Fármacos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos tópicos para la analgesia de las abrasiones corneales traumáticas

Resumen

Antecedentes

Las abrasiones corneales traumáticas son relativamente comunes y hay una falta de consenso acerca de la analgesia en su tratamiento. Por lo tanto, es importante documentar la eficacia clínica y el perfil de seguridad de los fármacos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos (AINE) oftálmicos tópicos en el tratamiento de las abrasiones corneales traumáticas.

Objetivos

Identificar y evaluar todos los ensayos controlados aleatorios (ECA) que comparan la administración de AINE tópicos con placebo o cualquier intervención analgésica alternativa en adultos con abrasiones corneales traumáticas (incluidas las abrasiones corneales que surgen de la extracción de cuerpos extraños), para aliviar el dolor, y sus efectos sobre el tiempo de cicatrización.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se realizaron búsquedas en el Registro Cochrane Central de Ensayos Controlados (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; CENTRAL) (que contiene el Registro de Ensayos de Cochrane Ojos y Visión) (2017, número 2), MEDLINE Ovid (de 1946 hasta el 30 de marzo de 2017), Embase Ovid (de 1947 al 30 de marzo de 2017), LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database) (de 1982 al 30 de marzo de 2017), OpenGrey (Sistema de información sobre literatura gris en Europa) (www.opengrey.eu/); buscado el 30 de marzo de 2017, ZETOC (de 1993 al 30 de marzo de 2017), el registro ISRCTN (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch); buscado el 30 de marzo de 2017, ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov); buscado el 30 de marzo de 2017 y en la WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en); buscado el 30 de marzo de 2017. No se utilizaron restricciones de fecha ni de idioma en las búsquedas electrónicas de ensayos. Se comprobaron las listas de referencias de los ensayos identificados para buscar estudios potencialmente relevantes adicionales.

Criterios de selección

ECA que comparaban los AINE tópicos con placebo o cualquier intervención analgésica alternativa en adultos con abrasiones corneales traumáticas.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Dos autores de la revisión, de forma independiente, extrajeron los datos y evaluaron el riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos. La confiabilidad de las pruebas se evaluó mediante GRADE.

Resultados principales

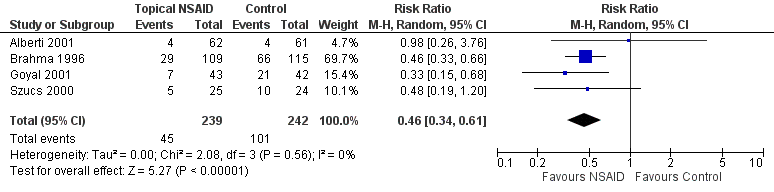

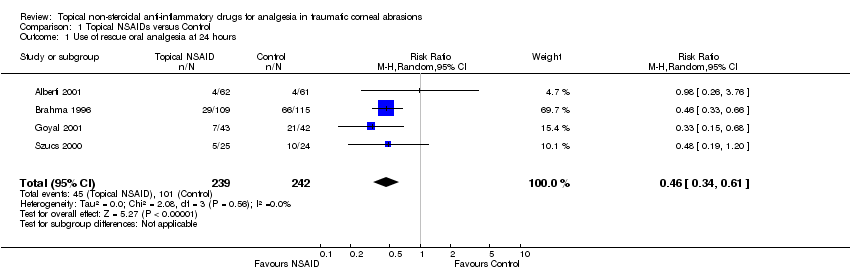

Se incluyeron nueve estudios que reunieron los criterios de inclusión y que informaban datos sobre 637 participantes. Los estudios tuvieron lugar en el Reino Unido, EE.UU., Israel, Italia, Francia y Portugal. Estos estudios compararon cinco tipos de AINE tópicos (indometacina al 0,1%, flurbiprofeno al 0,03%, ketorolaco al 0,5%, indometacina al 1%, diclofenaco al 0,1%) con el control (que constó de atención estándar y en cuatro estudios de gotas para ojos de placebo). En términos generales, los estudios estuvieron en riesgo poco claro o alto de sesgo (en particular sesgo de selección y de informe). Ninguno de los estudios incluidos informó las medidas de resultado primarias de esta revisión, a saber, la reducción de la intensidad del dolor informada por el participante de un 30% o más o de un 50% o más a las 24 horas. Cuatro ensayos, que incluían datos sobre 481 participantes que recibieron AINE o control (placebo/atención estándar), informaron la administración de analgesia de “rescate” a las 24 horas como una medida aproximada del control del dolor. Los AINE tópicos se asociaron con una reducción de la necesidad de analgesia oral en comparación con el control (cociente de riesgos [CR] 0,46; intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 0,34 a 0,61; pruebas de baja confiabilidad). Aproximadamente cuatro de cada diez pacientes del grupo de control usaron analgesia de rescate a las 24 horas. No hubo datos disponibles sobre la administración de analgesia a las 48 ni a las 72 horas.

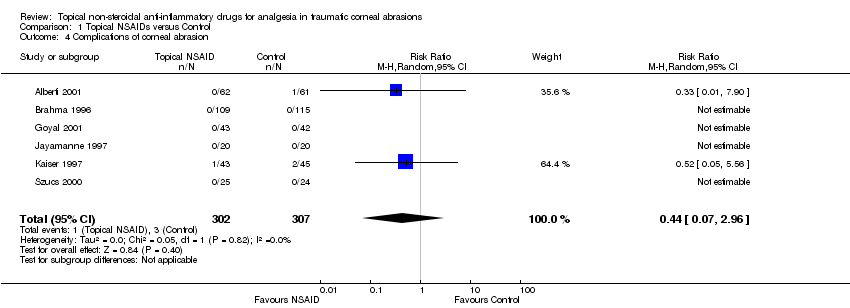

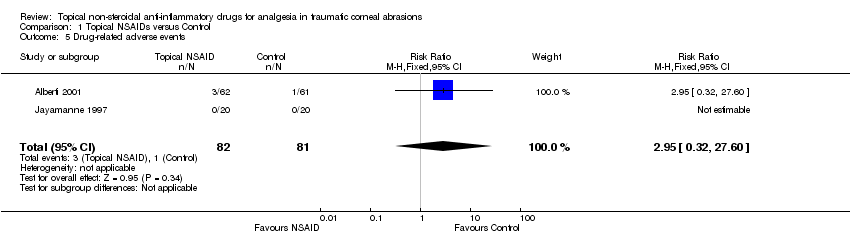

Un ensayo (28 participantes) informó la proporción de abrasiones cicatrizadas después de 24 y 48 horas. Estos resultados fueron similares en ambos brazos del ensayo. (a las 24 horas CR 1,00 [0,81 a 1,23]; a las 48 horas CR 1,00 [0,88 a 1,14]; pruebas de baja confiabilidad). En el grupo de control nueve de cada 10 abrasiones fueron cicatrizadas en un plazo de 24 horas y todas cicatrizaron a las 48 horas. Las complicaciones de las abrasiones corneales se informaron en seis estudios (609 participantes) y se informaron con poca frecuencia (4 complicaciones, 1 en los grupos de AINE [erosión corneal recurrente] y 3 en los grupos de control [2 erosiones corneales recurrentes y 1 absceso corneal], evidencia de muy baja certidumbre). Los posibles eventos adversos (EA) relacionados con los fármacos se informaron en dos ensayos (163 participantes) y el número de eventos adversos fue bajo (4 EA, 3 en el grupo de AINE, incluido el malestar/fotofobia al momento de la instilación, hiperemia conjuntival y urticaria y 1 en el grupo de control, absceso corneal) evidencia de certidumbre baja.

Conclusiones de los autores

Los hallazgos de los estudios incluidos no aportan pruebas sólidas para apoyar la administración de AINE tópicos en las abrasiones corneales traumáticas. Este hecho es importante debido a que los AINE se asocian con un costo mayor en comparación con los analgésicos orales. Ninguno de los ensayos consideró la medida de resultado primaria de la reducción de la intensidad del dolor informada por el participante de un 30% o más ni de un 50% o más a las 24 horas.

PICO

Resumen en términos sencillos

Fármacos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos (AINE) tópicos para el tratamiento del dolor en las abrasiones corneales traumáticas

¿Cuál es el objetivo de esta revisión?

El objetivo de esta revisión Cochrane era determinar si los fármacos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos (AINE) tópicos (aplicados directamente en la superficie del ojo) para las abrasiones corneales traumáticas alivian el dolor. Los investigadores Cochrane recopilaron y analizaron todos los estudios relevantes para responder esta pregunta. Se encontraron nueve estudios.

Mensajes clave

No está claro si la administración de AINE tópicos es útil en las abrasiones corneales traumáticas. El costo de los AINE tópicos es mayor que el de los tratamientos alternativos como los comprimidos orales para calmar el dolor.

¿Qué se estudió en la revisión?

Una abrasión corneal es un rasguño en la córnea del ojo. La córnea es la ventana clara que está delante del iris, que es la parte coloreada del ojo. La córnea es importante tanto para la visión como para proteger el ojo. Cuando ocurre una abrasión corneal, causa dolor y malestar significativos. Una abrasión corneal traumática es una abrasión corneal causada por una lesión, como al hurgarse el ojo o una sensación similar a tener tierra o arena atrapada bajo el párpado que raspa la córnea.

Los AINE son una forma de tratamiento del dolor para los pacientes con abrasiones corneales. Pueden aliviar el dolor.

¿Cuáles son los principales resultados de la revisión?

Los investigadores de Cochrane encontraron nueve estudios relevantes. Se encontraron tres estudios del Reino Unido, tres de los EE.UU. y tres de Italia, uno de Israel y uno de Francia/Portugal. Estos estudios usaron cinco tipos de AINE tópicos (indometacina al 0,1%, flurbiprofeno al 0,03%, ketorolaco al 0,5%, indometacina al 1%, diclofenaco al 0,1%). Los estudios compararon los AINE tópicos con gotas de antibióticos para ojos, lágrimas artificiales, parches en los ojos y gotas para ojos simuladas (placebo). Tres de los estudios fueron financiados por el fabricante mientras los otros seis estudios no informaron la fuente de financiamiento.

Los resultados de la revisión muestran que:

∙ No está claro si los pacientes tratados con AINE tópicos experimentan una reducción clínicamente significativa del dolor en comparación con los pacientes tratados con placebo o atención estándar (gotas para ojos con antibiótico, lágrimas artificiales, parches en los ojos) aunque pueden utilizar menos analgésicos orales.

∙ Cuando se informaron efectos secundarios relacionados con los fármacos y las complicaciones de la abrasión corneal (p.ej. cicatrización deficiente o infección, en dos ensayos), los números fueron bajos.

¿Cuál es el grado de actualización de esta revisión?

Los investigadores Cochrane buscaron estudios que se habían publicado hasta marzo de 2017.

Authors' conclusions

Summary of findings

| Topical NSAIDs compared to control for analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions | ||||||

| Patient or population: analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with Placebo/usual care | Risk with Topical NSAIDs | |||||

| Participant‐reported pain intensity reduction of 30%/50% or greater at 24 hours | See comment | See comment | N/A | N/A | N/A | None of the included studies reported the primary outcome measures for this review |

| Use of rescue oral analgesia at 24 hours | 400 per 1,000 | 184 per 1,000 | RR 0.46 | 481 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| Use of rescue oral analgesia at 48/72 hours | See comment | See comment | N/A | N/A | N/A | None of the included studies reported rescue analgesia at 48 hours or at 72 hours as an outcome measure |

| Proportion of abrasions healed after 24 hours | 900 per 1,000 | 900 per 1,000 | RR 1.00 | 28 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| Proportion of abrasions healed after 48 hours | 1,000 per 1,000 | 1000 per 1,000 | RR 1.00 | 28 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| Complications of corneal abrasion | 10 per 1,000 | 4 per 1,000 | RR 0.44 | 609 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| Drug‐related adverse events | 10 per 1,000 | 30 per 1,000 | RR 2.95 | 163 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Downgraded two levels for limitations in study design and implementation 2Downgraded one level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals that cross the null effect) | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

A corneal abrasion results from a disruption in the integrity of the corneal epithelium and generally results from physical external forces scraping the corneal surface (Wilson 2004). Traumatic corneal abrasions are very common ophthalmic injuries and represent a significant healthcare burden to general emergency departments (EDs), ophthalmology emergency departments and General Practitioners (Chiapella 1985; Edwards 1987; Fenton 2001; Shields 1991). In one study, ophthalmic emergencies accounted for 6.1% of all ED attendances at a district general hospital over a 12‐month period; 65% of these were trauma‐related, of which 24% were corneal abrasions (Edwards 1987). Traumatic corneal abrasions also represent a significant economic burden on society in general. For example, in the USA, corneal abrasions account for approximately 15% of all work‐related eye diseases that cause missed time from work (Harris 2008).

A traumatic corneal abrasion is also associated with significant patient morbidity. Its diagnosis is suggested by a history of recent ocular trauma (usually unilateral) and subsequent acute pain, tearing, photophobia, foreign body sensation, with or without effects on visual acuity (blurred vision). Other symptoms include: pain with extraocular muscle movement, blepharospasm and headache. Deeper scratches can cause corneal scarring that can impair vision to the point where corneal transplantation is needed. Recurrent corneal erosion may follow corneal trauma and can produce disabling ocular symptoms and predispose the cornea to infection (Watson 2013).

Description of the intervention

Although current treatment recommendations for traumatic corneal abrasions stress the use of topical antibiotics and topical (ophthalmic) or oral analgesics (Wilson 2004), there is no universal consensus regarding corneal abrasion management (Sabri 1998). Routine use of topical anaesthetics is not recommended, due to recognised corneal complications associated with their use (Pharmakakis 2002; Yagci 2011). Most corneal abrasions heal with the use of topical antibiotics (drops or ointment) and analgesics (topical (ophthalmic) or oral). Regarding management of the pain associated with corneal abrasions, topical ophthalmic non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have demonstrable efficacy, particularly where potential opioid‐induced sedation is intolerable (Weaver 2003). However, there is also no consensus regarding management of the pain caused by traumatic corneal abrasions. A national survey of 470 members of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians revealed wide variation in pain management preferences for traumatic corneal abrasions; these included oral analgesics (82.1%), cycloplegics (65.1%) and topical NSAIDs (52.8%) (Calder 2004).

There have been scattered reports of adverse effects, including corneal melting, associated with topical NSAIDs, particularly after cataract surgery, concurrent use of topical steroids and prolonged administration (Guidera 2001; Lin 2000). A previous systematic review of the use of the topical NSAIDs for corneal abrasions failed to perform a meta‐analysis of adverse effects due to insufficient data (Calder 2005).

How the intervention might work

Topical NSAID use results in a clinically significant decrease in pain (by an average of 1.3 cms on a standard 10‐cm pain scale), a decrease in oral analgesic use and a decrease in requirement for narcotic analgesia (Weaver 2003). Topical NSAID use has been shown to be associated with earlier return to work after a traumatic corneal abrasion (Kaiser 1997).

Why it is important to do this review

The use of topical NSAIDs for the management of pain in traumatic corneal abrasions is a clinically valid topic for a Cochrane Review for many reasons. Firstly, corneal abrasions are relatively common. Secondly, they are associated with significant morbidity, healthcare costs and societal economic burden. Thirdly, there is a lack of consensus regarding analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions. Fourthly, as the use of topical ophthalmic NSAIDs is very common, it is important to document any incidence of adverse effects when used in the management of traumatic corneal abrasions. Furthermore, a Cochrane Review that is continuously updated as new evidence is published may lead to clinical practice guidelines which may improve the efficiency and quality of patient care (Edwards 1987; Fenton 2001; Thyagarajan 2006). Moreover, the last non‐Cochrane systematic review on this topic was published almost twelve years ago (Calder 2005). This Cochrane Review aims to synthesise the current best evidence, which will be continuously updated as relevant new trials are published, regarding the role of topical NSAIDs for analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions (including corneal abrasions arising from foreign body removal).

Objectives

To identify and evaluate all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the use of topical NSAIDs with placebo or any alternative analgesic interventions in adults with traumatic corneal abrasions (including corneal abrasions arising from foreign body removal) to reduce pain, and its effects on healing time.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs in all languages. A RCT was defined as a study in which participants were allocated to treatment groups on the basis of a method to generate a random sequence (for example, using random‐number tables).

We did not include studies with cross‐over designs because these are not appropriate designs for the clinical condition of interest in this review and for this research question.

Types of participants

We included adults aged 18 and over with traumatic corneal abrasion(s) (including corneal abrasions arising from foreign body removal).

Types of interventions

The target intervention was topical NSAIDs (dose as defined by study authors, either overall daily dose or number of drops per day) in adults with traumatic corneal abrasions (including corneal abrasions arising from foreign body removal), compared to the following interventions:

-

Administration of cycloplegics (e.g. cyclopentolate drops, homatropine drops).

-

Administration of oral analgesics (e.g. NSAIDs, opioids, paracetamol/acetaminophen).

-

Administration of ocular lubricants (e.g. artificial tears (hydrogels)).

-

Administration of topical antibiotics (e.g. chloramphenicol, fusidic acid, trimethoprim/polymyxin).

-

Eye patching.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Participant‐reported pain intensity reduction of 30% or more at 24 hours (dichotomous data).

-

Participant‐reported pain intensity reduction of 50% or more at 24 hours (dichotomous data).

Secondary outcomes

-

Use of 'rescue' analgesia (i.e. oral analgesia) at 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours.

-

Percentage/proportion healed after 24 and 48 hours (healing should have been ascertained using fluorescein staining or slit‐lamp examination).

-

Complications of corneal abrasion (e.g. corneal ulceration, corneal infections, recurrent corneal erosion syndrome) as defined by the study authors.

-

Whether the use of concurrent topical antibiotics (drops or ointments) with additional lubricating effects reduced pain.

Adverse effects (severe, minor)

We looked for the following adverse effects:

-

Drug‐related adverse events (e.g. corneal melting, corneal scarring, allergic conjunctivitis or keratitis secondary to ocular medications).

-

Other adverse events as defined by the study authors.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language or publication year restrictions. The date of the search was 30 March 2017.

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 2) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 30 March 2017) (Appendix 1);

-

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 30 March 2017) (Appendix 2);

-

Embase Ovid (1980 to 30 March 2017) (Appendix 3);

-

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (1982 to 30 March 2017) (Appendix 4);

-

OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) (www.opengrey.eu/; searched 30 March 2017) (Appendix 5);

-

ZETOC (1993 to 30 March 2017) (Appendix 6);

-

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch; searched 30 March 2017) (Appendix 7);

-

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 30 March 2017) (Appendix 8);

-

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 30 March 2017) (Appendix 9).

Searching other resources

We made additional efforts to identify potential RCTs relevant to the topic from the references (and references of references) cited in primary sources. We did not impose any language restriction.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (RM and OG) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of studies identified by relevance and design. We obtained full‐text versions of the articles if they appeared to meet the inclusion criteria in the initial assessment of studies. A third review author (AW) evaluated any discrepant judgements.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MB and MQ) independently extracted data using a standardised data collection form that included information on the name of the first author, year of publication, study design, study population and study setting. In addition to information pertaining to participant characteristics, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, details of the interventions compared and study outcomes, we extracted information on study methodology. This included the method of randomisation, allocation concealment, frequency and handling of withdrawals, and adherence to the intention‐to‐treat principle. We resolved disagreements through discussion and in consultation with a third review author (AW) as required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MB and MQ) independently assessed and rated the methodological quality of each trial using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias as in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We judged the quality of the studies by evaluating them for the following domains:

-

Random sequence generation.

-

Allocation concealment.

-

Masking of participants and personnel, and outcome assessment.

-

Incomplete outcome data.

-

Selective outcome reporting.

-

Funding source.

-

Other potential sources of bias.

We evaluated each study and assessed it separately for these domains. We judged each explicitly as follows:

-

Low risk of bias.

-

High risk of bias.

-

Unclear risk (lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias).

We entered the data on what was reported to have happened in the study in the 'Risk of bias' table in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 5 2014). We present summary figures of the 'risk of bias in included studies' in the review. These provides a context for discussing the reliability of the results of this review. We resolved any disagreement by referring to a third review author (AW) to reach a consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated summary estimates of treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each comparison. Our measure of treatment effect was the risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and the mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes. Currently the review only includes analysis of dichotomous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of randomisation was the eye of individual trial participants. We did not anticipate that studies would have more than one eye affected in each individual; however, if this occurred we planned to note it in the review. If studies using a paired design were eligible for inclusion (i.e. studies assigning one eye to treatment and the fellow eye to control), we planned to use the generic inverse variance method to combine the results of such studies with those of studies randomising only one eye for each participant.

Dealing with missing data

No simple solution exists for the problem of missing data. We planned to handle this problem by contacting the investigators, whenever possible, to ensure that no data were missing for their study. We also planned to make explicit the assumptions of whatever method we used to cope with missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We evaluated clinical heterogeneity (differences between studies in key characteristics of the participants, interventions or outcome measures). In the absence of clinical heterogeneity, we used the I2 statistic to describe the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2003). An I2 greater than 50% may represent substantial or considerable statistical heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). The importance we placed on the observed value of I2 depended on (i) magnitude and direction of effects, and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (P value from the Chi2 test and confidence interval for I2).

We also used visual inspection of the graphic representation of studies with their 95% CIs to assess heterogeneity. We generated tables and graphs using the analysis module included in RevMan (Review Manager 5 2014). We represent pooled risk ratios pictorially as a 'forest plots' to permit visual examination of the degree of heterogeneity between studies.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias through careful attention to quality assessment, particularly methodology. We planned to use funnel plot analysis to assess publication bias if there were more than 10 studies included in the meta‐analysis. We also planned to use the Egger test (Egger 1997) to assess funnel plot asymmetry. A thorough search for unpublished studies through grey literature searches and contact with known experts in the field also helped to reduce the risk of publication bias.

Data synthesis

The results concentrate on the objectives and comparisons specified in the protocol for our review. We pooled data using a random‐effects model, because it was likely that the effects of topical NSAIDs may vary between studies. The random‐effects model takes into account between‐study variability as well as within‐study variability. When there were three or fewer trials, we used a fixed‐effect model. We performed meta‐analyses using RevMan 5 software (Review Manager 5 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to investigate heterogeneity by performing two subgroup analyses based on intuitive reasons. Firstly, we planned to perform subgroup analysis of different types of topical NSAIDs (for example, subgroup analysis of topical diclofenac and topical ketorolac). Secondly, we planned to perform subgroup analysis of traumatic corneal abrasions with different aetiologies, based on whether the abrasions are iatrogenic (arising from foreign body removal) or non‐iatrogenic in origin.

Sensitivity analysis

Finally, we planned to perform sensitivity analyses to test how sensitive the results were to reasonable changes in the assumptions that we made and in the methods for combining the data (Lau 1998). We planned to perform sensitivity analysis for randomised versus quasi‐randomised studies and eventually good‐quality studies versus poor‐quality studies.

Summary of findings

We used the principles of the GRADE system (Lau 1998) to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with the primary outcome measure of this review (pain relief), and constructed a 'Summary of findings' (SoF) table using the GRADE software (GRADEpro 2014). The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The quality of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), the directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

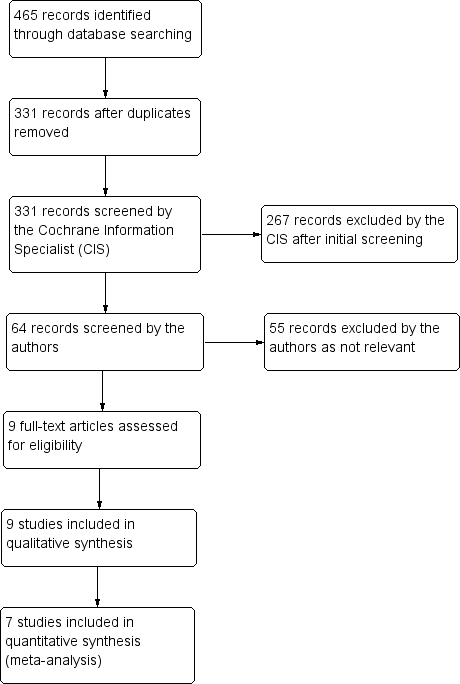

The electronic searches yielded 465 references (Figure 1). After 134 duplicate were removed the Cochrane Information Specialist (CIS) screened the remaining 331 records and removed 267 references which were not relevant to the scope of the review. We screened the remaining 64 references and obtained the full‐text reports of nine references for further assessment. We assessed the nine full‐text versions of the abstracts and all met the a priori criteria for inclusion in the final analysis. See Characteristics of included studies for details. We did not identify any ongoing studies from our searches of the clinical trials registries.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included nine studies in this review (Alberti 2001; Brahma 1996; Donnenfeld 1995; Goyal 2001; Jayamanne 1997; Kaiser 1997; Patrone 1999; Solomon 2000; Szucs 2000). The interventions compared in this review were diverse (Table 1).

| Study | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Comparator 1 | Comparator 2 |

| Topical NSAID (indomethacin 0.1%) + topical antibiotic | None | Topical antibiotic | None | |

| Topical NSAID (flurbiprofen 0.03%) + topical antibiotic | Topical NSAID + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | Placebo + topical antibiotic | Cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | |

| Topical NSAID (ketorolac 0.5%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic + bandage CL | None | Cycloplegic + topical antibiotic + bandage CL | Cycloplegic + topical antibiotic + pressure patch | |

| Topical NSAID (ketorolac 0.5%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | Placebo + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | |

| Topical NSAID (diclofenac 0.1%) + topical antibiotic | None | Placebo + topical antibiotic | None | |

| Topical NSAID (ketorolac 0,1%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | Placebo + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | |

| Topical NSAID (indomethacin 0.1%) + topical antibiotic + bandage CL | None | Topical antibiotic + bandage CL | None | |

| Topical NSAID indomethacin 1%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | Cycloplegic + topical antibiotic + pressure patch | None | |

| Topical NSAID (diclofenac 0.1%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | Placebo+ cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None |

CL: contact lens

NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

Excluded studies

We did not exclude any study after obtaining the full text of the report.

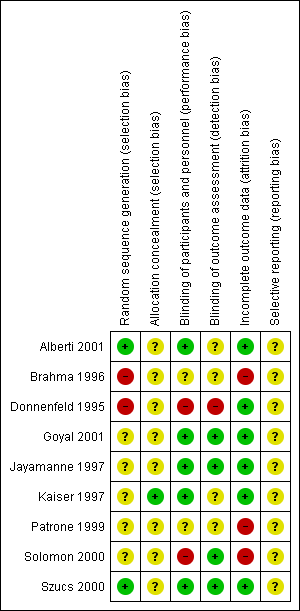

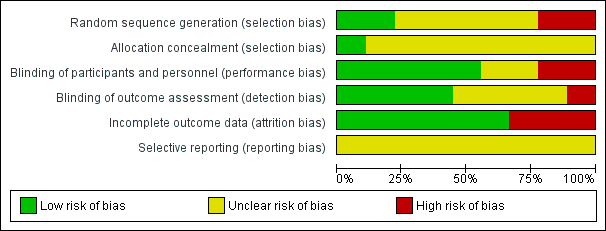

Risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated the overall quality of each study according to the methodology detailed in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies. The Characteristics of included studies table presents different 'Risk of bias' domains. Figure 2 and Figure 3 present a graph and summary of the risk of bias of included studies.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Two of the studies (Brahma 1996; Donnenfeld 1995) were at a high risk of bias due to an inadequate method of sequence generation. We rated five of the studies at an unclear risk, since there was no explicit statement about the method for sequence generation.

Allocation concealment

Eight of the studies had an unclear risk of bias because there was no explicit statement about allocation concealment.

Blinding

Performance bias

In one study, the nature of the interventions was such that double‐masking was not feasible (Solomon 2000). In two of the included studies, there was no explicit statement about masking of participants or study personnel (Brahma 1996; Patrone 1999).

Detection bias

There was a high risk of detection bias in one of the studies (Donnenfeld 1995). In four of the included studies there was a low risk of bias (Goyal 2001; Jayamanne 1997;Solomon 2000; Szucs 2000). The risk of detection bias was unclear in four studies because no explicit statement about masking of outcome assessors was reported (Alberti 2001; Brahma 1996; Kaiser 1997; Patrone 1999).

Incomplete outcome data

Three of the included studies had a high risk of attrition bias (Brahma 1996; Patrone 1999; Solomon 2000).

Selective reporting

We judged all studies to have an unclear risk, since no protocol or trial registry entry was available and it was therefore not possible to assess this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other potential sources of bias.

Given the relatively small number of included trials, we were unable to assess publication bias (Higgins 2011).

Effects of interventions

Primary outcome measures

None of the included studies reported the primary outcome measures of this review (participant‐reported pain intensity reduction of 30% or more at 24 hours and participant‐reported pain intensity reduction of 50% or more at 24 hours).

Secondary outcome measures

Use of 'rescue' analgesia (that is, oral analgesia) at 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours

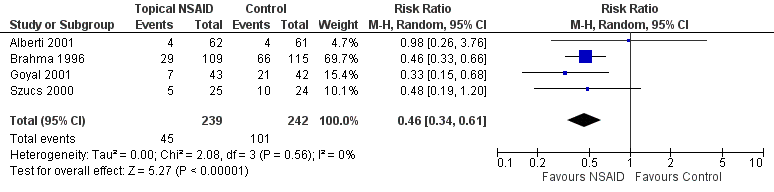

Four studies reported 'rescue' analgesia at 24 hours as an outcome measure (Alberti 2001; Brahma 1996; Goyal 2001;Szucs 2000) (participants reported = 481). Although these studies employed different comparators (Table 1), we pooled the data, since the treatment effect was in the same direction and the results were consistent. Participants taking NSAIDs were less likely to require rescue analgesia (low‐certainty evidence); (risk ratio (RR) 0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.34 to 0.61; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4).

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Topical NSAIDs versus placebo/standard care, outcome: 1.1 Use of rescue oral analgesia at 24 hours.

None of the included studies reported 'rescue' analgesia at 48 hours or at 72 hours as an outcome measure.

Percentage/proportion healed after 24 and 48 hours (healing should have been ascertained using fluorescein staining or slit‐lamp examination)

One study reported the proportion of corneal abrasions that were healed after 24 and 48 hours (Solomon 2000) (participants reported = 28). Ninety‐three per cent of abrasions were healed within 24 hours and the remainder within 48 hours. There was no difference in the proportion of abrasions healed between groups (low‐certainty evidence); 24 hours (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.23); 48 hours (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.14; Analysis 1.2 and Analysis 1.3).

Complications of corneal abrasion (as defined by the study authors)

Six of the studies reported complications of corneal abrasion as an outcome measure (Alberti 2001; Brahma 1996; Goyal 2001; Jayamanne 1997; Kaiser 1997; Szucs 2000) (participants reported = 609). Four of these studies (Brahma 1996; Goyal 2001; Jayamanne 1997; Szucs 2000) reported no complications in either study arm. One study (Alberti 2001) reported a corneal abscess in the comparator group and one study (Kaiser 1997) reported that three participants returned with a recurrent corneal erosion (two in the control group and one in the NSAID group) (very low‐certainty evidence); (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.07 to 2.96; Analysis 1.4).

Whether the use of concurrent topical antibiotics with additional lubricating effects reduced pain

None of the studies reported whether use of concurrent topical antibiotics (drops or ointments) with additional lubricating effects reduced pain.

Drug‐related adverse events

Two studies reported on drug‐related adverse events as an outcome measure (Alberti 2001; Jayamanne 1997) (participants reported = 163). Jayamanne 1997 reported no drug‐related events, while Alberti 2001 reported four events (three in the NSAID group, including discomfort/photophobia on instillation, conjunctival hyperaemia and urticaria and one in the control group, corneal abscess) very low‐certainty evidence; (RR 2.95 95% CI 0.32 to 27.60; Analysis 1.5).

Other adverse events (as defined by the study authors)

None of the nine included studies reported other adverse events as an outcome measure.

Discussion

Summary of main results

None of the included studies reported the primary outcome measures of this review, namely participant‐reported pain intensity reduction of 30% or more or of 50% or more at 24 hours. A 30% reduction in pain intensity represents a clinically important difference in pain severity that corresponds to patients' perception of adequate pain control (Lee 2003; Younger 2009).

Four trials that randomised 664 participants (481 reported) to receive NSAIDs or placebo/standard care reported on the use of ‘rescue’ analgesia at 24 hours as a proxy measure of pain control. These trials were associated with a reduction in the need for oral analgesia (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.61).

One trial, in which 28 participants were randomised, reported on the proportion of abrasions healed after 24 and 48 hours. These levels were similar between both arms of the trial.

Two trials (163 participants randomised) reported on drug‐related adverse events, with rates low and similar between the intervention and control groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The review has revealed a lack of high‐quality evidence to support the use of topical NSAIDs in traumatic corneal abrasion.

Quality of the evidence

Despite seven of the nine included studies being conducted following the publication of the CONSORT statement in 1996, the trials were generally poorly reported. Allocation concealment was unclear and in the absence of a protocol or trial registration it was not possible to assess reporting bias. Several of the trials were associated with missing outcome data that were sufficient to have a clinically relevant impact on the effect estimate.

Potential biases in the review process

As far as we are aware, we have minimised potential biases in the review process. We followed all methods set out in the published protocol and all potentially eligible studies were included. Assessment or risk of bias was limited by poor reporting and the absence of published protocols or trial registration.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A previous systematic review of topical NSAIDs for corneal abrasions (Calder 2005) included 11 RCTs, of which three were included in a meta‐analysis of self‐reported pain scores at 24 hours. NSAIDs were found to reduce self‐reported pain (weighted mean difference (WMD) ‐1.3 (95% CI ‐1.03 to 1.56)). The authors of this review concluded that topical NSAIDs can provide effective analgesia for people with traumatic corneal abrasions.

Study flow diagram.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Topical NSAIDs versus placebo/standard care, outcome: 1.1 Use of rescue oral analgesia at 24 hours.

Comparison 1 Topical NSAIDs versus Control, Outcome 1 Use of rescue oral analgesia at 24 hours.

Comparison 1 Topical NSAIDs versus Control, Outcome 2 Proportion of abrasions healed after 24 hours.

Comparison 1 Topical NSAIDs versus Control, Outcome 3 Proportion of abrasions healed after 48 hours.

Comparison 1 Topical NSAIDs versus Control, Outcome 4 Complications of corneal abrasion.

Comparison 1 Topical NSAIDs versus Control, Outcome 5 Drug‐related adverse events.

| Topical NSAIDs compared to control for analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions | ||||||

| Patient or population: analgesia in traumatic corneal abrasions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with Placebo/usual care | Risk with Topical NSAIDs | |||||

| Participant‐reported pain intensity reduction of 30%/50% or greater at 24 hours | See comment | See comment | N/A | N/A | N/A | None of the included studies reported the primary outcome measures for this review |

| Use of rescue oral analgesia at 24 hours | 400 per 1,000 | 184 per 1,000 | RR 0.46 | 481 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| Use of rescue oral analgesia at 48/72 hours | See comment | See comment | N/A | N/A | N/A | None of the included studies reported rescue analgesia at 48 hours or at 72 hours as an outcome measure |

| Proportion of abrasions healed after 24 hours | 900 per 1,000 | 900 per 1,000 | RR 1.00 | 28 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| Proportion of abrasions healed after 48 hours | 1,000 per 1,000 | 1000 per 1,000 | RR 1.00 | 28 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| Complications of corneal abrasion | 10 per 1,000 | 4 per 1,000 | RR 0.44 | 609 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| Drug‐related adverse events | 10 per 1,000 | 30 per 1,000 | RR 2.95 | 163 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | ‐ |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Downgraded two levels for limitations in study design and implementation 2Downgraded one level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals that cross the null effect) | ||||||

| Study | Intervention 1 | Intervention 2 | Comparator 1 | Comparator 2 |

| Topical NSAID (indomethacin 0.1%) + topical antibiotic | None | Topical antibiotic | None | |

| Topical NSAID (flurbiprofen 0.03%) + topical antibiotic | Topical NSAID + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | Placebo + topical antibiotic | Cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | |

| Topical NSAID (ketorolac 0.5%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic + bandage CL | None | Cycloplegic + topical antibiotic + bandage CL | Cycloplegic + topical antibiotic + pressure patch | |

| Topical NSAID (ketorolac 0.5%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | Placebo + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | |

| Topical NSAID (diclofenac 0.1%) + topical antibiotic | None | Placebo + topical antibiotic | None | |

| Topical NSAID (ketorolac 0,1%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | Placebo + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | |

| Topical NSAID (indomethacin 0.1%) + topical antibiotic + bandage CL | None | Topical antibiotic + bandage CL | None | |

| Topical NSAID indomethacin 1%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | Cycloplegic + topical antibiotic + pressure patch | None | |

| Topical NSAID (diclofenac 0.1%) + cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | Placebo+ cycloplegic + topical antibiotic | None | |

| CL: contact lens | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Use of rescue oral analgesia at 24 hours Show forest plot | 4 | 481 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.34, 0.61] |

| 2 Proportion of abrasions healed after 24 hours Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Proportion of abrasions healed after 48 hours Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Complications of corneal abrasion Show forest plot | 6 | 609 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.07, 2.96] |

| 5 Drug‐related adverse events Show forest plot | 2 | 163 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.95 [0.32, 27.60] |