Intervenções comunitárias e nos sistemas de saúde para melhorar o comparecimento ao pré‐natal e resultados de saúde

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Parallel arm cluster‐RCT conducted at 18 sites in Bangladesh between Feb 2005 and Dec 2008. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 18 clusters (6389 women). Clusters: purposive sampling was performed in 3 different divisions in Bangladesh on the basis of the districts having active Diabetic Association of Bangladesh (BADAS) offices. Within these districts, sub districts (upazilas) and unions (the lowest level administrative units in rural Bangladesh) were also purposefully sampled by use of recommendations from BADAS representatives, the main criteria being perceived limited access to perinatal health care in those unions, and a feasible travelling distance from BADAS district headquarters. Individuals: women were eligible to participate in the study if they were aged 15–49 years, residing in the project area, and had given birth during the study period. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (re‐organisation of health services intervention) and community (education or IEC intervention). Arm 1 (9 clusters, 17,514 births ITT): in intervention clusters, a facilitator convened 18 groups every month to support participatory action and learning for women, and to develop and implement strategies to address maternal and neonatal health problems. 5 of the 9 clusters became TBA intervention clusters and 4 became controls. 482 TBAs were given basic training in undertaking clean and safe deliveries, providing safe delivery kits, recognising danger signs in mothers and infants, making emergency preparedness plans, accompanying women to facilities, and undertaking mouth‐to‐mouth resuscitation. They also received additional training in neonatal resuscitation with bag valve‐mask. Arm 2 (9 clusters, 18,599 births ITT): health services strengthening intervention and basic training of TBAs. | |

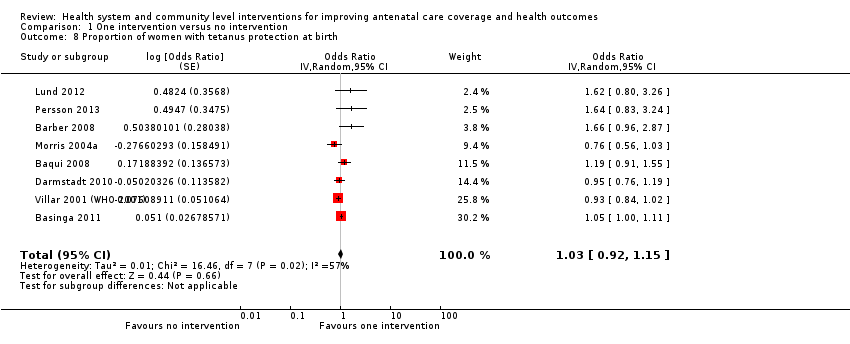

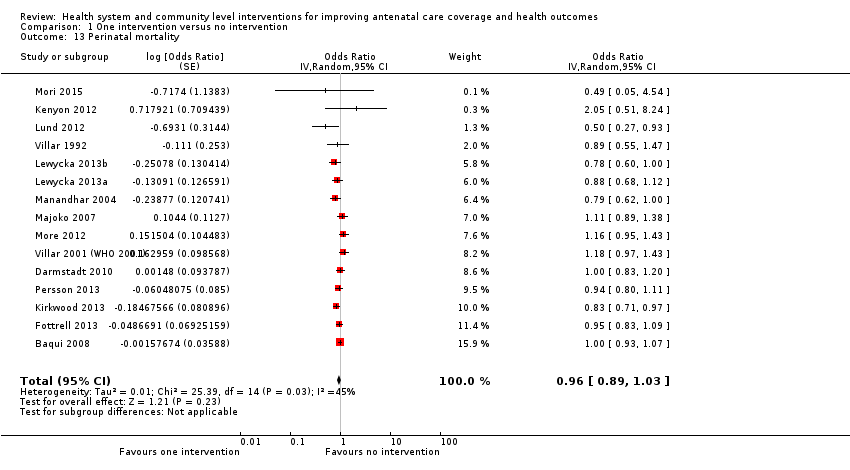

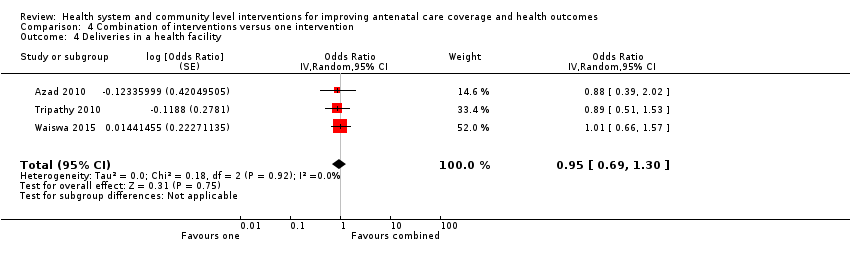

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: neonatal mortality rate. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits), maternal mortality. Secondary: health facility deliveries, tetanus protection, perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality. We have used mortality data from Table 2 (Azad 2010 p. 1197). We used Years 1‐3 combined, excluding the "temporary and tea garden residents" who may not have received the full intervention. We calculated our own cluster adjusted ORs for antenatal care outcomes using the percentages from Table 4, p. 1200 and the denominators from years 1‐3 in Table 2, p. 1197 (all births: intervention n = 15,696 and control n = 15,257). | |

| Notes | Funders: Women and Children First, the UK Big Lottery Fund, Saving Newborn Lives, and the UK Department for International Development. | |

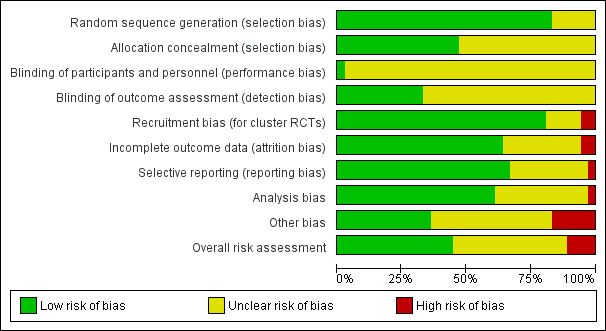

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "The allocation sequence was decided upon by the project team before drawing" pg 1194 "and was based on clusters rather than |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clear how allocation was concealed. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Unclear risk | "Additionally, about 10% of mothers in our study area were temporary residents and mainly came into the cluster areas to give birth, since the tradition is for women to go to their mothers’ home just before delivery. These temporary residents were not exposed to the women’s group intervention, and often had returned to their marital homes outside the study area before the postnatal interview." Presumably this would have affected all clusters. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Most relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; ICC reported; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Baseline imbalances not reported. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | Parallel 3‐arm cluster‐RCT conducted at 24 sites in Bangladesh (Sylhet district) between Jul 2003 and Dec 2005. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 24 clusters (113816 women; 46,444 live births analysed). Clusters: 24 clusters (with a population of about 20,000 each) in Sylhet district, a district with poor access to health care, about 15,000 livebirths per year, and the presence of non‐government organisations with the ability to scale‐up the intervention. The area also has the highest neonatal mortality in Bangladesh. Individuals: ever‐married women of reproductive age (15–49 years old). | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (addition of home visits) and community (IEC). Arm 1 (8 clusters, 36,059 women): (Home care) the CHWs identified pregnancies through routine surveillance during visits to each household once every 2 months; promoted birth and newborn care preparedness through 2 scheduled antenatal and 3 early postnatal home visits; and provided iron and folic acid supplements during birth and newborn‐care preparedness visits. Arm 2 (8 clusters, 40,159 women): (Community care) in the community‐care arm, female volunteers called community resource people were recruited in each village to identify pregnant women, encourage them to attend community meetings held by the community mobilisers, receive routine ANC, and seek care for signs of serious illness in mothers or newborns. Arm 3 (8 clusters, 37,598 women): (Usual care) families received the usual health services provided by the government, non‐government organisations, and private providers. | |

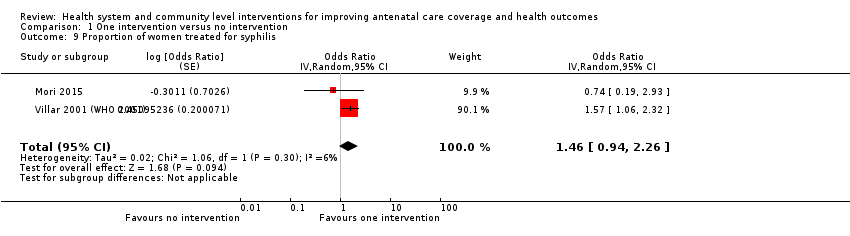

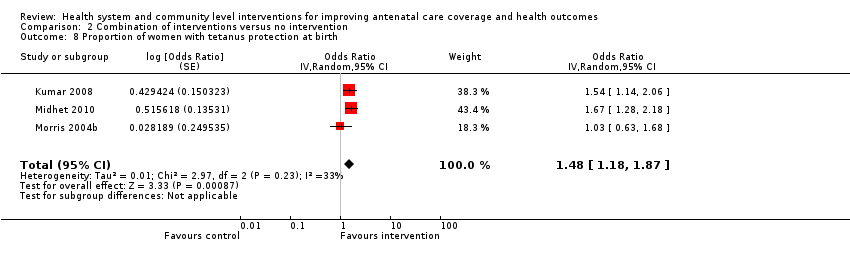

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: reduction in neonatal mortality. Review outcomes reported: Primary: not reported. Secondary: tetanus protection, at least 1 ANC visit, neonatal mortality. We have analysed these data by combining the 2 arms with individual interventions (home care or community care) compared to the control arm of standard care. Outcome data are included in our Comparison 1. | |

| Notes | Funders: United States Agency for International Development and saving newborn lives programme by Save the Children (US) with a grant from Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "computer generated pseudo random number sequence." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The computer‐generated randomisation was implemented by a study investigator who had no role in the implementation of the study." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | "nature of the intervention meant masking was unachievable." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Missing data described in study flow chart. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Most relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; ICC reported; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | Parallel‐arm cluster‐RCT conducted at 506 sites in Mexico between 1997 and 2003. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 506 clusters randomised (individuals not reported), 173 clusters analysed. Clusters: "The rural programme established eligibility in two stages: poor communities were first identified, and low‐income households were identified within those communities". Communities and households were randomly selected based on a probability sample proportionate to the number of women of reproductive age women (15–49 years). Individuals: the sample included women who experienced a singleton live birth between 1997 and 2003, were designated as poor and eligible for Oportunidades, and lived in the original treatment and control communities | |

| Interventions | Target: community (financial incentive intervention). Arm 1 (97 clusters, 810 women): Progresa or Opportunidades is a conditional cash transfer program established in 1997 in Mexico, with the dual aim of immediate poverty relief and long‐term impact on the generational transfer of poverty. Every 2 months intervention families received a cash transfer representing approximately a 25% increase in household income (Gertler 2000, p. 3). The cash transfer required specific health behaviours of all members of households. Pregnant women were required to have 5 prenatal visits beginning in the first trimester of pregnancy. Beneficiary births are those births that occurred after the household received their first cash transfer. Households in intervention areas began receiving benefits during the summer of 1998. Arm 2 (61 communities, 215 women): non‐beneficiary births are those that occurred among eligible women prior to receiving the first cash transfer. Households in control clusters began receiving benefits in November 1999. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: birthweight. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits). Secondary: at least 1 ANC visit, health facility deliveries, tetanus protection, low birthweight infants. | |

| Notes | The Mexican social welfare program Oportunidades (now Prospera) has multiple citations. We have incorporated data from a specific analysis conducted on a small sample of women in households involved in this large poverty relief program (Barber 2008). Funders: National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center TW006084 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | For the initial cluster‐randomisation, "random assignment was generated at the community level without weighting by use of the randomisation commands in Stata version 2.0" (Fernald 2008). For the survey, areas were randomly assigned "based on a probability sample proportionate to the number of women of reproductive age". p. 20 Barber 2009. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Due to the nature of the intervention participants could not be blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up described but sample sizes vary in the different reports. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Most relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | Parallel‐arm cluster‐RCT conducted at 166 sites in Rwanda between June 2006 and Oct 2006. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 166 clusters (2563 women). Clusters: districts without pre‐existing P4P schemes managed by non‐governmental organisations. Individuals: not described. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (financial intervention). Arm 1 (80 clusters, 1242 women): P4P scheme to supplement primary health centres’ input‐based budgets. In this P4P scheme, payments are made directly to facilities and are used at each facility’s discretion. Arm 2 (86 clusters, 1321 women): control facilities would continue to receive traditional input‐based financing for an additional 23 months until the rollout of the scheme was complete. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcomes: prenatal care visits and institutional deliveries. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits). Secondary: ANC coverage (at least 1 visit), health facility deliveries, tetanus protection, use of child preventative care. | |

| Notes | Funders: World Bank’s Bank‐Netherlands Partnership Program, the British Economic and Social Research Council, the Government of Rwanda, and the World Bank’s Spanish Impact Evaluation Fund; Global Development Network and the MacNamara Foundation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "The remaining districts were then grouped into eight blocks based on rainfall, population density, and livelihood data from the 2002 Census.15 Blocks covered between two and 4 districts, depending on district characteristics and size. The blocks were then divided into two sides, and one side of each block was randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. Randomisation was done by coin toss." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Women interviewed in households would not have been aware of their local facility's group assignment. Women attending facilities should also not have been aware of the funding scheme in operation at her local health clinic. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | "All surveys were done by trained enumerators hired by external firms specialised in data collection who were masked to whether they were interviewing in an intervention or control area." |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 2.1 % of intervention and 1.9% of control households refused to participate. 12% loss to follow‐up between baseline and end of trial surveys. 11.8% attrition in each treatment arm between first and second interviews. Incomplete household surveys were dropped from the sample after each round. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Most relevant outcomes are reported. |

| Analysis bias | Unclear risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters, ICC and ITT not reported. |

| Other bias | High risk | Allocation assignment not respected due to government restructuring. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | Due to uncertainties raised above. |

| Methods | Parallel‐arm cluster‐RCT conducted at 16 sites in Pakistan (Hala and Matiari sub districts) between Feb 2006 and Mar 2008. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 16 clusters (51409 individuals). Clusters: catchment areas of primary care facilities with adequate numbers of LHWs. Individuals: not described. Exclusion criteria: areas with low numbers of LHWs and areas with poor access were excluded. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (health worker education) and community (IEC intervention). Arm 1: the intervention package was delivered by trained LHWs through group sessions consisted of promotion of ANC and maternal health education, use of clean delivery kits, facility births, immediate newborn care, identification of danger signs, and promotion of care seeking. Arm 2: in the control clusters, the LHW programme continued to function as usual and no additional attempt was made to link LHWs with the Dais or communities. | |

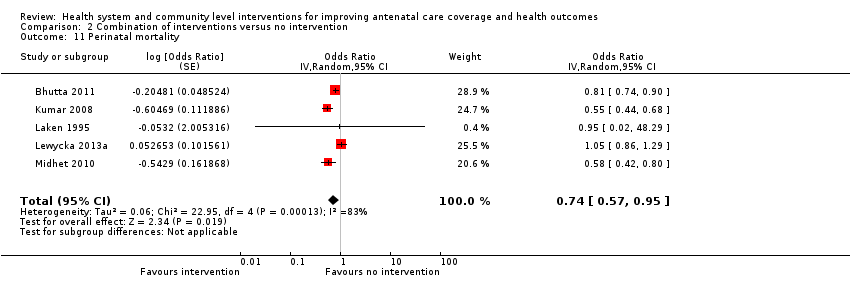

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: perinatal and all‐cause neonatal mortality. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits). Secondary: ANC coverage (at least 1 visit), professional ANC, health facility deliveries, perinatal mortality, stillbirth, neonatal mortality. Follow‐up: every 3 months for 2 years. | |

| Notes | Funders: grants from the WHO and the Saving Newborn Lives programme funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "From this list of balanced allocations, we selected one scheme using a computer generated random number." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Data collectors and their supervisors were masked to cluster allocation p. 406 Bhutta 2011. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Only 414 lost to follow‐up (less than 1%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Most relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; ICC reported; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | Parallel arm cluster‐RCT conducted in Mirzapur, Bangladesh, between Dec 2003 and Dec 2006. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 12 clusters (21,140 individuals randomised, 10,700 women with at least 1 pregnancy during 10 preceding months analysed). Clusters: rural unions surrounding an urban central union (excluded from the study) served by a 750 bed private referral‐level hospital. Individuals: all married women of reproductive age (i.e. 15–49 years) in the intervention arm were eligible for enrolment. Women in the survey were eligible if they had had a pregnancy outcome in the last 3 years. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (addition of home visits). Arm 1: 2 home visits (12‐16 and 32‐34 weeks); they were given a labour card for women to present upon arrival at hospital for delivery and 3 postnatal visits on days 2, 5 and 8. CHWs facilitated free‐of‐charge transfer of ill neonates to hospital.The purpose of the antenatal component of the intervention was to increase uptake of ANC (3 visits taking place at home or at a health centre or satellite clinic ‐ distinct from the 2 antenatal CHW home visits), tetanus toxoid vaccination, general pregnancy and newborn care education, and birth preparedness (including delivery at a health facility). Arm 2: standard ANC. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcomes: antenatal and immediate newborn care behaviours, knowledge of danger signs, care seeking for neonatal complications, and neonatal mortality. Review outcomes reported: Primary: not reported. Secondary: ANC coverage (at least 1 visit), health facility delivery, IPT for malaria, neonatal mortality. | |

| Notes | Funders: The Wellcome Trust: Burroughs Wellcome Fund Infectious Disease Initiative 2000 and the Office of Health, Infectious Diseases and Nutrition, Global Health Bureau, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Global Research Activity Cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (award HRN‐A‐00‐96‐90006‐00). Support for data analysis and manuscript preparation was provided by the Saving Newborn Lives program through a grant by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to Save the Children‐US. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov, No. NCT00198627. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation of clusters with a computer‐generated randomisation sequence. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Study flow chart with details of exclusions. Response rate for the endline survey reported as 87.8% (11731/16771). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Data for proportion of women who received 2 tetanus toxoid immunisations were not reported. The authors report falling rates during the trial and attribute this to a national shortage of vaccine. |

| Analysis bias | Unclear risk | Method of analysing clusters not clearly described apart from stating ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Baseline characteristics similar between arms. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | Due to uncertainties raised above. |

| Methods | Parallel‐arm cluster‐RCT conducted at 18 sites/unions in Bangladesh between Jan 2009 and June 2011. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 18 clusters (532,996 population). Clusters: purposeful selection of the 3 districts on the basis of having active Diabetic Association of Bangladesh offices and somewhat representing the social and geographical diversity of Bangladesh..basis of perceived limited access to perinatal health care and feasible accessibility from Diabetic Association of Bangladesh district headquarters. Individuals: women whose childbirths or deaths were recorded in the study areas. | |

| Interventions | Target: community (IEC intervention). Arm 1 (9 clusters, 12,135 women/births): women's participation groups; effect of monthly participatory learning and action cycle focus on maternal and newborn health. Arm 2 (9 clusters, 13,459 women/births): control not described (presumably no women's participation groups). | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: neonatal mortality rate. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits). Secondary: health facility deliveries, perinatal and neonatal mortality. 1 of the control areas (with 3 clusters) included "tea‐garden estates". Residents on these estates were described as having more social and economic disadvantage, and separate analyses were carried out including and excluding these areas. For the analyses in this review, we have used the outcome data that excludes these tea garden residents. | |

| Notes | Funders: Big Lottery Fund International Strategic Grant, Wellcome Trust Strategic Award. For the outcome of perinatal mortality we have used stillbirths plus early neonatal deaths. We calculated our own OR using an ICC because the adjusted perinatal deaths OR (without Tea Garden residents) is asymmetrical and would not go into RevMan. See Fottrell 2013 (Table 3, p. 823). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Paper stated that the sequence "had been decided before drawing the papers" (containing the allocation). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocated "by blindly pulling pieces of paper, each representing 1 union from a bottle". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | The intervention was not masked, it is not clear how lack of blinding might affect outcomes reported. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | The implementation and in‐country monitoring and evaluation teams were blind to the allocation arms" during interim analysis (June 2011). |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Study flow chart included displaying reasons for exclusions. Missing data described as 13% on home delivery practice and 0.8% on other secondary outcomes. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Relevant outcomes reported although separate analyses for some control group births meant that results were more difficult to interpret. |

| Analysis bias | Unclear risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters but ICC not reported and ITT analysis only performed for primary outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | 1 of the control areas (with 3 clusters) included "tea‐garden estates"; residents on these estates were described as having more social and economic disadvantage and separate analyses were carried out including and excluding these areas. For the analyses in this review, we have used the outcome data that excludes these tea garden residents. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | We were uncertain whether some of the above might have significantly biased the results. |

| Methods | Parallel‐arm individual‐randomised RCT conducted at 3 primary care trusts in Birmingham, UK between Jul 2010 and Oct 2011. Trial name: ELSIPS. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 1324 women. Inclusion criteria: nulliparous women < 28 weeks' gestation assessed by a midwife as having specific social risk. (Risk factors included housing problems, lack of social support, smoking, low maternal weight or obesity, teenage, late booking for ANC.) Exclusion criteria: women under 16 years of age, or teenage mothers recruited to another national trial of additional support during pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (re‐organisation of health services: home visits). Arm 1 (662 women): POW provided support, including home visits, in addition to standard ANC and PNC. The POW organised antenatal visits and advised on lifestyle changes. In addition to emotional and health‐related support, the POW helped with financial, legal or benefits problems and with housing. The POW also provided support with care of the newborn, including breastfeeding. Arm 2 (662 women): women in the control group received standard ANC and PNC. | |

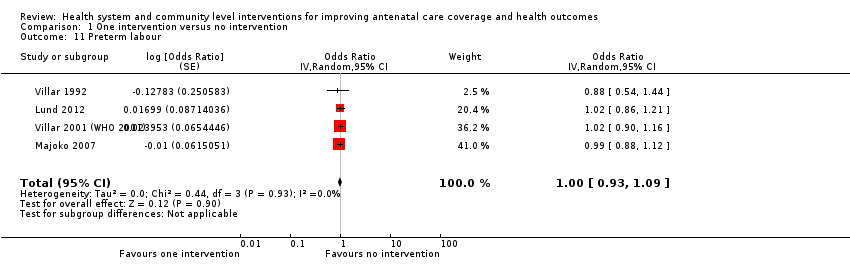

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale1 (EPDS) 8–12 weeks postpartum and antenatal visits attended. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 10 contacts). Secondary: preterm birth (< 34 weeks), low birthweight infants, perinatal mortality. Other: depression scores. We did not include data for preterm birth < 34 weeks because our review's definition of preterm birth < 37 weeks. Outcome data from unpublished paper obtained from author: SL Kenyon, [email protected]. | |

| Notes | Funders: this work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Birmingham and Black Country (CLAHRC‐BBC) programme. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation generated by the trial statistician using computer‐generated lists with random block sizes stratified by area. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Telephone randomisation using a registered trial unit ensured allocation concealment. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Inadequate ‐ blinding not possible. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Outcomes were recorded in maternity care notes by staff providing care. Those who collected and entered data were blind to group assignment. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | Not applicable. Not a cluster‐randomised trial. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Data on antenatal outcomes available for 100% and 99%. Data for the EPDS at 8‐12 weeks postpartum were available for 82% and 85% of the intervention and control arms. respectively. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes stated in protocol are reported in the unpublished paper, with the exception of "engagement with other services, as required (e.g. smoking cessation services)". |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Baseline characteristics similar between treatment groups. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns for primary outcomes. |

| Methods | Parallel‐arm cluster‐RCT conducted in Ghana between Nov 2008 and Dec 2009. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 98 clusters (18,609 individuals). Clusters: residential zones. Individuals: all pregnant women and newborn babies living in the Newhints zones, where pregnancies ended between November 2008 and December 2009. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (added home visits by community‐based surveillance volunteers) and community (IEC). Arm 1 (49 clusters, 9174 women): training of community‐based surveillance volunteers to identify pregnant women in their community and to undertake 2 home visits during pregnancy and 3 visits after birth on days 1, 3, and 7, to promote essential newborn‐care practices, and to assess and refer sick newborn babies. Arm 2 (49 clusters, 9435 women): control (no intervention). | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: neonatal mortality rate and coverage of key essential newborn‐care practices. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits). Secondary: health facility deliveries, neonatal mortality. Other: coverage of key essential newborn care practices. | |

| Notes | Funders: WHO, Save the Children’s Saving Newborn Lives Programme from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the UK Department for International Development. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "computer generated randomisation." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | An independent epidemiologist conducted the randomisation. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 3 groups of pregnancies were not included in the analysis of NMR: 908 (5%) women were lost to follow‐up during pregnancy; 1216 (7%) had pregnancies that ended early and did not result in a livebirth or stillbirth; and 156 (< 1%) women moved, resulting in a change of treatment groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Most relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; ICC reported; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances noted. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | Parallel‐arm individually‐randomised RCT conducted in the USA between Mar 94 and Jun 98. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 656 women. Inclusion criteria: African American, eligible for Medicaid, less than 26 weeks' gestation, at least 16 years old, score of 10 or higher on a risk assessment scale. Exclusion criteria: alcoholism and substance abuse, asthma, cancer, diabetes, epilepsy, high blood pressure, sickle cell disease and HIV/AIDS. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (additional and longer appointments) and community (IEC). Arm 1: educational intervention informing women about their risk conditions and what behaviours might improve their pregnancy outcome. Augmented care included educationally oriented peer groups, additional appointments, extended time with clinicians, and other supports. Arm 2: control (no intervention). | |

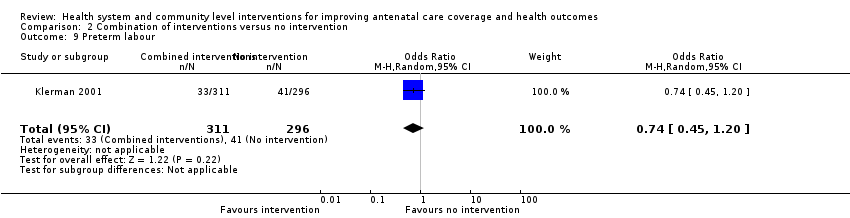

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcomes: pregnancy outcomes, women's knowledge of risks, satisfaction with care. Review outcomes reported: Primary: not reported. Secondary: preterm birth, low birthweight infants. Other: average no. of ANC visits. | |

| Notes | Funders: Federal Agency for Health Care Policy and Research to the University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation not described. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "sealed envelopes." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | "interviewers blinded" to treatment allocation. Additional outcome data taken from clinic records, data collection forms and a computerised database. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | Not applicable. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Missing data < 10%. 656 women enrolled, but data available for 619; 12 women with fetal deaths excluded from analysis (intervention group: 3 before 20 weeks and 4 after; controls: 3 before 20 weeks and 2 after). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Unclear risk | ITT not stated. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | Parallel 3‐arm cluster‐RCT conducted in India between Jan 2004 and May 2005. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 39 clusters (3891 individuals analysed). Clusters: administrative units. Individuals: all mothers who had delivered during the study period and were available for interview. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (home visits) and community (IEC). Arm 1 (13 clusters): a preventive package of interventions for essential newborn care (birth preparedness, clean delivery and cord care, thermal care [including skin‐to‐skin care], breastfeeding promotion, and danger sign recognition). The strategy included 2 prenatal (60 days and 30 days before expected date of delivery) and 2 postnatal (day 0 and day 3) home visits, community meetings and folk‐song meetings, maternal and newborn health stakeholder meetings, and meetings for community volunteers. Arm 2 (13 clusters): received same package of essential newborn care plus use of a liquid crystal hypothermia indicator (ThermoSpot; a sticker that indicates hypothermia in the newborn by changing colour). Arm 3 (13 clusters): received the standard care available from government and NGO providers in the area. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: newborn care practices and neonatal mortality rate. Review outcomes reported: Primary: not reported. Secondary: maternal mortality (up to 6 weeks postpartum), ANC coverage (at least 1 visit), health facility deliveries, tetanus protection, stillbirths, neonatal mortality. Other: essential newborn care measures, breastfeeding. | |

| Notes | Funders: The United States Agency for International Development, Delhi Mission, and the Saving Newborn Lives program of Save the Children US through a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Perinatal mortality included neonatal deaths up to 28 days after birth. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified cluster‐randomisation conducted at Johns Hopkins University using a computer program. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation performed remotely. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding not possible. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Preliminary analysis (2005) of neonatal mortality rate was said to be masked. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up described in study flow diagram with missing data < 20%. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; no ICC reported; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | 3‐arm, individually‐randomised RCT conducted in Detroit, USA; recruitment dates not reported. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 205 individuals. Inclusion criteria: low‐income women who entered prenatal care at a local clinic before 32 weeks' gestation and who delivered at a tertiary‐level hospital. Exclusion criteria: not reported. | |

| Interventions | Target: community (financial incentive intervention). Arm 1 (51 women): women received gift certificates for each prenatal appointment. Arm 2 (53 women): women received gift certificates and a chance to win in a $100 raffle. Arm 2 (101 women): no financial incentive. Women in all 3 groups were offered $10 for the postnatal interview. | |

| Outcomes | Triap Primary Outcome: kept appointments for antenatal care and postpartum care Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits). Secondary: maternal mortality, health facility deliveries, perinatal mortality. | |

| Notes | Funders: Michigan Health Care Education and Research Foundation. Authors provided unpublished data for coverage, mortality and health facility deliveries by email on 16/1/15. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "random numbers were used" for group assignment. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Clinic staff members were blind to assignment, but women would have been aware of their own assignment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | Not applicable. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Missing data < 20% for birth outcomes (low risk) but high loss to follow‐up at the postnatal interview (45%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Relevant outcomes reported, but insufficient data provided. |

| Analysis bias | Unclear risk | Methods not reported in sufficient detail. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to make a judgement. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to make a judgement. |

| Methods | Parallel‐arm cluster RCT conducted at 26 sites in South Africa between May 2009 and Sept 2010. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 26 clusters (24 clusters and 1238 individuals analysed). Clusters: neighbourhoods were matched. Eligible neighbourhoods had 450‐600 households, with formal and informal housing, that were within 5 km of health clinics; had 5 to 7 alcohol bars; were noncontiguous or separated by natural barriers; had similar numbers of child care centres, informal shops, and schools; and had households with similar length of residence. Individuals: pregnant women were recruited at an average 26 weeks of pregnancy (range, 3–40 weeks). 94 women in 10 of the 12 standard care neighbourhoods were enrolled post‐birth. Approximately 25% of women in each treatment arm were living with HIV. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (added home visits) and community (IEC). Arm 1 (12 clusters, 644 women): Philani Intervention Program, home visits by CHWs in addition to standard care. Arm 2 (12 clusters, 594 women): standard care, comprehensive healthcare at clinics. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcomes: composite of maternal and child health and well being measures. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits). Secondary: HIV screening, complete antiretroviral course, low birthweight infants. Mortality data for women and infants are reported in the primary trial report. However, these data represent all deaths within the particular time frame of data collection (e.g. all deaths to 6 months post birth, p. 1464 of the 2013 trial report). We consulted with trial authors, but we cannot recalculate the mortality data to fit standard definitions for pregnancy‐related deaths or perinatal deaths. We were particularly concerned that maternal deaths may have been unrelated to pregnancy. We were therefore unable to use mortality data in meta‐analysis. | |

| Notes | Funders: NIAAA Grant # 1R01AA017104 and supported by NIH grants MH58107, 5P30AI028697, and UL1TR000124. M.T. is supported by the National Research Foundation (South Africa). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation not described. Method described as simple randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Neighbourhoods were randomised in matched pairs using simple randomisation. Randomisation conducted by an independent research team (UCLA). |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | "interviewers were blinded but may have known from participants about CHWs." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | A driver transported all participants to a central assessment site, allowing interviewers to be blind to group allocation. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | High risk | "Initially, however, we identified 22% fewer pregnant women in standard care. By redeploying recruiters, we identified an additional 94 women in 10 of the 12 standard care neighbourhoods who were pregnant during the recruitment period (median of 7 late‐entry participants per neighbourhood; range, 3–24). These women were enrolled post‐birth when their infants were a mean age of 9 months old (range, 1–18 months). The final sample (n = 1238) consisted of a median of 51 pregnant women per neighbourhood (range, 23–72)." Analyses were conducted with and without late‐entry participants and results were similar. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | 1 matched cluster pair was excluded after 6 months due to poor recruitment. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes were reported. |

| Analysis bias | Unclear risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; no ICC reported; ITT analysis not performed. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | We were uncertain what impact potential biases mentioned above had on results. |

| Methods | 2 by 2 factorial cluster‐RCT conducted in Malawi between 2005 and 2009. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 42 clusters (18960 pregnancies, 18,744 livebirths analysed). Clusters: the unit of randomisation was a cluster of villages and not an individual village. Cluster design was based on census enumeration areas with population of approximately 3000, surrounded by a buffer zone to reduce contamination. The target population was rural communities; the urban administrative centre of the district was excluded. Individuals: all women aged 10‐49 who were willing to participate were enrolled. Women who had a terminal family planning procedure were excluded from the final sample, but not from participating in the intervention. | |

| Interventions | Target: community (IEC). Arm 1 (12 clusters, 4557 pregnancies): facilitator initiated women's groups to discuss issues of pregnancy, childbirth and newborn and infant health, as well as peer counselling (infant feeding and care counselling via 5 home visits during and after pregnancy (3rd trimester, week after birth, at 1, 3 and 5 months). Arm 2 (12 clusters, 4722 pregnancies): facilitated women's groups. Arm 3 (12 clusters, 4660 pregnancies): peer counselling via home visits. Arm 4 (12 clusters, 5021 pregnancies): no intervention. All clusters benefited from training of staff in health facilities in essential newborn care. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcomes: maternal, perinatal, neonatal and infant mortality rates, and exclusive breastfeeding. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits), maternal mortality. Secondary: ANC coverage (at least 1 visit), health facility deliveries, IPT for malaria, tetanus protection, HIV screening, perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality. | |

| Notes | Funders: Saving Newborn Lives, UK Department for International Development, Wellcome Trust, Institute of Child Health, and UNICEF Malawi. The primary trial report presents several different analyses, including 1 where Interventions were combined, in order to evaluate the effect of women's groups (arm 1 + 2 combined versus arm 3 + 4 combined) and the effect of peer counselling (arm 1 + 3 combined versus arm 2 + 4 combined) separately. For the analysis in our review's Comparison 1: Lewycka 2013a refers to the women's group intervention only. Lewycka 2013b refers to the peer counselling intervention only. These 2 single‐intervention arms are compared to the arm with no intervention. For the analysis in our review's Comparison 2: Lewycka 2013a refers to the trial arm that received both women's groups and peer counselling. This arm is compared to the arm with no intervention. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation done with computer program Stata. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Group assignment was masked for data analysis. Data collection was conducted independently of program implementation and was not fed back to inform the intervention. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Women with miscarriages were excluded from analysis. Loss to follow‐up about 20%. Miscarriage rates varied across study arms and were more frequent in the combined intervention cluster. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; no ICC reported; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The authors discuss an interaction between the 2 interventions and baseline imbalances after randomisation across several outcomes. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | We were concerned that the exclusion of women with miscarriages might bias maternal death rates. |

| Methods | 2 by 2 factorial cluster RCT conducted in Malawi between 2005 and 2009. Lewycka 2013b describes the same trial as Lewycka 2013a above, and all of the descriptions and risk of bias are identical to that above. We have had to duplicate the 'Risk of bias' judgements below due to RevMan requirements. | |

| Participants | For the analysis in our review's Comparison 1: Lewycka 2013a refers to the women's group intervention only. Lewycka 2013b refers to the peer counselling intervention only. These 2 single‐intervention arms are compared to the arm with no intervention. | |

| Interventions | See Lewycka 2013a. | |

| Outcomes | See Lewycka 2013a. | |

| Notes | See Lewycka 2013a. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation done with computer program Stata. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Group assignment was masked for data analysis. Data collection was conducted independently of program implementation and was not fed back to inform the intervention. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Women with miscarriages were excluded from analysis. Loss to follow‐up about 20%. Miscarriage rates varied across study arms and were more frequent in the combined intervention cluster. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; no ICC reported; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The authors discuss an interaction between the 2 interventions and baseline imbalances after randomisation across several outcomes. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | We were concerned that the exclusion of women with miscarriages might bias maternal death rates. |

| Methods | A parallel arm cluster‐RCT conducted on the island of Unguja, Zanzibar, Tanzania between Mar 2009 and Mar 2010. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 24 clusters (2367 individuals randomised, 2550 analysed). Clusters: government‐run primary healthcare facilities, 4 per district, were selected, based on 2 inclusion criteria: highest number of ANC clients in 2008 and the availability of at least 1 midwife in the facility. All included facilities had mobile phone network coverage. Individuals: women who attended ANC at 1 of the 24 selected healthcare facilities were included on their first ANC visit and followed until 42 days after delivery. Women were eligible for study participation irrespective of their mobile phone and literacy status. Exclusion criteria: PIH, anaemia, multiple pregnancy and malpresentation. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (policy/practice change). Arm 1 (12 clusters, 1351 women): women received an automated text messaging service for health information and appointment reminders, mobile phone vouchers to enable women to contact health services. The content of messages depended upon gestational age. Women received 2 messages/month < 36 weeks and then 2 per week. Only women with registered phone numbers received text messages; women without received only vouchers with mobile credit. Arm 2 (12 clusters 1286 women): women attending control health facilities received standard ANC, with the goal of at least 4 ANC visits. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: skilled delivery attendance. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits), maternal mortality. Secondary: tetanus protection, perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality. Other: skilled birth attendant (midwife/doctor/nurse) at delivery. Follow‐up: women were offered at least 4 antenatal visits and a postnatal home visit within 48 hours after delivery. Women were interviewed for demographics at trial entry at 6 weeks after delivery. The trial definition of perinatal mortality is non‐standard, stated as stillbirth and death of the infant up to 42 days. | |

| Notes | Funders: Danish International Development Cooperation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation described as 'simple randomisation' but sequence generation not described. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Clusters and study participants were not masked due to the nature of the intervention requiring overt participation. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Exclusions/withdrawals < 20% were due to exclusion criteria (development of complications) or loss to follow‐up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters, ITT analysis was performed. No ICC reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No baseline imbalances noted. The trial definition of perinatal mortality is non‐standard, stated as stillbirth and death of the infant up to 42 days. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | Parallel arm cluster‐RCT conducted in a rural setting in Zimbabwe between Jan 1995 and Oct 1997. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 23 clusters (13517 individuals). Clusters: health centres in a rural setting. Gutu district was chosen as the study area because the utilisation of maternity services and reproductive health status of the community had been previously studied.The district had 25 health facilities, comprising a district hospital and 24 rural health centres (RHCs) serving a population of 195 000. Individuals: all mothers booking for ANC since 01/12/94. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (re‐organisation of ANC). Arm 1: an experimental package of ANC with reduced procedures, clear goals and symphysio‐fundal height measurements. Visits scheduled according to a 5 visit program with reduced routine procedures at these visits. First visit: risk assessment, health education and delivery plan, Hb, rapid plasma reagin, tetanus vaccination and do urinalysis. Visit 2 at 24–28 weeks: exclude multiple pregnancy, check for hypertensive disorders, and do urinalysis. Visit 3 at 32–34 weeks: Exclude anaemia, check fetal growth and review delivery plans, check Hb and do urinalysis. Visit 4 at 36–38 weeks: check fetal growth, exclude abnormal presentation, discuss labour and do urinalysis. Visit 5 at 40–41 weeks: check fetal well being, referral for post‐term induction at 42 weeks and do urinalysis. Arm 2: the control arm followed the standard schedule with a visit every 4 weeks from booking until 28 weeks, every 2 weeks between 28 and 36 weeks and weekly after 36 weeks until delivery. Risk assessment was performed at the booking and subsequent visits, and referral for hospital delivery was made using a list of risk markers recommended by the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. Blood pressure, body weight and urinalysis were measured at each visit, while Hb and syphilis test (RPR) were performed at the first visit. Women who tested positive for syphilis had treatment initiated at the booking visit. Oral iron supplementation was provided to all women in both models. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcomes: number of antenatal visits, referrals for antenatal, intrapartum or postpartum problems, place of delivery and low birthweight infant (< 2500 g). Review outcomes reported: Primary: maternal mortality. Secondary: health facility deliveries, preterm birth, perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality. | |

| Notes | Funders: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida/SAREC) through the Sida–University of Zimbabwe Reproductive Health Research Programme. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation not described. Randomisation described as stratified according to the availability of telecommunication for referrals. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 13,517 women randomised. Full records were available for 78% of women with curtailed follow‐up for an additional 20%. Communication with the authors has clarified the numbers used for perinatal deaths, adding back in many women whose records were not retrieved. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. The authors were contacted to clarify the numbers used to calculate perinatal death. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; no ICC reported; ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns after contacting authors with data queries. |

| Methods | Parallel arm cluster‐RCT conducted in a rural setting in Nepal between Sept 1999 and Nov 2003. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 24 clusters (28931 individuals). Clusters: Rural Village Development Committees were matched for geography, population and ethnicity; 12 pairs were randomised. Individuals: married women aged 15‐49 residing within the study area who could potentially conceive within the period of the study. Exclusion criteria: unmarried women, permanently separated or widowed women; women under the age of 15 or older than 49. | |

| Interventions | Target: community (IEC intervention). Arm 1 (12 clusters, 14,884 women): participatory women's groups facilitated by a female facilitator who convened 9 women's group meetings every month. The facilitator supported groups through an action learning cycle in which they identified local perinatal problems and formulated strategies to address them. Arm 2 (12 clusters, 14,047 women): health service strengthening activities were undertaken in both intervention and control areas. These improvements included provision of equipment. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: neonatal mortality rate. Review outcomes reported: Primary: not reported. Secondary: ANC coverage (at least 1 visit), health facility deliveries, perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality. The adjusted OR for maternal mortality was taken directly from the systematic review Prost 2013. | |

| Notes | Funders: DFID, with important support from the Division of Child and Adolescent Health, WHO, the United Nations Children's Fund, and the United Nations Fund for Population Activities. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequence to randomised pairs was from a random numbers list; to randomise within pairs a coin toss was used. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation sequence was generated centrally (Kathmandu) before enrolment of participants in relevant clusters. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessor was blinded to group allocation. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All clusters analysed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Unclear risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; ITT analysis performed; ICC not reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances noted. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | No serious risk of bias concerns. |

| Methods | Parallel arm, individually‐randomised RCT conducted at 5 sites in the USA between Jan 94 and Dec 95. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 104 women. Inclusion criteria: all pregnant women planning to attend prenatal care at 1 of 5 participating family planning and women's health clinics. All randomised women were eligible for the state of California's Medicaid program (assistance with healthcare costs). Exclusion criteria: women planning prenatal care at another location or women considering abortion. | |

| Interventions | Target: community (financial incentive). Arm 1: 34 women were randomised to receive at taxi voucher and 35 received a coupon for a baby blanket. Arm 2: the control group received no incentive to attend the first antenatal appointment. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: compliance with the first prenatal appointment. Review outcomes reported: Primary: not reported. Secondary: not reported. | |

| Notes | Funders: funded in part by a grant from the American Academy of Family Physicians' Foundation. No usable data. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequence from a table of random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes were prepared remotely from clinics. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Women were not told that the study had to do with appointment compliance. It is not clear if staff were aware of group assignment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Outcomes assessors for the primary outcome were blind to group assignment. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | Not applicable. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 22/69 (32%) in the intervention group lost to follow‐up and excluded; 8/35 in controls. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No review outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No baseline imbalances noted. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | High loss to follow‐up with no relevant review outcomes. |

| Methods | Parallel arm cluster‐RCT conducted in Balochistan, Pakistan. A baseline survey took place in Aug‐Sept 1998. Intervention package in place by March 2000; follow‐up survey was conducted between March and April 2002. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 32 clusters (2561 individuals analysed). Clusters: Balochistan is an underdeveloped and poor region of Packistan with the highest maternal mortality rate. Each eligible village cluster had between 5‐15 villages. The project area was divided into 3 zones based on distance from the district hospital. Randomisation took place within each zone. Individuals: women who had had a pregnancy in the last 12 months. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (health worker education and re‐organisation of services ‐ transport) community (IEC intervention). Arm 1: women were provided information on safe motherhood through pictorial booklets and audiocassettes; TBAs were trained in clean delivery and recognition of obstetric and newborn complications; and emergency transportation systems were set up. The intervention was delivered to women only in 1 group and to both women and husbands in another. Arm 2: the project provided training for health professionals at the district hospital, who provided care for women from both intervention and control clusters. Government healthcare providers also trained staff in primary health facilities throughout the study area. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcomes: perinatal or neonatal death; use of iron‐folic acid. Review outcomes reported: Primary: not reported. Secondary: ANC coverage (at least 1 visit), health facility deliveries, tetanus protection, perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality. The perinatal death outcome seems to have been calculated with live births rather than all births. For our analyses, we have used data from the 2002 follow‐up survey only. | |

| Notes | Funders: NICHD, USAID, UNICEF, World Health Organization, British Council, Government of Japan and The Asia Foundation, and implemented by The Asia Foundation’s Islamabad office. Residual impact survey conducted 2 years after project ended, in 2004; on a sample of 900 women randomly selected from immunisation records at the district health office. We have used data from the original cluster‐randomised trial only. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation by "blindly drawing village cluster names written on folded chits". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Unclear risk | At the 2002 follow‐up survey, intervention clusters were expanded, resulting in 47% increase in size of the control arm. At the 2004 follow‐up survey, refusals or locked households in a selected cluster were replaced by the nearest available household. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | The follow‐up survey interviews were completed for 95.2% of visited households. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Relevant outcomes were reported. |

| Analysis bias | Unclear risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; ICC reported; ITT not stated. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Information bias. Most of the results are from the 2002 follow‐up survey, but authors state that some data are from the 2004 survey. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | We were uncertain whether the risk of bias concerns above might have impacted the results. |

| Methods | A parallel arm cluster‐RCT conducted in India between Oct 2006 and Sept 2009. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 48 clusters (18,197 individuals). Clusters: eligible clusters were communities in urban slums in Mumbai for which a perinatal vital registration was set up as part of the City Initiative for Newborn Health in 2005. The wards were selected purposively for the 2005 Initiative based on accessibility and relative infant mortality rates. Communities with transient populations and areas where resettlement was being negotiated were both excluded. Individuals: women of all ages residing in intervention clusters, whether pregnant or not pregnant, were invited to attend women's groups. | |

| Interventions | Target: community (IEC intervention). Arm 1: women were invited to weekly meetings that emphasized knowledge of local health services, perinatal health care, and negotiating optimal care with family and health providers. Arm 2: no weekly meetings. Surveillance data were collected in both intervention and control areas. 12 interviewers collected these data at 6 weeks postpartum. Unwell mothers or infants in either arm were referred and treatment expedited. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: perinatal care, maternal morbidity, and extended perinatal mortality. Review outcomes reported: Primary: maternal mortality. Secondary: professional ANC, health facility delivery, perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality. | |

| Notes | Funders: ICICI Foundation for Inclusive Growth – Centre for Child Health and Nutrition, and the Wellcome Trust. DO was funded by a Wellcome Trust Fellowship (081052/Z/06/Z). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation by "drawing of lots". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation not concealed. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Interviewers may have been aware of the assignment of their particular area, but the authors argue that they "were focused on their task (surveillance) and did not dwell on the comparative nature of the trial." Data analysts were blinded. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Unclear risk | 9 clusters were expanded for insufficient births, and 2 clusters reduced for excess births. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Attrition was less than 20% in each arm, and authors have provided a study flow diagram with documented reasons for loss to follow‐up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes were reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters; ITT analysis performed; ICC not reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Other initiatives during the trial period include outreach services by health volunteers, birth registration and pulse polio campaigns and infectious disease surveillance. Conditions in slums improved over the trial period. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | We were uncertain whether the risk of bias concerns above might have impacted the results. |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT in Bulgan, Mongolia. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 501 women randomised. Clusters: the unit of randomisation was the Soum and bag, small geographic areas in Mongolia. Each Soum has a healthcare facility where women must register their newborn. 18 geographic areas were randomised, after selection for administrative convenience and to avoid contamination. Individuals: pregnant women living in Bulgan, Mongolia. | |

| Interventions | Target: community. Arm 1: distribution of maternal and child health handbooks during pregnancy. The MCH handbook logged maternal health and personal information, pregnancy, delivery and postpartum health and weight, dental health, parenting classes, child developmental milestones from 0‐6 years, immunisation records and height and weight charts for children. Arm 2: women received standard care. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: number of antenatal visits; proportion of women attending 6 or more antenatal visits. (The national standard for ANC in Mongolia is 6 visits.) Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage of at least 4 visits, maternal mortality Secondary: maternal outcomes: morbidity during pregnancy, mode of delivery, breastfeeding initiation, maternal depression and health (EPDS and GHQ). Infant outcomes: birthweight, Apgar score, NICU admission, neonatal mortality at discharge. Maternal healthy behaviours. Follow‐up: data collection at 1 month postpartum. | |

| Notes | Funders: this study was funded by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan. Significant group differences noted for distances travelled to nearest health centre (greater in the intervention group) and for wealth index (the control group was poorer). The authors report that travel time did not function as an effect modifier; however, women from a higher socioeconomic background attended more ANC visits. Trial authors provided unpublished outcome data upon request. The trial statistician (HN) calculated ORs and 95% confidence intervals using the generalised estimating equations (GEE) method to adjust for cluster design and baseline differences, including wealth. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequence according to the shuffling of sealed envelopes. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation was concealed in sealed envelopes at time of randomisation. All areas were randomised at the same time. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Masking was not possible for this intervention. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Masking was not possible for this intervention. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | No problems with recruitment are reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 3 randomised areas were excluded; 1 was the subject of a pilot study, and 2 areas were included in another health study. 9 clusters each received the intervention or the control. Missing outcome data for individual women is reported and minimal. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Prespecified outcomes have been reported. Addtional analyses were obtained from the authors upon request. The trial data file has been published online with the trial report. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analyses were undertaken with methods appropriate for cluster trials; the authors used GEE methods to adjust for the effects of cluster design and baseline variables. A sample size calculation was undertaken and met. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The authors reported baseline imbalances between clusters for travel time to health centre and wealth. The authors reported that recall bias may exist due to data collection at 1 month after birth. |

| Overall risk assessment | Low risk | Overall the trial was well planned and conducted. |

| Methods | Parallel arm cluster‐RCT conducted in Honduras between Aug 2000 and Oct 2002. | |

| Participants | Sample size: 70 clusters (˜5600 households). Clusters: municipalities, which were selected because they had the highest prevalence of malnutrition in the country. Individuals: women were eligible who had been pregnant during the previous 12 months but were not pregnant on the day of the interview. | |

| Interventions | Target: health system (financial resources to health team and training) and community (financial incentive and IEC). Arm 1: 1 (20 clusters): a household‐level package consisted of monetary vouchers paid to women in households whose residence in the beneficiary municipalities had been recorded in a special census done in mid‐2000. 3 (20 clusters): financial resources to local health teams combined with a community‐based nutrition intervention involving the training of lay nutrition promoters. 2 (10 clusters): both packages. Arm 2 (20 clusters): neither package. | |

| Outcomes | Trial primary outcome: use of health services. Review outcomes reported: Primary: ANC coverage (at least 4 visits). Secondary: tetanus protection. | |

| Notes | Funders: Government of Honduras. We have calculated a final score by adding the change scores to the baseline scores presented in the trial report, Table 2 Program Effects, p. 2034. For our review's Comparison 1: Morris 2004a is the 2 single intervention trial arms added together and compared with the control group. For our review's Comparison 2: Morris 2004b is the 'both packages' trial arm compared with the control group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Within each stratum, random allocation was achieved by a child drawing coloured balls from a box, without replacement. Thus, the randomisation was both stratified and blocked." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The aperture of the box was sufficiently small that once the child had inserted his or her arm, it was impossible for him or her to see the coloured balls. From the day of the randomisation onwards, there was no attempt to conceal the allocation." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Surveys were conducted by an independent data collection company. Not clear if individual interviewers would have been aware of cluster assignment. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Study flow chart included. Loss to follow‐up less than 5% in all arms. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters (no ICC reported); ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | High risk | The intervention involving direct transfer of resources to health teams and part of the service‐level package was not successfully implemented in the relevant clusters. Non baseline imbalances noted. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | We were uncertain whether the risk of bias concerns relating to poor implementation impacted the results. |

| Methods | This trial is the same as that described in Morris 2004a above. Due to RevMan requirements, we have replicated the 'Risk of bias' assessments below. However, Morris 2004b describes a specific 'both packages' arm of Morris 2004a and not a different study. | |

| Participants | For our review's Comparison 2, Morris 2004b is the 'both packages' trial arm compared with the control group. | |

| Interventions | See Morris 2004a. | |

| Outcomes | See Morris 2004a. | |

| Notes | See Morris 2004a. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Within each stratum, random allocation was achieved by a child drawing coloured balls from a box, without replacement. Thus, the randomisation was both stratified and blocked." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The aperture of the box was sufficiently small that once the child had inserted his or her arm, it was impossible for him or her to see the coloured balls. From the day of the randomisation onwards, there was no attempt to conceal the allocation." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Surveys were conducted by an independent data collection company. Not clear if individual interviewers would have been aware of cluster assignment. |

| Recruitment bias (for cluster RCTs) | Low risk | None noted. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Study flow chart included. Loss to follow‐up less than 5% in all arms. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Relevant outcomes reported. |

| Analysis bias | Low risk | Analysis appropriate for clusters (no ICC reported); ITT analysis performed. |

| Other bias | High risk | The intervention involving direct transfer of resources to health teams and part of the service‐level package was not successfully implemented in the relevant clusters. Non baseline imbalances noted. |

| Overall risk assessment | Unclear risk | We were uncertain whether the risk of bias concerns relating to poor implementation impacted the results. |

| Methods | A parallel, 3‐arm RCT conducted at 1 site in Nepal between Aug 2003 and Jan 2004. | |