Tratamiento con células madre para la cardiopatía isquémica crónica y la insuficiencia cardíaca congestiva

Resumen

Antecedentes

El uso de células madre constituye un enfoque alentador en el tratamiento de la cardiopatía isquémica crónica y la insuficiencia cardíaca congestiva. En la última década se ha realizado un gran número de ensayos controlados aleatorios en todo el mundo que han generado resultados contradictorios.

Objetivos

La evaluación crítica de las pruebas clínicas sobre la seguridad y la eficacia de las células madre/progenitoras derivadas de la médula ósea adulta y autólogas como tratamiento para la cardiopatía isquémica crónica y la insuficiencia cardíaca congestiva.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se hicieron búsquedas de ensayos relevantes en CENTRAL en la Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, LILACS, y en cuatro bases de datos de ensayos en curso hasta el 14 diciembre 2015.

Criterios de selección

Fueron elegibles los ensayos controlados aleatorios que compararon las células madre/progenitoras derivadas de la médula ósea adulta y autólogas con ninguna célula en pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica crónica e insuficiencia cardíaca congestiva. Cointervenciones como la angioplastia primaria, la cirugía o la administración de agentes movilizadores de células madre, se incluyeron cuando se administraron por igual a los brazos de tratamiento y control.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Dos autores de la revisión examinaron de forma independiente todas las referencias según su elegibilidad, evaluaron la calidad de los ensayos y extrajeron los datos. Para realizar la evaluación cuantitativa de los datos se utilizaron metanálisis de efectos aleatorios. La heterogeneidad se evaluó mediante la estadística I2 y la heterogeneidad significativa (I2 mayor del 50%) se exploró mediante análisis de subgrupos. La calidad de las pruebas se evaluó mediante el enfoque GRADE. Se creó la tabla "Resumen de los hallazgos" mediante GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro), y se excluyeron los estudios con un riesgo alto o incierto de sesgo de selección. El resumen de los hallazgos se centró en el seguimiento a largo plazo de la mortalidad, los resultados de morbilidad y la fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo medida con imagenología de resonancia magnética.

Resultados principales

En esta actualización de la revisión se incluyeron 38 ensayos controlados aleatorios con 1907 participantes (1114 recibieron tratamiento con células, 793 controles). El riesgo de selección en 23 ensayos fue alto o incierto. Otras fuentes de sesgo potencial incluyeron la falta de cegamiento de los participantes (12 ensayos) y el patrocinio total o parcial por la industria (13 ensayos).

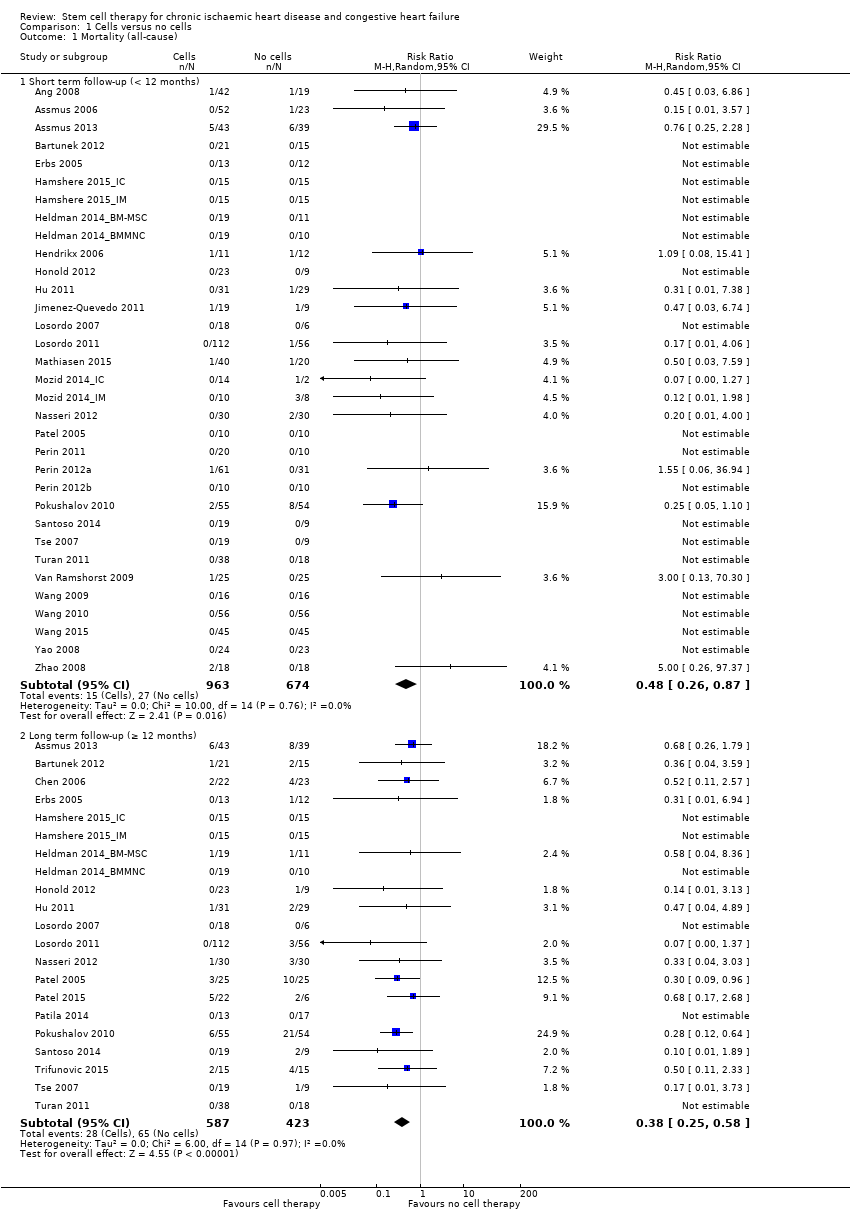

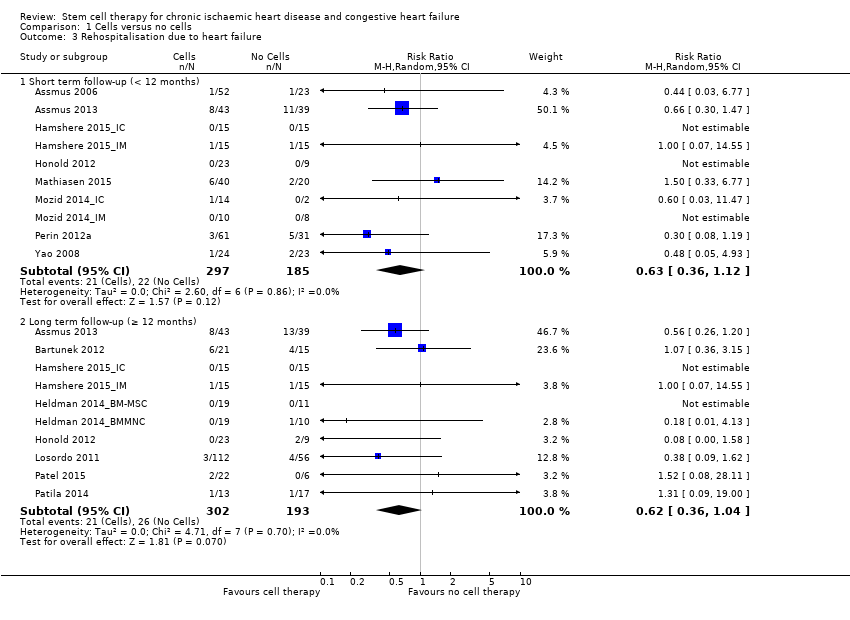

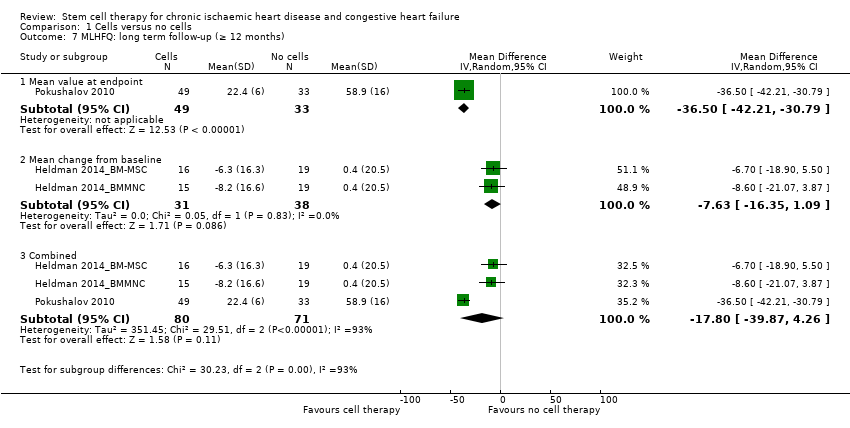

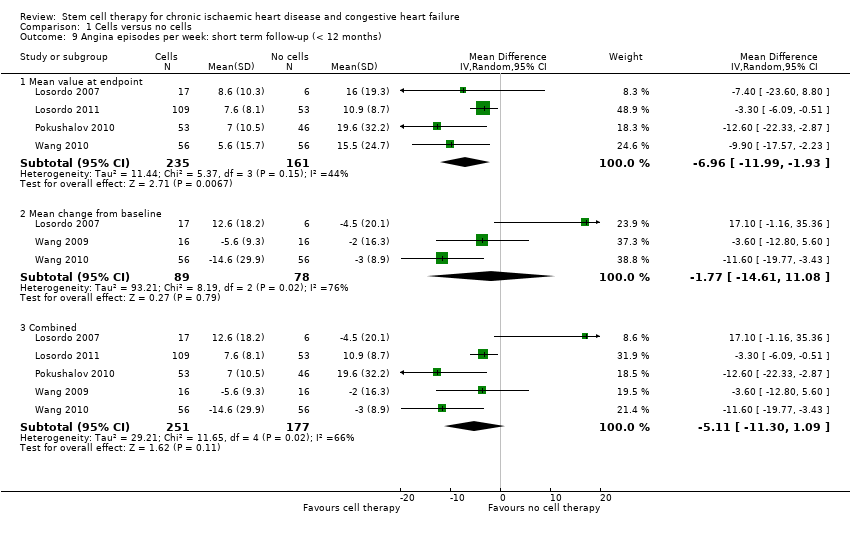

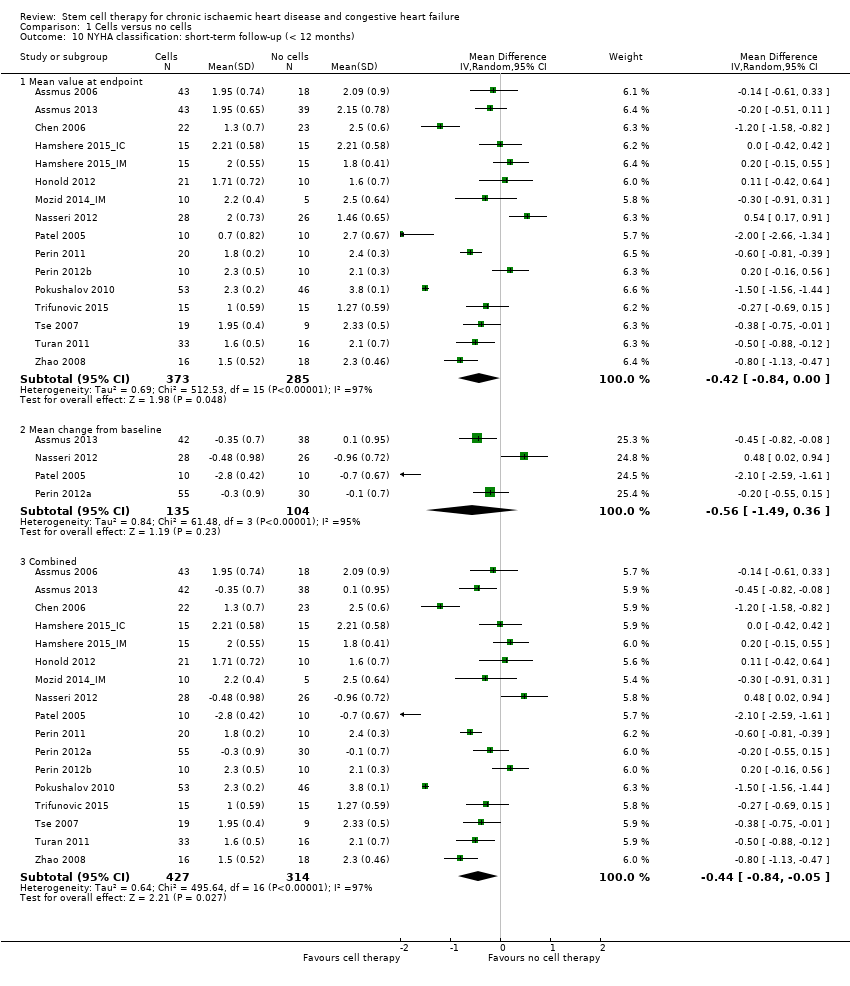

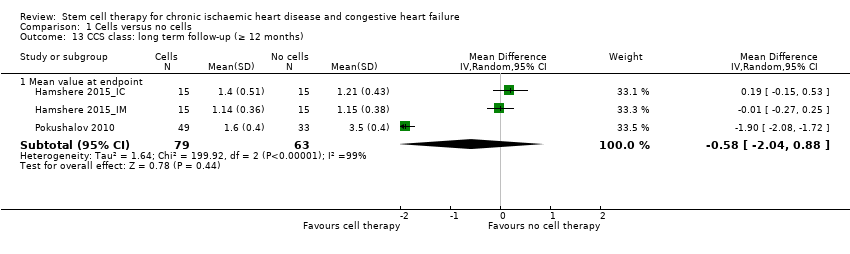

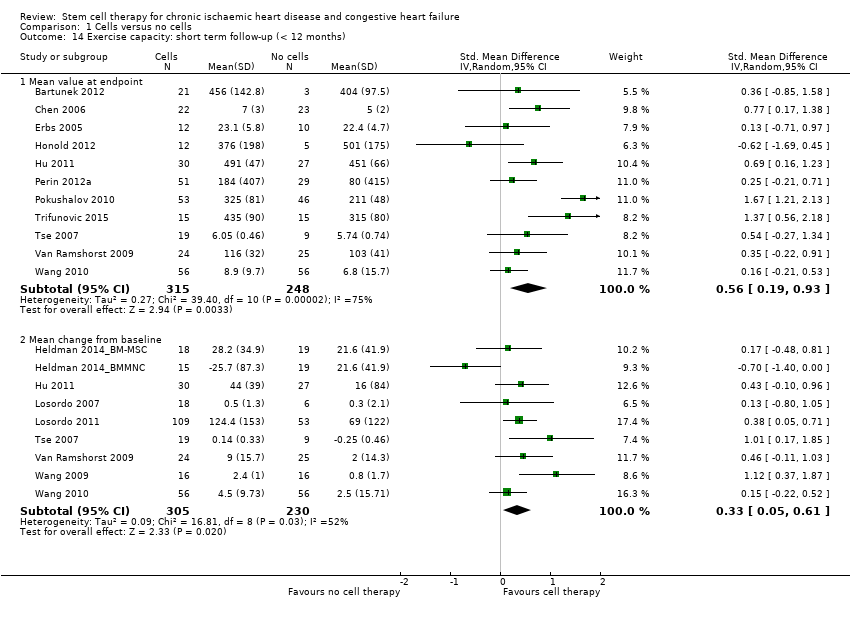

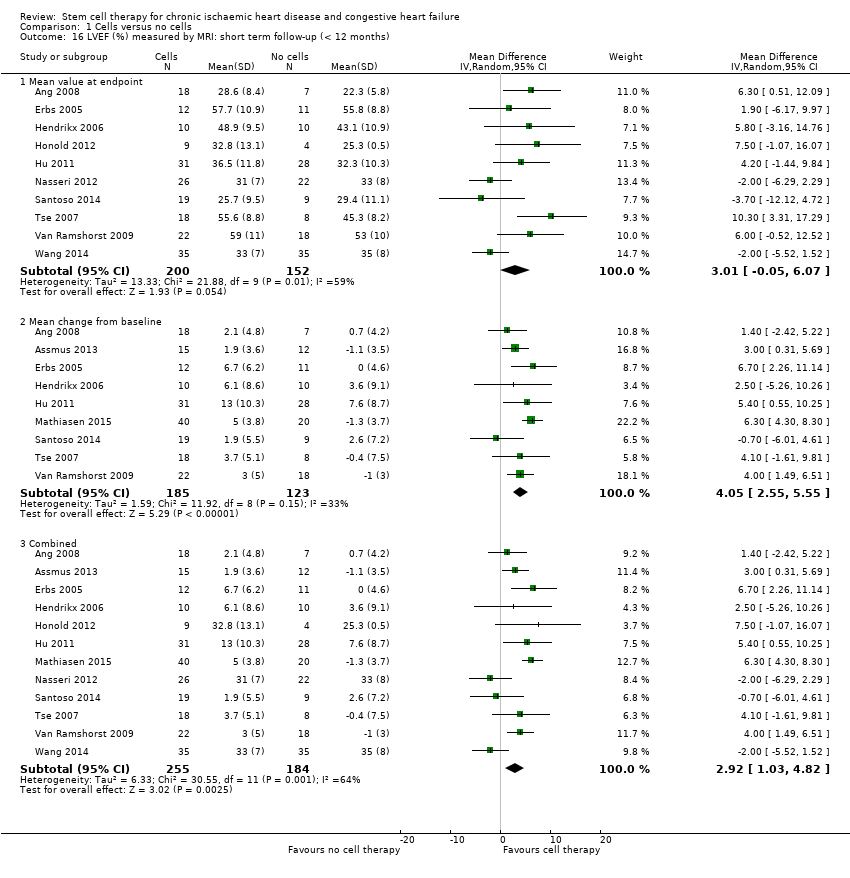

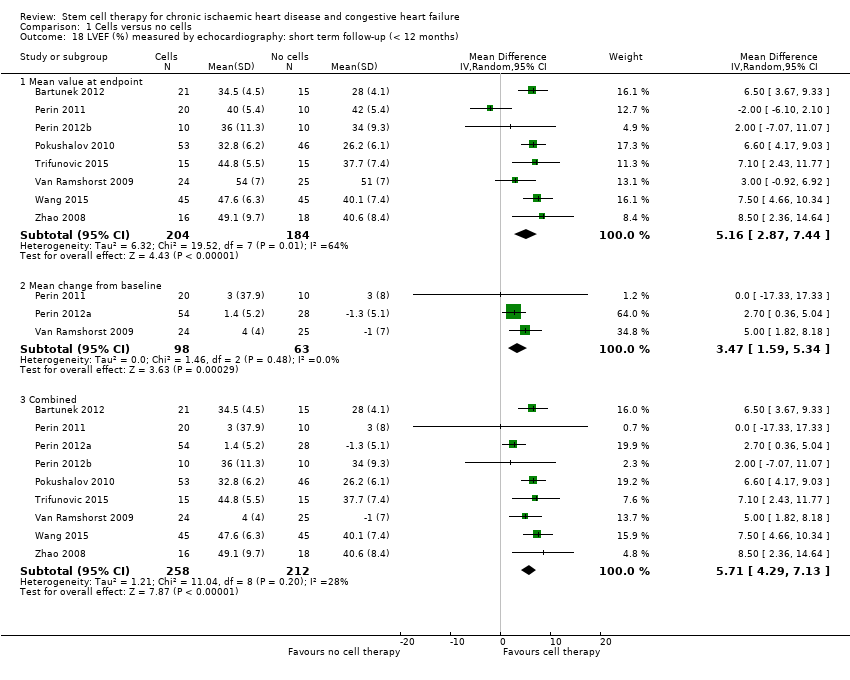

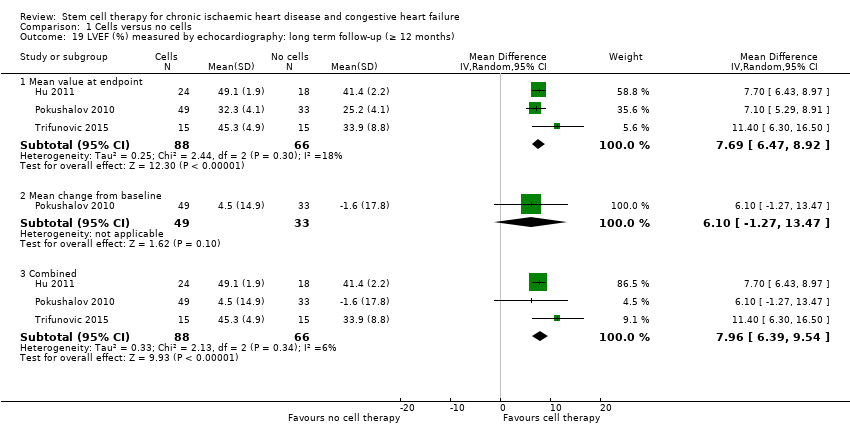

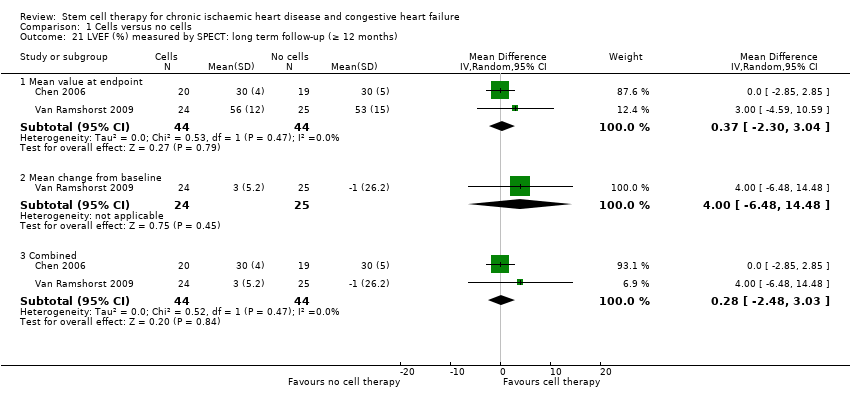

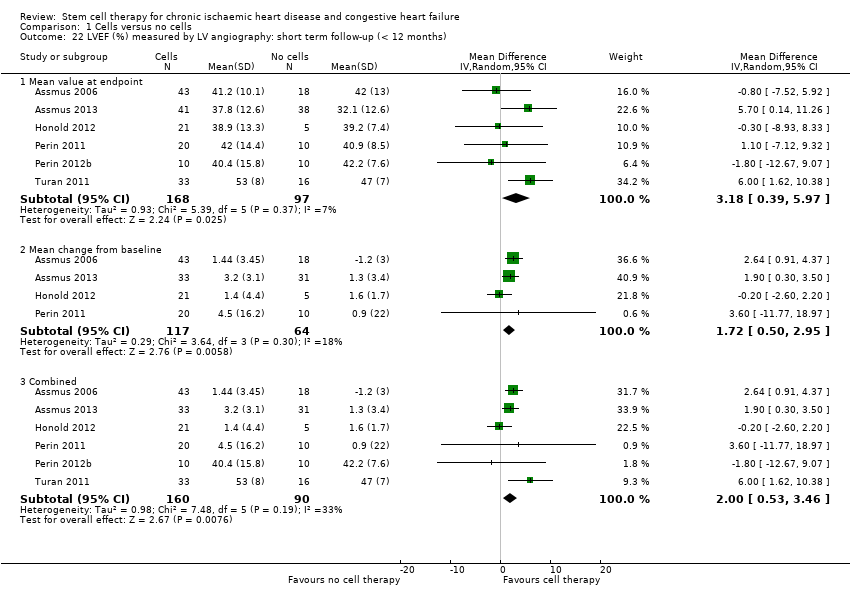

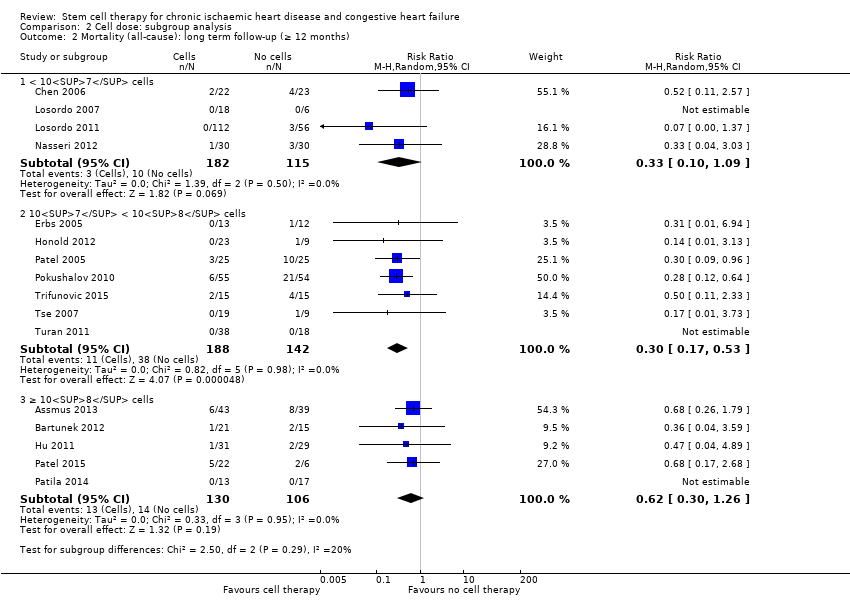

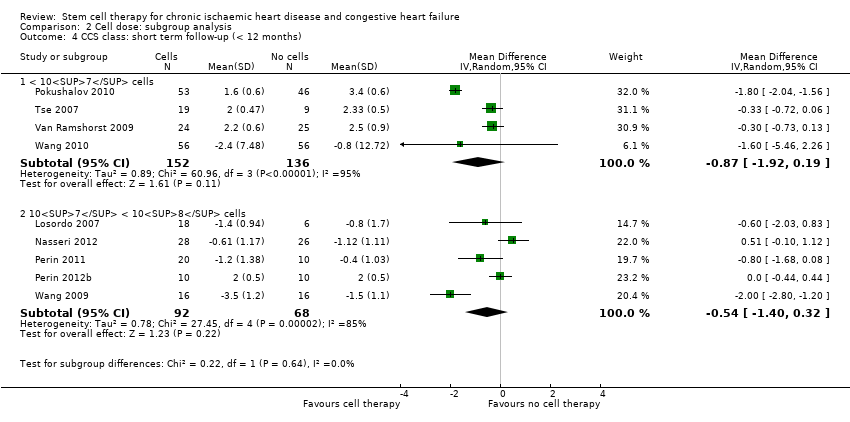

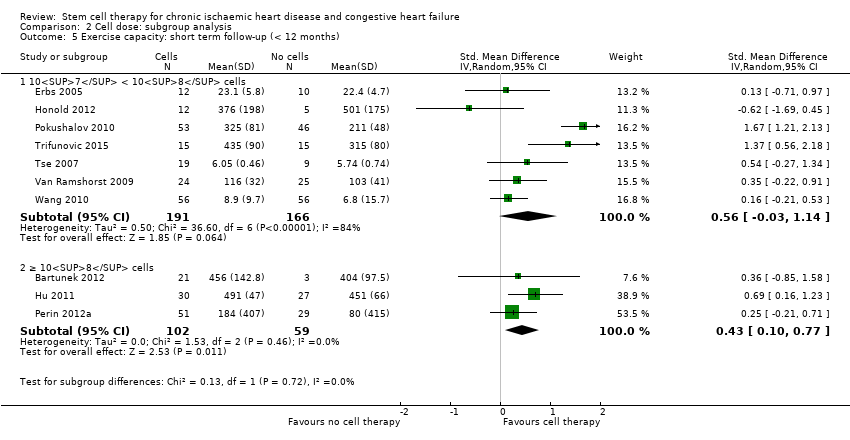

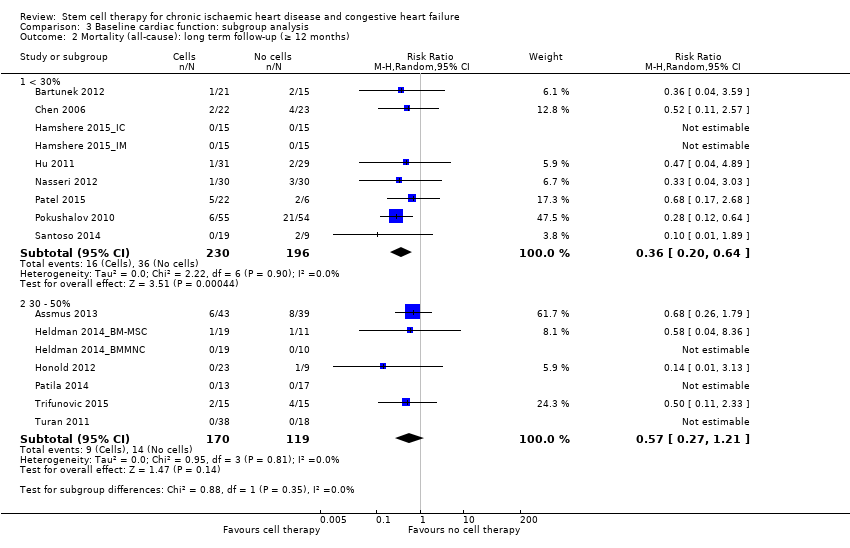

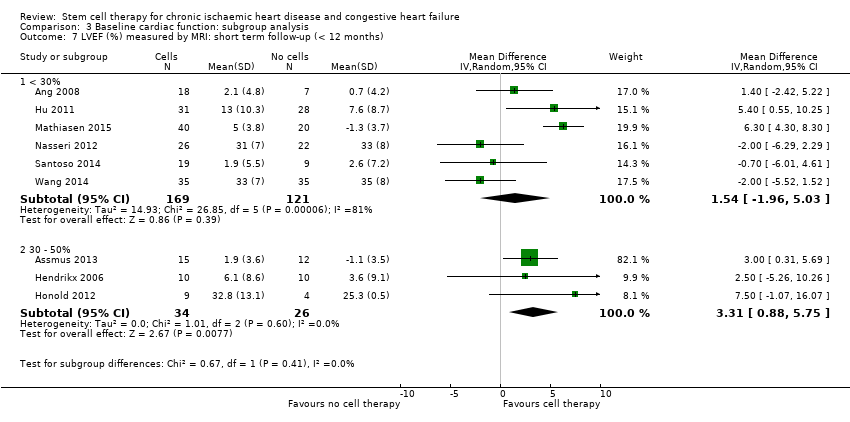

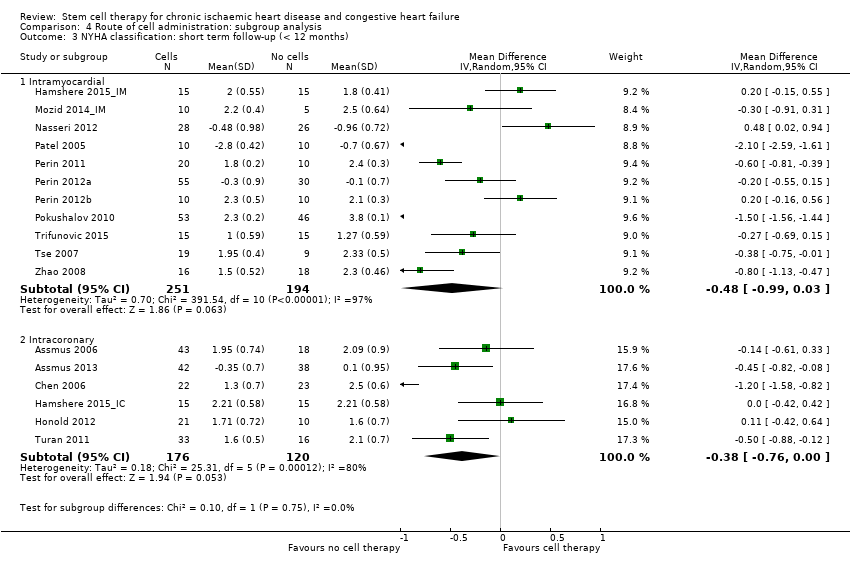

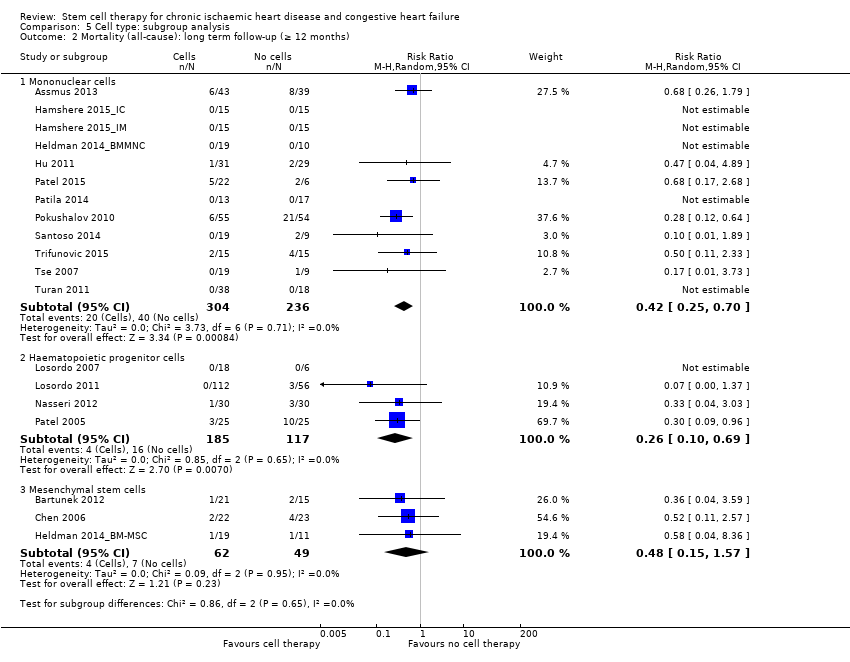

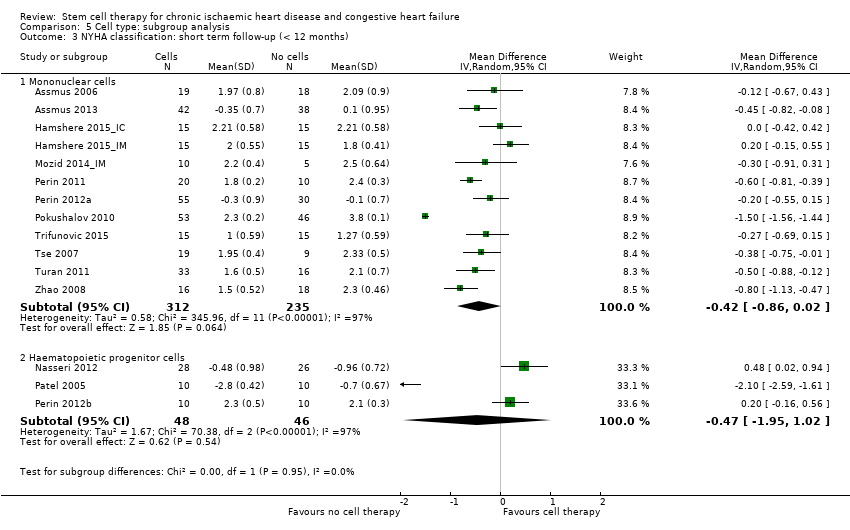

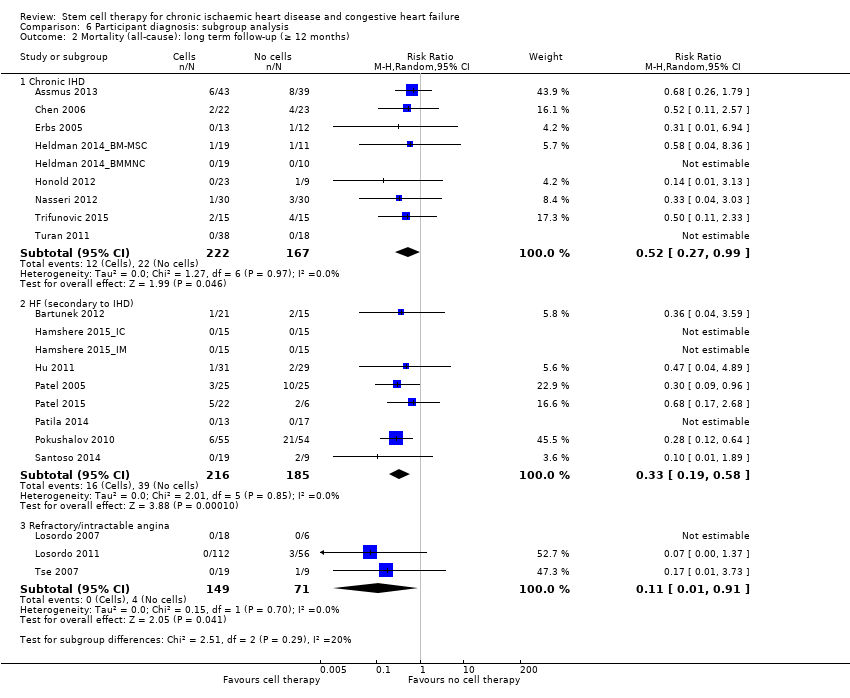

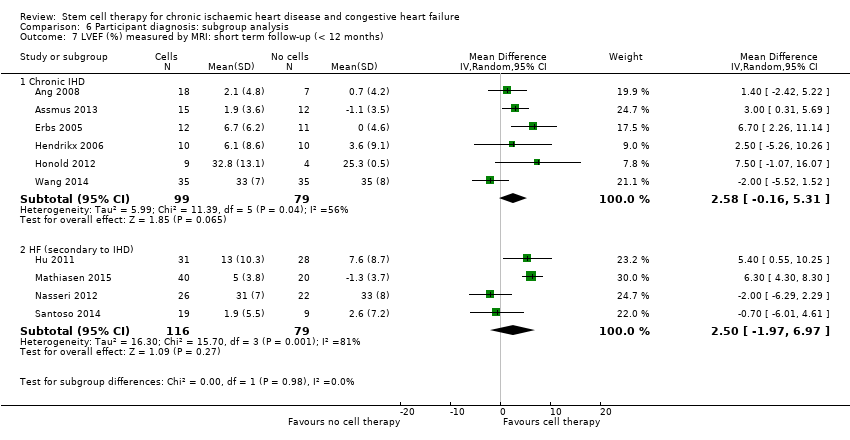

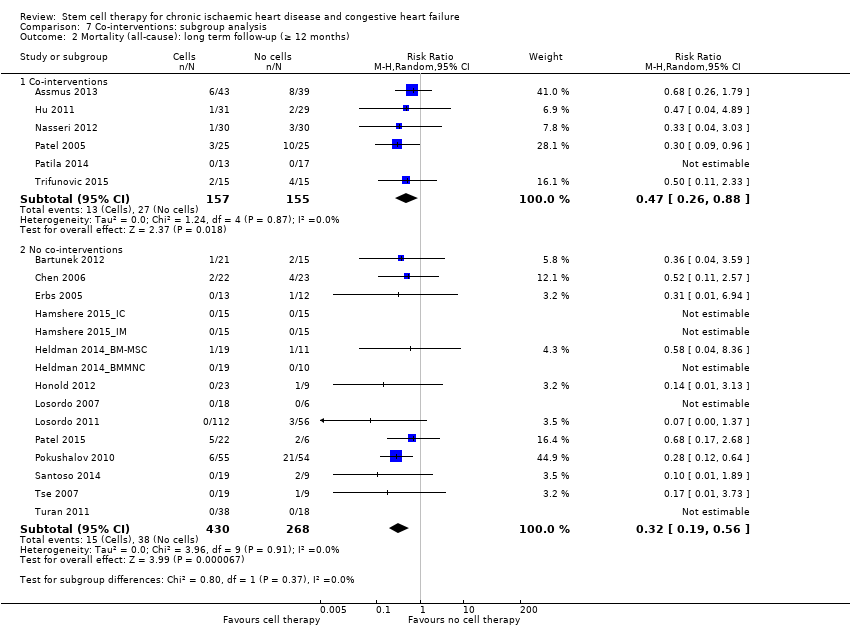

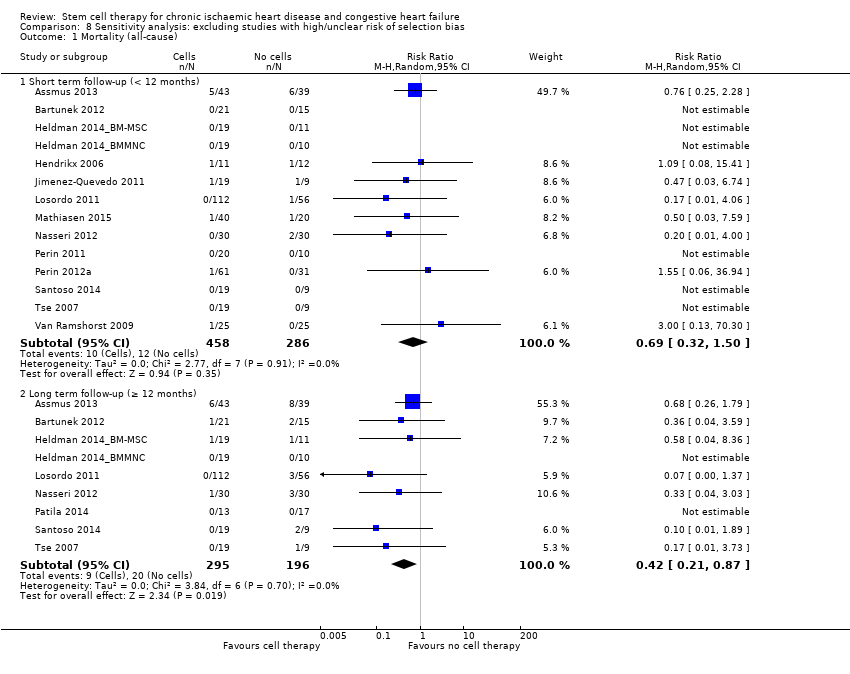

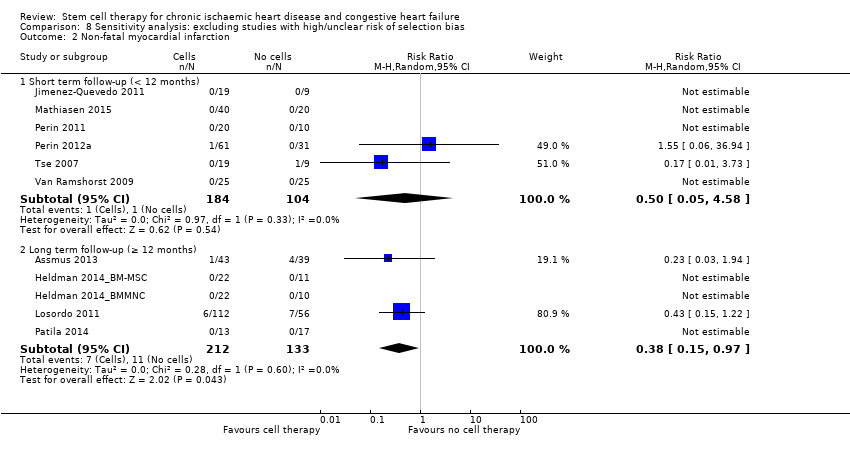

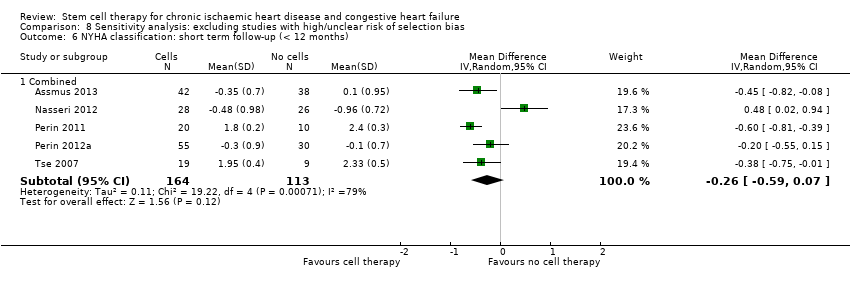

El tratamiento con células redujo la incidencia de mortalidad a largo plazo (≥ 12 meses) (cociente de riesgos [CR] 0,42; intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 0,21 a 0,87; participantes = 491; estudios = 9; I2 = 0%; pruebas de baja calidad). Los eventos adversos relacionados con el procedimiento asociados con el mapeo o con el procedimiento de inyección de células/placebo fueron poco frecuentes. El tratamiento con células también se asoció con una reducción a largo plazo en la incidencia de infarto de miocardio no mortal (CR 0,38; IC del 95%: 0,15 a 0,97; participantes = 345; estudios = 5; I2 = 0%; pruebas de baja calidad) y en la incidencia de arritmias (CR 0,42; IC del 95%: 0,18 a 0,99; participantes = 82; estudios = 1; pruebas de baja calidad). Sin embargo, no se encontraron pruebas de que el tratamiento con células afectara el riesgo de rehospitalización por insuficiencia cardíaca (CR 0,63; IC del 95%: 0,36 a 1,09; participantes = 375; estudios = 6; I2 = 0%; pruebas de baja calidad) ni de incidencia compuesta de mortalidad, infarto de miocardio no mortal o rehospitalización por insuficiencia cardíaca (CR 0,64; IC del 95%: 0,38 a 1,08; participantes = 141; estudios = 3; I2 = 0%; pruebas de baja calidad), ni afectara la fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo a largo plazo cuando se midió con imagenología de resonancia magnética (diferencia de medias ‐1,60; IC del 95%: ‐8,70 a 5,50; participantes = 25; estudios = 1; pruebas de baja calidad).

Conclusiones de los autores

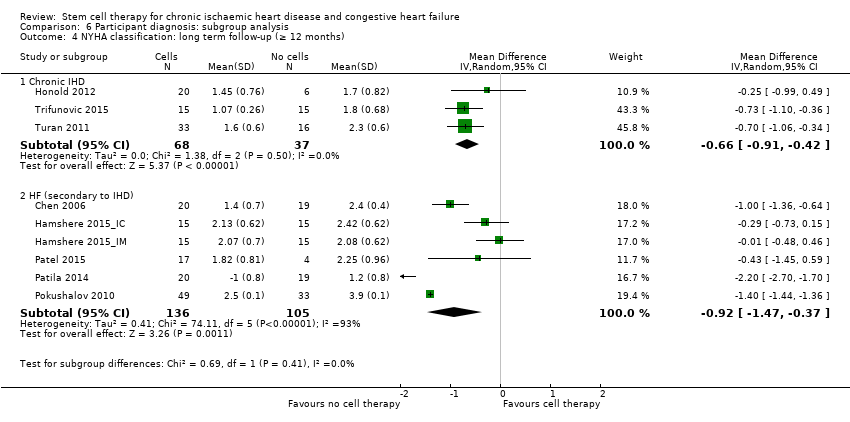

Esta revisión sistemática y metanálisis encontraron pruebas de baja calidad de que el tratamiento con células madre/progenitoras derivadas de la médula ósea reduce la mortalidad y mejora la fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo al seguimiento a corto y a largo plazo, y puede reducir la incidencia del infarto de miocardio no mortal y mejorar la New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification en los pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica crónica e insuficiencia cardíaca congestiva. Estos resultados se deben interpretar con cuidado porque las tasas de eventos fueron generalmente bajas, lo que dio lugar a falta de precisión.

PICOs

Resumen en términos sencillos

Tratamiento con células madre para la cardiopatía isquémica crónica y la insuficiencia cardíaca congestiva

Pregunta de la revisión

¿Las células adultas madre/progenitoras derivadas de la médula ósea son seguras y efectivas como tratamiento para la cardiopatía isquémica crónica y la insuficiencia cardíaca?

Antecedentes

El tratamiento actual de los pacientes que presentan cardiopatía e insuficiencia cardíaca se basa en medicamentos y, cuando es posible, la restauración de la irrigación de sangre en el corazón (revascularización) mediante la abertura de las arterias con un globo diminuto en un procedimiento llamado angioplastia primaria (o intervención coronaria percutánea) o mediante cirugía cardíaca (o injerto de derivación de las arterias coronarias). La revascularización ha reducido la tasa de mortalidad asociada con estos trastornos. En algunos pacientes la cardiopatía y los síntomas de insuficiencia cardíaca persisten incluso después de la revascularización. Recientemente, las células madre/progenitoras de la médula ósea se han investigado como un nuevo tratamiento para los pacientes con cardiopatía e insuficiencia cardíaca, reciban o no también tratamiento de revascularización.

Fecha de la búsqueda

Se efectuaron búsquedas en las bases de datos electrónicas de los ensayos controlados aleatorios relevantes hasta diciembre de 2015.

Características de los estudios

En esta revisión se incluyeron 38 ensayos controlados aleatorios con más de 1900 participantes, con 14 ensayos de cardiopatía isquémica crónica, 17 ensayos de insuficiencia cardíaca isquémica secundaria a cardiopatía y siete ensayos de angina resistente al tratamiento o intratable. La media de edad de los participantes varió de 55 a 70 años, y la proporción de participantes masculinos varió del 51% al 100%.

Resultados clave

Los resultados indicaron que el tratamiento con células derivadas de la médula ósea puede dar lugar a una reducción en las muertes de los participantes seguidos durante al menos 12 meses. En general los eventos adversos que ocurrieron alrededor del momento del tratamiento fueron poco frecuentes. Los participantes que recibieron tratamiento con células también presentaron menos ataques cardíacos y arritmias en comparación con los que no recibieron células. Sin embargo, el tratamiento con células no parece reducir el riesgo de rehospitalización por insuficiencia cardíaca ni el riesgo combinado de muerte, ataque cardíaco no mortal o rehospitalización, y no dio lugar a ninguna mejoría con respecto al tratamiento estándar en las pruebas de función cardíaca. Estos resultados indican que el tratamiento con células puede ser beneficioso en los pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica crónica o insuficiencia cardíaca, o ambos.

Calidad de la evidencia

La calidad de las pruebas fue baja, ya que el número de estudios y participantes incluidos actualmente no es suficientemente alto para establecer conclusiones consistentes. Trece estudios recibieron financiamiento comercial, de los cuales cuatro fueron patrocinados completamente, y 12 estudios no informaron que los participantes estuvieran cegados al tratamiento que recibieron. Se requieren estudios de investigación adicionales que incluyan un gran número de participantes para confirmar los resultados.

Conclusiones de los autores

Summary of findings

| Bone marrow‐derived cell therapy for people with chronic ischaemic heart disease and congestive heart failure | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with chronic ischaemic heart disease and congestive heart failure Comparison: no cell therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No cell therapy | Bone marrow‐derived cell therapy | |||||

| Mortality (all cause) Long‐term follow‐up (≥ 12 months) | 102 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 | RR 0.42 | 491 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The required information size of 1899 participants to detect a RRR of 35% has not been reached. |

| Periprocedural adverse events | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 1695 (34 studies) | See comment | Adverse events occurring during the mapping or cell/placebo injection procedure included ventricular tachycardia (7), ventricular fibrillation (1), atrial fibrillation (1), transient complete heart block (1), transient pulmonary oedema (3), thrombus on mapping catheter tip (1), visual disturbances (2), myocardial perforation (2), limited retrograde catheter‐related dissection of the abdominal aorta (1). |

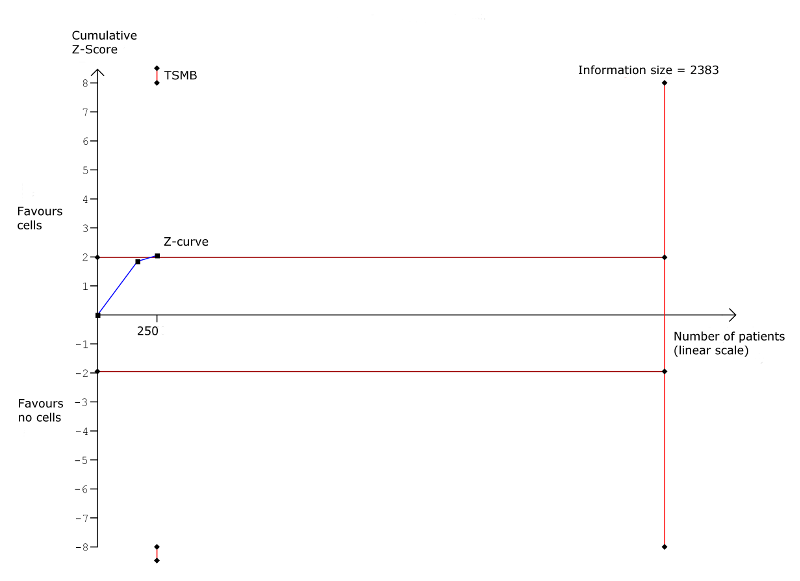

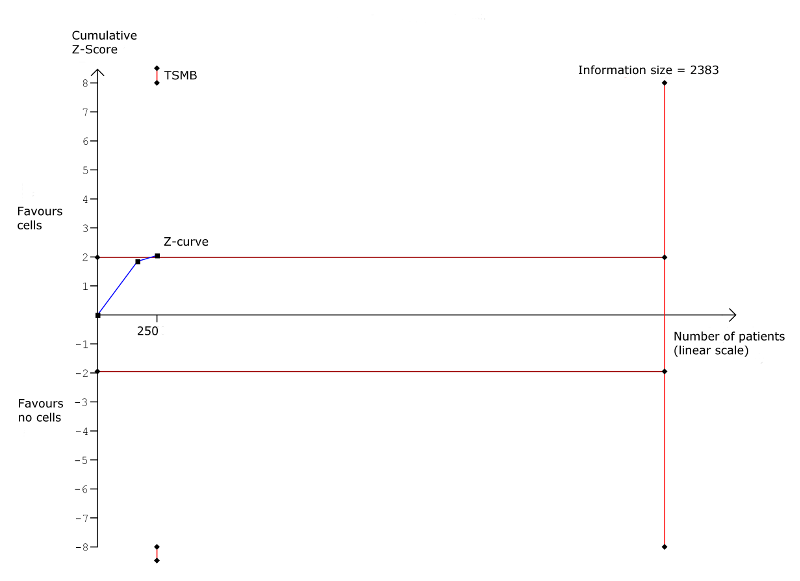

| Non‐fatal myocardial infarction Long‐term follow‐up (≥ 12 months) | 83 per 1000 | 31 per 1000 | RR 0.38 | 345 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The required information size of 2383 participants to detect a RRR of 35% has not been reached. |

| Rehospitalisation due to heart failure Long‐term follow‐up (≥ 12 months) | 155 per 1000 | 98 per 1000 | RR 0.63 | 375 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The required information size of 1193 participants to detect a RRR of 35% has not been reached. |

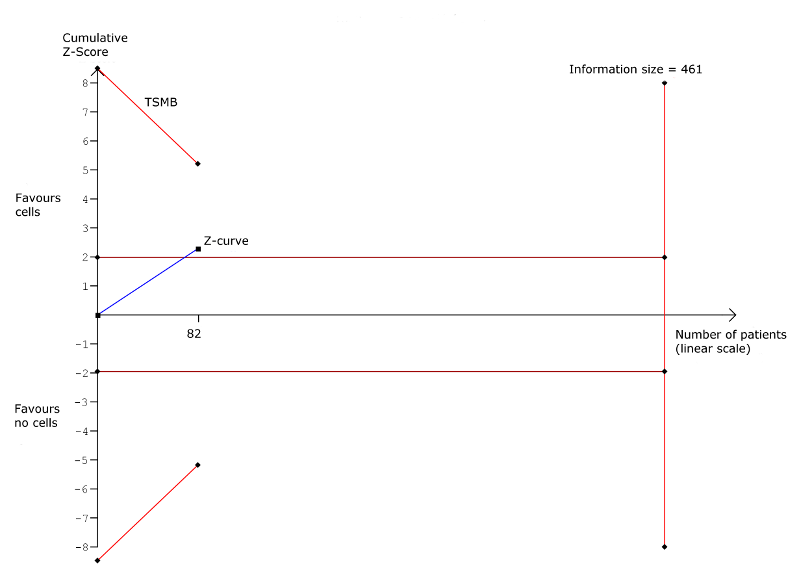

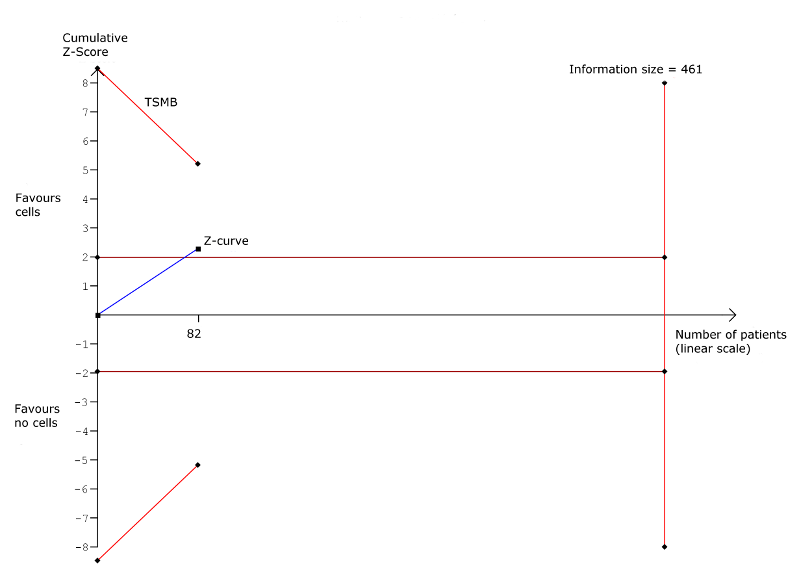

| Arrhythmias Long‐term follow‐up (≥ 12 months) | 333 per 1000 | 140 per 1000 | RR 0.42 | 82 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The required information size of 461 participants to detect a RRR of 35% has not been reached. |

| Composite MACE Long‐term follow‐up (≥ 12 months) | 350 per 1000 | 224 per 1000 | RR 0.64 | 141 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The required information size of 431 participants to detect a RRR of 35% has not been reached. |

| LVEF (%) measured by MRI Long‐term follow‐up (≥ 12 months) | ‐ | The mean LVEF (%) measured by MRI in the intervention groups was 1.6 lower (8.7 lower to 5.5 higher). | ‐ | 25 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The required information size of 322 participants to detect a mean difference of 4% has not been reached. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ¶Only studies with a low risk of selection bias are included. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Six trials received full or partial commercial funding, which could have resulted in a biased assessment of the intervention effect and were therefore deemed to have a high risk of bias. One trial was not blinded (high risk of performance bias) and had a high risk of attrition bias. | ||||||

Antecedentes

Descripción de la afección

La cardiopatía isquémica (CI) es una carga sanitaria importante en todo el mundo (BHF 2014). La supervivencia después del infarto de miocardio (IM) ha aumentado en años recientes debido a técnicas de revascularización de última generación como la intervención coronaria percutánea (ICP) y el injerto de derivación de las arterias coronarias (IDAC) (Skinner 2011). Por otra parte, el número de personas con insuficiencia cardíaca congestiva (ICC) se ha tornado rápidamente en una epidemia (Ambrosy 2014; Lloyd‐Jones 2002). Por lo tanto, la prevención de la progresión de la CI y el desarrollo de ICC aún es un desafío.

En la CI, puede haber tejido cicatrizal no contráctil que ha reemplazado el miocardio dañado, lo que podría causar daño adicional. El corazón también puede evitar la muerte de más cardiomiocitos al reducir las exigencias de energía de la contracción, lo que da lugar a un miocardio que no se contrae o en hibernación. Esta respuesta fisiológica característica al estrés hipóxico crónico, que es identificable por las anomalías en la función contráctil, se puede revertir potencialmente por la revascularización del miocardio en hibernación para restaurar la función cardíaca (Taggart 2012). En algunos casos, la revascularización no es posible o puede no ser completa, y en los casos con miocardiopatía no isquémica la revascularización no es relevante y los síntomas de isquemia miocárdica crónica, a veces con angina de pecho resistente al tratamiento, aún están presentes (Taggart 2012).

Enfoques alternativos y complementarios en el tratamiento de la ICC están en desarrollo, en forma de tratamientos con células para la ICC. La justificación para desarrollar los tratamientos con células para la CI se basa en la noción de que el corazón tiene una capacidad limitada para repararse por sí mismo después de una lesión grave. Estudios preclínicos y clínicos han indicado que los tratamientos con células podrían revertir potencialmente la disfunción ventricular izquierda en la CI crónica y la ICC (Heldman 2014; Perin 2012a).

Descripción de la intervención

El procedimiento actualmente es el siguiente: la médula ósea se extrae del receptor o las células madre/progenitoras se movilizan a la circulación mediante un factor estimulante del crecimiento (conocido con mayor frecuencia como factor estimulante de colonias de granulocitos [G‐CSF, por sus siglas en inglés]) (Assmus 2006; Erbs 2005). En el primer procedimiento, las células por lo general se recolectan (a veces bajo anestesia general) del hueso pélvico, con el uso de agujas de succión grandes. Las células madre/progenitoras posteriormente se separan de otras células de la médula ósea en condiciones estériles (Assmus 2006). La obtención de las células de la médula ósea y los procedimientos de separación de las células pueden demorar varias horas. En el procedimiento de movilización con G‐CSF, las células progenitoras o las células mononucleares se recogen como una muestra de sangre y luego se separan de otras células sanguíneas en condiciones estériles (Erbs 2005). En ambos procedimientos, las células se infunden directamente en las arterias coronarias o en el corazón del receptor (Ang 2008; Hamshere 2015). El primer procedimiento administra las células a las arterias coronarias a través de un catéter balón especial durante la angioplastia (p.ej. intervención coronaria percutánea) mediante una técnica de interrupción del flujo (Ang 2008; Hamshere 2015). El segundo procedimiento administra las células en el músculo cardíaco durante un procedimiento similar a la angioplastia con el uso de mapeo electromecánico y una inyección intramiocárdica directa (p.ej. sistema NOGA) o durante la cirugía cardíaca (p.ej. injerto de derivación de las arterias coronarias) (Ang 2008; Hamshere 2015), aunque esta opción puede estar limitada por los costos elevados asociados con el procedimiento percutáneo del NOGA. El intervalo entre la obtención de las células y su reinfusión varía; algunas se administran frescas y a otras se les realiza alguna forma de cultivo y expansión ex vivo que podría tomar de dos a tres semanas (Assmus 2006; Bartunek 2012; Mathiasen 2015).

Generalmente un hematólogo realiza la obtención de las células. Un científico o técnico especializado realiza la separación de las células madre de las otras células de la médula ósea, y el cardiólogo o el cirujano cardíaco realizan la infusión o la inyección intramiocárdica de las células.

Los efectos adversos asociados con la administración de las células de la médula ósea sanguíneas como tratamiento para los pacientes con CI crónica o ICC son poco frecuentes y en general no son graves (Behfar 2014). En los ensayos en los que el G‐CSF se administra antes de la obtención de las células madre se pueden presentar complicaciones transitorias causadas por el tratamiento con G‐CSF. Sin embargo, no se han informado efectos adversos a largo plazo.

En la actualidad, este tratamiento sólo está disponible en establecimientos asociados con la investigación aunque es posible que, si se confirma la efectividad a largo plazo, este procedimiento podría estar disponible para algunos o todos los pacientes con cardiopatía crónica, debido a que la obtención de la médula ósea y la sangre periférica es un procedimiento estándar utilizado en el trasplante de médula ósea. Los costos pueden ser elevados, según los procedimientos utilizados, y actualmente se relacionan con los costos de la obtención de las células y su procesamiento (aproximadamente la décima parte del costo global del ensayo). La posibilidad de un ensayo controlado aleatorio multicéntrico grande (ECA) está limitada por los fondos y por los resultados contradictorios de los ECA anteriores.

De qué manera podría funcionar la intervención

Los ensayos clínicos en los que se les han administrado células derivadas de la médula ósea a pacientes con CI o ICC han obtenido resultados divergentes, por lo que el mecanismo de acción de dichos tratamientos aún no está claro. Por lo tanto, la selección del tipo de células óptimo y de la cohorte de pacientes óptimos para ser tratados es un reto. Aunque la incorporación en los vasos sanguíneos y la generación directa de cardiomiocitos se han propuesto como mecanismos de acción (Beltrami 2003; Carr 2008; Martin‐Rendon 2008a; Mathur 2004; Stuckey 2006; Yoon 2005), actualmente se acepta que un mecanismo paracrino puede ser la contribución principal para promover la reparación cardíaca y limitar la fibrosis en el miocardio dañado (Ibrahim 2016; Li 2012).

Por qué es importante realizar esta revisión

Los tratamientos con células tienen la posibilidad de convertirse en una forma de tratamiento nueva y apasionante para muchas enfermedades. La cardiopatía es uno de los contextos clínicos en los que es posible considerar esta nueva forma de tratamiento, aunque aún no se ha definido la función clínica exacta del tratamiento con células madre. El tratamiento con células para la cardiopatía isquémica es un tratamiento experimental que no tiene una amplia disponibilidad y no es parte de la práctica clínica estándar. Actualmente no hay guías clínicas para la administración de los tratamientos con células para la cardiopatía isquémica y la insuficiencia cardíaca. Las pruebas de ensayos y revisiones sistemáticas más antiguos han indicado que el tratamiento con células puede dar lugar a algunas mejorías en comparación con el tratamiento convencional cuando se mide a través de pruebas alternativas de la función cardíaca (Abdel‐Latif 2007; Assmus 2006; Chen 2006; Jeevanantham 2012). Revisiones sistemáticas y metanálisis más recientes han mostrado resultados contradictorios (Afzal 2015; Fisher 2015b). Una revisión Cochrane reciente concluyó que no hay pruebas suficientes de un efecto beneficioso del tratamiento con células en los pacientes con infarto agudo de miocardio; la mayoría de las pruebas provinieron de ensayos pequeños que no mostraron diferencias en resultados clínicamente relevantes (Fisher 2015a). Sin embargo, al parecer hay pruebas consistentes que indican que los tratamientos con células tuvieron un efecto beneficioso en los pacientes con insuficiencia cardíaca (Fisher 2016).

Una revisión Cochrane del tratamiento con células en pacientes con CI crónica e ICC incluyó 23 ECA y encontró algunas pruebas de que las células derivadas de la médula ósea mejoran la fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo (FEVI), reducen el número de muertes y se asocian con mejores medidas de funcionamiento a largo plazo (Fisher 2014). Desde la publicación de la revisión original se han publicado varios ensayos nuevos clave (Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Nasseri 2012; Patel 2015; Patila 2014; Santoso 2014; Trifunovic 2015; Wang 2014; Wang 2015). Es importante actualizar la revisión con estos nuevos ensayos para reevaluar y mejorar la calidad de las pruebas disponibles.

Objetivos

La evaluación crítica de las pruebas clínicas sobre la seguridad y la eficacia de las células madre/progenitoras derivadas de la médula ósea adulta y autólogas como tratamiento para la CI crónica y la ICC.

Métodos

Criterios de inclusión de estudios para esta revisión

Tipos de estudios

Ensayos controlados con asignación aleatoria (ECA).

Tipos de participantes

Pacientes con diagnóstico clínico de CI o ICC, con la exclusión de los pacientes con infarto agudo de miocardio. Los estudios que evaluaron la enfermedad isquémica y no isquémica sólo se incluyeron si fue posible extraer por separado los datos de los participantes con enfermedad isquémica.

Tipos de intervenciones

Estudios que incluyeran la administración de células madre/progenitoras derivadas de la médula ósea adulta y autólogas de forma aislada o en combinación con otras intervenciones, como la cirugía cardíaca, como tratamiento para la CI o la ICC.

Los participantes del brazo de tratamiento comparador del ensayo recibieron ninguna intervención o placebo (p.ej. el medio en el que las células madre estaban suspendidas o plasma). Los ensayos en los que además se administraron cointervenciones (p.ej. IDAC, ICP, G‐CSF, tratamiento con onda de choque extracorpórea) fueron elegibles siempre que las cointervenciones fueran iguales en ambos brazos y se les administraran a una proporción equivalente de participantes.

En resumen:

-

cualquier célula madre/progenitora derivada de la médula ósea adulta humana y autóloga

-

cualquier dosis única

-

cualquier método de aislamiento de las células madre/progenitoras

-

cualquier vía de administración

-

cualquier cointervención

-

repetición de la intervención o múltiples dosis

Tipos de medida de resultado

Resultados primarios

-

Mortalidad

-

Eventos adversos relacionados con el procedimiento (definidos como los que ocurren en el momento de la aspiración de la médula ósea o de la administración del tratamiento con células [o placebo], o los eventos adversos documentados en el transcurso de los 30 días de tratamiento)

Resultados secundarios

-

Morbilidad: IM no mortal, rehospitalización por insuficiencia cardíaca (IC), arritmias, medida compuesta de eventos adversos clínicos graves (MACE, mortalidad, IM no mortal, o rehospitalización por IC)

-

Calidad de vida (CdV) relacionada con la salud

-

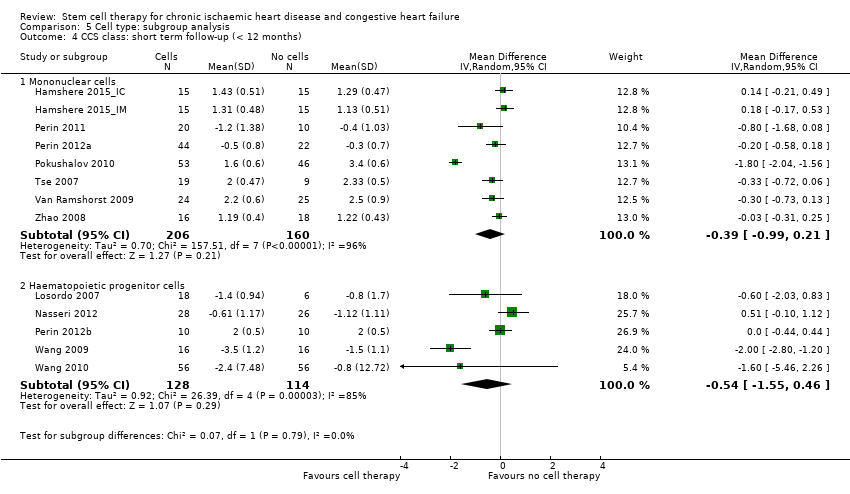

Estado funcional (p.ej. clasificación de la New York Heart Association [NYHA], clase de la Canadian Cardiovascular Society [CCS], capacidad de ejercicio)

-

Fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo (FEVI).

Los resultados beneficiosos se dividieron en variables de evaluación alternativas o basadas en datos clínicos. En el estadio del protocolo de esta revisión, se había intentado considerar las variables de evaluación clínicas y alternativas a los 30 días, seis meses y 12 meses después del inicio; sin embargo, lo anterior no fue posible debido a la variación en los períodos de seguimiento informados en los estudios individuales. Por lo tanto, se estratificaron los datos de resultado en seguimiento a corto plazo (hasta 12 meses) y a largo plazo (12 meses o más). El alcance de esta versión de la revisión fue evaluar el efecto clínico beneficioso o perjudicial de los tratamientos con células en los pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica e insuficiencia cardíaca, por lo que la revisión se centró en los resultados clínicos. Sin embargo, el resultado alternativo FEVI es una medida alternativa estándar ampliamente informada de la función cardíaca y se ha mantenido como punto de referencia en otros ensayos y revisiones sistemáticas de la IC. Se excluyeron otros resultados alternativos diferentes de la FEVI informados en las versiones anteriores de esta revisión, a saber, injerto funcionante y supervivencia de las células infundidas, volumen sistólico final, volumen diastólico final, puntuación de movimiento de la pared e índice de volumen sistólico, según el Grupo Cochrane de Corazón (Cochrane Heart Group). Sin embargo, se consideró que los resultados alternativos relevantes como los volúmenes del ventrículo izquierdo pueden ser más significativos que la FEVI y como tal, estos resultados alternativos se considerarán en la próxima actualización de esta revisión.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified a total of 20,646 references from the electronic database searches. De‐duplication and removal of all clearly irrelevant references by the Information Specialist (CD) excluded 14,955 references. Initial screening of the remaining 5691 citations against inclusion criteria excluded a further 5486 references. Of the remaining 205 citations, we subsequently excluded 70 references (describing 54 independent studies), as they did not fully meet the inclusion criteria (see Excluded studies). Five further references described four independent study protocols (see Ongoing studies). Ten studies (12 references) were published in abstract form only, and although they appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, they did not contain sufficient data for inclusion; we have identified these as Studies awaiting classification. The remaining 118 citations describe a total of 38 independent RCTs (see Included studies). A summary of study classification is displayed in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

PRISMA flow diagram.

Searching of ongoing trial databases identified 1302 trial records. De‐duplication and removal of clearly irrelevant trials by the Information Specialist (CD) excluded 949 records. Of the remaining 353 records, 22 described included studies and 31 were ongoing trials that met the eligibility criteria and are shown in Ongoing studies.

Included studies

Thirty‐eight studies met the inclusion criteria for this review, including a total of 1907 randomised participants (1114 bone marrow‐derived stem/progenitor cells and 793 controls) who were assessed for the primary outcomes of the study. Sixteen independent trials are new to this review update (Bartunek 2012; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM; Nasseri 2012; Patel 2015; Patila 2014; Santoso 2014; Trifunovic 2015; Wang 2014; Wang 2015), representing an approximately 70% increase in the number of included participants from the previous version of the review. One study included in the original review was excluded in this update, as the co‐intervention of G‐CSF administered to the cell therapy group was not given to the control group (Kang 2006). See Table 1 for a summary of study participants.

| Study ID | Country of study | Patient population | Mean (SD) age of participants (years) | % Male | No. randomised participants receiving intervention | No. randomised participants receiving comparator | Mean duration of follow‐up |

| UK | CIHD (> 1 chronic myocardial scar; elective CABG) | BMMNC‐IM: 64.7 (8.7) BMMNC‐IC: 62.1 (8.7) Controls: 61.3 (8.3) | BMMNC‐IM: 71.4% BMMNC‐IC: 90.5% Controls: 90.0% | 42 (21 IM, 21 IC) | 21 | 6 months | |

| Germany | CIHD (MI > 3 months; LV dysfunction) | BMMNC: 59 (12) CPC: 54 (12) Controls: 61 (9) | BMMNC: 89% CPC: 79% Controls: 100% | 52 (28 MNC, 24 CPC) | 23 | 3 months | |

| Germany | CIHD (MI > 3 months; LVEF < 50%; NYHA class II or greater) | BMMNC‐LDSW: 65 (12) BMMNC‐HDSW: 58 (11) Controls‐LDSW: 60 (10) Controls‐HDSW: 63 (10) | BMMNC‐LDSW: 77% BMMNC‐HDSW: 86% Controls‐LDSW: 80% Controls‐HDSW: 90% | 43 (22 LDSW, 21 HDSW) | 39 (20 LDSW, 19 HDSW) | 45.7 (17) months | |

| Belgium/ Serbia/ Switzerland | HF (LVEF 15% to 40%; ischaemic event > 2 months) | BM‐MSC: 55.3 (SE 10.4) Controls: 58.7 (SE 8.2) | BM‐MSC: 90.5% Controls: 86.7% | 32 | 15 | 24 months | |

| China | CIHD (isolated, chronic LAD; LVEF < 40%) | BM‐MSC: 59.3 (6.8) Controls: 57.8 (7.2) | BM‐MSC: 88% Controls: 92% | 24 | 24 | 12 months | |

| Germany | CIHD (chronic total occlusion; myocardial ischaemia) | CPC: 63 (7) Controls: 61 (9) | CPC: 71% Controls: 86% | 14 | 14 | 15 months | |

| UK | HF (NYHA class II‐IV; no revascularisation options) | BMMNC: n/r Controls: n/r | BMMNC: n/r Controls: n/r | 15 | 15 | 12 months | |

| UK | HF (NYHA class II‐IV; no revascularisation options) | BMMNC: n/r Controls: n/r | BMMNC: n/r Controls: n/r | 15 | 15 | 12 months | |

| USA | CIHD (chronic MI; LV dysfunction) | BMMNC: 61.1 (8.4) Controls: 61.3 (9.0) | BMMNC: 89.5% Controls: 100% | 22 | 10 | 12 months | |

| USA | CIHD (chronic MI; LV dysfunction) | BM‐MSC: 57.1 (10.6) Controls: 60.0 (12.0) | BM‐MSC: 94.7% Controls: 90.9% | 22 | 11 | 12 months | |

| Belgium | CIHD (transmural MI; LV dysfunction; elective CABG) | BMMNC: 63.2 (8.5) Controls: 66.8 (9.2) | BMMNC: 100% Controls: 70% | 11 | 12 | 4 months | |

| Germany | CIHD (MI > 3 months; LV regional wall motion abnormality) | CPC: 53.4 (12.3) Controls: 58.8 (7.3) | CPC: 82% Controls: 100% | 23 | 10 | 60 months | |

| China | HF (MI > 3 months; LVEF < 30%; elective CABG) | BMMNC: 56.6 (9.7) Controls: 58.3 (8.9) | BMMNC: 88% Controls: 96% | 31 | 29 | 12 months | |

| Spain | Refractory angina (CCS class II‐IV) | CD133+: median 70.0 Controls: median 58.2 | CD133+: 78.9% Controls: 100% | 19 | 9 | 6 months | |

| USA | Refractory angina (CCS class III‐IV) | CD34+/controls pooled: 62.4 (range 48 to 84) | CD34+/controls pooled: 80% | 18 (6 LD, 6 MD 6, HD) | 6 | 6 months | |

| USA | Refractory angina (CCS class III‐IV) | CD34+/LD: 61.3 (9.1) CD34+/HD: 59.8 (9.2) Controls: 61.8 (8.5) | CD34+/LD: 83.6% CD34+/HD: 87.5% Controls: 89.3% | 112 (56 LD, 56 HD) | 56 | 12 months | |

| Denmark | HF (NYHA class II‐III; LVEF < 45%; no revascularisation options) | BM‐MSC: 66.1 (7.7) Controls: 64.2 (10.6) | BM‐MSC: 90% Controls: 70% | 40 | 20 | 6 months | |

| UK | HF (NYHA class II‐IV; no revascularisation options) | BMMNC/controls pooled (16 participants): 70 (10) | BMMNC/controls pooled (16 participants): 94% | 14 | 2 | 6 months | |

| UK | HF (NYHA class II‐IV; no revascularisation options) | BMMNC/controls pooled (18 participants): 64 (9) | BMMNC/controls pooled (18 participants): 100% | 10 | 8 | 6 months | |

| Germany | HF (LVEF < 35%; elective CABG) | CD133+: 61.9 (7.3) Controls: 62.7 (10.6) | CD133+: 93% Controls: 97% | 30 | 30 | 6 months | |

| Argentina | HF (LVEF < 35%; NYHA class III‐IV; elective CABG) | CD34+: 64.8 (7.1) Controls: 63.6 (5.2) | CD34+: 80% Controls: 80% | 25 | 25 | 10 years | |

| USA/Germany/India | HF (LVEF < 40%; NYHA class III‐IV) | BMAC: 58.5 (12.7) Controls: 52.7 (8.5) | BMAC: 91.7% Controls: 100% | 24 | 6 | 12 months | |

| Finland | HF (LVEF 15% to 40%; NYHA class II‐IV; elective CABG) | BMMNC: median 65 (range 57 to 73) Controls: median 64 (range 58 to 70) | BMMNC: 94.7% Controls: 95.0% | 20 | 19 | 12 months | |

| USA | HF (angina/HF symptoms; chronic CAD; LVEF < 40%; no revascularisation options) | BMMNC: 56.3 (8.6) Controls: 60.5 (6.4) | BMMNC: 50% Controls: 80% | 20 | 10 | 6 months | |

| USA | HF (CCS class II‐IV or NYHA class II‐III, or both; LVEF < 45%; no revascularisation options) | BMMNC: 64.0 (10.9) Controls: 62.3 (8.3) | BMMNC: 86.9% Controls: 93.7% | 61 | 31 | 6 months | |

| USA | HF (CCS class II‐IV or NYHA class II‐III, or both; LVEF < 45%; no revascularisation options) | ALDH+: 58.2 (6.1) Controls: 57.8 (5.5) | ALDH+: 90% Controls: 80% | 10 | 10 | 6 months | |

| Russia | HF (LVEF < 35%; no revascularisation options) | BMMNC: 61 (9) Controls: 62 (5) | BMMNC: 87% Controls: 85% | 55 | 54 | 12 months | |

| Indonesia/China | HF (NYHA class III‐IV; LVEF < 40%; no revascularisation options) | BMMNC: 58 (5.9) Controls: 60 (5.6) | BMMNC: 95% Controls: 100% | 19 | 9 | 6 months | |

| Serbia | CIHD (MI < 30 days; LVEF < 40%; NYHA class III‐IV; elective CABG) | BMMNC: 53.8 (10.1) Controls: 60.0 (6.8) | BMMNC: 93.3% Controls: 93.3% | 15 | 15 | Median 5 years (IQR 2.5 to 7.5) | |

| China/Australia | Refractory angina (CCS class III‐IV) | BMMNC: 65.2 (8.3) Controls: 68.9 (6.3) | BMMNC: 79% Controls: 88% | 19 | 9 | 6 months | |

| Germany | CIHD (MI > 3 months; LV dysfunction) | BMMNC: 62 (10) Controls: 60 (9) | BMMNC: 52.6% Controls: 55.6% | 38 | 18 | 12 months | |

| The Netherlands | Refractory angina (CCS class II‐IV) | BMMNC: 64 (8) Controls: 62 (9) | BMMNC: 92% Controls: 80% | 25 | 25 | 6 months | |

| China | Refractory angina (MI > 1 month) | CD34+: 60.6 (n/r) Controls: 60.0 (n/r) | CD34+: 56.3% Controls: 63.3% | 16 | 16 | 6 months | |

| China | Refractory angina (CCS class III‐IV) | CD34+: range 42 to 80 Controls: range 43 to 80 | CD34+: 51.8% Controls: 50.0% | 56 | 56 | 6 months | |

| China | CIHD (LVEF < 35%) | CD133+: n/r Controls: n/r | CD133+: n/r Controls: n/r | 35 | 35 | 6 months | |

| China | CIHD (multivessel disease; MI > 4 weeks; elective CABG) | BMMNC: 61.4 (7.5) Controls: 62.9 (6.9) | BMMNC: 82% Controls: 78% | 45 | 45 | 6 months | |

| China | CIHD (MI > 6 months) | BMMNC: 54.8 (11.5) Controls: 56.3 (7.9) | BMMNC: 96% Controls: 96% | 24 | 23 | 6 months | |

| China | HF (LVEF < 40%; elective CABG) | BMMNC: 60.3 (10.4) Controls: 59.1 (15.7) | BMMNC: 83.3% Controls: 83.3% | 18 | 18 | 6 months |

ALDH: aldehyde dehydrogenase

BMAC: bone marrow aspirate concentrate

BMMNC: bone marrow mononuclear cells

BM‐MSC: bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting

CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society

CIHD: chronic ischaemic heart disease

CPC: circulating progenitor cells

EF: ejection fraction

HD: high dose

HDSW: high dose shockwave

HF: heart failure

IC: intracoronary

IM: intramyocardial

IQR: interquartile range

LAD: left ventricular assist device

LD: low dose

LDSW: low dose shockwave

LV: left ventricular

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

MD: medium dose

MI: myocardial infarction

MNC: mononuclear cells

n/r: not reported

NYHA: New York Heart Association

SD: standard deviation

SE: standard error

SW: shockwave

The mean age of participants ranged from 55 to 70 years, and the proportion of men ranged from 50.9% to 100%. All trials were presented as full journal articles, with the exception of three trials that were published in the form of a conference abstract (Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Wang 2014), and two trials that reported additional long‐term follow‐up results in abstract form only (Assmus 2013; Patel 2005). Nine studies were multicentre trials (Bartunek 2012; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011; Patel 2015; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Santoso 2014; Tse 2007). Studies were based worldwide, including China (Chen 2006; Hu 2011; Wang 2009; Wang 2010; Wang 2014; Wang 2015; Yao 2008; Zhao 2008), Germany (Assmus 2006; Assmus 2013; Erbs 2005; Honold 2012; Nasseri 2012; Turan 2011), the United States (Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b), the United Kingdom (Ang 2008; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM), Spain (Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011), Belgium (Hendrikx 2006), Denmark (Mathiasen 2015), the Netherlands (Van Ramshorst 2009), Finland (Patila 2014), Serbia (Trifunovic 2015), Russia (Pokushalov 2010), Argentina (Patel 2005), Hong Kong/Australia (Tse 2007), Indonesia/China (Santoso 2014), Belgium/Serbia/Switzerland (Bartunek 2012), and USA/Germany/India (Patel 2015). Two studies included publications in Chinese (Hu 2011; Wang 2009), which were translated into English for this review.

Fourteen studies included participants with chronic IHD (Ang 2008; Assmus 2006; Assmus 2013; Chen 2006; Erbs 2005; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hendrikx 2006; Honold 2012; Trifunovic 2015; Turan 2011; Wang 2014; Wang 2015; Yao 2008), normally defined as multivessel disease with persistent ischaemia and at least 30 days from the last MI. Seventeen studies included participants with CHF, defined as severe ischaemic HF and postinfarction HF (secondary to IHD) (Bartunek 2012; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Hu 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM; Nasseri 2012; Patel 2005; Patel 2015; Patila 2014; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Pokushalov 2010; Santoso 2014; Zhao 2008), and seven studies were of people with intractable or refractory angina (Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011; Tse 2007; Van Ramshorst 2009; Wang 2009; Wang 2010). One trial also included people with non‐ischaemic heart disease (Patel 2015), but reported results separately so that only participants with ischaemic disease are included in this review. All trials maintained participants with a standard set of drugs including aspirin, clopidogrel, heparin, blockers, statins, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, nitrates, and/or diuretics.

Duration of follow‐up ranged from three months (Assmus 2006), four months (Hendrikx 2006), six months (Ang 2008; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2007; Mathiasen 2015; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM; Nasseri 2012; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Santoso 2014; Tse 2007; Van Ramshorst 2009; Wang 2009; Wang 2010; Wang 2014; Wang 2015; Yao 2008; Zhao 2008), 12 months (Chen 2006; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hu 2011; Losordo 2011; Patel 2015; Patila 2014; Pokushalov 2010; Turan 2011), 15 months (Erbs 2005), 24 months (Bartunek 2012) up to a median 45 (17) months (Assmus 2013), 60 months (Honold 2012; Trifunovic 2015), and 10 years (Patel 2005).

See Table 2 for a summary of study interventions. Twenty‐seven trials isolated the stem cells by bone marrow aspiration and further separation of the mononuclear cells using density gradient centrifugation (Ang 2008; Assmus 2006; Assmus 2013; Bartunek 2012; Chen 2006; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hendrikx 2006; Hu 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Nasseri 2012; Patel 2005; Patila 2014; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Pokushalov 2010; Santoso 2014; Trifunovic 2015; Tse 2007; Turan 2011; Van Ramshorst 2009; Wang 2009; Wang 2010; Wang 2015; Yao 2008; Zhao 2008), and one trial isolated and concentrated the mononuclear cell fraction (Patel 2015). Three of these trials enriched the stem cell fraction in CD34‐positive haematopoietic progenitors by magnetic separation (Patel 2005; Wang 2009; Wang 2010), whilst one trial enriched the stem cell fraction in CD133‐positive cells (Nasseri 2012), and one trial in aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH)‐positive haematopoietic progenitors (Perin 2012b). Three trials cultured the mononuclear cell population from bone marrow ex vivo to enrich in mesenchymal progenitors (Chen 2006; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Mathiasen 2015), whereas one trial cultured mononuclear cells and enriched them in cardiopoietic cells by exposure to cardiopoietic factors (Bartunek 2012). In one three‐arm trial (Assmus 2006), bone marrow mononuclear cells were compared with circulating progenitor cells (CPCs), and with mononuclear cells isolated from venous peripheral blood. In the CPC arm, cells were isolated from peripheral blood by leukapheresis.

| Study ID | Co‐intervention | Intervention given by: | Route of cell administration | Intervention cell type | How are cells obtained? | What were they resuspended in? | Dose administered? | Comparator arm (placebo or control) |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IC or IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Autologous serum | IM: 84 (56) million cells IC: 115 (73) million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IC | BMMNC or CPC | BM aspiration (**) for BMMNC. Vein puncture, mononuclear cell isolation by gradient centrifugation and culture for 3 days for CPC | n/r | BMMNC: 205 (110) million cells CPC: 22 (11) million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Shockwave | Cardiologist | IC | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | X‐VIVO 10 medium and autologous serum | HDSW: 123 (69) million cells LDSW: 150 (77) million cells | Placebo (10 mL X‐VIVO 10 medium and autologous serum) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IC | BM‐MSC (cardiopoietic cells) | BM aspiration (**), culture for 6 days and exposure to cardiopoietic factors | Preservation solution (no details) | 733 (range 605 to 1168) million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IC | BM‐MSC | BM aspiration (**), culture for 7 days to select MSC | Heparinised saline | 5 million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IC | CPC | G‐CSF infusion for 4 days prior to vein puncture, mononuclear cell isolation by gradient centrifugation and culture for 3 days for CPC | Saline and 10% autologous serum | 69 (14) million cells | Placebo (cell‐free serum solution) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IC | BMMNC | G‐CSF infusion for 5 days and BM aspiration (**) | Autologous serum | n/r | Placebo (10 mL autologous serum) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | G‐CSF infusion for 5 days and BM aspiration (**) | Autologous serum | n/r | Placebo (2 mL autologous serum) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | n/r | n/r | Placebo (vehicle medium) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BM‐MSC | BM aspiration (**), culture to select MSC | n/r | n/r | Placebo (vehicle medium) | |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Heparinised saline | 60 (31) million cells | Placebo (heparinised saline) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IC | CPC | G‐CSF infusion for 5 days prior to vein puncture, mononuclear cell isolation by gradient centrifugation and culture for 4 days for CPC | n/r | 29 (12) million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IC | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Saline solution and 20% autologous serum | 132 (107) million cells | Placebo (8 mL saline; 2 mL autologous serum) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IM | CD133+ | G‐CSF infusion for 5 days prior to leukapheresis, mononuclear cell isolation by gradient centrifugation immunomagnetic selection to isolate CD133+ cells | Normal saline solution | 20 to 30 million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IM | CD34+ | G‐CSF infusion for 5 days prior to leukapheresis, mononuclear cell isolation by gradient centrifugation immunomagnetic selection to isolate CD34+ cells | Saline solution and 5% autologous serum | LD: 0.05 million cells MD: 0.1 million cells HD: 0.5 million cells | Placebo (0.9% sodium chloride; 5% autologous plasma) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IM | CD34+ | G‐CSF infusion for 5 days prior to leukapheresis, mononuclear cell isolation by gradient centrifugation immunomagnetic selection to isolate CD34+ cells | Saline solution and 5% autologous serum | LD: 0.1 million cells HD: 0.5 million cells | Placebo (0.9% sodium chloride; 5% autologous plasma) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BM‐MSC | BM aspiration (**), culture for 14 to 35 days to select MSC | Phosphate buffered saline with a drop of the participant’s blood | 77.5 (68) million cells | Placebo (phosphate buffered saline mixed with drop of participant’s blood) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IC | BMMNC | G‐CSF infusion for 5 days and BM aspiration (**) | Autologous serum | 86 (110) million cells | Placebo (10 mL autologous serum) | |

| G‐CSF | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | G‐CSF infusion for 5 days and BM aspiration (**) | Autologous serum | 52 (53) million cells | Placebo (2 mL autologous serum) | |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IM | CD133+ | BM aspiration (**), immunomagnetic selection to isolate CD133+ cells | Sodium chloride and 10% autologous serum | Median 5.1 million cells | Placebo (isotonic saline solution; 10% autologous serum) | |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IM | CD34+ | BM aspiration (**), immunomagnetic selection to isolate CD34+ cells | Heparinised saline and autologous serum | Median 22 million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IC | BMAC | BM aspiration (**) and concentration | Autologous serum | 3700 (900) million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Medium 199 containing albumin, heparin | Median 840 (range 52 to 135) million cells | Placebo (vehicle medium) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Saline containing 5% human serum albumin | 2 million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Saline containing 5% human serum albumin | 100 million cells | Placebo (cell‐free suspension in same volume) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | ALDH+ | BM aspiration (**) and cell sorting | Pharmaceutical grade human serum albumin | 2.4 (1.3) million cells | Placebo (5% pharmaceutical serum albumin) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Heparinised saline | 41 (16) million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Phosphate buffered saline with 10% autologous plasma | n/r | Placebo (phosphate buffered saline; 10% autologous plasma) | |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | n/r | 70.7 (32.4) million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Phosphate buffered saline with 10% autologous plasma | 15 million cells | Placebo (8 ‐ 12 x 0.1 mL phosphate buffered saline with 10% autologous serum) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IC | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | n/r | 99 (25) million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Phosphate buffered saline with 0.5% human serum albumin | 98 (6) million cells | Placebo (0.9% sodium chloride; 0.5% human serum albumin) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IC | CD34+ | BM aspiration (**), immunomagnetic selection to isolate CD34+ cells | Normal saline | Range 1.0 to 6.1 million cells | No additional therapy (control) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IC | CD34+ | BM aspiration (**), immunomagnetic selection to isolate CD34+ cells | Saline and human serum albumin | 56 (23) million cells | Placebo (saline; human serum albumin) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IM | CD133+ | n/r | n/r | n/r | Placebo (n/r) | |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Heparinised saline | 521 (44) million cells | Placebo (saline solution) | |

| Standard medical therapy | Cardiologist | IC | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Heparinised saline | 72 million cells | Placebo (0.9% sodium chloride containing heparin) | |

| CABG | Cardiothoracic surgeon | IM | BMMNC | BM aspiration (**) | Heparinised saline | 659 (512) million cells | Placebo (saline) |

**BM aspiration ‐ bone marrow aspiration and isolation of bone marrow mononuclear cells by gradient centrifugation.

ALDH: aldehyde dehydrogenase

BM: bone marrow

BMAC: bone marrow aspirate concentrate

BMMNC: bone marrow mononuclear cells

BM‐MSC: bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells

CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting

CPC: circulating progenitor cells

G‐CSF: granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor

HD: high dose

HDSW: high dose shockwave

IC: intracoronary

IM: intramyocardial

LD: low dose

LDSW: low dose shockwave

MD: medium dose

MSC: mesenchymal stem cells

n/r: not reported

SW: shockwave

In five trials, bone marrow stem cells were mobilised into circulation with granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor (G‐CSF) and subsequently isolated from blood via leukapheresis (Erbs 2005; Honold 2012; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011). Whilst previous trials reported severe but transient complications associated with G‐CSF treatment (Kang 2006), a recent pilot study demonstrated that G‐CSF can be safely administered to people suffering from IHD as none of the participants in this trial experienced the type of adverse events previously associated with G‐CSF treatment (Honold 2012). Two of these trials further enriched the stem cell population in CD34‐positive progenitors by magnetic separation (Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011). Four trials mobilised bone marrow cells into circulation with G‐CSF and isolated bone marrow mononuclear cells by density gradient centrifugation (Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM). Finally, one study administered CD133‐postive cells, but reported no details of cell isolation (Wang 2014).

All but six trials reported the mean (or median) dose of cells administered (Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Santoso 2014; Wang 2014). The mean dose of bone marrow mononuclear cells administered varied between 2 x 106 cells, in Perin 2011, and 8.4 x 108 cells, in Patila 2014, whilst bone marrow aspirate concentrate was administered at a mean dose of 3.7 x 109 cells (Patel 2015). Mesenchymal progenitor cells were administered at mean doses of between 5.0 x 106 cells, in Chen 2006, and 7.8 x 107 cells, in Mathiasen 2015, with one study administering 7.3 x 108 cardiopoietic cells (Bartunek 2012). Five studies that adminstered CD34‐positive cells gave mean doses of between 5.0 x 104 cells, in Losordo 2007, and 5.6 x 107 cells, in Wang 2010, and included two dose escalation studies comparing 5.0 x 104 cells, 1.0 x 105 cells, and 5.0 x 105 cells or 1.0 x 105 cells and 5.0 x 105 cells (Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011). CD133‐positive cells were administered at a median dose of 5.1 x 106 cells, in Nasseri 2012, or at doses of between 2 and 3 x 107 cells (Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011). The doses of ALDH‐positive cells averaged 2.96 x 106 cells (Perin 2012b). In the trial where bone marrow mononuclear cells were compared to CPCs, the mean dose of CPCs administered was between 2.9 x 106 cells, in Honold 2012, and 2.2 x 107 cells (Assmus 2006).

Thirteen trials administered the treatment via a coronary artery (intracoronarily (IC)) (Assmus 2006; Assmus 2013; Chen 2006; Erbs 2005; Hamshere 2015_IC; Honold 2012; Hu 2011; Mozid 2014_IC; Patel 2015; Turan 2011; Wang 2009; Wang 2010; Yao 2008), whilst 24 trials delivered the treatment intramyocardially (IM) (Bartunek 2012; Hamshere 2015_IM; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hendrikx 2006; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Mozid 2014_IM; Nasseri 2012; Patel 2005; Patila 2014; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Pokushalov 2010; Santoso 2014; Trifunovic 2015; Tse 2007; Van Ramshorst 2009; Wang 2014; Wang 2015; Zhao 2008). Of these 24 studies, 22 aided delivery of the treatment into the heart muscle using electromechanical mapping of the heart. The other two studies did not report whether the IM delivery of stem cells was aided in any other way (Hendrikx 2006; Zhao 2008). One trial included three treatment arms comparing IC and IM delivery of stem cells with control (Ang 2008).

Apart from G‐CSF, 17 studies administered co‐interventions. In nine studies, participants underwent coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) (Ang 2008; Hendrikx 2006; Hu 2011; Nasseri 2012; Patel 2005; Patila 2014; Trifunovic 2015; Wang 2015; Zhao 2008), and in seven studies, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was administered to all participants (Chen 2006; Erbs 2005; Turan 2011; Wang 2009), or to a subset of participants (Assmus 2006; Honold 2012; Yao 2008). One study administered shockwave targeted to the left ventricular anterior wall at either high or low dose (Assmus 2013).

Twenty‐five studies compared cell therapy with administration of a placebo consisting of a cell‐free solution, either a heparin saline solution or a saline solution containing the participant's own serum (Assmus 2013; Erbs 2005; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hendrikx 2006; Hu 2011; Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM; Nasseri 2012; Patila 2014; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Santoso 2014; Tse 2007; Van Ramshorst 2009; Wang 2010; Wang 2014; Wang 2015; Yao 2008; Zhao 2008); two further studies used a simulated mock injection procedure for participants in the control arm, but without administering a placebo solution (Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Perin 2011). The remaining 11 trials compared treatment to no treatment (Ang 2008; Assmus 2006; Bartunek 2012; Chen 2006; Honold 2012; Patel 2005; Patel 2015; Pokushalov 2010; Trifunovic 2015; Turan 2011; Wang 2009).

Three studies included multiple comparisons involving two or three intervention arms, including intracoronary versus intramyocardial cell administration (Ang 2008), mononuclear cells versus circulating progenitor cells (Assmus 2006), and high versus medium or low (Losordo 2007), or high versus low cell dose (Losordo 2011). We combined data for multiple intervention arms for the main analyses, although we used individual intervention trial arms for subgroup analyses where applicable. One three‐arm trial was also a cross‐over study (Assmus 2006); we have included only data up to the point of cross‐over (three months) in this review.

One study described aortic cross‐clamping during surgery with clamp times exceeding 25 to 30 minutes (Hendrikx 2006). Aortic cross‐clamping isolates the systemic circulation during surgery but causes ischaemia. Although increasing times of aortic cross‐clamping have been identified as a predictor of mortality, the effect of cross‐clamping in this study was not as strong as might be expected. This may be due to the fact that the cause of cardiac damage is multifactorial, including coronary lesions.

All but one study published only in abstract form reported the primary clinical outcome of mortality (Wang 2014). All but three studies reported periprocedural adverse events (or lack of) (Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Wang 2014), and a fourth study reported adverse events for shockwave treatment but not for cell therapy (Assmus 2013). See the Characteristics of included studies tables for details of the included studies; see Table 3 for a summary of the reporting of outcomes considered in this review.

| Study ID | Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| All‐cause mortality | Non‐fatal MI | Hospital readmission for HF | Composite MACEa | Arrhythmias | NYHA class | CCS class | Angina frequency | Exercise tolerance | Quality of life | LVEFb | ||||||||||||

| ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | ST | LT | |

| FR | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| FR | FR | NR | FR | FR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| PR* | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | NR | PR | PR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | PR | NR | FR | NR | |

| NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | FR | FR | |

| PR* | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | FR | FR | |

| PR* | PR* | PR* | FR | PR* | PR* | PR* | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | PR | |

| PR* | PR* | PR* | PR* | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | PR | |

| PR* | PR* | NR | PR* | NR | FR | PR* | FR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | FR | FR | NR | PR | |

| PR* | FR | NR | PR* | NR | PR* | PR* | FR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | FR | FR | NR | PR | |

| FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| PR* | FR | FR | FR | PR* | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | FR | FR | |

| FR | FR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | PR* | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | |

| FR | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | |

| PR* | PR* | PR* | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | |

| FR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | PR | FR | NR | FR | FR | FR | FR | NR | NR | |

| FR | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | FR | NR | |

| FR | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| FR | NR | PR* | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | PR | NR | FR | NR | |

| PR* | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | PR | |

| NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | PR | PR | |

| NR | PR* | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | FR | |

| PR* | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | |

| FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| PR* | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | PR* | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | FR | |

| PR* | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | FR | FR | |

| PR* | FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| PR* | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | FR | |

| FR | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | FR | |

| PR* | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| PR* | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| PR* | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PR | NR | |

| FR | NR | PR* | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | FR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | FR | NR | |

| Total (%) analysedc | 1637 (85.8) | 1010 (53.0) | 881 (46.2) | 461 (24.2) | 482 (25.3) | 495 (26.0) | 288 (15.1) | 201 (10.5) | 959 (50.3) | 363 (19.0) | 741 (38.9) | 346 (18.1) | 608 (31.9) | 142 (7.4) | 428 (22.4) | 82 (4.3)d | 535 (28.1) | 227 (11.9) | 197 (10.3)e | 151 (7.9)e | 439 (23.0)f | 110 (5.8)f |

CCS: Canadian Cardiovascular Society; FR: full reporting, outcome included in analysis; HF: heart failure; LT: long‐term follow‐up (≥ 12 months); LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE: major adverse clinical events; MI: myocardial infarction; NR: outcome not reported; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PR: partial reporting with insufficient information on outcome reported for inclusion in analysis; PR*: no incidence of outcome observed; ST: short‐term follow‐up (< 12 months)

aComposite measure of mortality, reinfarction, or rehospitalisation for heart failure.

bLVEF measured by any method.

cTotal number of participants included in meta‐analysis of outcome (% of total number of participants from all included studies).

dNo meta‐analysis was performed, as only one study reported values suitable for inclusion.

eMinnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire.

fTotal number analysed given for LVEF measured by magnetic resonance imaging.

Studies awaiting classification

Ten independent studies (12 references) met the eligibility criteria for this review but reported insufficient data for inclusion; these studies are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Ongoing studies

We identified 28 ongoing trials described in five references and 31 ongoing trial records; see Characteristics of ongoing studies for details.

Excluded studies

We excluded 54 studies (described by 70 references and 15 ongoing trial records) from the review following full‐text assessment against the eligibility criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies tables). In summary, we excluded studies for the following sequential reasons: 10 studies were of people with acute myocardial infarction (AMI); 16 studies were single‐arm trials; seven studies compared multiple interventions but with no control or placebo arm; eight studies did not randomise participants to treatment arm; two studies administered G‐CSF to the intervention arm but not the comparator group; one study measured outcomes not relevant to this review; six studies were terminated or withdrawn; one study included non‐bone marrow‐derived cells; one study compared allogeneic cells with a control group; one study was a literature review; and one study was performed in animals.

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the risk of bias in individual studies is given below and in Figure 2. Further details of our assessment of risk of bias can been found in the Characteristics of included studies tables. We considered only five trials to have a low risk of bias across all domains (Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Van Ramshorst 2009).

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Twenty‐seven studies provided details of randomisation methods with a low risk of bias from random sequence generation. These methods included sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes (Hendrikx 2006; Patila 2014; Van Ramshorst 2009), simple randomisation table (Santoso 2014; Tse 2007), or randomisation codes generated electronically (Assmus 2006; Assmus 2013; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hu 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM; Patel 2015; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Pokushalov 2010; Zhao 2008), by a study statistician (Losordo 2007; Perin 2011), by picking a coloured ball (Patel 2005), or via a centralised site‐independent process (Bartunek 2012; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2011; Nasseri 2012). Of these, 15 studies described appropriate methods of allocation concealment with a low risk of bias (Assmus 2013; Bartunek 2012; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hendrikx 2006; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Nasseri 2012; Patila 2014; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Santoso 2014; Tse 2007; Van Ramshorst 2009), whilst in 12 studies allocation concealment was unclear (Assmus 2006; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Hu 2011; Losordo 2007; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM; Patel 2005; Patel 2015; Perin 2012b; Pokushalov 2010; Zhao 2008).

We found five trials in which no description was given as to what methods were used to generate the random sequence to be at unclear risk of selection bias (Ang 2008; Erbs 2005; Honold 2012; Trifunovic 2015; Turan 2011). The method of generation of randomisation sequence was also not reported in six Chinese trials, which we deemed to have a high risk of bias (Chen 2006; Wang 2009; Wang 2010; Wang 2014; Wang 2015; Yao 2008).

Blinding

In 24 studies, participants randomised to the control group received a placebo injection (Assmus 2013; Erbs 2005; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hendrikx 2006; Hu 2011; Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM; Nasseri 2012; Patila 2014; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Santoso 2014; Tse 2007; Van Ramshorst 2009; Wang 2010; Wang 2015; Yao 2008; Zhao 2008), with all but one study reporting that the control group underwent bone marrow aspiration (Mathiasen 2015); we judged these trials to be at a low risk of performance bias. We deemed two additional trials to have a low risk of performance bias, as although no placebo was administered, participants in the control group underwent a sham procedure (Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Perin 2011).

We considered nine trials in which no placebo was administered to have a high risk of performance bias (Ang 2008; Assmus 2006; Bartunek 2012; Chen 2006; Honold 2012; Patel 2015; Pokushalov 2010; Trifunovic 2015; Turan 2011). Two trials were reported as "double‐blind" (Wang 2014), or as having blinded participants (Patel 2005), but no details of a placebo were given; a third trial reported no details of blinding (Wang 2009). We judged the risk of performance bias in these trials to be unclear.

We assessed two trials as having a high risk of detection bias: one was reported as an "open‐label" trial with no details of blinding given (Trifunovic 2015), and one trial reported that outcome assessors were not blinded (Wang 2009). We judged two trials in which which blinding of outcome assessors was not reported as at unclear risk of detection bias (Chen 2006; Wang 2014). All other trials reported the blinding of outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data

One trial had a high risk of attrition bias (Bartunek 2012): 11 participants randomised to the cell therapy group were excluded from the analyses as they did not receive the study intervention. In the study report, these participants were analysed as part of the control group (although in this review they have been excluded). The risk of attrition bias was unclear in four studies in which some participants were excluded from the analyses without sufficient explanation (Ang 2008; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Honold 2012). We also attributed an unclear risk of attrition bias to one study reported in abstract form only (Wang 2014). In all other trials, any withdrawals or losses to follow‐up were similar in both treatment arms with reasons for withdrawals fully documented.

Selective reporting

We attributed a high risk of reporting bias to one study in which results have only been published as a conference abstract (Wang 2014). Twenty‐two trials were prospectively registered on a clinical trial database. Of these, 13 studies reported all outcomes described in the the trial protocol, with a low risk of reporting bias (Ang 2008; Assmus 2006; Assmus 2013; Hu 2011; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Nasseri 2012; Patel 2015; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Van Ramshorst 2009), whilst in seven studies, we observed some differences between outcomes described in the study protocol and those reported. Specifically, three studies reported results for additional outcomes (Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Santoso 2014); two studies were a pilot study report of secondary outcomes only (Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM); one study failed to report six‐month results as described in the protocol (Patila 2014); and in one study, different definitions of primary and secondary outcomes were reported in the study protocol and the publication of results (Bartunek 2012). We deemed the risk of reporting bias in these seven studies to be unclear. For two trials reported in abstract form only (Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM), we requested and obtained data for all outcomes presented in the trial protocol from the authors, therefore we judged these trials to be at low risk of reporting bias.

We identified no prospectively registered trial protocol for the remaining 15 trials, and although the results of all outcomes described in the methods were reported, we judged the risk of reporting bias to be unclear.

We identified no obvious asymmetry from a funnel plot for mortality (Figure 3). In a regression test for asymmetry (Egger's test), the model intercept was ‐0.02 (P = 0.90) at short‐term follow‐up and ‐0.004 (P = 0.98) at long‐term follow‐up, with no evidence of publication bias. However, of 28 identified ongoing trials, 11 trials (787 participants) were recorded as having been completed or were due to have been completed in advance of our search date, but we identified no publications for them and no study results were posted on the trial database. We therefore cannot rule out the possibility of publication bias.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Stem cells versus no stem cells, outcome: 1.1 Mortality.

Other potential sources of bias

Twenty‐eight studies reported details of study funding or sponsorship (Ang 2008; Assmus 2006; Assmus 2013; Bartunek 2012; Erbs 2005; Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Hu 2011; Jimenez‐Quevedo 2011; Losordo 2007; Losordo 2011; Mathiasen 2015; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM; Nasseri 2012; Patel 2015; Patila 2014; Perin 2011; Perin 2012a; Perin 2012b; Santoso 2014; Tse 2007; Van Ramshorst 2009; Wang 2015; Yao 2008; Zhao 2008. The majority of these studies were funded entirely by academic or healthcare research grants, or both and received no commercial sponsorship. Four studies acknowledged provision of equipment (Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC; Losordo 2007; Perin 2012a), and two studies acknowledged receipt of consultant fees, from Biosense Webster, in Tse 2007, and Cook Medical (Patel 2015). Four studies declared full commercial sponsorship: from Aldagen (Perin 2012b), Baxter Healthcare (Losordo 2011), Cardio3 BioSciences (Bartunek 2012), and Harvest Technologies (Patel 2015), and nine studies declared partial commercial funding: from Baxter Healthcare (Losordo 2007), Chugai Pharma UK and the Cordis Corporation (Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM), Miltenyi Biotec (Nasseri 2012), and BioCardia (Heldman 2014_BMMNC; Heldman 2014_BM‐MSC), and an unrestricted grant from t2cure GmbH (Assmus 2013). We judged all 13 studies that received some degree of commercial funding to be at high risk of bias. The primary investigator in four included trials is also an author of this review (Hamshere 2015_IC; Hamshere 2015_IM; Mozid 2014_IC; Mozid 2014_IM).

Effects of interventions

An overview of results for the primary outcomes of mortality and periprocedural adverse events, and for morbidity outcomes (non‐fatal MI, rehospitalisation for HF, arrhythmias, composite major adverse clinical events) and LVEF measured by MRI is given in summary of findings Table for the main comparison. We excluded quality of life and performance status outcomes since different measures are likely to be used for different participant diagnoses, and therefore fewer trials are likely to have reported each of these outcomes.

In one study (Yao 2008), continuous measures were reported as mean +/‐ standard deviation. However, visual inspection of the data revealed that the standard deviations were considerably lower than might be expected for all continuous outcomes. This study also reported P values for statistical comparisons between the baseline and follow‐up data using paired t‐tests. However, we could not identify the reported significance values, either using the standard deviations provided, or based on an assumption that the values were in fact standard errors. We therefore could not verify or include continuous data from this study.

Primary outcomes

Mortality

All but one study included mortality as an outcome (Wang 2014), which was published in abstract form only (see Table 3; Table 4).

| Study ID | Number of analysed participants | All‐cause mortality events | Non‐fatal MI events | Hospital readmission for HF | Composite MACEa | Arrhythmia events | |||||||||||

| Cells | No cells | Cells | No cells | Length of follow‐up | Cells | No cells | Length of follow‐up | Cells | No cells | Length of follow‐up | Cells | No cells | Length of follow‐up | Cells | No cells | Length of follow‐up | |

| 42 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 6 mthsa | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 52 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 3 mths | 1 | 0 | 3 mths | 1 | 1 | 3 mths | 1 | 1 | 3 mths | 0 | 1 | 3 mths | |

| 43 | 39 | 6 | 8 | 45.7 (17) mths | 1 | 4 | 45.7 (17) mths | 8 | 13 | 45.7 (17) mths | 14 | 19 | 45.7 (17) mths | 6 | 13 | 45.7 (17) mths | |

| 21 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 24 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | 6 | 4 | 24 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 22 | 23 | 2 | 4 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 13 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 15 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 1 | 0 | 12 mths | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 1 | 0 | 12 mths | 1 | 1 | 12 mths | |

| 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 1 | 1 | 12 mths | 1 | 1 | 12 mths | 0 | 1 | 12 mths | |

| 19 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 0 | 1 | 12 mths | 0 | 1 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 19 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 12 mths | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 1 | 1 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 11 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 4 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 23 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 60 mths | 1 | 2 | 60 mths | 0 | 2 | 60 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 31 | 29 | 1 | 2 | 12 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | 3 | 4 | 6 mths | 1 | 0 | 12 mths | |

| 19 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 1 | 1 | 6 mths | |

| 18 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 1 | 12 mths | |

| 112 | 56 | 0 | 3 | 12 mths | 6 | 7 | 12 mths | 3 | 4 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 40 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 6 | 2 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | 3 | 1 | 6 mths | |

| 14 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 1 | 0 | 6 mths | 1 | 1 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 10 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 0 | 3 | 6 mths | 2 | 2 | 6 mths | |

| 30 | 30 | 1 | 3 | 34 mthsb | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 25 | 25 | 3 | 10 | 10 yrs | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 22 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | 2 | 0 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | |

| 13c | 17c | 0 | 0 | Median 60 mths | 0 | 0 | Median 60 mths | 1 | 1 | Median 60 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 20 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 61 | 31 | 1 | 0 | 6 mths | 1 | 0 | 6 mths | 3 | 5 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 1 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 3 | 2 | 6 mths | |

| 55 | 54 | 6 | 21 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | |

| 19 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 23 (8) mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 1 | 1 | 6 mths | |

| 15 | 15 | 2 | 4 | Median 5 yrs | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 19 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 19 (9) mths | 0 | 1 | 3 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 38 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 12 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 25 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 56 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 1 | 6 mthsd | |

| n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 45 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | |

| 24 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | 0 | 1 | 6 mths | 1 | 2 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | |

| 18 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 6 mths | 0 | 0 | 6 mths | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | n/r | 1 | 0 | 6 mths | |

HF: heart failure; MACE: major adverse clinical events; MI: myocardial infarction; n/r: not reported

aAng 2008: participants followed up for six months; mortality reported as “death within 30 days of treatment”.

bNasseri 2012: deaths reported “beyond follow‐up period” occurred at 31 and 34 months.

cPatila 2014: mortality rates reported in 20/19 participants at 12 months and 13/17 participants at 60 months.

dWang 2010: values are for ventricular arrhythmia (atrial arrhythmia also reported but unclear whether any participant overlap).