Colaboración interprofesional para mejorar la práctica profesional y los resultados de la atención sanitaria

References

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Methods | Cluster‐randomised trial to test the effectiveness of an intervention involving non GP‐staff in GP practices, on the quality of care for patients with diabetes or cardiovascular disease. | |

| Participants | Country: Australia General practitioners, nurses, practice managers, receptionists, and other administrative staff. 60 general practices were randomised to receive a 6‐month teamwork intervention immediately (intervention, n = 637) or after 12 months (control, n = 548). | |

| Interventions | To assist non‐GP staff (e.g. nurses, administrative staff (practice managers, receptionists)) to work as a team with GPs, the intervention included a number of activities including: the use of structured appointment systems, recall and reminders, planned care, the use of roles, responsibilities, and job descriptions, as well as communication and meetings. | |

| Outcomes | Quality of care (12‐month follow‐up) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation is mentioned: “…Following baseline‐data collection, practices were stratified according to size (solo, 2 to 4 GPs or 5+ GPs) and randomised to receive the 6‐month teamwork intervention immediately, or after 12 months…”, but method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description of allocation method. |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | At baseline, the quality of care PACIC outcomes in the intervention group (3.01, SD 0.30) and control group (2.87, SD 0.34) were similar. |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Intervention and control teams look reasonably similar. Quote: "Control practices were more likely to be in an urban location compared with the intervention practices, have a lower full‐time equivalent level of practice nurses and were also more likely to have a higher score on the CCTP with more administrative functions for chronic disease managed by non‐GP staff. There were no key differences between the control and intervention practices for total levels of non‐GP staffing." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | High risk | It did not appear that there was any blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | High risk | Acknowledged sites dropped out, but ITT is not mentioned in the text. Practice level: Quote: "Of these, 69% (60/87) finally participated in the study, and three of these (3/60) withdrew at follow up…Reasons for withdrawal of three practices included concern about the extent of data collection and other reasons not pertaining to the study." Patient level: There were 3349 patients invited to participate in the study, with 2642 (79%) providing informed consent. Of these, 2552 (96.6%) returned the PACIC questionnaire at baseline, with 2135 (73.7%) completing all 20 items. To be included in the factor analysis, at least 17 questions needed to be completed, and 2438 participants met this criterion. The multilevel regression included data for which all relevant variables were available, resulting in a final sample size of 1853 patients. |

| Contamination | Low risk | Allocation was by practice, and it is unlikely that the control practices received the intervention. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All relevant outcomes in the method section (p B) were reported in the results section (p D‐E). A study protocol was not available and there was insufficient information to permit judgement of high or low risk of bias. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Cluster‐randomised trial with appropriate statistical analysis. |

| Methods | A RT of an IPC intervention aimed to determine the effectiveness of procedural checklists for surgical teams during 47 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. General surgeons were randomly assigned to an intervention (i.e. the use of the checklist) or a control group. | |

| Participants | Country: USA Ten general surgeon teams consisting of surgeons, anaesthetists and nurses. Twenty‐three patients in the control group and 24 in the intervention group. Eighteen patients dropped out between the randomisation and the analysis. | |

| Interventions | An intraoperative procedural checklist including preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative items. | |

| Outcomes | Clinical process or efficiency outcomes: length of operation, discharge status, readmission rates and technical proficiency. Collaborative behavioural outcomes: team behaviours (e.g. team communication and co‐ordination). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation was mentioned: "a total of 65 cases were randomized (by attending surgeon) to…", but method not specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description of allocation method. |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Quote: "Length of operation, discharge status, and readmission rates as indication of case outcome showed nonstatistical differences between groups." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | High risk | It did not appear that there was any blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | High risk | Acknowledged sites dropped out but ITT was not mentioned in the text. Patient level: Quote: "A total of 65 cases were randomized..." Quote: "Eighteen subjects/cases dropped out between randomization and analysis: two in the checklist group declined to use the checklist or requested that their cases be withdrawn after videotaping, three cases were excluded due to the conversion from laparoscopic to open procedure, procedure cancellations occurred in four cases, and scheduling difficulties or mechanical problems precluded participation for the nine remaining dropouts." |

| Contamination | Unclear risk | Randomised at the level of surgeon, but as noted by the authors "there exists the possibility that residents and other staff participated in both control and intervention cases and this contaminated our results" (p 1137). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All relevant outcomes in the method section (p 1132‐3) were reported in the results section (p 1133‐6). A study protocol was not available and there was insufficient information to permit judgement of high or low risk of bias. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected. |

| Methods | A RT where 22 multidisciplinary teams from five acute care hospitals were randomised to an intervention group that participated in a facilitated programme on multidisciplinary audit or a control group. | |

| Participants | Country: UK Nurses, physicians and other professionals (e.g. pharmacist, social worker, physiotherapist), service support staff (e.g. ward clerk, care assistant), and managers. A range of specialties (e.g. surgery, medicine, and nephrology) were included. There were 11 teams with a total of 77 participants in the intervention group and 11 teams with a total of 64 participants in the control group. | |

| Interventions | Five facilitated meetings over 6 months with activities designed to support multidisciplinary teams to undertake an audit. | |

| Outcomes | Collaborative audit activity. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “Teams within the same hospital were stratified on mean self‐reported KSA scores, perceived level of team collaboration and medical or surgical specialty before randomisation. The project secretary under the supervision of [a researcher] randomised 22 teams to intervention or control groups, using a computer random number generator. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "With the exception of two accident and emergency teams in different hospitals, teams from the same organisation were randomised in pairs. Other researchers were blind to allocation." |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | At baseline, both groups were equivalent for baseline variables in relation to KSA scores, and on the scores for the Collaborative Practice Scale. |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Quote: "At baseline, both groups were equivalent for all outcome variables except two. In comparison to the intervention group, the control arm reported higher levels of audit knowledge (median score 32.5 vs 25.0, z = ‐3.001, P = 0.003) and skills (median score 32.5 vs. 24.6, z = ‐ 2.990, P = 0.003). Baseline differences were adjusted for in the analysis. Baseline differences were not found for WWTs." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Two members of the research team (RB and HH) independently assessed the quality of the reports (blind to group allocation) and the percentage inter‐rater agreement did not fall below 82%." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | High risk | Practice level: Quote: "Participation in the intervention programme was associated with increased audit activity, with 9 of the 11 teams reporting improvements to care and seven teams completing the full audit cycle. In contrast, the majority of teams in the control group had made no progress with undertaking an audit and only two teams had undertaken a first data collection and implemented changes." Patient level: Results were provided about the quality of the audits in relation to their compliance with the 55 quality criteria, but no further information was provided in relation to any patient level outcomes. |

| Contamination | Low risk | Only intervention teams participated in the facilitation programme. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All relevant outcomes in the method section (p 781‐2) were reported in the results section (p 785‐7). A study protocol was not available and there was insufficient information to permit judgement of high or low risk of bias. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected. |

| Methods | Randomised trial ‐ Firm trial: patients and staff from inpatient medical wards at an acute care hospital were randomised to one of six medical wards. Three wards were allocated to the intervention group that implemented daily interdisciplinary work rounds, and three wards were allocated to the control group that continued traditional work rounds. | |

| Participants | Country: USA Interns and residents in medicine, staff nurses, nursing supervisors, respirologists, pharmacists, nutritionists, and social workers. There were 567 patients in the intervention group and 535 patients in the control group. | |

| Interventions | Daily interdisciplinary work rounds. | |

| Outcomes | Length of stay, total charges, orders for administration of aerosols. | |

| Notes | Unit of analysis error ‐ allocated intervention to wards but analysed patients without correction for clustering. However, this correction may not substantially change the conclusion because randomisation of staff and patients limits variation between clusters. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The firm system randomization procedures and their validation have been reviewed extensively in the literature. Each inpatient firm has two physician teams or ward services. For this trial the six ward services were divided so that three ward services continued traditional work rounds as usual and the three ward services implemented the CQI designed interdisciplinary work rounds." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The firm system randomization procedures and their validation have been reviewed extensively in the literature. Each inpatient firm has two physician teams or ward services. For this trial the six ward services were divided so that three ward services continued traditional work rounds as usual and the three ward services implemented the CQI designed interdisciplinary work rounds." |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Quote: "After controlling for baseline differences in case‐mix using a multivariate propensity score, the length of stay and total charges for the hospital stay for the patients included in the trial were evaluated." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Patient data were retrieved from the hospital’s administrative and billing system. Thus, patient specific cost and efficiency outcomes were limited to resource utilization in the form of hospital length of stay and total charges." "...the Respiratory Therapy (RT) Department conducted a study of aerosol use appropriateness, as determined by criteria previously devised and tested by the RT Department." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Practice level: Quote: "The outcome measures reported in this review were at the patient level. The study does report results from satisfaction surveys completed by 19 providers of the traditional rounds group and 21 providers of the interdisciplinary rounds group but provides no information about the total number of providers in each group." Patient level: Quote: "Study patients included all patients admitted to the medical inpatient units between November 8, 1993, and May 31, 1994, who spent at least 50% of their hospital stay on that unit and were discharged from that unit. If patients were readmitted during the trial, each admission was considered separately.” “Patient data were retrieved from the hospital’s administrative and billing system." |

| Contamination | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were excluded from analysis if their hospital stay was not on their assigned medical firm because they had been ’de‐firmed’ because of excess admissions to one service or if they were ’boarding’ on a floor that was not the ward team’s home floor. Patients were excluded from the trial if they were transferred from medicine to another service (e.g. surgery) or if less than 50% of their stay occurred on the medical floor..." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All relevant outcomes in the method section (AS6) were reported in the results section (AS7‐9). There was no published protocol so we cannot be sure all planned analyses were conducted. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected. |

| Methods | A post‐test‐only cluster‐RT of 30 teams caring for patients with COPD and PFF. 17 intervention teams and 13 control teams examined how the use of CPs improved teamwork in an acute hospital setting. | |

| Participants | Country: Belgium Doctors (i.e. orthopaedic surgeons or pneumologists), head nurses, nurses, and allied health professionals (i.e. physiotherapists and social workers). 581 participants: 346 in the intervention teams (N = 17) and 235 in the control teams (N = 13). | |

| Interventions | The intervention involved the development and implementation of CPs including 3 components: 1) feedback on team's performance before CP implementation; 2) receipt of evidence‐based key‐indicators for implementing CPs in practice to review; 3) training in CP development. Control teams: usual care. | |

| Outcomes | Conflict management, team climate for innovation, level of organised care, emotional exhaustion, level of competence, relational co‐ordination. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Stratified randomisation was used to assign the teams to an intervention group (using care pathways) and a control group (usual care). Interprofessional teams were randomised. COPD/PFF was used as blocking factor." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Before the start of the randomisation process, random numbers were assigned to each cluster by a researcher not involved in the study, using the online available tool 'Research Randomizer' www.randomizer.org). Next, the researcher randomly allocated the coded clusters to the intervention or control group using the same online tool." |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Intervention and control teams were reasonably similar. Quote: "No significant differences in organizational or team member characteristics were found, except for the number of years of experience, which was significantly higher in the control group" (Table 2). |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | High risk | It did not appear that there was any blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Practice level ITT was not mentioned. Authors acknowledged that sites dropped out. Quote: "A potential weakness of the study is the dropout of 7 teams and its possible impact on the results." |

| Contamination | Low risk | Only intervention teams participated in the development and implementation of CP. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the method section (p 100‐1) were reported in the results section (p 102‐4). There was also a published protocol and all planned analyses were conducted. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Cluster‐RT with appropriate statistical analysis. |

| Methods | A RT of 33 nursing homes, 15 experimental homes and 18 control homes, to examine the effects of monthly facilitated multidisciplinary rounds on the quality and quantity of psychotropic drug prescribing. | |

| Participants | Country: Sweden Physician, pharmacists, selected nurses, and nursing assistants. 1854 long‐term residents: 626 in experimental homes and 1228 in control homes. | |

| Interventions | Pharmacist led team meetings once a month over a period of 12 months. | |

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients receiving drugs, number of psychotropic drugs, use of non‐recommended hypnotics, use of non‐recommended anxiolytics, use of non‐recommended antidepressant drugs. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Thirty‐six nursing homes, representing 5% of all nursing homes in Sweden, participated in the study. The sampling process consisted of three steps. At the time of the study, the National Corporation of Swedish Pharmacies was organized into 36 regions, 18 of which were randomly selected for this study. Each regional pharmacy director then selected two facilities in his or her region using several criteria....Researchers randomly assigned one home in each pair to receive the intervention." |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "At baseline, we found no significant differences in the proportion of residents with scheduled psychotropics (64% vs 65%), number of drugs among residents with psychotropics (2.07 vs 2.06)." |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Quote: "There were no significant differences in the demographic, functional, or psychiatric characteristics of residents in experimental and control homes at baseline." Quote: "The overall level of prescribing was similar in experimental and control homes before the intervention (Table 2). At baseline, we found no significant differences in the proportion of residents with scheduled psychotropics (64% vs 65%), number of drugs among residents with psychotropics (2.07 vs 2.06), or proportion of residents with polymedicine (46% vs 47%). Baseline rates of therapeutic duplication were also comparable in the experimental and control homes." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Lists of each resident’s prescriptions were collected 1 month before and 1 month after the 12‐month intervention in both experimental homes and control homes. Trained coders, supervised by pharmacists, classified and coded all scheduled and PRN (pro re nata) orders." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | 3 intervention homes out of 18 became ineligible. |

| Contamination | Low risk | Quote: "Pharmacists assigned to experimental homes had no contact with control nursing homes. In the control homes, no efforts were made beyond normal routine to influence drug prescribing." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of high or low risk of bias. There was no published protocol so we cannot be sure all planned analyses were conducted. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected. |

| Methods | RT, in which patients with a stroke were treated by 31 teams from 31 Veteran Affair rehabilitation units before and after a multifaceted intervention, aimed at improving interprofessional collaboration. | |

| Participants | Country: USA Medical doctors, nurses, occupational therapists, speech‐language pathologists, physical therapists, and case managers or social workers. 464 participants: 227 in the intervention teams (N = 15) and 237 in the control teams (N = 16). Patients with a stroke were randomly assigned to each group. | |

| Interventions | Intervention teams: received the following multifaceted intervention: 1) an off‐site workshop emphasising team dynamics, problem‐solving, and the use of performance feedback data; 2) action plans (specific team performance profiles with recommendations) for process improvement; 3) telephone and video conference consultations to sustain improvement in collaboration. Control teams only received specific team performance profile Information. | |

| Outcomes | Functional improvement (as measured by the change in motor items of the FIM instrument), length of stay (LOS), rates of community discharge | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “... we randomized sites to either intervention or control group using a computer; each stratum was force randomized to have 4 sites in 1 arm.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of concealment was not described. |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | The mean FIM scores at baseline were similar for the intervention group (52.2 ± 3.9) and for the control group (52.4 ± 3.8). |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Quote: “…There were no differences between study conditions in demographic characteristics (table 2). Control sites admitted stroke patients with lower initial (admission) motor FIM scores during the pre‐intervention periods (P.002); thus, we adjusted all analyses using FRGs … a classification based on initial motor FIM and age.” |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | High risk | It did not appear that there was any blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | High risk | Acknowledged sites dropped out but ITT was not mentioned in the text Practice level Quote: “Of 33 eligible sites, a total of 31 sites agreed to participate, initiated the IRB approval, and were randomized. One control site was unable to complete the IRB process and withdrew, and 1 intervention site did not report data to the FSOD, leaving 15 sites in the control group and 14 in the intervention group. |

| Contamination | Low risk | No reason to think contamination had occurred. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All relevant outcomes in the methods section (p 11) were reported in the results section (p 14). There was a published protocol and all planned analyses were conducted. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected. |

| Methods | Randomised trial in which patients in inpatient telemetry ward in a community hospital were randomised to the intervention medical team, which conducted interdisciplinary rounds or to the control team, which provided standard care. | |

| Participants | Country: USA Resident physicians, nurses, a case manager, pharmacist, dietician, and physical therapist. Eighty‐four patients were enrolled: 42 in intervention and 42 in standard care. | |

| Interventions | Intervention: daily interdisciplinary rounds. Control group: standard care. | |

| Outcomes | Length of hospital stay | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was performed using random numerical assignments in pre‐sealed envelopes." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Envelope randomisation. |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Mean length of stay (days) was similar in the intervention group (3.04 ± 1.8) compared with the control group (2.7 ± 1.8). |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Quote: "There were no significant differences between groups for admission diagnosis; number of co‐morbidities; number of abnormal laboratory data; ability to perform activities of daily living; presence of dementia or diabetes, or whether there was a home health aide. In spite of randomization, the gender composition between groups was somewhat different...and the number of readmissions in the IR Team was higher than in the non‐IR Team (P = 0.003)." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Charts were surveyed to determine patient characteristics and LOS. LOS was measured as the difference between discharge and admission date." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Practice level: Quote: "Questionnaire return was 80%", but these results were not reported in this review because they did not meet outcome criteria. Patient level: All participants were accounted for and none were lost to follow‐up. |

| Contamination | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were randomly assigned to two medical teams: the intervention group received IRs and the control subjects received standard care." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All relevant outcomes in the method section (p 64) were reported in the results section (p 67). There was no published protocol so we cannot be sure all planned analyses were conducted. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected. |

| Methods | RT comparing multidisciplinary audio conferencing and multidisciplinary video conferencing with a team that worked at two hospitals. | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Medical staff specialists, medical registrars, nurses, speech pathologist, occupational therapists, social worker, medical students. Fifty patients were randomly assigned to each group. | |

| Interventions | Multidisciplinary audio conferences and video conferences. At each conference session, the audio conferences were conducted before the video conferences, with the same multidisciplinary team. | |

| Outcomes | Number of audio conferences held per patient, number of video conferences held, length of treatment. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The random allocation was done by an independent administrative assistant, using a table of random numbers." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The random allocation was done by an independent administrative assistant, using a table of random numbers." |

| Baseline outcome measurements similar ‐ All outcomes | Unclear risk | None reported. |

| Baseline characteristics similar | Low risk | Quote: "The two groups were similar in terms of age, sex and diagnosis (Table 1)." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) ‐ All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Conference times were recorded by an independent observer and files were reviewed by an independent medical practitioner blinded to the randomization." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) ‐ All outcomes | Unclear risk | Practice level: Quote: "Only 14 of 29 (including 6 medical students) completed a staff satisfaction survey. These results are not reported in this review because they did not meet outcome criteria." Patient level" Quote: "There were no deaths, and all patients recruited completed the trial." |

| Contamination | Unclear risk | Quote: "Within each meeting of the multidisciplinary team, the audioconferences were conducted before the videoconferences, to ensure that there was no visual contact between the two locations until the latter part of the session." "The team remained consistent at either site for both the audio‐ and videoconferences held on each individual day of the conference, but the team members rotated between sites over the study period." While measures were taken to prevent contamination, the same team members were involved in both types of conferencing. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All relevant outcomes in the method section (p 353‐4) were reported in the results section (p 354). Insufficient information was provided to permit judgement of high or low risk of bias. There was no published protocol so we cannot be sure all planned analyses were conducted. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected. |

CCTP = Chronic care team profile

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CP = care pathway

CQI = Continuous quality improvement

FIM = Functional independence measure

FRG = Functional‐related groups

FSOD = Functional status outcomes database

GP = General practitioner

IPC = Interprofessional collaboration

IRs = interdisciplinary rounds

IRB = Institutional Research Board

ITT = Intention‐to‐treat

KSA = Knowledge, skills, attitudes

LOS = length of stay

PACIC = Patient assessment of chronic illness care

PFF = proximal femur fracture

RT = randomised trial

WWT = Wider ward teams

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a RT | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a RT | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a RT | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a RT | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention | |

| Not a practice‐based IPC intervention |

IPC: interprofessional collaboration

RT: randomised trial

Flow diagram of study selection

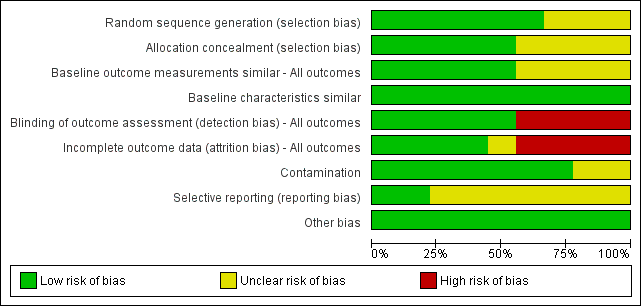

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies, based on EPOC methods.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study, based on EPOC methods.

| Effects of practice‐based interprofessional collaboration (IPC) interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes compared to usual care | |||

| Patient or population: health and social care professionals involved in the delivery of health services and patient care | |||

| Outcomes | Impacts | No. of studies (participants) | Certainty of the evidence |

| Patient health outcomes | |||

| Patient functional status | Externally facilitated interprofessional activities may slightly improve stroke patients' functional status (Strasser 2008). | 1 (464) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowa |

| Patient‐assessed quality of care | It is uncertain if externally facilitated interprofessional activities increases patient‐assessed quality of care because the certainty of this evidence is very low (Black 2013). | 1 (1185) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very lowb |

| Patient mortality, morbidity or complication rates | None of the included studies reported patient mortality, morbidity or complication rates. | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Clinical process or efficiency outcomes | |||

| Adherence to recommended practices | The use of interprofessional activities with an external facilitator or interprofessional meetings may slightly improve adherence to recommended practices and prescription of drugs (Cheater 2005; Deneckere 2013; Schmidt 1998). | 3 (2576) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowc |

| Continuity of care | It is uncertain if externally facilitated interprofessional activities improves continuity of care because the certainty of this evidence is very low (Strasser 2008). | 1 (464) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very lowd |

| dUse of healthcare resources | Interprofessional checklists (Calland 2011), interprofessional rounds (Curley 1998; Wild 2004) or externally facilitated interprofessional activities (Strasser 2008), may slightly improve overall use of resources, length of hospital stay, or costs. | 4 (1679) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowe |

| Collaborative behaviour outcomes | |||

| Collaborative working; team communication; team co‐ordination | It is uncertain whether externally facilitated interprofessional activities (Black 2013; Calland 2011; Cheater 2005; Deneckere 2013) improve collaborative working, team communication, and co‐ordination because the certainty of this evidence is very low. | 4 (1936) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ Very lowf |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||

| a We assessed the certainty of the evidence as low because of high risk of bias (no blinding of outcome assessment). b We assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low because of the risk of bias (high risk of attrition and detection bias; details about allocation sequence generation and concealment were not reported). c We assessed the certainty of the evidence as low due to potential indirectness (both studies were conducted in one country and the outcomes may not be transferable to other settings), and risk of bias (high risk of attrition, unclear selection and reporting risk). d We assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low because of risk of bias (high risk of attrition and detection bias, and unclear risk of selection bias). e We assessed the certainty of evidence as low because of high risk of bias (attrition and detection), and unclear risk of bias (selection, reporting, and contamination). f We assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low due to high risk of bias (selection, attrition, and detection) or unclear risk of bias (reporting and contamination). | |||

| Effects of practice‐based interprofessional collaboration (IPC) interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes compared with alternative IPC intervention | |||

| Patient or population: health and social care professionals involved in the delivery of health services and patient care Settings: two hospitals in Australia Intervention: multidisciplinary video conferencing Comparison: multidisciplinary audio conferencing | |||

| Outcomes | Impacts | No. of | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Patient health outcomes | The study did not report patient health outcomes. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Clinical process or efficiency outcomes | Video conferencing may reduce the average length of treatment, compared to audio conferencing and may improve process/efficiency outcomes by reducing the number of multidisciplinary conferences needed per patient and patient length of stay. | 1 (100) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowa |

| Collaborative behaviour outcomes | There was little or no difference between the interventions in the number of communications between health professionals. | 1 (100) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Lowa |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||

| a We assessed the certainty of evidence as low because of high risk of bias (attrition and detection) and unclear risk of bias (selection, reporting, and contamination). | |||