Кожные антисептики для сокращения инфекций, связанных с центральным венозным катетером

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to studies awaiting assessment

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Multicentre RCT (Switzerland) Study period: May 2002 to June 2005 Setting: 2 haematology units and 1 surgical unit in 2 university hospitals | |

| Participants | Adult patients who required a CVC. Number of participants: 400 Number of catheters; 400 Age: median age of 59 years (25% quartile of 48 to 70 years) Sex: 66% male overall | |

| Interventions | 2‐arm comparison of skin antisepsis prior to catheter insertion.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | The unit of analysis was patient, and it appeared that 1 catheter per patient was analysed although this was not stated explicitly. Funding source: the study was funded partly by the Swiss National Science Foundation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Randomisation and interventions': "The randomisation code was produced by the independent Centre for Clinical Studies using computerised random number generator… used a stratification factor and block randomisation with randomly varying block length" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Randomisation and interventions': As above, and "The randomisation was realised using closed envelopes, ensuring that the sequence was concealed before patients entered the trial." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Randomisation and interventions': "The patients, staff administering the intervention, the microbiology lab were all blinded to the assignment." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Randomisation and interventions': "The patients, staff administering the intervention, the microbiology lab were all blinded to the assignment" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Discussion, paragraph 2: "20% of the catheters were not cultured, however they were equally distributed". The absolute rate of post randomisation exclusion was high for the outcome of catheter colonisation. However, the authors appeared to follow the intention‐to‐treat principle as they analysed the patients for whom the data was available in the originally assigned group. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported all 4 major outcomes as stated in the 'Methods', namely, catheter colonisation, skin colonisation, catheter‐related BSI and adverse effects in sufficient detail in the 'Results'. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

| Methods | Multicentre RCT (Canada) Study period: Period of study not specified but authors stated that study conducted over 1 year (paragraph 1, results) Setting: hospital‐wide | |

| Participants | 'Patients and methods', 'Patients': "All patients > 18 years of age who had CVCs inserted for any purpose were eligible for inclusion in the study, provided the treating physician felt the inserted catheter would be present for a minimum of 72 hours." Number of participants: 242 Number of catheters; 374 Age: mean of 58.3 years +/‐ range of 16.8 years (chlorhexidine group ) and 62.2 years +/‐ range of 16.0 years (povidone‐iodine group) Sex: 78% male in chlorhexidine group and 72% male in povidone‐iodine group. | |

| Interventions | Comparison of 2 active agents for initial and subsequent cutaneous antisepsis for catheter care.

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Outcomes |

| |

| Notes | Funding source: the study was funded by Physicians Services Incorporated (North York, Ontario, | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Study design': Randomisation was achieved "by the use of blinded block randomisation schedule". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Although the authors stated that the block randomisation schedule was "blinded", there was no further information provided on how treatment assignment was allocated using the random sequence generated at the time of enrolment. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | The authors did not report whether blinding was achieved; blinding for clinical outcome assessment was highly unlikely because the antiseptic solutions used differed in appearance. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding for microbiological outcome assessment was unclear as this was not stated in the paper. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | For the outcomes of catheter‐related BSI and catheter colonisation, trialists only analysed 180 out of 242 patients that were initially enrolled (74%). The authors stated that 62 catheters were not analysed because the catheter tips were not available for culture, the underlying reasons of which were not provided. For the outcome of insertion site ("exit site") infection which was not dependent on catheter culture, trialists included all 242 patients in the analysis. The authors appeared to follow the intention‐to‐treat principle as they analysed the patients for whom the data was available in the originally assigned group. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported all the outcomes stated in the 'Methods' with sufficient detail in the 'Results'. |

| Other bias | High risk | The study employed a block randomisation schedule with high likelihood that blinding of participants and personnel could not be achieved. This posed a risk to the integrity of the random sequence which would be vulnerable to disruption following educated guesses by those involved in the study on the likely assigned group of the future participants. |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (Germany) Study period: May 1999 to August 2002. Setting: Inpatient hospital wards and ICUs | |

| Participants | 'Materials and methods': "Adult inpatients scheduled for elective CVC placement during normal working hours were eligible for participation in the study. Patients from normal wards as well as from the intensive care units were included. Patients known to be allergic to iodine or chlorhexidine were excluded as were all patients who needed a CVC placed under emergency conditions. No underlying disease was defined as an exclusion criteria." Number of participants: 119 Number of catheters: 200 (140 analysed) Age: mean age ranged from 50.5 to 56.6 years (SD ranged from 14.8 to 17.2 years)(reported separately according to three groups). Sex: overall 60.7% male. | |

| Interventions | Skin disinfection prior to catheter insertion and daily during the change of dressings with 1 of the 3 regimens.

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Outcomes | Catheter colonisation | |

| Notes | Funding source: not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Materials and methods': "Sealed and numbered envelopes contained the randomisation code together with the instructions for skin disinfection and forms for the documentation of the procedure." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of patients and carers not reported, although blinding appeared very unlikely because the number of antiseptic solution used for each group and their appearances were different. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | It was not stated whether the personnel taking the swabs and the interpreter of the microbiological tests were blinded to the allocation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 'Materials and methods': "In addition to the 140 catheters evaluated, 60 more catheters had been included but had to be excluded from analysis: in 5 cases, patients had died with the catheter in place, in 38 cases microbiological analysis of the catheter tip had not been performed and 17 catheters were lost during follow‐up (e.g. the patient was taken to a different clinic with the CVC in place).” In total, 200 catheters were recruited but only 140 were evaluated, which represented an overall dropout rate of 30%. It was unclear why trialists did not perform microbiological analyses in the 38 catheters as mentioned. However, the authors appeared to follow the intention‐to‐treat principle as they analysed the patients for whom the data was available in the originally assigned group. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | The only outcome stated in the 'Methods' and reported was catheter colonisation. Some important outcomes such as catheter‐related blood stream infection, clinical sepsis and mortality were not reported. |

| Other bias | High risk | There was a unit of analysis issue in which the number of catheters analysed exceeded the number of participants by nearly 18%, and the outcome was reported using catheters as the units. |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (USA) Study period: not reported Setting: no clear description of the study setting except that the study was conducted on "patients undergoing coronary artery surgery". | |

| Participants | 'Patients and methods': "60 patients scheduled for coronary artery surgery were studied during right internal jugular vein cannulation for PA catheter insertion." Number of participants: 60 Number of catheters;60 Age: not reported Sex: not reported | |

| Interventions | Comparison of 2 skin preparation regimes before insertion of CVC.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | Funding source: not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | 'Patients and methods': "Patients were assigned randomly assigned to one of two groups." There was no further information, including on random sequence generation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | There was no information in the paper to enable an assessment on whether random sequence generation was independent from allocation. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Although the authors did not explicitly say, blinding of the patient and personnel was highly unlikely because the 2 skin antisepsis regimes differed in the way of administration (1 using a liquid solution and an additional adherent film and the other using a swab without an adherent film). |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding for microbiological outcome assessment not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Authors analysed all 60 participants initially enrolled and seemed to follow the intention‐to‐treat principle. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Authors reported both major outcomes named in the 'Methods', catheter colonisation and positive glove culture, in sufficient detail in the 'Results'. However, they did not include major patient‐related outcomes such as catheter‐related BSI, sepsis or mortality. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (USA) Study period: 1986‐1987. Setting: surgical ICU | |

| Participants | All adult patients over 18 years old Number of participants:176 Number of catheters;176 Age: mean age ranged from 51 to 53 years (SD of 19 in all three groups) Sex: not reported. | |

| Interventions | Skin antisepsis prior to CVC insertion and every 48 h thereafter using 1 of 3 antiseptic solutions.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | Although not clearly stated, it appeared that each patient had only 1 catheter included in the study, as Table 1 in the article suggested. Authors studied both venous and arterial catheters and reported outcome data separately. Funding source: partly funded by Stuart Corporation (ICI, Ltd) of Wilmington, Delaware. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | 'Materials and methods', 'Procedures for insertion and care of catheters': "At the time of insertion, each catheter was randomised to one of three antiseptic solutions . . ." There was no description of random sequence generation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | 'Materials and methods', 'Source of clinical data': "Although it was not possible for the users or the research nurses to be blinded to the antiseptic agent used . . ." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | 'Materials and methods', 'Source of clinical data': "[T]he research microbiologist who processed all cultures had no knowledge of the antiseptic group to which the catheter had been assigned" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | It appeared that there were no withdrawals, as the number of catheters analysed matched the number of catheters enrolled initially. The authors appeared to follow the intention‐to‐treat principle by analysing the catheters in the originally assigned groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported both major outcomes of catheter colonisation and catheter‐related BSI as stated in the 'Methods' in sufficient detail in the 'Results'. An additional outcome of adverse event was reported, although this was reported as an overall percentage without separating venous from arterial catheters. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (France) Study period: 1 July 1992 to 31 October 1993 Setting: surgical‐trauma ICU | |

| Participants | Consecutive patients aged 18 years and above who were scheduled to receive a non‐tunnelled central venous catheter, an arterial catheter or both Number of participants: not reported Number of catheters; 158 Age: mean age from 51 to 54 years (SD 18 to 19)(reported separately in two groups) Sex: not reported | |

| Interventions | Comparison of the following 2 skin antiseptic regimens prior to catheter insertion and every 48 h post insertion.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | Trialists studied both arterial catheters and CVCs. They did not report data separately for CVC and arterial catheters except for the outcomes of catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days and catheter‐related sepsis per 1000 catheter‐days. Funding source: funded in part by Les Laboratoires Nicholas, Gaillard, France. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Materials and methods', 'Randomisation procedure': "Each patient requiring at least one catheter was randomly allocated to one of two groups by drawing envelopes from an urn." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | 'Materials and methods', 'Randomisation procedure': ""Each patient requiring at least one catheter was randomly allocated to one of two groups by drawing envelopes from an urn." It was unclear who drew the envelopes and when. It was also unclear whether the envelops were sealed and opaque. If the envelop was drawn by the investigator involved in the enrolment, there was a high risk of violating allocation concealment, for example, by redrawing. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | 'Materials and methods', 'Blood cultures': "Although it was not possible for the research team to be blinded to the antiseptic agents used, the research microbiologist who processed all cultures had no knowledge of the antiseptic group to which the catheter had been assigned." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | 'Materials and methods', 'Blood cultures': "Although it was not possible for the research team to be blinded to the antiseptic agents used, the research microbiologist who processed all cultures had no knowledge of the antiseptic group to which the catheter had been assigned." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | There was no information on post randomisation withdrawals, nor any description on the use of intention‐to‐treat analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported the major outcomes stated in the 'Methods', namely catheter colonisation and catheter related sepsis, in sufficient details in the 'Results'. The authors provided separate data for CVCs and arterial catheters for the outcomes of catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days and catheter‐related sepsis per 1000 catheter‐days. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (France) Study period: 14 May 2004 to 29 June 2006 Setting: surgical ICU | |

| Participants | Adult inpatients Number of participants: not reported Number of catheters; 538 Age: mean age 57‐58 years (SD 18‐19) (reported separately in two groups) Sex: 67.4% men in chlorhexidine group and 75.7% men in povidone‐iodine group. | |

| Interventions | Skin antisepsis using the following 2 regimens prior to CVC insertion and thereafter every 72 h.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | Funding source: this study was supported by Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire de Poitiers and unrestricted grants from Bayer HealthCare and Viatris Pharmaceuticals. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Randomisation': "The randomisation sequences were generated by computer and conveyed to the investigators by means of sealed envelopes, 1 for each catheter, with instructions to select envelopes in numerical order." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Randomisation': "The randomisation sequences were generated by computer and conveyed to the investigators by means of sealed envelopes, 1 for each catheter, with instructions to select envelopes in numerical order." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | 'Methods', 'Randomisation': "Although it was not possible for the nurses and attending physicians to be blinded to the antiseptic agent used because of different colours of the 2 solutions (brown for the povidone‐iodine and colourless for the chlorhexidine‐based solution), the microbiologists who processed all of the cultures and the research team who reviewed the outcomes were unaware of the type of antiseptic solution used." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Randomisation': "Although it was not possible for the nurses and attending physicians to be blinded to the antiseptic agent used because of different colours of the 2 solutions (brown for the povidone‐iodine and colourless for the chlorhexidine‐based solution), the microbiologists who processed all of the cultures and the research team who reviewed the outcomes were unaware of the type of antiseptic solution used." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | There was 11% withdrawal, with a similar number of catheters excluded from analysis from the 2 groups. The authors have clearly stated the reasons for withdrawal and appeared to follow the intention‐to‐treat principle by analysing the available patient data in the originally assigned groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported the 2 major outcomes stated in the 'Methods', namely, catheter colonisation and catheter‐related BSI, in sufficient details in the 'Results'. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (USA) Study period: not reported Setting: hospital departments of General Surgery (123), Medicine (20), Thoracic Surgery (19), Neurosurgery (8), Obstretrics and Gynaecology (3), Paediatrics (3) and others (3) | |

| Participants | All hospital inpatients who required a CVC Number of participants: 159 adults, 3 children Number of catheters; 179 Age: not reported Sex: not reported | |

| Interventions | Skin antisepsis applied daily after CVC insertion.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | Funding source: supported in part by the Purdue Frederick Company, Wilmington, Delaware. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | The exact method of sequence generated was not described. However, in the 'Methods', the authors stated that patients were randomised according to hospital registration number, suggesting that they used alternation, instead of true randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | As above |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Although the authors did not explicitly say, it was unlikely that the participants and the care providers were blinded, as the study assessed skin antisepsis versus no skin antisepsis. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding of microbiological outcome assessor not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Although the authors did not describe any withdrawals, it appeared that all catheters that were initially enrolled were analysed in the originally assigned groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported the major outcomes of catheter colonisation and catheter‐related BSI as stated in the 'Methods' in sufficient detail in the 'Results'. The authors also reported an additional outcome of skin erythema. However, this was reported as an overall percentage of patients with colonised catheters, not according to the allocated groups, and so it did not allow data extraction for meta‐analysis. Nevertheless, this did not affect our judgment on the overall risk of reporting bias in any major way. |

| Other bias | High risk | There was a unit of analysis issue in which the number of catheters analysed exceeded the number of participants by nearly 10%, and the outcomes were reported using catheters as the units. |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (USA) Study period: November 1982 to December 1985 Setting: surgical ICU | |

| Participants | Adult burn patients with a CVC in place Number of participants: 50 Number of catheters; 50 Age: mean age of 5.4 years (10 weeks to 15 years) Sex: 68% male | |

| Interventions | Skin antisepsis prior to catheter removal:

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | Funding source: not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | 'Materials and methods': Patients were "randomly assigned to one of two groups". Method of random sequence generation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Although not stated in the article, blinding appeared highly unlikely because the intervention involved an additional measure in catheter site care. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding of microbiological outcome assessor not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Although not clearly stated, it appeared that all 50 patients were analysed in their originally assigned groups as the tabulated results suggest. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | There were 2 major outcomes reported, namely, catheter colonisation (positive catheter tip culture) and positive blood culture. However, the data from positive blood culture was unsuitable to be included in the meta‐analysis as it was reported only as an overall figure and not according to the allocated groups. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (Finland) Study period:not reported. Setting: ICU | |

| Participants | Adult inpatients admitted to ICU who required a CVC. No exclusion criteria stated Number of participants:136 Number of catheters; 136 (124 analysed) Age: not reported Sex: not reported | |

| Interventions | Skin antisepsis applied prior to CVC insertion and regularly thereafter.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | No adverse effects were recorded in either group, so we do not include the data in our analysis. Funding source: not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Patients and methods': The patients were "randomly allocated to one of two groups". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not adequately described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Not stated in the paper, but blinding appears unlikely as the trial involved a comparison between the application of chlorhexidine‐soaked gauze versus a dry sterile gauze. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding of microbiological outcome assessor not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | The authors did not provide information on the initial number of patients and catheters recruited or the eventual number analysed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The outcomes were not defined in the 'Methods'. However, authors reported all major outcomes, including septicaemia, catheter colonisation and adverse effects, in sufficient detail. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (Spain) Study period: 1 Jan 2005 to 3 June 2006 Setting: adult medical‐surgical ICU in a university hospital | |

| Participants | Patients requiring a CVC Number of participants: 420 Number of catheters; 998 (631 analysed) Age: mean age from 60 to 61 years (SD 16‐17) (reported separately in three groups) Sex: not reported. | |

| Interventions | 3‐arm comparison of the following skin antiseptic regimens applied prior to CVC insertion and every 72 h thereafter.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | Funding source: not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Study design': The random sequence was generated by "[b]y use of a blinded block randomisation schedule" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not adequately reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Although not stated by the authors, blinding to patients and caregivers appeared highly unlikely, as the antiseptic solutions used differed in appearance. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | 'Methods', 'Bacteriologic methods': "The microbiologists who performed the catheter‐tip cultures had no knowledge of the antiseptic group to which the catheter had been assigned." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Authors excluded from analysis 367/998 (36.7%) of the catheters initially randomised for various reasons (Figure 1 of the paper). They excluded 279 catheters post enrolment because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. However, among these excluded catheters, the reason given for 179 of them was that they were "not cultured". It was unclear what the underlying reasons were for failure to obtain culture in these catheters, and whether the excluded data here were missing at random. Trialists excluded 88 further catheters because they were inserted beyond 72 h after discharge from ICU. These 88 catheters were evenly distributed among the 3 assigned groups (61 between the 2 chlorhexidine groups and 27 in the povidone‐iodine group). However, following the construction of the best‐ and worst‐case scenarios using the dropouts, the direction of the effect estimates swung from significantly favouring the chlorhexidine group (best‐case scenario for chlorhexidine group) to significantly favouring the povidone‐iodine group (worst‐case scenario for chlorhexidine group). It was unclear whether the authors followed the intention‐to‐treat principle by analysing all available data according to the originally assigned groups, as there was no mention of participants who crossed over to the other group. We accorded the study high risk in this domain due to the high absolute dropout rate including the 179 catheters that were not adequately accounted for, as mentioned above, and the vulnerability of the result estimates to best‐ and worst‐case scenarios. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported all 3 outcomes stated in the 'Methods', namely, catheter colonisation, catheter‐related BSI ("catheter‐related sepsis") and catheter‐related bacteraemia in sufficient detail in the 'Results'. In addition, they also reported the important outcome of mortality in the "Patient characteristics" table. although this was not a pre‐specified outcome in the methods.. |

| Other bias | High risk | The study employed a block randomisation schedule with high likelihood that blinding of participants and personnel were not achieved. This posed a risk to the integrity of the random sequence, which would be vulnerable to disruption following educated guesses by those involved in the study on the likely assigned group of the future participants. There was a serious unit of analysis issue in which the number of catheters analysed exceeded the number of participants by over 50%, and the major outcomes were reported using catheters as the units. |

| Methods | Multicentre RCT (Japan) Study period: March 2014 (not further details provided) Setting: 23 Japanese ICUs | |

| Participants | 'Participants': "Patients over 18 years of age undergoing CVC and AC placement for more than 72 hours" Number of participants:not reported Number of catheters; 137 Age: not reported Sex: not reported | |

| Interventions | 3‐arm comparison for skin antisepsis prior to catheter insertion.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | For this review, we combined the data for 1% CHG and 0.5% CHG as there was no significant difference in the results between the 2 groups. This was an interim analysis of the full study and was published in abstract form. Funding source: not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned in the published abstract |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned in the published abstract |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned in the published abstract |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned in the published abstract |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned in the published abstract |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned in the published abstract |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information in the published abstract to assess the risks of bias |

| Methods | Single‐centre RCT (Iran) Study period: not reported. Setting: cardiac‐surgical ICU | |

| Participants | Adult patients admitted to ICU after cardiac surgery Number of participants: 249 Number of catheters; 249 Age: mean age of 57 and 60 years (range 51 to 68) (reported separately in two groups) Sex: 76.1% and 76.5% male (reported separately in two groups) | |

| Interventions | Skin antisepsis prior to CVC insertion.

| |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes assessed at various points during in‐patient stay. | |

| Notes | The number of CVCs evaluated matched the number of participants. Funding source: not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | From the authors' description, it appeared that an alternate sequence was used following an initial coin toss to determine the daily order of the grouping. 'Methods': "[A]ll the patients were separated into the intervention and control groups based on simple randomisation and entry sequence to the pre‐operation room. Each day, a simple coin randomisation technique was used to determine the group for the first patient and the spraying of pure water or Sanosil 2% on the catheter location (from the upper chest to the mandible). Subsequently, odd and even numbers were used to determine the group of the other patients." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | From the authors' description, it appeared that an alternate sequence was used following an initial coin toss to determine the daily order of the grouping. 'Methods': "[A]ll the patients were separated into the intervention and control groups based on simple randomisation and entry sequence to the pre‐operation room. Each day, a simple coin randomisation technique was used to determine the group for the first patient and the spraying of pure water or Sanosil 2% on the catheter location (from the upper chest to the mandible). Subsequently, odd and even numbers were used to determine the group of the other patients." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | From the authors' description, it appeared that the patients and the person who removed the catheters to send for culture were blinded (see below). However, the authors did not state whether the nurse who sprayed the study substance was blinded to the study materials. 'Methods': "Both spray bottles were similar in shape and cover. Sanosil does not have any colour or smell and is similar to water, and the patients were blinded to the study." 'Methods': "Each day, two trained ICU nurses, blinded to the group type of the patients, collected the tips of five removed catheters aseptically..." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | It appeared that all patients recruited initially had their CVCs analysed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Authors reported the 2 key outcomes specified in the 'Methods', namely, catheter colonisation and sepsis, in the 'Results'. As no patient in either group developed sepsis, we did not include this outcome in our meta‐analysis. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified |

AC: arterial catheter; BSI: bloodstream infection; CHG: chlorhexidine‐gluconate; CVC: central venous catheter; ICU: intensive care unit; PA: pulmonary artery; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Before‐and‐after study. Basis of exclusion: design | |

| Quasi‐experimental before‐and‐after study. Basis of exclusion: design | |

| A commentary to Parienti 2004. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| An RCT that assessed ExSept versus chlorhexidine for patients with haemodialysis catheters. Basis of exclusion: population | |

| Non‐randomised trial that assessed CVC site care using 2% chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone‐iodine. Basis of exclusion: design | |

| This is a conference abstract of an study awaiting classification (BIlir 2013) | |

| A review article on infection control strategies for the newborn. Basis of exclusion: article type and population | |

| A before‐and‐after study that assessed a multifaceted programme in decreasing blood culture contamination. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| Cross‐over study that assessed chlorhexidine‐impregnated foam dressing for prevention of catheter‐related BSI in patients undergoing haemodialysis. Basis of exclusion: design, population and intervention | |

| RCT that compared maximal sterile barrier (consisting of mask, cap, sterile gloves, gown, large drape) versus control precautions (mask, cap, sterile gloves, small drape) and transparent polyurethane film versus gauze dressing for reduction of CVC‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A single‐centre RCT (UK) that compared the PosiFlow needleless connector against the standard luer cap attached to the CVCs for adult patients admitted for cardiac surgery. The authors used a factorial design which enabled the concurrent 3‐arm comparison of 3 different skin antiseptic solutions (0.5% chlorhexidine/alcohol, 70% isopropyl alcohol and 10% povidone–iodine) applied prior to the insertion of the catheters. However, the major outcome assessed was "stopcock entry port microbial contamination" rather than catheter colonisation, and this is not part of the prespecified outcomes in our review. Basis of exclusion: study design (design of the outcome) | |

| RCT that compared a needless connector set (Clearlink Y‐type extension set) against standard 3‐way stopcocks with caps for reducing CVC related infections. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A review article on reducing catheter‐related infections in the ICU. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| Cost‐effectiveness analysis on chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone‐iodine for catheter site care. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| Cost‐benefit analysis of chlorhexidine gluconate dressing in reducing catheter‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| RCT that assessed antibiotic flush for CVCs in children with cancer. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A review article on strategies to prevent catheter‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| A review article on strategies to prevent catheter‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| A cross‐over study that compared the use of chlorhexidine solution against chlorhexidine‐impregnated cloth for CVC care. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| A quasi‐randomised trial in which patients were assigned on an alternate basis to either octenidine‐based skin antiseptic solution versus propanol‐based solution. Additionally, the results were presented in 25th centile, median and 75th centile of quantitative skin culture (in CFU/24 cm2) which does not allow extraction for meta‐analysis. Basis of exclusion: study design and data reporting | |

| A prospective non‐randomised study that assessed catheter‐related infections following the introduction of various infection control strategies. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| RCT that assessed chlorhexidine gluconate gel dressing versus chlorhexidine gluconate disk in reducing CVC‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A quasi‐experimental study comparing 2 skin antisepsis regimens (chlorhexidine and povidone‐iodine) and 2 types of dressing (Tegaderm and standard gauze) in a 4‐arm comparison of different combinations. The authors only reported the results in F or X2 values along with the P values, without reporting the raw data, which precluded data extraction for meta‐analysis. Basis of exclusion: study design and data reporting | |

| A non‐randomised study with historical cohort that assessed povidone‐iodine ointment in addition to dressing in reducing CVC‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| A non‐randomised study that assessed the effect of chlorhexidine scrub of the CVC hub during each access in reducing CVC‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| A multicentre observational study that evaluated CVC‐related infections in children. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| A before‐and‐after study that evaluated the effect of a hand hygiene promotion programme in reducing infections in an ICU. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| An RCT that assessed the local reaction to a chlorhexidine gluconate‐impregnated antimicrobial dressing in very low birth weight infants. Basis of exclusion: population and intervention | |

| An RCT that compared chlorhexidine gluconate‐impregnated dressing with povidone‐iodine skin scrub for prevention of CVC‐related infections in neonates. Basis of exclusion: population | |

| An RCT that compared chlorhexidine gluconate with povidone‐iodine as skin antisepsis prior to CVC placement in neonates. Basis of exclusion: population | |

| An RCT that assessed the safety of chlorhexidine gluconate in neonates with percutaneously inserted central venous catheters. Basis of exclusion: population | |

| A review article on prevention of catheter‐related BSI in the neonatal intensive care setting. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| A longitudinal cohort study that compared two CVC cleaning protocols (containing alcohol‐based povidone‐iodine solution (Betadine alcolique) and chlorhexidine‐based antiseptic (Biseptine), respectively) administered in different periods. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| A prospective, non‐randomised study that evaluated the effect of multiple infection control strategies in reducing catheter‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| A non‐randomised trial that compared antiseptic‐impregnated CVC with peripherally‐inserted central line in reducing catheter‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: study design and intervention | |

| A commentary on an included study (Yousefshahi 2013) | |

| A review article on prevention of catheter‐related infection in long‐term catheters. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| An RCT that evaluated the effect of povidone‐iodine connection shield that is incorporated in the catheter hub in reducing CVC‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| An RCT that assessed the effect of chlorhexidine dressing in reducing catheter colonisation. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| An RCT that assessed the effect of mupirocin ointment on colonisation rate of internal jugular vein catheters. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A retrospective study that assessed the effect of multiple infection control measures on the rates of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in an adult ICU. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| An RCT that assessed occlusive versus non‐occlusive right atrial catheter dressing change procedures in children with cancer. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| An RCT comparing maximal sterile barrier precaution versus standard sterile barrier precaution measures during CVC insertion in reducing CVC‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A non‐randomised trial that compared the use of chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine for CVC site skin disinfection in 2 separate cohorts of patients. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| An RCT that compared honey versus mupirocin applied at the catheter exit site for preventing catheter‐related infections in patients undergoing haemodialysis. Basis of exclusion: population and intervention | |

| An RCT that evaluated the absorption of silver in very low birthweight infants who received silver alginate‐impregnated central venous catheter. Basis of exclusion: population and intervention | |

| A conference abstract that reports the impact of simulation training on residents' performance in adhering to maximum sterile barrier precaution during CVC insertion. Basis of exclusion: research question and design | |

| A national survey on measures to reduce catheter‐related BSI. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| This is a commentary on an included study (Mimoz 1996). Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| An RCT that compared the use of 10% povidone‐iodine versus 2% chlorhexidine for skin disinfection prior to insertion of epidural or central venous catheters. The study combined both epidural and CVCs is the outcome reporting with no separate data for CVC, and more importantly, the outcome of skin colonisation was assessed based on a skin swab that was taken immediately after the application of the skin antiseptic agent, which did not fit in with our question of whether the application of skin antiseptic agent reduces catheter‐related infection during the period of catheter use. Excluded on th basis of research question and design | |

| A non‐randomised trial that assessed a multifaceted strategy in CVC management in reducing catheter‐related infection in children with chronic illness. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| An RCT comparing transparent dressing versus a dry gauze applied at the exit site of the catheter on haemodialysis patients. Basis of exclusion: population and intervention | |

| An RCT comparing alcohol‐chlorhexidine against povidone‐iodine for skin antisepsis for intravascular catheters. The study evaluated a mixture of venous, arterial and Swan Gantz catheters with no separate outcome reporting for venous catheters. There were no contact details provided in the paper to request for separate data for venous catheters. Basis of exclusion: insufficient information | |

| An RCT that assessed the effectiveness of chlorhexidine gluconate‐impregnated dressing in reducing catheter‐related infections in children. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| An RCT comparing 2 different dressings for arterial and venous catheters in reducing catheter‐related infections. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A prospective cohort study that evaluated the effect of catheter manipulation on catheter‐related BSI in neonates. Basis of exclusion: study design, population and intervention | |

| A commentary on disinfectant for vascular catheters. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| An RCT comparing different antibiotic ointments for preventing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A pilot RCT involving in 3 Irish outpatient hemodialysis units compared 2% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) in 70% isopropyl alcohol with CHG solutions for central venous catheter exit site antisepsis. Basis of exclusion: population. | |

| A prospective cohort study that evaluated the rates of catheter‐related BSI over 3 study periods: pre‐intervention (phase 1), in which all patients were bathed with soap and water or non‐medicated washcloths; active intervention (phase 2), in which patients were bathed with 2% chlorhexidine gluconate cloths with the number of baths administered and skin tolerability assessed; and post‐intervention (phase 3), in which chlorhexidine bathing continued but without oversight by research personnel. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| A non‐randomised study that evaluated a step‐wise infection control approach in reducing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: study design, intervention | |

| A non‐randomised study that evaluated the use of daily chlorhexidine bath in reducing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| An RCT comparing transparent polyurethane and hydrocolloid dressings for CVC in reducing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A cluster‐RCT that assessed the effects of daily chlorhexidine bathing on the rates of healthcare associated infection in general for all ICU patients, not specific to patients with CVC in place. Basis of exclusion: population | |

| A cluster‐randomised cross‐over study that assessed the effectiveness of alcoholic povidone‐iodine in preventing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| An evidence‐based summary on the effectiveness of chlorhexidine versus 70% alcohol for CVC injection cap disinfection. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| An RCT that assessed the effectiveness of maximal sterile precaution during CVC insertion in reducing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A cluster‐randomised trial that assessed the effectiveness of 2 multifaceted infection control projects in reducing central line infections. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| An RCT that assessed the effectiveness of mupirocin ointment in reducing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A commentary on Parienti 2004. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| An RCT that assessed the effectiveness of changing intravenous administration set for reducing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| An RCT that assessed the use of full sterile barrier precaution in reducing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| A review article on measures to reduce catheter‐related infection during insertion of CVC. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| A non‐randomised, comparative, cross‐over trial that evaluated the effectiveness of alcohol‐based hand gel in reducing hospital‐acquired infections. Basis of exclusion: research question, study design | |

| An RCT that assessed the effectiveness of chlorhexidine‐impregnated wound dressing in reducing CVC‐related infection in patients undergoing chemotherapy. Basis of exclusion: intervention | |

| An economic analysis on chlorhexidine‐impregnated sponges for reducing catheter‐related infection. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| An article identified through a related review paper in the form of a conference abstract. The text of the conference abstract could not be traced after contacting the author of the review article. We were unable to locate the contact details of the authors of this conference paper to request for further information. The conference abstract did not appear to be published subsequently in full. Basis of exclusion: insufficient information | |

| A review article comparing central venous line and arterial line infections. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| A cluster‐RCT that compared chlorhexidine bathing versus soap and water bathing in decreasing the rates of healthcare associated infection for all patients in ICUs, and not only patients with a CVC in place. Basis of exclusion: population | |

| A prospective observational study that assessed the effectiveness of octenidine hydrochloride for CVC site care in patients receiving bone marrow transplant. Basis of exclusion: study design | |

| An evidence‐based summary that examined the role of chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine antisepsis for reducing catheter‐related infection in neonates. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| An overview on catheter‐related BSI. Basis of exclusion: article type | |

| A before‐and‐after study that assessed the effectiveness of an educational programme on promoting hand hygiene measures in reducing catheter‐related BSI. Basis of exclusion: study design |

BSI: bloodstream infection; CFU: colony‐forming units; CVC: central venous catheter; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT (Czech Republic) |

| Participants | Adult surgical patients who required a CVC |

| Interventions | CVC insertion site disinfection with 10% povidone‐iodine (Poviiodeks) versus Savlosol (15% cetrimide, 1.5% chlorhexidine‐gluconate, ethanol) |

| Outcomes | Catheter colonisation and catheter‐related BSI |

| Notes | — |

| Methods | RCT (Turkey) |

| Participants | Adult ICU patients who required a CVC |

| Interventions | 3‐arm comparison: skin antisepsis using 4% chlorhexidine gluconate (n = 19), 10% povidone iodine (n = 19) or octenidine hydrochlorodine (n = 19) |

| Outcomes | Catheter colonisation and catheter‐related BSI ("catheter‐related sepsis"), determined using "standard microbiological methods" ('Materials and methods') |

| Notes | The study evaluated a mixture of venous and arterial catheters with no separate analysis for venous catheters. This appears to be a conference abstract. We are awaiting further information from the authors. |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Surgical patients who required a CVC |

| Interventions | Transparent occlusive dressing versus daily CVC site care with povidone‐iodine 10% solution |

| Outcomes | Catheter colonisation and catheter‐related sepsis |

| Notes | Awaiting full text |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | Unclear |

| Interventions | 1% chlorhexidine plus 75% alcohol versus 10% povidone iodine for cutaneous disinfection and follow‐up site care with central venous and arterial catheters |

| Outcomes | Catheter colonisation and catheter‐related BSI |

| Notes | This title was identified as a conference abstract from an earlier meta‐analysis on a similar topic. There is no further information at this stage other than the title. The author of the meta‐analysis paper with the title could not locate the abstract paper, and the study appeared not to be subsequently published in full. The study included both venous and arterial catheters, and it was unclear whether a separate outcome report for venous catheters would be available. We are awaiting the response of the study author for further information. |

| Methods | Open‐label multi‐centre RCT with a two‐by‐two factorial design |

| Participants | Adults (age >/=18 years) admitted to one of 11 French intensive‐care units and requiring at least one of central‐venous, haemodialysis, or arterial catheters |

| Interventions | All intravascular catheters prepared with 2% chlorhexidine‐70% isopropyl alcohol (chlorhexidine‐alcohol) or 5% povidone iodine‐69% ethanol (povidone iodine‐alcohol), with or without scrubbing of the skin with detergent before antiseptic application |

| Outcomes | "catheter‐related infections", catheter colonisation, adverse effects |

| Notes | Awaiting full‐text report for specific information on central venous catheters |

| Methods | A comparative study (it is unclear from the abstract whether it is an RCT) |

| Participants | Haematology patients (age range unclear) |

| Interventions | 1% chlorhexidine‐gluconate ethanol versus 10% povidone‐iodine for skin antisepsis of CVC sites |

| Outcomes | Catheter‐related BSI, catheter colonisation |

| Notes | Awaiting full text from the authors |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Comparison of four skin preparation strategies to prevent catheter‐related infection in intensive care unit (CLEAN trial): a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial |

| Methods | "A prospective multicenter, 2 × 2 factorial, randomized‐controlled, assessor‐blind trial" |

| Participants | Setting: 11 intensive care units in 6 French hospitals. Participants: All adult patients aged over 18 years requiring the insertion of 1 or more of the following: peripheral arterial catheter, non‐tunnelled central venous catheter, haemodialysis catheter and arterial pulmonary catheter |

| Interventions | Patients are allocated to 1 of the 4 skin preparation strategies: 2% chlorhexidine/70% isopropyl alcohol or 5% povidone iodine/69% ethanol, with and without prior skin scrubbing |

| Outcomes | Catheter‐related BSI, catheter colonisation, cutaneous tolerance, length of hospitalisation, mortality and cost. |

| Starting date | October 2012, lasting approximately 14 months |

| Contact information | Corresponding author: Olivier Mimoz o.mimoz@chu‐poitiers.fr |

| Notes | Clinicaltrials.gov number NCT01629550. Protocol published in Trials, 2013:14: 114 |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

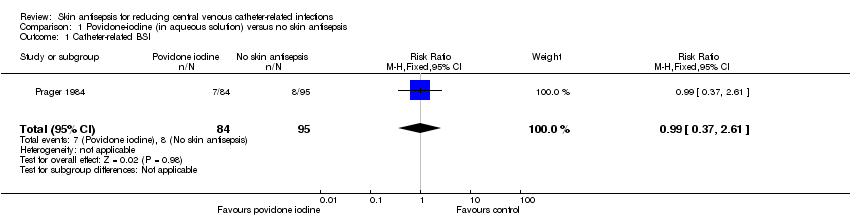

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 1 | 179 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.37, 2.61] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI. | ||||

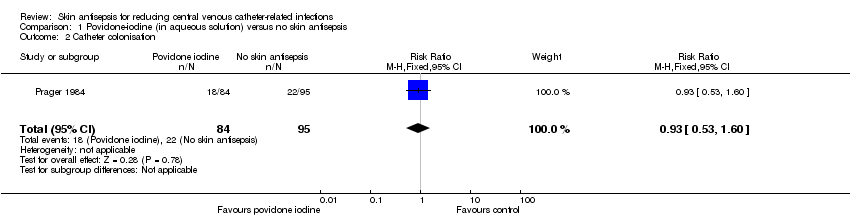

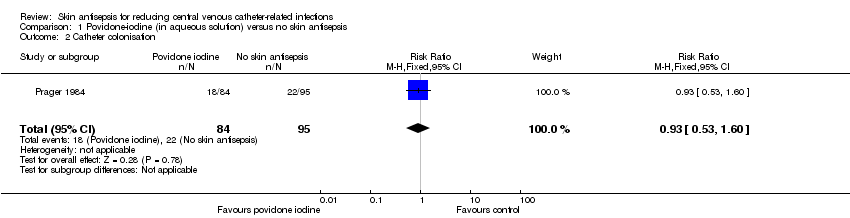

| 2 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 179 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.53, 1.60] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

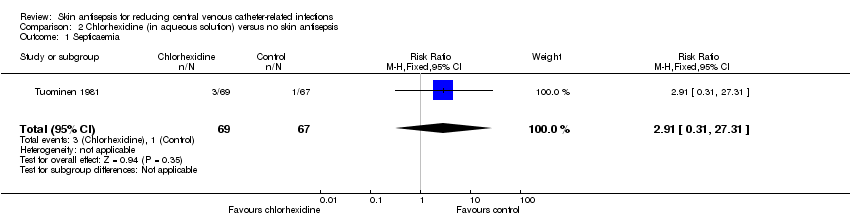

| 1 Septicaemia Show forest plot | 1 | 136 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.91 [0.31, 27.31] |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 1 Septicaemia. | ||||

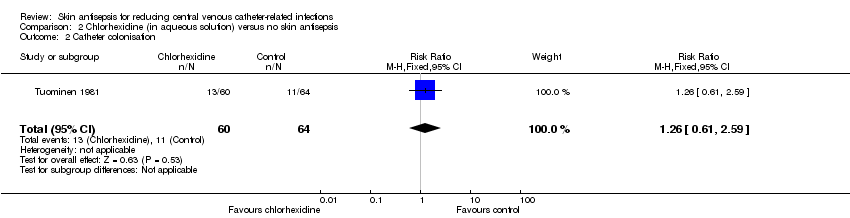

| 2 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.61, 2.59] |

| Analysis 2.2  Comparison 2 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

| 3 Number of patients who required antibiotics during in‐dwelling period of catheter Show forest plot | 1 | 136 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.55, 1.27] |

| Analysis 2.3  Comparison 2 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 3 Number of patients who required antibiotics during in‐dwelling period of catheter. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

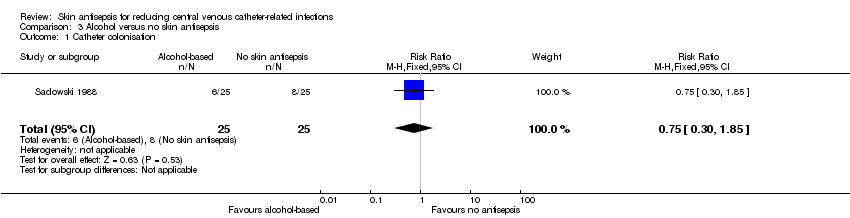

| 1 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.30, 1.85] |

| Analysis 3.1  Comparison 3 Alcohol versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 1 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 4 | 1436 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.41, 0.99] |

| Analysis 4.1  Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI. | ||||

| 1.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 2 | 452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.32, 1.28] |

| 1.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 2 | 503 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.39, 1.53] |

| 1.3 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | 1 | 481 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.13, 1.24] |

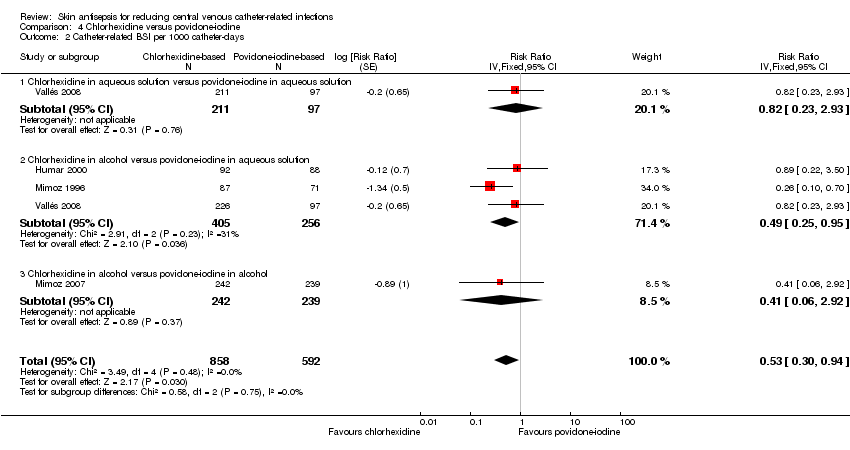

| 2 Catheter‐related BSI per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 4 | 1450 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.30, 0.94] |

| Analysis 4.2  Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 2 Catheter‐related BSI per 1000 catheter‐days. | ||||

| 2.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 1 | 308 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.23, 2.93] |

| 2.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 3 | 661 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.25, 0.95] |

| 2.3 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | 1 | 481 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.06, 2.92] |

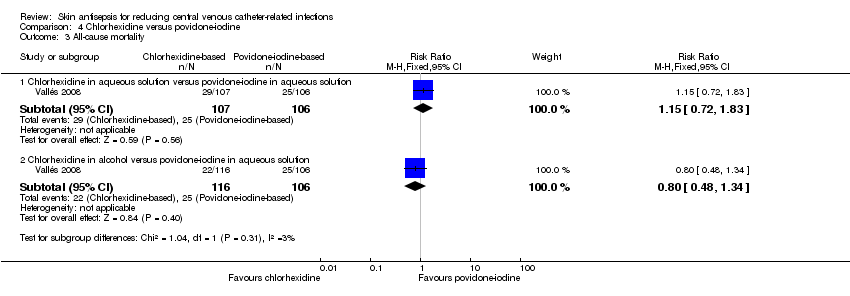

| 3 All‐cause mortality Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 4.3  Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 3 All‐cause mortality. | ||||

| 3.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 1 | 213 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.72, 1.83] |

| 3.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 1 | 222 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.48, 1.34] |

| 4 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 5 | 1533 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.12, ‐0.03] |

| Analysis 4.4  Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 4 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

| 4.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 2 | 452 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.09 [‐0.17, ‐0.02] |

| 4.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 3 | 600 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.11, 0.03] |

| 4.3 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | 1 | 481 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.17, ‐0.04] |

| 5 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 5 | 1547 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.50, 0.81] |

| Analysis 4.5  Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 5 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days. | ||||

| 5.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 1 | 308 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.40, 1.20] |

| 5.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 4 | 758 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.48, 0.85] |

| 5.3 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | 1 | 481 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.24, 1.17] |

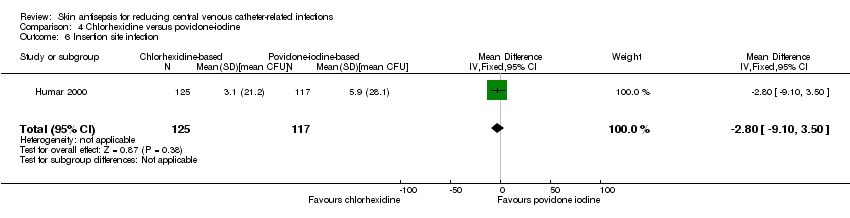

| 6 Insertion site infection Show forest plot | 1 | 242 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.80 [‐9.10, 3.50] |

| Analysis 4.6  Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 6 Insertion site infection. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

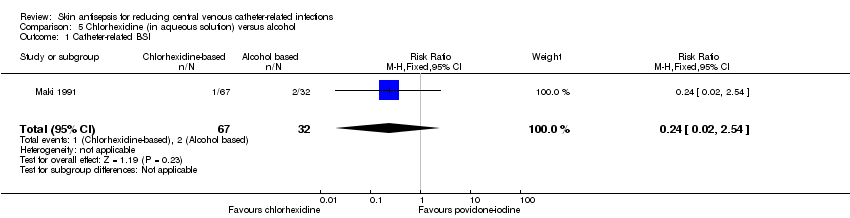

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.02, 2.54] |

| Analysis 5.1  Comparison 5 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus alcohol, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI. | ||||

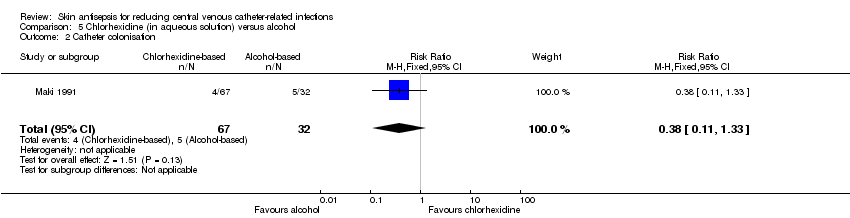

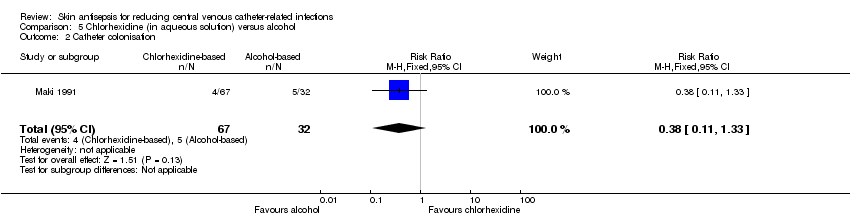

| 2 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.11, 1.33] |

| Analysis 5.2  Comparison 5 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus alcohol, Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

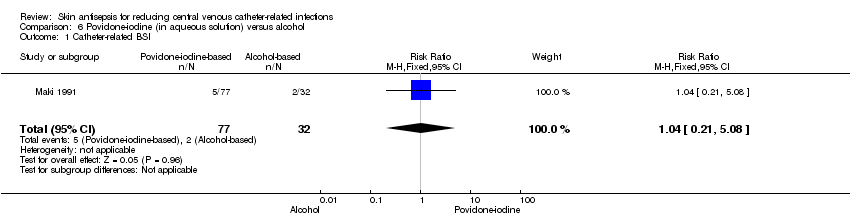

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 1 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.21, 5.08] |

| Analysis 6.1  Comparison 6 Povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus alcohol, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI. | ||||

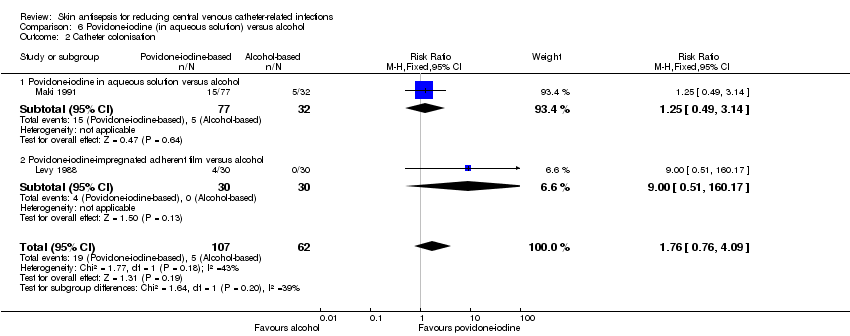

| 2 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 2 | 169 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [0.76, 4.09] |

| Analysis 6.2  Comparison 6 Povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus alcohol, Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

| 2.1 Povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution versus alcohol | 1 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.49, 3.14] |

| 2.2 Povidone‐iodine‐impregnated adherent film versus alcohol | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.0 [0.51, 160.17] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

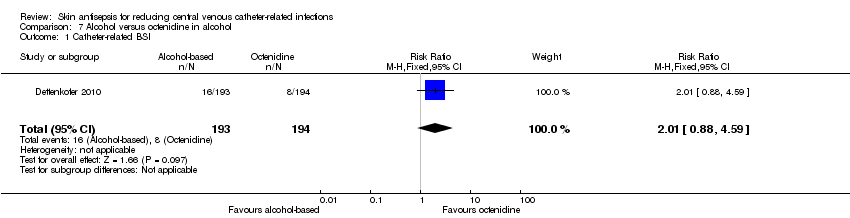

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 1 | 387 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [0.88, 4.59] |

| Analysis 7.1  Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI. | ||||

| 2 Catheter‐related BSI per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 1 | 387 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.18 [0.54, 8.77] |

| Analysis 7.2  Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 2 Catheter‐related BSI per 1000 catheter‐days. | ||||

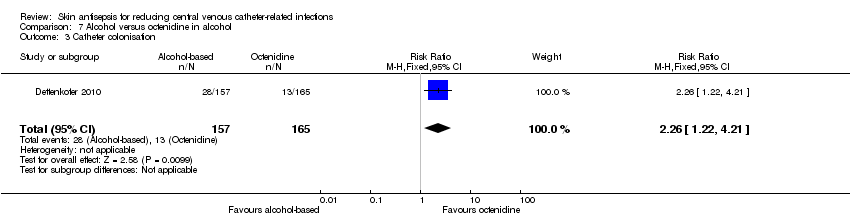

| 3 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 322 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.26 [1.22, 4.21] |

| Analysis 7.3  Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 3 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

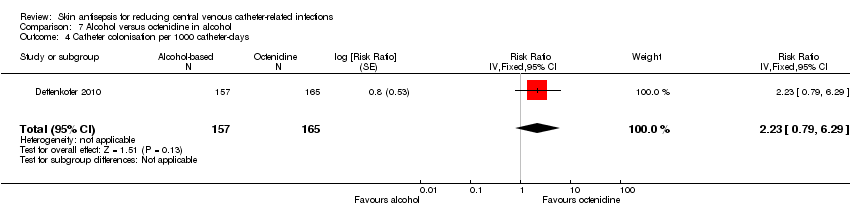

| 4 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 1 | 322 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.23 [0.79, 6.29] |

| Analysis 7.4  Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 4 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days. | ||||

| 5 Skin colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 365 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 79.00 [32.76, 125.24] |

| Analysis 7.5  Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 5 Skin colonisation. | ||||

| 6 Adverse effects Show forest plot | 1 | 398 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.60, 1.20] |

| Analysis 7.6  Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 6 Adverse effects. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

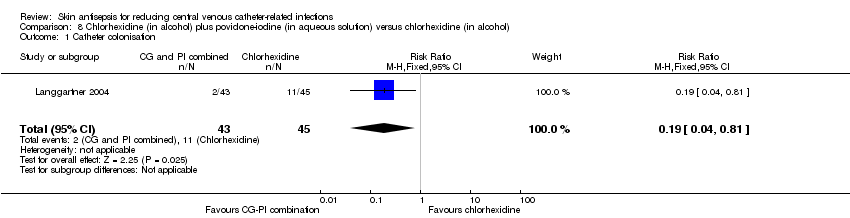

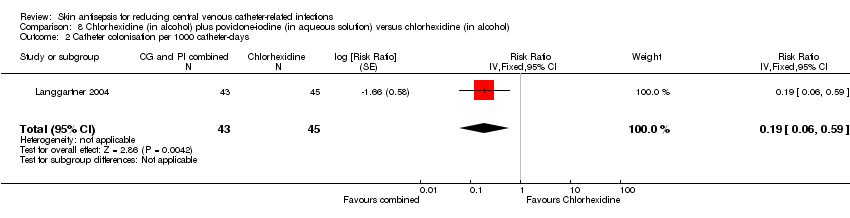

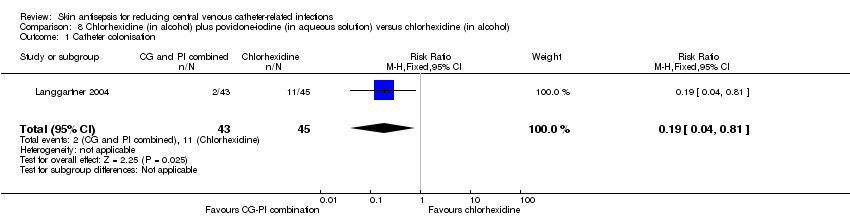

| 1 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 88 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.04, 0.81] |

| Analysis 8.1  Comparison 8 Chlorhexidine (in alcohol) plus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus chlorhexidine (in alcohol), Outcome 1 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

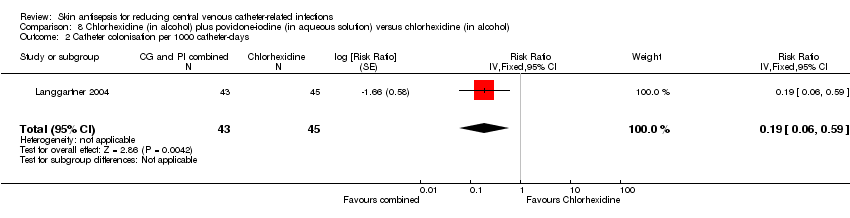

| 2 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 1 | 88 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.06, 0.59] |

| Analysis 8.2  Comparison 8 Chlorhexidine (in alcohol) plus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus chlorhexidine (in alcohol), Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 95 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.04, 0.62] |

| Analysis 9.1  Comparison 9 Chlorhexidine (in alcohol) plus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution), Outcome 1 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

| 2 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 1 | 95 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.05, 0.52] |

| Analysis 9.2  Comparison 9 Chlorhexidine (in alcohol) plus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution), Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

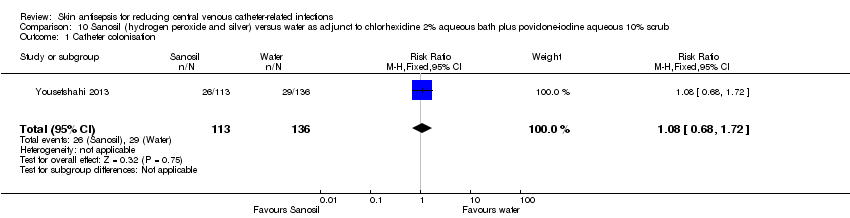

| 1 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 249 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.68, 1.72] |

| Analysis 10.1  Comparison 10 Sanosil (hydrogen peroxide and silver) versus water as adjunct to chlorhexidine 2% aqueous bath plus povidone‐iodine aqueous 10% scrub, Outcome 1 Catheter colonisation. | ||||

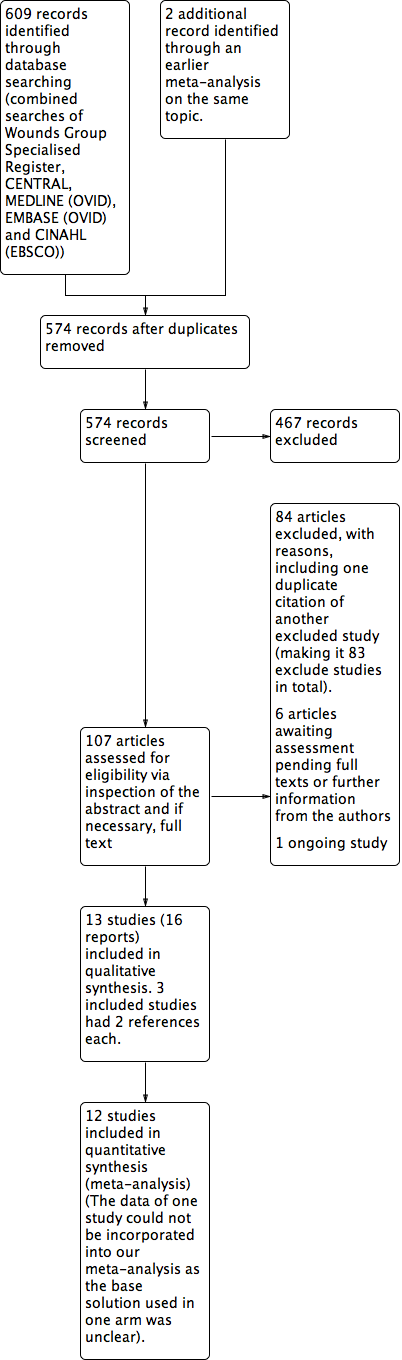

Study flow diagram.

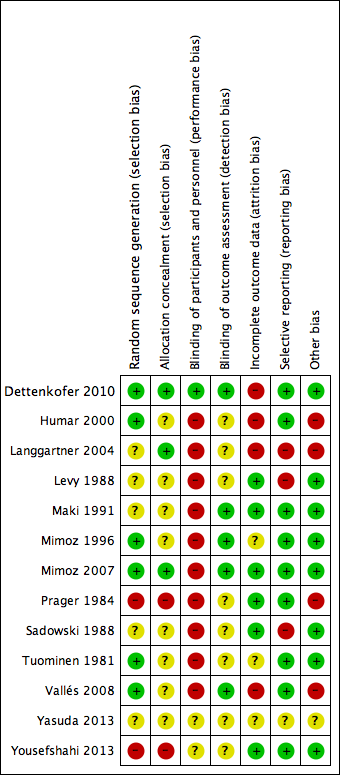

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, outcome: 1.1 Catheter‐related BSI.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, outcome: 1.3 All‐cause mortality.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, outcome: 1.4 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 1 Povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI.

Comparison 1 Povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 2 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 1 Septicaemia.

Comparison 2 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 2 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 3 Number of patients who required antibiotics during in‐dwelling period of catheter.

Comparison 3 Alcohol versus no skin antisepsis, Outcome 1 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI.

Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 2 Catheter‐related BSI per 1000 catheter‐days.

Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 3 All‐cause mortality.

Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 4 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 5 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days.

Comparison 4 Chlorhexidine versus povidone‐iodine, Outcome 6 Insertion site infection.

Comparison 5 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus alcohol, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI.

Comparison 5 Chlorhexidine (in aqueous solution) versus alcohol, Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 6 Povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus alcohol, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI.

Comparison 6 Povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus alcohol, Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related BSI.

Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 2 Catheter‐related BSI per 1000 catheter‐days.

Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 3 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 4 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days.

Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 5 Skin colonisation.

Comparison 7 Alcohol versus octenidine in alcohol, Outcome 6 Adverse effects.

Comparison 8 Chlorhexidine (in alcohol) plus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus chlorhexidine (in alcohol), Outcome 1 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 8 Chlorhexidine (in alcohol) plus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus chlorhexidine (in alcohol), Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days.

Comparison 9 Chlorhexidine (in alcohol) plus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution), Outcome 1 Catheter colonisation.

Comparison 9 Chlorhexidine (in alcohol) plus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution) versus povidone‐iodine (in aqueous solution), Outcome 2 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days.

Comparison 10 Sanosil (hydrogen peroxide and silver) versus water as adjunct to chlorhexidine 2% aqueous bath plus povidone‐iodine aqueous 10% scrub, Outcome 1 Catheter colonisation.

| Chlorhexidine compared to povidone‐iodine for patients with a central venous catheter | |||||

| Patient or population: patients with a central venous catheter | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No. of Participants | Quality of the evidence | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Povidone‐iodine | Chlorhexidine | ||||

| Catheter‐related BSI ‐ overall comparison between chlorhexidine and povidone‐iodine (during in‐patient stay) | Study population | RR 0.64 | 1436 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | |

| 64 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 | ||||

| Moderatea | |||||

| 46 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 | ||||

| Catheter‐related BSI ‐ subgroup: chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | Study population | RR 0.64 | 452 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | |

| 86 per 1000 | 55 per 1000 | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 84 per 1000 | 54 per 1000 | ||||

| Catheter‐related BSI ‐ subgroup: chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | Study population | RR 0.77 | 503 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | |

| 70 per 1000 | 54 per 1000 | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 69 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 | ||||

| Catheter‐related BSI ‐ subgroup: chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | Study population | RR 0.4 | 481 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | |

| 42 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 42 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 | ||||

| Primary BSI or clinical sepsis | No studies under this comparison assessed this outcome. | ||||

| All‐cause mortality ‐ Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | Study population | RR 1.15 | 213 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| 236 per 1000 | 271 per 1000 | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 236 per 1000 | 271 per 1000 | ||||

| All‐cause mortality ‐ Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | Study population | RR 0.8 | 222 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | |

| 236 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 236 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 | ||||

| Mortality attributable the CVC‐related infections. | No studies under this comparison assessed this outcome. | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | |||||

| a'Moderate risk' was calculated from the median control event rate for each outcome. | |||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 1 | 179 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.37, 2.61] |

| 2 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 179 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.53, 1.60] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Septicaemia Show forest plot | 1 | 136 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.91 [0.31, 27.31] |

| 2 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.61, 2.59] |

| 3 Number of patients who required antibiotics during in‐dwelling period of catheter Show forest plot | 1 | 136 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.55, 1.27] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.30, 1.85] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 4 | 1436 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.41, 0.99] |

| 1.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 2 | 452 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.32, 1.28] |

| 1.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 2 | 503 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.39, 1.53] |

| 1.3 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | 1 | 481 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.13, 1.24] |

| 2 Catheter‐related BSI per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 4 | 1450 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.30, 0.94] |

| 2.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 1 | 308 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.23, 2.93] |

| 2.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 3 | 661 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.25, 0.95] |

| 2.3 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | 1 | 481 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.06, 2.92] |

| 3 All‐cause mortality Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 1 | 213 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.72, 1.83] |

| 3.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 1 | 222 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.48, 1.34] |

| 4 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 5 | 1533 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.12, ‐0.03] |

| 4.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 2 | 452 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.09 [‐0.17, ‐0.02] |

| 4.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 3 | 600 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.11, 0.03] |

| 4.3 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | 1 | 481 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.17, ‐0.04] |

| 5 Catheter colonisation per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 5 | 1547 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.50, 0.81] |

| 5.1 Chlorhexidine in aqueous solution versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 1 | 308 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.40, 1.20] |

| 5.2 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution | 4 | 758 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.48, 0.85] |

| 5.3 Chlorhexidine in alcohol versus povidone‐iodine in alcohol | 1 | 481 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.24, 1.17] |

| 6 Insertion site infection Show forest plot | 1 | 242 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.80 [‐9.10, 3.50] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.02, 2.54] |

| 2 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.11, 1.33] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 1 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.21, 5.08] |

| 2 Catheter colonisation Show forest plot | 2 | 169 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [0.76, 4.09] |

| 2.1 Povidone‐iodine in aqueous solution versus alcohol | 1 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.49, 3.14] |

| 2.2 Povidone‐iodine‐impregnated adherent film versus alcohol | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.0 [0.51, 160.17] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter‐related BSI Show forest plot | 1 | 387 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [0.88, 4.59] |

| 2 Catheter‐related BSI per 1000 catheter‐days Show forest plot | 1 | 387 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.18 [0.54, 8.77] |