مداخلات دارویی در مدیریت درمانی کلانژیت اسکلروزان اولیه

Referencias

منابع مطالعات واردشده در این مرور

منابع مطالعات خارجشده از این مرور

منابع مطالعات در انتظار ارزیابی

منابع مطالعات در حال انجام

منابع اضافی

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: UK. Ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 3 months after completion of 2‐week treatment. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Mortality. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out: "technical failures":

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were randomised by sealed envelope to receive continuous nasobiliary irrigation with either normal saline alone or normal saline plus hydrocortisone. [.] The randomisation code was blocked to ensure an approximately equal number of patients in each group at any stage of the trial". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were randomised by sealed envelope". Comment: "Opaque sealed envelopes manually shuffled" (trial author's reply). |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients and interpreters blinded to allocation" (trial author's reply). |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients and interpreters blinded to allocation" (trial author's reply). |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality and liver transplantation were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Low risk | Comment: "Patients were cared for and followed within normal NHS founded hospital stay. No additional grants were sought" (trial author's reply). |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: UK. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: not stated. Follow‐up: 12 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial". Comment: Further details were not available. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; no outcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Germany. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 12 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Patients were assigned with a computer generated block randomisation to receive UDCA or identical‐appearing placebo". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The study was a double‐blind, randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of UDCA with that of placebo treatment…… Patients were assigned with a computer generated block randomization to receive UDCA or identical appearing placebo". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The study was a double‐blind, randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of UDCA with that of placebo treatment…… Patients were assigned with a computer generated block randomization to receive UDCA or identical appearing placebo". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Two patients (1 for each group) were excluded from the analysis (withdrawal), but adverse events were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; no outcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Patients were assigned with a computer generated block randomization to receive UDCA or identical appearing placebo in 250‐mg capsules (13 to 15 mg/kg body wt/day; provided by Dr. Falk GmbH, Frei‐burg, Germany)". Comment: The trial was funded by a party with a vested interest in the results. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: UK/Germany. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 24 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups. Group 3: high‐dose UDCA (30 mg/kg/d) over the period of follow‐up of the study (n = 9). | |

| Outcomes | 1. Number of any type of adverse events. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "This randomisation was carried out by an independent blinded trial pharmacist in each centre using a predetermined randomisation scheme. Patient numbers were issued sequentially within a centre". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "This randomisation was carried out by an independent blinded trial pharmacist in each centre using a predetermined randomisation scheme. Patient numbers were issued sequentially within a centre". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A proportion of the capsules taken by patients in the low and standard dose arms of the trials were placebos. The trial was a randomised, double blinded, dose‐finding study". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A proportion of the capsules taken by patients in the low and standard dose arms of the trials were placebos. The trial was a randomised, double blinded, dose‐finding study". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality was not reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Dr. Falk Pharma (Freiburg, Germany) provided drugs and placebos for this trial as well as financial support for the statistical calculations performed at ClinResearch (Koln, Germany), an independent institute for biostatistics of clinical trials". Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: not stated. Follow‐up: 24 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups. Group 3: no active intervention (n = 20). | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported. | |

| Notes | "No statistical differences in the various outcome measures for the colchicine and the untreated group were evident after 2 years of follow‐up. As a result, these data were collapsed as a single controlled group (n = 39) and were compared against the UDCA group (n = 20)". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Comment: A group of participants received no treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; no outcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Finland. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 36 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. Group 2: low‐dose UDCA (15 mg/kg/d) and metronidazole 600 to 800 mg/d over the period of follow‐up of the study (n = 34). | |

| Outcomes | 1. Number of any type of adverse events. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was done centrally with computer generated blocks". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was done centrally with computer generated blocks". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "In this multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, the patients were randomized either to UDCA and placebo (n = 41) or UDCA and MTZ (n = 39)". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "In this multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, the patients were randomized either to UDCA and placebo (n = 41) or UDCA and MTZ (n = 39). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography findings were analysed by two radiologists independently, specialised in hepatobiliary disease, and blinded to clinical data and the order of examinations". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality was not reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Mary and Georg C. Ehnrooth Foundation. Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results: Orion Pharma produces metronidazole, and Leiras produces UDCA. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: The Netherlands. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 13 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. Group 2: placebo at weeks 0, 2, 6, 12, 18, and 24 (n = 3). | |

| Outcomes | 1. Proportion of participants with severe adverse events | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were randomised in a 2:1 ratio to receive infliximab or placebo at weeks 0, 2, 6,12, 18, and 24". Comment: Additional details were not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Infliximab was supplied in 20‐mL vials containing 100mg of the lyophilized concentrate; placebo was identically formulated. The infusion solution was administered by blinded investigators using an infusion set". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Infliximab was supplied in 20‐mL vials containing 100mg of the lyophilized concentrate; placebo was identically formulated. The infusion solution was administered by blinded investigators using an infusion set". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality was not reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Daan Hommes has served as consultant and speaker for both Centocor and Schering Plough. Supported by a Research Grant from Centocor, Inc (Malvern, USA)". Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results (this company produces infliximab). |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 48 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. Group 2: identical placebo for 24 months (n = 10). | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "The code was broken on patients who were judged to be treatment failures". Comment: Additional details were not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A double‐blind controlled trial of oral‐pulse methotrexate therapy in the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis.…Methotrexate (or placebo) was administered orally each week in three divided doses of 5 mg every 12 hours (15 mg/wk) for 2 years in a double‐blind manner. Identical methotrexate and placebo tablets were kindly provided by Lederle laboratories". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A double‐blind controlled trial of oral‐pulse methotrexate therapy in the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis.Methotrexate (or placebo) was administered orally each week in three divided doses of 5 mg every 12 hours (15 mg/wk) for 2 years in a double‐blind manner. Identical methotrexate and placebo tablets were kindly provided by Lederle laboratories". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; no outcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Identical methotrexate and placebo tablets were kindly provided by Lederle laboratories..Supported by General Research Center grant MOlRR00054 from the National Institutes of Health and Lederle Laboratories, Pearl River, New York". Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 36 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. Group 2: placebo over the period of follow‐up of the study (n = 31). | |

| Outcomes | 1. Mortality. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "We initiated in 1980 a randomized double‐blind trial of penicillamine versus placebo. Patients were randomly assigned to drug or placebo groups. Randomization was weighted in favour of the drug group in anticipation of possible drug toxicity requiring severance from the study. Penicillamine and placebo (furnished to us through the courtesy of Merck Sharp & Dohme, West Point, Pa.) were dispensed in identical yellow capsules by one pharmacist". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "We initiated in 1980 a randomized double‐blind trial of penicillamine versus placebo. Patients were randomly assigned to drug or placebo groups. Randomization was weighted in favour of the drug group in anticipation of possible drug toxicity requiring severance from the study. Penicillamine and placebo (furnished to us through the courtesy of Merck Sharp & Dohme, West Point, Pa.) were dispensed in identical yellow capsules by one pharmacist". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality and liver transplantation were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "This work was supported by the Mayo Foundation, by a grant‐in‐aid from Merck Sharp & Dohme Research Laboratories and in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (RR585)". Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: mean follow‐up 27 months (minimum 3 months). | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. Group 2: identical‐appearing placebo over the period of follow‐up of the study (n = 51). | |

| Outcomes | Time to liver transplantation. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was carried out separately for each of the eight strata (combination of variables) with a computer generated, blocked, randomised drug/assignment schedule. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The patients, physicians, nurses and study coordinators were blinded as to whether active drug or placebo was being administrated". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The patients, physicians, nurses and study coordinators were blinded as to whether active drug or placebo was being administrated". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality was not reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Supported in part by Axcan Pharma (produces UDCA)". Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: planned 60 months, but study stopped earlier owing to futility. Only 50 participants had a cholangiography at 60 months. Biochemical follow‐up. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Mortality. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Computer‐based dynamic allocation used to assign patients to study groups via the coordinating centre in Rochester, MN". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Computer‐based dynamic allocation used to assign patients to study groups via the coordinating centre in Rochester, MN". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The physician, study coordinator, and patient were blinded as to whether active drug or placebo was being administered". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The physician, study coordinator, and patient were blinded as to whether active drug or placebo was being administered". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: All randomised participants were included in the group to which they were allocated (i.e. intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality and liver transplantation were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney diseases Grant 56924 and Axcan Pharma (produces UDCA) as well as well as Grant M01RR00065 from the National Center for Research resources." Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: UK. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no.

Exclusion criteria: not stated. Follow‐up: 24 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; no outcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: UK/Germany. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no.

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 24 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "This preliminary study was designed as a double blind, randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of UDCA with that of placebo treatment….The placebo was an identical‐appearing capsule administered in the same quantity and manner". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "This preliminary study was designed as a double blind, randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of UDCA with that of placebo treatment. . .The placebo was an identical‐appearing capsule administered in the same quantity and manner". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote:"Patients who were lost to follow‐up or died during the study period were included in the final analysis, provided that at least one set of follow‐up data was available". Comment: No post‐randomisation drop‐outs were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; nooutcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Sweden. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: not stated. Follow‐up: 36 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Mortality. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "The randomization procedure was performed for each center using the sealed envelope technique". Comment: Further information on sealed envelope technique is not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "The randomization procedure was performed for each center using the sealed envelope technique". Comment: Further information on sealed envelope technique is not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The results of a double‐blind, randomized, controlled study comparing colchicine with placebo for 36 months in 84 patients with PSC are reported. After giving informed consent, the patients in each center were randomized to receive 1 mg colchicine daily or a placebo identical in appearance". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The results of a double‐blind, randomized, controlled study comparing colchicine with placebo for 36 months in 84 patients with PSC are reported. After giving informed consent, the patients in each center were randomized to receive 1 mg colchicine daily or a placebo identical in appearance". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality and liver transplant were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Sweden/Norway. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 60 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Mortality. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The trial code was kept at the pharmacies in the hospitals. The code was not broken until data from all patients had been collected". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "We conducted a randomized, double‐blind, placebo controlled, multicenter….At that time we had recruited 219 patients (121 from Sweden, 77 from Norway, and 21 from Denmark) who were randomized to either UDCA (in a daily dose of 17–23 mg/kg of body weight divided in 2 doses) or placebo in identical 250‐mg gelatin capsules containing microcrystalline cellulose". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "We conducted a randomized, double‐blind, placebo controlled, multicenter….At that time we had recruited 219 patients (121 from Sweden, 77 from Norway, and 21 from Denmark) who were randomized to either UDCA (in a daily dose of 17–23 mg/kg of body weight divided in 2 doses) or placebo in identical 250‐mg gelatin capsules containing microcrystalline cellulose". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality and liver transplant were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Supported by Dr Falk Pharma GmbH". Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results (this company produces UDCA). |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Iran. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 12 weeks after 12 weeks of treatment. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes |

| |

| Notes | Trial authors provided additional information on outcomes in February 2017. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "An independent investigator who was blinded to the treatment group made random allocation cards by using computer‐generated random numbers". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Another investigator who was also blinded was responsible for the patients’ enrolments and data collection". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "We used the triple blinding method which meant that patients, investigators who were responsible for the patients’ enrolment and the analyzer of the data at the end of the study were unaware of identities to reduce the chance of bias occurrence in the study". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "We used the triple blinding method which meant that patients, investigators who were responsible for the patients’ enrolment and the analyzer of the data at the end of the study were unaware of identities to reduce the chance of bias occurrence in the study". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: No post‐randomisation drop‐outs were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality and morbidity were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Low risk | Quote: "This study was supported by a grant from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences". |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Cross‐over randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Denmark. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: not stated. Follow‐up: 24 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported before cross‐over. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Trial authors stated double‐blind and have used placebo. However, the groups blinded were not reported. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Trial authors stated double‐blind and have used placebo. However, the groups blinded were not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; no outcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: yes. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: final analysis performed after mean follow‐up of 34 months in the placebo group and 36 months in the cyclosporin group. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Numbers of any types of adverse events. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "From 27 June 1985 to 13 July 1988, 35 patients with precirrhotic primary sclerosing cholangitis were randomly allocated to receive low dose cyclosporin (initial dose 5 mg/kg/day) or placebo in a double blind trial". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "From 27 June 1985 to 13 July 1988, 35 patients with precirrhotic primary sclerosing cholangitis were randomly allocated to receive low dose cyclosporin (initial dose 5 mg/kg/day) or placebo in a double blind trial". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality was not reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Supported by grants from the Sandoz Corporation and the Mayo Foundation". Comment: The trial was funded by parties with vested interest in the results. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 24 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Concealed randomisation via investigational pharmacy or by concealed envelopes" (study author's reply). |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: "Neither patient nor investigator was blinded to study medication". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: "Neither patient nor investigator was blinded to study medication". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "All data were analysed by the intention‐to‐treat method". Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; no outcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Supported in part by a NIH grant to the General Clinical Research Center of Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, M01‐RR‐00065‐35 and by the generous support of Roche Laboratory, Nutley, NJ and Axcan Scandipharm, Birmingham, AL, USA". Comment: The trial was funded by a party with vested interest in the results (Roche produces mycophenolate mofetil). |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Germany. Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria: not stated. Exclusion criteria: not stated. Follow‐up: unclear: definitive analysis planned for 12 months and interim analysis at 3 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups. | |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest were reported. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post randomisation drop‐out not reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; no outcomes of interest were reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Females: 14 (40%). Separate data for the subgroup with ulcerative colitis: no. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 groups. Group 1: vancomycin 125 or 250 mg orally 4 times a day for 12 weeks (n = 15). Group 2: metronidazole 250 or 500 mg orally 3 times a day for 12 weeks (n = 13). | |

| Outcomes | Numbers of any types of adverse events. | |

| Notes | Reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐out:

| |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Drugs were packaged in identical gelatin capsules, and patients and investigators were blinded to the type and dose of the drug". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Drugs were packaged in identical gelatin capsules, and patients and investigators were blinded to the type and dose of the drug". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: Post‐randomisation drop‐outs may be related to the treatment that participants received. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality was not reported. |

| For‐profit bias | Low risk | Quote: "Funded by the PSC Partners Seeking a Cure 2009–2010 Research Grant". |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: international, multi‐centric. Inclusion criteria:

Follow‐up: 4 weeks after 12 weeks of treatment. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to 4 groups. | |

| Outcomes | 1. Serious adverse events. | |

| Notes | Given that the number of participants in each group was not reported, it was not possible to include this trial in the analysis. The proportion of serious adverse events was not reported so that we could report this information in a narrative manner. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Placebo was used, but blinding was not mentioned. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: Placebo was used, but blinding was not mentioned. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: No published protocol was available; mortality was not reported. |

| For‐profit bias | High risk | Quote: "Employment: Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH". |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias. |

AMA = antimitochondrial antibody; PSC = primary sclerosing cholangitis; UDCA = ursodeoxycholic acid

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Not a RCT (comments on Lindor 1997). | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| Editorial on Lindor 2009. | |

| Not an RCT. | |

| Comment on a non‐RCT. | |

| Comment on a non‐RCT. | |

| Comment on a non‐RCT. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| The study includes transplanted patients. | |

| Not an RCT. | |

| No separate data for participants with primary sclerosing cholangitis. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| Comment on an included trial (Sterling 2004). | |

| Not an RCT. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| Review, not a RCT. | |

| No separate data for participants with primary sclerosing cholangitis. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| Comments on Beuers 1992 and other published experiences. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| All participants received the same treatment (UDCA) for 1 year before the randomised period (UDCA and placebo groups). | |

| Review, not a RCT. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| Not a RCT. | |

| No separate data for participants with primary sclerosing cholangitis. | |

| Comment on an excluded study (Imam 2011). | |

| No separate data for participants with primary sclerosing cholangitis. | |

| No comparison between different treatments: Participants in both arms received the same dose of UDCA once a day or in divided doses. | |

| In this RCT, participants received different types and doses of steroids in combination with UDCA. | |

| Control group received colchicine or no treatment, and no separate data were available for participants who received no treatment. | |

| No separate data for participants with primary sclerosing cholangitis. | |

| Treatment was not targeted at improving outcomes related to primary sclerosing cholangitis. | |

| No pharmacological agents were studied. | |

| Not a RCT. |

RCT = randomised clinical trial; UDCA = ursodeoxycholic acid

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Awaiting full text. |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes |

| Methods | Randomised, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | Trial of low‐dose, medium‐dose, and high‐dose ursodeoxycholic acid with placebo in primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Outcomes | Not available. |

| Notes | Recruitment status: completed. |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | High‐dose UDCA (28‐30 mg/kg/d) vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | Cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, cholangiocarcinoma, liver transplantation, quality of life, and mortality. |

| Notes | Recruitment status: completed. |

UDCA = ursodeoxycholic acid

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | EUCTR2012‐004170‐26‐IT. |

| Methods | Randomised double‐blinded placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | N‐acetylcysteine 600 mg vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | Quality of life. |

| Starting date | Not stated. |

| Contact information | |

| Notes | Not recruiting. |

| Trial name or title | UDCAPSCSURV. |

| Methods | Phase 3, open‐label, randomised, prospective clinical trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | 17‐23 mg/kg/d UDCA vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | Decompensated liver cirrhosis and liver transplantation. |

| Starting date | Not stated. |

| Contact information | hanns‐[email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | EUCTR2015‐003392‐30‐GB. |

| Methods | Phase 2, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group, multiple‐centre study. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | NGM282 vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest for this review. |

| Starting date | Not stated. |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | NCT01672853. |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | GS‐6624, a monoclonal antibody against Lysyl Oxidase Like 2 (LOXL2), vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | Adverse events. |

| Starting date | February 2013. |

| Contact information | Rob Myers, M.D. Gilead Sciences. |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | NCT01688024. |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | Mitomycin C vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | Adverse events. |

| Starting date | September 2012. |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | NCT01755507. |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | Norursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | Adverse events. |

| Starting date | December 2012. |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | NCT02177136. |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | Obeticholic acid vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | Adverse events. |

| Starting date | December 2014. |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | NCT02704364. |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | NGM282 vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest for this review. |

| Starting date | February 2016. |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | NCT02943460. |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | GS‐9674 vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | Adverse events. |

| Starting date | November 2016. |

| Contact information | GS‐US‐428‐[email protected] |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | NCT03035058. |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. |

| Participants | Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. |

| Interventions | Vedolizumab vs placebo. |

| Outcomes | No outcomes of interest for this review. |

| Starting date | February 2017. |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

vs = versus

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Mortality at maximal follow‐up Show forest plot | 6 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 1 Mortality at maximal follow‐up. | ||||

| 1.1 Colchicine vs placebo | 1 | 84 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.04, 5.07] |

| 1.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | 70 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.39, 3.58] |

| 1.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | 11 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.10, 90.96] |

| 1.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 2 | 348 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [0.63, 3.63] |

| 1.5 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | 29 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

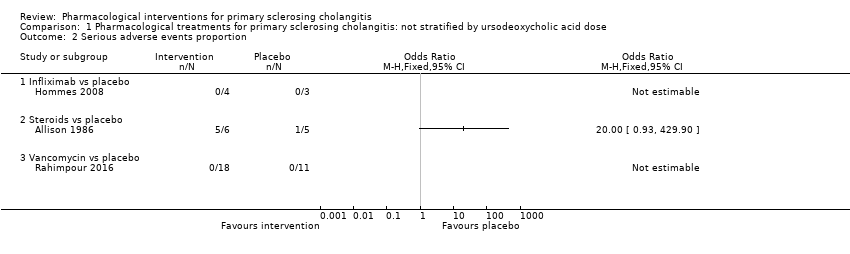

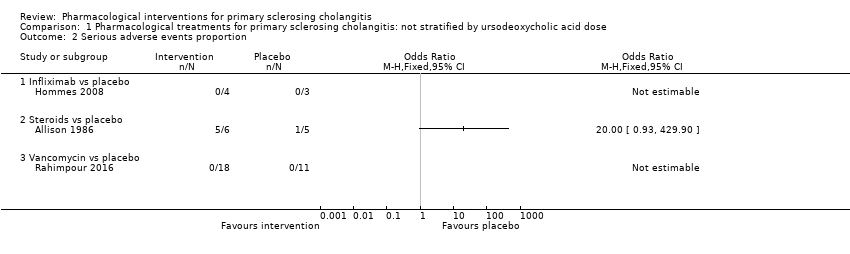

| 2 Serious adverse events proportion Show forest plot | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 2 Serious adverse events proportion. | ||||

| 2.1 Infliximab vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

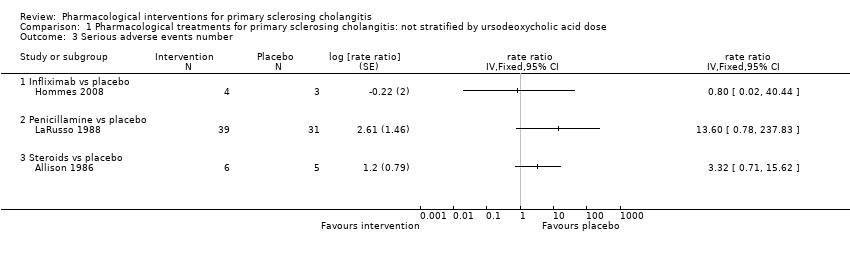

| 3 Serious adverse events number Show forest plot | 3 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 3 Serious adverse events number. | ||||

| 3.1 Infliximab vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

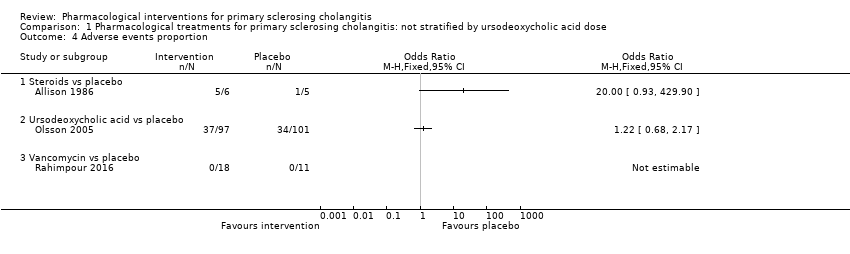

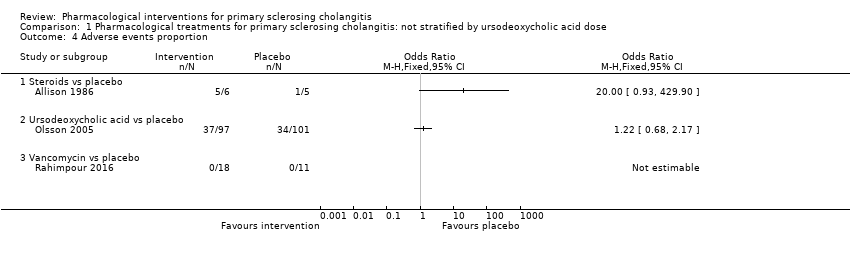

| 4 Adverse events proportion Show forest plot | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 4 Adverse events proportion. | ||||

| 4.1 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

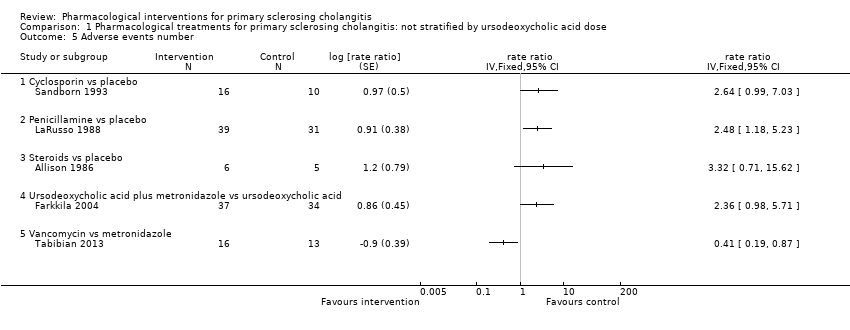

| 5 Adverse events number Show forest plot | 5 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 5 Adverse events number. | ||||

| 5.1 Cyclosporin vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid plus metronidazole vs ursodeoxycholic acid | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.5 Vancomycin vs metronidazole | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Quality of life Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 1.6  Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 6 Quality of life. | ||||

| 6.1 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Liver transplantation Show forest plot | 7 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.7  Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 7 Liver transplantation. | ||||

| 7.1 Colchicine vs placebo | 1 | 84 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.09, 3.71] |

| 7.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | 70 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.32, 4.01] |

| 7.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | 11 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 2 | 348 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.52, 1.81] |

| 7.5 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | 29 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.6 Ursodeoxycholic acid plus metronidazole vs ursodeoxycholic acid | 1 | 71 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.03, 2.90] |

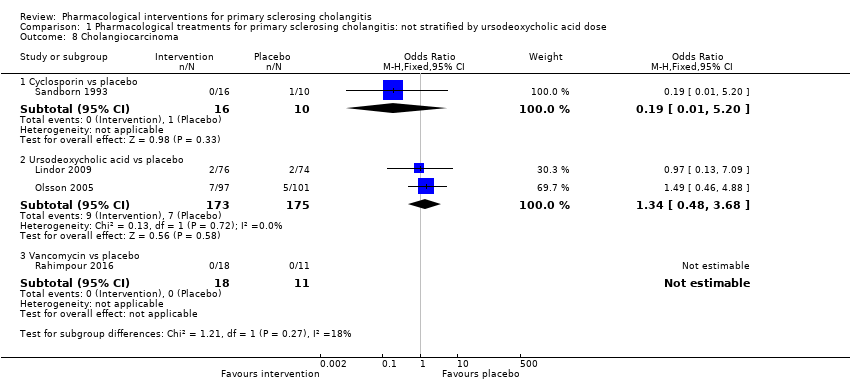

| 8 Cholangiocarcinoma Show forest plot | 4 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.8  Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 8 Cholangiocarcinoma. | ||||

| 8.1 Cyclosporin vs placebo | 1 | 26 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.01, 5.20] |

| 8.2 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 2 | 348 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.48, 3.68] |

| 8.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | 29 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

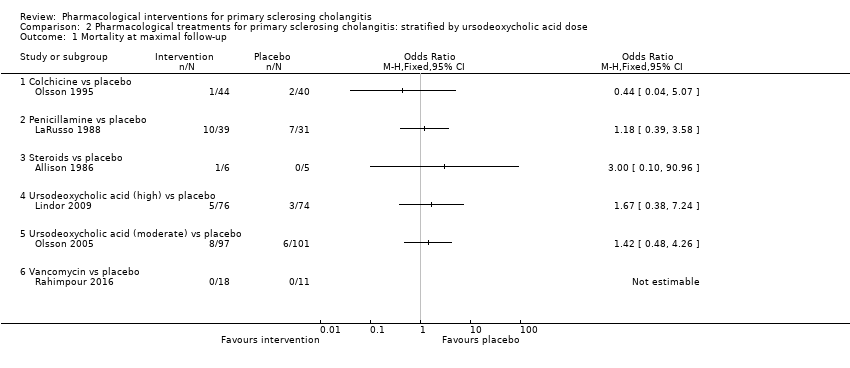

| 1 Mortality at maximal follow‐up Show forest plot | 6 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 1 Mortality at maximal follow‐up. | ||||

| 1.1 Colchicine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.6 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Serious adverse events proportion Show forest plot | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.2  Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 2 Serious adverse events proportion. | ||||

| 2.1 Infliximab vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

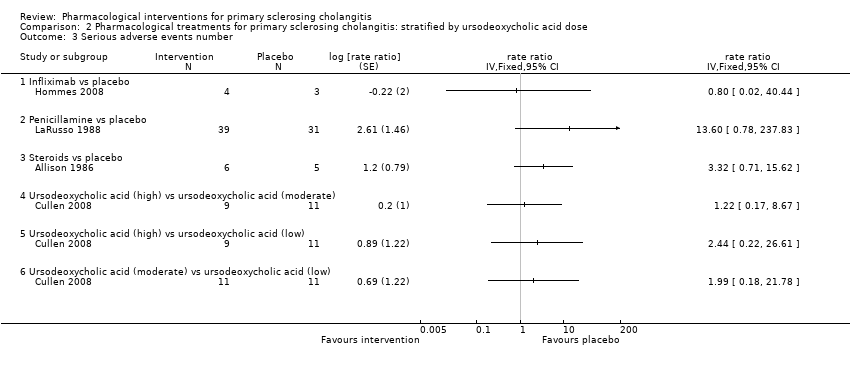

| 3 Serious adverse events number Show forest plot | 4 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.3  Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 3 Serious adverse events number. | ||||

| 3.1 Infliximab vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.5 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.6 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Adverse events proportion Show forest plot | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.4  Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 4 Adverse events proportion. | ||||

| 4.1 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

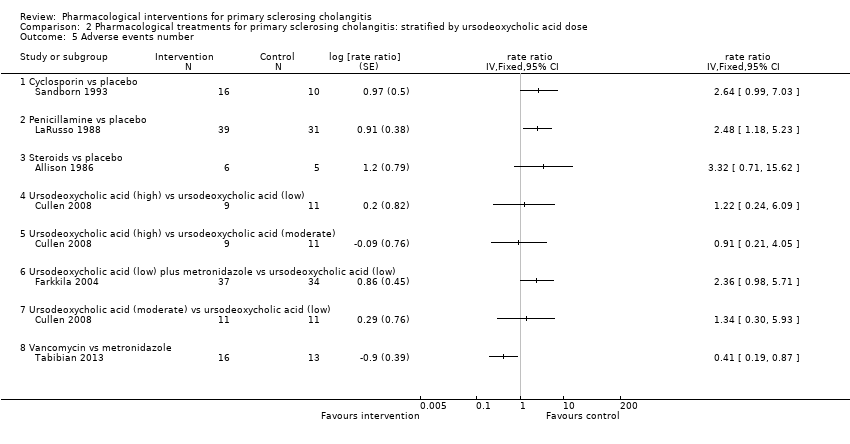

| 5 Adverse events number Show forest plot | 6 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.5  Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 5 Adverse events number. | ||||

| 5.1 Cyclosporin vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.5 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.6 Ursodeoxycholic acid (low) plus metronidazole vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.7 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.8 Vancomycin vs metronidazole | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Quality of life Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.6  Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 6 Quality of life. | ||||

| 6.1 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs placebo | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Liver transplantation Show forest plot | 8 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.7  Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 7 Liver transplantation. | ||||

| 7.1 Colchicine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.5 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.6 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.7 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.8 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.9 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.10 Ursodeoxycholic acid (low) plus metronidazole vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8 Cholangiocarcinoma Show forest plot | 4 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 2.8  Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 8 Cholangiocarcinoma. | ||||

| 8.1 Cyclosporin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.2 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.3 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.4 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

Study flow diagram.

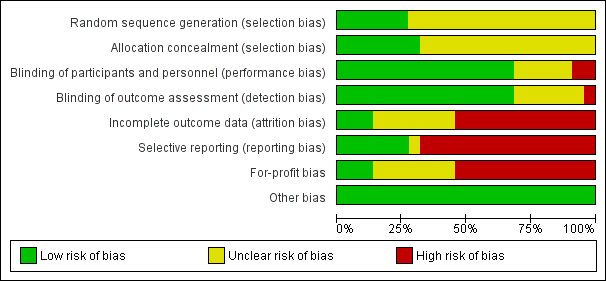

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Based on an alpha error of 2.5%, power of 90% (beta error of 10%), relative risk reduction (RRR) of 20%, control group proportion observed in the trials (Pc), and heterogeneity observed in the analyses, only a small fraction of the diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS) has been reached (required information size = 348; DARIS = 14,509 for mortality at maximal follow‐up; required information size = 348; DARIS = 35,846 for liver transplantation; required information size = 348; DARIS = 29,191 for cholangiocarcinoma), and trial sequential monitoring boundaries were not drawn. The Z‐curves (blue lines) do not cross conventional boundaries (dotted green lines). This indicates high risk of random errors for all outcomes included in this review.

Network plot for mortality at maximal follow‐up. The size of the node (circle) provides a measure of the number of trials in which the particular treatment was included in one of the arms. The thickness of the line provides a measure of the number of direct comparisons between two nodes (treatments).

Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 1 Mortality at maximal follow‐up.

Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 2 Serious adverse events proportion.

Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 3 Serious adverse events number.

Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 4 Adverse events proportion.

Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 5 Adverse events number.

Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 6 Quality of life.

Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 7 Liver transplantation.

Comparison 1 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: not stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 8 Cholangiocarcinoma.

Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 1 Mortality at maximal follow‐up.

Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 2 Serious adverse events proportion.

Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 3 Serious adverse events number.

Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 4 Adverse events proportion.

Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 5 Adverse events number.

Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 6 Quality of life.

Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 7 Liver transplantation.

Comparison 2 Pharmacological treatments for primary sclerosing cholangitis: stratified by ursodeoxycholic acid dose, Outcome 8 Cholangiocarcinoma.

| Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo for primary sclerosing cholangitis | |||||

| Patient or population: people with primary sclerosing cholangitis | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | Number of participants | Quality of the evidence | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Placebo | Ursodeoxycholic acid | ||||

| Mortality Follow‐up: 60 months | 72 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 | OR 1.51 | 348 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

| Serious adverse events | No trials reported the number of participants with serious adverse events or numbers of serious adverse events. | ||||

| Proportion of people with adverse events Follow‐up: 60 months | 337 per 1000 | 358 per 1000 | OR 1.22 | 198 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

| Number of adverse events | No trials reported the number of adverse events. | ||||

| Health‐related quality of life Follow‐up: 5 years Scale: SF‐36 General Health Scale (Limits: 0 to 100; higher = better) | Mean in the placebo group was 61.10. | Mean in the ursodeoxycholic acid group was 1.30 higher (5.61 lower or 8.21 higher). | ‐ | 198 (1 trial) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

| Liver transplantation Follow‐up: 60 months | 123 per 1000 | 120 per 1000 | OR 0.97 | 348 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

| Any malignancy | No trials reported this outcome. | ||||

| Cholangiocarcinoma Follow‐up: 60 months | 43 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 | OR 1.34 | 348 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

| Colorectal cancer | No trials reported this outcome. | ||||

| Cholecystectomy | No trials reported this outcome. | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the mean control group proportion. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| 1 Downgraded one level for risk of bias: the trial(s) were at high risk of bias. | |||||

| Study name | Number of people in intervention group | Number of people in control group | Risk of bias | Overall risk of bias | ||||||

| Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Vested interest bias | ||||

| Colchicine vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 44 | 40 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | |

| Cyclosporin vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 16 | 10 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | |

| Infliximab vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 4 | 3 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | |

| Methotrexate vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 11 | 10 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | |

| 5 (crossed over after 1 year) | 8 (crossed over after 1 year) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | |

| NorUrsodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | ||||||||||

| Not stated | Not stated | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | High | |

| Penicillamine vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 39 | 31 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | High | High | |

| Steroids vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 6 | 5 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High | High | Low | High | |

| UDCA (high) vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 76 | 74 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High | High | |

| UDCA (moderate) vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 11 | 11 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | High | |

| 13 | 13 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High | Unclear | High | |

| 97 | 101 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | High | High | |

| UDCA (low) vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 6 | 8 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | High | High | High | |

| 51 | 51 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | |

| 7 | 7 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | High | |

| 6 | 6 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | High | |

| UDCA (low) vs UDCA (moderate) vs UDCA (high) | ||||||||||

| 11 | 11 (UDCA (moderate)) and 9 (UDCA (high)) | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | |

| UDCA (low) vs colchicine vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 20 | 19 (colchicine) and 20 (placebo) | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | |

| UDCA (low) plus metronidazole vs UDCA (low) | ||||||||||

| 37 | 34 | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High | High | High | |

| UDCA (low) plus mycophenolate vs UDCA (low) | ||||||||||

| 6 | 10 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | High | High | High | |

| Vancomycin vs metronidazole | ||||||||||

| 16 | 13 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High | High | Low | High | |

| Vancomycin vs placebo | ||||||||||

| 18 | 11 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | High | |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Mortality at maximal follow‐up Show forest plot | 6 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Colchicine vs placebo | 1 | 84 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.04, 5.07] |

| 1.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | 70 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.39, 3.58] |

| 1.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | 11 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.10, 90.96] |

| 1.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 2 | 348 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [0.63, 3.63] |

| 1.5 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | 29 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Serious adverse events proportion Show forest plot | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Infliximab vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Serious adverse events number Show forest plot | 3 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Infliximab vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Adverse events proportion Show forest plot | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Adverse events number Show forest plot | 5 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Cyclosporin vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid plus metronidazole vs ursodeoxycholic acid | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.5 Vancomycin vs metronidazole | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Quality of life Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Liver transplantation Show forest plot | 7 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Colchicine vs placebo | 1 | 84 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.09, 3.71] |

| 7.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | 70 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.32, 4.01] |

| 7.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | 11 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 2 | 348 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.52, 1.81] |

| 7.5 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | 29 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.6 Ursodeoxycholic acid plus metronidazole vs ursodeoxycholic acid | 1 | 71 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.03, 2.90] |

| 8 Cholangiocarcinoma Show forest plot | 4 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Cyclosporin vs placebo | 1 | 26 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.01, 5.20] |

| 8.2 Ursodeoxycholic acid vs placebo | 2 | 348 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.48, 3.68] |

| 8.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | 29 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Mortality at maximal follow‐up Show forest plot | 6 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Colchicine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.6 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Serious adverse events proportion Show forest plot | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Infliximab vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Serious adverse events number Show forest plot | 4 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Infliximab vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.5 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.6 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Adverse events proportion Show forest plot | 3 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Vancomycin vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Adverse events number Show forest plot | 6 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Cyclosporin vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Steroids vs placebo | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.4 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.5 Ursodeoxycholic acid (high) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.6 Ursodeoxycholic acid (low) plus metronidazole vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.7 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs ursodeoxycholic acid (low) | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.8 Vancomycin vs metronidazole | 1 | rate ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Quality of life Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Ursodeoxycholic acid (moderate) vs placebo | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Liver transplantation Show forest plot | 8 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7.1 Colchicine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.2 Penicillamine vs placebo | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |