Secuenciación de antraciclinas y taxanos en el tratamiento neoadyuvante y adyuvante para el cáncer de mama en estadio inicial

Resumen

Antecedentes

Las antraciclinas y los taxanos son agentes quimioterapéuticos ampliamente usados en un régimen secuencial en el tratamiento coadyuvante y neoadyuvante del cáncer de mama en estadio inicial para reducir el riesgo de recidiva del cáncer. La práctica estándar es administrar quimioterapia basada en antraciclina seguida de un taxano. Las antraciclinas tienden a ser administradas en primer lugar debido a que se establecieron antes de los taxanos para el tratamiento del cáncer de mama en estadio inicial.

Objetivos

Evaluar si la secuencia en que se administran las antraciclinas y los taxanos afecta los resultados para las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial que reciben tratamiento adyuvante o neoadyuvante.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se hicieron búsquedas en el registro especializado del Grupo Cochane de Cáncer de Mama (Cochrane Breast Cancer's Specialised Register), CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, en la World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) y en ClinicalTrials.gov el 1 febrero 2018.

Criterios de selección

Ensayos controlados aleatorios que comparan la administración de un taxano antes de una antraciclina con taxano luego de la antraciclina en pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial que reciben quimioterapia. Los estudios debían haber informado de al menos uno de los resultados de interés, que incluían la supervivencia general, la supervivencia libre de enfermedad, la respuesta patológica, la adherencia al tratamiento, la toxicidad y la calidad de vida.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Dos autores de la revisión extrajeron los datos de forma independiente, evaluaron el riesgo de sesgo y la calidad de la evidencia. La medida de resultado primaria fue la supervivencia general. Los resultados secundarios incluyeron la supervivencia libre de enfermedad, la respuesta patológica (en el contexto neoadyuvante solamente), los eventos adversos, la adherencia al tratamiento y la calidad de vida. Para los resultados del tiempo hasta el evento de la supervivencia general y la supervivencia libre de enfermedad, se derivaron los cocientes de riesgos instantáneos (CRI) con intervalos de confianza (IC) del 95% cuando fue posible. Para los resultados dicótomos de la respuesta patológica completa, la adherencia al tratamiento y los eventos adversos, se informó sobre el efecto del tratamiento como un cociente de riesgos (CR) con IC del 95% cuando fue posible. Se utilizó GRADE para evaluar la certeza de la evidencia por separado para el contexto neoadyuvante y coadyuvante.

Resultados principales

Hubo 1415 participantes en cinco estudios de la quimioterapia neoadyuvante y 280 participantes en cuatro estudios de la quimioterapia coadyuvante que incluyeron cinco comparaciones de tratamientos. Cuatro de los cinco estudios de la quimioterapia neoadyuvante recopilaron datos para el resultado primario (supervivencia general) y dos estudios tuvieron datos disponibles; uno de los cuatro estudios de la quimioterapia coadyuvante recopiló los datos de la supervivencia general.

Los estudios de la quimioterapia neoadyuvante indicaron que la administración de taxanos en primer lugar probablemente dio lugar a poca a ninguna diferencia en la supervivencia general (CRI 0,80; IC de 95%: 0,60 a 1,08; 947 participantes; dos estudios; evidencia de certeza moderada) y la supervivencia libre de enfermedad (CRI 0,84; IC del 95%: 0,65 a 1,09; 828 participantes; un estudio; evidencia de certeza moderada). La administración de taxanos en primer lugar también dio lugar a poca a ninguna diferencia en la respuesta patológica completa (ausencia de cáncer en la mama y la axila: CR 1,15; IC del 95%: 0,96 a 1,38; 1280 participantes; cuatro estudios; evidencia de certeza alta). Sin embargo, pareció haber una tendencia a favor de los taxanos en primer lugar. Los estudios informaron sobre la adherencia al tratamiento mediante un rango de medidas. La administración de taxanos en primer lugar probablemente no aumentó la probabilidad de requerir reducciones de la dosis en comparación con la administración de antraciclinas primero (CR 0,81; IC de 95%: 0,59 a 1,11; 280 participantes; un estudio; evidencia de certeza moderada). Probablemente hubo poca a ninguna diferencia en el riesgo de neutropenia de grado 3/4 (CR 1,25; IC de 95%: 0,86 a 1,82; 280 participantes, un estudio; evidencia de certeza moderada) o neurotoxicidad de grado 3/4 (CR 0,95; IC de 95%: 0,55 a 1,65; 1108 participantes; dos estudios; evidencia de certeza baja) cuando los taxanos se administraron en primer lugar. No había datos sobre la calidad de vida.

Sólo un estudio de la quimioterapia coadyuvante recopiló datos sobre la supervivencia general y la supervivencia libre de enfermedad aunque no informó los datos. La administración de taxanos en primer lugar redujo el riesgo de neutropenia de grado 3/4 (CR 0,62; IC de 95%: 0,40 a 0,97; 279 participantes; cuatro estudios, cinco comparaciones de tratamientos; evidencia de certeza alta) y pareció dar lugar a poca a ninguna diferencia en la neurotoxicidad de grado 3/4 (CR 0,78; IC de 95%: 0,25 a 2,46; 162 participantes; tres estudios; evidencia de baja certeza). Probablemente hubo poca a ninguna diferencia en las proporciones que sufrieron retrasos en la dosis cuando los taxanos se administraron primero en comparación con las antraciclinas administradas primero (CR 0,76; IC de 95%: 0,52 a 1,12; 238 participantes; tres estudios, cuatro comparaciones de tratamientos; evidencia de certeza moderada). Un estudio informó sobre la calidad de vida e indicó que las puntuaciones (mediante el cuestionario validado Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast Cancer [FACT‐B]) fueron similares en ambos grupos aunque no proporcionó datos numéricos.

Conclusiones de los autores

En el contexto neoadyuvante, hay evidencia de certeza alta a baja de resultados equivalentes para la secuencia en la cual se administran los taxanos. En el contexto coadyuvante, ninguno de los estudios informó sobre la supervivencia general o la supervivencia libre de enfermedad. En la mayoría de las instituciones, la práctica estándar sería la administración de antraciclina seguida de taxano y los datos disponibles en la actualidad no apoyan un cambio en esta práctica. Se espera la publicación de texto completo de un estudio de la quimioterapia neoadyuvante relevante para las pacientes con cáncer de mama negativo para el HER2 para la inclusión en una actualización de esta revisión.

PICOs

Resumen en términos sencillos

Quimioterapia con taxanos antes o después de la quimioterapia con antraciclina en el cáncer de mama en estadio inicial

Las antraciclinas y los taxanos son clases activas de agentes quimioterapéuticos que se utilizan antes o después de la cirugía por cáncer de mama en estadio inicial.

¿Cuál es el objetivo de esta revisión?

Se procuró determinar si la administración de quimioterapia con taxanos antes de la quimioterapia con antraciclina (en vez de después) a las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial (cuando el cáncer no se ha difundido más allá de los ganglios linfáticos cercanos a la mama) cambiaría los resultados.

Aunque los beneficios del agregado de taxanos a las antraciclinas están bien establecidos, no se conoce si la administración de quimioterapia con taxanos antes o después de la quimioterapia con antraciclina tiene una repercusión sobre la duración de la vida de la paciente, por cuánto tiempo permanece libre de cáncer de mama, la finalización del tratamiento, los efectos secundarios del tratamiento y la calidad de vida.

Mensajes clave de la revisión

El orden en el cual se administran las quimioterapias con taxano y antraciclina puede haber tenido poca o ninguna repercusión sobre:

– la duración de la vida de las participantes;

– por cuánto tiempo permanecieron libres de cáncer de mama;

– la finalización del tratamiento y

– efectos secundarios del tratamiento.

Ninguno de los estudios informó datos sobre la calidad de vida. Muchos de los estudios no revelaron información sobre los resultados importantes como por cuánto tiempo vivirán las pacientes o permanecerán libres de cáncer de mama. Se aguarda la publicación de un estudio relevante que incluye a 112 participantes que reciben quimioterapia antes de la cirugía para el cáncer de mama para la inclusión en una actualización de esta revisión.

En resumen, los resultados no encontraron evidencia suficiente de un efecto beneficioso o perjudicial debido al orden en el cual se administran las quimioterapias con taxano y antraciclina. En la mayoría de las instituciones, la práctica estándar sería la administración de antraciclina seguida de taxano. Basado en esta revisión de la evidencia, los datos disponibles en la actualidad no apoyan un cambio en esta práctica.

¿Qué se estudió en la revisión?

Para las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial que tienen un riesgo mayor de recidiva del cáncer, a menudo se ofrece la quimioterapia combinada con antraciclina y taxano antes o después de la cirugía para reducir el riesgo de recidiva del cáncer y prolongar la vida. Tradicionalmente, las antraciclinas se administran primero seguidas de los taxanos aunque no hay evidencia sólida en cuanto a este orden. Se comparó la posibilidad de administrar los taxanos en primer lugar seguidos de las antraciclinas en comparación con el tratamiento estándar con antraciclina en primer lugar.

¿Cuáles son los principales resultados de la revisión?

Todos los participantes en los estudios fueron mujeres. Se encontraron cinco estudios que incluían a 1415 participantes en los cuales la quimioterapia se había administrado antes de la cirugía. El taxano utilizado en tres de estos estudios fue paclitaxel, mientras que los otros dos estudios usaron docetaxel. Dos estudios usaron un único agente de antraciclina (epirubicina), mientras que tres estudios usaron una combinación de epirubicina, ciclofosfamida y fluorouracilo. También hubo cuatro estudios que incluían a 280 participantes y que comparaban el orden de la administración de taxanos y antraciclinas en participantes que estaban recibiendo quimioterapia después de la cirugía por cáncer de mama. El taxano usado en los cuatro estudios fue docetaxel, mientras que las antraciclinas usadas fueron una combinación de epirubicina o adriamicina más ciclofosfamida o fluorouracilo (o ambos).

Los resultados principales fueron que el orden en el cual se administra la quimioterapia con taxanos:

–probablemente dio lugar a poca a ninguna diferencia en la supervivencia o el riesgo de recidiva del cáncer para las participantes que reciben quimioterapia antes de la cirugía;

–probablemente dio lugar a poca o ninguna diferencia en el grado en el que el tumor puede haberse reducido en respuesta a la quimioterapia para las participantes que recibieron quimioterapia antes de la cirugía;

–puede haber dado lugar a poca o ninguna diferencia en cuanto a los efectos secundarios para las participantes que recibieron quimioterapia antes de la cirugía aunque la administración de taxanos en primer lugar redujo el riesgo de neutropenia (recuento bajo de leucocitos) en las que recibieron quimioterapia después de la cirugía. Los efectos secundarios que se examinaron fueron la neutropenia y la neurotoxicidad (daño a los nervios);

–probablemente dio lugar a poca a ninguna diferencia en la proporción de participantes que recibieron quimioterapia después de la cirugía por cáncer de mama que experimentaron retrasos en las dosis de quimioterapia.

Muchos estudios no recopilaron ni informaron los datos sobre la supervivencia, el riesgo de recidiva del cáncer o el bienestar general (calidad de vida). En algunos casos, los estudios no informaron datos que podrían usarse en la revisión y se esperan las respuestas de los investigadores que realizaron los ensayos.

¿Cuál es el grado de actualización de esta revisión?

Los autores de la revisión buscaron estudios que se habían publicado hasta febrero 2018.

Conclusiones de los autores

Summary of findings

| Taxane followed by anthracyclines compared to anthracyclines followed by taxane in neoadjuvant therapy for early breast cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: neoadjuvant therapy for early breast cancer | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with anthracyclines followed by taxane | Risk with taxane followed by anthracyclines | |||||

| Overall survival | 3‐year risk of deatha | HR 0.80 | 947 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | — | |

| 702 per 1000 | 620 per 1000 | |||||

| Disease‐free survival | 3‐year risk of recurrencea | HR 0.84 | 828 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | — | |

| 616 per 1000 | 552 per 1000 | |||||

| Pathological complete response (no invasive cancer in breast or axilla) (follow‐up: up to 5 years for 2 studies; unreported in 2 studies) | Study population | RR 1.15 | 1280 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | — | |

| 228 per 1000 | 262 per 1000 | |||||

| Adverse events: neutropenia (grade 3/4) (follow‐up: up to 6 months based on number of chemotherapy cycles) | Study population | RR 1.25 | 280 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | — | |

| 254 per 1000 | 317 per 1000 | |||||

| Adverse events: neurotoxicity (grade 3/4) (follow‐up: up to 5 or 6 months based on number of chemotherapy cycles) | Study population | RR 0.95 | 1108 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | — | |

| 45 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 | |||||

| Treatment adherence (defined as dose reduction) (follow‐up: up to 6 months based on number of chemotherapy cycles) | Study population | RR 0.81 | 280 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | — | |

| 399 per 1000 | 323 per 1000 | |||||

| Quality of life | — | — | — | — | Not measured | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| aThe baseline risk in the anthracycline followed by taxane group was based on risk estimates provided in Neo‐TAnGo 2014 (Figure 2D for overall survival; Figure 2B for disease‐free survival). | ||||||

| Taxane followed by anthracyclines compared to anthracyclines followed by taxane in adjuvant therapy for early breast cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: adjuvant therapy for early breast cancer | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with anthracyclines followed by taxane | Risk with taxane followed by anthracyclines | |||||

| Overall survival | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Disease‐free survival | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Adverse events: neutropenia (grade 3/4) (follow‐up: up to 3.5 or 4.5 months) | Study population | RR 0.62 | 279 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | — | |

| 255 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 | |||||

| Adverse events: neurotoxicity (grade 3/4) (follow‐up: up to 4 or 4.5 months) | Study population | RR 0.78 | 162 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | — | |

| 63 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 | |||||

| Treatment adherence (defined as dose delay) (follow‐up: up to 3.5 or 4.5 months) | Study population | RR 0.76 | 238 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | — | |

| 333 per 1000 | 253 per 1000 | |||||

| Quality of life (follow‐up: up to 4 months) | 1 study reported quality of life data using the FACT‐B version 4 questionnaire (Puhalla 2008). Scores were similar in both groups for a subset of 20 participants who were assessed before, during and after treatment. Numerical or further details were not provided in the trial publication. | — | 20 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | — | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| aWe did not downgrade the certainty of the evidence. A lack of blinding was judged to be unlikely to influence physician assessment of grade 3/4 neutropenia (blood tests) and there was no heterogeneity detected across studies. | ||||||

Antecedentes

Descripción de la afección

El cáncer de mama es la neoplasia maligna más común y la segunda causa principal de mortalidad relacionada con el cáncer entre las mujeres en todo el mundo, por lo tanto, representa una carga significativa de asistencia sanitaria (Ferlay 2015). Durante los últimos decenios ha habido mejorías sustanciales en la supervivencia para las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial después de la introducción de la quimioterapia coadyuvante (después de la cirugía) y neoadyuvante (antes de la cirugía), la terapia endocrina y terapia dirigida por el receptor del factor de crecimiento epidérmico humano 2 (HER2) (Cossetti 2015).

Descripción de la intervención

Las antraciclinas y los taxanos son clases activas de agentes quimioterapéuticos usadas en el tratamiento coadyuvante y neoadyuvante de las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial.

Las antraciclinas (por ejemplo, doxorrubicina, epirubicina, doxorrubicina liposomal) ejercen su efecto al complejizarse con el ADN y la topoisomerasa II para inducir la apoptosis (es decir la muerte de las células) e inhibir la síntesis de ADN y de ácido ribonucleico (ARN). Las posibles toxicidades de las antraciclinas incluyen cardiotoxicidad, mielosupresión (que da lugar a un número reducido de glóbulos) y neoplasias malignas secundarias (predominantemente tipos de cáncer hematológico).

Los taxanos (por ejemplo docetaxel, paclitaxel, nab‐paclitaxel) ejercen su efecto al estabilizar los microtúbulos (ejes fibrosos que ayudan a los cromosomas a dividirse) y de ese modo inhiben la división celular y la función celular. Las toxicidades potenciales de los taxanos incluyen neuropatía (es decir cosquilleo en las manos y pies), mielosupresión y mialgia (dolor muscular).

Actualmente, la práctica clínica estándar para las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial incluye la administración de un régimen de quimioterapia basada en antraciclina seguido de un taxano. La razón de esta secuencia establecida parece ser histórica en lugar de vinculada a los resultados. Las antraciclinas se desarrollaron primero y el beneficio de la quimioterapia con antraciclina para el cáncer de mama en estadio inicial se estableció antes del de los taxanos (Jones 2006; Levine 1998). Sin embargo, una razón para evaluar la secuencia óptima de las antraciclinas y los taxanos es el hallazgo de que los resultados fueron mejores cuando los taxanos se administraban primero, en un análisis retrospectivo amplio que incluyó a aproximadamente 1600 pacientes con cáncer de mama que recibieron paclitaxel y antraciclina como tratamiento coadyuvante (Alvarez 2010).

De qué manera podría funcionar la intervención

No se conoce si el orden en el cual son administrados los taxanos y las antraciclinas da lugar a resultados significativamente diferentes para las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial. Aún debe determinarse si la administración de taxanos en primer lugar da lugar a resultados mejores, peores o a ninguna diferencia en los resultados del tratamiento. El efecto también puede diferir según el estado del receptor del tumor.

Por qué es importante realizar esta revisión

El objetivo de esta revisión fue evaluar si la secuencia en la cual se administran las antraciclinas y los taxanos, como quimioterapia coadyuvante o neoadyuvante, afecta los resultados para las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial. Los resultados de esta revisión podrían guiar potencialmente el manejo de la secuenciación de la quimioterapia para las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial que requieren quimioterapia coadyuvante o neoadyuvante. Una revisión sistemática anterior examinó este tema importante, aunque desde su publicación se han realizado más ensayos (Bines 2014). Esta revisión Cochrane complementa la revisión de Bines 2014 al agregar los resultados de ensayos más recientes y evaluar de forma crítica los estudios incluidos.

Objetivos

Evaluar si la secuencia en que se administran las antraciclinas y los taxanos afecta los resultados para las pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial que reciben tratamiento adyuvante o neoadyuvante.

Métodos

Criterios de inclusión de estudios para esta revisión

Tipos de estudios

Todos los ensayos controlados aleatorios (ECA) que examinaban la secuencia de la administración de las antraciclinas y los taxanos en pacientes con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial que recibían quimioterapia coadyuvante o neoadyuvante.

Tipos de participantes

A partir de los 18 años de edad, con cáncer de mama en estadio inicial apropiado para la quimioterapia coadyuvante o neoadyuvante.

Tipos de intervenciones

Intervención

Quimioterapia con taxanos (docetaxel, paclitaxel o nab‐paclitaxel) administrada antes de la quimioterapia basada en antraciclina. El mismo régimen de fármacos fue administrado como el brazo comparador en la secuencia inversa. Se incluyeron estudios en los cuales se administraron intervenciones concurrentes con otra quimioterapia no basada en antraciclina, factor estimulante de colonias de granulocitos o trastuzumab. Se excluyeron los estudios en que se administraron intervenciones concomitantes con radioterapia o terapia endocrina. Las intervenciones podrían incluir:

-

docetaxel administrado por vía intravenosa en cualquier dosis una vez por semana, cada 14 días o cada 21 días durante tres o cuatro ciclos;

-

paclitaxel administrado por vía intravenosa en cualquier dosis una vez por semana durante 12 semanas, cada 14 días o 21 días durante tres o cuatro ciclos;

-

nab‐paclitaxel administrado por vía intravenosa en cualquier dosis una vez por semana o cada 21 días durante tres o cuatro ciclos.

Comparador

Quimioterapia basada en antraciclina (doxorrubicina, epirubicina o doxorrubicina liposomal) administrada antes de la quimioterapia con taxano. El mismo régimen de fármacos fue administrado como en el brazo de intervención aunque en la secuencia inversa. Se incluyeron estudios en los cuales se administraron intervenciones concurrentes con cualquier quimioterapia sin taxano o factor estimulante de colonias de granulocitos o trastuzumab. Se excluyeron los estudios en que se administraron intervenciones concomitantes con radioterapia o terapia endocrina. Las comparaciones podían incluir:

-

doxorrubicina administrada por vía intravenosa en cualquier dosis cada 14 días o cada 21 días durante tres o cuatro ciclos;

-

epirubicina administrada por vía intravenosa en cualquier dosis cada 14 días o cada 21 días durante tres o cuatro ciclos;

-

doxorrubicina liposomal administrada en cualquier dosis o frecuencia durante tres o cuatro ciclos.

Tipos de medida de resultado

Resultados primarios

Contexto neoadyuvante y coadyuvante

-

Supervivencia general, definida como el tiempo desde la asignación al azar/incorporación al estudio hasta la muerte por cualquier causa.

Resultados secundarios

Contexto neoadyuvante

-

Supervivencia libre de enfermedad, definida como el tiempo desde la cirugía hasta la primera recidiva del cáncer de mama en cualquier sitio, la aparición de un nuevo cáncer de mama ipsilateral (misma mama que el cáncer de mama anterior) o contralateral (diferente mama que el cáncer de mama anterior) o enfermedad maligna secundaria diferente al cáncer de mama con la excepción del carcinoma escamocelular o de células basales de la piel, el cáncer hematológico o el carcinoma in situ del cuello uterino.

-

Respuesta patológica completa (RPC), definida como ningún carcinoma invasivo en los ganglios linfáticos de la mama o la axila (ypT0/isypN0 [estadiaje del TNM; AJCC 2010]) después de la terapia neoadyuvante.

-

Puntuación Standardised Residual Cancer Burden (RCB; MD Anderson Cancer Center).

-

Grado de respuesta después de la terapia neoadyuvante:

-

-

ningún carcinoma invasivo o in situ en los ganglios linfáticos de la mama o la axila (ypT0ypN0);

-

ningún carcinoma invasivo en la mama (ypT0/isypN0/+);

-

ningún carcinoma invasivo en los ganglios linfáticos axilares (ypN0).

-

Contexto coadyuvante

-

Supervivencia libre de enfermedad, definida como el tiempo desde la asignación al azar hasta la primera recidiva del cáncer de mama en cualquier sitio, la aparición de nuevo cáncer de mama ipsilateral o contralateral o una enfermedad maligna secundaria diferente al cáncer de mama con la excepción del carcinoma escamocelular o de células basales de la piel, el cáncer hematológico o el carcinoma in situ del cuello uterino.

Contexto neoadyuvante y coadyuvante

-

Eventos adversos clasificados según la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) o los National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI‐CTCAE):

-

-

neutropenia febril;

-

neutropenia;

-

toxicidad cardíaca;

-

toxicidad pulmonar;

-

neurotoxicidad;

-

neoplasia maligna hematológica;

-

muerte relacionada con el tratamiento.

-

-

Adherencia al tratamiento, definida como retraso en el tratamiento o reducciones de la dosis, o ambos, o la cesación temprana del tratamiento.

-

Calidad de vida medida mediante un instrumento validado.

Ver resultados principales en la tabla de “Resumen de resultados” para obtener el resumen de la evidencia

Los siguientes resultados se incluyeron en una tabla de “Resumen de resultados” mediante el enfoque GRADE (Schünemann 2011).

-

Supervivencia general (mortalidad).

-

Supervivencia libre de enfermedad (recidiva).

-

RPC para el contexto neoadyuvante.

-

Adherencia al tratamiento.

-

Eventos adversos incluida la neutropenia y la neurotoxicidad de grado 3/4.

-

Calidad de vida.

Métodos de búsqueda para la identificación de los estudios

Búsquedas electrónicas

We searched the following databases on 1 February 2018.

-

The Cochrane Breast Cancer's Specialised Register. Details of the search strategies used by the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group (CBCG) for the identification of studies and the procedure used to code references are outlined on the Group's website (Cochrane Breast Cancer Group’s Specialised Register). We extracted and considered for inclusion in the review trials with the key words "breast neoplasm; breast cancer; breast carcinoma; breast adenocarcinoma; breast tumour/tumor; adjuvant; neoadjuvant; anthracycline; taxane; chemotherapy; docetaxel; paclitaxel; nab‐paclitaxel; cabazitaxel; doxorubicin; epirubicin; daunorubicin; idarubicin and valrubicin".

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 1, 2018; in the Cochrane Library; Appendix 1).

-

MEDLINE OvidSP (top up search to complement CBCG's Specialised Register; Appendix 2).

-

Embase OvidSP (from 1974; Appendix 3).

-

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal for all prospectively registered and ongoing trials (apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx; Appendix 4).

-

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/; Appendix 5).

Búsqueda de otros recursos

-

Bibliographic searching.

We tried to identify further studies from the reference lists of identified relevant trials or reviews. We obtained a copy of the full article for each reference reporting a potentially eligible trial. Where this was not possible, we contacted authors to obtain additional information (as outlined in the 'Notes' section in the Characteristics of included studies table).

-

Searching conference proceedings.

We searched the following conference proceedings in Embase (via OvidSP) from 2006 to 1 February 2018 to identify relevant abstracts:

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Scientific Meeting;

-

European Society for Medical Oncology Annual Scientific Meeting;

-

San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium;

-

American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Symposium;

-

European Breast Cancer Conference.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Selección de los estudios

We merged the search results using reference management software (e.g. Endnote) and uploaded the records into Covidence (Covidence). Two review authors (MZ and AG) independently screened titles and abstracts, and assessed full‐text articles for potentially relevant studies for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement about the eligibility of a study by discussion and, if required, by consulting a third review author (NW). We recorded our reasons for the exclusion of any potentially relevant studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We imposed no language restrictions. If required for future review updates, we will obtain translations of relevant studies. We recorded the selection process in a PRISMA flow diagram.

Extracción y manejo de los datos

Two review authors (MZ and MW) independently extracted data using standard extraction forms tested and refined for this review. We collected the following information: study design, participants, setting, interventions, follow‐up, sources of funding, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors and outcomes.

We extracted at least the following items.

-

General information: title, authors, contact details, location, publication status, language, year of publication, source of funding.

-

Trial characteristics: study design, length of follow‐up.

-

Participants: inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, baseline characteristics and similarity at baseline, neoadjuvant/adjuvant setting, hormone receptor status, HER2 in‐situ hybridisation status, withdrawals, losses to follow‐up.

-

Intervention and comparator: drug, dose, timing and number of cycles, dose reductions, dose omissions.

-

Adverse events and toxicities.

-

Outcomes: hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), log rank Chi² statistic, P values from log‐rank test, number of events.

We resolved any disagreement regarding the extraction of quantitative data by discussion and, if required, by consulting a third review author (NW, AG or DO'C). For studies with more than one publication, we collated data from each publication into a single data collection form and considered the final or updated version of each study the primary reference.

Evaluación del riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos

Two review authors (MZ and MW) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' assessment tool, as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Chapter 8.5; Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion and, if needed, by consulting a third author (AG, NW or DO'C). We assessed the following sources of bias:

-

sequence generation;

-

allocation concealment;

-

blinding of participants, personnel;

-

blinding of outcome assessment for outcomes other than overall survival;

-

incomplete outcome data;

-

selective outcome reporting;

-

other sources of bias.

We described the 'Risk of bias' assessments in a 'Risk of bias' table (see Characteristics of included studies table).

Medidas del efecto del tratamiento

For dichotomous outcomes (i.e. a variable with only two outcomes such as yes or no) – treatment adherence (i.e. dose delays, dose reductions, one‐dose reduction, did not receive planned number of cycles), pCR and adverse events – we reported the treatment effect as a risk ratio (RR) and 95% CI. We planned to report the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome if there was a significant difference in pCR. RRs less than 1.0 favour the administration of taxanes first for adverse outcomes (i.e. lack of treatment adherence, adverse events) or favour administration of anthracyclines first for beneficial outcomes (i.e. pCR). The reverse is the case for RRs greater than 1.0.

In review updates, for continuous outcomes (where measurement is continuous on a numerical scale) – quality of life – we will report the treatment effect as a standardised mean difference and 95% CI as quality of life is expected to be measured using different scales. If all studies use the same scale, we will report the mean difference. In the current review, only one study measured quality of life but did not report any numerical data. There was a second continuous outcome reported, mean dose intensity for treatment adherence, but a measure of variation was not reported for this outcome. Therefore, the data could not be pooled in a meta‐analysis and are presented in a separate table for completeness (see Table 1 and Table 2).

For time‐to‐event outcomes – disease‐free survival and overall survival – we reported the treatment effect as a HR and 95% CI. For those studies that reported overall survival or disease‐free survival data, we extracted the HR and associated variances directly from the trial publications. In review updates, if this is not possible, we will obtain the data indirectly, using methods described by Parmar 1998 or Tierney 2007. We will record the use of indirect methods in the Notes section of the Characteristics of included studies table. We reported the ratios of treatment effects for response so that HRs less than 1.0 favoured the administration of taxanes first and HRs greater than 1.0 favoured the administration of anthracyclines first.

Cuestiones relativas a la unidad de análisis

In the neoadjuvant setting, Neo‐TAnGo 2014 was a four‐arm study that randomised women to anthracycline then paclitaxel or reverse order with or without gemcitabine. For the purpose of this review, we combined the two intervention arms (taxane followed by anthracycline with or without gemcitabine) and the two comparison arms (anthracycline followed by taxane with or without gemcitabine).

In the adjuvant setting, AERO B03 2007 was a three‐arm study and we only included the data relating to treatments with both a taxane and anthracycline. The Wildiers study was a four‐arm study that randomised women to either conventional chemotherapy (taxane followed by anthracycline or in reverse order) or dose‐dense treatment (taxane followed by anthracycline or in reverse order). We used data from all four treatments arms and split them into two treatment comparisons: Wildiers 2009a and Wildiers 2009b.

Manejo de los datos faltantes

We contacted authors of some included studies in writing to request missing data (e.g. overall survival, disease‐free survival and relative dose intensity outcome data) (Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Alamgeer 2014; Puhalla 2008).

Evaluación de la heterogeneidad

We assessed the degree of heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots, the I² statistic (Higgins 2003), and the Chi² test for heterogeneity (Cochran 1954). We considered there to be substantial statistical heterogeneity if the I² statistic was greater than 50% and the P value was less than 0.10 for the Chi² test for heterogeneity. For this initial review, as the expected number of included trials was small and, therefore, we did not expect significant heterogeneity, we used the fixed‐effect model. In review updates, we plan to use the random‐effects model (see Data synthesis) for pooling estimates across trials unless the results are affected by the inclusion of small studies. If this occurs, then we will also use the fixed‐effect model and compare the results.

Evaluación de los sesgos de notificación

As the review included fewer than 10 studies, we did not formally assess publication bias using funnel plots. If additional studies are available in review updates, we will assess publication or other bias by visual examination of funnel plot symmetry provided there are at least 10 studies in the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2011). Where possible, we will review the protocols of included studies to assess outcome reporting bias.

Síntesis de los datos

We pooled data using the fixed‐effect model as sufficiently similar (in terms of population and intervention) studies were available to provide meaningful results in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings. We performed all analyses using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014).

For dichotomous outcomes, we used the fixed‐effect method (Mantel‐Haenszel; Mantel 1959). In review updates, we will use the random‐effects method (DerSimonian 1986).

Data could not be pooled for continuous outcomes in this review. However, in review updates, for continuous outcomes, we will use the random‐effects with inverse variance method (Deeks 2011).

For time‐to‐event outcomes, we used the fixed‐effect with inverse variance method. In review updates, we will use the random‐effects (DerSimonian and Laird with inverse‐variance) method.

In review updates, if we are concerned about the effect of small studies on the random‐effects meta‐analysis, we will compare the fixed‐effect and random‐effects estimates. If results from the fixed‐effect and random‐effects analysis are different, we will perform sensitivity analyses to consider restricting the meta‐analysis to include the larger studies only.

'Summary of findings' table

Two review authors (MZ and MW) used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence for the following outcomes: overall survival (event: risk of death), disease‐free survival (event: risk of recurrence), pCR, treatment adherence, adverse events and quality of life. We used GRADEpro GDT software to develop the 'Summary of findings' tables and followed GRADE guidance (Schünemann 2011).

To calculate the absolute risk for the control group for time‐to‐event outcomes, we derived the event rate at a specific time point (three‐year risk for both overall survival and disease‐free survival) from the Kaplan‐Meier curve in the Neo‐TAnGo 2014 study; only the neoadjuvant studies reported data for overall survival and disease‐free survival. We entered the event rate at three years and the pooled HR into GRADEpro GDT and estimated the corresponding absolute risk for the intervention group at three years by the GRADEpro GDT software.

Análisis de subgrupos e investigación de la heterogeneidad

We presented data separately for participants receiving neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy. We presented data from one or two trials separately for the following prespecified patient subgroups:

-

people with positive versus negative HER2 status;

-

people with positive, negative or triple negative hormone receptor status.

In review updates, we will conduct tests for interaction to determine whether the sequence in which anthracyclines and taxanes are administered has a significantly different effect in subgroups.

Análisis de sensibilidad

Due to the limited data available, the proposed sensitivity analysis was not undertaken. In review updates, we plan to perform the following sensitivity analysis:

-

risk of bias: low versus high/unclear risk of bias. We will assign an overall unclear/high risk of bias to studies in which we have judged at least four of the seven domains to have unclear/high risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

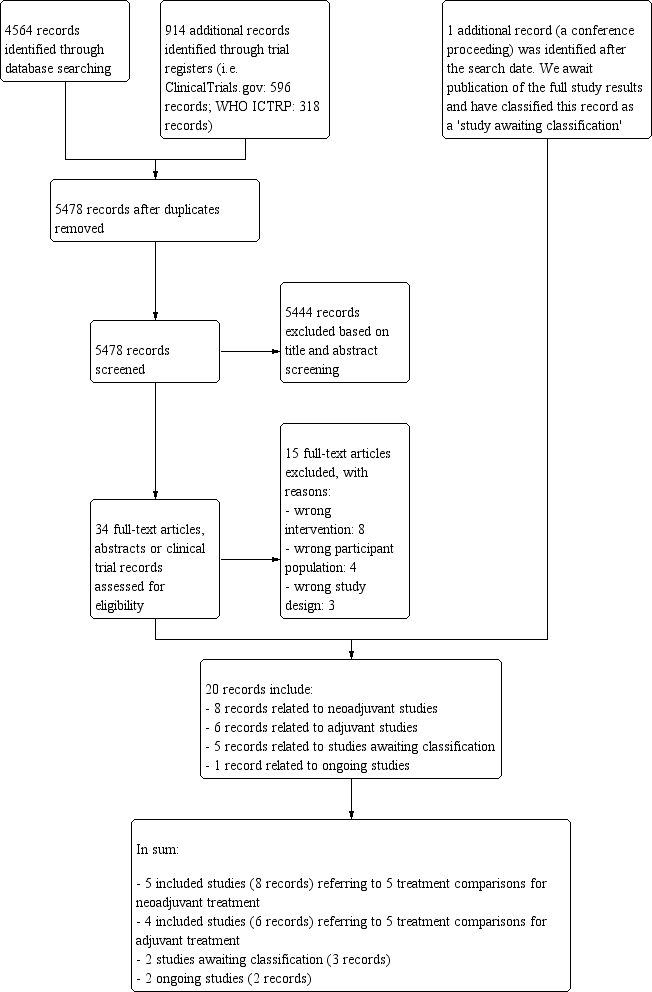

We outlined the search process in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1; Moher 2009). We identified 4564 records through searching CBCG's Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase (that included American Society of Clinical Oncology and San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium conference proceedings), and an additional 914 records from the WHO ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov. After removal of duplicate records, from 5478 unique records we excluded 5444 records based on review of the titles and abstracts retrieved. We retrieved 34 full‐text articles, abstracts or clinical trial records and on review excluded 15 records that did not meet the selection criteria (Characteristics of excluded studies table). The predominant reason for exclusion was that studies did not compare the reverse order of taxanes and anthracyclines in two treatment arms. There was one additional record relating to an abstract from a cancer conference and we wait for the results to be published. This record has been added to the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. The remaining 20 records related to:

Study flow diagram.

-

five included studies (eight records) referring to five treatment comparisons in the neoadjuvant setting (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003);

-

four included studies (six records) referring to five treatment comparisons in the adjuvant setting (Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b));

-

three studies awaiting classification (five records: Masuda 2012; NeoSAMBA; Taghian 2005); and

-

one ongoing study (one record: UMIN000003283).

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table.

Neoadjuvant studies

The five included studies involved 1415 participants (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003). Three studies used paclitaxel (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003), and two studies used docetaxel (Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005), as taxane chemotherapy. Two studies used single agent doxorubicin (Miller 2005; Stearns 2003), and three studies used epirubicin as anthracycline chemotherapy (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014; Neo‐TAnGo 2014). Two studies used epirubicin with cyclophosphamide and fluorouracil (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014), and one study used epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (Neo‐TAnGo 2014). One study used paclitaxel every two weeks with or without gemcitabine (Neo‐TAnGo 2014).

In terms of the characteristics of trial participants, one study included T1‐3, N0‐3 disease (Alamgeer 2014), one study included only participants with tumour size greater than 20 mm (T2) with or without axillary lymph node involvement (Neo‐TAnGo 2014), and two studies included participants with either tumour size greater than 20 mm (T2) or lymph node involvement (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Miller 2005). One study included participants with stage IV disease but presented data separately for stage III disease and could be used (Stearns 2003). In all studies, the majority of trial participants had axillary lymph node‐positive disease. One study included HER2‐positive participants only (ACOSOG Z1041 2013), and another study was designed and commenced prior to the introduction of trastuzumab (Neo‐TAnGo 2014). All studies had included participants whose breast cancer was HER2‐positive, hormone receptor‐positive or hormone receptor‐negative and included both premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

In relation to the outcomes assessed in the studies, the primary outcome for two of the studies was to identify a marker that correlated with tumour response to chemotherapy (Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005). One of these studies also reported overall and disease‐free survival (Alamgeer 2014). All studies used different definitions of pCR. Four studies reported on no invasive cancer in the breast or axilla (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003). Only one study reported no invasive or in situ carcinoma in the breast or axilla and was included in a separate analysis for pCR (Alamgeer 2014). No studies reported on RCB or quality of life outcomes.

One study was funded solely by a government grant (ACOSOG Z1041 2013), and four studies were supported by a government or cancer society grant combined with a research grant from a pharmaceutical company (Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003).

Adjuvant studies

The four included studies involved 280 participants and contributed to five treatment comparisons (Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). All studies used docetaxel as taxane chemotherapy. Two studies with three treatment comparisons used epirubicin with cyclophosphamide and fluorouracil (Abe 2013; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)), one study used epirubicin with cyclophosphamide (AERO B03 2007), and one study used adriamycin and cyclophosphamide (Puhalla 2008). Three treatment comparisons included dose‐dense regimens (where at least the same amount of chemotherapy was given over a shorter period of time, i.e. 300 mg/m² in total given in four cycles of fortnightly docetaxel at 75 mg/m² rather than three cycles of three‐weekly docetaxel at 100 mg/m²) (AERO B03 2007; Puhalla 2008; Wildiers 2009b). The Wildiers study had two treatment comparisons involving dose dense and conventional regimen (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b). There were two treatment comparisons that compared conventional three‐weekly regimens (Abe 2013; Wildiers 2009a).

For two studies, participants had to have axillary lymph node involvement (AERO B03 2007; Puhalla 2008), and for the other two studies they did not (Abe 2013; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). For two studies, HER2‐positive participants were able to participate if they were ineligible for or chose not to participate in adjuvant trastuzumab trials (Abe 2013; Puhalla 2008). One study did not report the HER2 status of participants (Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). Overall, a small proportion (12%) of the included participants had HER2‐positive disease.

In relation to the outcomes assessed in the studies, all studies were primarily investigating toxicity and treatment adherence. One study collected data on overall and disease‐free survival (AERO B03 2007). One study reported collecting data on quality of life and made a brief statement of the findings in the Discussion section of the published article (Puhalla 2008); numerical data were not provided.

One study provided no information about funding (Abe 2013), one study was supported by a government or cancer society grant combined with a research grant from industry (AERO B03 2007), and two studies were supported with grants from a pharmaceutical company (Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)).

Excluded studies

We excluded 15 studies (Characteristics of excluded studies table). The most common reason for exclusion was that they were not evaluating the sequencing of taxanes and anthracyclines (Akashi‐Tanaka 2017; Anonymous 2001; Buzdar 2004; Earl 2003; Skarlos 2012; Thomas 2017; Wildiers 2006). The second most common reason was inclusion of the wrong participant population (Cresta 2001; Focan 2005; SWOG S0800; Zoli 2005). The third most common reason was that they were not RCTs, rather they were either non‐randomised or retrospective studies (Cardoso 2001; Fabiano 2002). One study used different anthracycline regimens in the comparison arms when sequencing taxane (Guarneri 2010), and one study was a meta‐analysis (Albain 2012).

Studies awaiting classification

The Masuda 2012 study reported results in an abstract only. The study examined the sequence of treatments for women with HER2‐positive breast cancer in the neoadjuvant setting. There were insufficient details provided in the abstract and we await the complete trial publication. We contacted the trialists in May 2018 and we received no reply.

The Taghian 2005 study was reported in two publications though neither reported pCR (although this was listed in the clinical trials registry record), or overall survival and disease‐free survival for each treatment group. We contacted trialists in August 2018 and they responded that they have not yet analysed the clinical outcome data for each treatment group, though they intend to do so soon. This will be included in a review update.

The NeoSAMBA study was identified through searches of the clinical trial registry databases and after the search date of this review, it was noted that the study reported preliminary results in the form of a conference abstract. We await the full‐text publication of this study in 2019. The study examined the sequence of treatments for women with locally advanced HER2‐negative breast cancer and the primary outcome was pCR and secondary outcomes included disease‐free survival and overall survival.

Ongoing studies

We identified one ongoing neoadjuvant study through searches of the WHO ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov databases (UMIN000003283; Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 shows a summary of the risk of bias judgements of the included studies for each 'Risk of bias' domain. For each risk of bias domain, we combined the judgements for neoadjuvant and adjuvant studies. A summary of risk of bias assessments for each treatment setting is provided at the end of this section.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

The nine studies, relating to 10 treatment comparisons in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings, were described as randomised. Eight studies reporting nine treatment comparisons described the method of random sequence generation adequately (i.e. with low risk of bias; ACOSOG Z1041 2013; AERO B03 2007; Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Puhalla 2008; Stearns 2003; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). These studies used a biased coin minimisation algorithm, stratified randomisation or minimisation. For one study, there was insufficient information to accurately assess the method of random sequence generation (Abe 2013); the study was at unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

Four studies, reporting five treatment comparisons, were at low risk of bias for allocation concealment. These studies described central randomisation systems (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). Five studies did not describe methods of allocation concealment or did not provide sufficient detail in the trial publication and were at unclear risk of bias (Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005; Stearns 2003).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

Five studies, reporting six treatment comparisons, were described as open label (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)), while four studies provided no information in the trial publication and were likely to have been open label (Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Miller 2005; Stearns 2003). Performance bias was unlikely to be significant given that participants received both drug treatments just in reverse order. Therefore, performance bias was not viewed to be serious and studies were judged at low risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding of outcome assessments

We assessed detection bias for each outcome: overall survival, disease‐free survival, pCR (for neoadjuvant studies only), toxicity and treatment adherence (these outcomes were combined because grade of toxicity is entwined with treatment adherence, i.e. a drug dose is reduced or delayed, etc if high‐grade toxicities occur) and, quality of life.

The assessment of overall survival and disease‐free survival was perceived not be biased by a lack of blinding. Therefore, the five studies that collected or reported (or both) overall survival (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; AERO B03 2007; Alamgeer 2014; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003), and the five studies that collected or reported (or both) on disease‐free survival (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; AERO B03 2007; Alamgeer 2014; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003), were at low risk of bias.

For pCR, there was a lack of blinding perceived to be unlikely to lead to material bias given that the assessment of pCR by a pathologist is an objective assessment. In one study, two independent assessors determined pCR (Neo‐TAnGo 2014); in one study, one independent assessor determined pCR (Miller 2005); while the remaining three studies did not use an independent assessor (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014; Stearns 2003). Overall, all studies were at low risk of bias.

For outcome measures that were more likely to be influenced by a lack of blinding, that is, toxicity and treatment adherence, we considered for each study whether outcome assessments were confirmed by independent panels/adjudication committees and how toxicity outcomes were measured (e.g. blood tests). Most studies that assessed one or more of these outcomes had unclear risk of bias as there was no independent clinical review group and the toxicity measure collected (e.g. neuropathy) may have been influenced by the lack of blinding (Abe 2013; ACOSOG Z1041 2013; AERO B03 2007; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Puhalla 2008; Stearns 2003). However, one study reporting two treatment comparisons (Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)) reported only two toxicity outcomes relevant to this review – febrile neutropenia and neutropenia. These toxicities were diagnosed using blood tests and so were less likely to be influenced by the lack of blinding; therefore, they were at low risk of bias for this domain.

Only one study collected and reported quality of life information (Puhalla 2008). Participants who knew their treatment allocation completed quality of life questionnaires. However, all participants in the same study received the same treatments though in a different order; therefore, the study was at low risk of bias as lack of blinding was unlikely to influence participant‐reported responses.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies described minimal participant loss during the study and accounted for these losses; therefore, they were at low risk of bias (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Puhalla 2008; Stearns 2003; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)).

Selective reporting

Seven studies, reporting eight treatment comparisons, had either reported results for those outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial publication (Abe 2013; Miller 2005; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)) or a trial registration record with the outcomes as included in the methods and results section of the trial publication (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Puhalla 2008). ACOSOG Z1041 2013 and Neo‐TAnGo 2014 reported some additional toxicity outcomes, while in two trials, there were some changes to the primary or secondary outcomes with both adding new and important outcomes (Alamgeer 2014: pCR; Puhalla 2008: relative dose intensity and quality of life). Overall, we judged these seven studies (eight treatment comparisons) at low risk of bias. AERO B03 2007 was at high risk of bias for this domain as data related to both overall survival and disease‐free survival were not reported despite the study being completed in 2004. We contacted the authors for data and received no response (as of July 2018). Stearns 2003 was at high risk of bias due to having reported important outcomes (overall survival and recurrence) but omitted reporting the data separately for each treatment group and, therefore, the data could not be used for the treatment comparisons.

Other potential sources of bias

All studies were generally free of other sources of bias.

Summary of risk of bias by treatment setting

Neoadjuvant studies

Overall, the risk of bias was low for most domains across the neoadjuvant studies. The two main exceptions related to the lack of, or insufficient details to assess, allocation concealment (in three out of the five studies), and uncertainty in the risk of bias when assessing toxicity/treatment adherence outcomes when studies were unblinded (in all four studies reporting on this outcome). All of the studies collected data on prespecified outcomes. However, one study did not report important efficacy outcome data separately for each treatment group (Stearns 2003).

Adjuvant studies

Overall, the risk of bias was low for most domains with some concern in risk of bias being noted due to unblinding of outcome assessments for toxicity and treatment adherence. Although all studies reported the prespecified outcomes, one study omitted to report important outcome data that were collected in 2004 (AERO B03 2007). We contacted the trial authors in July 2018 and are yet to receive a reply. Therefore, we rated this study at high risk of bias for selective outcome reporting.

Effects of interventions

See: Summary of findings for the main comparison Taxane followed by anthracyclines compared to anthracyclines followed by taxane in neoadjuvant therapy for early breast cancer; Summary of findings 2 Taxane followed by anthracyclines compared to anthracyclines followed by taxane in adjuvant therapy for early breast cancer

Neoadjuvant setting

Five included studies (eight records) referred to five treatment comparisons in the neoadjuvant setting (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003). See: summary of findings Table for the main comparison.

Overall survival

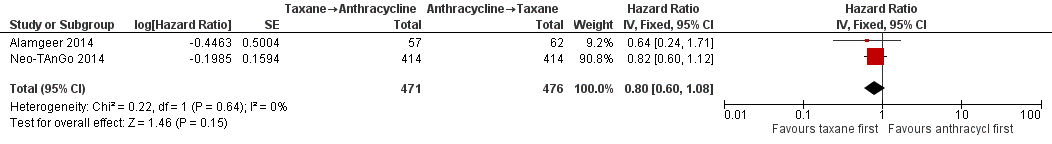

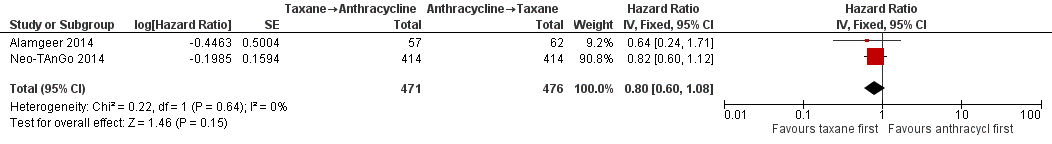

Four studies collected data on overall survival (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Alamgeer 2014; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003); however, data from one study are yet to be published (ACOSOG Z1041 2013), and one study did not report data separately for each treatment group (Stearns 2003). Based on data from two studies (947 participants), administering taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in overall survival compared to administering anthracyclines first (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.08; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 3). Only one study provided an indication of the number of deaths with Neo‐TAnGo 2014 reporting that more than 120 participants had died over the three‐year median follow‐up period.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Neoadjuvant, outcome: 1.1 Overall survival.

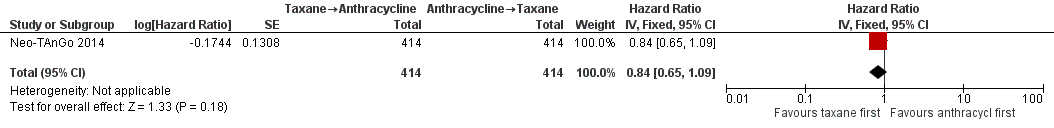

Disease‐free survival

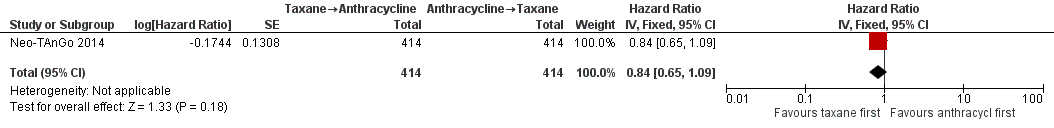

Three studies involving 1132 participants collected data on disease‐free survival (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003), but only one study reported data (Neo‐TAnGo 2014). ACOSOG Z1041 2013 collected data but the data for this type of outcome are not yet mature to present and Stearns 2003 did not report data separately for each treatment group. Based on one study, administering taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in disease‐free survival compared to administering anthracyclines first (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.09; 828 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2; Figure 4).

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Neoadjuvant, outcome: 1.2 Disease‐free survival.

Pathological complete response

All five studies provided some data relating to pathological response.

Four studies reported data on pathological response defined as the absence of cancer in the breast and axilla. Administering taxanes first resulted in little to no difference in pCR compared to administering anthracyclines first (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.38; 1280 participants; 4 studies; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3; Figure 5); however, there appeared to be a trend in favour of taxanes first.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Neoadjuvant, outcome: 1.3 Pathological complete response (pCR) includes by hormone or HER2 receptor status.

Two studies provided data by hormone receptor or HER2 (or both) status (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Neo‐TAnGo 2014). Overall, receptor status did not appear to affect the results (Analysis 1.3); however, ACOSOG Z1041 2013 was confounded with participants receiving trastuzumab throughout the trial period in the taxanes followed by anthracycline treatment arm while the other treatment group received trastuzumab only after receiving anthracyclines. Therefore, results need to be considered cautiously.

One study defined pathological response as the absence of invasive or in situ carcinoma in the breast or axillary lymph nodes (Alamgeer 2014). Based on one study, administering taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in pathological response compared to anthracyclines first (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.84; 119 participants; Analysis 1.4).

Two studies reported data relating to absence of invasive cancer in the breast and found that there was probably little or no difference between groups (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.20; 306 participants; Analysis 1.4). One study reported data relating to absence of invasive cancer in the axilla and indicated a higher response in the taxane first group compared to anthracycline first group (RR 1.66, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.66; 282 participants; Analysis 1.4).

Standardised Residual Cancer Burden score

None of the studies reported standardised RCB score.

Adverse events

Febrile neutropenia

One study collected data on febrile neutropenia (grade 3) but did not report data separately for each treatment group (Stearns 2003). In total, 5/20 women reported grade 3 neutropenic fever.

Neutropenia

Four studies collected data on neutropenia (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003); however, only one study reported the data in a useable manner (ACOSOG Z1041 2013). This was because Stearns 2003 did not report data separately for each treatment group (i.e. in total, 6/20 women reported grade 3/4 neutropenia); Miller 2005 and Neo‐TAnGo 2014 presented the incidence of neutropenia for each drug within each treatment arm and accumulating these data across a treatment arm may lead to double‐counting of toxic events.

One study presented usable data (ACOSOG Z1041 2013). Administering taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in risk of neutropenia compared to administering anthracyclines first (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.82; 280 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5). There were 45 events in 142 participants in the taxane first arm and 35 events in 138 participants in the anthracycline first arm.

Cardiac toxicity

One study presented data on cardiac toxicity (ACOSOG Z1041 2013). Administering taxanes first appeared to result in little to no difference in risk of cardiac toxicity compared to administering anthracyclines first (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.29 to 3.28; 280 participants; data not shown). The study contributed results with 10 events in 280 participants and notably administered trastuzumab and anthracycline concurrently in the intervention arm.

Pulmonary toxicity

One study presented data on pulmonary toxicity (Neo‐TAnGo 2014). Administering taxanes first appeared to result in little to no difference in risk of pulmonary toxicity compared to administering anthracyclines first (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.12 to 73.43; 828 participants; data not shown). The study reported one event of pneumonia in 828 participants.

Neurotoxicity

Three studies collected data on neurotoxicity (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Neo‐TAnGo 2014; Stearns 2003). However, two studies contributed data for the analysis (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Neo‐TAnGo 2014). Stearns 2003 did not report data separately for each treatment group (i.e. there was one case of peripheral neuropathy in 20 trial participants).

Based on two studies, administering taxanes first may have resulted in little to no difference in risk of neurotoxicity compared to administering anthracyclines first (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.65; 1108 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5). Time points and method of assessments for neurotoxicity were unclear and, therefore, the ability of these studies to meaningfully detect neurotoxicity remained unclear. Forty‐nine of 1108 participants reported grade 3 or grade 4 neurosensory difficulties.

Haematological malignancy

None of the studies reported haematological malignancy.

Treatment‐related death

Two studies reported treatment‐related death. Administering taxanes first appeared to result in little to no difference in the risk of treatment‐related death (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.93; 1108 participants; Analysis 1.5). There were two treatment‐related deaths in 1108 participants. One death was due to neutropenic sepsis and pneumonia after the third dose of paclitaxel in the taxanes first arm while the other death was due to venous thromboembolism two days after the third dose of epirubicin and cyclophosphamide in the anthracyclines first arm.

Treatment adherence

Treatment adherence was reported using measures such as number of participants who received at least a certain percentage of the planned dose, received a certain number of weeks of planned cycles, dose reductions, dose intensity and cycle delivered dose intensity (CCDI). Due to the heterogeneity in reporting treatment adherence, Table 1 shows the results for the five studies that reported this outcome. Two studies reported dose intensity (Miller 2005; Neo‐TAnGo 2014), but with different measures (i.e. calculated either as percentage of planned dose intensity delivered (Miller 2005) or CDDI (Neo‐TAnGo 2014)). These two studies did not suggest a difference in dose intensity or in CDDI between the two treatment groups.

Data could be extracted and presented for the dose reduction outcome. One study reported dose reduction and administering taxanes first probably did not increase the risk of requiring dose reductions (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.11; 280 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.6) (ACOSOG Z1041 2013).

Quality of life

None of the studies reported data on quality of life.

Adjuvant setting

Four included studies (six records) referring to five treatment comparisons in the adjuvant setting (Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). See: summary of findings Table 2.

Overall survival

None of the studies presented data for overall survival. One study collected data but reported no results (AERO B03 2007).

Disease‐free survival

None of the studies presented data for disease‐free survival. One study collected data but reported no results (AERO B03 2007).

Adverse events

Febrile neutropenia

All four studies, involving five treatment comparisons, reported febrile neutropenia. Administration of taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in the risk of febrile neutropenia (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.24 to 2.05; 4 studies with 5 treatment comparisons; 279 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1). There were four cases of febrile neutropenia in 142 participants in the taxanes first arm and six cases of febrile neutropenia in 137 participants in the anthracyclines first arm.

Neutropenia

All four studies, involving five treatment comparisons, reported neutropenia (grade 3/4). Administration of taxanes first reduced the risk of grade 3/4 neutropenia when compared with anthracyclines first (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.97; 4 studies with 5 treatment comparisons; 279 participants; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1). There were 23 events in 142 participants in the taxane first arm and 35 events in 137 participants in the anthracyclines first arm.

Cardiac toxicity

Two studies reported cardiac toxicity. Administration of taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in the risk of cardiac toxicity (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.01 to 6.99; 2 studies; 120 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence; data not shown). There were no events in the taxane first group and one event in the anthracyclines first group in a total of 120 participants.

Pulmonary toxicity

One study reported pulmonary toxicity. Administration of taxanes first may have resulted in little to no difference in the risk of pulmonary toxicity (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.85; 56 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence; data not shown). There were no events in the taxane first arm and one event in the anthracyclines first arm in a total of 56 participants.

Neurotoxicity

Three studies reported data for neurotoxicity. Administration of taxanes first may have resulted in little to no difference in the risk of neurotoxicity (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.46; 162 participants; 3 studies; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1). There were four events in 83 participants in the taxane first arm and five events in 79 participants in the anthracyclines first arm.

Haematological malignancy

None of the studies reported haematological malignancy.

Treatment‐related death

One study reported treatment‐related death. There were no events in either group (64 participants; AERO B03 2007).

Treatment adherence

Treatment adherence was reported using a variety of measures. These included dose delays, dose reductions, one‐dose reductions, number of participants who did not receive the planned number of cycles (i.e. six or eight cycles) and dose intensity. The available data have been presented separately below.

Delay in treatment

Three studies involving four treatment comparisons reported delay in treatment (AERO B03 2007; Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). Administration of taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in the risk of dose delays (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.12; 238 participants; 3 studies with 4 treatment comparisons; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.2). There were 31 dose delays in 121 participants in the taxane first arm compared to 39 dose delays in 117 participants in the anthracycline first arm.

Dose reduction

Two studies involving three treatment comparisons reported dose reductions (Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). For the taxane component (docetaxel), the taxane first regimen probably reduced the number of dose reductions compared to anthracyclines first regimen (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.73; 173 participants; 3 treatment comparisons; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.3.1). Seven dose reductions occurred in 87 participants in the taxane first arm compared to 21 dose reductions in 86 participants in the anthracycline first taxane arm. For the anthracycline component (fluorouracil, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide), the taxane first regimen probably resulted in little to no difference in the number of dose reductions compared to anthracyclines first regimen (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.18 to 5.44; 117 participants; 1 study, 2 treatment comparisons; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.3.2).

One‐dose reduction

One study reported data on one‐dose reduction (AERO B03 2007). Administration of taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in the number of one‐dose reductions compared to the anthracyclines first regimen (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.14 to 2.10; 65 participants; Analysis 2.4).

Did not receive planned cycles

Three studies reported data on participants who did not receive planned cycles (Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Puhalla 2008). Administration of taxanes first probably resulted in little to no difference in the number of planned cycles received (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.31; 163 participants; Analysis 2.5). There were 4/83 participants who did not receive the planned number of cycles in the taxane first arm compared to 9/80 participants in the anthracycline first arm.

Dose intensity

Four studies involving five treatment comparisons reported data on dose intensity (Abe 2013; AERO B03 2007; Puhalla 2008; Wildiers (Wildiers 2009a; Wildiers 2009b)). However, the presentation of data varied across the studies and only one study reported a measure of precision (in the form of a CI, standard error or standard deviation) (AERO B03 2007; median and range). Therefore, data could not be pooled using meta‐analysis. The results for all studies are provided in Table 2. Overall, the relative dose intensity (a percentage of the absolute dose intensity (actual) divided by the planned dose intensity) indicated that the taxane component within the taxanes first arm was possibly more likely to meet the expected dose compared to the anthracyclines first arm. When examining the anthracycline component of the chemotherapy schedule, the mean relative dose intensity may have been more likely to meet the expected dose in the anthracycline first arm than the taxane first arm.

Quality of life

One study reported quality of life data using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast Cancer (FACT‐B) version 4 questionnaire (Puhalla 2008). Scores were similar in both groups for a subset of 20 participants who were assessed before, during and after treatment. Numerical or further details were not provided in the trial publication.

Discusión

Resumen de los resultados principales

En el contexto neoadyuvante, es probable que haya poca o ninguna diferencia en los resultados de la supervivencia, la respuesta tumoral o la toxicidad debido a la secuencia en la cual se administran las antraciclinas y los taxanos. No hubo evidencia de efectos beneficiosos o perjudiciales significativos; sin embargo, el número de estudios y participantes que contribuyeron con datos fue pequeño. Se espera la recopilación de datos con el transcurso del tiempo para proporcionar mayor información con respecto a los resultados de supervivencia.

En el contexto coadyuvante, no hubo datos de supervivencia disponibles. Hay evidencia de certeza alta a baja en cuanto a las diferencias en la toxicidad entre los dos regímenes. La secuencia de taxanos en primer lugar redujo el riesgo de neutropenia de grado 3 o grado 4 sin diferencias observadas para otras toxicidades. La administración de taxanos primero probablemente redujo el riesgo de necesidad de reducción de la dosis para los taxanos. La capacidad de administrar taxanos con una necesidad reducida de diminución de la dosis puede dar lugar a un beneficio importante si mejora la supervivencia; sin embargo, hubo datos faltantes con respecto a la supervivencia.

Teniendo en cuenta los datos disponibles, no hubo evidencia sólida de efectos perjudiciales, efectos beneficiosos o una equivalencia debido al orden en el cual de administró el taxano y, por consiguiente, la situación clínica específica puede tener prioridad al elegir el régimen de quimioterapia.

Compleción y aplicabilidad general de las pruebas

Sólo dos estudios de la quimioterapia neoadyuvante informaron sobre el resultado primario de la supervivencia general y uno sobre el resultado secundario de la supervivencia libre de enfermedad. Dos estudios adicionales recopilaron los datos de la supervivencia (ACOSOG Z1041 2013; Stearns 2003), y se aguarda el informe de uno (ACOSOG Z1041 2013). Ningún estudio de la quimioterapia coadyuvante informó sobre los resultados de supervivencia y sólo un estudio recopiló los datos (AERO B03 2007). La mayoría eran estudios de factibilidad que evaluaban las toxicidades. Se sospecha que probablemente se recopiló una variedad más amplia de datos de la toxicidad, incluidas las toxicidades importantes evaluadas con frecuencia como la neutropenia febril y las neurotoxicidades pero no se informó en las publicaciones. Ninguno de los estudios incluyó datos numéricos para la calidad de vida. Algunos estudios tuvieron sólo un subconjunto pequeño de pacientes con enfermedades positivas para el REH2 y triple negativo. En términos generales, la revisión tuvo una generalizabilidad limitada debido a que los estudios pueden no haber incluido a todos los tipos relevantes de participantes y hubo información limitada para algunos resultados importantes.

Los resultados de esta revisión no aportan evidencia suficiente para recomendar un cambio en cuanto a la práctica local actual.

Calidad de la evidencia

En términos generales, la certeza de la evidencia a través de los dos contextos fue alta a baja. Hubo cinco estudios de la quimioterapia neoadyuvante con 1415 participantes y cuatro estudios de la quimioterapia coadyuvante con 280 participantes. Los estudios fueron no enmascarados, lo cual aumenta potencialmente el riesgo de sesgo para los dominios de la toxicidad y la calidad de vida; sin embargo, se considera que este riesgo fue pequeño debido a que todos los brazos estaban recibiendo los mismos fármacos. Por lo demás, los estudios en general se realizaron de forma adecuada desde el punto de vista metodológico. Neo‐TAnGo 2014 contribuyó con la mayor parte de los datos al metanálisis y fue un estudio informado de manera adecuada. En general, debido a la imprecisión fue difícil juzgar la consistencia de los resultados debido a que los IC fueron amplios y hubo superposición. Los estudios no informaron ni recopilaron de manera sistemática los datos sobre los resultados de la revisión y con el número más pequeño de estudios no se logró el tamaño óptimo de información. Además, en algunos casos, la duración del seguimiento fue corta o no notificada.

Sesgos potenciales en el proceso de revisión

El objetivo de esta revisión era proporcionar una evaluación minuciosa de cualquier riesgo y beneficio importante debido a la secuencia en la cual se administran las antraciclinas y los taxanos, en un contexto coadyuvante o neoadyuvante. A pesar de una amplia búsqueda en las bases de datos y las conferencias importantes es posible que no se hayan identificado todos los estudios potencialmente relevantes. Los estudios pueden haber usado un régimen de secuenciación sin haber investigado el efecto de la secuencia en la cual se administran los taxanos como un objetivo. Estos estudios pueden haber sido potencialmente excluidos en la revisión del título y el resumen.

Debido al número de estudios, no se examinó el gráfico en embudo para evaluar el sesgo de informe. Se incluyen pequeños estudios negativos en esta revisión; sin embargo, puede haber más estudios de este tipo que no se han publicado. Sólo un estudio no informó los datos de supervivencia recopilados que deberían haber estado disponibles desde la publicación inicial (AERO B03 2007). Se estableció contacto con los autores del estudio para determinar si había datos recopilados pero no informados y para obtener aclaraciones en cuanto a los datos, aunque no se recibió ninguna respuesta. En términos generales, se consideró que el riesgo de sesgo de publicación fue bajo.