Apoyo conductual adicional como complemento a la farmacoterapia para el abandono del hábito de fumar

Resumen

Antecedentes

Las farmacoterapias para el abandono del hábito de fumar aumentan la probabilidad de lograr la abstinencia en un intento de abandono. Es verosímil que la provisión de apoyo o que, si se brinda apoyo, la provisión de apoyo más intensivo o que incluya componentes particulares, puedan aumentar de manera adicional la abstinencia.

Objetivos

Evaluar el efecto de agregar o aumentar la intensidad del apoyo conductual a las personas que utilizan fármacos para el abandono del hábito de fumar y evaluar si los efectos son diferentes según el tipo de farmacoterapia o la cantidad de apoyo en cada condición. También se examinaron los estudios que compararon directamente intervenciones conductuales pareadas por tiempo de contacto, en las que la ambos grupos recibieron farmacoterapia (p.ej. evidencia de diferentes componentes o enfoques para el apoyo conductual como complemento a la farmacoterapia).

Métodos de búsqueda

Se realizaron búsquedas en el Registro especializado del Grupo Cochrane de Adicción al Tabaco, clinicaltrials.gov y el ICTRP en junio de 2018 de registros con cualquier mención de la farmacoterapia, incluido cualquier tipo de tratamiento de reemplazo de nicotina (TRN), bupropión, nortriptilina o vareniclina que evaluara el agregado de apoyo personal o comparara dos o más intensidades de apoyo conductual.

Criterios de selección

Ensayos controlados aleatorios o cuasialeatorios en los que todos los participantes recibieron farmacoterapia para el abandono del hábito de fumar y las condiciones difirieron en cuanto a la cantidad de apoyo conductual. La condición intervención tenía que incluir el contacto persona a persona (definido como en persona o por teléfono). La condición control podía recibir un contacto personal menos intensivo, un tipo diferente de contacto personal, información escrita o ningún apoyo conductual en absoluto. Se excluyeron los ensayos que solo reclutaron embarazadas y los ensayos que no planificaron evaluar el abandono del hábito de fumar durante seis meses o más.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Para esta actualización el examen y la extracción de los datos siguieron los métodos Cochrane estándar. La medida de resultado principal fue la abstinencia de fumar después de al menos seis meses de seguimiento. Se utilizó la definición más rigurosa de abstinencia para cada ensayo, y cuando fue posible, las tasas de validación bioquímicas. Se calculó el cociente de riesgos (CR) y el intervalo de confianza (IC) del 95% para cada estudio. Cuando fue apropiado se realizó un metanálisis con un modelo de efectos aleatorios.

Resultados principales

Ochenta y tres estudios, 36 de los cuales fueron nuevos para esta actualización, cumplieron los criterios de inclusión e incluyeron 29 536 participantes. En general, se consideró que 16 estudios tuvieron bajo riesgo de sesgo y 21 estudios alto riesgo de sesgo. Los otros estudios se consideraron como de riesgo de sesgo incierto. Los resultados no fueron sensibles a la exclusión de los estudios con riesgo alto de sesgo. Se agruparon todos los estudios que compararon más apoyo versus menos apoyo en el análisis principal. Los hallazgos demostraron un efecto beneficioso del apoyo conductual además de la farmacoterapia. Cuando se agruparon todos los estudios de terapia conductual adicional, hubo evidencia de un efecto beneficioso estadísticamente significativo del apoyo adicional (CR 1,15; IC del 95%: 1,08 a 1,22; I²= 8%, 65 estudios, n = 23 331) para la abstinencia al seguimiento más largo, y este efecto no fue diferente cuando se compararon los subgrupos según el tipo de farmacoterapia o la intensidad de contacto. Este efecto fue similar en el subgrupo de ocho estudios en los que el grupo control no recibió apoyo conductual (CR 1,20; IC del 95%: 1,02 a 1,43; I²= 20%, n = 4018). Diecisiete estudios compararon intervenciones pareadas por tiempo de contacto, pero que difirieron en cuanto a los componentes conductuales o los enfoques empleados. Las 15 comparaciones tuvieron números pequeños de participantes y eventos. Solo una detectó un efecto estadísticamente significativo que favoreció al enfoque de educación sanitaria (que los autores describieron como orientación estándar que contenía información y asesoramiento), en comparación con el enfoque de entrevistas motivacionales (CR 0,56; IC del 95%: 0,33 a 0,94; n = 378).

Conclusiones de los autores

Hay evidencia de certeza alta de que la provisión de apoyo conductual en persona o por vía telefónica a las personas que utilizan farmacoterapias para dejar de fumar aumenta las tasas de abandono. Es posible que el aumento de la cantidad de apoyo conductual incremente las probabilidades de éxito en cerca del 10% al 20%, según una estimación agrupada de 65 ensayos. El análisis de subgrupos indica que el efecto beneficioso gradual del incremento del apoyo es similar en un rango de niveles de apoyo inicial. Se necesitan más estudios de investigación para evaluar la efectividad de los componentes específicos que comprenden el apoyo conductual.

PICOs

Resumen en términos sencillos

¿Más apoyo aumenta el éxito entre las personas que utilizan fármacos para dejar de fumar?

Antecedentes

Se ha demostrado que los fármacos (incluidos todos los tipos de tratamiento de reemplazo de nicotina, bupropión y vareniclina) ayudan a las personas a que dejen de fumar, y a las personas que buscan ayuda para dejar de fumar a menudo se les ofrecen estas medicaciones (farmacoterapia). El apoyo conductual también les ayuda a dejar de fumar. El apoyo conductual puede incluir un asesoramiento breve o una orientación más intensiva, y se les puede proporcionar en persona frente a frente o en grupos, o por teléfono, incluidas "las líneas para dejar de fumar" No está claro cuánto beneficio adicional se logra al agregar el apoyo, o al prestar un apoyo más intensivo, a las personas que usan fármacos como ayuda para dejar de fumar.

Características de los estudios

Se buscaron los estudios que incluyeron fumadores y proporcionaron u ofrecieron fármacos a cada uno de ellos. Las personas en los estudios luego se dividieron al azar en grupos que recibieron diferentes cantidades o tipos de apoyo conductual. Para evaluar si el apoyo brindado ayudó a que las personas dejaran de fumar, los estudios tenían que contar el número de personas que no fumaban después de seis meses o más. No se examinaron los estudios que solo incluyeron a embarazadas.

Resultados clave

Se buscaron estudios en junio 2018. Se incluyeron 83 estudios con casi 30 000 personas. La mayoría de los estudios incluyeron personas que deseaban dejar de fumar, pero una cantidad pequeña de estudios ofrecieron apoyo a personas que no estaban tratando de dejarlo. La combinación de los resultados de 65 ensayos indicó que el aumento de la cantidad de apoyo conductual a las personas que utilizaban fármacos para dejar de fumar aumenta las probabilidades de dejar de fumar. Cerca del 17% de las personas en los grupos que recibieron menos o ningún apoyo dejaron de fumar, en comparación con cerca del 20% en los grupos que recibieron más apoyo. Es útil proporcionar cierto apoyo a través de contactos personales, en persona o por teléfono. Pocos estudios compararon diferentes tipos de apoyo. Se necesitan más estudios de investigación para determinar si algunos tipos de apoyo conductual ayudan a más personas que utilizan fármacos para dejar de fumar.

Calidad de la evidencia

Se consideró que la calidad general de la evidencia fue alta, lo que significa que es muy poco probable que los estudios de investigación adicionales cambien los resultados. Esta revisión se ha actualizado dos veces y en ambas los resultados fueron muy similares, aunque se agregaron muchos estudios nuevos.

Conclusiones de los autores

Summary of findings

| Behavioural interventions as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People using smoking cessation pharmacotherapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed successful quitters without intervention | Estimated quitters with intervention | |||||

| Pharmacotherapy (with variable level of behavioural support) | Additional behavioural support (in addition to pharmacotherapy) | |||||

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | Study population1 | RR 1.15 | 23,331 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Effect very stable over time: updates of this analysis (15 new studies added 2015; 18 new studies added 2019) have had minimal impact on the effect estimate. Little evidence of differences in effect based on amount of support or type of pharmacotherapy provided. | |

| 171 per 1000 | 197 per 1000 | |||||

| The estimated rate of quitting with behavioural intervention (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed quit rate in the control group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Based on the control group crude average 2Sensitivity analysis removing studies at high risk of bias yielded results consistent with those from the overall analysis. A funnel plot was inconclusive but suggested there may have been slightly more small studies with large effect sizes than with small effect sizes. However, asymmetry was not clear and we did not downgrade on this basis; given the large number of included studies and the degree of homogeneity between them, it is unlikely that smaller unpublished studies showing no effect, if they existed, would significantly alter our results. | ||||||

Antecedentes

Descripción de la afección

Dejar de fumar es la manera más efectiva para las personas que fuman de reducir el riesgo de muerte prematura y discapacidad. Las personas que fuman necesitan dejar el hábito cuanto antes mediante ayudas basadas en la evidencia para aumentar sus probabilidades de éxito. Estas ayudas incluyen el apoyo conductual y las farmacoterapias.

Descripción de la intervención

Las intervenciones de apoyo conductual varían desde materiales escritos que contienen asesoramiento sobre dejar el hábito a programas de tratamiento grupales en múltiples sesiones u orientación individual repetida en persona o por teléfono. La provisión de materiales estándar de autoayuda solo parece tener un efecto pequeño sobre el éxito, pero hay evidencia convincente de un efecto beneficioso de los materiales de autoayuda individualmente adaptados o del asesoramiento o la orientación más intensivos (Lancaster 2017; Livingstone‐Banks 2019). También hay evidencia convincente de que los productos para el tratamiento de reemplazo de nicotina (TRN), la vareniclina y el bupropión aumentan el éxito a largo plazo de los intentos para dejar de fumar (Cahill 2016; Hartmann‐Boyce 2018; Hughes 2014).

De qué manera podría funcionar la intervención

Las guías de práctica clínica recomiendan que los profesionales sanitarios ofrezcan a las personas que están preparadas para intentar dejar de fumar farmacoterapia y apoyo conductual. Se considera que ambos tipos de tratamiento tienen vías complementarias de acción, y que mejoran de manera independiente las probabilidades de mantener la abstinencia a largo plazo (Cofta‐Woerpel 2007; Hughes 1995). Aunque las guías recomiendan el apoyo intensivo para mejorar las tasas de abstinencia, también se reconoce que muchas personas no asistirán a las sesiones múltiples. Los productos para el TRN están disponibles sin prescripción en muchos países, y las personas que los adquieren pueden no tener acceso al apoyo conductual específico. Las personas que obtienen prescripciones para las farmacoterapias pueden recibir algún apoyo, pero éste se puede centrar en explicar el uso adecuado del fármaco y no en la asesoría. Por lo tanto, puede ser que la provisión de apoyo conductual adicional aumente las tasas de abandono por encima de las que se observan con la farmacoterapia sola administrada a las personas.

Por qué es importante realizar esta revisión

Otras revisiones del Grupo Cochrane de Adicción al Tabaco evaluaron la evidencia en las intervenciones conductuales y farmacéuticas de manera individual (Cahill 2016; Hartmann‐Boyce 2018; Hughes 2014; Lancaster 2017; Livingstone‐Banks 2019; Matkin 2019; Stead 2017). Estas revisiones limitaron la inclusión a los ensayos en los que las intervenciones no presentaban factores de confusión. Los ensayos de farmacoterapias deben brindar la misma cantidad de apoyo conductual (materiales, asesoramiento, contactos de orientación) a todos los participantes, independientemente de si reciben tratamiento activo, placebo o ninguna medicación. Asimismo, cuando se evalúan las intervenciones conductuales no debe haber diferencias sistemáticas en cuanto a la oferta de fármacos entre los brazos activo y control del ensayo. Solo las revisiones que evalúan intervenciones administradas por proveedores específicos (p.ej. enfermeras, Rice 2017), o en contextos específicos (p.ej. hospitales, Rigotti 2012), pueden incluir ensayos de intervenciones que combinan terapias conductuales y diversos fármacos (p.ej. TRN, bupropión, vareniclina).

Esta revisión es una de dos que identifican sistemáticamente los ensayos de intervenciones que combinan farmacoterapias efectivas (TRN, vareniclina, bupropión, nortriptilina) con apoyo conductual (materiales adaptados, asesoramiento breve, orientación en persona o telefónica). Esta revisión evalúa los ensayos que comparan diferentes niveles de intervenciones conductuales para las personas que reciben cualquier farmacoterapia para el abandono del hábito de fumar, para proporcionar una estimación de la efectividad de la intensificación del apoyo conductual como complemento a la farmacoterapia y, como tal, se superpone con algunas revisiones separadas que evalúan los tipos de intervención incluidos aquí (p.ej. Matkin 2019), que incluyen estudios de terapias conductuales relevantes por sí mismos y como complementos a la farmacoterapia. La revisión complementaria (Stead 2016) incluye ensayos en los que una intervención que combina farmacoterapia y apoyo conductual se compara con atención estándar o con una intervención conductual breve sin farmacoterapia.

Objetivos

Evaluar el efecto de agregar o aumentar la intensidad del apoyo conductual a las personas que utilizan fármacos para el abandono del hábito de fumar y evaluar si los efectos son diferentes según el tipo de farmacoterapia o la cantidad de apoyo en cada condición. También se examinaron los estudios que comparan directamente intervenciones conductuales pareadas por tiempo de contacto, y en los que la farmacoterapia se le proporciona a ambos grupos (p.ej. evidencia de diferentes componentes o enfoques para el apoyo conductual como complemento a la farmacoterapia).

Métodos

Criterios de inclusión de estudios para esta revisión

Tipos de estudios

Ensayos controlados con asignación aleatoria o cuasialeatoria.

Tipos de participantes

Se incluyeron los ensayos que reclutaron personas que fumaban, en cualquier contexto. Se excluyeron los ensayos que solo reclutaron embarazadas; esta población se considera en Coleman 2015. Los participantes de los ensayos no necesitaban haber sido seleccionados según su interés para dejar de fumar, ni según si eran apropiados para la farmacoterapia. Sin embargo, como la farmacoterapia se ofreció o se proporcionó, era de esperar que los participantes estuvieran relativamente motivados y preparados para utilizar la medicación como parte del intento para dejar de fumar.

Tipos de intervenciones

Se incluyeron los ensayos de intervenciones de abandono del hábito de fumar en los que todos los participantes tuvieron acceso a una farmacoterapia para el abandono del hábito de fumar (incluida la TRN, la vareniclina, el bupropión y la nortriptilina, o una combinación o elección de estos) y en los que una o más condiciones intervención recibieron más apoyo conductual intensivo que la condición control. A los participantes del grupo control se les podía ofrecer cualquier nivel de apoyo, desde mínimo (p.ej. información escrita proporcionada como parte de la prescripción de la medicación), hasta orientación en múltiples sesiones. La intervención podía utilizar tipos diferentes o adicionales de contenidos de la terapia (p.ej. terapia cognitivo conductual, entrevistas motivacionales). El apoyo adicional tenía que incluir el contacto persona a persona, que podía ser en persona o por teléfono. En esta actualización también se incluyeron los ensayos que probaron componentes conductuales específicos que utilizaron un control pareado con respecto a la frecuencia y la duración del contacto.

Tipos de medida de resultado

Según la metodología estándar del Grupo Cochrane de Adicción al Tabaco, el resultado primario fue el abandono del hábito de fumar al seguimiento más largo y según la definición más estricta de abstinencia, es decir, de preferencia la abstinencia mantenida a la prevalencia puntual, y la que utilizó las tasas bioquímicamente validadas, cuando estuvieron disponibles. Además, se señaló cualquier otro resultado de abstinencia informado, y se realizaron análisis de sensibilidad si la elección del resultado en un estudio pudo haber alterado los resultados del metanálisis. Se excluyeron los estudios en los que no se planificó evaluar el abandono del hábito de fumar a los seis meses o más.

Métodos de búsqueda para la identificación de los estudios

We identified trials from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group's Specialised Register (the Register), and the clinical trials registries: clinicaltrials.gov, and the ICTRP. The Register is generated from regular searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO, for trials of smoking cessation or prevention interventions. We ran our most recent searches in June 2018. At the time of the search, the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 1, 2018; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20180531; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201824; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 201800528. See the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group website for full search strategies and list of other resources searched.

We searched the Register for records with any mention of pharmacotherapy, including any type of NRT, bupropion, nortriptyline or varenicline in title, abstract or indexing terms (see Appendix 1 for the final search strategy). We checked titles and abstracts to identify trials of interventions for smoking cessation that combined pharmacotherapy with behavioural support. We also considered for inclusion trials with a factorial design that varied both pharmacotherapy and behavioural conditions. For the first version of this review, we also tested an additional MEDLINE search using the smoking‐related terms and design limits used in the standard Register search and the MeSH terms ‘combined modality therapy’ or (Drug Therapy and (exp Behavior therapy or exp Counseling)). This search retrieved a subset of records already screened for inclusion in the Register, and was used to assess whether it might retrieve studies where there was no mention of a specific cessation pharmacotherapy in the title, abstract or indexing. We did not find any additional studies from this approach, and so did not use it for subsequent updates.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Selección de los estudios

For this version of the review, two reviewers (BH, HW, JHB) independently screened all studies for inclusion, with disagreements resolved by discussion or referral to a third reviewer.

Extracción y manejo de los datos

For this version of the review, two reviewers (BH, HW, JHB, CM, JLB) independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias for each included study, with disagreements resolved by discussion or referral to a third reviewer. We extracted the following information:

-

Country and setting of trial

-

Study design

-

Method of recruitment, including any selection by motivation to quit

-

Characteristics of participants including gender, age, smoking rate

-

Characteristics of intervention deliverer

-

Common components: type, dose and duration of pharmacotherapy

-

Intervention components: type and duration of behavioural support

-

Control group components: type and duration of behavioural support

-

Outcomes: primary outcome length of follow‐up and definition of abstinence, other follow‐up and abstinence definitions, use of biochemical validation, adverse events

-

Sources of funding & potential conflicts of interest

-

Information used to assess risk of bias (see below)

Evaluación del riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos

We evaluated studies on the basis of the randomisation procedure, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data assessment and any other bias using the standard Cochrane methods (Cochrane Handbook 2011). We also judged studies on the basis of detection bias, according to standard methods of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. For trials of behavioural interventions (such as those included here), it is not relevant to assess performance bias as blinding of participants and personnel is not feasible due to the nature of the intervention. In these trials, we assessed detection bias based on the outcome measure; e.g. if the outcome was objective (biochemically‐validated) or if contact was matched between arms, or both, we judged the studies as having low risk of bias, but if the outcome was self‐reported and the intervention arm received more support than the control arm, we judged differential misreport to be possible and rated these studies as having high risk of bias.

Medidas del efecto del tratamiento

We expressed trial effects as a risk ratio (RR) (calculated as: quitters in treatment group/total randomised to treatment group)/(quitters in control group/total randomised to control group), alongside 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A risk ratio greater than 1 indicates a better outcome in the intervention group than in the control condition.

Cuestiones relativas a la unidad de análisis

We included both individually and cluster‐randomised trials. In extracting data from cluster‐randomised trials, we considered whether study authors had made allowance for clustering in the data analysis reported, and planned to use data adjusted for clustering effects, where available.

Manejo de los datos faltantes

We reported numbers lost to follow‐up by group in the 'Risk of bias' table. Following standard Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group methods, we assumed people lost to follow‐up to be smoking and included them in the denominators for calculating the risk ratio. We have reported any exceptions to this assumption in the 'Risk of bias' table. We noted separately any deaths during follow‐up and excluded them from denominators.

Evaluación de la heterogeneidad

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). As guided by Higgins 2003, we considered a value greater than 50% as evidence of substantial heterogeneity.

Evaluación de los sesgos de notificación

We used funnel plots to assess small‐study effects and investigate the possibility of publication bias.

Síntesis de los datos

For groups of trials where we judged meta‐analysis appropriate, we pooled RRs using a Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects model, and reported a pooled estimate with a 95% CI.

If trials had more than one intervention condition, we compared the most intensive combination of behavioural support and pharmacotherapy to the control in the main analysis.

We categorised the intensity of behavioural support in both intervention and control conditions based on two of the categories used in the US Guidelines (Fiore 2008): ‘Total amount of contact time’ (Categories: 0, 1 to 30*, 31 to 90, 91 to 300, > 300 minutes (*guideline categories '1 to 3' and '4 ‐ 30' combined for this review)) and ‘Number of person‐to‐person sessions’ (Categories: 0*, 1 to 3*, 4 to 8, > 8 (*guideline categories '0 to 1', and '2 to 3' combined for this review)). Additionally we used the number and duration of contacts as continuous predictors in meta‐regression, described below.

Análisis de subgrupos e investigación de la heterogeneidad

We used the difference in average intensity of support (number or duration of contacts) between intervention and control conditions as the main potential feature to explain any heterogeneity. In an exploratory analysis new to this version of the review, we planned to use a non‐linear meta‐regression model in R version 3.5.2 (R program) to explore the effect of difference in number and duration of contacts on intervention effect, anticipating that differences in the intensity of support would have the largest impact when the amount of contact in the control group was smallest. However, graphs of intervention effect against these factors did not provide evidence of this non‐linear trend, and so instead results were presented graphically and summarised using a standard meta‐regression model with each of the factors as a linear predictor. Studies where the intensity of support could not be determined for one or more treatment groups were excluded from the meta‐regression.

Análisis de sensibilidad

We considered whether the main results were sensitive to the exclusion of studies at high risk of bias in any domain. We also considered whether the definition and duration of follow‐up or the inclusion of intermediate‐intensity arms in trials with more than two relevant arms had any impact on treatment effect.

Summary of findings table

Following standard Cochrane methodology, we created a 'Summary of findings' table for our primary outcome using the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome, and to draw conclusions about the certainty of evidence within the text of the review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

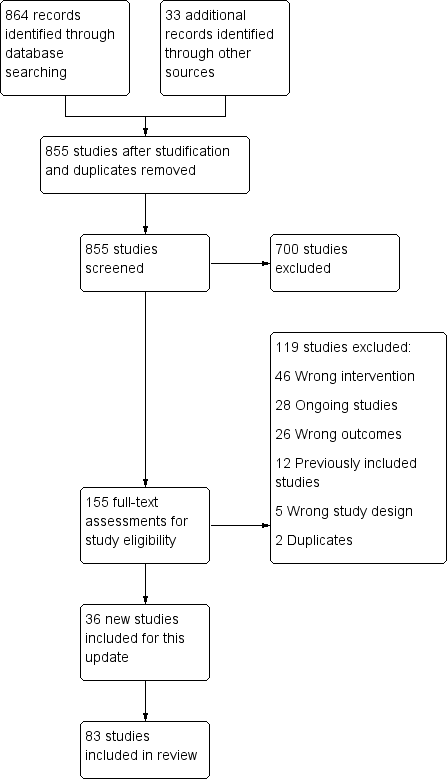

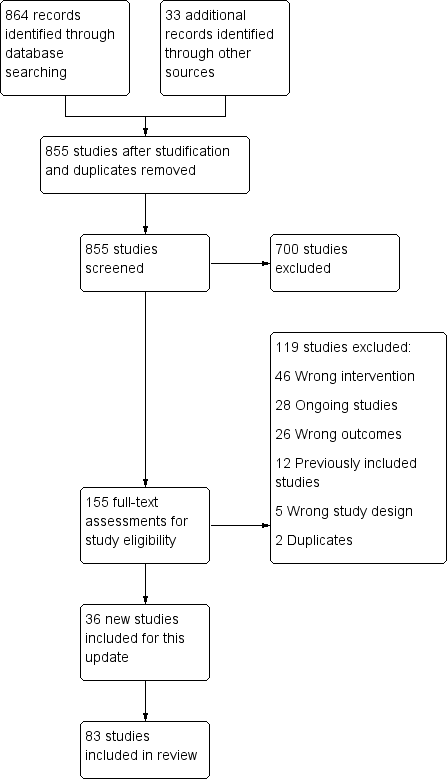

Our combined searches for all versions of this review retrieved approximately 3837 records. We excluded most of them as not relevant based on title and abstract. Of the records that did relate to trials of interventions for smoking cessation, most were not relevant because they were placebo‐controlled trials of pharmacotherapies, in which the behavioural support was the same for intervention and control conditions. We identified 83 studies for inclusion and listed 63 as excluded. We identified 36 ongoing studies. Further studies of combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural support that did not offer pharmacotherapy to the control group are included in Stead 2016. Some studies had multiple study arms and contributed to both Stead 2016 and to this review. The flow of studies is reported in Figure 1.

Study flow diagram for 2019 update

Included studies

We identified 83 studies as relevant for inclusion, of which 36 were new for the 2019 update. 29,536 participants are now included in relevant arms of these studies. Details of each study are given in the Characteristics of included studies table, and a summary of intervention and control group characteristics in Table 1.

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

| Study ID | Pharmacotherapy | Modality (included face‐to‐face/ telephone only) | Number of contacts | Total duration (minutes) | Number of contacts | Total duration (minutes) | Comments |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 120 | 6 | 120 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 16 | 4290 | 1 | 30 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 140 | 4 | 80 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 19 | 950 | 10 | 500 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 17 | 1050 | 17 | 290 | ||

| NRT | Telephone | 5 | 100 | 5 | 100 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 112 | 7 | 112 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 285 | 7 | 105 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 20 | 400 | 20 | 880 | Exercise sessions/time excluded | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | Unclear | 1 | Unclear | ||

| Choice | Face‐to‐face | 9 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | ||

| NRT | Telephone | 5 | 90 | 5 | 90 | ||

| NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 22 | 970 | 12 | 720 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 220 | 6 | 87.5 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 4 | 240 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 2 | 120 | 1 | 5 | Intervention also had "access to 5 web‐based booster sessions" | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 11 | 130 | 0 | 0 | Multifactorial ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 100 | 1 | Unclear | ||

| Choice | Face‐to‐face | 6 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Telephone | 6 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| Choice | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 125 | 4 | 30 | ||

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 20 | Unclear | 1 | 60 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 2 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 14 | 1050 | 4 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 14 | 1050 | 5 | 300 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 1200 | 5 | 450 | ||

| Nortriptyline | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 1200 | 5 | 450 | ||

| Bupropion/Nortriptyline | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 450 | 4 | 30 | ||

| NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 11 | 330 | 5 | Unclear | Multifactorial study design | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 195 | 6 | 105 | ||

| NRT | Telephone | 4 | 100 | 1 | 15 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 450 | 5 | 225 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 300 | 1 | 'Brief' | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 210 | 6 | 210 | ||

| NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 300 | 10 | 200 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 320 | 8 | 80 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 420 | 7 | 420 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 48 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 20 | 736.5 | 4 | 82.5 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 2 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Telephone | 5 | 60 | 0 | 0 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 8 | 480 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 540 | 6 | 540 | ||

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 13 | Unclear | 13 | Unclear | Control received 80 minutes less contact than intervention | |

| NRT & Varenicline | Face‐to‐face | 9 | Unclear | 5 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 45 | 2 | 15 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 600 | 5 | 100 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 105 | 1 | 12.5 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 240 | 1 | 20 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 36 | 1080 | 36 | 1080 | Intervention group: "exercise counselling delivered while the participant was engaged in exercise" ‐ have left this time in as also counselling | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 64 | 1985 | 59 | 1860 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | Unclear | 3 | 45 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | 65 | 3 | 35 | ||

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 9 | 540 | 1 | 15 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 12 | 320 | 4 | 200 | Multifactorial study design | |

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 420 | 7 | 420 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 195 | 1 | 10 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 90 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Telephone | 4 | 67 | 4 | 60 | Exact duration of contact not recorded, but averages given, intervention: 67.0 (± 25.8), control: 60.1 (± 23.9) | |

| Varenicline | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 5 | Unclear | Comparing culturally‐tailored with standard counselling ‐ duration of sessions not stated | |

| NRT | Telephone | See note | See note | 0 | 0 | Control = "access to quitline"; intervention = "up to 12 calls" ‐ averaged 7 calls at 9 minutes each | |

| NRT | Telephone | 8.2 | 80 | 0 | 0 | Intervention numbers based on average number/duration of calls | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | Unclear | 3 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | 65 | 2 | 5 | Control offered "up to 2 visits", intervention only offered 3rd visit if ready to quit | |

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 12 | 1440 | 12 | 1440 | ||

| Bupropion | Telephone | 4 | Unclear | 1 | 7.5 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| Varenicline | Telephone | 5 | 67 | 0 | 0 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 12 | 270 | 10 | 150 | ||

| Varenicline | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 120 | 1 | 20 | Duration of sessions not stipulated, but maximum amounts recorded in paper. Intervention: 120, control: 20 | |

| Choice | Telephone | 6 | 150 | 0 | 0 | Intervention sessions listed as 20 to 30 minutes ‐ control was referral to a quitline, but there were no mandated sessions, so contact listed as 0 | |

| Vidrine 2016 (CBT) | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 960 | 4 | 40 | Vidrine study intervention 2 (control split) |

| Vidrine 2016 (MBAT) | NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 960 | 4 | 40 | Vidrine study intervention 1 (control split) |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 12 | Unclear | 12 | Unclear | Sessions' duration not reported | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 9 | 945 | 9 | 945 | Exact duration not listed, but approximate range given | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 210 | 6 | 180 | Compared 2 interventions, less intensive counted as control | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | Unclear | 1 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 24 | 1080 | 9 | 180 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 240 | 4 | 240 | ||

| Choice | Face‐to‐face | 14 | 730 | 9 | 150 | ||

Study setting, participant recruitment and motivation

Twenty‐nine studies were conducted in a healthcare setting (excluding smoking cessation clinics); this included ten studies in primary care (Aveyard 2007; Bock 2014; Cook 2016; Ellerbeck 2009; Fiore 2004; Ockene 1991; Schlam 2016; Smith 2014; Stanton 2015; Van Rossem 2017; Wagner 2016), one in a chest clinic (Tonnesen 2006), one in a cardiovascular disease outpatient clinic (Wiggers 2006), one in a rheumatology clinic (Aimer 2017), one in an immunology clinic (Stanton 2015), three in HIV clinics (Lloyd‐Richardson 2009; Humfleet 2013; O'Cleirigh 2018), one in a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health centre (Matthews 2018), one in mental health clinics (Williams 2010), one in a mental health research centre (Baker 2015), three in substance abuse clinics (Lifrak 1997; Rohsenow 2014; Stein 2006), two in a Veterans Administration hospital (Brody 2017; Simon 2003), and three in cardiac wards (Berndt 2014; Busch 2017; Hasan 2014) or any ward (Warner 2016).

Since the intervention included the provision of pharmacotherapy, many of the studies recruiting in a healthcare setting recruited volunteers who were interested in making a quit attempt, but motivation to quit was not always an explicit eligibility criterion. Wiggers 2006 used a motivational interviewing approach and participants did not all make quit attempts. Ockene 1991 offered nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and participants were not initially selected by motivation, and Ellerbeck 2009 included a small proportion of people in the 'precontemplation stage' of the transtheoretical model.

A further four studies recruited members of health maintenance organisations (HMOs) (Boyle 2007; Lando 1997; Swan 2003; Swan 2010). Boyle 2007 proactively recruited HMO members who had filled a prescription for smoking cessation medication, while the others sought volunteers by advertising to HMO members. Universities or research facilities were the study sites for five studies (Baker 2015;Bloom 2017; Prapavessis 2016; Schmitz 2007a; Webb Hooper 2017).

Forty studies recruited community volunteers interested in quitting, including three which recruited people who were attending cessation clinics (Alterman 2001; Rovina 2009; Yalcin 2014). The study setting was not explicitly stated in four studies (LaChance 2015; Macpherson 2010a; Strong 2009; Vidrine 2016).

One study recruited adolescents (Bailey 2013); all other studies were conducted in adults.

Characteristics of intervention and control conditions

Pharmacotherapy

NRT was offered in the majority of studies, with 41 providing nicotine patch only. While most of these provided a supply of NRT for between eight and 12 weeks, three studies offered only a two‐week supply (Bricker 2014; MacLeod 2003; Warner 2016). Eight studies used nicotine gum only (Ahluwalia 2006; Ginsberg 1992; Hall 1985; Hall 1987; Hall 1994; Huber 2003; Ockene 1991; Wewers 2017), one used sublingual tablets (Tonnesen 2006), and three did not specify the type (Aimer 2017; Bushnell 1997; Wagner 2016). Five studies offered patch and/or gum (Bricker 2014; Cook 2016; Humfleet 2013; Schlam 2016; Smith 2013a). Seven studies provided bupropion alone (Cropsey 2015; Gifford 2011;McCarthy 2008; Rovina 2009; Schmitz 2007a; Strong 2009; Swan 2003), one provided nortriptyline alone (Hall 1998) and four provided varenicline alone (NCT00879177; Smith 2014; Swan 2010; Van Rossem 2017). Three studies offered a choice of pharmacotherapy; NRT or bupropion (Boyle 2007; Ellerbeck 2009), or NRT, bupropion, or varenicline (Yalcin 2014). Gariti 2009 randomised participants to NRT or bupropion using a double‐dummy design. Hall 2002 randomised participants to either bupropion or nortriptyline (placebo arms not used in this review). Three studies provided combination therapy of both NRT and bupropion (Hall 2009; Killen 2008; Vander Weg 2016).

Behavioural support

The intensity of the behavioural support, in both the number of sessions and their duration, was very varied for both intervention and control conditions.

In seven trials, there was no counselling contact for the controls: in six, participants received pharmacotherapy by mail (Boyle 2007; Ellerbeck 2009; MacLeod 2003; Solomon 2000; Solomon 2005; Vander Weg 2016), and in Fiore 2004 there was no counselling or advice for the control group although there was face‐to‐face contact with study staff. In 30 studies, the control arms had between one and three contacts (which could be face‐to‐face or by telephone) and most of these had a total contact duration of between four and 30 minutes, although three had between 31 and 90 minutes contact scheduled (Gifford 2011; Lando 1997; Reid 1999). In 34 studies, the control group was scheduled to receive between four and eight contacts, with all except eight (Aveyard 2007; Bricker 2014; Cook 2016; Gariti 2009; Kim 2015; Smith 2013a; Vidrine 2016; Wu 2009) involving a total contact duration of over 90 minutes. Twelve studies offered over eight contacts for the controls (Bailey 2013; Baker 2015; Begh 2015; Bloom 2017; Brody 2017; McCarthy 2008; Patten 2017; Prapavessis 2016; Strong 2009; Webb Hooper 2017; Williams 2010; Yalcin 2014).

Typically, the intervention involved only a little more contact than the control, so that the most intensive interventions were compared with more intensive control conditions. In five trials, the intervention consisted of between one and three sessions, with a total duration of 31 to 90 minutes in most of them (Calabro 2012; Rohsenow 2014; Stein 2006; Wiggers 2006), although Calabro 2012 also provided access to a tailored internet programme. Warner 2016 offered a brief (under 5 minutes) quitline facilitation intervention. Forty‐five studies tested interventions of between four and eight sessions, about half of which were in the 91 to 300 minute‐duration category. The remaining 32 studies offered more than eight sessions, typically providing over 300 minutes of counselling in total. The number of contacts planned was not always delivered, but generally using the average number delivered would not have changed the coding category. In a few cases where the number of contacts was either not specified or open‐ended, we coded the average number delivered and noted this in the Characteristics of included studies table.

In Analysis 1.2, we grouped trials by the number of intervention and control contacts. In 12 trials, the intervention and control condition fell into the same coding category for number of contacts (one to three contacts: Calabro 2012; Rohsenow 2014; Stein 2006; Wiggers 2006; four to eight contacts: Aveyard 2007; Bushnell 1997; Huber 2003; Tonnesen 2006; Wu 2009; more than eight contacts: McCarthy 2008; Williams 2010; Yalcin 2014). A summary of the number of sessions and duration for intervention and control conditions for each trial is provided in Table 1.

Length of follow‐up and definitions of abstinence

The majority of the included studies followed participants for a duration of six to 12 months from the target quit date, or entry into the study. Exceptions were Hall 2009 and Ellerbeck 2009 which each had a two‐year follow‐up, and Baker 2015 with a three‐year follow‐up. The design of the Ellerbeck study, in which participants were repeatedly offered support to quit, means that participants who had quit at the end of follow‐up would not necessarily have been quit for as long as two years. Thirty‐five studies only followed participants for six months.

The majority of studies reported abstinence as a prevalence measure, rather than requiring reported sustained abstinence, or abstinence at multiple follow‐up points. Fifteen studies did not attempt any biochemical verification of self‐reported abstinence; this is discussed further in Risk of bias in included studies.

Excluded studies

We listed 63 studies as excluded, along with reasons for their exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The majority were excluded because they provided less than six months follow‐up. Studies in which the intervention group received both pharmacotherapy and behavioural support and the control group received neither (or just brief behavioural support) were eligible for the companion review and are included or excluded there (Stead 2016).

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, we judged 16 studies to be at low risk of bias (low risk of bias across all domains) and 21 studies to be at high risk of bias (high risk of bias in at least one domain). All other studies were judged to be at unclear risk of bias. A summary of 'risk of bias' judgements can be found in Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged 24 studies to be at low risk of selection bias, based on the reported method of random sequence generation and allocation concealment. We judged three studies to be at high risk of selection bias, due to the method of sequence generation (Yalcin 2014), or allocation concealment (Berndt 2014; Brown 2013; Yalcin 2014). The remaining studies did not given enough detail on one or both of these aspects so we rated the risk of bias as unclear.

Blinding (detection bias)

Following standard Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group guidance, we did not formally assign a risk of performance bias for each trial as, due to the nature of the intervention, people providing the behavioural support could not be blinded.

We judged detection bias on the basis of biochemical validation of abstinence and, where biochemical validation was not provided, on the basis of differential levels of contact. Twelve studies were judged to be at high risk of detection bias as outcomes were via self‐report only and the intervention and control arms received different levels of support, making differential misreport possible (Aimer 2017; Berndt 2014; Boyle 2007; Cook 2016; Hollis 2007; MacLeod 2003; Ockene 1991; Otero 2006; Solomon 2005; Swan 2003; Swan 2010; Vander Weg 2016). The remainder of studies were judged to be at low risk for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow‐up is often relatively high in smoking cessation trials. If trials lost fewer than 20% of participants at longest follow‐up, we judged the risk of bias to be low in this domain. In most of the included trials, the proportion lost to follow‐up was more than 20% but losses were balanced across groups and less than 40%; for these, we also classified the risk of bias as low. We rated eight studies as having unclear risk of bias, either because attrition was not reported or because overall losses to follow‐up of greater than 20% were reported and a breakdown by treatment arm was not provided (Bushnell 1997; Hall 1994; NCT00879177; Otero 2006; Schlam 2016; Smith 2001; Strong 2009; Tonnesen 2006). We judged seven studies to be at high risk of bias due to high (> 50%) attrition overall or differential rates of attrition between arms (> 20% difference between arms), as per Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group guidance (Bock 2014; Calabro 2012; Gifford 2011; Macpherson 2010a; O'Cleirigh 2018; Smith 2014; Wagner 2016).

Other potential sources of bias

We found no studies to be at risk of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

Intensive versus less intensive or no support

When comparing more intensive versus less intensive behavioural support or to no support, we pooled 65 studies contributing data to this comparison, including a total of over 23,331 participants (note: in subgroups by intervention intensity, a slightly smaller number of studies was included as, in some cases, intensity of intervention or control group contact was not clear). There was little evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I² = 8%). Hall 2002 contributed separate data to two subgroups in the primary meta‐analysis. Seventeen of the studies had point estimates below 1, that is, with higher quit rates in the less intensive condition, but all these had wide confidence intervals (CIs) which crossed the line of no effect. Seven studies detected benefits of the intervention with confidence intervals that excluded 1. The estimated risk ratio (RR) was 1.15, with 95% CI 1.08 to 1.22. This suggests that increasing the intensity of behavioural support for people making a cessation attempt with the aid of pharmacotherapy increases the proportion who are quit at six to 12 months (Figure 3; Analysis 1.1; summary of findings Table for the main comparison).

Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up.

Subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy

Difference in pharmacotherapy

The effect size was similar across subgroups (test for subgroup differences, P = 0.45, I² = 0%). Though in some subgroups the confidence interval included no effect, this was likely to reflect the smaller number of studies and lower precision rather than a true difference in effect.

Subgroups by difference in intensity

Analysis 1.2 categorised trials based on the relative difference in the number of contacts between groups, with the subgroups with the largest contrast in intensities listed first and studies where the intensity of intervention and control fell into the same category shown last. There was little evidence of subgroup differences (P = 0.21, I² = 32%) nor was there evidence of any dose‐response. We did not repeat this approach for duration of intervention categories, as inspection suggested that the number of studies falling into different categories was small and that further subgroup analysis could be misleading.

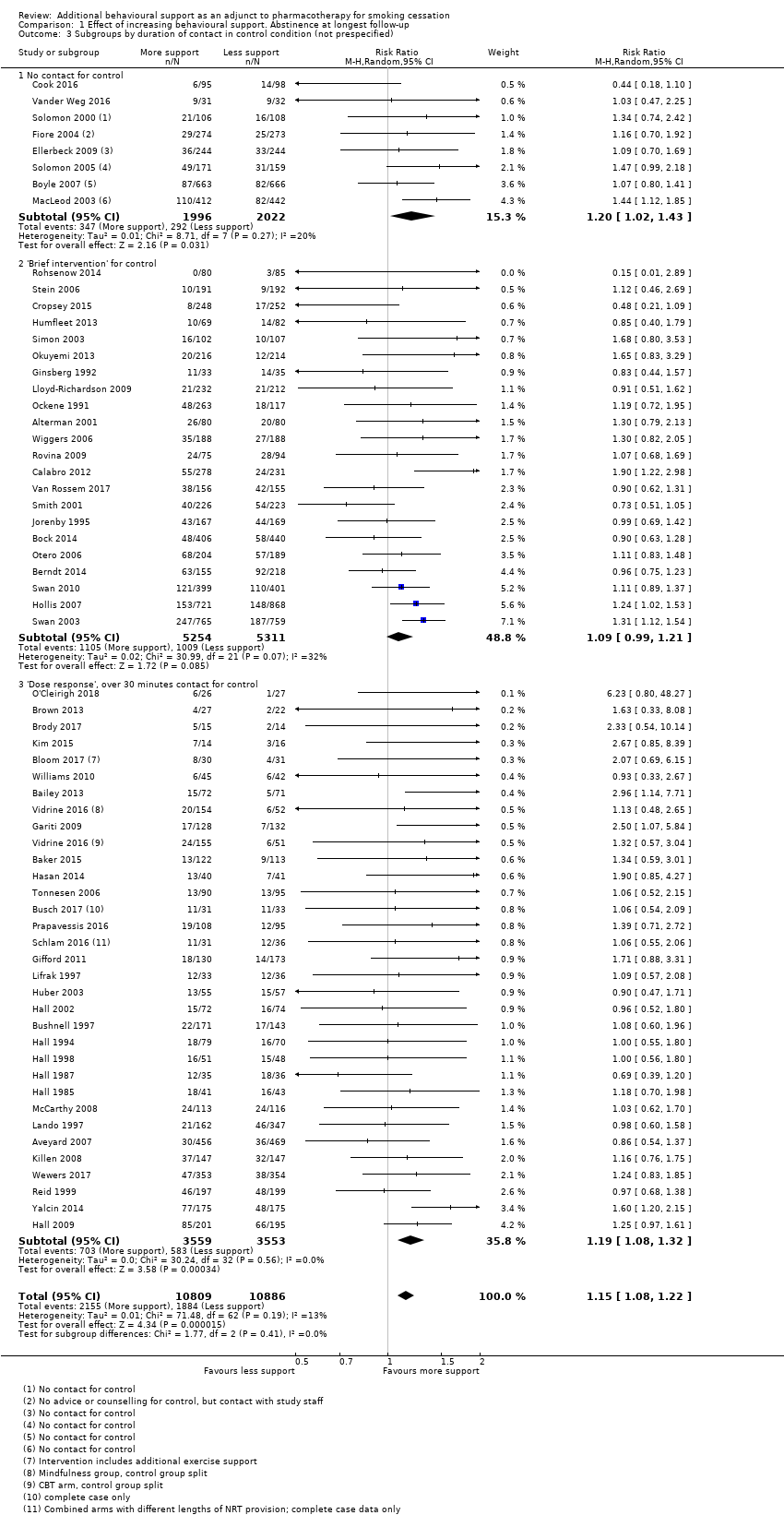

At the suggestion of a peer reviewer, we conducted two additional subgroup analyses. In Analysis 1.3, we categorised by the level of control group contact to investigate whether there might be a difference between trials where the control could be categorised as a brief intervention (up to 30 minutes) and trials which might be characterised as testing a dose‐response for behavioural support, which we defined as being where the controls received more than 30 minutes of behavioural support. The eight trials where controls had no advice or contact formed a third subgroup. Twenty‐two trials and just over half the participants were in the 'brief intervention' subgroup, and 32 trials and a third of participants were in the 'dose‐response' category. Again, there was no significant difference between the subgroups (P = 0.41, I² = 0%).

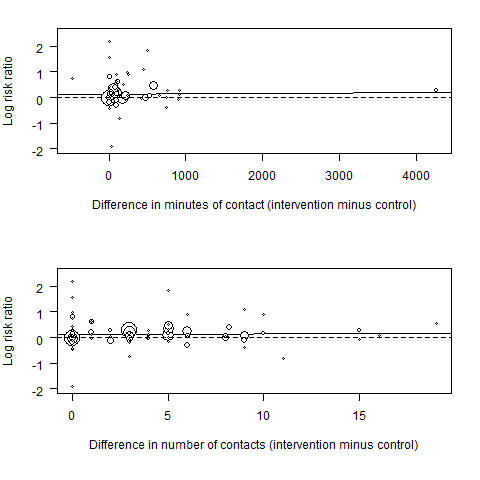

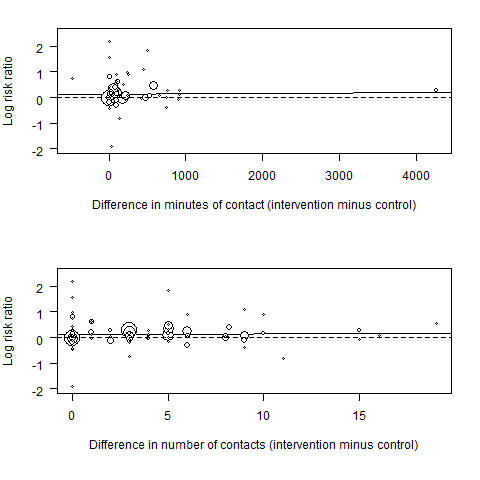

In this version of the review, we also conducted an exploratory meta‐regression to explore associations between effect sizes and number and duration of contacts. A comparison of the intervention effect (log risk ratio) by the difference between the treatment groups in the duration and number of contacts is shown in Figure 4. There was no clear effect of either increasing duration of contact (RR 1.00 per 100 minutes additional contact time, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.01) or increasing number of contacts (RR 1.00 per additional contact, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.02).

Meta‐regression results (the fitted meta‐regression trend is shown as the solid line)

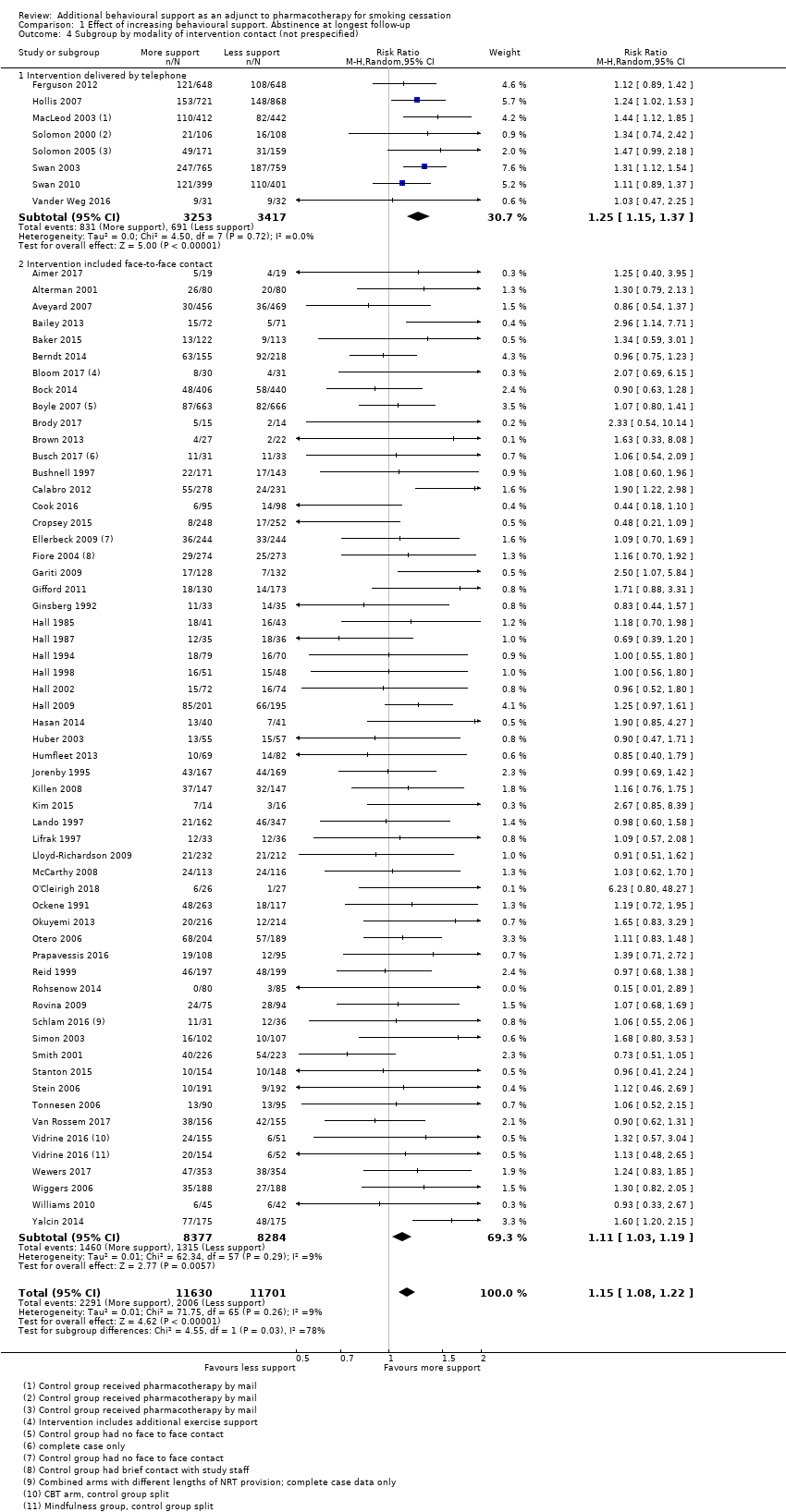

Differences in modality of intervention contact

In the second non‐prespecified analysis, we categorised studies according to whether there was some face‐to‐face contact as part of the intervention, or whether all support was given by telephone (Analysis 1.4). Here, the test for subgroup differences was significant (P = 0.03, I² = 78%), with telephone counselling showing greater relative benefit than face‐to‐face support. In the subgroup of eight studies using telephone counselling (which had some overlap with studies where there was no personal contact for the control), the point estimate was 1.25 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.37, I² = 0%, 6670 participants) in favour of additional behavioural support. In the remaining 57 studies where all intervention and most control conditions had face‐to‐face support, there was also evidence of benefit of additional behavioural support in this update, although the estimate was slightly smaller (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.19, I² = 9%; 16,661 participants).

Inclusion of medium‐intensity intervention from studies with multiple intervention conditions

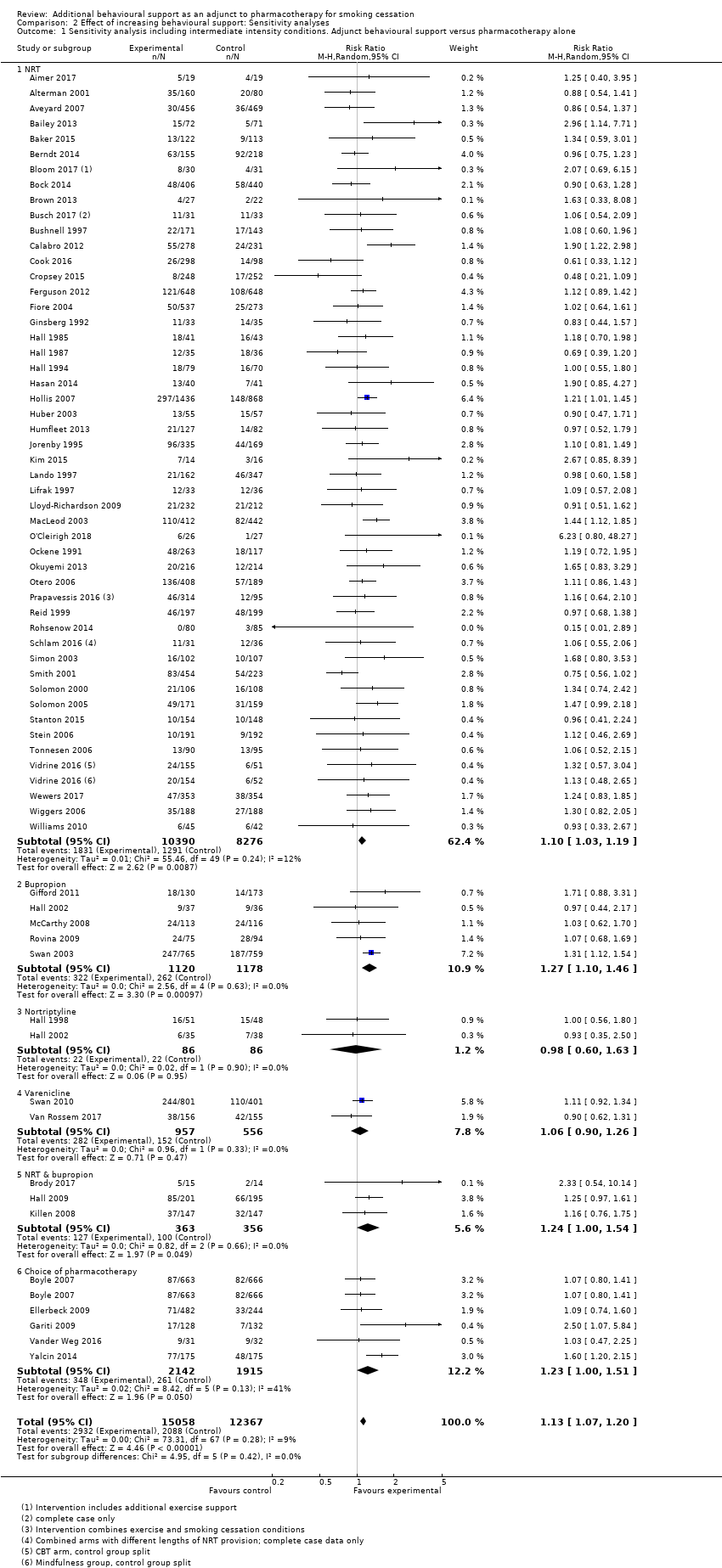

Eight studies (Alterman 2001; Ellerbeck 2009; Fiore 2004; Hollis 2007; Humfleet 2013; Jorenby 1995; Prapavessis 2016; Smith 2001; Swan 2010) included an intervention condition intermediate in intensity between the highest intensity and the control. We have not included these arms in the primary analysis in case they reduced the contrast between intervention and control. In a sensitivity analysis, we added in these arms. This had almost no impact on the estimated effect (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.20, I² = 8%; 65 studies, n = 27,425; Analysis 2.1), tending to support the finding that there was not a clear dose‐response relationship with the amount of support.

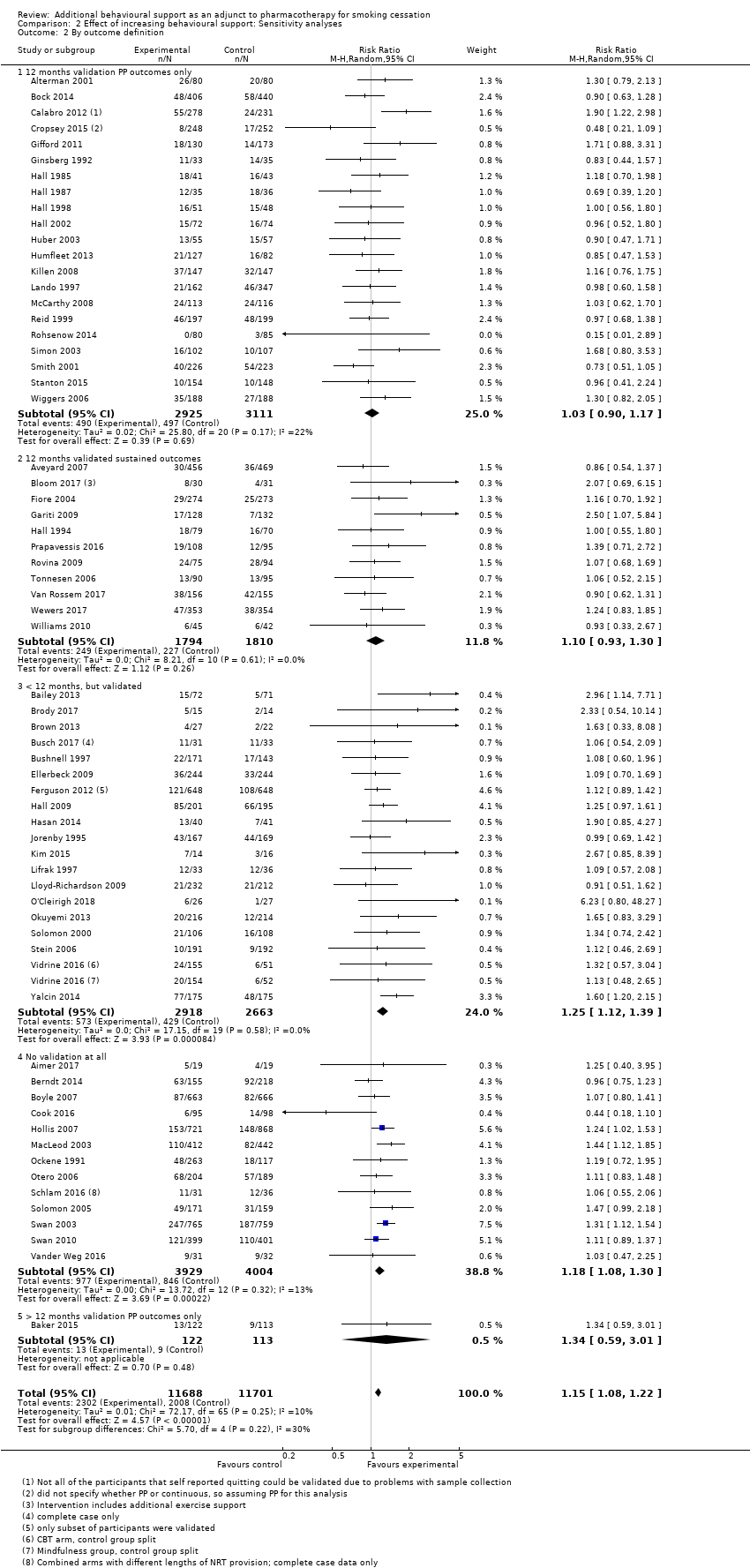

Definition of abstinence

We considered whether the way in which abstinence was defined was related to the effect size, and also to absolute quit rates. Here again, there were no significant subgroup differences (P = 0.22, I² = 30%, Analysis 2.2). Some studies that reported sustained outcomes also reported point prevalence rates, but substituting the less stringent definition did not change the overall findings. However, studies with point prevalence outcomes had, on average, higher quit rates in both intervention and control arms. A study comparing outcomes based on different abstinence definitions reported within studies found that, for pharmacotherapy studies, point prevalence and sustained abstinence outcomes were strongly related, with sustained abstinence averaging around 74% of point prevalence rates (Hughes 2010).

Unit of analysis issues

Two included studies were cluster‐randomised trials (Berndt 2014; Lando 1997). One of these (Berndt 2014) performed an analysis adjusting for clustering effects and found them to be not significantly different from zero, and so we used the original data values. The other (Lando 1997) also allowed for clustering but did not report adjusted results, and so the magnitude of clustering effects was unknown. As the number of included studies in the review was large, this was not likely to have any noticeable effect on our overall conclusions.

Risk of bias

In a sensitivity analysis, removing studies judged to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain, the effect observed was consistent with that of the main analysis (RR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.17, I² = 0%; 47 studies, n = 13355).

Studies not included in meta‐analysis

Two studies comparing more versus less intensive support were not included in the meta‐analysis due to a lack of usable data. NCT00879177 is a completed study that was not yet published at the time of searching, and while numerical data were not available, the author indicated that results were broadly comparable between groups. Wagner 2016 compared individual counselling with group counselling, and although follow‐up was conducted at later time points, the only data available at time of searching was for 12‐week quit rates, where there was no evidence of difference in quit rates (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.81; n = 400).

Studies matched for contact time

Seventeen studies compared interventions matched for contact time. Fifteen of these provided usable data, which is available in Analysis 3.1. Of the 12 comparisons, all had small numbers of participants and events. Only one, comparing motivational interviewing to health education (which the authors described as standard counselling containing information and advice), detected a statistically significant effect, in this case in favour of health education (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.94, n = 378). Only one comparison included more than one study; this group of studies compared culturally‐tailored support with non‐tailored support. Four studies (n = 929) contributed to this comparison (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.92). Statistical heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 78%) and was driven by one small study (Wu 2009; n = 139) in Chinese smokers which found a significant benefit in favour of the culturally‐tailored intervention (RR 2.26, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.49). For comparisons in which only one study contributed, see Analysis 3.1 for data and effect estimates.

A further two studies compared interventions matched for contact time but had insufficient data to be recorded in Analysis 3.1:

-

Schmitz 2007a compared cognitive behavioural therapy to standard therapy but quit rates in the control group could not be accessed.

-

Strong 2009 also compared cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to standard therapy (ST) but we could not access quit rates beyond 12 weeks. At 12 weeks, there was "no significant difference in the risk of lapse or relapse across CBT and ST psychosocial treatments" (abstinence data not reported).

Discusión

Resumen de los resultados principales

Un metanálisis que agrupó 65 estudios con un total de más de 23 000 participantes encontró evidencia de certeza alta de que la provisión de apoyo conductual más intensivo a las personas que intentaban dejar de fumar con la ayuda de la farmacoterapia aumentará habitualmente las tasas de éxito en cerca del 10% al 20% (Resumen de los hallazgos, tabla 1). Lo anterior fue cierto cuando se comparó más versus menos apoyo y cuando se comparó el apoyo conductual con ningún apoyo conductual. Este cálculo del efecto ha permanecido estable con el transcurso del tiempo: al agregar nueve ensayos en 2015, la cantidad de participantes aumentó en el 20% y, no obstante, el cociente de riesgos se mantuvo casi igual, de 1,16 a 1,17; y al agregar 18 ensayos adicionales en 2019, la cantidad de participantes aumentó en un 25% adicional y el cociente de riesgos fue 1,15. Este hecho aumenta la confianza en que existe un efecto beneficioso. Aún hay poca evidencia de la heterogeneidad estadística general, a pesar de la variabilidad en la cantidad y la naturaleza del apoyo conductual probado. Las comparaciones directas indican un efecto beneficioso de la provisión de más apoyo, independientemente del nivel inicial de apoyo proporcionado. Los análisis de sensibilidad indican que este cálculo es muy consistente. Aunque el efecto relativo por lo general es más pequeño que al probar el apoyo conductual en ausencia de farmacoterapia, es importante poner el efecto en el contexto de las condiciones control que ofrecían una farmacoterapia efectiva y, habitualmente, apoyo conductual, es decir, un nivel de apoyo compatible con las guías de mejores prácticas. Las tasas de abandono en los grupos control reflejaron este hecho, con una tasa mediana de abandono en los ensayos de alrededor del 17%, lo que significa que el aumento relativo calculado se traduce en un aumento absoluto de alrededor de dos a tres puntos porcentuales. Debido a la importancia del abandono del hábito de fumar para los resultados futuros de salud, esta es una diferencia clínicamente relevante (West 2007).

Compleción y aplicabilidad general de las pruebas

Los estudios identificados para esta revisión se han realizado en gran parte en los EE.UU. o Europa. Es posible que no haya sido posible encontrar estudios relevantes realizados en otros lugares. Los participantes fueron habitualmente fumadores moderados a empedernidos y estaban interesados en abandonar el hábito. La mayoría de los estudios reclutaron participantes que ya habían tratado de dejar de fumar varias veces. La mayor parte de la evidencia provino de estudios que probaron el apoyo en persona adicional. Los ocho ensayos que probaron agregar la orientación telefónica encontraron un efecto más fuerte a favor del contacto adicional, pero no fue posible determinar si este hallazgo se basó en verdaderas diferencias en el efecto o en otras diferencias entre los estudios.

Una posible limitación de la revisión es que el análisis entre los ensayos se centró en la cantidad de apoyo conductual en lugar de en los componentes específicos, o en la calidad de la provisión. Sin embargo, en esta actualización se incluyeron estudios que compararon directamente intervenciones pareadas según el tiempo de contacto (p.ej. probar diferentes enfoques o tipos de apoyo conductual). Solo una de las 15 comparaciones detectó un efecto significativo, pero la mayoría de las comparaciones solo incluyeron un estudio y todas las comparaciones tuvieron números pequeños de participantes. El tema de los componentes específicos del apoyo conductual y las asociaciones con la efectividad se investiga más a fondo en otra revisión Cochrane (Hartmann‐Boyce 2018a).

Certeza de la evidencia

La evidencia con respecto al apoyo conductual adicional se valoró como de certeza alta, lo que significa que es muy poco probable que los estudios de investigación adicionales cambien la confianza en el efecto. Esta valoración está apoyada por la consistencia del cálculo del efecto con el transcurso del tiempo, y es probable que sea la última actualización de esta revisión. Sin embargo, a pesar de la alta certeza en los resultados, algunas áreas relacionadas con las cinco consideraciones GRADE (riesgo de sesgo, imprecisión, falta de direccionalidad, inconsistencia y sesgo de publicación) merecen discusión; a saber, el riego de sesgo, la inconsistencia y el sesgo de publicación.

Riesgo de sesgo

Aunque se valoró que la mayoría de los ensayos tuvieron riesgo bajo o incierto de sesgo, 21 estudios se calificaron como alto riesgo de sesgo. Es alentador saber que el análisis de sensibilidad que excluyó los estudios con alto riesgo de sesgo no cambió el efecto general. La calidad de los ensayos fue la típica de los estudios de investigación sobre el abandono del hábito de fumar en general. No se evaluó formalmente si hubo riesgo de sesgo de realización debido a la falta de cegamiento de los proveedores o los participantes. El cegamiento de los proveedores no habría sido posible y fue difícil determinar si los participantes sabían cómo se comparaba su tratamiento con las otras opciones ofrecidas. Todos los participantes buscaban una farmacoterapia activa y habrían tenido conocimientos sobre dichos tratamientos (aparte de una proporción pequeña en estudios factoriales controlados con placebo). Los efectos esperados para los componentes conductuales probablemente habrían sido pequeños, y no se consideró que el efecto pequeño de las intervenciones se le pudiera atribuir completamente a las mayores expectativas en cuanto a las condiciones de intervención.

Inconsistencia

Hubo diferencias potencialmente importantes en los ensayos en cuanto a la diferencia relativa en el apoyo brindado a los grupos intervención y control. A pesar de la falta de heterogeneidad estadística, se realizaron varios análisis de subgrupos, incluidos algunos que no se preespecificaron. En respuesta a una inquietud acerca de que se estaba combinando evidencia de apoyo conductual versus ningún apoyo con evidencia de una intensidad del apoyo dependiente de la dosis, los ensayos se dividieron en los que el control no incluyó el contacto personal; los que le proporcionaron al grupo control una intervención breve, operacionalizada como un contacto de menos de 30 de minutos; y los ensayos en los que la condición control fue más intensiva (Análisis 1.3). No hubo evidencia de diferencias en el efecto relativo entre estos tres subgrupos. En esta actualización también se realizó una metarregresión exploradora en la que los resultados aún indican que la curva de respuesta a la dosis para el apoyo conductual es plana. Se establecieron conclusiones similares en una revisión complementaria a esta, en la que la farmacoterapia y el apoyo conductual combinados se compararon con el apoyo mínimo; las comparaciones indirectas entre ensayos que utilizaron intervenciones conductuales más y menos intensivas tampoco lograron detectar grandes diferencias (Stead 2016). La presente revisión también detectó un efecto beneficioso más claro con el aumento del apoyo en los estudios en los que el contacto fue telefónico, pero que tampoco se preespecificó y puede reflejar el mayor tamaño de los ensayos realizados en contextos de las líneas para dejar de fumar, o posiblemente el hecho de que la mayoría de estos estudios no utilizaron la validación bioquímica de la abstinencia.

Sesgo de publicación

Un gráfico en embudo (funnel plot) no fue concluyente, lo que indica que puede haber habido ligeramente más estudios pequeños con tamaños grandes del efecto que con tamaños pequeños del efecto (Figura 5). Sin embargo, la asimetría no fue clara y, cuando se investigó a fondo al realizar análisis de sensibilidad con la exclusión de los valores atípicos, el efecto no se alteró de manera significativa. Debido al número grande de estudios incluidos y al grado de homogeneidad entre ellos, es poco probable que estudios no publicados más pequeños que muestran efecto, si existieran, alteren de manera significativa los resultados.

Sesgos potenciales en el proceso de revisión

Se utilizó el Registro Especializado del Grupo Cochrane de Adicción al Tabaco para identificar los estudios. El Registro incluye informes de ensayos identificados de las principales bases de datos bibliográficas. No hay un término directo para el tipo de intervención de interés para la revisión, pero se examinó cualquier informe de ensayo que mencionara una farmacoterapia. Es posible que el Registro no incluya todos los informes relevantes de ensayos o que no haya sido posible identificar algunos. Los métodos para la extracción y el análisis de los datos son los utilizados para otras revisiones Cochrane. La práctica de imputar los datos faltantes como personas que fumaban se ha utilizado tradicionalmente en los estudios de investigación primarios y secundarios sobre el abandono del hábito de fumar y tiene la ventaja de que las tasas absolutas de abandono no se exageran al pasar por alto las pérdidas durante el seguimiento. El sesgo en el efecto relativo solo se introducirá si la clasificación errónea difiere entre las personas que se pierden de la condición de intervención y las personas control. Si se supone que proporcionalmente más participantes de los que se pierden en el grupo control son fumadores, pero en realidad abandonaron el hábito, entonces se sobrestimaría el efecto del tratamiento.

Acuerdos y desacuerdos con otros estudios o revisiones

La fuente principal de datos sistemáticos acerca de la respuesta a la dosis para el apoyo conductual es la Public Heath Service Clinical Practice Guideline de los EE.UU., actualizada por última vez en 2008 (Fiore 2008). Esta guía incluye metanálisis (el último actualizado en 2000) para diferentes niveles de apoyo y tiempo de contacto. Los análisis incluyeron ensayos de diferentes niveles de apoyo versus control. Mostraron tendencias hacia un aumento de los efectos en los ensayos que tuvieron más sesiones y más tiempo de contacto, en comparación con las condiciones mínimas. Por ejemplo, los efectos calculados en comparación con el contacto mínimo difirieron en los ensayos con cuatro a 30 minutos de tiempo de contacto (OR 1,9; IC del 95%: 1,5 a 2,3) y los ensayos con 91 a 300 minutos (OR 3,2; IC del 95%: 2,3 a 4,6) (Fiore 2008 Tabla 6.9) y entre dos a tres sesiones de tratamiento (OR 1,4; IC del 95%: 1,1 a 1,7) y más de ocho sesiones (OR 2,3; IC del 95%: 2,1 a 3,0), en comparación con cero y una sesión (Fiore 2008 Tabla 6.10). Estos análisis no se limitaron a las comparaciones directas (en los ensayos) de la intensidad de tratamiento. Tampoco distinguieron entre los estudios con y sin farmacoterapia, y la mayoría de los estudios del presente análisis se publicaron después de 2000, por lo que no se habrían incluido. Es probable que la presente revisión proporcione un cálculo más preciso del efecto del apoyo adicional junto con la farmacoterapia, que se basa en el análisis de los ensayos que comparan directamente diferentes niveles de apoyo.

Hay evidencia observacional de que el acceso a más apoyo conductual se asocia con un mayor éxito para dejar de fumar. Por ejemplo, un estudio de los English Stop Smoking Services en el que hubo un uso alto de la farmacoterapia, encontró una asociación positiva entre la cantidad de sesiones y las tasas de abandono a corto plazo programadas (West 2010). Un estudio de usuarios de TRN que llamaron a las líneas para dejar de fumar en California encontró que las personas que recibieron sesiones múltiples de orientación tuvieron tasas de abandono mayores después de un año (Zhu 2000).

Cada vez más, los estudios que prueban los efectos del apoyo conductual proporcionan farmacoterapia a ambos brazos. Lo anterior significa que muchos de los estudios aquí incluidos se incluyen (solo como subconjuntos) en otras revisiones de intervenciones conductuales. Dichos estudios incluyen la orientación telefónica y la orientación persona a persona, individual y en grupos (Lancaster 2017; Matkin 2019; Stead 2017). Los resultados del subgrupo de ensayos en los que se proporcionó apoyo adicional por vía telefónica son notablemente compatibles con los de la revisión Cochrane de orientación telefónica (Matkin 2019). Matkin 2019 también incluyó estudios sin farmacoterapia, por lo que tuvo significativamente más estudios que los ocho aquí incluidos, pero la estimación puntual fue la misma de la presente revisión para los estudios que reclutaron fumadores que no llamaron a las líneas para dejar de fumar (CR 1,25; IC del 95%: 1,15 a 1,35; 65 ensayos; 41 233 participantes, I²= 52%). En la revisión Cochrane de orientación conductual individual (Lancaster 2017), los efectos fueron nuevamente compatibles con los resultados: hubo evidencia de calidad moderada (disminuida debido a la imprecisión) de un efecto beneficioso moderado de la orientación cuando todos los participantes recibieron farmacoterapia (CR 1,24; IC del 95%: 1,01 a 1,51; seis estudios, 2662 participantes; I2 = 0%). El efecto fue más fuerte en los estudios en los que los participantes no recibieron farmacoterapia. De manera similar, en la revisión Cochrane de programas de terapia conductual grupal (Stead 2017), el efecto fue más fuerte en los estudios en los que los participantes no recibieron farmacoterapia; solo cinco ensayos incluyeron farmacoterapia, con un estimación puntual que indicó un efecto beneficioso moderado, pero con intervalos de confianza amplios que incluyeron el efecto nulo (CR 1,11; IC del 95%: 0,93 a 1,33; I2= 0%; n = 1523).

Finalmente, una explicación para la repercusión relativamente pequeña de la provisión de más apoyo conductual es que no se proporcionan en el momento en el que podrían ser más efectivas. La recaída después del éxito inicial es la norma para los intentos de dejar de fumar, y cuando las personas hacen llamadas adicionales es posible que ya hayan recaído. Diversos autores de estudios formularon comentaron este tema (p.ej. Reid 1999; Smith 2001). Aunque estos estudios no se caracterizan habitualmente por abordar la "prevención de las recaídas", hay una pequeña superposición entre esta revisión y la revisión Cochrane de intervenciones para la prevención de las recaídas (Livingstone‐Banks 2019a), que concluyó que no hubo evidencia de un efecto beneficioso del apoyo conductual adicional para prevenir la recaída. Por otro lado, en algunos casos el efecto beneficioso inicial de la intervención desapareció una vez que terminó el tratamiento y los autores indicaron que el apoyo prolongado adicional podría haber logrado un cambio (p.ej. Killen 2008; Solomon 2000), aunque la replicación de uno de estos estudios con apoyo más prolongado (Solomon 2005) todavía mostró el mismo patrón de recaída tardía. Otra posible explicación es que la captación para el tratamiento prolongado puede ser deficiente, de manera que es posible que el número real de contactos recibidos por grupo no haya variado de manera significativa. Pocos estudios informaron medidas de captación.

Study flow diagram for 2019 update

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up.

Subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy

Meta‐regression results (the fitted meta‐regression trend is shown as the solid line)

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, outcome: 1.1 Subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy.

Comparison 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, Outcome 1 Subgroups by type of pharmacotherapy.

Comparison 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, Outcome 2 Subgroups by contrast in number of contacts between intervention & control.

Comparison 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, Outcome 3 Subgroups by duration of contact in control condition (not prespecified).

Comparison 1 Effect of increasing behavioural support. Abstinence at longest follow‐up, Outcome 4 Subgroup by modality of intervention contact (not prespecified).

Comparison 2 Effect of increasing behavioural support: Sensitivity analyses, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis including intermediate intensity conditions. Adjunct behavioural support versus pharmacotherapy alone.

Comparison 2 Effect of increasing behavioural support: Sensitivity analyses, Outcome 2 By outcome definition.

Comparison 3 Studies matched for contact time. Abstinence at longest follow‐up point, Outcome 1 Abstinence at longest follow‐up.

| Behavioural interventions as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People using smoking cessation pharmacotherapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed successful quitters without intervention | Estimated quitters with intervention | |||||

| Pharmacotherapy (with variable level of behavioural support) | Additional behavioural support (in addition to pharmacotherapy) | |||||

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | Study population1 | RR 1.15 | 23,331 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | Effect very stable over time: updates of this analysis (15 new studies added 2015; 18 new studies added 2019) have had minimal impact on the effect estimate. Little evidence of differences in effect based on amount of support or type of pharmacotherapy provided. | |

| 171 per 1000 | 197 per 1000 | |||||

| The estimated rate of quitting with behavioural intervention (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed quit rate in the control group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Based on the control group crude average 2Sensitivity analysis removing studies at high risk of bias yielded results consistent with those from the overall analysis. A funnel plot was inconclusive but suggested there may have been slightly more small studies with large effect sizes than with small effect sizes. However, asymmetry was not clear and we did not downgrade on this basis; given the large number of included studies and the degree of homogeneity between them, it is unlikely that smaller unpublished studies showing no effect, if they existed, would significantly alter our results. | ||||||

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

| Study ID | Pharmacotherapy | Modality (included face‐to‐face/ telephone only) | Number of contacts | Total duration (minutes) | Number of contacts | Total duration (minutes) | Comments |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 120 | 6 | 120 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 16 | 4290 | 1 | 30 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 140 | 4 | 80 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 19 | 950 | 10 | 500 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 17 | 1050 | 17 | 290 | ||

| NRT | Telephone | 5 | 100 | 5 | 100 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 112 | 7 | 112 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 285 | 7 | 105 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 20 | 400 | 20 | 880 | Exercise sessions/time excluded | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | Unclear | 1 | Unclear | ||

| Choice | Face‐to‐face | 9 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | ||

| NRT | Telephone | 5 | 90 | 5 | 90 | ||

| NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 22 | 970 | 12 | 720 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 220 | 6 | 87.5 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 4 | 240 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 2 | 120 | 1 | 5 | Intervention also had "access to 5 web‐based booster sessions" | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 11 | 130 | 0 | 0 | Multifactorial ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 100 | 1 | Unclear | ||

| Choice | Face‐to‐face | 6 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Telephone | 6 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| Choice | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 125 | 4 | 30 | ||

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 20 | Unclear | 1 | 60 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 2 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 14 | 1050 | 4 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 14 | 1050 | 5 | 300 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 1200 | 5 | 450 | ||

| Nortriptyline | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 1200 | 5 | 450 | ||

| Bupropion/Nortriptyline | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 450 | 4 | 30 | ||

| NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 11 | 330 | 5 | Unclear | Multifactorial study design | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 195 | 6 | 105 | ||

| NRT | Telephone | 4 | 100 | 1 | 15 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 450 | 5 | 225 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 300 | 1 | 'Brief' | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 210 | 6 | 210 | ||

| NRT & Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 300 | 10 | 200 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 320 | 8 | 80 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 420 | 7 | 420 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 48 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 20 | 736.5 | 4 | 82.5 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 2 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Telephone | 5 | 60 | 0 | 0 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 8 | 480 | 8 | 480 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 540 | 6 | 540 | ||

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 13 | Unclear | 13 | Unclear | Control received 80 minutes less contact than intervention | |

| NRT & Varenicline | Face‐to‐face | 9 | Unclear | 5 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 5 | 45 | 2 | 15 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 10 | 600 | 5 | 100 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 105 | 1 | 12.5 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 4 | 240 | 1 | 20 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 36 | 1080 | 36 | 1080 | Intervention group: "exercise counselling delivered while the participant was engaged in exercise" ‐ have left this time in as also counselling | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 64 | 1985 | 59 | 1860 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | Unclear | 3 | 45 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | 65 | 3 | 35 | ||

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 9 | 540 | 1 | 15 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 12 | 320 | 4 | 200 | Multifactorial study design | |

| Bupropion | Face‐to‐face | 7 | 420 | 7 | 420 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 195 | 1 | 10 | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 6 | 90 | 0 | 0 | Multiple arms ‐ highest vs lowest intensity | |

| NRT | Telephone | 4 | 67 | 4 | 60 | Exact duration of contact not recorded, but averages given, intervention: 67.0 (± 25.8), control: 60.1 (± 23.9) | |

| Varenicline | Face‐to‐face | 5 | Unclear | 5 | Unclear | Comparing culturally‐tailored with standard counselling ‐ duration of sessions not stated | |

| NRT | Telephone | See note | See note | 0 | 0 | Control = "access to quitline"; intervention = "up to 12 calls" ‐ averaged 7 calls at 9 minutes each | |

| NRT | Telephone | 8.2 | 80 | 0 | 0 | Intervention numbers based on average number/duration of calls | |

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 7 | Unclear | 3 | Unclear | ||

| NRT | Face‐to‐face | 3 | 65 | 2 | 5 | Control offered "up to 2 visits", intervention only offered 3rd visit if ready to quit | |