Absetzen von Immunsuppressiva oder der biologischen Therapie bei Patienten mit ruhendem Morbus Crohn

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, multi‐centre, placebo controlled withdrawal trial (N = 83) 11 sites in France, 1 site in Belgium | |

| Participants | Adults (> 18 years) with CD as diagnosed by established clinical, endoscopic, radiological and histological criteria who had received continuous azathioprine therapy for > 42 months Patients were ineligible if they had: a) experienced a flare‐up while receiving azathioprine; b) had active disease at entry (CDAI score > 150); c) had isolated perianal disease; or d) were treated with azathioprine for the prevention of post‐operative recurrence | |

| Interventions | 1:1 randomization ratio Group 1: oral azathioprine once daily at the dose taken prior to study enrolment (n = 40) Group 2: placebo (n = 43) Follow‐up duration: 18 months | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: proportion of patients with relapse (defined as CDAI score > 250, a CDAI score 150‐250 on 3 consecutive weeks with an increase of > 75 points from baseline, or the need for surgery) over the 18 month study period | |

| Notes | The definition of relapse was chosen to eliminate small/transient increases of the CDAI score, which could be attributable to a cause other than relapse such as irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomization using permutation tables of 2 or 4 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not adequately described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | The placebo and azathioprine were identical in appearance and taste |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Patients filled out diary cards Biological test results were reviewed by co‐investigators who had no patient contact and recorded results in a separate case report form The endoscopists calculated the CDEIS (it is unclear, but assumed that they were blinded to clinical information) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Drop‐outs were balanced across treatment groups 37/40 in the azathioprine group completed the study compared to 40/43 in the placebo group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free from other sources of bias |

| Methods | Randmized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled withdrawal trial of azathioprine in CD (N = 51) | |

| Participants | Adults (>18 years) with CD as diagnosed by established criteria who were on azathioprine for > 6 months and had been in clinical remission for > 6 months | |

| Interventions | Group 1: oral azathioprine at the dose taken prior to study enrolment (n = 27) Group 2: placebo (n = 24) Duration of follow‐up: 12 months | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: proportion of patients with relapse (defined as a significant deterioration in clinical state requiring change in treatment as judged by two doctors unaware of the patient's treatment) over the 12 month study period | |

| Notes | This represents the first withdrawal trial of azathioprine monotherapy in CD | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Study only states the groups were randomly divided, no information on how this was performed |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not adequately described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double‐blind trial with control tablets utilized |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not adequately described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Drop‐outs were balanced across treatment groups 21/24 in the azathioprine group completed the study compared to 25/27 in the placebo group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | This study appears to be free from other sources of bias |

| Methods | Randomized open‐label trial (N = 81: UC N = 36; CD N = 45) | |

| Participants | Patients with IBD (UC and CD) in deep remission for at least 6 months who were treated with combination therapy (infliximab and azathioprine) for at least one year | |

| Interventions | Cohort A: azathioprine and infliximab continued (usual care) (UC n = 12; CD n = 16) Cohort B: azathioprine dose halved (UC n = 13; CD n = 14) Cohort C: azathioprine stopped (infliximab continued as monotherapy) (UC = 11; CD n = 15) | |

| Outcomes | Primary: clinical relapse (CDAI score > 220 with a delta CDAI > 70 from the previous assessment and/or need to change the original therapeutic regimen because of adverse events or drug intolerance Secondary: infliximab trough levels and anti‐drug antibodies | |

| Notes | Authors were contacted, and they provided information regarding CD‐specific results Patients with CD from cohorts A and C (n = 31) were included in this review | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Patients were randomised into three parallel groups with randomisation balanced by blocks" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The randomisation was not stratified and was centrally performed by an interactive web response system (IWRS)" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Open‐label |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Open‐label |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Drop‐outs were balanced across treatment groups 13/16 in the combination therapy group completed the study compared to 10/15 in the group where azathioprine was stopped |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All primary and secondary outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Premature stopping of the trial due to slow enrolment |

| Methods | Randmized, open‐label controlled trial (N = 80) | |

| Participants | Patients (> 16 years) with luminal CD on a combination regimen consisting of infliximab 5 mg/kg IV and an immunosuppressant (azathioprine/6‐mercaptopurine or methotrexate) for at least 6 months Patients must have had full disease control at entry | |

| Interventions | 1:1 randomization ratio Group 1: azathioprine and infliximab continued (n = 40) Group 2: placebo with only infliximab continued (n = 40) Duration of follow‐up: 104 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: the proportion of patients who required a change in the dosing interval or completely stopped infliximab therapy due to disease flare (i.e. clinical relapse) Secondary outcomes: infliximab trough levels, adverse events and mucosal healing | |

| Notes | This study was not powered as a non‐inferiority trial; continuation therapy was assumed to be superior. To study non‐inferiority, > 250 patients per treatment arm would be required. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not adequately described (no explicit statement about the method used) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Centralized randomization was performed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Due to the open‐label design no placebo was given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Outcome assessment was not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Drop‐outs were balanced across treatment groups 29/40 in the combination therapy group completed the study compared to 31/40 in the group where azathioprine was stopped |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | This study appears to be free from other sources of bias |

| Methods | Randomized, open‐label, controlled trial (N = 29) | |

| Participants | Patients with quiescent CD who had received a continuous dose of azathioprine for at least 2 years | |

| Interventions | Group 1: azathioprine withdrawal (n = 15) Group 2: continued azathioprine treatment at an unchanged dose (n = 14) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: clinical relapse (defined as a rise in CDAI > 75 with a total CDAI > 150; or, any increased disease activity requiring new medical or surgical treatment) Follow‐up duration was 12 months | |

| Notes | Randomization took place after stratification by azathioprine dose Low azathioprine dose was defined as < 1.60 mg/kg/day | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer generated 1:1 randomization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization was performed centrally |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Open‐label trial; participants and personnel not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | No blinding of outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | There was only one drop‐out (in the azathioprine group) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | This study appears to be free from other sources of bias |

| Methods | Randmized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled withdrawal trial (N = 52) | |

| Participants | CD patients in stable clinical remission (CDAI < 150) on azathioprine for > 4 years | |

| Interventions | 1:1 randomization ratio Group 1: placebo (n = 26) Group 2: azathioprine at dose prior to study entry (n = 26) Follow‐up duration: 24 months | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Time interval between first intake of the study drug and disease relapse Secondary outcomes: Disease activity (CDAI), quality of life, and laboratory parameters associated with active disease (CRP, serum hemoglobin, serum albumin, and platelet count) | |

| Notes | Slow recruitment led to premature cessation of the study | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization tables were used according to a 1:1 ratio |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Centralized randomization was performed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Double‐blind: medicine was provided in identical‐appearing tablets |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not adequately described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Drop‐outs were balanced across treatment groups 19/26 in the azathioprine group completed the study compared to 23/26 in the placebo group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Premature stopping of the trial due to slow enrolment. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Reduced dose (not withdrawal) of therapy | |

| Case report | |

| Letter (not study) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| Retrospective study | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| Letter (not study) | |

| Retrospective study | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| Pediatric study | |

| Pediatric study | |

| Pediatric study | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| CD specific data unavailable | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| Retrospective study | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| < 6 months of treatment prior to withdrawal | |

| < 6 months of treatment prior to withdrawal | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| Pediatric study | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| Review article | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Pediatric study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Pediatric study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Pediatric study | |

| Pediatric study | |

| Reduced dose (not withdrawal) of therapy | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| < 6 months of treatment prior to withdrawal | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| No control (usual care) | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Retrospective study | |

| Pediatric study | |

| No control (usual care) |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Discontinuation of infliximab therapy in patients With CD during sustained complete remission (STOP IT) |

| Methods | Prospective, double‐blind, 2‐arm RCT |

| Participants | Patients with luminal Crohn's disease in sustained complete remission on infliximab |

| Interventions | Arm 1: infliximab at an unchanged dose Arm 2: placebo |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: proportion of patients who maintain remission (CDAI < 150) |

| Starting date | Start date: November 2012 |

| Contact information | Sine Schnoor Buhl MD, [email protected] Mark Ainsworth MD PhD DMSc, [email protected] |

| Notes | NCT01817426 The recruitment status of this study is unknown. The completion date has passed and the status has not been verified in more than two years. |

| Trial name or title | A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing infliximab‐antimetabolites combination therapy to antimetabolites monotherapy and infliximab monotherapy in Crohn's disease patients in sustained steroid‐free remission on combination therapy (SPARE) |

| Methods | Prospective, open‐label, three‐arm RCT |

| Participants | Patients with luminal CD in steroid‐free remission for at least 6 months who have received combination therapy with infliximab and anti‐metabolites for at least 1 year N = 300 (100 per arm) |

| Interventions | Study treatment: Infliximab; 6‐mercaptopurine, azathioprine or methotrexate Arm 1: combination therapy with infliximab and anti‐metabolite continued Arm 2: discontinue infliximab, continue anti‐metabolite Arm 3: discontinue anti‐metabolite, continue infliximab |

| Outcomes | Co‐primary outcome: clinical relapse rate at 2 years; mean remission duration within 2 years |

| Starting date | Study duration: 2 + 2 years Enrollment: 2 years + 1 year Follow‐up: 2 years Start date: October 2015 Estimated end date: January 2020 |

| Contact information | Edouard Louis PhD, [email protected] |

| Notes | NCT02177071 |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

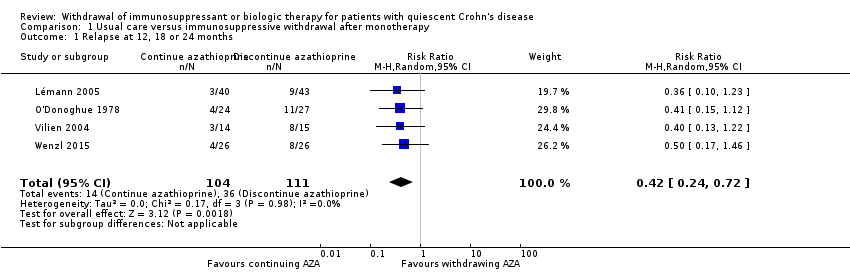

| 1 Relapse at 12, 18 or 24 months Show forest plot | 4 | 215 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.24, 0.72] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 1 Relapse at 12, 18 or 24 months. | ||||

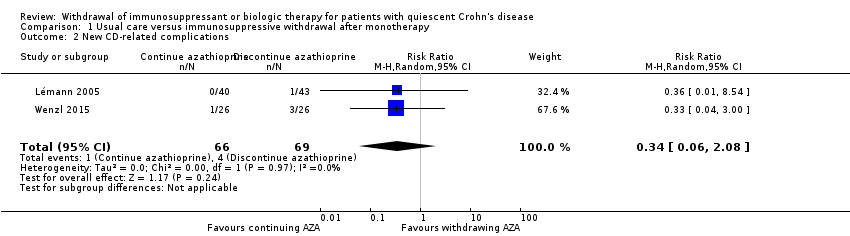

| 2 New CD‐related complications Show forest plot | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.06, 2.08] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 2 New CD‐related complications. | ||||

| 3 Adverse events Show forest plot | 3 | 186 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.67, 1.17] |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 3 Adverse events. | ||||

| 4 Serious adverse events Show forest plot | 2 | 134 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.29 [0.35, 30.80] |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 4 Serious adverse events. | ||||

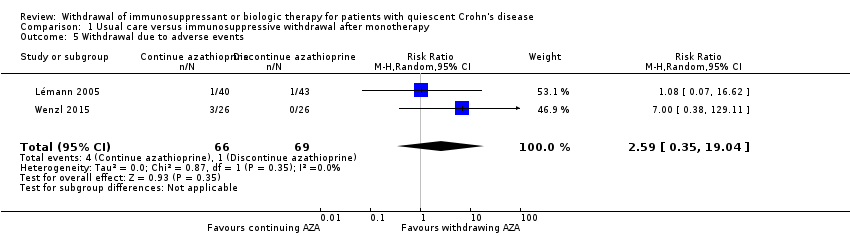

| 5 Withdrawal due to adverse events Show forest plot | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.59 [0.35, 19.04] |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 5 Withdrawal due to adverse events. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

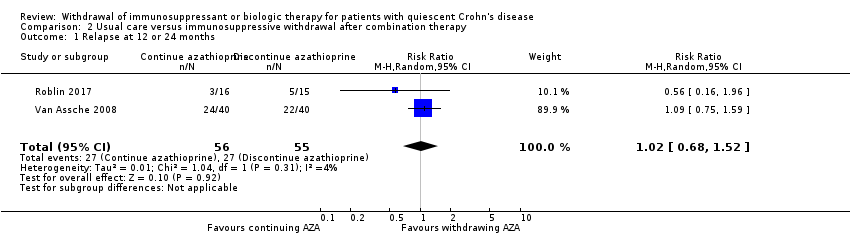

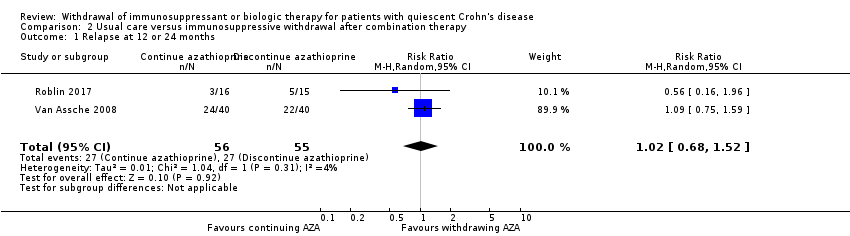

| 1 Relapse at 12 or 24 months Show forest plot | 2 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.68, 1.52] |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy, Outcome 1 Relapse at 12 or 24 months. | ||||

| 2 Adverse events Show forest plot | 2 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.44, 2.81] |

| Analysis 2.2  Comparison 2 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy, Outcome 2 Adverse events. | ||||

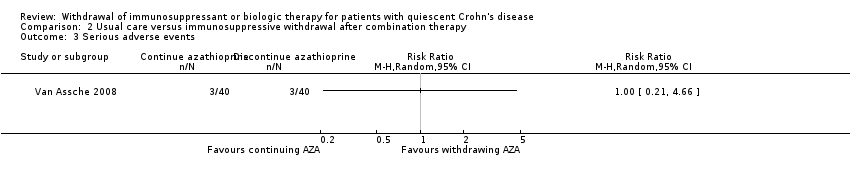

| 3 Serious adverse events Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.3  Comparison 2 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy, Outcome 3 Serious adverse events. | ||||

Study flow diagram.

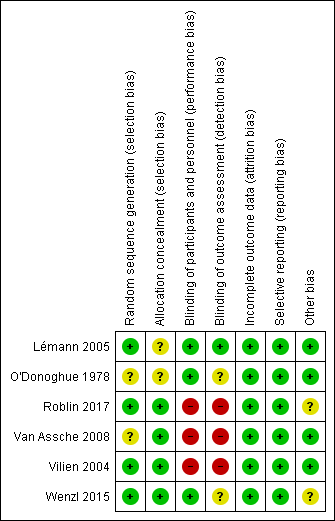

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 1 Relapse at 12, 18 or 24 months.

Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 2 New CD‐related complications.

Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 3 Adverse events.

Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 4 Serious adverse events.

Comparison 1 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy, Outcome 5 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

Comparison 2 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy, Outcome 1 Relapse at 12 or 24 months.

Comparison 2 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy, Outcome 2 Adverse events.

Comparison 2 Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy, Outcome 3 Serious adverse events.

| Usual care compared to immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy for patients with quiescent Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with quiescent Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy | Risk with usual care | |||||

| Relapse at 12, 18 or 24 months | Study population | RR 0.42 | 215 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Sparse data (50 events) | |

| 324 per 1,000 | 136 per 1,000 | |||||

| New CD‐related complications | Study population | RR 0.34 | 135 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | Very sparse data (5 events) | |

| 58 per 1,000 | 20 per 1,000 | |||||

| Adverse events | Study population | RR 0.88 | 186 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Sparse data (45 events) | |

| 240 per 1,000 | 211 per 1,000 | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Study population | RR 3.29 | 134 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | Very sparse data (2 events) | |

| 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 | |||||

| Withdrawal due to adverse events | Study population | RR 2.59 | 135 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | Very sparse data (5 events) | |

| 14 per 1,000 | 38 per 1,000 | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias for blinding in one study and unclear risk of bias in three studies in the pooled analysis 2 Downgraded one level due to sparse data 3 Downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias in the two studies in the pooled analysis 4 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data 5 Downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias in the three studies in the pooled analysis | ||||||

| Usual care compared to immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy for patients with quiescent Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients with quiescent Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy | Risk with usual care | |||||

| Relapse at 12 or 24 months | Study population | RR 1.02 | 111 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Sparse data (54 events) | |

| 491 per 1,000 | 501 per 1,000 | |||||

| Adverse events | Study population | RR 1.11 | 111 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Sparse data (51 events) | |

| 455 per 1,000 | 505 per 1,000 | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Study population | RR 1.00 | 80 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | Very sparse data (6 events) | |

| 75 per 1,000 | 75 per 1,000 | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1 Downgraded one level due to high risk of bias for blinding 2 Downgraded one level due to sparse data 3 Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data | ||||||

| Comparison 1: Usual care versus immunosuppressive withdrawal after monotherapy | |||

| Outcome | Random Effects RR (95% CI) | Fixed Effect RR (95% CI) | Impact |

| 1.1 Relapse at 12, 18 or 24 months | 0.42 (0.24‐0.72) | 0.42 (0.24‐0.72) | No change |

| 1.2 New CD‐related complications | 0.34 (0.06‐2.08) | 0.34 (0.06‐2.08) | No change |

| 1.3 Adverse events | 0.88 (0.67‐1.17) | 0.97 (0.71‐1.32) | Minimal |

| 1.4 Serious adverse events | 3.29 (0.35‐30.80) | 3.29 (0.35‐30.80) | No change |

| 1.5 Withdrawal due to adverse events | 2.59 (0.35‐19.04) | 3.10 (0.49‐19.41) | Minimal |

| Comparison 2: Usual care versus Immunosuppressive withdrawal after combination therapy | |||

| Outcome | Random Effects RR (95% CI) | Fixed Effect RR (95% CI) | |

| 2.1 Relapse at 12 or 24 months | 1.02 (0.68‐1.52) | 0.99 (0.69‐1.43) | Minimal |

| 2.2 Adverse events | 1.11 (0.44‐2.81) | 1.04 (0.73‐1.47) | Minimal |

| 2.3 Serious adverse events | No pooling | No pooling | No pooling |

| Study | Length of remission prior to drug withdrawal | Definition of remission prior to drug withdrawal |

| Minimum 6 months | CDAI ≤ 150 and fecal calprotectin levels < 250 μg/g | |

| Mean 62 months (standard deviation 26 months); Minimum 42 months | Clinical remission (CDAI ≤ 150) and no need for medical/surgical therapy in the previous 42 months | |

| Minimum 6 months | Clinical remission not otherwise specified | |

| Minimum 6 months | Clinical response to infliximab and disease control | |

| Not specified | Clinical remission: physician's global assessment | |

| Minimum 12 months | Clinical remission, no need for new medical therapy in the previous 12 months |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Relapse at 12, 18 or 24 months Show forest plot | 4 | 215 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.24, 0.72] |

| 2 New CD‐related complications Show forest plot | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.06, 2.08] |

| 3 Adverse events Show forest plot | 3 | 186 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.67, 1.17] |

| 4 Serious adverse events Show forest plot | 2 | 134 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.29 [0.35, 30.80] |

| 5 Withdrawal due to adverse events Show forest plot | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.59 [0.35, 19.04] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Relapse at 12 or 24 months Show forest plot | 2 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.68, 1.52] |

| 2 Adverse events Show forest plot | 2 | 111 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.44, 2.81] |

| 3 Serious adverse events Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |