Intervenciones para la prevención de la obesidad infantil

Resumen

Antecedentes

La prevención de la obesidad infantil es una prioridad de la salud pública internacional, debido al importante impacto de la obesidad en las enfermedades agudas y crónicas, la salud general, el desarrollo y el bienestar. La base de la evidencia internacional de las estrategias de prevención de la obesidad es muy amplia y aumenta rápidamente. Ésta es una actualización de una revisión anterior.

Objetivos

Determinar la efectividad de una serie de intervenciones que incluyen componentes dietéticos o de actividad física, o ambos, diseñadas para prevenir la obesidad en niños.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se hicieron búsquedas en CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO y en CINAHL en junio de 2015. Se volvió a realizar la búsqueda desde junio de 2015 hasta enero de 2018 y se incluyó una búsqueda en registros de ensayos.

Criterios de selección

Ensayos controlados aleatorios (ECA) de intervenciones dietéticas o de actividad física, o intervenciones dietéticas y de actividad física combinadas, para la prevención del sobrepeso o la obesidad en niños (cero a 17 años) que informaron resultados a un mínimo de 12 semanas desde el inicio del estudio.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Dos autores de la revisión, de forma independiente, extrajeron los datos, evaluaron el riesgo de sesgo y la calidad de la evidencia con los criterios GRADE. Se extrajeron datos sobre los resultados de adiposidad, las características sociodemográficas, los eventos adversos, el proceso de intervención y los costes. Se realizaron metanálisis de los datos según el Manual Cochrane para Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions) y se presentaron metanálisis separados por grupo etarios de los niños de cero a cinco años, de seis a 12 años y de 13 a 18 años de la puntuación z del IMC y del IMC.

Resultados principales

Se incluyeron 153 ECA, la mayoría realizados en EE.UU. o Europa. Trece estudios se realizaron en países de ingresos medios‐altos (PIMA: Brasil, Ecuador, Líbano, México, Tailandia, Turquía, la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México), y uno de ellos se realizó en un país de ingresos medios‐bajos (PIMB): Egipto). La mayoría (85) se centró en los niños de seis a 12 años.

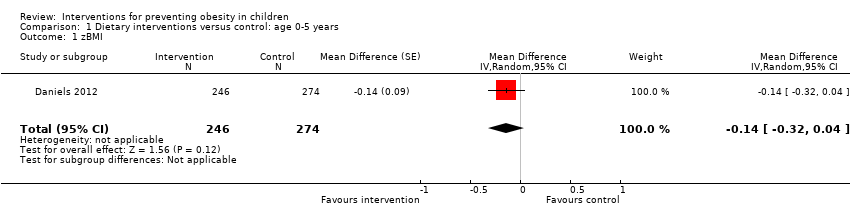

Niños entre cero y cinco años: Existe evidencia de certeza moderada de 16 ECA (n = 6261) de que la dieta combinada con intervenciones de actividad física, en comparación con el control, redujo el IMC (diferencia de medias [DM] ‐0,07 kg/m2; intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: ‐0,14 a ‐0,01) y tuvo un efecto similar (11 ECA, n = 5536) sobre la puntuación z del IMC (DM ‐0,11; IC del 95%: ‐0,21 a 0,01). Ni las intervenciones dietéticas (evidencia de certeza moderada) ni las de actividad física solas (evidencia de certeza alta) en comparación con el control redujeron el IMC (actividad física sola): DM ‐0,22 kg/m2; IC del 95%: ‐0,44 a 0,01) ni la puntuación z del IMC (dieta sola: DM ‐0,14; IC del 95%: ‐0,32 a 0,04; actividad física sola: DM 0,01; IC del 95%: ‐0,10 a 0,13) en los niños de cero a cinco años.

Niños entre seis y 12 años de edad: Existe evidencia de certeza moderada de 14 ECA (n = 16 410) de que las intervenciones de actividad física, en comparación con el control, redujeron el IMC (DM ‐0,10 kg/m2; IC del 95%: ‐0,14 a ‐0,05). Sin embargo, hay evidencia de certeza moderada de que tuvieron poco o ningún efecto sobre la puntuación z del IMC (DM ‐0,02; IC del 95%: ‐0,06 a 0,02). Existe evidencia de certeza baja de 20 ECA (n = 24 043) de que la dieta combinada con intervenciones de actividad física, en comparación con el control, redujo la puntuación z del IMC (DM ‐0,05 kg/m2; IC del 95%: ‐0,10 a ‐0,01). Existe evidencia de certeza alta de que las intervenciones dietéticas, en comparación con el control, tuvieron poca repercusión sobre la puntuación z del IMC (DM ‐0,03; IC del 95%: ‐0,06 a 0,01) o el IMC (‐0,02 kg/m2; IC del 95%: ‐0,11 a 0,06).

Niños entre 13 y 18 años de edad: Existe evidencia de certeza muy baja de que las intervenciones de actividad física, en comparación con el control, redujeron el IMC (DM ‐1,53 kg/m2; IC del 95%: ‐2,67 a ‐0,39; cuatro ECA; n = 720) y evidencia de certeza baja de una reducción en la puntuación z del IMC (DM ‐0,2; IC del 95%: ‐0,3 a ‐0,1; un ECA; n = 100). Existe evidencia de certeza baja de ocho ECA (n = 16 583) de que la dieta combinada con intervenciones de actividad física, en comparación con el control, no tuvo efectos sobre el IMC (DM ‐0,02 kg/m2; IC del 95%: ‐0,10 a 0,05) ni la puntuación z del IMC (DM 0,01; IC del 95%: ‐0,05 a 0,07; 6 ECA; n = 16 543). La evidencia obtenida a partir de dos ECA (evidencia de certeza baja; n = 294) no encontró efectos de las intervenciones dietéticas sobre el IMC.

Comparaciones directas de las intervenciones: Dos ECA proporcionaron datos que compararon directamente la dieta con la actividad física o la dieta combinada con intervenciones de actividad física en niños de seis a 12 años de edad y no informaron de diferencias.

Se observó heterogeneidad en los resultados de los tres grupos etarios, que no se pudo explicar por completo por el contexto o la duración de las intervenciones. Cuando se informaron, las intervenciones no parecieron provocar efectos adversos (16 ECA) o aumentar las desigualdades en materia de salud (género): 30 ECA; nivel socioeconómico: 18 ECA), aunque relativamente pocos estudios examinaron estos factores.

La repetición de las búsquedas en enero de 2018 identificó 315 registros con relevancia potencial para esta revisión, que se resumirán en la próxima actualización.

Conclusiones de los autores

Las intervenciones que incluyen dieta combinada con intervenciones de actividad física pueden reducir el riesgo de obesidad (puntuación z del IMC y IMC) en los niños pequeños de cero a cinco años. Existe evidencia de calidad más baja a partir de un único estudio de que las intervenciones dietéticas pueden ser beneficiosas.

Sin embargo, las intervenciones que se centran solo en la actividad física no parecen ser efectivas en los niños de esta edad. Por el contrario, las intervenciones que solo se centran en la actividad física pueden reducir el riesgo de obesidad (IMC) en los niños de seis a 12 años y en los adolescentes de 13 a 18 años. En estos grupos etarios no hay evidencia de que las intervenciones que solo se centran en la dieta sean efectivas, y hay alguna evidencia de que la dieta combinada con intervenciones de actividad física puede ser efectiva. Es importante destacar que esta revisión actualizada también indica que las intervenciones para prevenir la obesidad infantil no parecen producir efectos adversos ni desigualdades en términos de salud.

La revisión no se actualizará en su forma actual. Para controlar el aumento de los ECA de intervenciones de prevención de la obesidad infantil, en el futuro, esta revisión se dividirá en tres revisiones separadas según la edad del niño.

PICO

Resumen en términos sencillos

¿Las estrategias de dieta y actividad física ayudan a prevenir la obesidad en los niños (0 a 18 años)?

Antecedentes

A nivel mundial, cada vez más niños presentan sobrepeso y obesidad. El sobrepeso en la infancia puede causar problemas de salud y los niños pueden verse afectados psicológicamente y en su vida social. Es probable que los niños con sobrepeso también tengan sobrepeso cuando sean adultos y continúen presentando a una salud física y mental deficientes.

Búsqueda de estudios

Se realizaron búsquedas en muchas bases de datos científicas para encontrar estudios que analizaran las formas de prevenir la obesidad infantil. Se incluyeron los estudios dirigidos a niños de todas las edades. Los estudios solo se incluyeron si los métodos que utilizaron tenían como objetivo cambiar la dieta de los niños, su nivel de actividad física o ambos. Solo se buscaron los estudios que contenían la mejor información para responder a esta pregunta, los "ensayos controlados aleatorios" o ECA.

Datos encontrados

Se encontraron 153 ECA. Los estudios se realizaron principalmente en países de ingresos altos como los EE.UU. y países europeos, aunque el 12% se realizó en países de ingresos medios (Brasil, Ecuador, Egipto, Líbano, México, Tailandia y Turquía). Poco más de la mitad de los ECA (56%) probaron estrategias para cambiar la dieta o los niveles de actividad en niños de seis a 12 años, una cuarta parte fueron en niños de cero a cinco años y una quinta parte (20%) en adolescentes de 13 a 18 años. Las estrategias se utilizaron en diferentes contextos, como el domicilio, el preescolar o la escuela, y la mayoría de ellas estaban dirigidas a tratar de cambiar el comportamiento individual.

¿Estas estrategias funcionaron?

Una forma muy aceptada de evaluar si un niño tiene sobrepeso es calcular una puntuación basada en su estatura y su peso, y relacionarla con el peso y la estatura de muchos niños de su edad en su país. A esta puntuación se le denomina puntuación z del IMC. Se encontraron 61 ECA con más de 60 000 niños que informaron puntuaciones z del IMC. Los niños de cero a cinco años y los niños de seis a 12 años que recibieron ayuda con una estrategia para cambiar su dieta o sus niveles de actividad redujeron su puntuación z del IMC en 0,07 y 0,04 unidades respectivamente en comparación con los niños a los que no se les proporcionó una estrategia. Este hecho significa que estos niños pudieron reducir su peso. Este cambio en la puntuación z del IMC, cuando se proporciona a muchos niños de toda una población, es útil para que los gobiernos traten de enfrentar los problemas de obesidad infantil. Las estrategias para cambiar la dieta o la actividad física, o ambas, administradas a adolescentes y adultos jóvenes de 13 a 18 años de edad, no redujeron de forma exitosa la puntuación z del IMC.

Se intentó determinar si las estrategias podían funcionar de manera equitativa en todos los niños, por ejemplo, niñas y niños, niños de ámbitos ricos o menos ricos y niños de orígenes raciales diferentes. No hubo muchos ECA que informaran sobre lo anterior, pero en los que lo hicieron, no hubo indicios de que las estrategias aumentaran las desigualdades. Sin embargo, no fue posible encontrar suficientes ECA con esta información que permitieran responder esta pregunta. También se intentó determinar si los niños se veían perjudicados por alguna de las estrategias, por ejemplo, presentaran lesiones, perdieran demasiado peso o desarrollaran puntos de vista perjudiciales sobre sí mismos y su peso. No hubo muchos ECA que informaran sobre lo anterior, pero de los que lo hicieron, ninguno informó de daños en los niños a los que se les habían proporcionado estrategias para cambiar su dieta o su actividad física.

Se analizó qué tan bien se realizaron los ECA para ver si podían estar sesgados. Se decidió disminuir la calidad de alguna información sobre la base de estas evaluaciones. La calidad de la evidencia fue "moderada" en los niños de cero a cinco años de edad para la puntuación z del IMC, "baja" para los niños de seis a 12 años y moderada en los adolescentes (13 a 18 años).

Conclusiones

Las estrategias para cambiar la dieta o los niveles de actividad, o ambos, de los niños, con el objetivo de ayudar a prevenir el sobrepeso o la obesidad, son efectivas para realizar reducciones modestas en la puntuación z del IMC en los niños de cero a cinco años y en los niños de seis a 12 años. Esta información puede ser útil para los padres y los niños preocupados por el sobrepeso. También puede ser útil para los gobiernos, que intentan hacer frente a una tendencia creciente de niños que presentan obesidad o sobrepeso. Se encontró menos evidencia de los adolescentes y los jóvenes de 13 a 18 años, y las estrategias que se les proporcionaron no redujeron la puntuación z del IMC.

Conclusiones de los autores

Summary of findings

| Dietary interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 0‐5 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with dietary interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.75 | MD 0.14 lower (0.32 lower to 0.04 higher) | 520 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Dietary interventions likely result in little to no difference in zBMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| 1Risk of bias: there is only one study and it has one domain (incomplete outcome data) rated as high risk of bias, with 22% of participants dropping out of the study. | |||||

| Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 0‐5 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 15.94 to 16.4 kg/m2 | MD 0.22 kg/m2 lower | 2233 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Physical activity interventions likely do not reduce BMI |

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from −0.15 to −0.22 | MD 0.01 higher | 1053 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Physical activity interventions likely do not reduce zBMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children age 0‐5 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 0‐5 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with diet and physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.15 to 0.98 | MD 0.07 lower (0.14 lower to 0.01 lower) | 6261 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Diet and physical activity interventions potentially slightly reduce zBMI |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 15.8 to 17.62 kg/m2 | MD −0.11 kg/m2 lower | 5536 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Diet and physical activity interventions likely result in little to no difference in BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| 1Heterogeneity of this analysis as measured with I2 statistic was 66%, and therefore at high risk of bias. | |||||

| Adverse event outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 0 to 5 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 0 to 5 years | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence |

| Insufficient weight gain in infants | One study of an infant feeding intervention. There was no difference in numbers of infants with weight < 5th percentile between intervention and control groups nor in the numbers of children dropping by 2 major centiles between year 1 and year 2, but this was just 80 participants. | 110 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

| Physical injuries | No effect of intervention on numbers of physical injuries reported in the control and intervention arms | 652 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Adverse events | No 'adverse events' reported | 983 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Infections | No effect of intervention on numbers of reported infections. These data are very uncertain. A single study of just 41 participants found similar numbers of (parent‐reported) infections in children in the intervention and control groups. | 709 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Accidents | No effect on number of accidents. These data are very uncertain. A single study of just 41 participants found similar numbers of (parent‐reported) accidents in children in the intervention and control groups. | 42 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

| RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||

| 1Downgraded three times. Twice for imprecision, as evidence based on just one study with only 110 participants. Downloaded once for risk of bias as we judged three domains at high risk of bias and two unclear from a total of six items. | |||

| Dietary interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with dietary interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.09 to 0.41 | MD 0.03 lower (0.06 lower to 0.01 higher) | 7231 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Dietary interventions alone do not reduce zBMI |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 17.9 to 25.1 kg/m2 | MD 0.02 kg/m2 lower (0.11 lower to 0.06 higher) | 5061 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Dietary interventions alone do not reduce BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.09 to 1.75 | MD 0.02 lower (0.06 lower to 0.02 higher) | 6841 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Physical activity interventions likely result in little to no difference in zBMI. Physical activity vs control ‐ setting |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 15.7 to 20.41 kg/m2 | MD 0.1 kg/m2 lower | 16,410 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Physical activity interventions likely reduce BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| 1Four of seven studies have at least one domain judged to be high risk of bias. In addition removal of these studies substantially changes the effect of having an intervention, from no effect to there being a positive effect of the intervention. | |||||

| Adverse event outcomes for physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence |

| Physical injuries | No effect on numbers of children with physical injuries in the control and intervention arms | 912 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Underweight | No effect on number (proportion) of children designated as underweight | 5266 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ |

| Depression | Depression was reduced in children in the intervention group (MD −0.21, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.001) | 225 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Body satisfaction | No effect of intervention on reported body satisfaction at the end of the intervention | 225 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Increased weight concerns | No effect of intervention on reported body satisfaction at the end of the intervention | 225 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||

| 1Downgraded for risk of bias because this study has one domain at high risk of bias. Downgraded for imprecision because only one of 22 studies reported this outcome. | |||

| Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with diet and physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.05 to 0.9 | MD 0.05 lower (0.10 lower to 0.01 lower) | 24,043 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Diet and physical activity interventions combined may reduce zBMI slightly |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 17.57 to 24.8 kg/m2 | MD 0.05 kg/m2 lower (0.11 lower to 0.01 higher) | 19,498 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Diet and physical activity interventions combined may result in little to no difference in BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| 1Heterogeneity was very high with an I2 statistic of 87%. | |||||

| Adverse event outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 6 to 12 years | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence |

| Underweight | No effect on number (proportion) of children designated as underweight | 784 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

| Depression | Depression was reduced in children in the intervention group (MD −0.21, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.001) Baseline depression score of the control group was 2.09 (SD 2.74) | 225 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Increased weight concern | No effect of the intervention on concern about weight | 285 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ |

| Body satisfaction | No effect of intervention (diet and physical activity) on reported body satisfaction at the end of the intervention | 1128 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ |

| Visits to a healthcare provider | Visits to a healthcare provider were similar in the intervention and control groups; N = 1 in intervention and N = 2 in control | 60 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Adverse events related to taking of blood samples | < 3%, similar numbers in the intervention (1.6%) and control (1.7%) groups (RD 0.00, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.01) | 4603 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

| Underweight | Waist circumference of children < 10th centile for weight did not differ between the intervention and control group (P = 0.373) | 724 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

| Injuries | Similar numbers of children were reported with injuries in the intervention (11%, N = 2) and control (4.7%, N = 1) groups | 60 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||

| 1Downgraded for risk of bias because one of the studies had an outcome rated as high risk of bias. | |||

| Diet interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with diet interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI was 24.8 kg/m2 | MD 0.13 kg/m2 lower (0.50 lower to 0.23 higher) | 294 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Diet interventions may result in little to no difference in BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| 1There are two studies and one has two domains at high risk of bias. | |||||

| Physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with physical activity interventions | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.21 to 0.81 | MD 0.2 lower (0.3 lower to 0.1 lower) | 100 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The evidence suggests physical activity interventions reduce zBMI |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI was 20.4 to 26.65 kg/m2 | MD 1.53 kg/m2 lower | 720 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of physical activity interventions on BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| 1One study with only 100 participants. | |||||

| Adverse event outcomes for physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children age 13 to 18 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence |

| Body satisfaction | No effect of intervention on reported body satisfaction at the end of the intervention | 190 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Unhealthy weight gain | No effect of intervention on unhealthy gains in weight | 546 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

| Self‐acceptance/self‐worth | One study (N = 190) reported no effect of intervention on self‐acceptance. A second CRt of the same intervention reported improved self‐worth in those children who received the intervention | 546 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

| Binge eating | No effect of intervention on binge eating | 556 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ |

| RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||

| 1Downgraded as this study has two domains at high risk of bias. | |||

| Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged 13 to 18 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with diet and physical activity interventions combined | ||||

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI ranged from 0.21 to 0.81 | MD 0.01 higher (0.05 lower to 0.07 higher) | 16,543 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Combined diet and physical activity interventions may result in little to no difference in zBMI |

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 18.99 to 24.57 kg/m2 | MD 0.02 kg/m2 lower (0.1 lower to 0.05 higher) | 16,583 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Combined diet and physical activity interventions may result in little to no difference in BMI |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| 1Heterogeneity is very high, measured at 92% with I2 statistic. | |||||

| Adverse events outcomes for dietary combined with physical activity interventions compared to control for preventing obesity in children aged13 to 18 years | |||

| Patient or population: children aged 13‐18 years | |||

| Outcomes | Impact | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence |

| Depression | No effects of the intervention on depression | 779 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ |

| Clinical levels of shape and weight concern | No effect of intervention on clinical numbers of shape or weight concern | 282 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

| Anxiety | No effect of the intervention on anxiety | 779 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ |

| RCT: randomised controlled trial | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||

| 1Downgraded for risk of bias because these data appear to be from a post hoc subgroup analysis. | |||

| Dietary interventions compared to physical activity interventions for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with physical activity interventions | Risk with dietary intervention | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI ranged from 17.4 to 18.8 kg/m2 | MD 0.03 kg/m2 lower (0.25 lower to 0.2 higher) | 4917 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Dietary interventions result in little to no difference in BMI compared to physical activity interventions when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.2 | MD 0.11 lower | 1205 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | 'Dietary interventions' results in little to no difference in zBMI compared to physical activity interventions when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| Diet and physical activity interventions combined compared to physical activity interventions alone for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with physical activity interventions | Risk with diet and physical activity interventions combined | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI was 17.7 kg/m2 | MD 0.04 kg/m2 lower (1.05 lower to 0.97 higher) | 3946 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Combined dietary and physical activity interventions result in little to no difference in BMI compared to physical activity interventions when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.15 | MD 0.16 lower (0.57 lower to 0.25 higher) | 3946 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Combined dietary and physical activity intrventions result in little to no difference in zBMI compared to physical activity interventions when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| Dietary interventions alone compared to diet and physical activity interventions combined for preventing obesity in children aged 6 to 12 years | |||||

| Patient or population: children aged 6‐12 years | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with diet and physical activity interventions combined | Risk with dietary intervention | ||||

| Body‐mass index (BMI) | The mean BMI was 17.4 kg/m2 | MD 0.28 kg/m2 lower (1.67 lower to 1.11 higher) | 3971 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Dietary interventions alone result in little to no difference in BMI compared to diet and physical activity interventions combined when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| Body‐mass index z score (zBMI) | The mean zBMI was 0.2 | MD 0.05 higher (0.38 lower to 0.48 higher) | 3971 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Dietary interventions alone result in little to no difference in zBMI compared to diet and physical activity interventions combined when delivered in schools to children aged 6‐12 years |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

Antecedentes

La prevención de la obesidad es una prioridad de salud pública internacional (WHO 2016), y cada vez hay más evidencia del impacto del sobrepeso y la obesidad en el funcionamiento, la salud y el bienestar a corto y largo plazo (Reilly 2011). En una amplia variedad de países (incluidos, más recientemente, los países de ingresos medios y bajos), se han registrado tasas elevadas y crecientes de sobrepeso y obesidad en los últimos 30 a 40 años (WHO 2016).

La evidencia global indica que la prevalencia del sobrepeso y la obesidad en los niños comenzó a aumentar a finales de los años ochenta, GBD Obesity Collaboration 2014. En 2010, 43 000 000 de niños menores de cinco años presentaban sobrepeso u obesidad, y aproximadamente 35 000 000 de estos niños vivían en países de ingresos bajos y medios (de Onis 2010). A nivel internacional, las tasas de obesidad infantil siguen aumentando en algunos países (p.ej., México, India, China, Canadá), aunque hay evidencia de una desaceleración de este aumento o de un estancamiento en algunos grupos de edad en algunos países (WHO 2016). La Comisión de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) para la Erradicación de la Obesidad Infantil (WHO 2016) determinó que la obesidad infantil, incluida la obesidad en niños y adolescentes en edad preescolar, alcanza proporciones alarmantes en muchos países y plantea un desafío urgente e importante. En los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible, establecidos por las Naciones Unidas en 2015, también se considera que la prevención y el control de las enfermedades no transmisibles, incluida la obesidad, son prioridades fundamentales (Naciones Unidas).

Una vez establecida la obesidad infantil, es difícil revertirla a través de intervenciones (Al‐Khudairy 2017; Mead 2017), y se prolonga hasta la edad adulta (Singh 2008; Whitaker 1997), lo que refuerza el argumento a favor de la prevención primaria. La obesidad en los adultos se asocia con un mayor riesgo de enfermedad cardíaca, accidente cerebrovascular, síndrome metabólico, diabetes tipo 2 y algunos tipos de cáncer (Bhaskaran 2014; Yatsuya 2010). Los niños con obesidad tienen un bienestar psicológico más deficiente y niveles elevados de una serie de factores de riesgo cardiometabólicos (Kipping 2008a). Las comorbilidades de la obesidad como la hipertensión arterial, el colesterol alto en sangre y la insensibilidad a la insulina, se observan a una edad cada vez más temprana. La obesidad infantil puede causar problemas musculoesqueléticos, apnea obstructiva del sueño, asma y una serie de problemas psicológicos (NHS England 2014). La obesidad infantil se asocia con la diabetes tipo 2 y las enfermedades cardíacas en la edad adulta y con mortalidad a mediana edad (Public Health England 2015). Tratar la obesidad es muy caro; en el Reino Unido se calculó (en 2014) que el NHS gastó 5 100 000 000 de libras esterlinas al año en enfermedades relacionadas con la obesidad (Dobbs 2014).

Es probable que los esfuerzos primarios de prevención tengan efectos óptimos si se inician en la primera infancia con la participación de los padres (Summerbell 2012). Desde el nacimiento hasta el comienzo de la escuela primaria es un momento crucial para las intervenciones de prevención de la obesidad, cuando se establece entre padres e hijos la dieta y la conducta relacionada con la actividad. Las intervenciones de modificación del estilo de vida para mejorar la calidad de la dieta, aumentar los niveles de actividad física y reducir las conductas sedentarias, a menudo mediante el uso de técnicas de cambio de conducta y la participación de los padres o cuidadores, o ambos, son el pilar de las intervenciones en niños en edad preescolar. Al intervenir a una edad tan temprana, puede ser posible prevenir que los niveles de obesidad sigan aumentando en las generaciones futuras y es fundamental para reducir las desigualdades en salud (Marmot 2010). Como destaca la Comisión (WHO 2016), la adolescencia puede ser un momento crítico para el aumento de peso excesivo, ya que este grupo de edad normalmente tiene más libertad en la elección de alimentos y bebidas fuera del hogar en comparación con los niños más pequeños. Lo anterior, junto con el hecho de que la actividad física suele disminuir durante la adolescencia, especialmente en las niñas, ofrece tanto oportunidades como barreras para quienes desarrollan intervenciones.

La prevalencia de la obesidad también está fuertemente vinculada al grado de desigualdad social relativa, con una mayor desigualdad social asociada a un mayor riesgo de obesidad en la mayoría de los países de ingresos altos (incluso en lactantes y niños pequeños [Ballon 2018]), pero en la mayoría de los países de ingresos bajos y medios se observa una relación inversa (Monteiro 2004). Por lo tanto, es fundamental que para prevenir la obesidad también se reduzca la brecha asociada en las desigualdades en salud, y garantizar que las intervenciones no tengan resultados más favorables en las personas con una posición socioeconómicamente más ventajosa en la sociedad. La base de conocimientos disponible sobre la que desarrollar una plataforma de acción para la prevención de la obesidad y basar las decisiones en las intervenciones de salud pública adecuadas para reducir el riesgo de obesidad en toda la población, o dirigidas a los grupos de mayor riesgo, todavía es limitada (Gortmaker 2011; Hillier‐Brown 2014).

La Comisión de la OMS (WHO 2016) señala que los avances en la lucha contra la obesidad infantil han sido lentos e inconsistentes, y que la prevención y el tratamiento de la obesidad requieren un enfoque de todo el gobierno en el que las políticas de todos los sectores tengan en cuenta de forma sistemática la salud, eviten los efectos perjudiciales para la salud y mejoren así la salud de la población y la equidad sanitaria. De hecho, en la actualidad se reconoce que la lucha contra la obesidad requiere un enfoque sistémico e iniciativas políticas en todos los departamentos del gobierno de manera conjunta (Rutter 2017). Sin embargo, como Knai y colegas han señalado en relación con el Capítulo 2 del Childhood Obesity Plan de Inglaterra, este país aún depende de la autorregulación a nivel individual (Knai 2018). La Comisión de la OMS (WHO 2016) indica que las intervenciones preliminares que proporcionan orientación y formación a los cuidadores que trabajan en centros e instituciones de cuidado infantil sobre el asesoramiento adecuado en materia de alimentación, actividad física y sueño de los niños en edad preescolar pueden ser particularmente importantes. La Comisión de la OMS (WHO 2016) también indica que las intervenciones preliminares pueden ser particularmente importantes para los adolescentes, por ejemplo, las dirigidas a la comercialización de alimentos poco saludables como las bebidas azucaradas; las que enfrentan el entorno obesogénico, como los puntos de venta de alimentos para llevar.

El objetivo de esta revisión fue actualizar la base de evidencia en los niños debido al crecimiento exponencial de los estudios en este campo en los últimos cinco a diez años, y así asegurar que la revisión se mantenga actualizada y sea relevante para la política y la práctica, con especial atención en la equidad en salud. Esta revisión Cochrane se actualizó para incluir los datos informados en los ensayos controlados aleatorios (ECA) publicados hasta 2015 inclusive. En esta actualización se presentan los datos por grupos de edad, de cero a cinco años, de seis a 12 años y de 13 a 18 años. También se proporciona una lista de ECA publicados entre 2016 y 2018 que se consideró, a partir de la información presentada en el resumen, que es probable que cumplan con los criterios de inclusión de esta revisión.

En el futuro la revisión se dividirá en tres revisiones según la edad del niño: de cero a cinco años; de seis a 12 años y de 13 a 18 años. Es razonable pensar que diferentes intervenciones podrían funcionar de manera diferente en niños de diferentes edades. Por ejemplo, la participación significativa de los padres puede ser un factor clave para la eficacia de las intervenciones en los niños en edad preescolar, pero éste puede no ser el caso en los adolescentes; los adolescentes pueden encontrar las intervenciones en línea fáciles de utilizar, así como atractivas e interesantes, debido a su capacidad cognitiva y afinidad por los medios sociales, pero estos tipos de intervenciones pueden no funcionar bien en los niños más pequeños.

Descripción de la afección

Sobrepeso y obesidad son términos utilizados para describir un exceso de adiposidad (o grasa) por encima del ideal para una buena salud. La opinión actual de los expertos apoya el uso de los puntos de corte del índice de masa corporal (IMC) para determinar el estado del peso (como peso saludable, sobrepeso u obesidad) de niños y adolescentes, y se han desarrollado varios puntos de corte estándar del IMC (Cole 2000; Cole 2007; de Onis 2004; de Onis 2007). A pesar de lo anterior, no existe una aplicación consistente de esta metodología por parte de los expertos y también se utilizan diversos métodos basados en percentiles, lo que puede dificultar la comparación de los ECA que han utilizado diferentes medidas y resultados de peso.

Se sabe que el sobrepeso y la obesidad en la infancia tienen un impacto significativo en la salud física y psicosocial (revisado en Lobstein 2004). De hecho, muchas de las consecuencias cardiovasculares que caracterizan la obesidad en la edad adulta van precedidas de anomalías que comienzan en la infancia. La hiperlipidemia, la hipertensión, la tolerancia anormal a la glucosa (Freedman 1999) y la diabetes tipo 2 (Arslanian 2002), ocurren con mayor frecuencia en niños y adolescentes obesos. Además, se sabe que la obesidad en la infancia y la adolescencia son factores de riesgo independientes de la obesidad en los adultos (Must 1992; Must 1999; Power 1997; Singh 2008; Whitaker 1997), lo que subraya la importancia de los esfuerzos de prevención de la obesidad.

Determinantes modificables de la obesidad infantil

La obesidad es el resultado de un desequilibrio energético positivo y sostenido, y en su desarrollo se han visto implicados una variedad de factores genéticos, conductuales, culturales, ambientales y económicos (analizado en Lobstein 2004). La interacción de estos factores es compleja y ha sido objeto de considerables investigaciones; sin embargo, la carga de la obesidad no se experimenta de manera uniforme en toda la población, y los niveles más altos de la afección los presentan las personas más desfavorecidas. En los países de ingresos altos se observa una tendencia significativa entre la obesidad y el bajo nivel socioeconómico, mientras que en algunos países en desarrollo se observa lo contrario, con niños de familias relativamente acomodadas más vulnerables a la obesidad.

Descripción de la intervención

Esta revisión incluye la evaluación de intervenciones educativas, conductuales y de promoción de la salud. Los términos "intervención" y "programa" se utilizan de manera indistinta a lo largo de esta revisión. La Ottawa Charter define cuatro áreas de acción para la promoción de la salud: 1) acciones para desarrollar las capacidades personales, que son acciones dirigidas a las capacidades, conductas, conocimientos y creencias individuales; 2) acciones para reforzar las acciones comunitarias, que son acciones dirigidas a las comunidades e incluyen enfoques medioambientales y basados en el entorno para la promoción de la salud; 3) acciones para reorientar los servicios de salud, que son acciones dentro del sector de la salud y se relacionan con la prestación de servicios; y 4) acciones para construir políticas públicas sanas y crear entornos de apoyo, que son intersectoriales en su naturaleza y se relacionan con la creación de entornos físicos, sociales y de políticas que promuevan la salud, WHO 1986.

Por qué es importante realizar esta revisión

Se insta a los gobiernos de todo el mundo a que tomen medidas para prevenir la obesidad infantil y abordar los determinantes subyacentes de la enfermedad. Para proporcionar a los responsables de la toma de decisiones evidencia de investigación de alta calidad que informe la planificación y la asignación de los recursos, esta revisión tiene como objetivo proporcionar una actualización de la evidencia de los ECA diseñados para comparar el efecto de las intervenciones para prevenir la obesidad infantil con el efecto de recibir una intervención alternativa o ninguna intervención. Se intentó actualizar la revisión anterior (Waters 2011), que concluyó que muchas intervenciones dietéticas y de ejercicios para prevenir la obesidad en niños parecían ineficaces para prevenir el aumento de peso, pero podían ser efectivas para promover una dieta saludable y mayores niveles de actividad física. La revisión anterior también instó a reconsiderar la conveniencia de la duración de los estudios, los diseños y la intensidad de la intervención, además de hacer recomendaciones con respecto al informe completo de los ECA. Sin embargo, en general, aunque no hubo evidencia suficiente para determinar que un programa en particular pudiera prevenir la obesidad infantil, la evidencia indicó que las estrategias integrales para aumentar el consumo de una dieta saludable por parte de los niños y sus niveles de actividad física, junto con el apoyo psicosocial y el cambio ambiental, eran las más prometedoras. Se incorporó la evidencia de investigación que se ha publicado desde entonces y que también es consistente con temas emergentes relacionados con la revisión y la síntesis de la evidencia (Higgins 2011a). También se observó el importante trabajo en torno a la aplicación de políticas e intervenciones para prevenir la obesidad infantil (Wolfenden 2016a). Además, para satisfacer la creciente demanda de los profesionales de la salud pública y de la promoción de la salud, así como de los responsables de la toma de decisiones, se ha intentado incluir información relacionada no solo con el impacto de las intervenciones en la prevención de la obesidad, sino también con la forma en que se lograron los resultados, la forma en que se realizaron las intervenciones, el contexto en el que se llevaron a cabo (Wang 2006) y la medida en que funcionaron de manera equitativa (Tugwell 2010). Este nuevo aspecto de la revisión se guió en parte por las Revisiones Sistemáticas de Promoción de la Salud y las Intervenciones de Salud Pública (Armstrong 2007), más las recomendaciones de revisiones complejas y la evidencia útil para los responsables de la toma de decisiones (Waters 2011), y la información se completó con la opinión de expertos.

Objetivos

El objetivo principal de la revisión fue determinar la efectividad de una serie de intervenciones que incluyen componentes de la dieta o la actividad física, o ambos, diseñados para prevenir la obesidad infantil, mediante la actualización de la versión 2011 de la revisión (Waters 2011). Los objetivos específicos incluyen:

-

evaluación del efecto de las intervenciones educativas dietéticas versus control sobre los cambios en la puntuación z del IMC, el IMC y los eventos adversos en niños menores de 18 años;

-

evaluación del efecto de las intervenciones de actividad física versus control sobre los cambios en la puntuación z del IMC, el IMC y los eventos adversos en niños menores de 18 años;

-

evaluación de los efectos combinados de las intervenciones educativas dietéticas y las intervenciones de actividad física versus control sobre los cambios en la puntuación z del IMC, el IMC y los eventos adversos en niños menores de 18 años

-

evaluación del efecto de las intervenciones educativas dietéticas versus las intervenciones de actividad física sobre los cambios en la puntuación z del IMC, el IMC y los eventos adversos en niños menores de 18 años.

Los objetivos secundarios fueron examinar las características de los programas y las estrategias para responder a la pregunta: "¿Qué funciona para quién, por qué y a qué coste?". Los objetivos secundarios incluyen la evaluación de las características sociodemográficas, los indicadores del proceso (como la intensidad, la duración, el contexto y la administración de la intervención) y los factores contextuales que podrían contribuir al resultado de las intervenciones. Los objetivos específicos incluyen:

-

evaluación de las características sociodemográficas de los participantes (estado socioeconómico, género, edad, grupo étnico, ubicación geográfica, etc.);

-

evaluación de determinados indicadores del proceso (es decir, los que describen por qué y cómo ha funcionado una determinada intervención).

Métodos

Criterios de inclusión de estudios para esta revisión

Tipos de estudios

Se incluyeron los datos de ECA que se diseñaron para, o tenían la intención subyacente de, prevenir la obesidad. Se incluyeron los ECA con un período de intervención activa de cualquier duración, siempre que los estudios informaran los datos de los resultados del seguimiento a un mínimo de 12 semanas desde el inicio del estudio. Se incluyeron los ECA que asignaron al azar a individuos o grupos de individuos; sin embargo, en el caso de los ECA con asignación al azar grupal, solo se incluyeron los ECA con seis o más grupos. Los ECA se categorizaron principalmente según el grupo de edad objetivo (cero a cinco años, seis a 12 años y 13 a 18 años). Se excluyeron los ECA publicados antes de 1990. La evidencia global indica que la prevalencia del sobrepeso y la obesidad en los niños, incluidos los niños en edad preescolar, comenzó a aumentar a finales de los años ochenta (de Onis 2010; GBD Obesity Collaboration 2014). Debido al tiempo transcurrido entre la concepción, la financiación y la finalización de los ECA, se consideró la fecha de publicación de 1990 como un punto de partida pragmático y razonable para la literatura en el área.

Tipos de participantes

Se incluyeron ECA de niños con una edad media de menos de 18 años al inicio del estudio. Se incluyeron los ECA en los que los niños formaban parte de un grupo familiar que recibía la intervención si la evaluación de los resultados se podía extraer por separado para los niños. Para reflejar un enfoque de salud pública que reconozca la prevalencia de un rango de peso dentro de la población general de niños, se incluyeron los ECA en los que entre los participantes se incluyeron niños con sobrepeso u obesidad. Se incluyeron los ECA que restringieron la elegibilidad según el peso si la elegibilidad no estaba limitada a los niños con obesidad. También se incluyeron los ECA en los que los niños estaban "en riesgo" de obesidad, por ejemplo, los padres tuvieron o tenían sobrepeso, o los niños tenían bajos niveles de actividad física. Los ECA que solo incluyeron niños con obesidad al inicio del estudio se consideraron centrados en el tratamiento en lugar de la prevención y, por lo tanto, se excluyeron. Se excluyeron los ECA de intervenciones diseñadas para prevenir la obesidad en mujeres embarazadas y los ECA diseñados para niños con una enfermedad crítica o comorbilidades graves.

Tipos de intervenciones

Estrategias

Se incluyeron estrategias educativas, de promoción de la salud, psicológicas, familiares, de terapia conductual, de asesoramiento y de gestión.

Intervenciones incluidas

Se incluyeron varios tipos de intervenciones dietéticas o de actividad física, o ambas. Se incluyeron los ECA de intervenciones de dieta y nutrición, o ejercicio y actividad física, o ambos; las intervenciones también pueden haber incluido otros elementos como cambio en el estilo de vida (p.ej., cambios en la conducta sedentaria o el sueño) y apoyo social. Se incluyeron los ECA de alimentación complementaria, cuyo objetivo era promover un peso saludable en bebés y niños pequeños. También se incluyeron las intervenciones dirigidas a aumentar las habilidades motoras en los niños pequeños, donde la justificación de estas intervenciones se basó en la evidencia de que las mayores habilidades motoras en los niños pequeños dan lugar a mayores niveles de actividad física a medida que el niño crece. Se excluyeron los ECA en los que la justificación de la intervención era diferente a la prevención de la obesidad.

Contexto

Se incluyeron intervenciones en cualquier contexto. Éstas incluyeron intervenciones dentro de la comunidad en general (incluidos los contextos religiosos), la atención escolar y extraescolar, el hogar, la atención sanitaria y el cuidado de los niños o el preescolar, la guardería y el jardín de infancia.

Tipos de comparaciones

Se incluyeron los ECA que compararon intervenciones dietéticas o de actividad física, o ambas, con un grupo control sin intervención que no recibió tratamiento o recibió atención habitual u otra intervención activa (es decir, comparaciones directas).

Personal de la intervención

No hubo restricciones sobre quién realizó las intervenciones, por ejemplo, investigadores, médicos de atención primaria (médicos generales), profesionales nutricionistas/dietistas, maestros, profesionales de la actividad física, organismos de promoción de la salud, departamentos de salud, líderes religiosos u otros.

Indicadores de la teoría y procesos

Se recopilaron datos sobre los indicadores del proceso y la evaluación de la intervención, la teoría de la promoción de la salud que sustenta el diseño de la intervención, los modos de estrategias y las tasas de deserción de estos estudios. Cuando fue posible, se comparó si el efecto de la intervención varió según estos factores. Esta información se incluyó en los análisis descriptivos y se utilizó para guiar la interpretación de los hallazgos y las recomendaciones.

Intervenciones excluidas

Se excluyeron los ECA de intervenciones diseñadas específicamente para el tratamiento de la obesidad infantil y los ECA diseñados para tratar los trastornos alimentarios como la anorexia y la bulimia nerviosas Se excluyeron todas las intervenciones farmacológicas o quirúrgicas, ya que son intervenciones de tratamiento. Se excluyeron los ECA que se centraron de manera exclusiva en la lactancia materna o el biberón; por ejemplo, los ECA que solo evaluaron el efecto de diversos niveles de proteínas en las fórmulas infantiles. También se excluyeron los ECA que solo se centraron en el entrenamiento de fuerza y el acondicionamiento físico (no dirigidos a la prevención de la obesidad).

Tipos de medida de resultado

Para que los estudios se incluyeran, debían informar uno o más de los siguientes resultados primarios mediante la presentación de una medición inicial y una posterior a la intervención. Esta revisión se centró en informar resultados antropométricos (resultados primarios) y en enumerar otros resultados.

Resultados primarios

-

puntuación z del IMC/IMC

-

Prevalencia de sobrepeso y obesidad

-

Peso y talla

-

Índice ponderal

-

Porcentaje de contenido de grasa

-

Grosor del pliegue cutáneo

Resumen de los hallazgos

Se presentan las tablas "Resumen de los hallazgos", en las que se informa la puntuación z del IMC, el IMC y los eventos adversos para los tres grupos de edad de los niños (de cero a cinco años, de seis a 12 años y de 13 a 18 años) y tres tipos de intervención (dieta, actividad física, y combinación de dieta y actividad física).

Métodos de búsqueda para la identificación de los estudios

Búsquedas electrónicas

We searched the following databases for this update and for previous versions of this review. We did not exclude studies based on language.

For the 2015 update (in this review we included and synthesised data from all studies identified)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2010, Issue 1 to 2016 Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library

-

MEDLINE (Ovid) January 2010 to June 2015

-

Embase (Ovid) January 2010 to June 2015

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Ovid) March 2010 to June 2015

-

PsycINFO (Ovid) 2010 to June 2015

For the 2018 update (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for studies identified as potentially relevant from screening titles and abstracts)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 6 to 2018, Issue 1), in the Cochrane Library

-

MEDLINE (Ovid) June 2015 to January 2018

-

Embase (Ovid) June 2015 to January 2018

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Ovid) June 2015 to January 2018

-

PsycINFO (Ovid) June 2015 to January 2018

Complete search strategies and search dates for each database can be found in the Appendices.

-

Update 2018 (Appendix 1). Potentially relevant studies stored in Studies awaiting classification

-

Update 2015 (Appendix 2). All study data assessed for inclusion and synthesised

-

Update 2010 (Appendix 3). All study data assessed for inclusion and synthesised

-

Update 2005 (Appendix 4). All study data assessed for inclusion and synthesised

Búsqueda de otros recursos

For the 2018 update on 22 January 2018 we searched ClinicalTrials.gov with the filter 'Applied Filters: Child (birth–17)' . We also searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, search portal (ICTRP), using the filter for studies in children. In addition, we scanned the reference lists of key systematic reviews and references of included studies.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Selección de los estudios

For the 2015 update, one review author (TB) performed title and abstract screening, and another review author (CS) checked a random subsample (10%). For the 2018 update, two review authors (TB and ME) independently assessed all titles and abstracts in duplicate using RAYYAN software (Rayyan‐QCRI 2016). For titles and abstracts that potentially met the inclusion criteria, we obtained the full text of the article for further evaluation. Two review authors (from TB, CO and ME), independently assessed the full‐text reports of studies against a list of criteria for inclusion. We resolved differences in opinion or uncertainty through a process of discussion. Occasionally we brought in a third review author (CS, TM).

Extracción y manejo de los datos

We developed a data extraction form, based on the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for quantitative studies (Thomas 2003), with additional data extraction items specifically related to implementation. For studies identified between 2010 and 2015 we extracted information relevant to equity using the PROGRESS (Place, Race, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socio‐economic status (SES), Social status) checklist (Ueffing 2009). And to facilitate full understanding of interventions we also incorporated items from the TIDieR checklist and guide (Hoffman 2014). We also extracted information relevant to assessing risk of bias, source and involvement of funders, data on indicators of intervention process and evaluation, health promotion theory underpinning intervention design, modes of strategies, and attrition rates. Two review authors (CO, TB) independently extracted data from included papers into the data extraction form for each study.

This review sought to identify studies that had reported on socio‐demographic characteristics known to be important from an equity perspective using the PROGRESS checklist (Ueffing 2009).

We attempted to capture factors that we could use to assess implementability of the interventions. These included: programme reach (i.e. was the intervention available to all those to whom it would be relevant?); programme acceptability (was the intervention acceptable to the target population?); and programme integrity (was the programme implemented as planned?). A comprehensive process evaluation allowed us to monitor variability in context and delivery, and to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Evaluación del riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos

We assessed the risk of bias of included RCTs using the 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2017). At least two review authors assessed each study as being at ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’ risk of bias for each item. Review authors were not blinded with respect to study authors, institution or journal. We used discussion and consensus to resolve any disagreements.

We incorporated performance and detection bias under the item 'blinding' in the 'Risk of bias' tool. We assessed this to be at low risk for RCTs that reported blinding of outcome assessors, and high risk for RCTs reporting that outcome assessors were not blinded.

We assessed RCTs as low risk for attrition bias if an adequate description of participant flow through the study was provided, the proportion of missing outcome data was relatively balanced between groups and the reasons for missing outcome data were provided and we considered them unlikely to bias the results. We assessed RCTs ‘high’ risk for attrition if attrition was 30% or greater at final follow‐up.

For cluster‐randomised trials we made an additional assessment listed as ‘other bias’ based on the advice for dealing with cluster‐RCTs (Higgins 2011a). For ‘timing of recruitment of clusters’, we rated RCTs at ‘high’ risk of bias if the studies had recruited the clusters after randomisation and at ‘low’ risk of bias if recruitment occurred before randomisation.

For selective outcome reporting we searched for both trial registrations and protocols. Where we were unable to find a trial registration or protocol, we recorded 'selective outcome reporting' as unclear. If all relevant primary outcomes reported in the study report or protocol were reported in the results of the paper, we marked these as low risk of bias. If relevant primary outcomes reported in the study report or protocol were not reported (in the results paper) we recorded these as high risk of bias. Where studies reported an outcome in the results paper that they had not prespecified in the protocol or trials register, we reported this as high risk of bias. For RCTs where we could not locate a protocol or trial registration document, we recorded risk of bias as unclear. See Table 8.5 and Section 8.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Medidas del efecto del tratamiento

For this update we focused on reporting the results for the anthropometric outcomes and listed other outcomes. We conducted meta‐analyses to investigate the impact of included interventions on zBMI scores and BMI. We did not undertake a meta‐analysis of the effects of the interventions on prevalence of overweight or obesity. Most of the RCTs did not report prevalence and used highly variable methods for the classification of overweight and obesity. Different methods of classification of weight status in children produce very different prevalence estimates, and so limit comparisons between RCTs.

Cuestiones relativas a la unidad de análisis

We assessed each cluster‐RCT to see if the analysis had accounted for clustering. For any studies that had not adjusted for clustering we created an approximate analysis of the cluster‐RCT by inflating the standard errors (SE) See section 16.3.6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). This method requires the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (ICC), an estimate of the variability within and between clusters, for the RCT. Where a study does not report this, it is possible to use an external estimate of ICC. We selected external estimates of 0.02 and 0.04 by looking at the ICCs reported in other cluster‐RCTs, discounting extremes and looking at the published literature (Ukoumunne 1999). We ran sensitivity analyses using 1) no adjustment, 2) adjustment for clustering assuming ICC of 0.02, and 3) adjustment for clustering assuming ICC of 0.04. We did this for both BMI and zBMI. All values of unadjusted SE and approximate adjusted SE plus data required to calculate them are listed in Appendix 5.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

For RCTs with more than one intervention group we considered 1) if all the intervention groups were relevant to the review, and 2) if all the intervention groups were relevant for a specific meta‐analysis. In situations where only one intervention group was relevant to the meta‐analysis, we would treat it as a two‐armed RCT. For RCTs with more than two arms of relevance to the same meta‐analysis and with one control arm, we included data from both treatment arms. To avoid double counting of participants we halved the number of participants in the control arm. For factorial RCTs we included all the arms of the trials as if they were distinct trials. See Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions Section 16.5.4 and 16.5.6 (Higgins 2011a).

Manejo de los datos faltantes

We noted missing data on the data extraction form and took them into account when judging the risk of bias of each study. We excluded RCTs for which insufficient data were available from quantitative analyses (e.g. in study reports, and when missing data could not be obtained). We did not impute any missing data.

Evaluación de la heterogeneidad

We used I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity (Higgins 2003) using suggested assessments of heterogeneity such that I2 of 0 % to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity. We decided to pool data whatever the value of I2 statistic indicated in the meta‐analysis and to explore heterogeneity by running subgroup analyses using different variables, for example, setting, duration of intervention, type of intervention to see if variability could be explained. For our 'Summary of findings' table, and given the varied nature of intervention types, setting, and characteristics of baseline populations, we chose to downgrade evidence once for RCTs with greater than 60% value for I2 statistic and to downgrade evidence twice for RCTs with greater than 85% value of I2 statistic. For the main analyses we will not use the Chi2 or I2 statistics to assess differences between the subgroups for BMI or zBMI. We consider the age groups to be distinct populations, and therefore assessment of differences between the three age groups is not appropriate for the purposes of this review (Deeks 2017).

Evaluación de los sesgos de notificación

We assessed reporting bias and other small study effects following methods set out in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Higgins 2011d. For those meta‐analyses with more than 10 studies we prepared funnel plots using Stata version 15 (Stata 2019), and tested for asymmetry with Egger tests (Egger 1997a), using the commands 'metabias' and 'metafunnel' Harbord 2009.

Síntesis de los datos

We analysed zBMI scores and BMI data using the generic inverse variance method with a random‐effects model (Deeks 2017). The order of preference for data was prespecified. In preference we took difference in means between intervention and control that were reported for the end of the intervention and had been adjusted for clustering or baseline variation, or both. However, if only unadjusted data were available we used those. If difference in mean data were unavailable we used change scores: the change in outcome from baseline to follow‐up (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, chapter 9.4.5.2; Deeks 2017). If standard deviation (SD) was not reported we derived it, where possible, from 95% confidence intervals, P values or SE, using the calculator provided in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014)), and equations provided in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2017). We did not use data from RCTs where the difference in means between the two arms at baseline was more than the change in mean in either arm (suggesting that the baseline measure would dominate the outcome data) unless the study presented the change (and variance of that change) for each arm, or had adjusted for the baseline difference.

For RCTs that reported more than one intervention arm, we presented the data for each intervention arm compared with the control arm, with the number of participants in the control arm halved to ensure no double counting.

We have presented only outcome data reported immediately post‐intervention. We did not analyse data for subsequent post‐intervention follow‐up.

We have presented analyses stratified by age group with three categories: 0 to 5 years, 6 to 12 years, and 13 to 18 years. This was based on what would be meaningful for decision makers. These age categories correspond to stages of child development and childhood settings. We believe the populations, children aged 0 to 5 years, children aged 6 to 12 years and young people aged 13 to 18 years, to be too different developmentally to be considered as a single sample. Interventions that are likely to work on a 3 or 4 year old, are unlikely to work in adolescents, and vice versa. We present the effects of BMI and zBMI for each of the three age groups as the main analyses in this review.

For cluster‐RCTs that had not adjusted for clustering we approximated analysis for clustering using ICC = 0.04, based upon methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a), and on sensitivity analyses of the value of ICC to use for the approximation: 1) no clustering or ICC = 0, 2) ICC of 0.02, and 3) ICC of 0.04. This is described in more detail in section Unit of analysis issues, and in Sensitivity analysis. See Appendix 5 for lists of unadjusted and approximately adjusted SE.

Análisis de subgrupos e investigación de la heterogeneidad

We explored heterogeneity in the nine primary analyses:

-

age 0 to 5 years: dietary interventions, physical activity interventions, and combined dietary and physical interventions; zBMI and BMI;

-

age 6 to 12 years: dietary intervention, physical activity interventions, and combined dietary and physical interventions; zBMI and BMI;

-

age 13 to 18 years: dietary intervention, physical activity interventions, and combined dietary and physical interventions; zBMI and BMI.

by two subgroup analyses, 1) main setting of the intervention (childcare/preschool, school, health service, wider community, home), and 2) duration of active intervention period (≤ 12 months, > 12 months).

GRADE and 'Summary of findings' table

We created 'Summary of findings' tables to summarise the size and certainty of effects of the interventions. This was based on the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). We used GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT 2015), and followed methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Section 8.5 (Higgins 2017), and Chapter 12 (Schünemann 2017).

To determine the consistency of effects for each comparison we looked at the I2 statistic value. For comparisons where the meta‐analysis had an I2 statistic value above 60% we determined these to be at ‘serious’ inconsistency. If the I2 statistic was above 85% we considered this to be ‘very serious’ inconsistency. We assessed the risk of bias across all the RCTs contributing to the pooled effect. We assessed the effect of risk of bias by comparing the overall treatment effect from all studies with a sensitivity analysis in which we excluded all studies with at least one domain at high risk of bias. If the estimates from the overall versus the sensitivity analysis were in opposite directions, we downgraded the estimate twice for risk of bias rating it as 'very serious'. If the treatment effects from the overall analysis and the sensitivity analysis were largely congruent then we did not downgrade.

Análisis de sensibilidad

Fifteen cluster‐RCTs had not accounted for clustering in their analysis (Annesi 2013; Bonis 2014; Cao 2015; Farias 2015; Herscovici 2013; Klein 2010; Lazaar 2007; Llargues 2012; Melnyk 2013; Natale 2014; Robbins 2006; Sallis 1993; Sevinc 2011; Spiegel 2006; Thivel 2011). Three of these studies did not contribute data to any meta‐analyses (Farias 2015; Sallis 1993; Sevinc 2011). We approximated adjustment for clustering using the method described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We selected a range of ICC coefficients (no adjustment, ICC = 0.02 and ICC = 0.04). We ran meta analyses using unadjusted SE and SE adjusted for ICC = 0.02 and ICC = 0.04 for both BMI and zBMI. Using sensitivity analysis, we observed that the pooled effect sizes for each meta‐analysis was changed very little by the choice of value for ICC (see Appendix 5). In order to be conservative in our selection of ICC we chose an ICC of 0.04 and have presented pooled meta‐analyses in which the SE of RCTs that had not taken account of clustering have been approximately adjusted using an ICC of 0.04.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

This is the fourth update of this review, the search dates for which were 1999, 2002, 2005, 2010, and 2015. The 2010 to 2015 search retrieved 18,106 unique new records. We read 279 of these records in full and added 108 new RCTs. In total, since 1999, searches for this review have retrieved 46,107 unique records, and we have included 153 RCTs (210 papers). See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow chart (Moher 2009). There are 62 RCTs (n = 88,383) contributing data to meta‐analysis of zBMIs and 72 RCTs (n = 77,286) contributing data to meta‐analysis of BMI. Note, these figures do not add up to 153 (to reflect number of included studies) because some studies report both zBMI and BMI whilst other studies report neither. Twenty‐four RCTs reported both BMI and zBMI scores. The records retrieved from searching and the RCTs identified since 1999 appear to be increasing exponentially (see Figure 2). We ran the searches for a fifth update (search date January 2018) and have listed papers with potential for inclusion identified from this search in 'Studies awaiting classification'. However, we have not yet synthesised data from these studies in this review.

Flow of records

Increase in number of records retrieved and studies included in this systematic review from 2001 until 2017

Included studies

We included 153 RCTs in this review. We have listed details of each in the Characteristics of included studies table and Figure 3, and have summarised additional material relating to the theory underpinning the intervention, setting, age, country, and intervention period in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. Information about type of comparator is listed in Table 4 and information related to funding source is summarised in Table 5. We have listed studies reporting adverse events in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8. We have summarised included studies reporting zBMI or BMI, and therefore included in the meta‐analyses, in Table 9, and we have listed them in more detail in Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15.

Distribution of studies by location, age of children and type of intervention. * Total number of locations is 154 and not 153 (number of studies) as one study, Lana 2014, was located in both Spain and Mexico. Papadaki 2010 was located in 7 countries across Europe.

| Study | Type | Country | Theory | Setting | |||||

| Childcare/ preschool | Primary/ secondary school | Health Service | Community | Home | Duration of intervention | ||||

| Alkon 2014 | D and PA | USA | NR | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Annesi 2013 | PA | USA | Social Cognitive and Self‐efficacy Theory | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Barkin 2012 | D and PA | USA | Social Cognitive Theory, Transtheoretical Model of Change | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Bellows 2013a | PA | USA | NR | X | > 12 months | ||||

| Birken 2012 | PA (screen time) | Canada | NR | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Bonis 2014 | D and PA | USA | NR | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Bonuck 2014 | D (bottle use) | USA | NR | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Bonvin 2013 | PA | Switzerland | Socioecological Model | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Campbell 2013 | D and PA | Australia | Social Cognitive Theory | X | > 12 months | ||||

| Crespo 2012 | D and PA | US‐Mexico border | Social Cognitive Theory and Health Belief Model | X | X | X | ≤ 12 months | ||

| Daniels 2012 | D | Australia | Attachment theory, Anticipatory Guidance, Social Cognitive Approach | X | > 12 months | ||||

| De Bock 2012 | D | Germany | Social Learning Theory and Exposure theory | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| De Coen 2012 | D and PA | Belgium | Socio‐ecological model | X | > 12 months | ||||

| Dennison 2004 | PA | USA | Behaviour change | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| De Vries 2015 | PA | Netherlands | NR | X | X | ≤ 12 months | |||

| Feng 2004 | D and PA (education only) | China | NR | X | > 12 months | ||||

| Fitzgibbon 2005 | D and PA | USA | Social Cognitive Theory | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Fitzgibbon 2006 | D and PA | USA | Social Cognitive Theory | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Fitzgibbon 2011 | D and PA | USA | Social Cognitive Theory, Self‐determination theory | X | X | ≤ 12 months | |||

| Haines 2013 | D and PA | USA | NR | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Harvey‐Berino 2003 | D and PA | USA | Behaviour Change | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Keller 2009 | D and PA | Germany | NR | X | X | ≤ 12 months | |||

| Klein 2010 | D and PA | Germany | Theory of Planned Behaviour, Precaution Adoption Process | X | > 12 months | ||||

| Mo‐suwan 1998 | PA | Thailand | Environmental Change | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Natale 2014 | D and PA | USA | Socio‐ecological model | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Nemet 2011 | D and PA | Israel | NR | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Ostbye 2012 | D and PA | USA | Social Cognitive Theory | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Paul 2011 | D | USA | NR | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Puder 2011 | D and PA | Switzerland | Social Ecological model | X | > 12 months | ||||

| Reilly 2006 | PA | Scotland | Environmental Change and Behaviour Change | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Roth 2015 | PA | Germany | NR | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||

| Rush 2012 | D and PA | New Zealand | NR | X | > 12 months | ||||

| Skouteris 2016 | D and PA | Australia | Learning and Social Cognitive Theories | X | ≤ 12 months | ||||