Terapia cognitivoconductual para el tinnitus

Referencias

Referencias de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios excluidos de esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios en curso

Referencias adicionales

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 23 (of 37 initially recruited) participants (12 male), mean age 70.1 years (range 65 to 79), allocated to 2 groups: CBT (12 patients) and waiting list control (11 patients) Inclusion criteria were: Exclusion criteria were: | |

| Interventions | Two groups: | |

| Outcomes | Four outcome measures: Comparisons were made at pre‐ and post‐treatment points. Also at 3 months follow up the outcomes were compared, but at this point the data were non‐experimental, as the waiting list group had also received CBT after the post‐treatment observations. | |

| Notes | There were no drop‐outs. Outcomes were measured pre‐ and post‐treatment (6 weeks), then the waiting list group received the same treatment, so follow‐up results at 3 months cannot be used. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 60 (of 65 initially recruited) patients (52 male, mean age 64 years) allocated to 3 groups: 20 patients in each group Inclusion criteria were: | |

| Interventions | Three experimental conditions: | |

| Outcomes | Self‐report questionnaires administered at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 12 months follow up: TRQ, THQ, TEQ, TCQ, TCSQ, TKQ, BDI, LCB and a Self‐Monitoring of Tinnitus record, including: loudness, notice and bother by tinnitus | |

| Notes | The number of patients that were lost to the 12‐month follow up was 13 (4 in the 'cognitive education', 3 in the education alone and 6 in the waiting list group). Total drop‐out at 12‐month follow up = 13/60 = 21.66%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 72 (of initially 101 recruited) participants allocated into 2 groups: treatment group (50% female, mean age 45.9 years) and waiting list group (47% female, mean age 48.5 years) Inclusion criteria were: (1) Medical examination by ENT specialist or an audiological physician | |

| Interventions | Two groups: | |

| Outcomes | Self‐report questionnaires administered at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 12 months follow up: TRQ, THI, HADS, ISI and a daily diary recording of tinnitus on visual analogue scales, including loudness, distress and perceived stress during the day | |

| Notes | Total drop‐out at 12‐month follow up = 12%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Randomisation by coin tossing |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation by drawing code numbers from a basket with the total sample. | |

| Participants | 43 (of 52 initially recruited) patients (60.5% male, mean age 48 years) allocated to 4 groups Inclusion criteria were: | |

| Interventions | Four experimental groups: Each treatment group (TCT1, TCT2, yoga) consisted of 10 2‐hourly sessions; each group was conducted by a different qualified professional | |

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included: All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 3 months follow up (the latter one except for audiological outcomes) | |

| Notes | The number of patients that were lost was 9 (3 in TCT1, 2 in TCT2t, 1 in yoga and 3 in the WLC). Total drop‐out = 9/43 = 20.93%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Randomisation by drawing code numbers from a basket with the total sample |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation by drawing code numbers from the total sample and the sequential assignment to the treatment conditions until a pre‐set number of subjects was reached. | |

| Participants | 95 (of 116 initially recruited) patients (51.6% female, mean age 46.8 years) allocated to 4 groups Inclusion criteria were: Exclusion criteria were: | |

| Interventions | Four experimental groups: TCT comprised 11 sessions of 90 to 120 minutes duration, each group consisted of 6 to 8 patients and was conducted by 2 qualified psychologists All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment 6 and 12 months follow up | |

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included: | |

| Notes | The number of patients lost was 21 (13 in the TCT group, 4 in MC‐E and MC‐R each). Total drop‐out = 21/95 = 22.1%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation by a list of random sequence. | |

| Participants | 43 (of 48 initially recruited) patients (46.75% female, mean age 46.75 years) allocated to 2 groups Inclusion criteria were: | |

| Interventions | Two experimental groups: The psychophysiologically‐oriented intervention comprised 9 sessions of 60 minutes duration conducted by 5 supervised graduate student psychologists All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment (8 weeks) and 6 months follow up | |

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included: All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 6 months follow up | |

| Notes | The number of patients that were lost at the post‐treatment point was 1 (in the intervention group) and 1 more drop‐out (in the control group) occurred at the first follow‐up point. Total drop‐out = 2/43 = 4.65%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 111 (of 130 initially recruited) patients allocated to 2 groups: treatment group (44.2% female, mean age 49.46 years) and waiting list group (44.1% female, mean age 52.93 years) Inclusion criteria were: Exclusion criteria were: | |

| Interventions | Two experimental groups: The biofeedback‐based behavioural intervention consisted of 12 individual therapy sessions of 60 minutes duration conducted by 4 trained therapists. Each session contained biofeedback as well as CBT elements following a structured manual. | |

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included: All assessments were completed at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment and 6 months follow up | |

| Notes | Total drop‐out at post‐treatment measurement = 19/130 = 14.61%. Results for the adverse effects subscale (M = 1.51; SD = 0.63; range 1 to 6) indicated that the majority of the patients did not experience negative side effects caused by the treatment. Results for the satisfaction with therapy subscale (M = 5.16, SD = 0.51; range 1 to 6) indicated that patients were quite content with the treatment. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Randomisation using a computer‐generated random list |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation by throwing dice. | |

| Participants | 77 (of 83 initially recruited) patients (66.6% male, mean age 53.8 years) allocated to 3 groups Inclusion criteria were: | |

| Interventions | Three experimental groups: TCT comprised 11 sessions of 90 to 120 minutes duration, each group consisted of 6 to 8 patients. There was a 4‐week recess between the first and second session of TCT and HT to assess the effect of education alone, and then TCT and HT continued. HT was conducted in 5 sessions of 90 to 120 minutes (spaced over 6 months) to a group of 6 to 8 patients, where education, noise generator and counselling was conducted. Education consisted in a single session informing about the physiology and psychology of tinnitus. This session was identical to the first session for TCT and very similar to the HT one. Patients in EDU group were also offered a further treatment after 15 weeks should they wish. Assessments were carried out at 7 measurement periods: at pre‐treatment, post‐treatment, 6, 12 and 18 (21 for TCT) months follow up | |

| Outcomes | The outcome measures included: Most variables were assessed at pre‐ and post‐treatment periods; the TQ was the only one applied at every time period Objective tinnitus parameters (pitch masking and masking measurements) were excluded from the study | |

| Notes | The number of patients that were lost before the post‐treatment period was 6 (2 in the TCT group, 1 in HT group and 3 in EDU group). A further 2 drop‐outs (one in TCT and one in HT group) occurred at 18 months follow up (21 months for the TCT group). Total drop‐out = 8/77 = 10.38%. There were no adverse effects reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Randomisation by throwing dice |

ATQ = Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; DB = double‐blind; IDCL = International Diagnostic Check‐List; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; JQ = Jastreboff Questionnaire; LCB = Locus of Control of Behavior Scale; QCC = Questionnaire of Catastrophizing Cognitions; QDC = Questionnaire of Dysfunctional Cognitions; QS = quality score; R = randomisation; SCL‐90R = Symptom Checklist; SSR = Questionnaire of Subjective Success; STI = Structured Tinnitus Review; TCQ = Tinnitus Cognitions Questionnaire; TCSQ = Tinnitus Coping Strategies Questionnaire; TDQ = Tinnitus Disability Questionnaire; TEQ = Tinnitus Effect Questionnaire; THI = Tinnitus Handicap Inventory; THQ = Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire; TKQ = Tinnitus Knowledge Questionnaire; TQ = Tinnitus Questionnaire; TRCS = Tinnitus Related Control Scale; TRQ = Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire; TRSS = Tinnitus‐related Self‐Statement Scale; W = withdrawals

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (50%) | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (51% in the CBT group) | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (43.33%) | |

| ALLOCATION: Not randomised | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTION: Not CBT | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTION: CBT OUTCOME: No usable data. No primary outcome | |

| ALLOCATION: Inadequate randomisation, as patients with severe tinnitus (Tinnitus Questionnaire score > 40) were allocated to CBT and those with lower scores to the Tinnitus Education group. The randomisation was then done for receiving (or not) noise generators. | |

| ALLOCATION: Not randomised | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (44.8%) | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTION: Internet CBT versus CBT. Not an appropriate comparison for this review. | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (39.53%) | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTION: Cognitive behavioural tinnitus coping training (TCT) versus Habituation‐based Training (HT) OUTCOME: This study looks at possible predictor factors in the participants from another already published 3‐arm trial (Zachriat 2004) which was already included in this review. Not an appropriate comparison for this review. | |

| ALLOCATION: Not randomised | |

| ALLOCATION: Not randomised | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTIONS: Not CBT | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: High drop‐out (37%) | |

| ALLOCATION: Not randomised | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTIONS: Not CBT | |

| ALLOCATION: Randomised PARTICIPANTS: Patients with tinnitus INTERVENTIONS: Not CBT |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for tinnitus |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial (single‐blind) |

| Participants | All subjects will be veterans currently receiving care at VACHS Inclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria: (1) Tinnitus Impact Screening Interview (TISI) < 4 |

| Interventions | Two groups: (1) Education |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI). Eligibility pre‐treatment, post‐treatment, 8 weeks post‐treatment Secondary outcome: Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ). Eligibility, pre‐treatment, post‐treatment, 8 weeks post‐treatment. |

| Starting date | February 2009 |

| Contact information | Caroline J Kendall, Robert D Kerns. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Connecticut Health Care System, West Haven, Connecticut, USA |

| Notes | — |

| Trial name or title | Randomized controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety of individual cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) within the setting of the structured therapy programme sTCP (STructured Tinnitus Care Program) in patients with tinnitus aurium |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: (1) Tinnitus > 11 weeks Exclusion criteria: (1) Pulsatile, intermittent or non‐persistent tinnitus |

| Interventions | Individual application of structured and tinnitus specific cognitive behavioral therapy intervention procedures in the clinical setting of the structured therapy programme "tinnitus care program (TCP)" Duration of intervention per patient: 1 to 15 treatment sessions plus self‐treatment up to 16 weeks Control intervention: waiting group (16 weeks) |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Tinnitus Change Score (8‐point numerical scale) Secondary outcomes: Tinnitus Questionnaire Score (TQS), Tinnitus Loudness Score (TLS) and Tinnitus Annoyance Score (TAS) (6 to 8‐point numerical verbal scales) |

| Starting date | — |

| Contact information | hans‐[email protected]‐tuebingen.de |

| Notes | — |

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory

HRSD = Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression

ITHQ = Iowa Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire

MSPQ = Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire

PSCS = Private Self Consciousness Scale

SCL‐90R = Symptom Check List 90R

TEQ = Tinnitus Effect Questionnaire

THI = Tinnitus Handicap Inventory

TRQ = Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 6 | 354 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [‐0.02, 0.51] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): subjective loudness score, Outcome 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

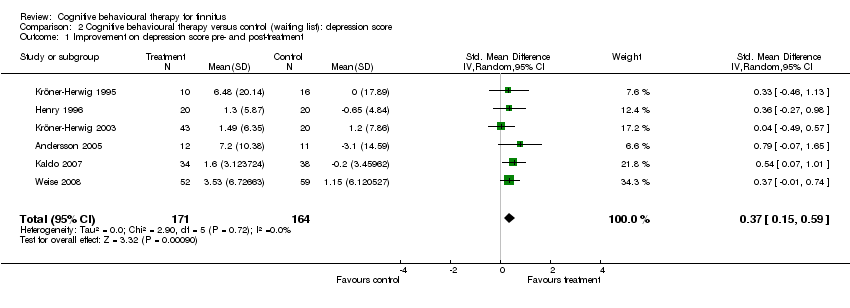

| 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 6 | 335 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.15, 0.59] |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): depression score, Outcome 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 5 | 309 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.50, 1.32] |

| Analysis 3.1  Comparison 3 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): quality of life score, Outcome 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 4 | 164 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.22, 0.42] |

| Analysis 4.1  Comparison 4 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): subjective loudness score, Outcome 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

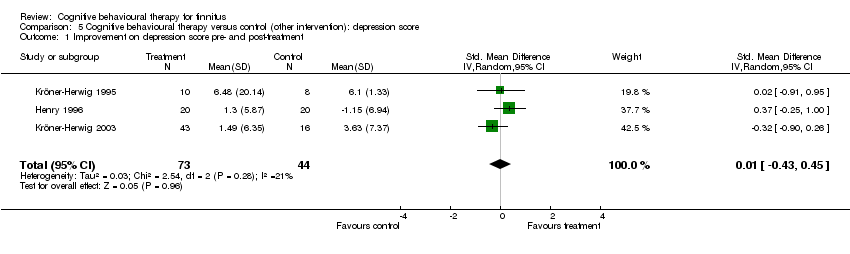

| 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 3 | 117 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.43, 0.45] |

| Analysis 5.1  Comparison 5 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): depression score, Outcome 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 3 | 146 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.29, 1.00] |

| Analysis 6.1  Comparison 6 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): quality of life score, Outcome 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment. | ||||

Comparison 1 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): subjective loudness score, Outcome 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 2 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): depression score, Outcome 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 3 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (waiting list): quality of life score, Outcome 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 4 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): subjective loudness score, Outcome 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 5 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): depression score, Outcome 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

Comparison 6 Cognitive behavioural therapy versus control (other intervention): quality of life score, Outcome 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 6 | 354 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [‐0.02, 0.51] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 6 | 335 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.15, 0.59] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 5 | 309 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.50, 1.32] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on subjective loudness score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 4 | 164 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.22, 0.42] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on depression score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 3 | 117 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.43, 0.45] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Improvement on quality of life score pre‐ and post‐treatment Show forest plot | 3 | 146 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.29, 1.00] |