | DESIGN ALLOCATION BLINDING WITHDRAWALS | |

| Participants | INCLUSION CRITERIA RANDOMLY ASSIGNED (N = 35) ‐ Placebo = 16 GRADING OF SEVERITY OF CARDITIS AT START WITHDRAWALS AGE (average in years) SEX (M:F) | |

| Interventions | TEST GROUP PLACEBO CO‐TREATMENT | |

| Outcomes | ANALYSIS PARTICIPANTS WITH MURMURS, SURGERY OR DEATH AT LONG‐TERM FOLLOW‐UP OF 15 MONTHS TO 6 YEARS (mean = 3 years and 11 months) OUTCOME OF PARTICIPANTS WITH SEVERE CARDITIS OTHER SHORT‐TERM OUTCOMES ‐ No detailed analysis provided

(recorded as similar in both groups) | |

| Notes | ‐ Full‐text paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | States only that codes were assigned in a randomised fashion, with no description |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The tablets were given according to a numerical code which was known only to the chief hospital pharmacist, each patient being assigned a coded number in a randomised fashion the same number appearing on the tablet‐container for a particular patient. The code was sealed and kept in a safe for the entire duration of the trial" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Neither the clinicians nor the patients were aware of what tablets were being administered, i.e. the trial was double‐blind" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Even at follow‐up visits the investigator was unaware of the identity of the medication given to any particular patient. The code was not broken until 7 years after the initiation of the trial, after all the relevant patient data, including long term follow‐up, had been collected" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 35 participants in total, 19 in prednisone, 16 in placebo; 2 in each group lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcomes not clearly stated in Methods section, so difficult to assess |

| Methods | DESIGN ALLOCATION BLINDING WITHDRAWALS | |

| Participants | INCLUSION CRITERIA RANDOMLY ASSIGNED (N = 99) NO GRADING SYSTEM OF SEVERITY FOR RANDOMLY ASSIGNED PARTICIPANTS WITHDRAWALS AGE (average in years) SEX (M:F) | |

| Interventions | TEST GROUP (corticosteroids in large doses) CONTROL GROUP CO‐TREATMENT | |

| Outcomes | ANALYSIS PARTICIPANTS WITH "SIGNS OF RHEUMATIC HEART DISEASE" AT 1 YEAR OTHER OUTCOMES | |

| Notes | ‐ Full‐text paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Some participants in the groups "no therapy", "post‐co‐op hormone" and "small‐dose hormone" were consecutively allocated, but these participants were not included in the analysis Aspirin and hormone groups (included in analysis) were randomly assigned in some fashion Quote: "been selected at random for treatment with aspirin or hormones", but no description was provided of what random selection was. However, because more participants were given hormones than aspirin, investigators included some participants who were given aspirin as part of another trial |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Some participants given aspirin in another trial were included in the analysis |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Arms appear relatively similar |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | List of outcomes assessed in the study not clearly outlined |

| Methods | DESIGN ALLOCATION BLINDING WITHDRAWALS | |

| Participants | INCLUSION CRITERIA RANDOMLY ASSIGNED (N = 497) GRADE 3 SYSTOLIC MURMURS AT START (grading of murmurs from 0 to 3) EARLY WITHDRAWALS TREATMENT STOPPED OR TREATMENT CHANGED DURING STUDY AGE (mean age in years) SEX (M:F) | |

| Interventions | TEST GROUP (corticosteroids) CONTROL GROUP CO‐TREATMENT | |

| Outcomes | ANALYSIS MURMURS PRESENT AT 1 YEAR (includes groups A, B, C) GRADE 3 SYSTOLIC MURMURS AT 1 YEAR GROUP A: murmurs at the end of 1 year, no grading given DEATHS AT 1 YEAR PERICARDITIS AND/OR CONGESTIVE FAILURE AT 13 WEEKS (END OF THERAPY) OTHER OUTCOMES | |

| Notes | ‐ Full‐text paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Using random sampling numbers and keeping the numbers of patients on the three treatments approximately equal in each centre" Comment: random sampling numbers not stated, not stated whether stratification occurred |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The coordinating centre in each country issued serially numbered and sealed envelopes to the treatment centres. Thus, on admission of a patient of given age and specified duration‐from‐onset group, the investigator at the treatment centre had merely to open the next available envelope for that particular group to find a statement of the treatment to be applied" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "The allocation was both "blind" and random"; not described better than that |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No differences between arms apparent; all outcomes apparently reported; participants switching treatments apparently analysed in groups to which they were assigned |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes not clearly reported in Methods section |

| Methods | DESIGN ALLOCATION BLINDING WITHDRAWALS | |

| Participants | INCLUSION CRITERIA ‐ Rheumatic activity (128/135 = first attack of rheumatic fever) ‐ Diagnosis of rheumatic activity according to Jones criteria not indicated ‐ Final evaluations made at 14 months (by 1 of 3 observers) for cardiac murmurs = apical systolic, apical mid‐diastolic murmurs and aortic diastolic murmurs ‐ Average days of illness at time of treatment

RANDOMLY ASSIGNED (N = 152) NO GRADING OF MURMURS PERFORMED. WITHDRAWALS AGE SEX | |

| Interventions | TEST GROUP (ASA) CONTROL GROUP (corticosteroids) CO‐TREATMENT | |

| Outcomes | ANALYSIS SIGNIFICANT OUTCOME OF PARTICIPANTS WITH PREEXISTING HEART DISEASE DEVELOPING NEW MURMURS WITH TREATMENT OTHER OUTCOMES | |

| Notes | ‐ Full‐text paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Each patient was assigned a number in consecutive fashion, and the selection of the form of therapy was predetermined in a random fashion" Comment: The random fashion was not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "An independent observer, who knew nothing of the patient's history, previous or present cardiac findings, or therapy, examined 87% of the patients between the 10th and 16th month after the start of therapy. Complete agreement on the presence or absence of a murmur and its significance was obtained in 76% of the patients" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All outcomes apparently reported with all participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes apparently reported |

| Methods | DESIGN ALLOCATION BLINDING WITHDRAWALS | |

| Participants | INCLUSION CRITERIA RANDOMLY ASSIGNED (N = 61) CARDITIS (N = 39) SEVERITY OF CARDITIS BASED ON ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS AT START WITHDRAWALS AGE (average in years) SEX (M:F) | |

| Interventions | TEST GROUP CONTROL GROUP CO‐TREATMENT | |

| Outcomes | ANALYSIS PRESENCE OF CARDITIS AT 1 YEAR PARTICIPANTS WITH CARDITIS AT 1 YEAR CARDIAC OUTCOMES ACCORDING TO SEVERITY AT 1 YEAR OTHER OUTCOMES | |

| Notes | ‐ Full‐text paper | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was by small‐group, random‐number allocation" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...cardiologists were unaware of the nature of the infusion being administered" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Not all numbers reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | 2 minor outcomes (tricuspid and pulmonary regurgitation) listed in the Methods do not appear to have been reported in the Results |

AI = aortic incompetence; ASA = aspirin or acetylsalicylic acid; DB = double‐blinded; MI = myocardial infarction; SB = sIngle‐blinded.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Not a randomised trial. 18 participants with a diagnosis of acute rheumatic carditis and no steroids or salicylates given in the preceding 2 wk were given intravenous high‐dose methylprednisolone | |

| Review study | |

| Review of participants who participated in the Cooperative Clinical Trial of ACTH, Cortisone and Aspirin in 1955. See RFWP 1955 in included studies | |

| Randomised clinical trial, but does not meet inclusion criterion of follow‐up of at least 3 months. Participants followed up for only 4 weeks | |

| Not a randomised trial. Duration of illness was compared in 13 participants receiving oral corticosteroids and 13 receiving pulse therapy | |

| Not a randomised trial. Retrospective analysis | |

| Not a randomised trial. Mode of treatment assignment not clear | |

| Not a randomised trial. Prednisone was administered to all selected participants | |

| Not a randomised trial. Follow‐up study of participants receiving cortisone, ACTH and no specific therapy sequentially 6 to 9 years earlier | |

| Randomised trial assessing use of naproxen as an alternative to aspirin in the treatment of arthritis of rheumatic fever. Inclusion criteria not met | |

| Not a randomised trial. 36 participants with rheumatic carditis given high doses of intravenous methylprednisolone | |

| Not a randomised trial. 70 children with active rheumatic fever treated with intravenous boluses of methylprednisolone 3 times a week | |

| Not a randomised trial. Retrospective analysis of outcomes of 242 participants with severe rheumatic carditis after discharge and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone or oral prednisone | |

| Not a randomised trial. 3 study groups of moderate cardiac disease, severe heart disease and life‐threatening heart disease alternatively assigned to treatment with prednisone or salicylates. Outcomes assessed were clinical response, ESR response and hospital stay in days | |

| Letter | |

| Not a randomised trial. Varying doses of cortisone administered orally to participants with active rheumatic fever | |

| Not a randomised trial. Reported outcomes were acute phase reactants. No cardiac outcomes outlined | |

| Review article | |

| Not a randomised trial. Cardiac outcomes assessed after 3 months. Outcome data not given as numbers of patients responding to treatment, but rather as a mean | |

| Not a randomised trial. 111 participants with rheumatic carditis treated with steroids | |

| Participants did not have carditis | |

| Randomised controlled trial, but does not meet inclusion criterion of follow‐up of at least 3 months | |

| Letter | |

| Not a randomised trial. Retrospective review of participants with diagnosis of rheumatic fever treated with naproxen | |

| Not a randomised trial. Corticotropin administered to 28 participants with 32 attacks of active carditis. Control observations made on 7 participants who did not receive corticotropin | |

| Not a randomised trial. Participants with active rheumatic carditis treated with short‐term steroids for 7 days |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Cardiac disease after 1 year Show forest plot | 6 | 907 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.66, 1.15] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus aspirin, Outcome 1 Cardiac disease after 1 year. | ||||

| 2 Outcome of severe cardiac disease after 1 year Show forest plot | 3 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.32, 2.70] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus aspirin, Outcome 2 Outcome of severe cardiac disease after 1 year. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

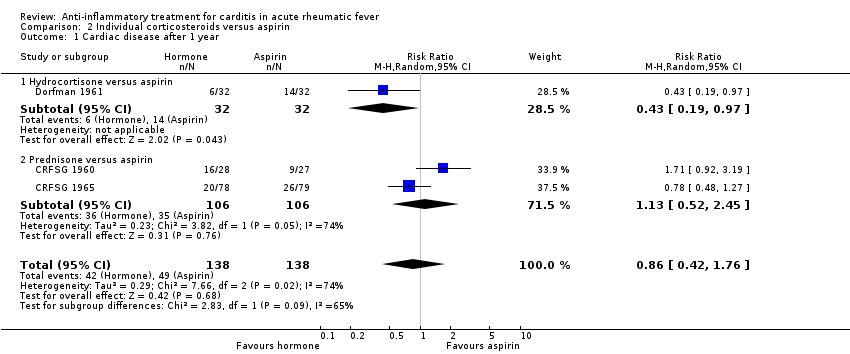

| 1 Cardiac disease after 1 year Show forest plot | 3 | 276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.42, 1.76] |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Individual corticosteroids versus aspirin, Outcome 1 Cardiac disease after 1 year. | ||||

| 1.1 Hydrocortisone versus aspirin | 1 | 64 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.19, 0.97] |

| 1.2 Prednisone versus aspirin | 2 | 212 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.52, 2.45] |

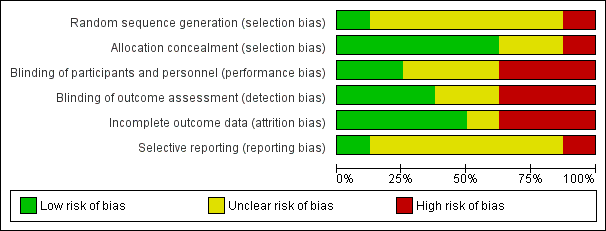

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

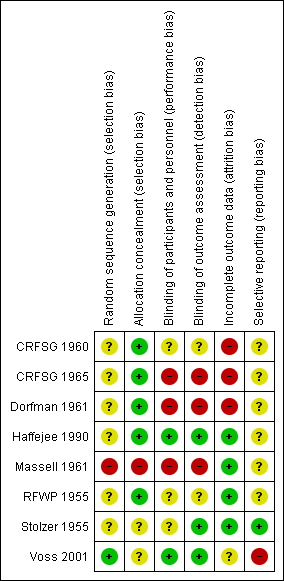

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus aspirin, Outcome 1 Cardiac disease after 1 year.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus aspirin, Outcome 2 Outcome of severe cardiac disease after 1 year.

Comparison 2 Individual corticosteroids versus aspirin, Outcome 1 Cardiac disease after 1 year.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Cardiac disease after 1 year Show forest plot | 6 | 907 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.66, 1.15] |

| 2 Outcome of severe cardiac disease after 1 year Show forest plot | 3 | 119 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.32, 2.70] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Cardiac disease after 1 year Show forest plot | 3 | 276 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.42, 1.76] |

| 1.1 Hydrocortisone versus aspirin | 1 | 64 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.19, 0.97] |

| 1.2 Prednisone versus aspirin | 2 | 212 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.52, 2.45] |