Methotrexate for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled. Duration of treatment and study was 9 months. N=67. Prepackaged coded sets (equal number of methotrextae or placebo tablets) were delivered to each centre. If all of these were used up subsequent randomization was performed by a central pharmacy | |

| Participants | Patients with definite, chronic active ulcerative colitis (Mayo clinic score of > or = 7 at entry). Chronicity was defined as steroid therapy at > or = 7.5 mg/day for at least 4 months of the proceeding year. Ulcerative colitis was diagnosed by clinical, radiographic, endoscopic, and pathological criteria. | |

| Interventions | Oral methotrexate (n=30; 12.5 mg/wk ‐ 2.5 mg/day) or identical placebo (n=37) for 9 months | |

| Outcomes | Remission: a Mayo clinic score of < or = 3 (or Mayo score of < or = 2 without sigmoidoscopy results) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Not a RCT ‐ open label clinical trial | |

| Not a RCT ‐ retrospective chart review | |

| No placebo or active comparator ‐ trial compared two doses of subcutaneous methotrexate (15 mg/week versus 25 mg/week) | |

| Not a RCT ‐ case series | |

| Not a RCT ‐ retrospective chart review looking at maintenance treatment with methotrexate | |

| Not a RCT ‐ open label clinical trial | |

| Not a RCT ‐ retrospective chart review | |

| Not a RCT ‐ case control study of pharmacogenetics of methotrexate therapy in IBD | |

| Not a RCT ‐ case series | |

| Not a RCT ‐ open label clinical trial | |

| Not a RCT ‐ retrospective chart review | |

| Allocation concealment was unclear | |

| Not a RCT ‐ open label clinical trial | |

| Not a RCT ‐ case series | |

| Not a RCT ‐ retrospective chart review | |

| Not a RCT ‐ retrospective chart review |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | A controlled, randomized, double‐blind, multicenter study, comparing methotrexate versus placebo in the remission of steroid‐refractory ulcerative colitis |

| Methods | |

| Participants | Steroid‐dependent ulcerative colitis (n=110) |

| Interventions | Methotrexate (n=55) or placebo (n=55) given once weekly by intramuscular injection |

| Outcomes | Remission without steroids at week 16 |

| Starting date | June 1, 2007 |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

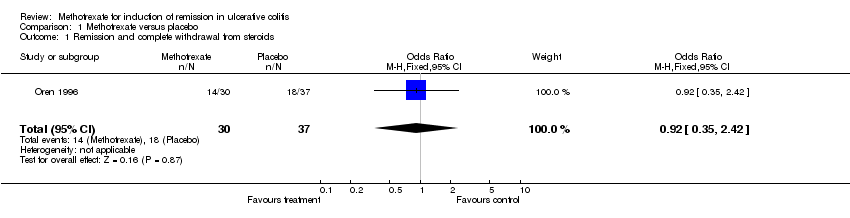

| 1 Remission and complete withdrawal from steroids Show forest plot | 1 | 67 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.35, 2.42] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Methotrexate versus placebo, Outcome 1 Remission and complete withdrawal from steroids. | ||||

Comparison 1 Methotrexate versus placebo, Outcome 1 Remission and complete withdrawal from steroids.

| Study ID | Description | Results |

| Baron 1993 | Open label clinical trial enrolling patients with steroid dependent or steroid refractory IBD (Crohn's n=10, UC n=8). Patients received oral Mtx 15 mg/wk and prednisone. The primary outcomes were complete or partial withdrawal from steroids and mean steroid use. | UC patients: mean prednisone dose dropped from 26.3 +/‐ 3.2 mg/day to 12.7 +/‐ 2.0 mg/day (P < 0.001). Three patients had a partial response. Adverse events were mild. |

| Cummings 2005 | Retrospective chart review at two hospitals. Steroid dependent or steroid refractory UC patients (n=50) were treated with oral Mtx (mean dose 19.9 mg/wk for a median of 30 weeks). The primary outcome was remission defined as lack of treatment with steroids for 3 months or more. The secondary outcome was response defined as good, partial or nil, proportionate reduction of steroids. | Remission occurred in 42% of patients. The reponse was good in 54% and partial in 18%. Adverse events occurred in 23%; 10% stopped treatment due to adverse events. |

| Egan 1999 | Randomized, single‐blind trial comparing two doses of subcutaneous Mtx (15 mg/wk, n=18, versus 25 mg/wk, n=14) in patients with steroid dependent or refractory IBD. The primary outcome was remission at 16 weeks defined as the presense of quiescent disease (IBDQ score > or = 170) and discontinuation of prednisone. The secondary outcome was partial response defined as ability to discontinue prednisone without a decrease in IBDQ or a clinically significant improvement in disease activity. | After 16 weeks 17% (3/18) of patients in the 15 mg group acheived remission compared to 17% (2/12) of patients in the 25 mg group (P = N.S.). Improvement occurred in 39% (7/18) of the 15 mg group compared to 33% (4/12) of the 25 mg group (P = N.S.). Adverse events occurred in 11% (2/18) of patients in the 15 mg group compared to 17% (2/12) of patients in the 25 mg group (P = N.S.). |

| Egan 2000 | Case series. Three patients with steroid refractory UC and 2 patients with steroid refractory Crohn's disease who failed monotherapy with subcutaneous methotrexate 25 mg/week for 16 weeks were treated with the combination of methotrexate and low‐dose oral cyclosporine (3 mg/kg/day) for an additional 16 weeks. The primary outcome was remission at 16 weeks defined as the presense of quiescent disease (IBDQ score > or = 170) and discontinuation of prednisone. The secondary outcome was partial response defined as ability to discontinue prednisone without a decrease in IBDQ or a clinically significant improvement in disease activity. | The three patients with UC experienced clinical improvement with a mean increase in IBDQ score from 164 to 190 points (P = 0.01). One patient developed hypertension. |

| Fraser 2002 | Retrospective chart review at two hospitals. Seventy patients were reviewed (Crohn's n=48, UC n=22). Patients were treated with oral Mtx (n=62) or IM Mtx (n=8) at a mean dose of 20 mg/week for a mean duration of 17.1 months. Remission was defined as the lack of a need for oral steroids (either prednisolone or budesonide) for at least 3 months. Patients who were well on low doses of prednisolone or budesonide steroids were recorded as ‘remission not achieved’. The continued use of oral 5‐aminosalicylic acid compounds and steroids or 5‐aminosalicylic acid enemas was allowed within the definition of remission. Relapse was defined as the need for re‐introduction of steroids, the need for a surgical procedure or the use of infliximab. | Remission was achieved in 34 of 55 (62%) of patients who completed more than 3 months of treatment. Life‐table analysis showed that the chances of remaining in remission at 12, 24 and 36 months, if treatment was continued, were 90%, 73% and 51% respectively. The chances of remaining in remission after stopping treatment at 6, 12 and 18 months were 42%, 21% and 16% respectively. |

| Fraser 2003 | Open label clinical trial. Eight patients with chronically active moderate to severe UC refractory to corticosteroids and azathioprine/6‐MP were treated with 25 mg/week IM Mtx (and folic acid) for 16 weeks. Efficacy was assessed with the Mayo clinic score. | Six of eight patients completed 16 weeks of treatment. One patient withdrew due to severe exacerbation and one withdrew due to failure to improve. Two patients developed anemia and one patient developed hypertransaminasemia. The median Mayo clinic score at 16 weeks was 8 (range 6 to 11). Two patients were referred for colectomy at the end of the study. |

| Gibson 2006 | Retrospective chart review at a single IBD clinic. Sixty five patients (Crohn's n=45, UC n=20) were reviewed. The initial weekly dose was 25 mg in 29 patients, 20 mg in 16 patients, 15 mg in 7 patients or 10 mg in 3. Eighty‐four percent received Mtx by subsutaneous injection. All patients received folate supplementation. Response was defined as improvement in bowel symptoms and/or ability to reduce the dose of steroids. Remission was defined as improvement in symptoms with no requirement for steroids for 3 months, or ability to wean off steroids. | Remission was achieved by 12 of 19 (63%) patients wiuth UC. An additional patient with UC had a response to treatment. The median duration of treatment was 11 months (range 3 to 36) in responders and 6 months (range 1.5 to 10) in non‐responders. Fifteen per cent of patients experienced adverse events. |

| Herrlinger 2005 | Case control study of pharmacogenetics of Mtx therapy in IBD. Allele frequencies in the disease and healthy populations were assessed in 102 IBD patients treated with Mtx, 202 patients with Crohn's disease, 205 patients with UC and 189 healthy volunteers. All subjects were genotyped for four polymorphisms. | No significant difference in the allele frequencies between Crohn's disease, UC and healthy were detected. Twenty‐one per cent of Mtx treated patients experienced adverse events. |

| Houben 1994 | Case series. Fifteen IBD patients (Crohn's disease n=13, UC n=2) were treated with IM Mtx 25 mg/week for 12 weeks, followed by a tapering oral dose. One patient was treated twice. Disease activity was determined after 1, 2 and 3 months of treatment. | The mean defecation frequency went down from 7 to 2 times daily after 12 weeks and prednisone dose could be lowered from 22 mg to 15 mg after 3 months. Subjective and objective improvement was noted in 12/15 patients. No serious adverse events were reported. |

| Kozarek 1989 | Open label clinical trial. Twenty‐one patients with refractory IBD (Crohn's n=14, UC n=7) received 25 mg/week IM Mtx for 12 weeks. After 12 weeks, patients were switched to a tapering oral dose if clinical and objective improvement was noted. | Five of 7 UC patients had an objective response as measured by the Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (13.3 to 6.3, P=0.007). Prednisone dosage decreased from 38.6 mg +/‐ 6.35 (SEM) to 12.9 mg +/‐ 3.4, P=0.01. Five of 7 had histological improvement. None of the UC patients had normal flexible sigmoidscopy results. Adverse events included mild rises in transaminase levels in 2 patients, transient leukopenia in 1, self‐limited diarrhea and nausea in 2 patients, brittle nails (1 case) and atypical pneumonitis (1 case). |

| Kozarek 1992 | Retrospective chart review. Over a 4 year period (1987 to 1991) 86 patients with refractory IBD (Crohn's n=37, UC n=30) were started on 25 mg/week parenteral Mtx. Those patients who responded clinically at 12 weeks were offered weekly oral Mtx therapy (7.5 to 15 mg). Outcomes included the DAI (scored 0 to 15), prednisone dose, and Mtx toxicity. | Seventy per cent of UC patients had a symptomatic and objective response. At a mean follow‐up of 59 weeks, only 40% of UC patients continued to respond to Mtx (DAI 5.0 +/‐ 0.9; prednisone 12 +/‐ 3.9 mg), 15 of 30 UC patients required colectomy and one patient stopped Mtx due to hypersenitivity pneumonitis. |

| Mate‐Jimenez 2000 | Randomized controlled trial. Blinding not used and allocation concealment was not clear. Seventy‐two steroid‐dependent IBD patients (UC n=34, Crohn's n=38) receiving treatment with prednisone were randomly assigned to receive, orally, over a period of 30 weeks 1.5 mg/kg/day of 6‐MP or 15 mg/week of MTX or 3 g/day of 5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA). For UC patients remission was defined as stopping prednisone and a Mayo clinic score of < 7. | Remission rates at 30 weeks were 78.6%, 58.3% and 25% in the 6‐MP, Mtx and 5‐ASA groups respectively (P <0.05 for the 6‐MP versus 5‐ASA comparison). |

| Paoluzi 2002 | Open label clinical trial. Forty‐two patients with steroid dependent or steroid resistant active UC were treated with a daily dose of azathioprine (2 mg/kg) and, if intolerant or not responding, with methotrexate (12.5 mg/week IM). Efficacy was assessed by clinical, endoscopic and histological examinations at 6 months. Patients achieving clinical remission continued with treatment and were followed up. Ten patients received Mtx. The achievement of complete remission with the ability to discontinue oral steroids was defined as the primary end‐point of efficacy. Response to treatment was defined as follows: complete remission equals achievement of clinical, endoscopic and histological remission; improvement equals disappearance of symptoms (clinical remission) with endoscopic and histological improvement of inflammatory changes; failure equals worsening, no benefit or clinical improvement with the persistence of unmodified inflammatory changes of the mucosa. | Mtx induced complete remission in six patients (60%) and improvement in four (40%). During follow‐up, a larger number of patients on azathioprine relapsed in comparison with patients on methotrexate [16/28 (57%) vs. 2/10 (20%), respectively; P < 0.05]. |

| Siveke 2003 | Case series. Three patients with steroid dependent or steroid resistant UC were treated with 25 mg/week IM Mtx. These patients received 10 mg of folate orally on the day after injection. An additional patient received 15 mg of methotrexate, with the dose being adjusted to 25 mg following increased activity of colitis. | Three of 4 patients achieved remission. One patient had to discontinue Mtx due to an increase in aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase levels despite dose reduction and prophylactic supplementation of folate. |

| Soon 2004 | Retrospective chart review. Seventy‐two patients (Crohn's n=66, UC n=6) were treated with mean dose of 18.2 mg/week of Mtx for six months. Mtx was given orally in 64 patients and intramuscularly in eight patients. Clinical response was defined as sustained withdrawal of oral steroids within 3 months of starting treatment and sustained for a futher 3 months or fistula improvement. New episodes of steroid therapy, infliximab or surgery during the first 6 months were considered as failure to achieve clinical response. | Fifty‐four patients completed six months of treatment. Clinical response was achieved in 22 (40.7%) patients [19 of 48 (39.6%) with CD and three of six (50%) with UC]. |

| Te 2000 | Retrospective chart review looking at hepatotoxicity among IBD patients who had received a mnimum cumulative dose of 1500 mg of Mtx | In 20 patients who had liver biopsies, the mean cumulative methotrexate dose was 2633 mg (range, 1500–5410 mg), given for a mean of 131.7 wk (range, 66–281 wk). Nineteen of 20 patients (95%) had mild histological abnormalities (Roenigk’s grade I and II), and one patient had hepatic fibrosis (Roenigk’s grade IIIB). |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Remission and complete withdrawal from steroids Show forest plot | 1 | 67 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.35, 2.42] |