Gouttes oculaires de N‐acetylcarnosine (NAC) pour la cataracte liée à l'âge

Résumé scientifique

Contexte

La cataracte est la principale cause mondiale de cécité. Le seul traitement disponible pour la cataracte est la chirurgie. La chirurgie nécessite des personnes hautement qualifiées et des installations coûteuses. Lorsque celles‐ci ne sont pas disponibles, les patients ne reçoivent pas de traitement. Une forme de traitement qui ne nécessiterait pas de chirurgie serait une alternative utile pour les personnes atteintes de cataracte symptomatique qui ne peuvent ou ne veulent pas recourir à la chirurgie. Si un collyre existait pouvant inverser ou même empêcher la progression de la cataracte, alors cela serait une option de traitement supplémentaire utile.

La cataracte tend à résulter du stress oxydatif. La protéine L‐carnosine, est connue pour avoir un effet antioxydant sur la cataracte ; aussi sur le plan biochimique, il existe une logique forte pour explorer la L‐carnosine comme agent pour inverser ou même empêcher la progression de la cataracte. Administrée en collyre, la L‐carnosine ne peut pas pénétrer dans l'œil. Cependant, appliquée à la surface de l'œil, la N‐acetylcarnosine (NAC) pénètre par la cornée dans la chambre antérieure de l'œil (près de l'endroit où se trouve la cataracte), où elle est métabolisée en L‐carnosine. Par conséquent, il est possible que l'utilisation de collyres NAC puisse inverser ou même empêcher la progression de la cataracte, améliorant ainsi la vision et la qualité de vie.

Objectifs

Évaluer l'efficacité des gouttes oculaires NAC pour prévenir ou retarder la progression de la cataracte.

Stratégie de recherche documentaire

Nous avons effectué des recherches dans CENTRAL (qui contient le registre d'essais du groupe Cochrane sur l'œil et la vision) (2016, numéro 6), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (de janvier 1946 à juin 2016), Embase (de janvier 1980 à juin 2016), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) (de janvier 1985 à juin 2016), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (de 1982 à juin 2016), le registre ISRCTN (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) et l'International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) de l'Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS), (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). Nous n'avons appliqué aucune restriction concernant la langue ou la date dans les recherches électroniques d'essais. Nous avons effectué les dernières recherches dans les bases de données électroniques le 28 juin 2016. Nous avons effectué une recherche manuelle dans les rencontres de l'American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) et de l'European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS) de 2005 jusqu'à septembre 2015.

Critères de sélection

Nous avions prévu d'inclure des essais contrôlés randomisés ou quasi‐randomisés dans lesquels la NAC était comparée à un témoin chez les personnes atteintes de cataracte liée à l'âge.

Recueil et analyse des données

Nous avons utilisé les procédures méthodologiques standard prévues par Cochrane.

Résultats principaux

Nous avons identifié deux études potentiellement éligibles provenant de Russie et des États‐Unis. Une étude était divisée en deux bras : le premier bras d'une durée de six mois, avec un suivi deux fois par mois ; le deuxième bras d'une durée de deux ans avec un suivi six fois par mois . L'autre étude s'étalait sur quatre mois avec une collecte de données au début et à la fin de l'étude uniquement. Un total de 114 personnes ont été recrutées dans ces études. L'âge variait de 55 à 80 ans.

Nous ne sommes pas parvenus à obtenir suffisamment d'informations pour déterminer avec fiabilité comment ces deux études ont été conçues et menées. Nous avons contacté les auteurs de ces études, mais nous n'avons pas encore reçu de réponse. Par conséquent, ces études sont considérées comme « en attente de classification » dans la revue jusqu'à ce que des informations suffisantes puissent être obtenues auprès des auteurs.

Conclusions des auteurs

Il n'existe actuellement aucune preuve convaincante que la NAC inverse ou empêche la progression de la cataracte (définie comme une modification dans l'aspect de la cataracte que ce soit en mieux ou en pire). Les études futures devraient être randomisées, en double aveugle, contrôlées par placebo et portant sur des critères de jugement de qualité de vie standardisés et des mesures de résultats validées en termes d'acuité visuelle, de sensibilité au contraste et à l'éblouissement et suffisamment de grande ampleur pour détecter les effets indésirables.

PICO

Résumé simplifié

Gouttes de N‐acetylcarnosine (NAC) pour la cataracte liée à l'âge

Quel est l'objectif de cette revue ?

L'objectif de cette revue Cochrane a été de déterminer si les gouttes oculaires de NAC peuvent prévenir ou inverser la progression de la cataracte (opacification du cristallin de l'œil).

Principaux messages

On n'est pas sûr que les gouttes oculaires de NAC préviennent ou inversent la progression de la cataracte.

Qu'est‐ce qui a été étudié dans cette revue ?

L'œil possède une lentille transparente qui concentre la lumière sur l'arrière de l'œil. Quand les personnes vieillissent cette lentille peut devenir opaque, conduisant à des problèmes de vision. On nomme cataracte ce cristallin opaque. Les médecins peuvent ôter la cataracte et la remplacer par une lentille artificielle. Ceci est généralement une opération très efficace. Mais toute opération comporte des risques et peut être vécue péniblement. Les cataractes sont courantes chez des populations âgées et la chirurgie de la cataracte est coûteuse pour les systèmes de santé. C'est pourquoi il existe un intérêt pour la prévention ou le traitement de la cataracte, de sorte que la chirurgie puisse être évitée.

Dans le cadre du métabolisme normal, notre corps produit des substances chimiques qui contiennent de l'oxygène et sont réactifs (« dérivés réactifs de l'oxygène »). Une des théories du vieillissement dit que ces substances chimiques peuvent être dangereuses et pourraient conduire à des modifications de notre corps liées à l'âge, tels que la cataracte. Ceci est connu sous le nom de stress oxydatif. La N‐acetylcarnosine (NAC) est supposée être en mesure de lutter contre certains des effets du stress oxydatif, car elle a des propriétés antioxydantes. Si la NAC peut empêcher le cristallin de s'opacifier ou en réduire l'opacité, cela pourrait améliorer la vision et la qualité de vie.

Quels sont les principaux résultats de la revue ?

Les chercheurs Cochrane ont trouvé deux études potentiellement pertinentes. Les études comparaient des collyres NAC à un placebo ou à l'absence de traitement. Ces études ont été réalisées en Russie et aux États‐Unis et ont été menées par le même groupe de recherche. Les chercheurs Cochrane n'ont pas été en mesure de trouver suffisamment d'informations sur ces études pour les inclure dans la revue. Ces études sont considérées comme « en attente de classification » dans la revue jusqu'à ce que des informations suffisantes puissent être obtenues auprès des auteurs.

Quelle est l'actualité de cette revue ?

Les auteurs de la revue ont recherché des études publiées jusqu'au 28 juin 2016. .

Authors' conclusions

Background

Description of the condition

Cataract is opacification of the lens within the eye, which can cause symptoms due to poor, or altered quality of vision. This can lead to a reduced ability to carry out activities of daily living, driving and working (Steinberg 1994).

Recent figures show that cataract is responsible for 48% of world blindness, representing some 17.6 million people making it the leading cause of blindness (Resnikoff 2004).

Description of the intervention

Currently, the only widely‐accepted treatment for cataract is removal. This is done through an operation. As the cataract is the natural lens of the eye that has reduced clarity, its removal usually precedes replacement of the natural lens with an artificial one.

There were 320,000 cataract operations carried out in the UK between 2012 and 2013 (HSCIC 2013). In the United States, the figure is estimated at 1.7 million operations carried out in Medicare beneficiaries in 2004 (Schein 2012).

Currently there is no treatment for cataracts aside from surgery. One of the causes of cataract may be oxidative stress within the lens. Oxidative stress results from the formation of free radical species. Carnosine is a naturally occurring dipeptide, implicated in reducing free radicals in the body (Dahl 1988).

Anti‐cataract drops are instilled onto the affected eye twice a day. A course of treatment is recommended for a minimum of two months and may be required indefinitely to prevent progression of the cataract.

How the intervention might work

Topical application of carnosine onto the ocular surface does not result in penetration into the eye. Hence, a vehicle has been developed, called N‐acetylcarnosine (NAC). When NAC is instilled onto the eye it penetrates the anterior chamber of the eye through the cornea. Subsequent metabolism of NAC within the eye produces L‐carnosine, the active drug (Babizhayev 1996).

L‐carnosine has been shown to have an antioxidant effect on the cataractous lens (Babizhayev 1989). Consequently, it is possible that topical administration of NAC could lead to a reduction in cataract by either slowing down the progression of the cataract or indeed reversing the cataractous change.

Why it is important to do this review

The current forms of management are either conservative (do nothing) or surgical. The cataract(s) may cause the patient to cease or downgrade certain activities such as driving, working and self‐caring.

Overall success rates for cataract surgery include 95% of patients being satisfied with the results of the surgery (Lum 2000); the quoted risk of sight‐threatening infection is 0.1% (Montan 2002).

In high‐income countries a medical treatment or prophylactic agent such as NAC eye drops would add to the treatment options available to the ophthalmologist and medical practitioners in the primary care setting; fewer people may need to consult an ophthalmologist and of those who did, fewer may require surgery. Individuals may be able to choose which treatment option they prefer and fewer surgical complications would arise from fewer operations. In countries with emerging economies, it may mean the difference between survival and death. Ultimately, more people may have improved vision and fewer may have worse vision.

It is important to identify whether the evidence supports the theory. There are multiple freely‐available brands of eye drops purported to reverse cataract. These can be obtained without prescription and over the Internet. Unless there is evidence to support their use, they should not be distributed. Conversely, manufacturers of machinery, consumables and intraocular lenses relevant to cataract surgery may not be motivated to advance research in this field or share study results due to the possible loss of income that would follow the successful use of such an eye drop. Conducting this review could eliminate this bias.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of carnosine to prevent or reverse the progression of cataract.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized and quasi‐randomised controlled trials. We excluded cross‐over trials due to the uncertainty regarding carry‐over effects.

Types of participants

We included trials where participants are over 50 years of age with measurable cataract, specifying which eye is affected (or both eyes), as defined by a suitably qualified medical practitioner or researcher, which is shown to be affecting their quality of life through reduced or abnormal vision. We did not make any demographic differentiations. We excluded participants with any ocular comorbidity, as this condition may make it difficult to diagnose the cause of reduced vision.

Types of interventions

We included all trials where topical NAC is compared to a control (such as saline or artificial tear) or to cataract surgery. Included trials had a minimum treatment period of two months at any dose and frequency.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Cataract appearance as defined on LOCS III grading slides or Scheimpflug photography (pixel counting).

We planned to assess the primary outcome as short‐term (less than one year) and long‐term (more than one year). Change was defined by the trial investigators.

Secondary outcomes

-

Quality of life as measured by validated quality of life questionnaires, namely VCM1, IVI, VFQ‐25, AVL, Van Dijk, NHI, Carta, SQDL‐DVI, ADVS, VF‐14, VDA, CSS, TyPE, HVAT, MIOLS VFQOL, Catquest, Mone‐stam and VFI.

-

Visual acuity as measured by Snellen (imperial or metric), LogMAR or ETDRS charts.

-

Contrast sensitivity as measured by validated printed optotype or grating tests, namely Mentor B‐VAT, CSV‐1000, MCT 8000, Pelli‐Robson, ETDRS, Cambridge, Regan and Joyce.

-

Glare disability as measured by validated glare disability tests, namely Mentor BAT, Miller‐Nadler and Berkely glare test.

Adverse effects

As reported.

We planned to assess all secondary outcomes as short‐term (less than one year) and long‐term (more than one year). Change was defined by the trial investigators.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) (2016, Issue 6), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to June 2016), Embase (January 1980 to June 2016), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) (January 1985 to June 2016), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to June 2016), the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 28 June 2016.

See Appendices for details of search strategies for CENTRAL (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), Embase (Appendix 3), CINAHL (Appendix 4), AMED (Appendix 5 ), ISRCTN (Appendix 6), ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 7) and the WHO ICTRP (Appendix 8) .

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of included studies and searched the Science Citation Index database to identify any additional trials. We handsearched the society meetings of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) and the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons (ESCRS) from 2005 to September 2015.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Both review authors (VD, AB) searched through the results and independently extracted data in duplicate. We included studies on the basis of the criteria specified above. For studies that we labelled as 'include' or 'unsure', we obtained a full‐text report of the study. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009), and Characteristics of excluded studies table. The two review authors resolved any disagreement by discussion.

Data extraction and management

We designed a paper data collection form. The form consisted of study and version ID, review author ID, citation and contact details, confirmation of eligibility for review, any reasons for exclusion of participants, study design, study duration, evidence of sequence generation and allocation sequence concealment, masking and documentation of any concerns over bias.

-

Participant factors: number, setting, diagnostic criteria, age, sex, country and study dates.

-

Intervention data: number of groups, number of participants per group and details of intervention for all groups.

-

Outcomes: quality of life (differences in scores between baseline and study endpoint), cataract severity (differences in LOCS III scores and density (Scheimpflug) between baseline and study endpoint) and visual function (differences in measured visual acuity and contrast sensitivity between baseline and study endpoint).

We planned to collect these data at short‐term (less than one year) and at long‐term (more than one year) intervals. We based the outcome criteria on change from the baseline; we recorded scales, including limits and units of measurement.

-

Results: any missing participants, summary data as detailed above including means, confidence intervals and P values.

-

Adverse event data: (worsening in quality of life scores, visual function, or cataract within the study period, or adverse effects from topical application of NAC drops, i.e. pain, eye infection, allergy and scarring to ocular surface) and relevant notes.

We documented sources of funding, along with key conclusions from study authors, any references to related studies and any comments from the review authors.

Both review authors independently collected all the data in duplicate. One review author (VD) entered the data from both review authors into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014), and the second review author (AB) then checked that the data had been correctly entered.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias as per Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions assessing the following (Higgins 2011): sequence generation, allocation concealment, masking (blinding) of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. We assessed all parameters as 'low', 'high' or 'unclear' risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to analyse ordinal data such as visual acuity and LOCS III grading as continuous data, using their respective standardised mean differences (SMDs).

We planned to analyse continuous data such as cataract density (measured by pixel counting on a Scheimpflug camera system) and quality of life data, with respective SMDs, as the measurement scales may vary depending upon which equipment or method(s) are used in each study.

We planned to consider data on glare sensitivity and contrast sensitivity as ordinal or continuous, depending upon the measurement method used.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only studies where people are randomized to treatment. We excluded trials where one eye receives treatment and the other placebo.

Trialists may use two main methods to deal with the problem of non‐independence of data from eyes: (i) they may enrol one eye per person into the trial, or (ii) they may analyse data from both eyes making corrections for within‐person correlation.

For (i), we documented the criteria used to define which eye is to be included in the trial.

For (ii), if the trialist has not adjusted for within‐person correlation, we planned to take statistical advice, but as no trials were included this is not relevant for this version of the review.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to document the reasons why participants were not followed up, if reported. We planned to contact study trialists for further clarification as needed. At that stage we planned to be able to make judgements as to whether the data are missing at random or not. We planned to address the potential impact of missing data in the Discussion section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to investigate clinical heterogeneity by examining differences in population, intervention and outcomes. We planned to investigate statistical heterogeneity by looking at the forest plots and statistical tests (Chi2 and the I2 statistic) since tests for statistical heterogeneity are underpowered when the number of studies is low.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots to help in our assessment of bias as per Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Sterne 2011), but as there was not enough data, we did not create funnel plots.

Data synthesis

As we cannot assume that the intervention will have the same effect in different groups of people, that is, that each included study will be measuring the same effect, we planned to pool the data using a random‐effects model (providing there are three or more included trials providing relevant data). A random‐effects model will allow for differences in the effect of the intervention between the included trials. If the heterogeneity is too great, then meta‐analysis will not be possible.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to consider the following subgroups but in the event there were not enough data to do these analyses.

-

Smokers versus non‐smokers.

-

Diabetics versus non‐diabetics.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not plan to conduct any sensitivity analysis for this review.

Summary of findings

We planned to include a 'Summary of findings' table, but due to the sparse and uncertain data we did not do this. In future updates of this review, if we identify further trials, we will include a 'Summary of findings' table including our primary and secondary outcomes.

We assessed the overall quality of the evidence using GRADEpro GDT (GRADEpro GDT 2014). This was done against the following GRADE parameters (Atkins 2004): study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias .The following outcomes were assessed: cataract appearance, quality of life, visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and glare disability.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

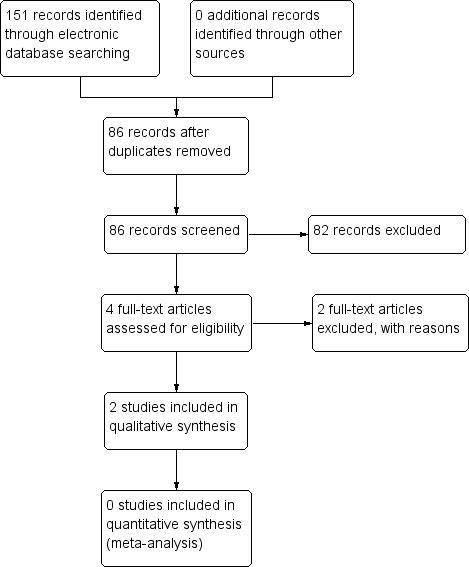

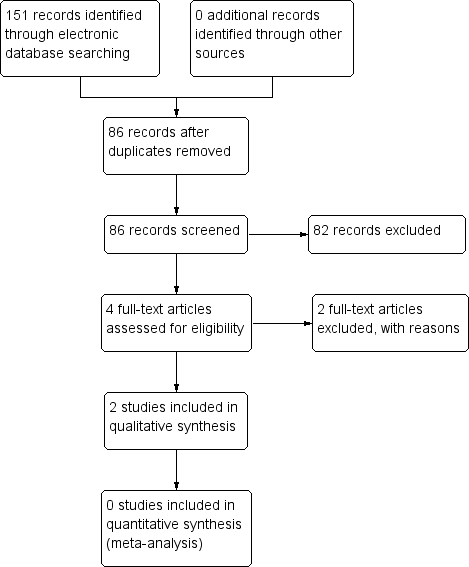

The electronic searches yielded a total of 151 references (Figure 1). The Cochrane Information Specialist removed 65 duplicate records and we screened the remaining 86 reports. We rejected 82 records after reading the abstracts and obtained the full‐text reports of four references for assessment. All four studies were conducted by Dr Babizhayev ‐ after assessing the studies, we considered Babizhayev 2002; and Babizhayev 2004 were potentially eligible and we excluded Babizhayev 2009 and Babizhayev 2011; see below for details.

Study flow diagram.

Studies awaiting classification

We identified two potentially eligible studies (Babizhayev 2002; Babizhayev 2004).

In Babizhayev 2002, 49 people (76 eyes) were enrolled in Russia and the United States. Some participants were followed up to six months and others to 24 months, however, the rationale for this was not clear, and these were described as two different studies. Participants were randomized to NAC 1% (26 people, 41 eyes) or control. Some of the control group received placebo (13 people, 21 eyes) and others received no treatment (10 people, 14 eyes), but again it was not clear why this was the case. Outcomes measured included cataract appearance (image analysis), visual acuity (Snellen), a measure of glare sensitivity and adverse effects.

In Babizhayev 2004, 65 people were enrolled in the United States. People with cataract were identified from the medical notes and the participants were randomly allocated to NAC (35 people) or placebo (30 people) and followed up for four months. Outcomes included visual acuity (logMAR) and the halometer glare disability test.

We were unable to obtain sufficient information to reliably determine how both these studies were designed and conducted. We have contacted the author of these studies, but have not yet received a reply. Therefore, these studies are assigned as ‘awaiting classification’ until sufficient information can be obtained from the authors.

Excluded studies

We excluded two studies (Babizhayev 2009; Babizhayev 2011), and reasons for exclusion can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

No studies were found that met the inclusion criteria.

Effects of interventions

No studies were found that met the inclusion criteria.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Two studies potentially met the inclusion criteria for this review but we were unable to obtain further information from the study authors to enable us to judge whether they were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There is insufficient good quality evidence to be able to answer the review question.

Potential biases in the review process

We followed procedures expected by Cochrane.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Other reviews currently focus on the biochemical and structural aspects of cataractogenesis. As far as we are aware there have been no other independent assessment of the clinical trials of NAC drops in the prevention of cataract.

Study flow diagram.