Corticosteroides inhalados versus sistémicos para prevenir la displasia broncopulmonar en neonatos prematuros ventilados de muy bajo peso al nacer

Resumen

Antecedentes

La displasia broncopulmonar (DBP) sigue siendo una causa importante de mortalidad y morbilidad en los lactantes prematuros y la inflamación desempeña un papel significativo en su patogénesis. El uso de corticosteroides inhalados puede modular el proceso inflamatorio sin que haya concentraciones elevadas de corticosteroides sistémicos concomitantes y con un menor riesgo de efectos adversos. Esta es una actualización de una revisión publicada en 2012 (Shah 2012). Recientemente se actualizó la revisión relacionada sobre «Corticosteroides inhalados versus corticosteroides sistémicos para el tratamiento de la displasia broncopulmonar en neonatos prematuros de muy bajo peso al nacer sometidos a ventilación».

Objetivos

Determinar el efecto de los corticosteroides inhalados frente a los corticosteroides sistémicos iniciados en los primeros siete días de vida para prevenir la muerte o la DPB en lactantes ventilados de muy bajo peso al nacer.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se utilizó la estrategia de búsqueda estándar del Grupo Cochrane de Neonatología para buscar en el Registro Cochrane Central de Ensayos Controlados (CENTRAL 2017, número 1), MEDLINE vía PubMed (1966 hasta el 23 de febrero 2017), Embase (1980 hasta el 23 de febrero 2017) y en CINAHL (1982 hasta el 23 de febrero 2017). También se buscaron ensayos controlados aleatorizados (ECA) y ensayos cuasialeatorizados en registros de ensayos clínicos, resúmenes de congresos y listas de referencias de los artículos recuperados.

Criterios de selección

Ensayos controlados aleatorizados o cuasialeatorios que compararan el tratamiento con corticosteroides inhalados versus sistémicos (independientemente de la dosis y la duración) iniciado en los primeros siete días de vida en lactantes prematuros de muy bajo peso al nacer sometidos a ventilación asistida.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Los datos de los resultados clínicos se extrajeron y analizaron utilizando Review Manager. Cuando fue apropiado, se realizó un metanálisis con el riesgo relativo (RR) típico, la diferencia de riesgos (DR) típica y la diferencia de medias ponderada (DMP). Se realizaron metanálisis con el riesgo relativo típico, la diferencia de riesgos (DR) típica y la diferencia de medias ponderada con sus intervalos de confianza (IC) del 95%. Cuando la DR era estadísticamente significativa, se calculó el número necesario para beneficiar o el número necesario para dañar. La calidad de la evidencia se evaluó con los criterios GRADE.

Resultados principales

Se incluyeron dos ensayos con 294 niños. No se incluyeron estudios nuevos para la actualización de 2017. La incidencia de muerte o de DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual no presentó diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los lactantes que recibieron corticosteroides inhalados o sistémicos (RR 1,09; IC del 95%: 0,88 a 1,35; DR 0,05; IC del 95%: ‐0,07 a 0,16; 1 ensayo, N = 278). La incidencia de DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual entre los supervivientes no fue estadísticamente significativa entre los grupos (RR 1,34; IC del 95%: 0,94 a 1,90; DR 0,11; IC del 95%: ‐0,02 a 0,24; 1 ensayo, N = 206). No hubo ninguna diferencia estadísticamente significativa en los resultados de la DBP a los 28 días, la muerte a los 28 días o a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual y el resultado combinado de la muerte o la DBP a los 28 días entre los grupos (2 ensayos, N = 294). La duración de la ventilación mecánica fue significativamente mayor en el grupo de corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con el grupo de corticosteroides sistémicos (DM típica 4 días, IC del 95%: 0,2 a 8; 2 ensayos, N = 294; I² = 0%), así como la duración de la administración de oxígeno suplementario (DM típica 11 días, IC del 95%: 2 a 20; 2 ensayos, N = 294; I² = 33%).

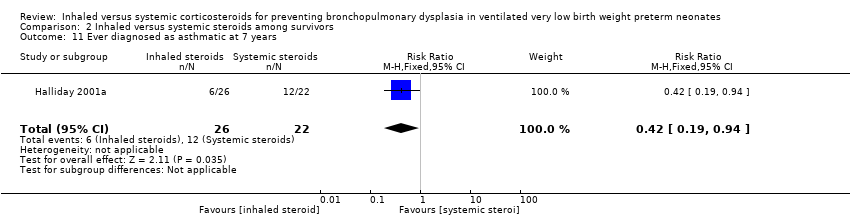

La incidencia de hiperglucemia fue significativamente menor con los corticosteroides inhalados (RR 0,52; IC del 95%: 0,39 a 0,71; DR ‐0,25; IC del 95%: ‐0,37 a ‐0,14; 1 ensayo, N = 278; NNTB 4; IC del 95%: 3 a 7 para evitar que un lactante experimente hiperglucemia). La tasa de conducto arterioso persistente aumentó en el grupo que recibió corticosteroides inhalados (RR 1,64; IC del 95%: 1,23 a 2,17; DR 0,21; IC del 95%: 0,10 a 0,33; 1 ensayo, N = 278; NNTD 5; IC del 95%: 3 a 10). En un subconjunto de lactantes supervivientes del Reino Unido e Irlanda no hubo diferencias significativas en los resultados del desarrollo a los siete años de edad. Sin embargo, hubo una reducción del riesgo de haber sido diagnosticado como asmático a los siete años de edad en el grupo de corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con el grupo de corticosteroides sistémicos (N = 48) (RR 0,42; IC del 95%: 0,19 a 0,94; DR ‐0,31; IC del 95%: ‐0,58 a ‐0,05; NNTB 3; IC del 95%: 2 a 20).

Según los criterios GRADE, la calidad de la evidencia fue de moderada a baja. La calidad de la evidencia se disminuyó sobre la base del diseño (riesgo de sesgo), la congruencia (heterogeneidad) y la precisión de las estimaciones.

Ambos estudios recibieron apoyo financiero y la industria farmacéutica proporcionó aerocámaras e inhaladores de dosis medidas de budesonida y placebo para el estudio más grande. No se identificó ningún conflicto de interés.

Conclusiones de los autores

No se encontró evidencia de que los corticosteroides inhalados de forma temprana otorgaran ventajas importantes sobre los corticosteroides sistémicos en el tratamiento de los lactantes prematuros dependientes del respirador. Sobre la base de esta revisión, los corticosteroides inhalados no pueden recomendarse sobre los corticosteroides sistémicos como parte de la práctica estándar para los recién nacidos prematuros ventilados. Debido a que podrían tener menos efectos adversos que los corticosteroides sistémicos, se necesitan más ensayos controlados aleatorizados sobre los corticosteroides inhalados que consideren el cociente riesgo:beneficio de las diferentes técnicas de administración, los esquemas de dosificación y los efectos de largo plazo, con particular atención a los resultados del desarrollo neurológico.

PICO

Resumen en términos sencillos

Corticosteroides inhalados versus sistémicos para prevenir la neumopatía crónica en neonatos prematuros ventilados de muy bajo peso al nacer

Pregunta de la revisión

El objetivo principal era comparar la efectividad de los corticosteroides inhalados frente a los corticosteroides sistémicos iniciados en la primera semana de vida para prevenir la muerte o la displasia broncopulmonar (definida como la necesidad de oxígeno suplementario a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual) en los lactantes sometidos a ventilación mecánica invasiva con un peso al nacer ≤ 1500 g o una edad gestacional ≤ 32 semanas.

Antecedentes

Los bebés prematuros que requieren apoyo respiratorio a menudo desarrollan displasia broncopulmonar. Se piensa que parte de la causa puede residir en la inflamación de los pulmones. Los corticosteroides, cuando se administran por vía oral o intravenosa, reducen esta inflamación, aunque se asocian a efectos secundarios graves. El uso de corticosteroides se ha asociado con parálisis cerebral (problema motor) y con un retraso en el desarrollo. Es posible que con la inhalación de los corticosteroides se puedan reducir los efectos adversos, dado que el fármaco llega directamente al pulmón.

Características de los estudios

La revisión consideró los ensayos que comparaban a los recién nacidos prematuros que recibieron corticosteroides por inhalación con los que recibieron corticosteroides de forma sistémica (a través de una vena o por vía oral) mientras recibían ventilación mecánica. Se incluyeron dos ensayos con 294 niños. Un estudio incluyó a 278 lactantes y el otro estudio incluyó a 16 lactantes. No se incluyeron estudios nuevos para la actualización de 2017.

Ambos estudios recibieron apoyo financiero y la industria farmacéutica proporcionó aerocámaras e inhaladores de dosis medidas de budesonida y placebo para el estudio más grande. No se identificó ningún conflicto de interés.

Resultados clave

No hubo evidencia de que la inhalación de corticosteroides en comparación con los corticosteroides sistémicos previniera el resultado primario de la muerte o la displasia broncopulmonar. El número de días que el niño necesitó apoyo con ventilación mecánica u oxígeno adicional aumentó en los lactantes que recibieron corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con los lactantes que recibieron corticosteroides sistémicos. Estos resultados se informaron en ambos ensayos. La tasa de conducto arterioso persistente (fallo del conducto arterioso, una derivación arterial en la vida del feto, que se cierra después del nacimiento) aumentó en el grupo que recibió corticosteroides inhalados. Hubo una menor incidencia de niveles altos de azúcar en la sangre en el grupo de corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con el grupo de corticosteroides sistémicos. Estos resultados secundarios se presentaron solo en un ensayo (el ensayo más grande). En una submuestra de 52 niños de siete años de edad, no hubo diferencias en los resultados del seguimiento a largo plazo entre el grupo de corticosteroides inhalados y el de corticosteroides sistémicos. En una muestra aún más pequeña de 48 niños el resultado de «alguna vez diagnosticado como asmático alrededor de los siete años de edad» fue significativamente menor en el grupo de corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con el grupo de corticosteroides sistémicos.

Calidad de la evidencia

Según los criterios GRADE, la calidad de la evidencia fue de moderada a baja.

Conclusiones de los autores

Summary of findings

| Inhaled steroids compared with systemic corticosteroids for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia among all randomised infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: Preterm neonates with respiratory distress Settings: NICU Intervention: Inhaled steroids Comparison: Systemic steroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic steroids | Inhaled steroids | |||||

| Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age among all randomised | 526 per 1000 | 573 per 1000 | RR 1.09 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.35) | 278 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for this single study was high. The study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| Death or BPD at 28 days | 736 per 1000 | 780 per 1000 | RR 1.05 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.20) | 294 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for these two studies was high. The larger study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. The smaller study was not blinded and it was stopped prematurely. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Heterogeneity/Consistency: There was high heterogeneity for this analysis I² = 78%. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age | 237 per 1000 | 343 per 1000 | RR 1.45 (95% CI 0.99 to 2.11) | 278 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for this single study was high. The study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| BPD at 28 days | 507 per 1000 | 613 per 1000 | RR 1.21 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.48) | 294 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for these two studies was high. The larger study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. The smaller study was not blinded and it was stopped prematurely. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| Inhaled steroids compared with systemic corticosteroids for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia among all randomised | ||||||

| Patient or population: Preterm neonates with respiratory distress Settings: NICU Intervention: Inhaled steroids Comparison: Systemic steroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic steroids | Inhaled steroids | |||||

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) | The mean duration of mechanical ventilation ranged across the systemic steroid groups from 15.2 to 17.9 days | The mean duration of mechanical ventilation ranged across the inhaled steroid groups from 20 to 21 days | 3.89 days (0.24 to 7.55) | 294 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for these two studies was high. The larger study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. The smaller study was not blinded and it was stopped prematurely. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| Duration of supplemental oxygen (days) | The mean duration of supplemental oxygen ranged across control groups from 22.7 to 49.3 days | The mean duration of supplemental oxygen in the intervention groups ranged from 38.2 to 53.0 days | 11.10 days (1.97 to 20.22) | 294 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for these two studies was high. The larger study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. The smaller study was not blinded and it was stopped prematurely. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| Hyperglycaemia | 533 per 1000 | 280 per 1000 | RR 0.52, (95% CI 0.39 to 0.71) | 278 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for this single study was high. The study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 333 per 1000 | 546 per 1000 | RR 1.64, (95% CI 1.23 to 2.17) | 278 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for this single study was high. The study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| Inhaled steroids compared with systemic corticosteroids for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia among survivors | ||||||

| Patient or population: Preterm neonates with respiratory distress Settings: NICU Intervention: Inhaled steroids Comparison: Systemic steroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic steroids | Inhaled steroids | |||||

| BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age | 333 per 1000 | 446 per 1000 | RR 1.34 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.90) | 206 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for this single study was high. The study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| BPD at 28 days | 658 per 1000 | 754 per 1000 | RR 1.14 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.34) | 233 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for these two studies was high. The larger study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. The smaller study was not blinded and it was stopped prematurely. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| Ever diagnosed as asthmatic by 7 years of age | 546 per 1000 | 231 per 1000 | RR 0.42 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.94) | 48 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for this outcome was low. This outcome was reported in a subset of infants who had been enrolled in the trial in Ireland and the UK. The assessors of all the long‐term outcomes were blinded to the original treatment group allocation. Heterogeneity/Consistency: Heterogeneity was N/A as there was only one study included in the analysis. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was low because of the small sample size. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Presence of publication bias: N/A. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

Antecedentes

Descripción de la afección

A pesar de la disponibilidad de corticosteroides prenatales (Roberts 2017), el tratamiento de sustitución con surfactantes (Bahadue 2012; Soll 2002) y otros adelantos en los cuidados intensivos neonatales, las neumopatías crónicas (displasia broncopulmonar, DBP) siguen siendo una causa importante de mortalidad y morbilidad en los niños prematuros (Horbar 1993; Lee 2000; Schwartz 1994). La incidencia de DBP tiene una relación inversa con el peso al nacer y con la edad gestacional (Lee 2000; Sinkin 1990) y se ha incrementado, en parte debido a la mejoría en la supervivencia de los recién nacidos con un peso al nacer extremadamente bajo (Shaw 1993). Entre los supervivientes, la DBP resulta en una hospitalización prolongada, un aumento del riesgo de rehospitalización y resultados adversos del desarrollo neurológico.

Cada vez hay más evidencia de investigaciones celulares y bioquímicas de que la inflamación desempeña un papel importante en la patogénesis de la DBP (Groneck 1994; Gupta 2000; Kotecha 1996; Pierce 1995; Speer 1993; Watterberg 1994; Watterberg 1996; Watts 1992). En muchos recién nacidos, la reacción inflamatoria es evidente poco después del nacimiento, lo que indica que el proceso debe haberse desencadenado en el útero (Watterberg 1996). Varios factores también pueden iniciar o agravar este proceso inflamatorio después del nacimiento. Los mismos incluyen barotrauma o volutrauma producidos por la ventilación mecánica, toxicidad del oxígeno, infecciones y presencia de conducto arterioso permeable (CAP). Las intervenciones dirigidas a reducir o modular el proceso inflamatorio pueden reducir la incidencia o la gravedad de la DBP.

Descripción de la intervención

Los corticosteroides sistémicos, debido sus fuertes propiedades antiinflamatorias, son utilizados clínicamente para reducir o limitar el proceso inflamatorio asociado con el desarrollo de la DBP. El fundamento para la administración temprana de corticosteroides es que estos fármacos pueden prevenir o minimizar los cambios inflamatorios asociados a la ventilación mecánica y disminuir la necesidad posterior de corticosteroides para el tratamiento de la DBP. Varias revisiones sistemáticas sobre el uso de corticosteroides sistémicos posnatales (temprana [< 96 horas] y moderadamente temprana [7 a 14 días]) han demostrado una reducción de la DBP a los 28 días y a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual (Arias‐Camison 1999; Bhuta 1998; Doyle 2014a; Doyle 2014b; Halliday 1999; Shah 2001). Se ha observado una marcada heterogeneidad de las dosis y de la duración del tratamiento con dexametasona entre los ensayos.

Sin embargo, hay una preocupación creciente en cuanto a que los efectos beneficiosos en el sistema pulmonar puedan ser anulados por el aumento del riesgo de efectos adversos a corto y largo plazo con el tratamiento con corticosteroides (Garland 1999; Ng 1993; Soll 1999; Stark 2001; Yeh 1997; Yeh 1998). Las complicaciones graves a corto plazo con el tratamiento temprano con corticosteroides sistémicos incluyen hemorragia y perforación gastrointestinal, hiperglucemia con requerimiento de insulina e hipertensión (Garland 1999; Soll 1999; Stark 2001). Los efectos potenciales en el crecimiento del cerebro y en el desarrollo neurológico son los déficits más alarmantes. Dos estudios de seguimiento de la administración temprana de corticosteroides sistémicos han mostrado un aumento de dos a cuatro veces en las deficiencias neuromotoras de los lactantes supervivientes tratados con dexametasona en comparación con los controles a los dos años de edad corregida (Shinwell 2000; Yeh 1998). El metanálisis ha demostrado un mayor riesgo de parálisis cerebral en los lactantes tratados de forma temprana con dexametasona (Doyle 2014b).

En las declaraciones publicadas por la European Association of Perinatal Medicine (Halliday 2001b), la American Academy of Pediatrics (Watterberg 2012) y la Canadian Pediatric Society (Jefferies 2012) no se recomienda el uso habitual de dexametasona sistémica para la prevención o el tratamiento de la DBP. Fuera del contexto de los ensayos controlados aleatorizados, el uso de corticosteroides debe limitarse a circunstancias clínicas excepcionales. Esta recomendación se basó en las preocupaciones respecto de las complicaciones a corto y largo plazo, especialmente la parálisis cerebral.

En teoría, el uso de corticosteroides inhalados puede producir efectos beneficiosos en el sistema pulmonar sin concentraciones sistémicas altas concomitantes y con un menor riesgo de efectos adversos. Los resultados de un estudio multicéntrico grande sobre el uso temprano de corticosteroides inhalados concluyeron que, entre los lactantes extremadamente prematuros, la incidencia de DBP fue menor entre los que recibieron budesonida inhalada de forma temprana que entre los que recibieron placebo, pero es posible que la ventaja se haya obtenido a expensas del aumento de la mortalidad (Bassler 2015). Los resultados de este estudio se han incluido en una revisión Cochrane (Shah 2017a) y un metanálisis (Shinwell 2016). Shinwell 2016 estableció la conclusión de que: «Los niños muy prematuros parecen beneficiarse con la administración de corticosteroides inhalados con un riesgo reducido de DBP y sin efectos sobre la muerte, otras morbilidades o eventos adversos. Se esperan ansiosamente los datos sobre los resultados respiratorios, del crecimiento y del desarrollo a largo plazo». Shah 2017a resumió los resultados de su revisión Cochrane: «Hay cada vez más evidencia de los ensayos revisados de que la administración temprana de corticosteroides inhalados a los neonatos de muy bajo peso al nacer es efectiva para reducir la incidencia de muerte o neumopatía crónica a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual, ya sea entre todos los lactantes asignados al azar o entre los supervivientes. Aunque existe significación estadística, la relevancia clínica está abierta al debate ya que el límite superior del IC para el resultado de la muerte o la DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual es infinito. Los resultados del seguimiento a largo plazo del estudio Bassler 2015 podrían afectar las conclusiones de esta revisión. Es necesario realizar más estudios para identificar el cociente riesgo:beneficio de las diferentes técnicas de administración y de los regímenes de dosificación para estos fármacos. Los estudios deben considerar los efectos beneficiosos y adversos a corto y a largo plazo de los corticosteroides inhalados, con especial atención a los resultados del desarrollo neurológico». Cabe destacar que una revisión Cochrane por Onland 2017b concluyó: «A pesar de que algunos estudios informaron de un efecto modulador de los regímenes de tratamiento a favor de los regímenes de dosis alta en la incidencia de DBP y las alteraciones del desarrollo neurológico, no pueden efectuarse recomendaciones sobre el tipo óptimo, la dosificación óptima o el momento adecuado óptimo de la administración inicial de corticosteroides para la prevención de la DBP en lactantes prematuros sobre la base del nivel actual de evidencia. Se necesita de manera urgente un ECA bien diseñado y de tamaño grande para establecer el régimen óptimo de dosificación de corticosteroides sistémicos posnatales». Aparte de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión, no se conocen otras comparaciones directas del uso temprano de corticosteroides inhalados versus corticosteroides sistémicos.

De qué manera podría funcionar la intervención

Se piensa que parte de la causa de la DBP puede residir en la inflamación de los pulmones. Como parte de un ensayo aleatorizado y controlado con placebo del tratamiento temprano con beclometasona inhalada, Gupta 2000 midió las concentraciones de interleucina‐8 (IL‐8) y del antagonista del receptor de interleucina‐1 (IL‐1ra) en los aspirados traqueales como marcadores de la inflamación pulmonar. Los lactantes tratados con beclometasona con niveles iniciales de IL‐8 moderadamente elevados recibieron menos tratamiento posterior con glucocorticosteroides sistémicos y tuvieron una menor incidencia de DBP que los lactantes no tratados. Gupta 2000 y sus coautores concluyeron que el tratamiento temprano con beclometasona inhalada se asoció con una reducción de la inflamación pulmonar después de una semana de tratamiento. Los corticosteroides, cuando se administran por vía oral o intravenosa, reducen esta inflamación en los pulmones. Sin embargo, el uso de corticosteroides se asocia con efectos secundarios graves. Su uso se ha asociado con parálisis cerebral y con un retraso en el desarrollo. Para que el fármaco llegue directamente al pulmón se ha probado la inhalación de corticosteroides como una forma de limitar los efectos adversos.

Por qué es importante realizar esta revisión

Las revisiones Cochrane han considerado el uso de corticosteroides sistémicos o inhalados en la prevención o el tratamiento de la DBP o de la neumopatía crónica. Las mismas incluyen revisiones del uso temprano (< 8 días) de corticosteroides sistémicos posnatales para prevenir la neumopatía crónica (Doyle 2014b) así como el uso tardío (> 7 días) de corticosteroides sistémicos posnatales para la neumopatía crónica (Doyle 2014a).

Otras revisiones Cochrane consideran el uso de corticosteroides inhalados en la prevención o el tratamiento de la neumopatía crónica. Shah 2017a examinó los efectos de la administración temprana de corticosteroides inhalados para la prevención de neumopatías crónicas en neonatos prematuros de muy bajo peso al nacer sometidos a ventilación. Shah 2017a informó de un aumento en la evidencia de los ensayos que indica que la administración temprana de corticosteroides inhalados a los neonatos de muy bajo peso al nacer era efectiva para reducir la incidencia de muerte o de DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual entre todos los lactantes y supervivientes asignados al azar. Aunque hubo significación estadística, la relevancia clínica fue cuestionable debido a que el límite superior del intervalo de confianza para la muerte o la DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual era infinito. Onland 2017a revisó el uso tardío (≥ 7 días) de corticosteroides inhalados para reducir la DBP en niños prematuros y estableció la conclusión de que: «Sobre la base de los resultados de la evidencia disponible actualmente, la inhalación de corticosteroides iniciada a ≥ siete días de vida para los lactantes prematuros en alto riesgo de desarrollar neumopatía crónica no puede recomendarse en este momento».

Las revisiones Cochrane han comparado los corticosteroides sistémicos y los inhalados. Shah y colegas compararon el uso de corticosteroides inhalados versus sistémicos para la prevención de las neumopatías crónicas en neonatos prematuros de muy bajo peso al nacer sometidos a ventilación (Shah 2012; Shah 2017a) y el uso de corticosteroides inhalados versus sistémicos para el tratamiento de las neumopatías crónicas en recién nacidos prematuros de muy bajo peso al nacer sometidos a ventilación (Shah 2017b).

El uso de corticosteroides para otras indicaciones en los neonatos incluye dexametasona intravenosa para facilitar la extubación (Davis 2001), el tratamiento de la hipotensión (Ibrahim 2011) y el síndrome de aspiración de meconio (Ward 2003).

El objetivo de esta revisión fue evaluar la efectividad del tratamiento con corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con el tratamiento con corticosteroides sistémicos para los recién nacidos prematuros ventilados en la primera semana de vida con objeto de prevenir la DBP. Esta es una actualización de las revisiones publicadas en 2003 y 2012 (Shah 2003; Shah 2012).

Objetivos

El objetivo principal fue comparar la efectividad de los corticosteroides inhalados frente a los corticosteroides sistémicos iniciados en los primeros siete días de vida para prevenir la muerte o la DBP (definida como la necesidad de oxígeno suplementario a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual) en lactantes ventilados con un peso al nacer ≤ 1500 g o una edad gestacional ≤ 32 semanas.

Objetivos secundarios

Comparar la efectividad de los corticosteroides inhalados frente a los corticosteroides sistémicos en otros indicadores de la DBP, la incidencia de eventos adversos y los resultados del desarrollo neurológico a largo plazo.

Métodos

Criterios de inclusión de estudios para esta revisión

Tipos de estudios

Ensayos clínicos aleatorizados o cuasialeatorizados que compararan el tratamiento con corticosteroides inhalados versus sistémicos (sin tener en cuenta la dosis y la duración del tratamiento), iniciado en la primera semana de vida en recién nacidos prematuros de muy bajo peso al nacer sometidos a ventilación asistida.

Tipos de participantes

Lactantes prematuros con un peso al nacer ≤ 1500 g o una edad gestacional ≤ 32 semanas sometidos a ventilación asistida y una edad posnatal de menos de siete días.

Tipos de intervenciones

Corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con corticosteroides sistémicos, independientemente del tipo, la dosis y la duración del tratamiento, siempre que el mismo se iniciara antes de los siete días de edad.

Tipos de medida de resultado

Resultados primarios

1. Muerte o DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual (entre todos los asignados al azar)

Resultados secundarios

1. Otros indicadores de DBP (entre todos los asignados al azar):

-

DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual (requerimiento de oxígeno suplementario a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual);

-

muerte a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual;

-

muerte o DBP a los 28 días

-

DBP a los 28 días de edad (requerimiento de oxígeno suplementario a los 28 días de edad)

-

muerte a los 28 días de edad;

-

incapacidad para llevar a cabo la extubación dentro de los 14 días del inicio del tratamiento

-

cambios en las pruebas de la función pulmonar (distensibilidad y resistencia pulmonar);

-

requerimiento tardío de tratamiento con corticosteroides sistémicos;

2. Otros indicadores de DBP (entre los supervivientes):

-

duración de la ventilación mecánica (días);

-

duración del requerimiento de oxígeno suplementario (días);

-

duración de la estancia en el hospital (días) (post hoc)

3. Eventos adversos (entre todos los asignados al azar):

-

Hiperglucemia (definida como glucosa en sangre > 10 mmol/l) durante el período de la intervención;

-

CAP definido por la presencia de signos o síntomas clínicos o por demostración a través de ecocardiografía;

-

hemorragia gastrointestinal (definida como presencia de aspirados nasogástricos u orogástricos sanguinolentos);

-

perforación gastrointestinal (definida por la presencia de aire libre en la cavidad peritoneal en una radiografía abdominal);

-

lactantes con elastasa libre en el aspirado traqueal el día 14

-

hipertensión (definida como presión arterial diastólica y sistólica > 2 desviaciones estándar [DE] por encima de la media para la edad gestacional y posnatal del recién nacido) durante el período de la intervención (Zubrow 1995);

-

neumotórax

-

otras pérdidas de aire

-

hemorragia pulmonar

-

enterocolitis necrosante (fase II y III de Bell) (Bell 1978);

-

retinopatía del prematuro, cualquier estadio, basada en la clasificación internacional (ICROP 1984);

-

retinopatía del prematuro > estadio 3; basado en la clasificación internacional (ICROP 1984);

-

sepsis definida por la presencia de signos y síntomas clínicos de infección y un cultivo positivo de un sitio normalmente estéril (sangre, LCR u orina)

-

hemorragia intraventricular de cualquier grado (definida según Papile 1978);

-

leucomalacia periventricular (definida como quistes en el área periventricular en la ecografía o la TC);

-

miocardiopatía hipertrófica definida como el engrosamiento del tabique interventricular o de la pared ventricular izquierda en la ecocardiografía;

-

neumonía según los signos clínicos y radiológicos y un cultivo positivo de material de aspiración endotraqueal;

-

crecimiento (peso, talla/altura y perímetro cefálico) a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual;

-

cataratas (definidas por la presencia de opacidades en el cristalino);

-

hipertrofia de la lengua;

-

nefrocalcinosis (definida por la presencia de ecodensidades en la médula renal por ecografía) (Saarela 1999);

-

supresión del eje hipotalámico‐pituitario‐suprarrenal evaluado por metirapona o prueba de estimulación con ACTH.

4. Resultado del desarrollo neurológico a largo plazo (entre los supervivientes):

-

Se definieron las alteraciones del desarrollo neurológico como la presencia de parálisis cerebral o retraso mental (escalas de desarrollo del recién nacido de Bayley [BSID], Mental Developmental Index [MDI] < 70) o ceguera legal (< 20/200 de agudeza visual) o sordera (con asistencia o < 60 dB en las pruebas audiométricas) evaluada a los 18 a 24 meses.

5. Se presentaron los siguientes resultados a los siete años de edad (entre los supervivientes) (análisis post hoc basados en los datos disponibles):

-

British Ability Scales, 2ª edición (proporciona una medida global de la funcionalidad cognitiva [la puntuación de la capacidad conceptual general (GCA, por sus siglas en inglés)], con una media de estandarización de 100 y una DE de 15);

-

Escalas de actividades, sociales y de competencia escolar de la Child Behaviour Checklist para niños de cuatro a 18 años de edad;

-

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) del cual se derivan las puntuaciones generales de los problemas de comportamiento, emocionales, de conducta, de hiperactividad y con los pares;

-

Parálisis cerebral;

-

La discapacidad grave se define como una puntuación GCA < 55; la ausencia de una marcha independiente, la incapacidad de vestirse o alimentarse por sí mismo, la necesidad de tratamiento continuo con oxígeno en el hogar, la alteración del comportamiento que requiere una supervisión constante, la falta de visión útil o la falta de audición útil;

-

La discapacidad moderada se definió como un puntaje de GCA de 55 a 69; movilidad restringida, ingreso en una UCI y ventilación en el último año, derivación secundaria para obtener ayuda especializada con el comportamiento, capacidad de ver solo movimientos bruscos o pérdida de audición no corregida con ayuda;

-

Muerte o discapacidad moderada/grave;

-

Presión arterial sistólica > 95 percentil;

-

Presión arterial diastólica > 95 percentil; y

-

Alguna vez fue diagnosticado como asmático a los siete años de edad.

Métodos de búsqueda para la identificación de los estudios

Búsquedas electrónicas

See Appendix 1 for the previous search methodologies.

For the 2017 update, we used the criteria and standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal (see the Cochrane Neonatal search strategy for specialized register).

We conducted a comprehensive search including: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2017, Issue 1) in The Cochrane Library; MEDLINE via PubMed (1 January 2011 to 23 February, 2017); Embase (1 January 2011 to 23 February, 2017); and CINAHL (1 January 2011 to 23 February, 2017) using the following search terms: (bronchopulmonary dysplasia OR lung diseases OR chronic lung disease OR BPD OR BPD) AND ((anti‐inflammatory agents OR steroid* OR dexamethasone OR budesonide OR beclomethasone dipropionate OR flunisolide OR fluticasone propionate OR corticosteroid* OR betamethasone OR hydrocortisone) AND (inhalation OR aerosol OR inhale*)), plus database‐specific limiters for RCTs and neonates (see Appendix 2 for the full search strategies for each database). We did not apply language restrictions.

We searched clinical trials registries for ongoing or recently completed trials (clinicaltrials.gov; the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform www.whoint/ictrp/search/en/, and the ISRCTN Registry).

Búsqueda de otros recursos

We searched the abstracts of the Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Conference electronically at Abstracts 2 view from 2010 to 2016.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

We used the methods of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group for data collection and analysis.

Selección de los estudios

We included all randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials that fulfilled the selection criteria described in the previous section. The review authors independently reviewed the results of the updated search and selected studies for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement by discussion.

Extracción y manejo de los datos

For each trial, information was sought regarding the method of randomisation, blinding and reporting of all outcomes for all the infants enrolled in the trial. Data from primary investigator were obtained for unpublished trials or when published data were incomplete. Retrieved articles were assessed and data abstracted independently by four review authors (SS, AO, HH, VS). Dr Henry Halliday did not assess the risk of bias for his trial (Halliday 2001a).

For each study, final data were entered into RevMan by one review author and then checked for accuracy by a second review author. We resolved discrepancies through discussion.

We attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details when information regarding any of the above was unclear.

Evaluación del riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos

Three review authors (SS, AO, VS) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool (Higgins 2011) for the following domains:

-

Sequence generation (selection bias).

-

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

-

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

-

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

-

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

-

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

-

Any other bias.

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third assessor (VS). See Appendix 3 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Medidas del efecto del tratamiento

We performed statistical analyses using Review Manager software (Review Manager 2014). Dichotomous data were analysed using relative risk (RR), risk difference (RD) and the number needed to benefit (NNTB) or number needed to harm (NNTH). The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported on all estimates. If more than one trial was included in an analysis we report on typical RR and typical RD.

We analysed continuous data using weighted mean difference (WMD) (if more than one trial was included in an analysis), or the standardized mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome but use different methods.

Cuestiones relativas a la unidad de análisis

For clinical outcomes such as episodes of sepsis, we analysed the data as proportion of neonates having one or more episodes.

Manejo de los datos faltantes

For included studies, levels of attrition were noted. The impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect was explored by using sensitivity analysis.

All outcomes analyses were on an intention to treat basis i.e. we included all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Evaluación de la heterogeneidad

We examined heterogeneity between trials by inspecting the forest plots and quantifying the impact of heterogeneity using the I² statistic. If noted, we planned to explore the possible causes of statistical heterogeneity using pre‐specified subgroup analysis (for example, differences in study quality, participants, intervention regimens, or outcome assessments). We used the following criteria for describing the percentages of heterogeneity: < 25% no heterogeneity, > 25% to 49% low heterogeneity, ≥ 50% to 74% moderate heterogeneity and ≥ 75% high heterogeneity.

Evaluación de los sesgos de notificación

We planned to assess possible publication bias and other biases using symmetry/asymmetry of funnel plots.

For included trials that were performed recently (and prospectively registered), we planned to explore possible selective reporting of study outcomes by comparing the primary and secondary outcomes in the reports with the primary and secondary outcomes proposed at trial registration, using the web sites www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.controlled‐trials.com. If such discrepancies were found, we planned to contact the primary investigators to obtain missing outcome data on outcomes pre‐specified at trial registration.

Síntesis de los datos

Where meta‐analysis was judged to be appropriate, the analysis was done using Review Manager software (Review Manager 2014). We used the Mantel‐Haenszel method for estimates of typical relative risk and risk difference. No continuous outcomes were included in this review. We planned to analyses continuous measures using the inverse variance method, if included. We used the fixed‐effect model for all meta‐analyses.

Quality of evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the quality of evidence. The following (clinically relevant) outcomes were assessed among all randomised infants using GRADE: primary outcome ‐ death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age among all randomised. Secondary outcomes: death or BPD at 28 days; BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age; BPD at 28 days; duration of mechanical ventilation; duration of supplemental oxygen; hyperglycaemia; and patent ductus arteriosus. The following secondary outcomes were assessed among survivors; BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age; BPD at 28 days and ever diagnosed as asthmatic at seven years of age.

Three authors (SS, AO, VS) independently assessed the quality of the evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from randomised controlled trials as high quality but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of the evidence, precision of estimates and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create a ‘Summary of findings’ table to report the quality of the evidence.

The GRADE approach results in an assessment of the quality of a body of evidence in one of four grades:

-

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

-

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

-

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

-

Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Análisis de subgrupos e investigación de la heterogeneidad

Groups were analysed based on all randomised and survivors only. We reported results of the I² test if more than one study was included in an analysis.

Análisis de sensibilidad

We planned sensitivity analyses for situations where this might affect the interpretation of significant results (e.g. where there is risk of bias associated with the quality of some of the included trials or missing outcome data). None were thought necessary in this review.

Results

Description of studies

Both studies received grant support and the industry provided aero chambers and metered dose inhalers of budesonide and placebo for the larger study. No conflict of interest was identified.

Results of the search

Five trials comparing inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids for prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) were identified, of which three were excluded. No new trials were identified for the 2011 update. For this update in 2017, 395 articles were identified through the search after duplicates were removed. One potential study was identified (Mazulov 2013), but after contact with the first author it was excluded because it was not a randomised controlled trial. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Study flow diagram: review update

Included studies

We included two trials: Groneck 1999 and Halliday 2001a (both studies published as full text articles; see Characteristics of included studies). Although both studies aimed to include infants thought to be at risk of developing BPD, the inclusion criteria, the intervention type (dose and type of inhaled steroid) and duration of therapy varied between the two studies.

Groneck 1999 was a open comparative trial which enrolled preterm infants < 1200 g while they were mechanically ventilated and had fractional inspired oxygen (FiO₂) requirement > 0.3 on the third day of life. Sixteen infants were enrolled into the study and were alternatively allocated to treatment with inhaled beclomethasone or systemic dexamethasone. Due to poor clinical results (BPD in 6/7 infants), alternate allocation to inhaled steroids was stopped for ethical reasons after inhaled steroid treatment of seven infants. Thus, seven infants were treated with inhaled steroids and nine received systemic steroids. Inhaled beclomethasone was given from day three to day 28 of life administered by an aero chamber into the ventilatory circuit at a dose of 3 x 2 puffs of 250 µg (= 1.5 mg/day). After extubation, inhalation therapy was continued by face mask, and the aero chamber was connected to a ventilation bag. No systemic steroids were given to infants treated with inhaled steroids during the first month of life. Systemic dexamethasone was given at a starting dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day for three days, starting between days 11 to 13; thereafter the dose was gradually tapered over 10 to 28 days, according to clinical status of the infant. Duration of systemic steroids was at the discretion of attending physician. Primary outcome was assessment of lung inflammation and lung permeability. Other outcome measures were days on mechanical ventilation, days on supplemental oxygen and BPD (oxygen dependency and radiological abnormalities on day 28). Pulmonary inflammation and lung permeability were assessed by analysing inflammatory mediators (interleukin ‐8, elastase alpha ‐1 proteinase inhibitor, free elastase, secretory component for IgA and albumin) in tracheal aspirates on day 10 (before starting dexamethasone) and day 14 (three days after starting dexamethasone). The baseline characteristics were similar between groups.

Halliday 2001a enrolled infants born at < 30 weeks' gestation, postnatal age < 72 hours and needing mechanical ventilation and FiO₂ > 0.30. Infants of 30 and 31 weeks could be included if they needed FiO₂ > 0.50. Infants with lethal congenital anomalies, severe intraventricular haemorrhage (grade 3 or 4) and proven systemic infection before entry were excluded from the trial. The trial was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of early (< 72 hours) and delayed (> 15 days) administration of systemic dexamethasone and inhaled budesonide. Infants were randomly allocated to one of four treatment policies in a factorial design: early (< 72 hours) dexamethasone, early budesonide, delayed selective (> 15 days) dexamethasone and delayed selective budesonide. Only the groups allocated to early budesonide or early dexamethasone are included in this review. Budesonide was administered by metered dose inhaler and a spacing chamber in a dose of 400 µg/kg twice daily for 12 days. Dexamethasone was given intravenously (IV) or orally in a tapering course beginning with 0.5 mg/kg/day in two divided doses for three days reducing by half every three days for a total of 12 days of therapy. Halliday 2001a reported that 143 infants were randomised to the early budesonide group and 135 were randomised to the early dexamethasone group. Of 143 infants randomised to early budesonide, 53 received full course, 87 received partial course, and three did not receive budesonide. Of 135 infants randomised to early dexamethasone, 53 received a full course, 76 received a partial course and six infants did not receive dexamethasone. The primary outcome was death or oxygen dependency at 36 weeks. Secondary outcome measures included death or major cerebral abnormality, duration of oxygen treatment, duration of assisted ventilation, duration of hospitalisation, death or oxygen dependency at 28 days and complications of preterm birth. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. Additional data were obtained from the authors for the outcomes of duration of ventilation and duration of supplemental oxygen (expressed as mean and SD). A subset of the infants enrolled in the OSECT study (Halliday 2001a) has been followed to a median age of seven years; 127 (84%) of 152 survivors born in the United Kingdom and Ireland were followed; of these 52 infants belonged to the early dexamethasone and early budesonide groups.

Excluded studies

We excluded four trials. Dimitriou 1997 was excluded because the investigators included non‐ventilator‐dependent infants in the study and the age of commencement of treatment varied from five to 118 days of life. Kovács 1998 was excluded because the participants received systemic dexamethasone initially followed by inhaled steroids while the control group received normal saline systemically and then by nebulization. Parikh 2004 was excluded as all study participants received systemic dexamethasone for seven days and then randomised to receive either inhaled beclomethasone or placebo. Mazulov 2013 was not a randomised controlled trial. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

In Groneck 1999 infants were alternately allocated to treatment with inhaled beclomethasone or systemic dexamethasone. Alternate allocation to inhaled steroids was stopped after treatment of seven neonates due to poor clinical results. The study was stopped prematurely. The intervention was not blinded. Outcome data were presented for all 16 babies enrolled in the study. Outcome measures were not blinded.

Halliday 2001a was a multi centre RCT involving 47 centres. The intervention was not blinded in most centres. However, in 11 centres the trial was conducted double‐blind, and in these, placebo metered dose inhalers and intravenous saline were used to mask treatment allocation. Randomisation was performed by telephoning the central randomisation centre. After identifying an eligible infant, the clinician telephoned the randomisation centre to enrol the infant and determine the treatment group. Outcomes have been reported for all infants enrolled in the study. Outcome assessments were not blinded. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. Comparisons were also made for primary outcome variables between the centres observing double blind strategy and other centres. Neurodevelopmental and respiratory follow‐up results at seven years of age for children from the UK and Ireland were reported on 28 infants in the early budesonide group (80% of survivors) and on 24 infants in the early dexamethasone group (75% of survivors).

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Groneck 1999 presented no information on how the random sequence was generated and there was no blinding of randomisation (high risk of bias). In Halliday 2001a the random sequence was generated by the trial statistician, independent of the researchers (low risk of bias).

Blinding

In Groneck 1999 there was no blinding of the intervention nor of the outcome measurement (high risk of bias). In Halliday 2001a there was blinding of the intervention and the outcome measurement in 11 centres but not in another 36 centres. All assessors were blinded to the original treatment group allocations (high risk of bias). Long‐term outcomes were assessed at seven years of age and all assessors were blinded at that time to the original treatment group allocations (low risk of bias).

Incomplete outcome data

There was complete follow up in both studies (low risk of bias).

Selective reporting

The study protocols for the Groneck 1999 study was not available to us so we can not judge if there was selective reporting or not (unclear risk). According to the first author (HH) of the Halliday 2001a study there was no selective reporting (low risk of bias)

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other sources of bias in Halliday 2001a (unclear risk of bias). In Groneck 1999 alternate allocation to inhaled steroids was stopped after treatment of seven neonates due to poor clinical results. The study was stopped prematurely (high risk of bias).

Effects of interventions

See: Summary of findings for the main comparison Inhaled steroids compared with systemic corticosteroids for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia among all randomised infants; Summary of findings 2 ; Summary of findings 3

Comparison 1: Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised infants

The following (clinically relevant) outcomes among all randomised infants were assessed using GRADE: Primary outcome ‐ Incidence of death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age among all randomised. Secondary outcomes: Incidence of death or BPD at 28 days; BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age; BPD at 28 days summary of findings Table for the main comparison; duration of mechanical ventilation; duration of supplemental oxygen; hyperglycaemia; and patent ductus arteriosus summary of findings Table 2

Primary outcomes

Death or BPD by 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

There was no significant difference in death or BPD by 36 weeks' postmenstrual age in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.35; RD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.16; Analysis 1.1; Halliday 2001a, N = 278; moderate‐quality evidence). Tests for heterogeneity not applicable.

Secondary outcomes

BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

There was no significant difference in the outcome of BPD at 36 weeks' in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.11; RD 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.00 to 0.21; Analysis 1.2; Halliday 2001a, N = 278; P = 0.05; moderate‐quality evidence). Tests for heterogeneity not applicable.

Death at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

No statistically significant effect on mortality by 36 weeks' postmenstrual age was noted in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (typical RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.23; typical RD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.05; Analysis 1.3; 2 studies, N = 294). There was no heterogeneity for this outcome for RR (I² = 0%) and low for RD (I² = 36%).

Death or BPD at 28 days

There was no statistically significant difference between the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group for the combined outcome of BPD or death at 28 days (typical RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.20; typical RD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.13; Analysis 1.4; 2 studies, N = 294; low‐quality evidence). There was high heterogeneity for this outcome for RR (I² = 78%) and for RD (I² = 90%).

BPD at 28 days of age

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of BPD at 28 days in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (typical RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.48; typical RD 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.22; Analysis 1.5; 2 studies, N = 294; low‐quality evidence). There was moderate heterogeneity for RR (I² = 72 %) and high for RD (I² = 87).

Death at 28 days

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence effect of death at 28 days in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (typical RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.25; RD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.05; Analysis 1.6; 2 studies, N = 294). Test for heterogeneity not applicable for RR; there was no heterogeneity for RD (I² = 0%).

Duration mechanical ventilation (days)

The duration of mechanical ventilation was statistically significantly longer in the inhaled steroid group as compared with the systemic steroid group (typical WMD 3.89 days, 95% CI 0.24 to 7.55; Analysis 1.7; 2 studies, N = 294; moderate‐quality evidence; I² = 0.0%).

Duration of supplemental oxygen (days)

The duration of supplemental oxygen was statistically significantly higher in the inhaled steroid group as compared with the systemic steroid group (typical WMD 11 days, 95% CI 2 to 20; Analysis 1.8; 2 studies, N = 294; moderate‐quality evidence). There was low heterogeneity for this outcome (I² = 33%).

Hyperglycaemia

A statistically significant decrease in the incidence of hyperglycaemia was noted in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group in Halliday 2001a (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.71; RD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.14; Analysis 1.9; N = 278; moderate‐quality evidence). The NNTB was 4.0 (95% CI 3 to 7). Tests for heterogeneity not applicable.

Patent ductus arteriosus

There was a statistically significant increase in the rate of PDA (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.23 to 2.17; RD 0.21, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.33; Analysis 1.10; N = 278; moderate‐quality evidence) in the group receiving inhaled steroids compared with the systemic steroid group reported by Halliday 2001a. The NNTH was 5 (95% CI 3 to 10). Tests for heterogeneity not applicable.

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of gastrointestinal haemorrhage between the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group reported by Halliday 2001a (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.02) but reduced risk for RD (RD ‐0.06, 95%CI ‐0.12 to ‐0.00; Analysis 1.11; N = 278). Because the significance levels were different for RR and RD we elected not to calculate NNTB. Tests for heterogeneity were not applicable.

Gastrointestinal perforation

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of gastrointestinal perforation for the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group reported by Halliday 2001a (RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.29) but reduced risk for RD (RD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.07 to ‐0.00; Analysis 1.12; N = 278). Because the significance levels were different for RR and RD we elected not to calculate NNTB. Tests for heterogeneity not applicable.

Infants with free elastase (inflammatory mediator) in tracheal aspirate on day 14 (Outcome 1.13):

Groneck 1999 (N = 16) reported this outcome. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of infants with detectable free elastase in tracheobronchial aspirate fluid for the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (RR 8.75, 95% CI 0.52 to 145.86; RD 0.43, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.80; Analysis 1.13) with a higher number in the inhaled steroid group. Tests for heterogeneity not applicable.

There were no statistically significant differences between the inhaled and the systemic corticosteroid groups for the following outcomes in Halliday 2001a (N = 278 infants): pneumothorax (Analysis 1.14), other air leaks (Analysis 1.15), pulmonary haemorrhage (Analysis 1.16), hypertension (Analysis 1.17), necrotizing enterocolitis (Analysis 1.18), retinopathy of prematurity ‐ any stage (Analysis 1.19), retinopathy of prematurity ≥ stage 3 (Analysis 1.20) and sepsis (Analysis 1.21).

Comparison 2: Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors

The following secondary outcomes were assessed using GRADE among survivors; BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age; BPD at 28 days and ever diagnosed as asthmatic at 7 years of age (summary of findings Table 3).

Secondary outcomes

BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of BPD at 36 weeks' among survivors in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.90; RD 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.24; Analysis 2.1; Halliday 2001a; N = 206; moderate‐quality evidence). Tests for heterogeneity not applicable.

BPD at 28 days of age

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of BPD at 28 days among survivors in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (typical RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.34; typical RD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.21; Analysis 2.2; 2 trials, N = 233; low‐quality evidence). There was high heterogeneity for this outcome for RR (I² = 75%) and for RD (I² = 76%).

No relevant data for the following outcomes were available for analyses: failure to extubate within 14 days of starting treatment, change in pulmonary function tests (lung compliance and resistance), later requirement for systemic corticosteroid therapy, intraventricular haemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, measurement of pulmonary functions, pneumonia, growth, nephrocalcinosis, cataracts, hypertrophy of tongue, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and suppression of hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis.

Long‐term follow‐up of survivors at 7 years of age

A subset (127/152, 84%) of infants born in the UK and Ireland enrolled in the OSECT study (Halliday 2001a) has been followed to a median age of seven years. Of these children, 52 belonged to the early dexamethasone and early budesonide groups; 28 children belonged to the early budesonide group and 24 children to the early dexamethasone group.

There were no statistically significant differences between the early inhaled and the early systemic corticosteroid groups for the following outcomes in Halliday 2001a which reported on 52 infants: general conceptual ability (GCA) score at seven years (Analysis 2.3), Child Behaviour Checklist at seven years (Analysis 2.4), Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire at seven years (Analysis 2.5), cerebral palsy at seven years (Analysis 2.6), moderate/severe disability at seven years (Analysis 2.7), death or moderate/severe disability at seven years (Analysis 2.8), systolic blood pressure > 95th percentile at seven years (Analysis 2.9), diastolic blood pressure > 95th percentile at seven years (Analysis 2.10). Test for heterogeneity was not applicable for any of these analyses.

Ever diagnosed as asthmatic by seven years

Halliday 2001a reported on the outcome ever diagnosed as asthmatic by seven years in 48 children. There was a significantly lower risk in the inhaled steroid group compared with the systemic steroid group (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.94; RD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐0.58 to ‐0.05; NNTB 3, 95% CI 2 to 20; Analysis 2.11; moderate‐quality evidence). Tests for heterogeneity not applicable.

Discusión

Resumen de los resultados principales

Esta revisión demostró que el uso temprano de corticosteroides inhalados no se asocia con ninguna diferencia significativa en la incidencia de muerte o displasia broncopulmonar (DBP) a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual o a los 28 días de edad en comparación con el uso temprano de corticosteroides sistémicos. No se encontró evidencia de que los corticosteroides inhalados disminuyeran la incidencia de DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual o a los 28 días de edad en comparación con los corticosteroides sistémicos. El uso de corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con corticosteroides sistémicos se asoció con un aumento en la incidencia de CAP, una mayor duración de la ventilación mecánica y una mayor duración de la administración de oxígeno suplementario. El uso de corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con el uso de corticosteroides sistémicos se asoció con una disminución en la incidencia de hiperglucemia y en la incidencia de niños a los que alguna vez se les diagnosticó asma alrededor de la edad de siete años. En un subgrupo de 52 lactantes no hubo diferencias significativas en otros resultados a largo plazo a los siete años de edad.

Esta revisión no encontró evidencia de que los corticosteroides inhalados de forma temprana otorguen ventajas importantes sobre los corticosteroides sistémicos en el tratamiento de los recién nacidos prematuros sometidos a ventilación. Se necesita realizar estudios adicionales antes de que la administración temprana de corticosteroides, ya sean inhalados o sistémicos, pueda recomendarse como segura para la prevención de la DBP en los recién nacidos prematuros. Solo se ha hecho un seguimiento de una pequeña muestra de lactantes hasta los siete años de edad, sin que se hayan observado diferencias entre los grupos de corticosteroides inhalados y sistémicos.

Ambos estudios recibieron apoyo financiero y la industria farmacéutica proporcionó aerocámaras e inhaladores de dosis medidas de budesonida y placebo para el estudio más grande. No se identificó ningún conflicto de interés.

Compleción y aplicabilidad general de las pruebas

Una observación intrigante realizada por Halliday 2001a fue la disminución estadísticamente significativa de la incidencia del conducto arterioso persistente (CAP) en los lactantes tratados con corticosteroides sistémicos en comparación con los inhalados. El uso de corticosteroides prenatales ha demostrado disminuir la incidencia de CAP (Aghajafari 2001). Se ha demostrado que el tratamiento posnatal temprano con dexametasona en lactantes prematuros con síndrome de dificultad respiratoria (SDR) disminuye la incidencia del CAP (Doyle 2014b; Yeh 1997). Heyman 1990 propuso que se puede lograr la oclusión del CAP con dexametasona. Los glucocorticosteroides pueden tener efecto sobre el CAP a través de una interferencia en la síntesis de la prostaglandina o de una reducción en la sensibilidad del músculo ductal a la prostaglandina E2 (Clyman 1981; Clyman 1987).

En la revisión actual, la hiperglucemia fue menos común en el grupo de corticosteroides inhalados. Hubo una disminución en la incidencia de hemorragia gastrointestinal y de perforación gastrointestinal en el grupo de corticosteroides inhalados de significación estadística dudosa. No hubo diferencias significativas en la incidencia de otros efectos adversos entre los grupos. En general, los corticosteroides inhalados presentarían una menor posibilidad de tener efectos adversos a corto plazo que los corticosteroides sistémicos. Sin embargo, los datos de los estudios de seguimiento a largo plazo son necesarios, antes de que se considere preferible el uso de corticosteroides inhalados en lugar de los corticosteroides sistémicos. Actualmente no se puede recomendar el uso temprano de corticosteroides inhalados en comparación con los corticosteroides sistémicos para la prevención de la DBP en el niño prematuro.

Otra preocupación importante en cuanto a los estudios sobre el tratamiento con corticosteroides inhalados es la falta de certeza con respecto a la administración y la formación de depósitos del fármaco en la orofaringe y en las vías respiratorias periféricas. Numerosos factores afectan la administración del fármaco y la formación de depósitos, incluido el número de partículas en el rango respirable, la técnica de administración (uso de inhaladores de dosis medida con o sin espaciador), los nebulizadores (a chorro o ultrasónico) y la presencia o ausencia de sonda endotraqueal. En los informes anteriores se ha demostrado que la cantidad de administración de aerosoles varía del 0,4% al 14% según la técnica utilizada (Arnon 1992; Grigg 1992; O'Callaghan 1992). Algunos estudios han sugerido que el retraso en el inicio de la actividad (Dimitriou 1997) y el perfil de riesgo similar de los corticosteroides inhalados (Shah 2003) son consistentes con sus efectos secundarios a la absorción sistémica.

La identificación de una dosis efectiva de corticosteroides inhalados y de mejorías en los sistemas de administración del fármaco, que garantice una administración selectiva en el alvéolo y en las vías respiratorias más pequeñas, puede mejorar la eficacia clínica y disminuir el perfil de efectos secundarios de los corticosteroides inhalados.

Calidad de la evidencia

Según la evaluación con criterios GRADE, la calidad de la evidencia fue de moderada a baja (Resumen de resultados, tabla 1; Resumen de resultados, tabla 2; Resumen de resultados, tabla 3). La calidad de la evidencia se disminuyó en función del diseño (riesgo de sesgo), la congruencia entre los estudios (heterogeneidad) y la precisión de las estimaciones (tamaño de la muestra).

Sesgos potenciales en el proceso de revisión

Un autor de la revisión (HH) es también el autor de un estudio incluido (Halliday 2001a). El profesor Halliday no participó en la evaluación del riesgo de sesgo ni en la extracción de datos de dicho estudio, que fue realizado por los otros tres autores de la revisión.

Acuerdos y desacuerdos con otros estudios o revisiones

Las revisiones sistemáticas de los corticosteroides sistémicos posnatales administrados de forma temprana (< 7 días de edad) frente al placebo o ningún tratamiento han mostrado una disminución significativa de la incidencia de DBP y el resultado combinado de DBP y muerte a los 28 días y 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual (Doyle 2014b; Shah 2001). Se observó un aumento dudoso del riesgo de leucomalacia periventricular en los lactantes que recibieron dexametasona. En las revisiones del tratamiento sistémico posnatal con corticosteroides administrado después de los siete días de edad se observó una disminución del resultado combinado de la DBP a las 36 semanas y la mortalidad (Doyle 2014a; Shah 2001). No hubo evidencia de que disminuyera la duración de la hospitalización ni la necesidad de oxígeno suplementario (Shah 2001). La administración temprana de corticosteroides inhalados, en las dos primeras semanas de vida, a recién nacidos de muy bajo peso al nacer sometidos a ventilación, no mostró evidencia de una disminución en la incidencia de DBP (Shah 2017a). Sin embargo, hubo cada vez más evidencia de los ensayos revisados de que la administración temprana de corticosteroides inhalados a los neonatos de muy bajo peso al nacer fue efectiva para reducir la incidencia de muerte o DBP a las 36 semanas de edad posmenstrual, ya sea entre todos los lactantes asignados al azar o entre los supervivientes.

Study flow diagram: review update

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 1 Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 2 BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 3 Death at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 4 Death or BPD at 28 days.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 5 BPD at 28 days.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 6 Death at 28 days.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 7 Duration of mechanical ventilation (days).

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 8 Duration of supplemental oxygen (days).

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 9 Hyperglycaemia.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 10 Patent ductus arteriosus.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 11 Gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 12 Gastrointestinal perforation.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 13 Infants with detectable free elastase (inflammatory mediator) in tracheal aspirate fluid on day 14.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 14 Pneumothorax.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 15 Other air leaks.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 16 Pulmonary haemorrhage.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 17 Hypertension.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 18 Necrotising enterocolitis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 19 Retinopathy of prematurity ‐ any stage.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 20 Retinopathy of prematurity ≥ stage 3.

Comparison 1 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among all randomised, Outcome 21 Sepsis.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 1 BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 2 BPD at 28 days.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 3 General conceptual ability (GCA) score at 7 years.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 4 Child Behaviour Checklist at 7 years.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 5 Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire at 7 years.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 6 Cerebral palsy at 7 years.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 7 Moderate/severe disability at 7 years.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 8 Death or moderate/severe disability at 7 years.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 9 Systolic blood pressure > 95th percentile at 7 years.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 10 Diastolic blood pressure > 95th percentile at 7 years.

Comparison 2 Inhaled versus systemic steroids among survivors, Outcome 11 Ever diagnosed as asthmatic at 7 years.

| Inhaled steroids compared with systemic corticosteroids for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia among all randomised infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: Preterm neonates with respiratory distress Settings: NICU Intervention: Inhaled steroids Comparison: Systemic steroids | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Systemic steroids | Inhaled steroids | |||||

| Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age among all randomised | 526 per 1000 | 573 per 1000 | RR 1.09 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.35) | 278 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Bias: The risk of bias for this single study was high. The study was not blinded at all sites. Only 53/135 infants randomised to systemic steroids received full course while 53/145 infants randomised to inhaled steroids received full course. We downgraded the Quality of the evidence by one step. Precision: Precison for the point estimate was acceptable Presence of publication bias: N/A. |