نقش درمانهای روانشناختی برای درمان اختلالات اضطرابی در بیماری مزمن انسدادی ریه

Referencias

منابع مطالعات واردشده در این مرور

منابع مطالعات خارجشده از این مرور

منابع مطالعات در انتظار ارزیابی

منابع مطالعات در حال انجام

منابع اضافی

منابع دیگر نسخههای منتشرشده این مرور

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Country: Brazil Design: a blinded prospective RCT Multicentre?: no Funders of the trial: supported by the Universidade de Caxias do Sul (BPC level II grant) Duration of trial: October 1999‐May 2001 Duration of participation: 12‐week programme | |

| Participants | Population description: people with COPD treated at a pulmonary rehabilitation clinic in Brazil; participant's COPD was stratified according to the Brazilian Society of Pulmonology and Tisiology guidelines into 3 severity levels: mild, moderate and severe Setting: all participants were referred from the University's Department of Respiratory Diseases to the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Clinic Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of COPD (corroborated by clinical history, physical examination, spirometry, chest plain films, thoracic computer tomography or both and pulse oximetry Exclusion criteria: physical incapacity to perform the proposed protocol; refusal to participate in the pulmonary rehabilitation programme; lack of adherence to the pulmonary rehabilitation programme due to illness of more than 2 weeks' duration Method of participant recruitment: pulmonary rehabilitation clinic patients Total number randomised: 30 participants Withdrawals and exclusions: no withdrawals mentioned Age: mean age 60.33 Sex: 22 men and 8 women Race/ethnicity: not stated | |

| Interventions | Intervention Number randomised to group: 14 Details of the interventions:

Intervention intensity: 12‐week treatment programme with 12 psychotherapy sessions in addition to co‐interventions of 24 physiotherapy sessions, 24 physical exercise sessions and 3 educational sessions Mode of delivery: unclear if intervention was delivered in group settings or to individuals Co‐interventions:

Comparison Comparison name: reported as 'Group 2' in the paper Number randomised to group: 16 Details of the interventions:

Intervention intensity: 12‐week treatment programme with 24 physiotherapy sessions, 24 physical exercise sessions and 3 educational sessions Mode of delivery: unclear if intervention was delivered in group settings or to individuals | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes collected: BAI, BDI and 6MWD Time points measured: baseline and post‐intervention Person collecting time point: not specified Outcome measures validated?: yes for all three Missing data addressed?: not reported | |

| Notes | Note: no mention of a sample size calculation is made but authors do report the "relatively small sample size" as a limitation of the study. Funding: Supported by the Universidade de Caxias do Sul (BPC level II grant); No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the authors or upon any organization with which the authors are associated | |

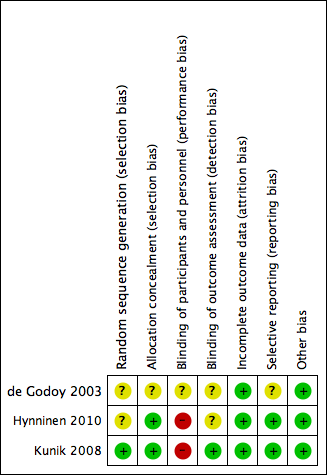

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not specified "patients were randomised into 2 groups" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Details of allocation concealment not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Group 1 was blinded in relation to the activities of Group 2 and vice versa |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No mention of blinding for outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Reasons for choosing not to participate prior to randomisation (n = 6 participants) and attrition post recruitment (n = 3 intervention participants) were reported for all participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insuffient information due to lack of prespecified study protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases identified |

| Methods | Country: Norway Design: prospective RCT Multicentre?: no Funders of the trial: no funding sources mentioned Duration of trial: participants were enrolled over a period of 1.5 years; no other information provided Duration of participation: 8 months from baseline | |

| Participants | Population description: people with COPD who answered positively to at least 2 of the 5 anxiety and depression questions from the PRIME‐MD questionnaire Setting: participants in both groups attended the pulmonary clinic at baseline and 2 and 8 months later for spirometry, self‐report measures and provision of Actigraph device for sleep registration Inclusion criteria: COPD diagnosis confirmed with post –bronchodilator spirometry FEV1 < 80% predicted and ratio < 0.7, aged 40 years or over, had BAI scores > 15 and/or BDI‐II > 13, not participating in other psychological interventions e.g. pulmonary rehabilitation, no cognitive impairment (MMSE score > 23) and no severe psychiatric disorders as per DSMIV Exclusion criteria: as per inclusion criteria Method of participant recruitment: consecutive eligible patients who were interested in participating in the study were recruited from an outpatient clinic at the Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway or were recruited via a newspaper advertisement Total number randomised: 51 participants Withdrawals and exclusions: intervention arm: 2 discontinued intervention; control arm: 2 could not be contacted and 1 died Age: intervention group: mean 59.3 years; control group: mean 62.6 years Sex: intervention group: 11 women, 14 men; control group: 15 women, 11 men Race/ethnicity: not reported | |

| Interventions | Intervention Number randomised to group: 25 (23 received allocated intervention) Details of the interventions:

CBT was undertaken in the Department of Clinical psychology. The group session was facilitated by two masters‐level psychology students; The sessions were videotaped and a specialist in clinical psychology monitored the students' competence Intervention intensity: 7 weekly 2‐h sessions Mode of delivery: group sessions (4‐6 participants, 5 on average) Co‐interventions

Comparison Comparison name: Enhanced Standard care for COPD Number randomised to group: 26 (23 received allocated intervention) Details of the interventions:

Intervention intensity: phone calls every 2 weeks for intervention period; Calls lasted 5‐10 min Mode of delivery: telephone Co‐interventions

| |

| Outcomes | Outcomes collected: BAI, BDI, SGRQ, PSQI, Actigraphy (objective measure of sleep efficiency) and CSQ Time points measured: baseline, 2 and 8 months (or baseline, post treatment and six months post treatment) Person collecting time point: not reported Outcome measures validated?: yes for all Missing data addressed?: yes, ITT analysis used and authors report that missing data at one measurement point did not prevent including the individual in the analysis | |

| Notes | Note: the target sample size identified as being necessary in the power analysis (33 in each arm) was not reached by the end of the study period (25 in the intervention arm and 26 in the control arm) Funding: no mention of funding or financial support for this work | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation reported however methods not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment was implemented using numbered containers that were identical in appearance for the two groups |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Neither participants nor therapists were blinded to the intervention |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No mention of blinding for outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Reasons for attrition reported in participant flow chart. Missing outcome data at one measurement point did not preclude analysis as mixed models with random effect was used for analysis; Intention‐to‐treat analysis occurred |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Prespecified protocol available and no selective reporting identified |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases identified |

| Methods | Country: USA Design: prospective RCT Multicentre?: no Funders of the trial: grant from Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development; Houston Centre for Quality Care and Utilization Studies and South Central Medical Illness Research, Education and Clinic Center, Department of Veterans Affairs Duration of trial: 11 July 2002‐30 April 2005 Duration of participation: 12 months' follow‐up from baseline | |

| Participants | Population description: people with a chronic breathing disorder (COPD) who had moderate anxiety symptoms and/or depression and were receiving care at the Michael E DeBakey VA Medical Centre (MEDVAMC) within the year before the study Setting: participants were from the Michael E DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas, USA and community members meeting the criteria outside of the medical centre Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of COPD confirmed with spirometry (ratio < 70 and FEV1 < 70; according to ATS 1991); moderate anxiety (BAI ≥ 16) and/or depression (BDI > 14); and treatment by primary care or provider or pulmonologist Exclusion criteria: cognitive disorder or evidence of score of 23 or less on MMSE, a psychotic disorder and people with psychotic and non‐nicotine substance use disorders Method of participant recruitment: people on administrative database from the Michael DeBakey Medical Center (MEDVAMC) were targeted for recruitment and screened, in addition to other methods including flyers and advertisements Total number randomised: 238 Withdrawals and exclusions: 69 participants dropped out following randomisation(because of the following reasons: medical 2, no time 6,transportation 6,no interest 49, no information 46). Age: Mean 66.3 + 10.2 years Sex: 226 men and 9 women in total Race/ethnicity: white n = 192, Hispanic n = 7 and black n = 38 | |

| Interventions | Intervention Number randomised to group: 118 (89 attended at least one CBT session) Details of the interventions:

Intervention intensity: eight 1‐h sessions Mode of delivery: group CBT (up to 10 participants each session) Co‐interventions

Comparison Comparison name: COPD Education Number randomised to group: 120 (92 received the education intervention) Details of the interventions:

Intervention intensity: eight 45‐min lectures and 15‐min discussions (to control for contact time) Mode of delivery: group sessions Co‐interventions:

| |

| Outcomes | Outcomes collected: CRQ, SF36, BAI, BDI, 6MWD and service use determined by number of hospitalisations, outpatient, mental health and emergency room visits Time points measured: 1 month, 2 months, 4 months, 8 months and 12 months Person collecting time point: not reported Outcome measures validated?: yes, with the exception of service use outcomes Missing data addressed?: Yes, ITT analysis used and authors reported that missing data at one measurement point did not prevent including the individual in the analysis | |

| Notes | Note: of 256 eligible participants, 238 were randomised but only 181 attended their first session. Study authors reported that retention in research studies at that particular facility could often be challenging with patients treated at Veteran Affairs facilities having more physical and mental health problems than the average US citizen. Also, the sample size calculation in the statistical analysis section stated that 120 participants per group would be required yet this n‐value was not met Funding: study supported by grant No IIR 00‐097 from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development, Washington DC and in part by Houston Center for Quality of Care and Utilization Studies, Office of Research and Development; and the South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Department of Veteran Affairs | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation list occurred via computer program (SAS) with blocks to provide appropriately equal numbers per class of COPD; instructor assigned treatment to the code initially by flip of coin |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The statistician provided randomisation numbers and treatment codes to the study co‐ordinator when sufficient participants for two classes had completed the baseline assessment and consented to participate; the instructor assigned the treatment to the code initially by flipping a coin |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Participants and staff performing the intervention were not blinded to treatment allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Study personnel performing assessments were blinded to treatment condition |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Missing data accounted for in regression analyses; reasons for participants' exclusion (pre‐enrolment) and attrition of participants post recruitment are reported in detail within the subject flowchart; reasons for exclusion reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Pre‐specified protocol available and no selective reporting identified |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases identified |

6MWD: Six Minute Walking Distance

BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CRQ: Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire

CSQ: client satisfaction questionnaire

DSMIV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Ed)

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second

ITT: intention‐to‐treat

MMSE: Mini‐Mental State Examination

PRIME‐MD: Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders

PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

RCT: randomised controlled trial

SGRQ: Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire

SF36: Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form 36

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Participants not diagnosed with anxiety at baseline | |

| Participants not diagnosed with anxiety at baseline (diagnosed with stress) and not COPD‐specific | |

| Participants not diagnosed with anxiety at baseline | |

| Not a RCT as defined for this review | |

| No adequate control group: co‐intervention in groups 1 and 3 was an exercise regimen, which was not a prespecified co‐intervention for this review | |

| Participants not diagnosed with anxiety at baseline. No intervention arm | |

| Participants not diagnosed with anxiety at baseline | |

| Anxiety data not reported separately | |

| Participants not diagnosed with anxiety at baseline and mean HADS scores are with normal range | |

| Progressive muscle relaxation, not psychological intervention | |

| Multi‐component intervention, more than just a psychological intervention | |

| Participants not diagnosed with anxiety at baseline | |

| Multi‐component intervention, more than just a psychological intervention |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Parallel RCT |

| Participants | N = 66 subjects with severe COPD and associated anxiety randomised Exclusion criteria: HADS‐A (anxiety) subscale score of < 8, a psychiatric diagnosis, pulmonary cancer or involvement in a different interventional trial |

| Interventions | Single psycho‐educative session in the participant's home in combination with a telephone booster session; intervention based on a manual, with theoretical foundation in CBT and psychoeducation Usual care comparator |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: HADS‐A (anxiety) and HADS‐D (depression) Secondary outcomes: CRQ and SGRQ for quality of life and mastery of dyspnoea |

| Notes | Part of a PhD project |

| Methods | Parallel RCT |

| Participants | N= 320 participants with patient‐reported functional limitations associated with COPD, and/or heart failure, with clinically significant symptoms of anxiety and/or depression Exclusion criteria: clinical factors e.g. ongoing psychotherapy, concurrent speciality mental healthcare and patient factors e.g. cognitive, bipolar, psychotic or substance abuse disorders |

| Interventions | Brief manualised CBT delivered by clinicians in comparison to usual care Intervention group: 6 weekly treatment sessions and 2 brief (10‐15‐min) telephone booster sessions within a 4‐month time frame of the ACCESS Intervention: core modules focus on increasing awareness and controlling physical and emotional symptoms and subsequently producing skills aligning with their most pressing needs; therapists used a structured manual yet could also tailor the intervention with the participant based on their needs; participant workbook also provided Control group: usual care with feedback about their depression and anxiety |

| Outcomes | Participant outcomes: depression, anxiety and physical health functioning Implementation outcomes: participant engagement, adherence and clinician brief CBT adoption and fidelity |

| Notes |

| Methods | Double‐blind RCT |

| Participants | Estimated n = 120 participants with severe to very severe COPD, motivated to participate in pulmonary rehabilitation and with sufficient mobility to attend pulmonary rehabilitation Exclusion criteria: certain co‐morbidities (e.g. unstable coronary complications, psychiatric illness), severe cognitive disability (e.g. dementia) and inability to speak Danish |

| Interventions | Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy + pulmonary rehabilitation compared to pulmonary rehabilitation only Intervention group: 8‐week manual‐based programme developed by Segal, Williams and Teasdale (2013) adjusted to the COPD population; programme delivered as an add‐on to an 8‐week standardised rehabilitation programme consisting of physical exercise and COPD‐specific patient education Control group: 8‐week standardised rehabilitation programme consisting of physical exercise and COPD‐specific patient education |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: quality of life (CAT), anxiety and depression (HADS), and BODE index Secondary outcomes: physical activity (measured by accelerometry), inflammation and oxidative stress (measured by gene expression profiling) |

| Notes |

| Methods | Parallel RCT |

| Participants | N = 312 participants with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD (FVC/FEV1 ratio < 70%, (NICE 2010); including mild‐moderate (FEV1 > 50% predicted) and severe‐very severe (< 50% predicted)), probable anxiety defined by HADSA > 8, willing to participate and provide informed consent, agreed to attend minimum of 2 and maximum of 6 CBT sessions Exclusion criteria: people with HADS‐A scores < 8, known psychosis or personality disorders, currently receiving psychological therapy including counselling or psychotherapy, unable to engage in CBT (due to cognitive impairment or dementia) and limited verbal and/or written communication problems |

| Interventions | Psychological treatment for anxiety and depression through CBT compared to self‐help leaflets Intervention group: 2‐6 sessions depending on participant need and progress as per HADS (usually involved 1 session of CBT every two weeks); components of CBT included developing a CBT formulation, psychoeducation about COPD with panic/depression, identifying/challenging negative or unhelpful thinking, identifying challenging negative or unhelpful behaviours, distraction, breathing control, relaxation, mindfulness, behavioural experiments and graded exposure Control group: self‐help leaflets |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: HADS (3 months) Secondary outcomes: HADS (6 and 12 months) |

| Notes |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | People with moderate to severe COPD |

| Interventions | CBT (4 sessions) versus usual care |

| Outcomes | Dyspnea scores |

| Notes | We have tried to contact the study authors to get more information in regards to the baseline anxiety scores of the individual participants to assess the eligibility of some of the participants for this review. We will continue intermittent attempts at contact and if no response has been received by the time of the next update, this study will be moved to the excluded category. |

| Methods | Parallel, multi‐arm RCT |

| Participants | N = 128 people attending the COPD outpatient community clinics in Perth, Western Australia were included if they had a diagnosis of COPD confirmed from medical records and screened positive for anxiety and depression Exclusion criteria: life expectancy of less than 6 months, were currently involved in another research study, had an illness exacerbation resulting in hospitalisation within the previous month, were not fluent in English, or were blind, deaf or diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease |

| Interventions | Six weeks of 2 formats of CBT, being group therapy (6‐16 people in each group) versus a self‐paced simulation‐based learning resource (DVD) compared to usual care; group therapy consisted of 2 half‐day sessions a fortnight apart and a 1‐hour telephone booster session 4 weeks later; the sessions were semi‐structured in nature and included both CBT global concepts and those that were specific to people with COPD; a manual was provided to participants for referral to CBT concepts; CBT included information about treatment rationale explaining the link between cognitions, behaviours and breathing, coping skills training, cognitive restructuring and the application and maintenance of learned coping skills; The self‐paced simulation included 6 vignettes (participants were asked to watch one per week) approximately 10 min in length on CBT skills to cope with anxiety disorders and depression, a resource manual to guide participants through the video and a weekly phone call by a researcher to check if each vignette was watched, activities completed and if participants had any questions Usual care group was under the usual treating physician; telephone follow‐up (or home visits for those with hearing difficulties) occurred at one week post‐intervention completion, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: BAI and BDI Secondary outcomes: SGRQ, absolute FEV1, FEV1 % predicted, FVC |

| Notes |

| Methods | The aim of the study was to explore the effect of behavioral intervention on the quality of life among people with COPD during the remission period |

| Participants | 54 people with COPD were randomly divided into intervention group and control group |

| Interventions | The 2 groups were treated with the same clinical therapy. The intervention group was also given a behavioral intervention that included psychological therapy with a somatic function and lifestyle intervention |

| Outcomes | All participants were evaluated with the Fang Zhong‐Jun quality‐of‐life scale pretreatment, before discharge, 3 months and 1 year after discharge |

| Notes | Results: at 1 year follow‐up, quality of life (measured as 'ability of daily life' and 'status of social activity'), psychological symptom of depression, and psychological symptom of anxiety in the intervention group (2.03 +/‐ 0.32, 2.29 +/‐ 0.77, 2.36 +/‐ 0.34, 2.07 +/‐ 0.25) were significantly lower than those in the control group (2.29 +/‐ 0.30, 2.39 +/‐ 0.41, 2.41 +/‐ 0.28, 2.16 +/‐ 0.51), (t = 2.801, 2.914, P < 0.01, t = 2.250, 2.340, P < 0.05) |

ACCESS: Adjusting to Chronic Conditions Using Eucation, Support, and Skills

BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory

BODE: Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea and Exercise capacity

CAT: COPD Assessment Text

CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CRQ: Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire

HADS‐A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ Anxiety Subscale

HADS‐D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ Depression Subscale

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second

FVC: forced vital capacity

RCT: randomised controlled trial

SGRQ: Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Telephone Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for the treatment of depression and anxiety associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial |

| Methods | Parallel RCT |

| Participants | N = 140 participants over 45 years of age, with a HADS score of > 8 and a PHQ‐9 score > 10, with a diagnosis of COPD, living in the community and able to speak English Exclusion criteria: people who commenced anti‐depressants and/or anxiolytics in the past 3 months or have had a clinically significant change in this medication in the last 3 months and deafness |

| Interventions | Telephone administered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) plus usual care Control population not specified Intervention group: starts with a face‐to‐face 50‐min session at the outpatient clinic or participant's home followed by 8 scheduled weekly telephone calls for up to 30 min in length Intervention includes behavioural strategies such as behavioural activation, activity scheduling, relaxation training, exposure hierarchies and social skills training, as well as cognitive strategies, such as cognitive restructuring, structured problem solving and behavioural experiments |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: BAI and PHQ‐9 (depression scale) Secondary outcomes: costs of illness (including medical treatment, equipment and working hours), quality of life (AQoL‐4D), client satisfaction, COPD assessment test, General Self‐Efficacy scale, Working Alliance Inventory, acute hospitalisations, number of pulmonary rehabilitation attendances |

| Starting date | February 2012 |

| Contact information | Colleen Doyle; +61 3 8387 2169; [email protected]; National Ageing Research Institute 34‐54 Poplar Rd Parkville Victoria 3052, Australia |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Randomised controlled trial of a brief telephone based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for patients with chronic lung disease and anxiety and/or depression undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation to evaluate the effect on quality of life, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and exacerbation rate |

| Methods | Parallel RCT |

| Participants | N = 100 participants with chronic lung disease, undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation and clinical or sub‐clinical anxiety or depression defined by GAI score ≥ 4/20, and/or GDS of ≥ 4/15 Exclusion criteria: inability to provide written informed consent, known psychotic disorder, cognitive impairment determined by MOCA score of < 25/30 and current enrolment in other interventional clinical trials that would potentially interfere with this study |

| Interventions | 6 CBT sessions administered by psychology interns compared to usual care Intervention group: 6 CBT sessions divided into: 2 face‐to‐face individual sessions of 1 h each, within the first 4 weeks of pulmonary rehabilitation; 4 phone sessions of 60 min each undertaken for counselling, each session will be fortnightly within the first 2 months after the face‐to‐face sessions; CBT intervention will be standardised following a manual written by the Prince Charles Hospital psychology department Control group: usual care comprised of medical treatment and pulmonary rehabilitation |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: symptoms of anxiety using GAI and depression using GDS Secondary outcomes: 6MWD, SGRQ, Asthma Quality‐of‐Life Questionnaire, Asthma Control Questionnaire, primary care and hospital health service utilisation, pulmonary rehabilitation attendance and participation assessment |

| Starting date | September 2014 |

| Contact information | A/Prof Ian Yang; +61‐7‐31395050; [email protected]; The Prince Charles Hospital Rode Road Chermside, Postcode 4032 Queensland, Australia; and Dr Marsus I Pumar; +61 04 37739874; [email protected]; The Prince Charles Hospital Rode Road Chermside, Postcode 4032 Queensland, Australia |

| Notes |

6MWD: Six Minute Walking Distance

BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory

CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder

GAI: Geriatric Anxiety Inventory

GDS: Geriatric Depression scale

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

MOCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA)

PHQ‐9: Patient Health Questionnaire‐9

SGRQ: Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

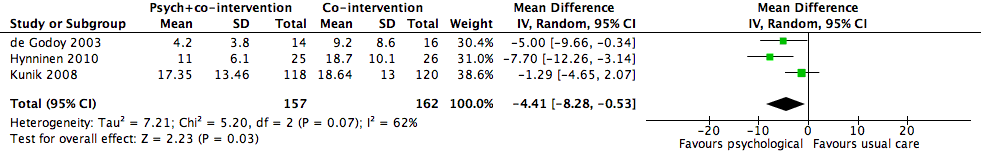

| 1 Anxiety Show forest plot | 3 | 319 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.41 [‐8.28, ‐0.53] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 1 Anxiety. | ||||

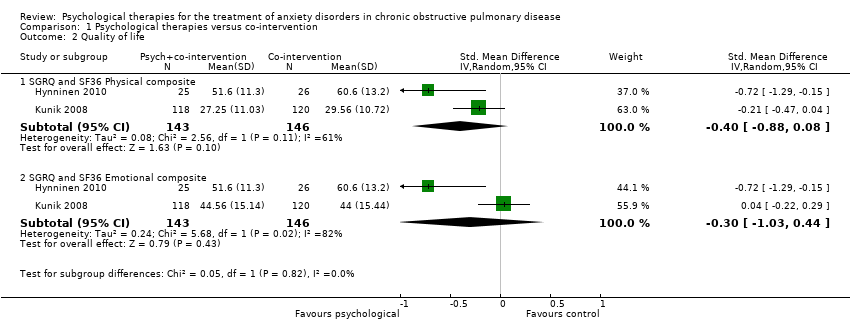

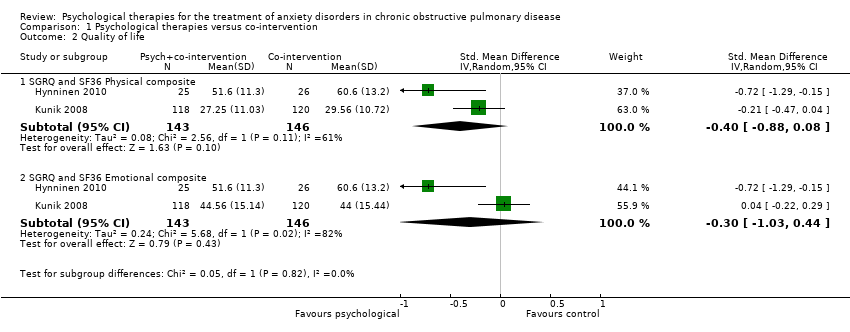

| 2 Quality of life Show forest plot | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 2 Quality of life. | ||||

| 2.1 SGRQ and SF36 Physical composite | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐0.88, 0.08] |

| 2.2 SGRQ and SF36 Emotional composite | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐1.03, 0.44] |

| 3 Six minute walking distance Show forest plot | 2 | 268 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.78 [‐58.49, 52.94] |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 3 Six minute walking distance. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

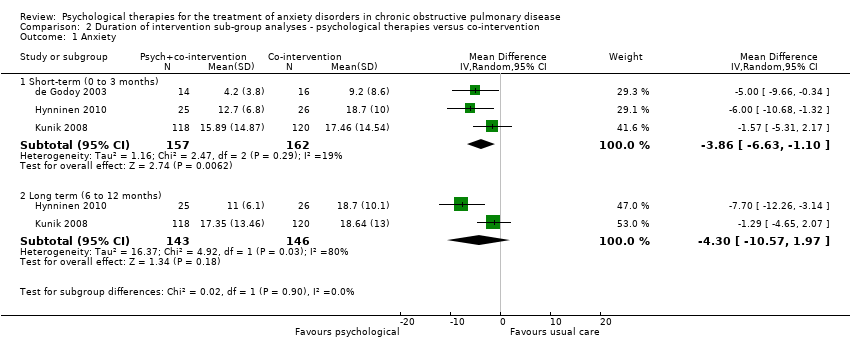

| 1 Anxiety Show forest plot | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 1 Anxiety. | ||||

| 1.1 Short‐term (0 to 3 months) | 3 | 319 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.86 [‐6.63, ‐1.10] |

| 1.2 Long term (6 to 12 months) | 2 | 289 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.30 [‐10.57, 1.97] |

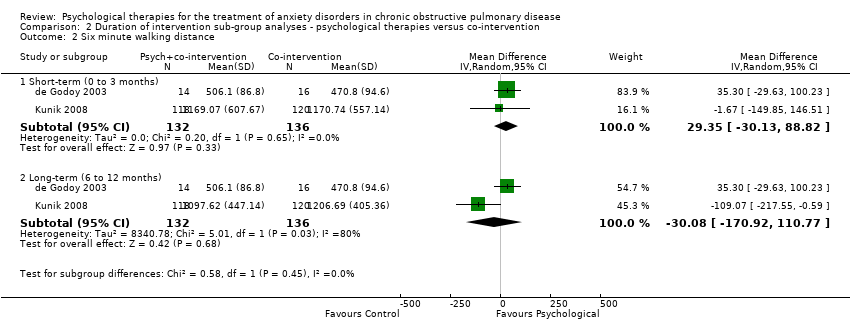

| 2 Six minute walking distance Show forest plot | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.2  Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 2 Six minute walking distance. | ||||

| 2.1 Short‐term (0 to 3 months) | 2 | 268 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 29.35 [‐30.13, 88.82] |

| 2.2 Long‐term (6 to 12 months) | 2 | 268 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐30.08 [‐170.92, 110.77] |

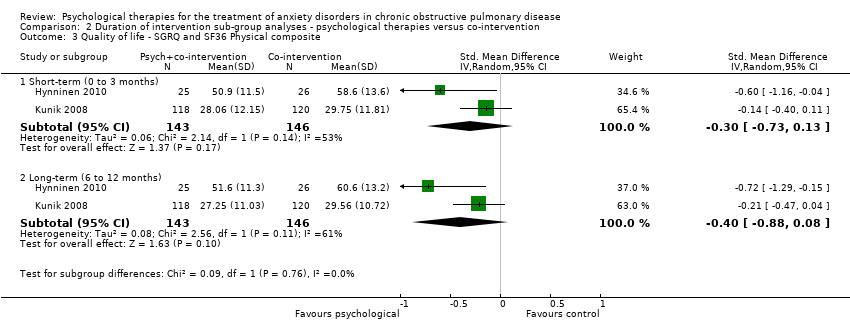

| 3 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Physical composite Show forest plot | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.3  Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 3 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Physical composite. | ||||

| 3.1 Short‐term (0 to 3 months) | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐0.73, 0.13] |

| 3.2 Long‐term (6 to 12 months) | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐0.88, 0.08] |

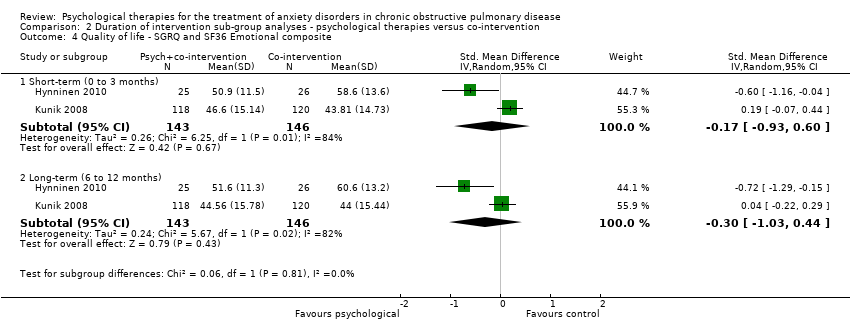

| 4 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Emotional composite Show forest plot | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.4  Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 4 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Emotional composite. | ||||

| 4.1 Short‐term (0 to 3 months) | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐0.93, 0.60] |

| 4.2 Long‐term (6 to 12 months) | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐1.03, 0.44] |

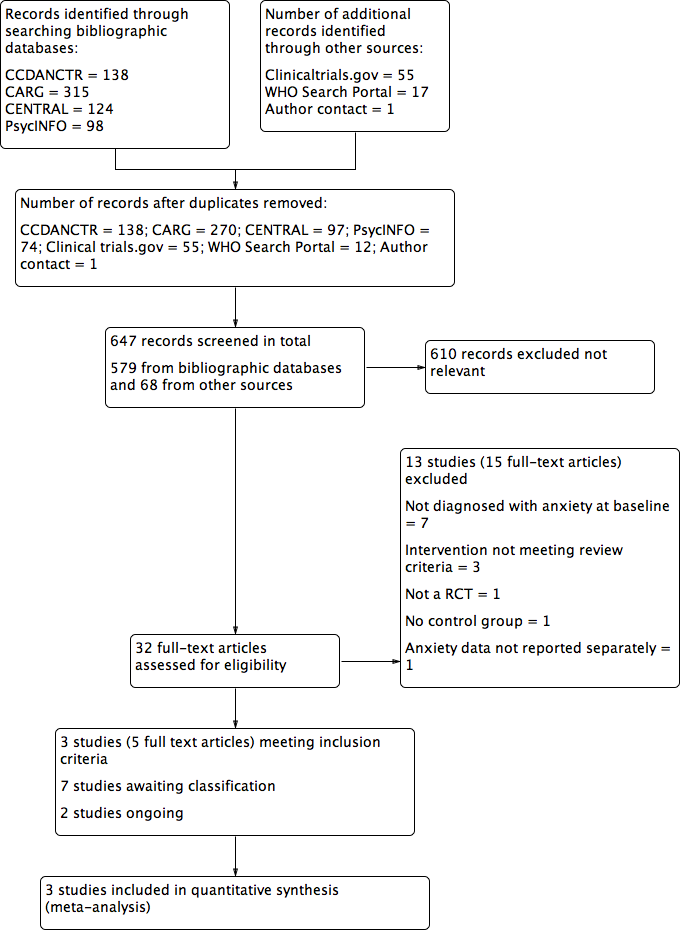

Study flow diagram

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Forest plot of comparison 1: Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, outcome: 1.1 Anxiety

Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 1 Anxiety.

Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 2 Quality of life.

Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 3 Six minute walking distance.

Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 1 Anxiety.

Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 2 Six minute walking distance.

Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 3 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Physical composite.

Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 4 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Emotional composite.

| Psychological therapies for anxiety for people with COPD | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with COPD Comparators: co‐intervention alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Psychological therapies for anxiety | |||||

| Anxiety | The mean anxiety in the control groups was | The mean anxiety in the intervention groups was | 319 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Beneficial findings were observed in favour of the psychological therapy group (p= 0.03), with levels of anxiety half that of the control population by final follow‐up (Gillis 1995) | |

| Adverse events | Study population | Not estimable | 0 | See comment | No studies reported on adverse events | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Quality of life ‐ physical composite | The mean quality of life ‐ physical composite in the control groups was | The mean quality of life ‐ physical composite in the intervention groups was | 289 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Two studies reported on quality of life with one study (Kunik 2008) reporting both SF36 and CRQ. Meta‐analysis occurred only for SF36 composite scores with SGRQ, as no totals were available for CRQ. Sub‐group analyses separating short‐term (0 to 3 months; SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.01; P = 0.06) and long‐term follow‐up (6 to 12 months; SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.53 to ‐0.06; P = 0.01) resulted in better treatment outcomes long‐term. | |

| Quality of life ‐ emotional composite | The mean quality of life ‐ emotional composite in the control groups was | The mean quality of life ‐ emotional composite in the intervention groups was | 289 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Two studies reported on quality of life with one study (Kunik 2008) reporting both SF36 and CRQ. We only meta‐analysed SF36 composite scores with SGRQ as no totals were available for CRQ. Sub‐group analyses separating short‐term (0 to 3 months; (SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.28) and long‐term follow‐up (6 to 12 months; (SMD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.32 to 0.14) resulted in better treatment outcomes long‐term. | |

| Exercise capacity | The mean exercise capacity in the control groups was | The mean exercise capacity in the intervention groups was | 268 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The Kunik 2008 study which examined 6MWD at 8 weeks (post‐intervention) and again at 12 months' follow‐up with a difference in favour of the control arm at 12 months (P = 0.05). However, authors reported that group means at beginning of the follow‐up period were not equal (P < 0.01), contributing to the spurious finding. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Substantial heterogeneity as identified via the I‐squared statistic and visual inspection of the data. | ||||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Anxiety Show forest plot | 3 | 319 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.41 [‐8.28, ‐0.53] |

| 2 Quality of life Show forest plot | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 SGRQ and SF36 Physical composite | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐0.88, 0.08] |

| 2.2 SGRQ and SF36 Emotional composite | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐1.03, 0.44] |

| 3 Six minute walking distance Show forest plot | 2 | 268 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.78 [‐58.49, 52.94] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Anxiety Show forest plot | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Short‐term (0 to 3 months) | 3 | 319 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.86 [‐6.63, ‐1.10] |

| 1.2 Long term (6 to 12 months) | 2 | 289 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐4.30 [‐10.57, 1.97] |

| 2 Six minute walking distance Show forest plot | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Short‐term (0 to 3 months) | 2 | 268 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 29.35 [‐30.13, 88.82] |

| 2.2 Long‐term (6 to 12 months) | 2 | 268 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐30.08 [‐170.92, 110.77] |

| 3 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Physical composite Show forest plot | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Short‐term (0 to 3 months) | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐0.73, 0.13] |

| 3.2 Long‐term (6 to 12 months) | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐0.88, 0.08] |

| 4 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Emotional composite Show forest plot | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Short‐term (0 to 3 months) | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐0.93, 0.60] |

| 4.2 Long‐term (6 to 12 months) | 2 | 289 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐1.03, 0.44] |