Вмешательства при некротизирующих инфекциях мягких тканей у взрослых

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to studies awaiting assessment

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Prospective, Phase IIA, randomised, parallel‐group, placebo‐controlled, double‐blinded study Multicentric (6 centres) in the USA Period of Inclusion: December 2011 to August 2012 | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Baseline characteristics N = 43, mean age of 50.7 years and 65% of men | |

| Interventions | Each participant was treated with standardised empiric antibiotic therapy, and underwent surgical debridement of necrotic tissue Intervention 1 (n = 17) AB103, one dose intravenous (IV), 0.5 mg/kg, < 6 hours after diagnosis (infusion before, during or after the surgery) Intervention 2 (n = 15) AB103, one dose IV 0.25 mg/kg, < 6 hours after diagnosis (infusion before, during or after the surgery) Intervention 3 (n = 11) Placebo IV, < 6 hours after diagnosis (infusion before during or after the surgery) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome

Secondary outcomes

| |

| Notes | Financial support and the drug for this trial was provided by the manufacturer Atox Bio Ltd. Authors declared conflict of interest for Bayer HealthCare, BayerSchering Pharma, Novartis, GlaxoSmith Kline and Wyeth. * outcomes reported that were of interest in the review | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “Patients were randomised by a computer‐generated system to receive placebo or a low or high dose of AB103 in a 10:15:15 ratio.” Comment: computer‐generated random sequence is adequate |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: there was no description of the method used to guarantee allocation concealment |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Quote “double blinded” Comment: placebo‐controlled with similar adverse‐effect profile reported. However, concerning the risk of performance bias, 2/43 (4.6%) patients randomised had received co‐treatment IVIG and HBO and the group of these two patients was not indicated. Authors did not specify the method of blinding of physicians and participants but they assess that all investigators and care providers remained masked throughout the study. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote “double blinded" "investigators remained blinded throughout the study" Comment: there was no clear description of the process used to guarantee blinding of the assessor but it was a placebo‐controlled study with similar adverse‐effect profile reported and assessment of outcome was objective: death. Then we considered there was a low risk of detection bias for investigator‐reported outcomes for the same reasons. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Quote “Because drug administration may have started before definitive surgical diagnosis of NSTI, a modified ITT population was defined as patients in the ITT analysis who were properly randomised, treated (received AB103 or placebo), and assessable (definitive surgical diagnosis of NSTI).” Comment: three patients were excluded from the ITT population; 1/11 (9%) in the placebo group who did not meet the clinical diagnosis of NSTI and 2/15 (13.3%) in the high‐dose group. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: in accordance with the protocol available in clinical trials.gov (NCT01417780) |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias identified |

| Methods | Randomised, blinded, parallel‐group, placebo‐controlled trial Monocentric at Copenhagen University Hospital, where the management of patients with NSTI in Denmark is centralised Period of inclusion: 7 April 2014 to 1 March 2016 | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Baseline characteristics N = 100, Mean age of 60 years and 60% of men | |

| Interventions | Each patient was treated in accordance with the clinical protocols in place at Copenhagen University Hospital with standardised empiric antibiotic therapy (meropenem, clindamycin and ciprofloxacin), repeated surgical revisions, three sessions of hyperbaric oxygenation; sepsis, and supportive intensive care. Intervention 1 (N = 50) IVIG (Privigen, CSL Behring, Bern,Switzerland), 25 g/day for three consecutive days. The first dose of trial medicine was given immediately after arrival to the ICU or in the operating room before admission to ICU. Intervention 2 (N = 50) Equivalent amount of intravenous 0.9% saline for three consecutive days (placebo) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome

Secondary outcomes

| |

| Notes | * outcomes reported that were of interest in the review Authors declared conflict of interest for CSL Behring. Financial support from Fresenius Kabi, Germany, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Denmark, was declared. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were randomised 1:1 to IVIG or placebo. Two allocation lists with variable block sizes of 2, 4 and 6 were computer generated." Comment: computer‐generated random sequence is adequate |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Two allocation lists with variable block sizes of 2, 4 and 6 were computer generated to form two separate boxes that contained sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed envelopes" "Patients were randomised by dedicated personnel who drew the next envelope from the box according to the site of NSTI. The randomisation note was handed to an ICU nurse not otherwise involved in the care of the patient who placed both IVIG and 0.9% saline in a black, opaque plastic bag, inserted an orange‐coloured infusion set into the allocated intervention (IVIG or saline) and sealed the bag with a plastic strip (more details are given in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM)." Comment: the method used to guarantee allocation concealment seems to be adequate |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The randomisation note was handed to an ICU nurse not otherwise involved in the care of the patient who placed both IVIG and 0.9% saline in a black, opaque plastic bag, inserted an orange‐coloured infusion set into the allocated intervention (IVIG or saline) and sealed the bag with a plastic strip." "Patients, clinical staff caring for the patients, research staff, the statistician and the authors when writing the first draft for the abstract (supplementary results in the ESM) were all blinded to the intervention." Comment: the method used to guarantee blinding of participants and personnel was adequate and well described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients, clinical staff caring for the patients, research staff, the statistician and the authors when writing the first draft for the abstract (supplementary results in the ESM) were all blinded to the intervention" "The statistician (TL) did the analyses while still blinded to the intervention according to the statistical analysis plan." Comment: the method used to guarantee blinding of outcome assessment was well described and primary outcome is a patient‐reported outcome. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Quote: "129 patients were screened, of whom 100 were enrolled; 50 patients were assigned to the IVIG group and 50 patients to the placebo group" "Of the 100 patients randomised, 87 were included in the intention‐to‐treat analysis." Comment: 100 patients were randomised but the SF‐36 could not be obtained from 13 patients, thus analysis of primary outcome was based on 87patients. For the primary outcome, there were no data available for 38% of patients in each group with 25% of death and 13% of missing data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: in accordance with the protocol available in clinical trials.gov NCT02111161 |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: There was baseline imbalance: number of patients who had received IVIG before randomisation was higher in placebo group 20 (40%) than in IVIG group 8 (16%) and number of patients with acute kidney injury was higher in IVIG group 5 (10%) than in placebo group 1 (2%). This is a placebo‐controlled trial, however nearly half of patients in placebo group had received one dose of IVIG before randomisation. |

| Methods | Prospective, non‐inferiority randomised controlled, open‐label, parallel‐group trial Multicentric, 74 centres, worldwide Period of inclusion: April 2001 to April 2002 | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Baseline characteristics ITT population Subgroup of NSTI (n = 54): 57.4% of male; mean age 52.2 years (provided upon a request to the authors) | |

| Interventions | Intervention 1 (Per protocol (PP), n = 315); abscess n = 98; necrotizing fasciitis, n = 22; surgical wound infection n = 9; diabetic foot n = 49; complicated erysipelas n = 101; infected traumatic lesion n = 21; infected ischaemic ulcers n = 6; complicated cellulitis n = 9. moxifloxacin 400 mg per day intravenous (IV), for at least 3 days, followed by moxifloxacin 400 mg orally, once daily, for 7–21 days Intervention 2 (PP, n = 317): abscess n = 93, necrotizing fasciitis, n = 13, surgical wound infection n = 13, diabetic foot n = 63, complicated erysipelas n = 95, infected traumatic lesion n = 19, infected ischaemic ulcers n = 4, complicated cellulitis n = 17 amoxicillin‐clavulanate, IV 1000 mg/200 mg three times daily for at least 3 days, followed by amoxicillin‐clavulanate 500 mg/125 mg orally, three times daily, for 7–21 days | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome

CR at the TOC, days 14‐28, visit was defined as: cure (total resolution or marked improvement of all cSSSI signs and symptoms; no additional or alternative antimicrobial treatment necessary). Evaluations (both the visual description of the lesion and the assessment of clinical outcome) were performed by investigators. Secondary outcomes

| |

| Notes | This study was sponsored by Bayer HealthCare AG. Authors declared conflict of interest for Atox Bio Ltd and Biomedical Statistical Consulting, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania. * outcomes reported that were of interest in the review | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “randomised into two groups in a 1:1 ratio” Comment: the method used to generate the allocation sequence was not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were randomised into two groups in a 1:1 ratio to receive either moxifloxacin or the control regimen." Comment: there was no mention of how allocation concealment was guaranteed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: “open label” Comment: both participants and study personnel were aware of the assigned treatment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: “open‐label”, “Clinical outcomes were assessed bimodally as cure or failure, such that patients with only limited improvement in clinical status and partial resolution of symptoms would conservatively be considered as failures." Comment: assessment was performed by investigators who were not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: number of randomly assigned participants: 804 Number of analysed participants for the main outcome per protocol: 632 Patients withdrawn: 172 The main reasons for withdrawal after randomisation (moxifloxacin vs amoxicillin‐clavulanate) were adverse events (6.2% vs 3.8%), insufficient therapeutic effect (4.2% vs 5.3%), patient lost to follow‐up (3.9% vs 5.3%), and protocol violation (3.4% vs 2.8%) (P > 0.1 in all cases). There was a high rate of withdrawal mainly due to serious adverse events and insufficient therapeutic effect. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no protocol was available, however, the outcomes predefined in the methods were well reported in the results section. |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: there was baseline imbalance; number of patients in the NSTI subgroup was two‐fold higher in the moxifloxacin group (36/54) treatment than in the amoxicillin‐clavulanate group (18/54) treatment |

AIDS: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; cSSSI: complicated skin and skin structure infections; cSSTI: complicated skin and soft tissue infection;CR: clinical response; ESM: electronic supplementary material; HBO: hyperbaric oxygen therapy;ICU: intensive care unit; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin; ITT: intention‐to‐treat;IV: intravenous; NSTI: necrotizing soft tissue infections; PCS: physical component summary; PP: per protocol; RBC: red blood cells; RRT: renal replacement therapy; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score; SF‐36: the Short Form (36) Health Survey; TOC: test of cure; WBC: white blood cells.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| The study was not a randomised controlled trial. | |

| The study compared wound care dressings after surgery and not an intervention to treat NSTI. | |

| The study included patients with skin and soft tissue infection with no clear definition; we were unable to contact the main author (deceased). | |

| The study compared wound care dressings after surgery and not an intervention to treat NSTI. | |

| The study was not a randomised controlled trial. | |

| The study's cross‐over design was not relevant for assessment of outcomes. | |

| The study's cross‐over design was not relevant for assessment of outcomes. | |

| The study was not a randomised controlled trial. | |

| The definition of necrotizing soft tissue infection was inaccurate and included diabetic foot infection and Ischaemic gangrene. | |

| The study was not a randomised controlled trial. | |

| The study compared wound care dressings after surgery and not an intervention to treat NSTI. | |

| The study was not a randomised controlled trial. | |

| The study compared wound care dressings after surgery. |

NSTI: necrotizing soft tissue infection

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | This was a randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Participants with a streptococcal toxic shock syndrome with or without NSTI |

| Interventions | Intravenous immunoglobulin G therapy versus placebo |

| Outcomes | Mortality at 28 days Time to resolution of shock Time to no further progression of the tissue infection Survival on day 180 |

| Notes | Outcomes in the subgroup of patient with NSTI are not available. Email to the study authors without answer |

| Methods | This was a randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Participants with serious surgical infections, including intraabdominal, pelvic, biliary tract, and necrotizing soft‐tissue infections suspected of containing B.fragilis |

| Interventions | Moxalactam versus Mefoxitin, with or without tTobramycin |

| Outcomes | Cure rates |

| Notes | Outcomes in the subgroup of patient with NSTI are not available. Email to the study authors without answer |

NSTI: necrotizing soft tissue infection

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Phase III efficacy and safety study of AB103 in the treatment of patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections (ACCUTE) |

| Methods | This was a randomised, double‐blind controlled trial |

| Participants | Participants with a necrotizing soft tissue infection |

| Interventions | AB103 0.5 mg/kg vs placebo |

| Outcomes | Clinical composite success end point (Time frame: 28 days) Safety measures: adverse events Safety measures: clinical safety laboratory Safety measures: secondary infections Recovery from acute kidney injury Time to resolution of SOFA score to ≤ 1 Critical care and hospital stay parameters: ICU days Critical care and hospital stay parameters: ventilator days Critical care and hospital stay parameters: hospital length of stay |

| Starting date | September 2015 |

| Contact information | Eileen M Bulger, MD Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center |

| Notes |

ICU: intensive care unit; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Mortality within 30 days Show forest plot | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.39, 23.07] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Moxifloxacin versus amoxicillin‐clavulanate, Outcome 1 Mortality within 30 days. | ||||

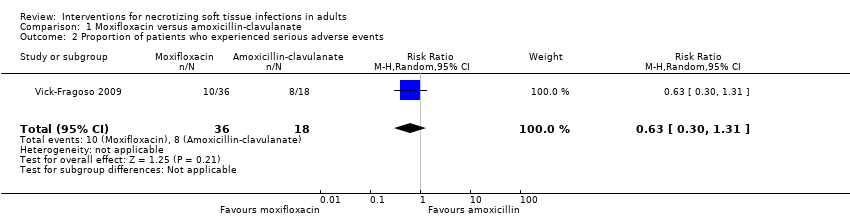

| 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events Show forest plot | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.30, 1.31] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Moxifloxacin versus amoxicillin‐clavulanate, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

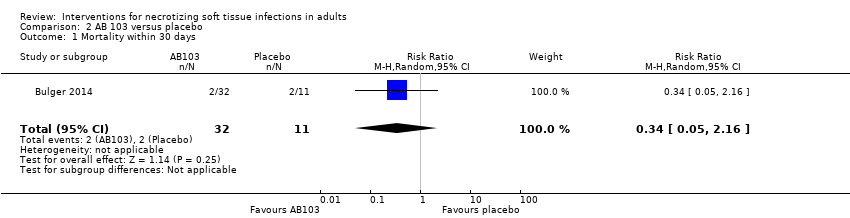

| 1 Mortality within 30 days Show forest plot | 1 | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.05, 2.16] |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 AB 103 versus placebo, Outcome 1 Mortality within 30 days. | ||||

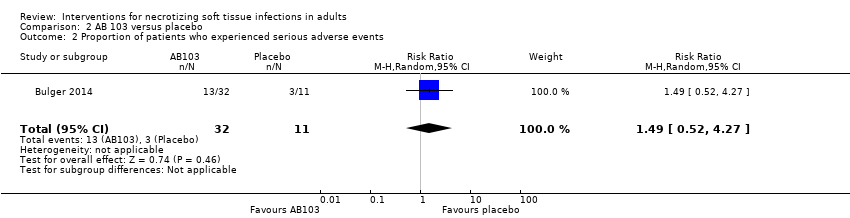

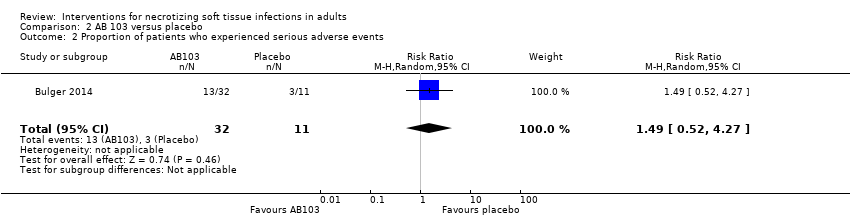

| 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events Show forest plot | 1 | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.49 [0.52, 4.27] |

| Analysis 2.2  Comparison 2 AB 103 versus placebo, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Mortality within 30 days Show forest plot | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.42, 3.23] |

| Analysis 3.1  Comparison 3 IGIV versus placebo, Outcome 1 Mortality within 30 days. | ||||

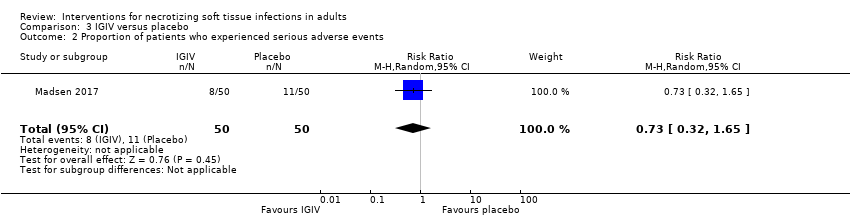

| 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events Show forest plot | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.32, 1.65] |

| Analysis 3.2  Comparison 3 IGIV versus placebo, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events. | ||||

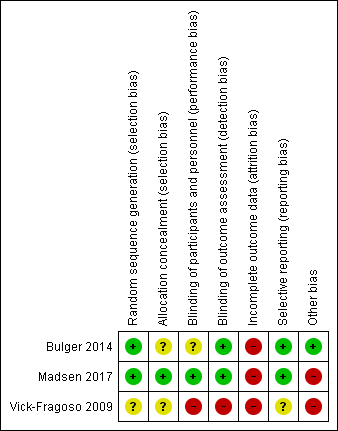

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Moxifloxacin versus amoxicillin‐clavulanate, Outcome 1 Mortality within 30 days.

Comparison 1 Moxifloxacin versus amoxicillin‐clavulanate, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events.

Comparison 2 AB 103 versus placebo, Outcome 1 Mortality within 30 days.

Comparison 2 AB 103 versus placebo, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events.

Comparison 3 IGIV versus placebo, Outcome 1 Mortality within 30 days.

Comparison 3 IGIV versus placebo, Outcome 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events.

| Moxifloxacin compared to amoxicillin‐clavulanate for NSTI | ||||||

| Patient or population: NSTI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality/certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with Amoxicillin‐clavulanate | Risk with Moxifloxacin | |||||

| Mortality | Study population | RR 3.00 | 54 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | Data from a larger trial including several types of soft tissue infections; total number of included patients N = 804 | |

| 6 per 100 | 17 per 100 | |||||

| Serious adverse events (SAE) | Study population | RR 0.63 | 54 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | Description of nature of serious adverse events was not available | |

| 44 per 100 | 28 per 100 | |||||

| Survival time | — | — | — | 54 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | The median time of death after start of antibiotic treatment was shorter in the moxifloxacin group than in the amoxicillin‐clavulanate group (10.5 days versus 42 days) (not possible to calculate hazard ratio with the data provided) |

| Assessment of long‐term morbidity | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Assumed risk for mortality was based on data of the literature (Audureau 2017; May 2009). For serious adverse effects it was based on the results of the trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| aDowngraded by five levels to very low certainty of evidence. We downgraded two levels because of high risk of bias regarding blinding (open label trial) and high risk for attrition bias because of a high rate of withdrawal (20%). We downgraded one level for serious imprecision because of small sample size (and CI of RR included 1, where reported). We downgraded a further two levels because no clear criteria for clinical diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis were provided and because antibiotic used as comparator is not relevant (indirectness) | ||||||

| AB103 compared to Placebo for NSTI | ||||||

| Patient or population: NSTI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality/certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with Placebo | Risk with AB103 | |||||

| Mortality | Study population | RR 0.34 | 43 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | — | |

| 23 per 100* | 6 per 100 | |||||

| Serious adverse events (SAE) | Study population | RR 1.49 | 43 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | There were no data about the nature of serious adverse events reported | |

| 27 per 100 | 41 per 100 | |||||

| Survival time | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| Assessment of long‐term morbidity | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Assumed risk for mortality was based on data of the literature (Audureau 2017; May 2009). For serious adverse effects it was based on the results of the trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| aDowngraded by three levels: one level for high risk of attrition bias, one level for no clear clinical definition of criteria for necrotizing fasciitis diagnosis at inclusion (indirectness), and one level for serious imprecision because of small sample size and CI included no difference | ||||||

| Intravenous immunoglobulin compared to placebo for NSTI | ||||||

| Patient or population: NSTI | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality/Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Intravenous immunoglobulin | |||||

| Mortality | Study population | RR 1.17 | 100 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | — | |

| 0 per 100 | 0 per 100 | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 23 per* 100 | 21 per 100 | |||||

| Serious adverse events (SAE) | Study population | RR 0.73 | 100 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Serious adverse reactions included acute kidney injury, allergic reactions, aseptic meningitis syndrome, haemolytic anaemia, thrombi, and transmissible agents | |

| 22 per 100 | 16 per 100 | |||||

| Survival time | — | — | — | 100 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The median time of death was shorter in the IVIG group than in the placebo group (25 days versus 49 days) (not possible to calculate hazard ratio with the data provided) |

| Assessment of long‐term morbidity | — | — | — | — | — | Not reported |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Assumed risk for mortality was based on data of the literature (Audureau 2017; May 2009). For serious adverse effects it was based on the results of the trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| aDowngraded by two levels: one level for high risk of attrition bias (38% lost of follow‐up); other bias: imbalance at baseline for one dose 25 IVIG received before randomisation (40% in placebo group vs 16% IVIG group). One level for indirectness as a minority of patients have an infection linked to bacteria producing toxins | ||||||

| Term used | Explanation |

| Adjuvant treatment | Treatment that is given in addition to the primary or initial therapy to improve its effectiveness |

| Empiric antimicrobial therapy | Antimicrobial therapy given before the specific bacteria causing an infection is known |

| Aseptic meningitis | Serious inflammation of the linings of the brain not caused by pyogenic bacteria |

| Empiric antibiotic therapy | Antibiotics that acts against a wide range of bacteria |

| Bullae | Blisters on the skin usually more than 5 mm in diameters |

| Cirrhosis | Advanced liver disease |

| Crepitus | Clinical signs characterised by a peculiar sound under the skin |

| Debridement | Surgery excision of necrotic tissues (medical removal of dead, damaged, or infected tissue) |

| Endotoxin | A toxin contained in bacteria that is released only when the bacteria are broken down |

| Exotoxin | A toxin that is secreted by bacteria into the surrounding medium |

| Fascia | A fibrous connective tissue that surrounds muscle and other soft tissue. Fasciae are classified according to their distinct layers and their anatomical location: superficial fascia and deep (muscle) fascia |

| Fulminant inflammatory response | Systemic inflammatory response |

| Gram‐negative bacteria | Class of bacteria gram‐negative staining |

| Haemolytic anaemia | Decrease in the total amount of red blood cells due to the abnormal breakdown of red blood cells |

| Hyperbaric oxygen therapy | Medical use of oxygen at a level higher than atmospheric pressure. This helps fight bacteria and infection |

| Hypoxia | Insufficient levels of oxygen in blood or tissue |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) | Administration of antibodies through the veins |

| Motricity | Strength in upper and lower extremities after disease |

| Morbidity | Disability or degree that the health condition affects the patient |

| Mortality | Death rate |

| MRSA | Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| Myonecrosis | The destruction or death of muscle tissue |

| Necrosis | Death of body tissue |

| Obliterating endarteritis | Severe proliferating endarteritis (inflammation of the inner lining of an artery) that results in an occlusion of the lumen (the space inside a tubular structure) of the smaller vessels |

| Person‐years | Unit of measurement used to estimate rate of a disease during a defined period of observation |

| Polymicrobial | Polymicrobial infection is caused by several species of micro‐organisms |

| Subcutaneous tissue | Layer of tissue below the epidermis and the dermis of the skin. It is also called the hypodermis |

| Synergistic combination | Additive effects of bacterial agents |

| Synergistic gangrenes | Necrotizing soft tissue infection caused by a mix of bacteria (usually a mix of anaerobic and aerobic micro‐organisms) |

| Systemic | Affecting the entire body |

| Third‐generation quinolones | The quinolones are a family of synthetic broad‐spectrum antibiotic drugs |

| Thrombi | A blood clot inside a blood vessel |

| Transmissible agents | Infectious pathogens that can be transmitted |

| Vasopressors | Any medication that induces vasoconstriction of blood vessels to raise reduced blood pressure |

| Vimentin | A protein, the expression of which is increased after skeletal muscle injury |

| Incidence of necrotizing fasciitis | ||||

| Authors | Period of study | Country | Pathology | Incidence |

| Kaul R et al (Kaul 1997) | 1991 | Canada | GAS NF | 0.085 per 100,000 p‐y |

| 1995 | 0.4 per 100,000 p‐y | |||

| Ellis Simonsen et al (Ellis Simonsen 2006) | January 1997 to December 2002 | United States | NF | 0.04 per 1000 p‐y |

| O'Grady et al (O'Grady 2007) | March 2002 to August 2004 | Australia | IGAS | 2.7 per 100,000 p‐y (10.9% of NF) |

| Lamagni et al (Lamagni 2008) | January 2003 to December 2004 | Europe | IGAS | 2.37 per 100,000 p‐y (8% of NF) |

| Lepoutre et al (Lepoutre 2011) | November 2006 to November 2007 | France | IGAS | 3.1 per 100,000 p‐y (18% of NF) |

| GAS NF:group A streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis; IGAS: invasive group A streptococcal disease; NF: necrotizing fasciitis; p‐y: person‐years | ||||

| Study | Contact | Requested information | Contacted | Reply (last check 23 April 2017) |

| Darenberg 2003 (awaiting classification study) | Dr Norrby‐Teglund | Outcomes in the specific subgroup of patients with NSTI: ‐Mortality at day 30, ‐Proportion of patients with serious adverse events ‐Survival time ‐Patients with alteration of 25% of Functional Impairment Scale (%) | July 28, 2015 September 07, 2015 | No response |

| Tally 1986 (awaiting classification study) | Dr Kellum | Outcomes in the specific subgroup of patients with NSTI: ‐Mortality at day 30, ‐Proportion of patients with serious adverse events ‐Survival time ‐Patients with alteration of 25% of Functional Impairment Scale (%) | July 24, 2015 September 07, 2015 | No response |

| Vick‐Fragoso 2009 (included study) | Dr Bogner, Dr Petri | Outcomes in the specific subgroup of patients with NSTI: ‐Mortality at day 30, ‐Proportion of patients with serious adverse events ‐Survival time ‐Patients with alteration of 25% of Functional Impairment Scale (%) | September 07, 2015 | Additional data to the publication provided for mortality, proportion of patients with serious adverse events and survival time. Outcome data for assessment of long term morbidity not provide |

| Bulger 2014 (included study) | Dr Bulger | Outcomes: ‐Survival time ‐Patients with alteration of 25% of Functional Impairment Scale (%) | September 07, 2015 September 09, 2015 | Outcome data not provided |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Mortality within 30 days Show forest plot | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.39, 23.07] |

| 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events Show forest plot | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.30, 1.31] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Mortality within 30 days Show forest plot | 1 | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.05, 2.16] |

| 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events Show forest plot | 1 | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.49 [0.52, 4.27] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Mortality within 30 days Show forest plot | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.42, 3.23] |

| 2 Proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events Show forest plot | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.32, 1.65] |