Antibióticos para las exacerbaciones del asma

Resumen

Antecedentes

El asma es una afección respiratoria crónica que afecta a más de 300 000 000 de adultos y niños en todo el mundo. Se caracteriza por sibilancia, tos, opresión torácica y disnea. Habitualmente los síntomas son intermitentes, pueden empeorar en un tiempo corto y dar lugar a una exacerbación. Las exacerbaciones del asma pueden ser graves y dar lugar a la hospitalización o incluso a la muerte en algunos pocos casos. Las exacerbaciones se pueden tratar en general con la intensificación de la medicación habitual del paciente, como los esteroides orales. Aunque en ocasiones los antibióticos se incluyen en el régimen de tratamiento, se considera que las infecciones bacterianas son responsables de solo una minoría de las exacerbaciones y las guías actuales señalan que los antibióticos se deben reservar para los casos en los que haya signos, síntomas o resultados de las pruebas de laboratorio claros que indiquen una infección bacteriana.

Objetivos

Determinar la eficacia y la seguridad de los antibióticos en el tratamiento de las exacerbaciones del asma.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se realizaron búsquedas en el registro de ensayos del Grupo Cochrane de Vías Respiratorias (Cochrane Airways Trials Register), que contiene registros compilados a partir de múltiples recursos electrónicos y de búsqueda manual. También se buscó en los registros de ensayos y en listas de referencias de estudios primarios. La búsqueda más reciente se hizo en octubre de 2017.

Criterios de selección

Se incluyeron los estudios que compararon la antibioticoterapia para las exacerbaciones del asma en adultos o niños versus placebo o atención habitual que no incluyó antibióticos. Se permitió que los estudios incluyeran cualquier tipo de antibiótico, cualquier dosis y cualquier duración, siempre que el objetivo fuera tratar la exacerbación. Se incluyeron los estudios paralelos de cualquier duración realizados en cualquier contexto y se planificó incluir los ensayos grupales. Se excluyeron los ensayos cruzados (crossover). Se incluyeron los estudios que se informaron como artículos de texto completo, los publicados solo como resúmenes y los datos no publicados.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Al menos dos autores de la revisión examinaron los resultados de búsqueda para los estudios elegibles. Se extrajeron los datos de los resultados, el riesgo de sesgo se evaluó por duplicado y las discrepancias se solucionaron con la inclusión de otro autor de la revisión. Los datos dicotómicos se analizaron como odds ratios (OR) o diferencias de riesgos (DR), y los datos continuos se analizaron como diferencias de medias (DM), todos con un modelo de efectos fijos. Los datos asimétricos se describieron en forma narrativa. Se calificaron los resultados y se presentó la evidencia en las tablas "Resumen de los hallazgos" para cada comparación. Los resultados primarios fueron ingreso a la unidad de cuidados intensivos/unidad de alta dependencia (UCI/UAD), duración de los síntomas/las exacerbaciones y todos los eventos adversos. Los resultados secundarios fueron mortalidad, duración del ingreso hospitalario, recaída después de la presentación índice y tasa de flujo espiratorio máximo (TFEM).

Resultados principales

Seis estudios cumplieron los criterios de inclusión e incluyeron 681 adultos y niños con exacerbaciones del asma. La edad promedio en los tres estudios en adultos varió de 36,2 a 41,2 años. Los tres estudios en niños aplicaron diferentes criterios de inclusión, con una variación de uno a 18 años de edad. Cinco estudios excluyeron explícitamente a participantes con signos y síntomas obvios de infección bacteriana (es decir, los que con claridad se ajustaban a las guías actuales para recibir antibióticos). Cuatro estudios investigaron antibióticos macrólidos y dos estudios investigaron penicilinas (amoxicilina y ampicilina); los dos estudios que utilizaron penicilinas se realizaron hace más de 35 años. Cinco estudios compararon antibióticos versus placebo, y uno fue abierto. El seguimiento de los estudios varió de una a doce semanas. Los ensayos fueron de calidad metodológica variada, y solo fue posible realizar un metanálisis limitado.

Ninguno de los ensayos incluidos informó el ingreso a la UCI/UAD, aunque un participante en el grupo placebo de un estudio que incluyó niños con estado asmático presentó un paro respiratorio y fue ventilado. Cuatro estudios informaron síntomas de asma, pero solo fue posible combinar los resultados para dos estudios sobre macrólidos con 416 participantes; la DM en la puntuación de síntomas del cuaderno diario fue ‐0,34 (intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: ‐0,60 a ‐0,08); las puntuaciones inferiores (en una escala de 7 puntos) denotan mejores síntomas. Dos estudios con macrólidos informaron los días sin síntomas. Un estudio de 255 adultos informó el porcentaje de días sin síntomas a los diez días como 16% en el grupo de antibiótico y 8% en el grupo placebo. En un estudio adicional de 40 niños, los autores del estudio informaron significativamente más días sin síntomas en todos los puntos temporales en el grupo de antibiótico comparado con el grupo de atención habitual. El mismo estudio informó la duración en días de la exacerbación del asma índice, nuevamente a favor del grupo de antibiótico. Un estudio de una penicilina que incluyó 69 participantes informó los síntomas del asma al alta hospitalaria; se informó que la diferencia entre los grupos para ambos estudios no fue significativa.

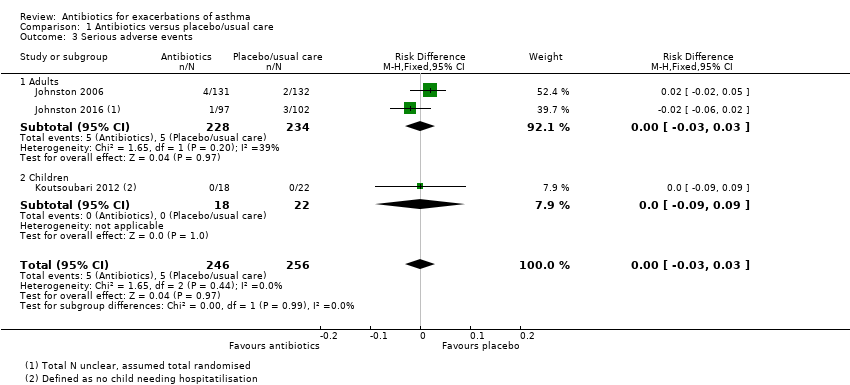

Se combinaron los datos para los eventos adversos graves de tres estudios que incluyeron a 502 participantes, pero los eventos fueron poco frecuentes; los tres ensayos solo informaron diez eventos: cinco en el grupo de antibiótico y cinco en el grupo placebo. Se combinaron los datos para todos los eventos adversos (EA) de tres estudios, pero la estimación del efecto fue imprecisa (OR 0,99; IC del 95%: 0,69 a 1,43). No se informaron muertes en ninguno de los estudios incluidos.

Dos estudios que investigaron penicilinas informaron la duración del ingreso; ningún estudio informó diferencias entre los grupos. En un estudio (263 participantes) de macrólidos, se informó que dos participantes en cada brazo presentaron una recaída, definida como una exacerbación adicional, en los puntos temporales a las seis semanas. Se combinaron los resultados de la variable principal de evaluación TFEM a los diez días para dos estudios de macrólidos; el resultado favoreció a los antibióticos sobre placebo (DM 23,42 l/min, IC del 95%: 5,23 a 41,60). Un estudio en niños informó que el flujo máximo registrado durante el período de seguimiento favoreció a la claritromicina, pero el intervalo de confianza no incluyó ninguna diferencia (DM 38,80; IC del 95%: ‐11,19 a 88,79).

La calificación de los resultados varió de calidad moderada a muy baja, que se disminuyó debido a la sospecha de sesgo de publicación, indireccionalidad, imprecisión y a la deficiente calidad metodológica de los estudios.

Conclusiones de los autores

Se encontró evidencia limitada de que los antibióticos administrados en el momento de una exacerbación del asma pueden mejorar los síntomas y la TFEM al seguimiento, comparados con atención habitual o con placebo. Sin embargo, los resultados fueron inconsistentes entre los seis estudios heterogéneos incluidos; dos se realizaron hace más de 30 años y la mayoría de los participantes incluidos en esta revisión se reclutaron de servicios de urgencias, lo que limita la aplicabilidad de los resultados a esta población. Por lo tanto, la certeza con respecto a estos resultados es limitada. No se encontró evidencia suficiente para establecer conclusiones acerca de numerosos resultados importantes para los pacientes (p.ej. ingreso hospitalario). No fue posible descartar una diferencia entre los grupos en cuanto a todos los eventos adversos, pero los eventos adversos graves fueron poco frecuentes.

PICOs

Resumen en términos sencillos

¿Los antibióticos son un tratamiento adicional seguro y efectivo para las exacerbaciones del asma?

Información general sobre el tema

El asma es una afección respiratoria crónica común que afecta a adultos y niños en todo el mundo. Los pacientes pueden experimentar empeoramientos a corto plazo de los síntomas, a menudo conocidos como exacerbaciones (o crisis asmáticas). Las exacerbaciones se tratan en general con la intensificación de la medicación del paciente (p.ej. administrar comprimidos de corticosteroides durante algunos días). En ocasiones las exacerbaciones se pueden desencadenar por infecciones como los virus. Ocasionalmente, una infección bacteriana en los pulmones o las vías respiratorias podría causar una exacerbación. Los síntomas de una infección bacteriana incluyen estertores crepitantes en el tórax, fiebre y expectoración de grandes volúmenes de esputo decolorado. Las infecciones bacterianas se pueden confirmar mediante pruebas de laboratorio, por ejemplo, análisis de sangre; sin embargo, dichas pruebas no siempre están disponibles en la atención primaria (en el MG). Las infecciones bacterianas pueden requerir tratamiento con antibióticos.

En esta revisión se deseaba determinar si los antibióticos son útiles y seguros para los pacientes que tienen exacerbaciones del asma. Parte de la motivación para esta revisión es la inquietud de que los antibióticos se pueden prescribir en exceso para los pacientes con exacerbaciones del asma.

Características de los estudios

Se buscaron los estudios que compararon un grupo de pacientes a los que se les administró cualquier tipo o dosis de antibiótico con un grupo de pacientes a los que no se les administró un antibiótico para una exacerbación. Solo se incluyeron los estudios en los que se decidió por azar quién recibiría el antibiótico. Se incluyeron estudios en adultos y niños, realizados en cualquier momento y en cualquier lugar del mundo.

Resultados clave

Se encontraron seis estudios que incluyeron 681 adultos y niños con asma. Dos de estos estudios se realizaron hace más de 35 años.

En general, se encontró escasa evidencia que indicó que los antibióticos pueden mejorar los síntomas y los resultados de las pruebas respiratorias comparados con ningún antibiótico. No existe mucha certeza acerca de estos resultados porque solo se incluyó en la revisión un número pequeño de estudios y pacientes. Uno de los resultados primarios (ingreso en la unidad de cuidados intensivos/unidad de alta dependencia [UCI/UAD]) no se informó.

Tampoco fue posible tener seguridad acerca de si los pacientes que recibieron antibióticos tienen más o menos eventos adversos (efectos secundarios). Solo diez pacientes (cinco que recibieron antibióticos y cinco que recibieron placebo/ningún antibiótico) de 502 tuvieron un evento adverso grave.

Se encontró poca evidencia acerca de otros resultados importantes, como el ingreso hospitalario u otra exacerbación durante el período de seguimiento de los estudios.

El estudio más reciente encontró difícil reclutar a los pacientes con asma porque muchos de ellos ya habían recibido un antibiótico, por lo que no pudieron participar.

Calidad de la evidencia

En general, existe baja certeza acerca de la evidencia presentada en esta revisión. Se considera que es posible que algunos estudios de antibióticos para las exacerbaciones del asma se hayan realizado pero no publicado, ya que fue posible encontrar muy pocos estudios acerca de esta importante pregunta. También existe la inquietud acerca de cuán bien se aplican los hallazgos de los estudios a todos los pacientes con crisis asmáticas, porque la mayoría de los estudios que se encontraron solo reclutaron pacientes en hospitales y servicios de urgencias. Además, dos de los estudios eran antiguos, y el tratamiento del asma ha cambiado mucho en 30 años. Debido a que solo se encontraron unos pocos estudios, en algunos casos no fue posible determinar si los antibióticos son mejores, peores o similares a ningún antibiótico. Finalmente, existen algunas inquietudes por la manera en la que se realizaron los estudios, por ejemplo, en un estudio los pacientes y el personal del estudio sabían quién recibía el antibiótico y quién no; lo anterior podría haber afectado la manera como se comportaron los pacientes o el personal.

Conclusiones

Se encontró evidencia muy limitada de que los antibióticos pueden ayudar a los pacientes que tienen crisis asmáticas, para lo cual aún existe muy poca certeza. En particular, no se encontró mucha información acerca de resultados importantes como los ingresos hospitalarios o los efectos secundarios. Sin embargo, los efectos secundarios graves fueron muy poco frecuentes en los estudios encontrados.

Conclusiones de los autores

Summary of findings

| Antibiotics compared to placebo/usual care for acute asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute asthma exacerbation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo/usual care | Risk with antibiotics | |||||

| ICU/HDU admission ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | One respiratory arrest in the placebo group in Shapiro 1974. No other studies reported this outcome |

| Symptom score at 10 days. Measured on a 7‐point scale (0 to 6) ; lower score denotes fewer symptoms | Mean symptom score at 10 days ranged from 2 to 2.20 points | MD 0.34 points lower (0.60 lower to 0.08 lower) | ‐ | (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a,d MODERATE | |

| All adverse events | 42 per 100 | 41 per 100 | OR 0.99 | 506 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | 2 studies in adults and 1 small old study in children with status asthmaticus |

| Serious adverse events Duration 3 days to 3 weeks | 2 per 100 | 2 per 100 | RD 0.00 | 502 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Anticipated absolute effects were calculated using the figures in Figure 1. This is a re‐presentation of the results, but to 4 dp, which allows the calculation to be done |

| Mortality ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No deaths were reported in any of the studies |

| Length of hospital stay, days | Mean length of hospital stay was 2.6 days | MD 0.1 days lower | ‐ | 43 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | 1 study reported medians and IQRs and found no significant differences, although data were skewed |

| Relapse after index presentation ‐ not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| PEFR (GIV) Duration 10 days | Mean PEFR (GIV) ranged from 19.6 to 26.9 L/min (mean difference from baseline) | MD 23.42 L/min (mean difference from baseline) higher | ‐ | 469 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. | ||||||

| a‐1 indirectness. Studies mostly recruited from hospital or emergency department. Therefore this review may represent more severe exacerbations and does not apply to people attending the GP and requesting antibiotics. The review does not apply to people who have already received a course of antibiotics. bNo downgrade for risk of bias. One small study excluded 6 participants post hoc, but excluding this study from the meta‐analysis did not affect the results. cNo downgrade. I2 = 0. Different antibiotics were given in each study. dNo downgrade. Only six RCTs have been published on antibiotics for asthma exacerbation. This strongly suggests that unpublished data exist or that clinical trials are seriously lacking for this common intervention. e‐1 imprecision. Confidence intervals include the possibility of important benefit and risk of harm. f‐1 indirectness. Studies mostly recruited from hospital or emergency department. Therefore this review may represent more severe exacerbations and does not apply to people attending the GP and requesting antibiotics. The review does not apply to people who have already received a course of antibiotics. One small study recruited children with status asthmaticus in 1974, when asthma management was different. g‐1 imprecision. Few events. h‐1 risk of bias. Study before good reporting standards introduced. Concerns over study, which excluded six participants, and it is not clear from which arm they were excluded. i‐1 indirectness. Participants were all children with status asthmaticus, and the study was conducted before current asthma management had been introduced (e.g. they all received IV adrenaline). j‐1 imprecision. One small study was included. | ||||||

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotics versus placebo/usual care, outcome: 1.3 Serious adverse events.

Antecedentes

Descripción de la afección

El asma es un trastorno inflamatorio crónico y frecuente que afecta las vías respiratorias. Se ha calculado que más de 300 000 000 de pacientes están afectados por asma en todo el mundo (GAN 2014). El síntoma predominante es la sibilancia, pero los pacientes con asma también presentan tos, opresión torácica y disnea. Hay variación en la gravedad de los síntomas, y habitualmente los síntomas son peores en la noche y temprano en la mañana (GINA 2017). El asma puede ser una afección muy debilitante para los adultos y los niños y aún es una causa importante de mortalidad. Sin embargo, los cambios inflamatorios en las vías respiratorias que se producen en el asma en general responden bien al tratamiento y son reversibles. Las recomendaciones actuales para el tratamientos de primera línea consisten en fármacos controladores (corticosteroides inhalados [CSI] con o sin beta2‐agonistas de acción prolongada [BAAP]) y fármacos para el alivio (BTS/SIGN 2016).

Un grupo de expertos ha propuesto la siguiente definición para una exacerbación del asma: "un empeoramiento del asma que requiere la administración de corticosteroides sistémicos para prevenir un resultado grave" (Fuhlbrigge 2012). Esta afirmación equipara una exacerbación con el empeoramiento de los síntomas y con la necesidad posterior de tratamiento más allá de la medicación habitual del paciente. Además, las exacerbaciones se pueden clasificar según su gravedad mediante una combinación de los antecedentes del paciente, los resultados del examen físico y los signos vitales (BTS/SIGN 2016). En general las exacerbaciones del asma son agudas y sus posibles causas subyacentes son múltiples. Es probable que la mayoría de las exacerbaciones sean multifactoriales, y las infecciones virales de las vías respiratorias están implicadas en muchos casos (Jackson 2011). Se considera que solo una minoría de las exacerbaciones del asma son desencadenadas por bacterias, aunque la evidencia es algo limitada y contradictoria (Papadopoulos 2011).

Las exacerbaciones del asma pueden ser graves y requerir tratamiento urgente. Si la exacerbación es grave, las guías recomiendan la administración de beta2‐agonistas de acción corta (BAAC) inhalados, tratamiento con corticosteroides sistémicos (orales o intravenosos) y bromuro de ipratropio y, en algunos casos, el sulfato de magnesio con oxígeno complementario para los pacientes que presentan hipoxemia. Los antibióticos se recomiendan solo cuando haya signos, síntomas o resultados de las pruebas de laboratorio claros que indiquen una infección bacteriana. (BTS/SIGN 2016).

Descripción de la intervención

"Los antibióticos son un tipo de antimicrobianos (que son) utilizados en el tratamiento o la prevención de las infecciones bacterianas" (Wikipedia). Los macrólidos son una clase de antibiótico que también muestran propiedades antiinflamatorias, lo que puede tener un efecto beneficioso adicional en los pacientes con asma.

La intervención que se examina es la administración de agentes antibióticos por cualquier vía (p.ej. por vía intravenosa [IV] u oral) a los pacientes que acuden a un profesional sanitario con diagnóstico de una exacerbación del asma, además de cualquier otro tratamiento que podrían recibir como parte de su atención. Los antibióticos se pueden administrar o prescribir en un contexto de atención primaria, si la exacerbación no fue lo bastante grave como para justificar el ingreso hospitalario inmediato, o en un servicio de urgencias (SU) o un ámbito hospitalario en el contexto de una exacerbación más grave. La duración habitual del tratamiento con antibióticos para la infección de las vías respiratorias varía de cinco a diez días (Public Health England). Es probable que los efectos secundarios sean específicos del antibiótico y varíen de bastante frecuentes y leves (p.ej. náuseas) a poco frecuentes y graves (p.ej. anafilaxia) (BNF).

De qué manera podría funcionar la intervención

Los antibióticos actúan contra las bacterias y funcionan a través de un mecanismo de acción bactericida o bacteriostático, y ambos ayudan al cuerpo a eliminar una infección bacteriana (Kohanski 2010). Si una infección bacteriana causa la exacerbación del asma, entonces la administración de un antibiótico apropiado puede dar lugar a la reducción de los síntomas y a una recuperación más rápida. Las infecciones bacterianas por microorganismos bacterianos atípicos como Mycoplasma pneumoniae y Chlamydophila pneumoniae se han asociado con las exacerbaciones agudas (Blasi 2007). Además, existen razones para la administración de macrólidos y posiblemente cetólidos en las exacerbaciones agudas debido a sus efectos antiinflamatorios concurrentes (Rollins 2010). Sin embargo, en una gran mayoría de los casos no se considera que la infección bacteriana sea la causa subyacente de la exacerbación aguda del asma; en estos casos, el paciente debería recibir poco beneficio de la administración de los antibióticos (Papadopoulos 2011). Además, la inmunidad bacteriana contra los antibióticos es un problema importante y puede reducir la eficacia del tratamiento con antibióticos para la infección bacteriana (Davies 2011).

Por qué es importante realizar esta revisión

Las guías actuales son claras con respecto a que, para los pacientes que presentan una exacerbación aguda del asma, la administración de antibióticos no debe ser habitual y que, en cambio, los antibióticos se deben prescribir solo si los signos y síntomas del paciente, como por ejemplo, la fiebre y el esputo purulento, indican que existe una infección bacteriana (BTS/SIGN 2016; Longmore 2014). El uso innecesario de los antibióticos pone al paciente en riesgo de eventos adversos relacionados con los antibióticos y aumenta la probabilidad de que se incremente la resistencia a los antibióticos, una inquietud global (Davies 2011).

La evidencia indica que un número significativo de médicos prescriben antibióticos de una manera mucho más amplia a los pacientes con una exacerbación del asma, en lugar de prescribirlos solo a los pacientes cuya presentación indica que tienen una infección bacteriana (Kozyrskyj 2006; Paul 2011; Vanderweil 2008). La aparente brecha entre las guías y la práctica clínica real, el gran número de pacientes tratados con antibióticos para las exacerbaciones agudas del asma y la creciente necesidad de una administración cuidadosa de los antibióticos, así como las consideraciones sobre los costes, destacan la importancia de proporcionar un resumen claro de la mejor evidencia disponible sobre la administración de los antibióticos para las exacerbaciones agudas del asma.

Esta revisión intenta aclarar la evidencia con respecto a la administración de antibióticos en los pacientes que se presentan con una exacerbación aguda del asma. Es una actualización de una revisión Cochrane anterior que se publicó por primera vez en 2001 y se actualizó por última vez en 2005 (Graham 2001). Hasta donde se conoce, ninguna otra revisión más reciente ha examinado este tema.

Objetivos

Determinar la eficacia y la seguridad de los antibióticos en el tratamiento de las exacerbaciones del asma.

Métodos

Criterios de inclusión de estudios para esta revisión

Tipos de estudios

Se incluyeron los ensayos controlados aleatorios (ECA) con un diseño de asignación al azar individual. Los ensayos aleatorios grupales fueron elegibles para inclusión, pero no se identificaron estudios que cumplieran los criterios de inclusión. Se incluyeron estudios informados como texto completo, publicados como resumen solo y datos no publicados. Se excluyeron los ensayos cruzados (crossover).

Tipos de participantes

Se incluyeron los estudios que reclutaron niños y adultos (18 años de edad o más) que acudieron al servicio de urgencias, la atención primaria, los consultorios de pacientes ambulatorios o las salas de hospitalización con una exacerbación del asma. Se incluyeron los estudios que reclutaron pacientes hospitalizados (que habían ingresado por una exacerbación del asma) y pacientes ambulatorios. Cuando los estudios incluyeron participantes de más de un contexto, se incluyeron los datos de los contextos relevantes, si se informaron por separado. Se excluyeron los estudios que reclutaron participantes con otros diagnósticos respiratorios como neumonía (confirmada por rayos X o diagnosticada clínicamente), enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) y bronquiectasia.

Tipos de intervenciones

Se incluyeron los estudios que compararon antibióticos con placebo o atención habitual, cuando la atención habitual no incluyó un antibiótico. Se incluyeron los estudios que administraron antibióticos intravenosos u orales, en cualquier dosis y durante cualquier duración del tratamiento. Se permitió cualquier cointervención, cuando no fue parte del tratamiento asignado al azar (p.ej. esteroides sistémicos, esteroides inhalados, beta2‐agonistas de acción larga o corta; bromuro de ipratropio, preparados de magnesio). Se excluyeron los estudios de antibióticos profilácticos (es decir, que no se iniciaron específicamente para el tratamiento de una exacerbación).

Tipos de medida de resultado

Resultados primarios

-

Ingreso en una unidad de cuidados intensivos/unidad de alta dependencia (UCI/UAD)

-

Duración de los síntomas/la exacerbación (medida por los investigadores a través de, por ejemplo, cuadernos diarios, puntuaciones de los síntomas y evaluaciones del tiempo hasta el regreso a las actividades normales)

-

Todos los eventos adversos/efectos secundarios

Resultados secundarios

-

Mortalidad

-

Duración del ingreso hospitalario

-

Recaída después de la presentación índice (como lo definieron los investigadores, por ejemplo, necesidad de antibióticos [adicionales], esteroides, ingreso o visitas para asistencia sanitaria no programadas)

-

Tasa de flujo espiratorio máximo (TFEM) (cambio a partir del valor inicial preferido)

El informe en el estudio de uno o más de los resultados enumerados en la presente no fue un criterio de inclusión para la revisión.

Métodos de búsqueda para la identificación de los estudios

Búsquedas electrónicas

We identified studies from the Cochrane Airways Trials Register, which is maintained by the Information Specialist for the Group. The Cochrane Airways Trials Register contains studies identified from several sources.

-

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) through the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (crso.cochrane.org).

-

Weekly searches of MEDLINE Ovid SP 1946 to date.

-

Weekly searches of Embase Ovid SP 1974 to date.

-

Monthly searches of PsycINFO Ovid SP 1967 to date.

-

Monthly searches of Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) EBSCO 1937 to date.

-

Monthly searches of Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED) EBSCO.

-

Handsearches of the proceedings of major respiratory conferences.

Studies contained in the Trials Register are identified through search strategies based on the scope of Cochrane Airways. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched conference proceedings, are provided in Appendix 1. See Appendix 2 for search terms used to identify studies for this review.

We searched the following trials registries.

-

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

-

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch).

We searched the Cochrane Airways Trials Register and additional sources from inception to October 2017, with no restriction on language of publication.

Búsqueda de otros recursos

We checked the reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We searched relevant manufacturers' websites for study information.

We searched for errata or retractions from included studies published in full text on PubMed on 10 November 2017.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Selección de los estudios

Three review authors (of BS, SW, RN, and ED) independently screened titles and abstracts of the search results and coded them as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. We retrieved the full‐text study reports of all potentially eligible studies, and three review authors (BS, SW, and RN) independently screened them for inclusion, recording reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We resolved disagreements through discussion. We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study, rather than each report, is the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table (Moher 2009).

Extracción y manejo de los datos

We used a data collection form that had been piloted on at least one study in the review to record study characteristics and outcome data. Two review authors (BS and SW) extracted the following study characteristics from included studies.

-

Methods: study design, total duration of study, details of any 'run‐in' period, number of study centres and locations, study setting, withdrawals, and date of study.

-

Participants: N, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, baseline lung function, smoking history, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria.

-

Interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant medications, and excluded medications.

-

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected and time points reported.

-

Notes: funding for studies and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Three review authors (BS, SW, and RN) then independently extracted outcome data from included studies. We noted in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table if outcome data were not reported in a usable way. We resolved disagreements by reaching consensus or by involving a third person (Chris Cates, Statistical Editor). One review author (RN) transferred data into the Review Manager file (Review Manager (RevMan)). We then double‐checked that data had been entered correctly by comparing data presented in the systematic review with data provided in the study reports. A second review author (RN) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the study report.

Evaluación del riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos

Two review authors (BS and SW) assessed risk of bias independently for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements through discussion and consultation with another review author (RN). We assessed risk of bias according to the following domains.

-

Random sequence generation.

-

Allocation concealment.

-

Blinding of participants and personnel.

-

Blinding of outcome assessment.

-

Incomplete outcome data.

-

Selective outcome reporting.

-

Other bias.

We judged each potential source of bias as presenting high, low, or unclear risk and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We then summarised risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for different key outcomes when necessary (e.g. for unblinded outcome assessment, risk of bias for all‐cause mortality may be very different than for a patient‐reported pain scale). When information on risk of bias relates to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for studies that contributed to that outcome

Medidas del efecto del tratamiento

We analysed dichotomous data as odds ratios (ORs) or risk differences (RDs) when events were rare. We analysed continuous data as mean differences (MDs). If data from rating scales were combined in a meta‐analysis, we ensured that they were entered with a consistent direction of effect (e.g. lower scores always indicate improvement).

We undertook meta‐analyses only when this was meaningful, that is, when treatments, participants, and the underlying clinical question were similar enough for pooling to make sense.

We described skewed data narratively (e.g. as medians and interquartile ranges for each group).

If we had identified single studies that reported multiple trial arms, we planned to include only the relevant arms. If two comparisons (e.g. drug A vs placebo and drug B vs placebo) had been combined in the same meta‐analysis, we planned to either combine the active arms or halve the control group to avoid double‐counting.

When adjusted analyses were available (ANOVA or ANCOVA), we used these as a preference in our meta‐analyses. If both change from baseline and endpoint scores were available for continuous data, we used change from baseline unless we noted a low correlation between measurements for individuals. If a study reported outcomes at multiple time points, we used the latest time point reported.

We used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) or 'full analysis set' analyses when reported (i.e. those for which data had been imputed for participants who were randomly assigned but did not complete the study) instead of completer or per‐protocol analyses.

Cuestiones relativas a la unidad de análisis

For dichotomous outcomes, we used participants, rather than events, as the unit of analysis. However, when rate ratios were reported in a study, we analysed them on this basis. We meta‐analysed data from cluster‐RCTs only if available data has been adjusted (or could be adjusted), to account for the clustering.

Manejo de los datos faltantes

We contacted investigators or study sponsors to verify key study characteristics and obtain missing numerical outcome data when possible (e.g. when a study is identified as an abstract only). When this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we took this into consideration when determining the GRADE rating for affected outcomes.

Evaluación de la heterogeneidad

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the studies in each analysis. We did not identify substantial heterogeneity in our analyses.

Evaluación de los sesgos de notificación

If we had been able to pool more than 10 studies, we planned to create and examine a funnel plot to explore possible small‐study and publication biases.

Síntesis de los datos

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table using all pre‐specified outcomes. We used the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it relates to studies that contributed data for the pre‐specified outcomes. We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), along with GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT). We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of studies by using footnotes and made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review when necessary.

Análisis de subgrupos e investigación de la heterogeneidad

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

-

Adults (aged 18 years) versus children.

-

Antibiotic type (macrolides versus other).

-

Setting: inpatient versus outpatient.

-

C‐reactive protein (CRP)‐stratified treatment versus non‐CRP‐stratified treatment.

We then planned to use the following outcomes in subgroup analyses.

-

ICU/HDU admission.

-

Duration of symptoms/exacerbation.

-

All adverse events/side effects.

We used the formal test for subgroup interactions provided in Review Manager (Review Manager (RevMan).

Análisis de sensibilidad

We planned to carry out the following sensitivity analyses while removing the following from the primary outcome analyses.

-

Excluding open‐label trials.

-

Excluding trials at high risk of selection bias.

-

Excluding unpublished data.

-

Comparing results from the fixed‐effect model versus results from the random‐effects model.

Results

Description of studies

Full details of the conduct and characteristics of each included study can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables, and reasons for exclusion when full texts had to be viewed are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Results of the search

This review is an update of a previous review (Graham 2001). We fully revised the protocol including background, PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes), and methods and registered the protocol on PROSPERO (Normansell 2017). Therefore we ran a new 'all years' search.

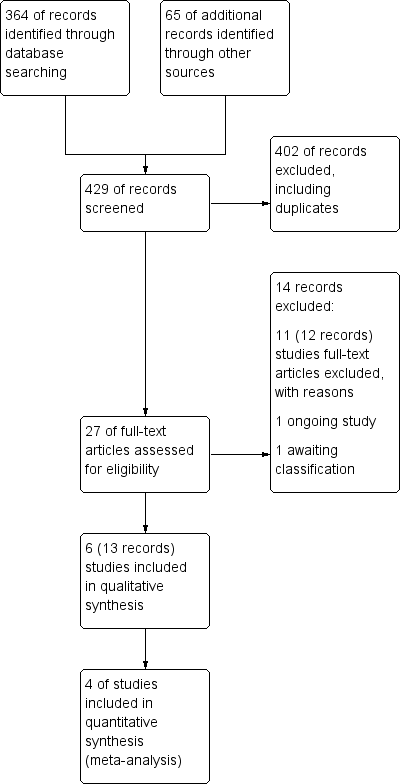

The preliminary searches conducted yielded a total of 429 references ‐ 364 from electronic database searches and 67 from records obtained through searches of clinicaltrials.gov and the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/). We excluded most (n = 402) of these references on the basis of the title and abstract. From these references, we identified 27 studies as potentially relevant. Six studies (for which there were 13 records) met the inclusion criteria for this review (Fonseca‐Aten 2006;Graham 1982;Johnston 2006;Johnston 2016; Koutsoubari 2012;Shapiro 1974), and we excluded the other 14 (see Excluded studies section). We have presented a study flow diagram in Figure 2. We conducted the latest search on 17 October 2017.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Six studies met our inclusion criteria, four of which contributed data to at least one meta‐analysis. These studies included a total of 681 participants who were randomly assigned to comparisons of interest in this review. The largest study included 278 participants (Johnston 2006), and the smallest 40 (Koutsoubari 2012). The mean total number of participants was 114, and the median number was 55. Investigators reported all six trials in full peer‐reviewed articles. We present a summary of the characteristics of included studies in Table 1.

| Study ID | Total n | Country | Age range (years) | Duration of follow‐up | Intervention comparison |

| 43 | USA | 4‐15 | 3‐8 weeks | Clarithromycin (15 mg/kg) vs placebo | |

| 71 | UK | 13‐82 | Unclear | Amoxicillin (300 mg 3 days) vs placebo | |

| 278 | International (multi‐centre) | 17‐68 | 6 weeks | Telithromycin (800 mg/d) vs placebo | |

| 199 | UK | Mean (SD) = 39.9 (14.82) | 6 weeks | Azithromycin (500 mg/d) vs placebo | |

| 40 | Greece | 6‐14 | 12 weeks | Clarithromycin (15 mg/kg/d for 3/52) vs placebo | |

| 50 | USA | 1‐18 | 7 days and 1 to 3 weeks | Hetacillin (ampicillin 100 mg/kg/24 h IV followed by 900 mg PO/d for 6/7) vs placebo |

We attempted to contact authors of Fonseca‐Aten 2006 for more information in July 2017 but were unable to make contact with the named contact person. The lead author of Johnston 2006 and the trial statistician for Johnston 2016 provided additional details on request.

Methods

As per our protocol, all included trials were RCTs, which individually randomised participants to antibiotics versus placebo or usual care. Five studies had post‐treatment follow‐up periods ranging from one to twelve weeks, and only one did not define a follow‐up period (Graham 1982). No study reported a run‐in period, as recruitment was triggered by an unscheduled presentation with an exacerbation. Outcome data were extracted at the end of antibiotic treatment or at the last time point reported. Two studies were conducted in the UK (Graham 1982;Johnston 2016), two in the USA (Fonseca‐Aten 2006; Shapiro 1974), one in Greece (Koutsoubari 2012), and the other (an international study) across multiple centres (Johnston 2006). Most of these studies recruited participants from the emergency department, from an urgent care setting, or when patients were admitted to hospital. One study recruited via parents bringing their children to them if an exacerbation was suspected, before subsequently attending hospital to confirm (Koutsoubari 2012).

Participants

We included studies involving both adults and children. Three studies recruited only children (age range 1 to 18, depending on the specific study (Fonseca‐Aten 2006; Koutsoubari 2012; Shapiro 1974)), two recruited only adults (age range 17 to 68, and 18 to 55 years; Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016), and one included adolescents and adults (age range 14 to 82; Graham 1982). Two studies included information on the ethnicity of participants. Most of those included were of white ethnicity (88.9% for the intervention arm and 94.6% for the control arm) in Johnston 2006, whilst the highest proportions of participants were of black ethnicity (68% and 48%, respectively) in Fonseca‐Aten 2006.

All studies included participants experiencing an asthma exacerbation, but how this was defined varied across the included studies. Of note, in Shapiro 1974, participants were given a diagnosis of "status asthmaticus" (defined as "a lack of response of severe bronchospasm to three subcutaneous injections of 1:1000 aqueous epinephrine given at 15‐minute intervals"). Three studies reported the asthma history of participants in the number of years since diagnosis, and only one reported the severity of asthma of participants and the severity of the exacerbation (Johnston 2016), although another also reported the current exacerbation severity index (Koutsoubari 2012). Both Johnston studies reported the smoking status and pack‐years of participants (Johnston 2006;Johnston 2016), Koutsoubari 2012 reported the percentage of participants exposed to tobacco smoke, and Graham 1982 reported the percentage of current smokers. It is interesting to note that Graham 1982 reported the proportion of participants who had received antibiotic treatment during the week before admission (24.3% in the treatment arm and 17.6% in the control arm); this was an exclusion criterion for most of the included studies.

All but one study explicitly excluded participants with a diagnosed, or strongly suspected, bacterial infection and those who had received recent antibiotic therapy (Koutsoubari 2012). Fonseca‐Aten 2006 excluded children with a diagnosis of bacterial infection needing antibiotics. Graham 1982 excluded participants whose chest X‐rays showed signs of pneumonia. Johnston 2006 excluded participants reporting any antibiotic use within 30 days before enrolment, or with an obvious infection requiring antibiotic treatment. Johnston 2016 excluded participants reporting use of oral or systemic antibiotics within 28 days before enrolment and participants requiring other antibiotic therapy. Finally, Shapiro 1974 excluded participants with evidence of bacterial disease, specifically, any of the following ‐ otitis media, purulent pharyngitis, or fever ‐ and lobular pulmonary infiltrate on admission chest X‐ray who recently received antibiotics.

Interventions

Four studies investigated macrolide antibiotics, with two trialling clarithromycin (Fonseca‐Aten 2006; Koutsoubari 2012), one azithromycin (Johnston 2016), and one telithromycin (part of the subgroup of macrolides known as ketolides) (Johnston 2006). The two remaining studies investigated penicillins, specifically, amoxicillin (Graham 1982) and hetacillin (known now as ampicillin) (Shapiro 1974). All studies compared the antibiotic of choice against a placebo, apart from Koutsoubari 2012, which was an open‐label study with usual care comparison. Both studies investigating clarithromycin were carried out in children and administered the antibiotic at the same dose (15 mg/kg/d). Doses used in each study are detailed in the summary of included studies (Table 1).

Outcomes

Outcomes reported were not consistent across the included studies. Lung function was the most consistently measured outcome, as reported by five of the six included studies. Most studies also reported some measure of participant symptoms at the end of treatment or follow‐up, or time taken for resolution of symptoms. Both Johnston 2006 and Johnston 2016 used an asthma symptom score. Graham 1982 and Shapiro 1974 reported duration of symptoms. Only half of the included studies reported adverse events, and only two explicitly reported serious adverse events (Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016).

Funding

Two trials were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies (Fonseca‐Aten 2006; Johnston 2006), two were funded by governmental agencies (Johnston 2016; Shapiro 1974), and the funding source for two studies was not reported (Graham 1982; Shapiro 1974).

Excluded studies

We excluded 14 records after full‐text assessment. We excluded 11 studies (12 records) with reasons as detailed in Characteristics of excluded studies. One trial is reported to be ongoing (NCT02003911). A further study is awaiting classification; this trial was registered on the EU clinical trials register in 2010, last refreshed on 20 September 2016, with status currently no longer recruiting. We were unable to identify a linked publication, and no contact details were given (EUCTR2010‐018592‐16‐DK). Nine of the excluded studies investigated long‐term use of antibiotics as prophylaxis for asthma rather than as treatment for exacerbations. One study investigated participants with chronic asthma, and another included participants with asthma‐like symptoms, rather than with confirmed asthma.

Risk of bias in included studies

We noted substantial variation in the levels of risk of bias between and within the studies included in this review. Moreover, although we judged few aspects of these studies to have high risk of bias, we found instances in studies when lack of detail on the precise methods used by study authors meant that the level of risk of bias was unclear. Figure 3 provides an overview of our risk of bias judgements.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We found three studies to have low risk of selection bias (Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016; Koutsoubari 2012), and three to have unclear risk (Fonseca‐Aten 2006; Graham 1982; Shapiro 1974). This lack of clarity was due to lack of detail on the exact methods used by study authors.

Blinding

One study used an open‐label design and therefore was at high risk of performance and detection bias (Koutsoubari 2012). All the other studies reported that they were double‐blinded (i.e. participants and personnel), and we considered them to be at low risk of performance bias. Only two studies provided sufficient detail on the method used to blind outcome assessors to indicate low risk of detection bias (Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016). For the other three studies, we judged the risk as unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

Studies varied in the level of risk of attrition bias. We judged Koutsoubari 2012 to be at low risk, as study authors stated that all randomised participants completed the trial. Two participants from the placebo group in Graham 1982 dropped out owing to slow clinical progress, but trialists describe including them in a sensitivity analysis under worst‐case scenario assumptions, which had no impact on the overall results. We therefore judged this study to be at low risk.

We judged Shapiro 1974 to be at high risk, as researchers excluded 6 of the 50 participants initially included: three because they developed signs and symptoms suggesting bacterial disease, and three because of inadvertent failure to administer the study preparation. The distribution between study arms of those excluded for suspected bacterial infection and for protocol violations is not reported. As the study was conducted over 40 years ago, we have not attempted to clarify this with the study authors. We also judged Fonseca‐Aten 2006 to be at high risk, as more than 50% of participants did not complete follow‐up; however, this study did not contribute outcome data to the review.

We considered Johnston 2006 to be at low risk of attrition bias for adverse events; 263 of 270 randomised participants were included in the safety analysis. Re‐inclusion of missing participants under best‐worst case assumptions and worst‐best case assumptions had little impact on the pooled effect estimate for all adverse events or for serious adverse events. More data for symptom scores and PEFR were missing (e.g. 240 out of 270 randomised provided day 10 symptom score data, and 253 out of 270 provided day 10 peak flow readings). We received detailed data tables and the statistical analysis plan from the lead study author. This confirms that missing end‐point PEFR data were imputed from a previous non‐baseline reading, if available. No baseline readings were carried forward. For missing domiciliary PEFR measurements, the average of previous and subsequent readings (if available) was used for imputation, and again, no baseline readings were carried forward. A similar approach was used to deal with missing symptom scores from patient diary cards. Given that we cannot be certain what impact the entirely missing values may have had on the final effect estimate, overall we rated this study as having unclear risk of bias.

We judged Johnston 2016 also to be at low risk for bias for adverse events; correspondence with the trial statistician confirmed that all randomised participants were included in the safety analysis. However, as with Johnston 2006, more data for other outcomes were missing. Twenty per cent of participants missed at least one study visit, 60 did not provide day 10 symptom score data, and 36 did not provide a day 10 peak flow reading. The trial statistician confirmed that mixed (multi‐level) modelling was used; thus all available diary records were included in the model, regardless of availability of the day 10 reading. It is unclear what impact the entirely missing values may have had on the effect estimates; therefore, results should be interpreted with caution. Overall, we judged this trial to be at unclear risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

For three studies, the level of risk of reporting bias was unclear. For one, there was low risk, and for two we judged the risk to be high.

We judged Fonseca‐Aten 2006 to be at high risk of reporting bias. We were not able to identify a prospective registration or published protocol, and we found that not all evaluated outcomes were reported numerically, for example, "No clinical differences were demonstrated for clarithromycin therapy vs placebo on visit 3". Attempts to contact study author teams failed. We also judged Shapiro 1974 to be at high risk; we found no prospective registration or protocol and determined that researchers did not evaluate all outcomes numerically (e.g. graphically displayed only), so we could not include these data in the meta‐analysis.

We judged Graham 1982 to be at unclear risk. Again, we were not able to identify a published protocol or a prospective registration, but study authors clearly reported all outcomes described in the methods section. However, study authors used medians and ranges and non‐parametric tests, so we could not combine data in meta‐analyses. Similarly, we were unable to identify a published protocol or registration for Koutsoubari 2012, but we found that study authors clearly reported all outcomes described in the methods. Study authors used medians and interquartile ranges for non‐normal data, so these were not combined in meta‐analyses.

We judged Johnston 2016 to be at low risk of reporting bias; the trial was prospectively registered and outcomes were reported as planned. Of note, the trial team relaxed the inclusion criteria in an attempt to improve recruitment, but this is unlikely to have introduced bias.

We judged Johnston 2006 to be at unclear risk of bias because several outcomes listed in the prospective trial registration were not fully reported, including outcomes of interest for this review (i.e. health status at follow‐up (6 weeks); need for additional medication (e.g. ICS, oral corticosteroid (OCS), bronchodilator); time to next exacerbation of asthma). The lead study author provided the following explanation: "the time‐to‐next‐acute‐exacerbation and need for additional medications data were not included because acquisition of such data in the setting of an acute exacerbation study, not unexpectedly, was so incomplete that a decision was taken not to analyse them".

Other potential sources of bias

In Graham 1982, participants could be included more than once in the trial, as the episode, rather than the individual, was the unit of randomisation: 60 patients experienced 71 exacerbations during the trial. We are unable to determine what effect this had on the effect estimates reported. We detected baseline imbalance between arms in Shapiro 1974, including differences in the mean number of days of wheezing before admission (2.6 in the hetacillin group and 5.8 in the placebo group).

Effects of interventions

Intensive care unit/high dependency unit admission

Children

One child in the placebo group of Shapiro 1974 experienced respiratory arrest shortly after admission and was mechanically ventilated; we assume this child would have received care in an ICU/HDU setting. Of note, this study was conducted in children with status asthmaticus. None of the other included studies reported this outcome.

Duration of symptoms/exacerbation

No studies reported on the duration of symptoms or exacerbations, which was our pre‐specified outcome. However, four studies used different approaches to report asthma symptoms (Graham 1982; Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016; Koutsoubari 2012).

Adults

Graham 1982 reported a physician's assessment of asthma symptoms at hospital discharge (median duration of admission seven days in the amoxicillin group and eight days in the placebo group) on a 4 to 12‐point scale (higher score = worse symptoms) with results presented as medians and ranges. The median (range) score in the amoxicillin group was 5 (4 to 9), and in the placebo group 4 (4 to 8) (n = 69). The same study reported patients' assessment of symptoms at discharge on a visual analogue scale (lower score = worse symptoms), also as medians and ranges. The median (range) score in the amoxicillin group was 33 (range 0 to 250), and in the placebo group 28 (0 to 85) (n = 69). The visual analogue scale was reported to be 10 cm and the results given in millimetres; as the trial was conducted in 1982, we did not attempt to resolve the discrepancy that the range reported exceeds the scale. The between‐group difference for both scores was reported as non‐significant. Graham 1982 also reported the median and range of numbers of days to 50% improvement in symptoms as assessed by both physician and patient. In the amoxicillin group, the median (range) numbers of days was 3 (1 to 6) for the physician assessment and 3 (2 to 10) in the placebo group. For patients' assessment, the scores were 2 (2 to 10) and 2 (2 to 8), respectively.

Participants in Johnston 2006 (a trial of telithromycin) and Johnston 2016 (a trial of azithromycin) were asked to rate their own symptoms using modified diary cards on a 7‐point scale (0 = no symptoms, 6 = severe symptoms). We were able to extract data at 10 days and at six weeks from Johnston 2006, and at 10 days from Johnston 2016. We chose to combine the 10‐day findings using mean differences. Results favour antibiotics over placebo (mean difference (MD) ‐0.34, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.60 to ‐0.08; participants = 416; I2= 0%; studies = 2; Analysis 1.1; moderate‐quality evidence). At six weeks, participants in the intervention group of Johnston 2006 still reported lower symptom scores than those in the control group, but the upper confidence interval includes no between‐group difference (MD ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐0.5 to 0.02; P = 0.066). Johnston 2006 also reported the number of symptom‐free days as a percentage at 10 days (calculated by dividing the number of days when all symptom scores in the diary were zero by the number of days for which the patient provided scores); results favoured telithromycin (16% of days symptom‐free vs 8%; P = 0.006; participants = 255).

Children

Koutsoubari 2012 reported the median and the interquartile range (IQR) for symptom‐free days at 3, 6, and 12 weeks. At 3 weeks, the median (IQR) for the clarithromycin group was 16 (1), and for the control group 12 (2) (n = 40). At 6 weeks, values were reported as 36 (2) and 29 (3), respectively (n = 40), and by 12 weeks, 78 (2) and 69 (6), respectively (n = 40) (P < 0.0001 at all three time points). The same study reported the duration in days of the index asthma exacerbation, also as median and IQR. The median (IQR) in the clarithromycin group was 5 (1), and in the control group 7.5 (1) (n = 40) (P < 0.00001).

All adverse events/side effects

Four studies reported adverse events (Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016; Koutsoubari 2012; Shapiro 1974). We combined data for all adverse events (AEs) from three studies; the confidence interval includes both potential harm or benefit of the intervention (odds ratio (OR) 0.99, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.43; participants = 506; studies = 3; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2). Researchers reported no significant difference in the test for subgroup differences between adults and children.

We also combined data for serious adverse events (SAEs). We were able to extract data from three studies, and we analysed the result as a risk difference because events were rare. The pooled result suggests no difference between antibiotic and control, but it should be noted that only 10 events were reported across the three trials (five in the antibiotic group and five in the placebo group) (risk difference (RD) 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.03; participants = 502; studies = 3; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.3). Study results show no significant difference in the test for subgroup differences between adults and children.

Adults

Pooled data for the adults subgroup were as follows: OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.45.

Children

Shapiro 1974 also reported 'complications' after discharge and noted two in the hetacillin group (one hospitalisation for asthma, and one participant experienced persistent wheezing) and three in the placebo group (fever, diarrhoea, and pulmonary infiltrate in one participants, abdominal discomfort in another, and persistent wheezing in a third).

For serious adverse events, Koutsoubari 2012 reported that no participant required hospital admission during the study; as the definition of a serious adverse event is "death, a life‐threatening adverse event, inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation", we assumed that no participant had experienced an SAE.

Mortality

No deaths were reported in any of the included studies.

Length of hospital admission

Two studies reported admission duration, but we could not combine the results (Graham 1982; Shapiro 1974).

Adults

Graham 1982 reported median (range) duration of admission in days as 7 (3 to 25) in the amoxicillin group and 8 (3 to 6) in the placebo group (n = 69; reported as not significantly different).

Children

Shapiro 1974 reported the mean (SD) duration of admission; the confidence interval includes the possibility of an increase or a decrease in duration of admission in the hetacillin group (MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.53 to 0.33; participants = 43; studies = 1; very low‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.4).

Relapse after index presentation

One study reported exacerbations in the follow‐up period (Johnston 2006). Two adults in each arm experienced an exacerbation by the six‐week time points (n = 263).

Peak expiratory flow rate

Four studies reported peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) (Graham 1982; Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016; Koutsoubari 2012).

Adults

We combined endpoint results at 10 days for Johnston 2006 and Johnston 2016 using generic inverse variance (GIV). The result favours antibiotics over placebo with the mean difference exceeding the minimal clinically important difference of 18.79 L/min (Santanello 1999): MD 23.42 L/min, 95% CI 5.23 to 41.60; participants = 416; studies = 2; Analysis 1.5. However, the pre‐specified primary outcome in Johnston 2006 was change in domiciliary morning PEFR. Based on modelled data, the mean difference between groups in the change from baseline was reported as 3.6 L/min (95% CI ‐32.5 to 25.3; P = 0.81).

Children

One study in children reported the maximum peak flow recorded during the follow‐up period (Koutsoubari 2012); results favoured the clarithromycin group, but the confidence interval includes no difference (MD 38.80, 95% CI ‐11.19 to 88.79; participants = 40; studies = 1; Analysis 1.6).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was restricted by the small number of trials identified.

Adults (aged 18 years) versus children

Data for adults and children were subgrouped throughout and were reported separately above. Only two meta‐analyses pooled data from adults and children: serious adverse events and all adverse events. No serious events were reported in the one study in children, and the test for subgroup differences was negative (P = 0.99; I2 = 0%). Similarly for all adverse events, no subgroup difference was detected (P = 0.80; I2 = 0%).

Antibiotic type (macrolides vs other)

Only one meta‐analysis pooled data from two different classes of antibiotic: all adverse events. We detected no difference between the two studies investigating a macrolide antibiotic and the one study investigating a penicillin (P = 0.80; I2 = 0%) (analysis not shown); however, the one study investigating penicillin was conducted in 1974, and the two investigating macrolides in 2006 and 2016.

Setting: inpatient versus outpatient

Most of the participants included in this review were recruited in a hospital or emergency department setting. Two trials reported recruiting some participants from urgent care or primary care centres but did not present data disaggregated by setting (Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016).

CRP‐stratified treatment versus non‐CRP‐stratified treatment

None of the included studies reported stratifying treatment by CRP results.

Sensitivity analysis

Excluding open‐label trials

Only one study was reported to be open‐label (Koutsoubari 2012). This study was combined with other studies in one analysis (serious adverse events) but did not contribute events; thus its exclusion has no impact on the effect estimate.

Excluding trials at high risk of selection bias

We did not judge any of the included trials to be at high risk of selection bias. Three trials were at unclear risk for both random sequence generation and allocation concealment, but only one trial contributed to a meta‐analysis (Shapiro 1974): all adverse events. Excluding this trial had minimal impact on the effect estimate (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.45; participants = 462; studies = 2; I2 = 0%; data not shown).

Excluding unpublished data

We did not include any unpublished data in our meta‐analyses.

Comparing results from the fixed‐effect model versus the random‐effects model

Results show a negligible difference between random‐effects and fixed‐effect models.

Discusión

Resumen de los resultados principales

Esta revisión es una actualización de una revisión anterior (Graham 2001) y se realizó una nueva búsqueda de "todos los años". Se examinó completamente el protocolo, incluidos los antecedentes, la pregunta PICO (población, intervención, comparación, resultados) y los métodos, y se registró en PROSPERO (Normansell 2017). Seis estudios cumplieron los criterios de inclusión, y cuatro contribuyeron con datos a al menos un metanálisis. Estos estudios incluyeron 681 adultos y niños que se asignaron al azar a las comparaciones de interés de esta revisión. Cuatro estudios investigaron antibióticos macrólidos (Fonseca‐Aten 2006; Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016; Koutsoubari 2012) y dos estudios investigaron ampicilina y amoxicilina, respectivamente (Graham 1982; Shapiro 1974); ambos estudios se realizaron hace más de 30 años. Cinco estudios compararon antibióticos versus placebo, y uno fue abierto (Koutsoubari 2012). Fue posible realizar un metanálisis limitado debido al número pequeño de ensayos identificados y a la heterogeneidad entre los estudios.

Ninguno de los estudios incluidos informó el ingreso a la unidad de cuidados intensivos/unidad de alta dependencia (UCI/UAD), aunque un participante en el grupo placebo de Shapiro 1974 (un estudio que incluyó niños con estado asmático) presentó un paro respiratorio poco después del ingreso y se ventiló mecánicamente. Ninguno de los estudios incluidos informó el resultado de interés duración de los síntomas. Los estudios proporcionaron algunos datos sobre las puntuaciones de los síntomas, y cuatro estudios informaron alguna medida de los días sin síntomas. En general favorecieron a los antibióticos, pero las medidas muestran ambigüedad.

No se informaron muertes en ninguno de los estudios incluidos. Cuatro estudios informaron eventos adversos, y fue posible combinar los datos para los eventos adversos graves de tres estudios, pero fueron poco frecuentes; Solo se informaron diez eventos entre los tres ensayos (cinco en el grupo de antibiótico y cinco en el grupo placebo; 502 participantes): diferencia de riesgos (DR) 0,00; intervalo de confianza (IC) del 95%: ‐0,03 a 0,03. Se combinaron los datos para todos los eventos adversos (EA) de tres estudios; el intervalo de confianza incluye un posible daño o beneficio de la intervención: odds ratio (OR) 0,99; IC del 95%: 0,69 a 1,43.

Un estudio informó las exacerbaciones en el período de seguimiento (Johnston 2006). Se informó que dos participantes en cada brazo presentaron una exacerbación en el transcurso de seis semanas (n = 263). Cuatro estudios informaron la tasa de flujo espiratorio máximo (TFEM). Se combinaron los resultados de las variables principales de evaluación a los diez días para Johnston 2006 y Johnston 2016 y los resultados favorecieron a los antibióticos sobre placebo, con una diferencia de medias (DM) que excedió la diferencia mínima clínicamente importante: diferencia de medias (DM) 23,42 l/min, IC del 95%: 5,23 a 41,60. Un estudio en niños informó el flujo máximo registrado durante el período de seguimiento (Koutsoubari 2012); los resultados favorecieron al grupo de claritromicina, pero el intervalo de confianza no incluyó ninguna diferencia: DM 38,80; IC del 95%: ‐11,19 a 88,79. Los tres estudios que informaron la TFEM utilizaron antibióticos macrólidos, por lo que la reducción del flujo máximo podría haberse debido al menos en parte a las propiedades antiinflamatorias.

Solo fue posible realizar análisis de subgrupos y de sensibilidad muy limitados debido al número pequeño de ensayos identificados, y no se encontró evidencia de una modificación importante del efecto según la edad o la clase de antibiótico, aunque no fue posible descartarla.

Compleción y aplicabilidad general de las pruebas

La evidencia presentada se considera incompleta debido al número pequeño de ensayos relevantes identificados, la heterogeneidad entre los estudios que limitó el metanálisis y la antigüedad de dos de los seis estudios, un ensayo controlado aleatorio (ECA) se realizó en 1974 (Shapiro 1974) y otro en 1982 (Graham 1982). La aplicabilidad de la evidencia de los ECA realizados hace más de 30 años es dudosa. Por ejemplo, Shapiro 1974 utilizó una definición de exacerbación aguda del asma que difiere de la utilizada en la práctica actual; además los informes muestran diferencias entre el protocolo de tratamiento y las guías actuales para el tratamiento de los pacientes con exacerbaciones agudas del asma. De manera adicional, la mayoría de los participantes se reclutaron en un hospital, en lugar de en un contexto de atención primaria, lo que puede limitar la generalizabilidad a otros contextos, por ejemplo, la atención primaria.

Solo cuatro de los seis estudios incluidos contribuyeron al metanálisis. Una gran parte de los datos no se presentó en los artículos de los estudios en un formato compatible con los otros estudios, o sencillamente no se informaron. El estudio Fonseca‐Aten 2006 no incluyó datos clínicos en sus resultados. Es evidente la considerable heterogeneidad entre los resultados informados en estos estudios. Esta discrepancia entre los resultados dificultó realizar muchos metanálisis significativos, lo que limita la completitud de la evidencia presentada. No se intentó abordar los efectos beneficiosos o perjudiciales de la administración de antibióticos a largo plazo en el asma, que es el tema de otra revisión (Kew 2015).

Cinco de los seis estudios incluidos en esta revisión excluyeron específicamente a los pacientes con diagnóstico de una infección bacteriana, o si existía una sospecha firme. En consecuencia, la aplicación de los resultados de la revisión se limita a los pacientes con una exacerbación del asma sin signos, síntomas o hallazgos en las investigaciones que indiquen una infección bacteriana (es decir, los que se ajustan a las guías actuales para recibir antibióticos). Sin embargo, se consideraría poco ético no administrarle antibióticos a un paciente que se considera que es probable que presente una infección bacteriana; por lo tanto, es poco probable que los estudios actuales y futuros aborden esta pregunta. Además, aunque los estudios incluidos que reclutaron adultos excluyeron a los pacientes con otras comorbilidades respiratorias, como la enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) o el "síndrome superpuesto de EPOC‐asma" (ACOS, por sus siglas en inglés), esta afección puede ser más difícil de diagnosticar; por lo tanto, es posible que los ensayos en adultos incluyeran a pacientes con este diagnóstico, lo que pudiera ser potencialmente un factor de confusión para los resultados de los estudios (Soriano 2003). Aunque ninguno de los estudios incluidos presentó resultados estratificados por los antecedentes de tabaquismo, los dos estudios más grandes incluidos en adultos excluyeron a los participantes con antecedentes de tabaquismo mayor de diez o cinco paquetes al año, respectivamente (Johnston 2006; Johnston 2016).

Una observación relevante que surgió de esta revisión se relaciona con la dificultad para el reclutamiento de los participantes que se señala en Johnston 2016. Los investigadores pudieron reclutar a solo 199 participantes de 4582 evaluados, y excluyeron a 2044 porque recibieron tratamiento previo con antibióticos. Por cada paciente asignado al azar, al menos diez pacientes se excluyeron por este motivo. Lo anterior indica que la administración de antibióticos puede estar generalizada en el Reino Unido, posiblemente en contra de las guías actuales (BTS/SIGN 2016). Las guías declaran con claridad que los antibióticos no se deben utilizar para el tratamiento habitual de las exacerbaciones agudas del asma (BTS/SIGN 2016; GINA 2017). Los investigadores han encontrado evidencia que indica niveles altos de prescripción de antibióticos para las exacerbaciones agudas del asma. En los Estados Unidos, un estudio informó que alcanza hasta el 60% (Lindenauer 2016); de manera similar, un estudio en China informó que casi el 75% de los pacientes asistieron al servicio de urgencias por una exacerbación aguda y recibieron un antibiótico (Tang 2013); la cifra equivalente de un estudio realizado en el Reino Unido fue 57% (Bafadhel 2011). Estas cifras plantean un reto para los investigadores que intentan realizar estudios que examinen la eficacia y la seguridad de los antibióticos para las exacerbaciones agudas del asma.

Una complicación adicional para la interpretación es que cualquier efecto beneficioso moderado asociado con la administración de los macrólidos puede ser resultado de las propiedades antiinflamatorias, en lugar de las propiedades antibacterianas de esta clase de antibióticos (Rollins 2010). Los estudios directos que comparen las clases de antibióticos tendrían un uso limitado para resolver esta incertidumbre, ya que habría un factor de confusión relacionado con los diferentes espectros de bacterias contra las cuales son eficaces los antibióticos. Si se hubieran identificado más estudios, habría sido necesario considerar si el agrupamiento de los estudios que utilizaron antibióticos penicilinas con los estudios más recientes que utilizaron macrólidos tendría sentido clínico. Sin embargo, el único metanálisis en el que ocurrió lo anterior fue el de todos los eventos adversos, en el que los dos ensayos recientes de Johnston que utilizaron macrólidos se agruparon con un estudio anterior que utilizó ampicilina. La evidencia para las diferencias de subgrupos de este metanálisis es negativa, pero con poco poder estadístico. Los aspectos relacionados con el agrupamiento apropiado pueden hacerse más relevantes en las actualizaciones futuras de esta revisión, si se identifican ensayos adicionales.

Finalmente, se debe señalar que ninguno de los pacientes se incluyó sobre la base de marcadores inflamatorios como la proteína C reactiva (PCR) o la procalcitonina, aunque la evidencia indica que estos marcadores se utilizaron para lograr un efecto beneficioso sobre la reducción de la prescripción de antibióticos en los pacientes con asma (Long 2014). Habitualmente el acceso a las pruebas para confirmar una infección bacteriana no está disponible para todos los médicos en todo el mundo, en especial en un contexto de atención primaria. Además, ningún estudio proporcionó información sobre los costes, y ninguno exploró los posibles problemas que surgen de la resistencia a los antibióticos.

Calidad de la evidencia

La calificación de la calidad de los resultados varió de moderada a muy baja. La certeza se redujo para todos los resultados debido a la sospecha de sesgo de publicación; a pesar de la disponibilidad de un tratamiento común para el asma, solo se identificaron seis ECA elegibles, lo que indica que pueden existir datos no publicados. Sin embargo, no fue posible explorar formalmente este hallazgo mediante un gráfico en embudo (funnel plot) porque se identificó un número insuficiente de estudios. La certeza disminuyó aún más debido a la indireccionalidad; la mayoría de los ensayos incluidos reclutaron pacientes de contextos de atención de urgencias, lo que limita la aplicabilidad para los contextos de atención primaria, que es donde acuden inicialmente muchos pacientes con exacerbaciones agudas del asma. Este problema se vio agravado por el ensayo más reciente (Johnston 2016), que tuvo grandes dificultades para reclutar suficientes participantes porque muchos pacientes ya habían recibido un ciclo de antibióticos en el momento en el que acudieron al servicio de urgencias, por lo que se excluyeron. Además, la calidad se disminuyó por la indireccionalidad debido a la antigüedad de dos de los seis estudios. La imprecisión afectó a los resultados eventos adversos (números pequeños de eventos y contribuyeron pocos ensayos) y duración de la estancia hospitalaria. Finalmente, surgieron inquietudes por el riesgo de sesgo relacionado con la falta de cegamiento en los resultados a los que contribuyó Koutsoubari 2012. También hubo inquietudes por el informe poco claro de los métodos de los ensayos para los resultados a los que contribuyeron los dos ensayos más antiguos; dichos ensayos se realizaron en un momento en el que la práctica metodológica para la realización de los ensayos puede haber sido menos rigurosa, y en el que la atención del asma era diferente (Graham 1982; Shapiro 1974).

Sesgos potenciales en el proceso de revisión

Esta revisión se realizó en conformidad con las normas Cochrane y se siguió un protocolo publicado previamente (Normansell 2017). Un editor del Grupo Cochrane de Vías Respiratorias examinó el protocolo, pero no fue formalmente revisado por pares.

Acuerdos y desacuerdos con otros estudios o revisiones

La búsqueda bibliográfica solo identificó una revisión sistemática que comparó antibióticos con placebo para las exacerbaciones agudas del asma, y fue la versión anterior de esta revisión Cochrane (Graham 2001). Esta revisión no encontró datos significativos para contradecir la recomendación de las BTS Guidelines for Asthma 2016 y las GINA 2017 Guidelines, que recomiendan no administrar antibióticos de manera habitual en las exacerbaciones agudas del asma (BTS/SIGN 2016; GINA 2017).

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotics versus placebo/usual care, outcome: 1.3 Serious adverse events.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo/usual care, Outcome 1 Symptom score.

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo/usual care, Outcome 2 All adverse events.

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo/usual care, Outcome 3 Serious adverse events.

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo/usual care, Outcome 4 Length of hospital stay (days).

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo/usual care, Outcome 5 PEF (GIV).

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo/usual care, Outcome 6 PEF.

| Antibiotics compared to placebo/usual care for acute asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute asthma exacerbation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo/usual care | Risk with antibiotics | |||||