Les interventions dans les médias de masse pour le sevrage tabagique chez les adultes

Résumé scientifique

Contexte

Les campagnes médiatiques de lutte antitabac peuvent atteindre un grand nombre de personnes. Une grande partie de la littérature est focalisée sur les effets de la publicité antitabac chez les jeunes, mais il existe également un certain nombre d'évaluations de campagnes visant les fumeurs adultes, qui montrent des résultats mitigés. Les campagnes peuvent être locales, régionales ou nationales, et peuvent être combinées à d'autres composantes d'une politique globale de lutte antitabac.

Objectifs

Évaluer l'efficacité des interventions dans les médias de masse dans la réduction du tabagisme chez les adultes.

Stratégie de recherche documentaire

La stratégie de recherche du groupe Cochrane sur le tabagisme a été combinée à d'autres recherches visant à identifier toutes les études se référant au tabagisme/sevrage tabagique, aux médias de masse et ciblant des adultes. Nous avons également effectué des recherches dans le registre Cochrane des essais contrôlés (CENTRAL) et dans un certain nombre de bases de données électroniques. La dernière recherche a été effectuée en novembre 2016.

Critères de sélection

Les essais contrôlés assignant des communautés, des régions ou des états à une intervention ou à une condition de contrôle ainsi que les séries chronologiques interrompues.

Les adultes, de 25 ans ou plus, fumant régulièrement des cigarettes. Les études ciblant tous les adultes, tels que définis dans les études, ont été incluses.

Les médias de masse sont définis ici comme étant des canaux de communication, tels que la télévision, la radio, les journaux, les panneaux publicitaires et les affiches ou les brochures visant à atteindre un grand nombre de personnes et ne dépendant pas d'un contact interpersonnel. Le but principal de la campagne médiatique devait être d'encourager les fumeurs à arrêter de fumer. Celles‐ci pouvaient avoir été offertes seules ou en association avec des programmes de lutte anti‐tabac.

Le critère de jugement principal était le changement du comportement tabagique. Celui‐ci pouvait être rapporté des manières suivantes : modification de la prévalence, modification de la consommation de cigarettes, des taux de sevrage, ou de la probabilité de devenir fumeur.

Recueil et analyse des données

Deux auteurs ont, de manière indépendante, évalué toutes les études sur la base des critères d'inclusion et évalué leur qualité (MB, LS, RTM). Un auteur (MB) a extrait les données et un second auteur (LS) les a vérifiées.

Les résultats n'ont pas été regroupés en raison de l'hétérogénéité des études incluses; ceux‐ci sont ainsi présentés de manière narrative et sous la forme d'un tableau.

Résultats principaux

Onze études répondaient aux critères d'inclusion pour cette revue. Les études variaient en termes de conception, de contexte, de durée, de contenu et d'intensité de l'intervention, de durée du suivi, de méthodes d'évaluation et également en termes de définitions et de mesures du comportement tabagique utilisées. Parmi les sept campagnes ayant rapporté la prévalence du tabagisme, des diminutions significatives ont été observées dans les campagnes de lutte anti‐tabac à échelle nationale réalisées en Californie et au Massachusetts en comparaison avec le reste des États‐Unis. Certains effets positifs sur la prévalence dans la population générale ou dans des sous‐groupes ont été observés dans trois des sept études restantes. Trois campagnes à grande échelle parmi les sept présentant des résultats sur la consommation de tabac ont constaté des diminutions statistiquement significatives. Parmi les huit études présentant des taux d'abstinence ou de sevrage, quatre ont montré un certain effet positif, bien que l'une de celles‐ci ait combiné les mesures du sevrage et de la diminution de la consommation. Parmi les trois études n'ayant pas montré de diminutions significatives, une étude a montré un effet significatif de l'intervention sur les fumeurs et sur les ex‐fumeurs combinés.

Conclusions des auteurs

Il existe des preuves indiquant que les programmes globaux de lutte antitabac incluant des campagnes médiatiques peuvent être efficaces pour modifier le comportement tabagique chez l'adulte, mais les preuves sont issues d'un groupe hétérogène d'études de qualité méthodologique variable. Un programme de lutte anti‐tabac (au Massachusetts) a montré des résultats positifs jusqu'à huit ans après la campagne. Un autre (en Californie) a montré des résultats positifs au cours de la période de mise en œuvre et lorsque le financement était adéquat ainsi que lors de l'évaluation finale depuis le début du programme. Six des neuf études menées dans des communautés ou dans des régions, ont montré certains effets positifs sur le comportement tabagique et au moins un changement significatif dans la prévalence du tabagisme (à Sydney). L'intensité et la durée des campagnes médiatiques peuvent influer sur l'efficacité, mais la durée du suivi et les tendances et les événements sociétaux concomitants peuvent rendre la quantification difficile. Aucune relation cohérente n'a été observée entre l'efficacité des campagnes et l'âge, l'éducation, l'origine ethnique ou le sexe.

Résumé simplifié

Est‐ce que des programmes de lutte antitabac incluant une campagne dans les médias de masse aident à réduire les niveaux de tabagisme chez les adultes ?

Contexte

Les programmes médiatiques de masse comprennent la communication par la télévision, la radio, les journaux, les panneaux publicitaires et les affiches ou les brochures ayant comme objectifs d'encourager les fumeurs à arrêter de fumer et à maintenir l'abstinence chez les non‐fumeurs. Il est difficile de déterminer leur rôle dans ce processus et ceux‐ci nécessitent une conception méthodologique rigoureuse.

Question de la revue

Évaluer l'efficacité des interventions dans les médias de masse dans la réduction du tabagisme chez les adultes.

Les caractéristiques de l'étude

Nous avons réalisé des recherches jusqu'au 30 novembre 2016, et nous avons trouvé 11 études pertinentes pour cette revue. Le nombre de participants variait entre les études incluses. Toutes les études portaient sur des adultes, bien que certaines incluaient également des personnes plus jeunes (ayant 14 ans ou plus ou 15 ans ou plus). Les campagnes ont inclus la publicité à la télévision, à la radio, dans la presse écrite et sur des panneaux publicitaires. Les études différaient en terme de contexte, de durée, de contenu de l'intervention, de durée des observations, et de mesures du comportement tabagique et dans leur manière de présenter les résultats. Deux campagnes ont rapporté des diminutions avérées de la prévalence du tabagisme, et certains effets positifs ont été observés dans trois autres. Trois campagnes à grande échelle ont rapporté une plus faible consommation de tabac. Trois études ont montré un certain effet positif au niveau de l'abstinence ou des taux de sevrage. Une étude n'a pas montré de diminutions significatives mais a démontré un effet de l'intervention chez les fumeurs et chez les ex‐fumeurs combinés.

Principaux résultats

Les programmes de lutte antitabac incluant des campagnes médiatiques peuvent modifier le comportement tabagique chez l'adulte, mais les preuves sont issues d'études de qualité variable, réalisées à des échelles différentes et surviennent souvent dans un environnement où il existe d'autres facteurs influençant le tabagisme, ce qui rend difficile d'isoler les effets de la campagne médiatique elle‐même. Aucun profil cohérent en termes d'âge, d'éducation, d'origine ethnique ou de sexe n'a été trouvé.

La qualité des preuves

Il y avait des problèmes au niveau de la conception et de la réalisation de toutes les études, ce qui a brouillé les preuves. Il serait utile que les futures études incluent des communautés n'étant pas exposées aux interventions dans les médias de masse comme comparateurs pour obtenir une meilleure estimation de l'effet de la campagne médiatique.

Authors' conclusions

Summary of findings

| Mass media smoking cessation intervention compared with no intervention for smoking cessation | ||||

| Patient or population: Adults who smoke Settings: Community Intervention: Mass media Comparison: No mass media | ||||

| Outcomes | Impact | No of | Quality of the evidence | Comments |

| Smoking prevalence (follow up from 6 months to 18 years) | The 2 state‐wide programmes, in which mass media campaigns were part of comprehensive tobacco control programmes, observed greater declines in smoking prevalence than in the rest of the USA. Of the 5 community‐based studies, 2 found significant decreases in smoking prevalence, 1 did not detect a significant effect, and of 2 studies conducted among Vietnamese‐American men, one detected a statistically significant decrease in smoking prevalence at 2 years, while the other did not. | 7 (n = 1,965,478)1 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | 2 studies were interrupted time series; and 5 were quasi experimental |

| Tobacco consumption (follow up from 2 to 18 years) | In the 2 state‐wide campaigns cigarette consumption was measured on the basis of aggregated sales data. In 1, a statistically significant decline was observed compared with the rest of the USA. In the other, declines in consumption were reported, but without statistical comparisons. Of the five community‐based studies, 1 study detected a significant reduction in cigarette or tobacco consumption for a high‐risk group, who also received counselling, but not in the media‐only intervention community compared with controls. The remaining 4 studies did not detect significant differences. | 7 (n = 1,964,292)1 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | 2 studies were interrupted time series and 5 were quasi experimental |

| Abstinence or quit rates (follow up from 6 months to 18 years) | Among the 8 studies presenting abstinence or quit rates, 4 showed some positive effect. 1 state‐wide campaign presented the quit ratio (i.e. the percentage of ever‐smokers (current and former) who were ex‐smokers in a given year), finding a statistically significant difference in favour of the intervention. The other 7 studies were community based; of these, 4 detected a statistically significant effect in favour of the intervention across the study population, 1 found statistically significant differences only in women, 1 study reported a non‐statistically significant difference in point prevalence of daily smoking, and 1 detected no significant differences. | 8 (n = 987,800)1 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | 1 study was quasi RCT and 7 were quasi experimental |

| Quit attempts (follow‐up from 7 months to 18 years) | Of the 5 studies that assessed quit attempts, 3 were community‐based studies, and 2 were state‐wide campaigns. 2 community‐based studies among Vietnamese‐American men found no significant differences between the intervention and control communities. A third study only assessed quit attempts among participants still smoking at follow‐up, of whom 27.3% had made quit attempt. 2 state‐wide campaigns assessed quit attempts only in the intervention community. In 1 they increased in line with campaign duration but not to a statistically significant extent, in the other the percentage of smokers with a quit attempt in the last year increased over the duration of the study, but without statistical comparisons. | 5 (n=1,947,674)1 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | 2 studies were interrupted time series and 3 studies were quasi experimental |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||

| 1 Estimated participant numbers based on the number of respondents to surveys and the number of participants at follow up in the quasi‐experimental studies. 2 GRADE rating started at 'low': none of the studies were RCTs. One was a quasi‐RCT, two were interrupted time series and eight were quasi‐experimental. 3 Downgraded one level for inconsistency: included studies varied in design, intervention, comparator and population, and results were not homogenous. | ||||

Background

It is estimated that about 820 million men over the age of 15 and about 176 million women are daily smokers (Eriksen 2015). World wide, tobacco is the leading cause of preventable death, killing nearly 6 million people each year, with 80% of deaths occurring in low‐ and middle‐income countries (WHO 2015). It is estimated that if no additional measures are introduced the smoking prevalence in 191 countries included in the Global InfoBase Database of the World Health Organization (WHO) will be 22.7% in 2020 and 22% in 2030, accounting for 872 million smokers (Mendez 2012). In 2003 the World Health Assembly adopted the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which was ratified by 180 parties, covering about 90% of the world's population (WHO FCTC 2003; WHO 2015). To assist those countries in implementation of effective interventions to reduce the demand for tobacco in 2008, the WHO disseminated recommendations called MPOWER, which included the following strategies: monitor tobacco use, protect people from tobacco smoke, offer help to quit tobacco use, warn about the dangers of tobacco, enforce bans on tobacco advertising promotion and sponsorship, and raise taxes on tobacco (WHO 2008). Article 12 of the FCTC requires signatories to promote and strengthen public awareness of tobacco control issues using available communication tools, including mass media campaigns (WHO 2015).

Mass media interventions consist of the dissemination through television, radio, print media and billboards, of cessation‐related messages, informing smokers and motivating them to quit. Mass media campaigns can be effective in keeping tobacco control on the social and political agenda, in legitimising community action and in triggering other interventions. Campaigns are designed either directly to change individuals' smoking behaviour (the risk factor model), or to catalyse other forces of social change (the social diffusion model), which may then lead to a change in social norms about smoking (Wellings 2000). Social diffusion campaigns, such as those run in Australia, Canada, Thailand, the United Kingdom and some US states, are designed to de‐normalise smoking, so counteracting the tobacco industry's message that smoking is desirable and harmless (WHO 2001).

Research into the effectiveness of mass media campaigns is generally conducted through community trials. This term includes both randomised and non‐randomised studies which involve whole communities as the unit of assignment, with data collection from individuals within the communities. Murray 1998 has identified four main features which differentiate the designs of such studies, and which are generally determined by the nature of the research question.

(i) Main effects (to assess the impact of a single intervention) versus factorial (to assess the impact and sometimes the interaction of two or more variables).

(ii) Data collection schedules: these can range from a single post‐intervention measurement of the groups, through two or more series of assessments (including pre‐intervention baseline measures), to continuous surveillance.

(iii) Cross‐sectional versus cohort: cross‐sectional designs are appropriate when the investigators are concerned with the impact of the intervention on the population as a whole, while cohort designs are more suited to measuring behaviour change in individuals over time.

(iv) A priori matching and stratification may help to limit bias and improve precision.

Analysis 1.1, 'Response and Retention Rates', summarises the design characteristics of the studies included in this review.

Mass media tobacco control campaigns in the USA began in 1967, following the publication of the 1964 Surgeon General's report on smoking and health (Surgeon General 1964). The Federal Communications Commission enforced the Fairness Doctrine, obliging radio and television stations to broadcast one tobacco control message for every three cigarette commercials (equivalent to a media value today of USD 300 million (WHO 2001)). This policy lasted until 1970, when a ban on broadcast cigarette advertising came into effect. Cigarette consumption had declined by 37% during the campaign, but began to rise again after the advertising ban ended free access to broadcast time for tobacco control messages (Warner 1977; USDHHS 1991).

Mass media campaigns in the 1970s tended to be based on the premise that information and heightened public awareness would of themselves effect changes in cultural norms and smoking behaviour. This assumption was challenged by the social learning theory approach, which held that public attitudes to smoking were more successfully translated into behaviour change if the mass media campaign was combined with well‐targeted interpersonal interventions conducted by healthcare workers or other credible agencies. This approach also acknowledged the importance of role models and peer‐group pressure and support in changing behaviour (Bandura 1977; Flay 1987b; NCI 1991). Later campaigns, the 'second generation' model, concentrated more on developing personal skills to cope with social and media pressure, and to recognise and resist tobacco industry advertising; they were also more likely to help smokers and non‐smokers to improve their decision‐making and problem‐solving abilities (Logan 1999). Such an approach, however, did not address the continuing dissonance between 'expert' opinion (scientists, healthcare providers, policy‐makers, many non‐smokers) and those smokers who resented the paternalism of campaigners, and who may have had complicated cultural and emotional attachments to their smoking, independently of their physical addiction (Yankelovich 1991; Logan 1999; Hastings 2002).

A number of studies suggest that media‐supported cessation campaigns can be an effective part of comprehensive and synergistic tobacco control programmes, reaching individuals directly with cessation messages and influencing their knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. Campaigns have been run and evaluated in a number of countries, including Australia, Canada, France, Iceland, New Zealand, the Philippines, Poland, Singapore and the UK, and in Arizona, California, Kansas, Massachusetts, Florida, Minnesota and Oregon within the USA (Flay 1987a; USDHHS 1991; WHO 2001). According to a 2015 WHO report, more than half of the countries in the world, covering 40% of the population implemented at least one MPOWER measure (without mass media), 39 countries ran national anti‐tobacco media campaigns fulfilling all the WHO requirements (WHO 2015), while a further 30 countries conducted campaigns fulfilling most but not all of those requirements. In total 55% of the world's population received in the previous two years at least one anti‐tobacco mass‐media campaign lasting at least three weeks (WHO 2015).

Previous reviews of the literature lend some support to tobacco control media campaigns as a component of comprehensive tobacco control programmes (World Bank 1999; Fiore 2000). Much of the literature is focused on the effects of tobacco control advertising on young people (Reid 1995; Tyas 1997; Pechmann 2000; Wakefield 2000; Wakefield 2003), but there are also a number of evaluations of campaigns targeting adult smokers, which show mixed results. Some national and state‐wide interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing smoking rates, while the outcomes are less consistent for community and local campaigns (Flay 1987a; Flay 1987b; Levy 2000; NCI 2000; Hopkins 2001; WHO 2001; Friend 2002; Siegel 2002a; Siegel 2002b).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of mass media interventions in reducing smoking among adults.

We addressed the following questions.

1. Do mass media campaigns reduce smoking (measured by prevalence, cigarette consumption, quit attempts and quit rates) compared with no intervention in comparison communities?

2. Do mass media campaigns, run in conjunction with tobacco control programmes, reduce smoking, compared with no intervention or with tobacco control programmes alone?

3. Which characteristics of these studies are related to their efficacy?

4. Do mass media tobacco control campaigns cause any adverse effects?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

-

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials allocating communities, regions or states to intervention or control conditions.

-

Controlled trials without randomisation, allocating communities, regions or states to intervention or control conditions.

-

Interrupted time series.

Uncontrolled before‐and‐after studies, and uncontrolled studies with post‐intervention measurements but no baseline measurement were excluded.

Types of participants

Adults, 25 years or older, who regularly smoke cigarettes. Studies which cover all adults as defined in studies were included. Studies addressing only adolescents and 18‐ to 25‐year‐olds are covered in a separate Cochrane Review (Brinn 2010).

Interventions for pregnant women were excluded, since this topic is covered by a separate Cochrane Review (Lumley 2009).

Types of interventions

Mass media are defined here as channels of communication such as television, radio, newspapers, billboards, posters, leaflets or booklets intended to reach large numbers of people, and which are not dependent on person‐to‐person contact. The purpose of the mass media campaign must be primarily to encourage smokers to quit. They could be carried out alone or in conjunction with tobacco control programmes. Studies of comprehensive programmes were included, provided that the comparison was structured in such a way that the contribution and efficacy of the mass media component could be assessed.

Interventions comprising competitions and incentives or 'quit and win' contests are covered by other Cochrane Reviews (Cahill 2008; Cahill 2011). Internet‐based interventions and mobile‐phone interventions are covered by other Cochrane Reviews (Civljak 2010; Whittaker 2012).

Types of outcome measures

Measures of smoking behaviour

-

Primary: tobacco cessation, covered by prevalence rates, quit rates.

-

Secondary: tobacco reduction, covered by changes in the number of cigarettes purchased or smoked, prevalence of daily smoking, quit attempts.

We prefer outcomes measured at the longest follow‐up, and at least six months from the beginning of the intervention. It is generally not feasible for community trials to conduct biochemical validation of their smoking cessation results, and we do not require this of the included studies in this review.

Intermediate measures

-

Attitudes to smoking.

-

Knowledge about smoking, including smoking norms, and effects of tobacco on health.

-

Adverse side effects.

Process measures

-

Descriptions of formative research, pilot studies and ongoing evaluation and modification of the intervention.

-

Media weight (reach, frequency and duration), campaign awareness/exposure.

-

Dose‐response relationships (e.g. volume of calls to telephone helplines).

-

Maintenance of programmes after the interventions were completed.

-

Intervention costs.

Mass media campaigns that have only been reported in terms of intermediate outcomes or process measures were excluded.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register was searched for reports of evaluations of mass media campaigns. See Appendix 1 for strategy. The register is derived from sensitive searches for trials and other evaluations of tobacco control and smoking cessation interventions; see the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies. At the time of the search in November 2016 the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 9, 2016, in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20160923; Embase (via OVID) to week 201639; and PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20160926. Additional databases searched for early versions of this review are no longer checked.

Data collection and analysis

One reviewer prescreened all search results (abstracts), for possible inclusion or as useful background. Three reviewers (MB, LS and RTM) independently assessed relevant studies for inclusion and resolved discrepancies by consensus. The editorial base would have resolved any persistent disagreements. The reviewers noted reasons for the non‐inclusion of studies.

One reviewer (MB) extracted data, and a second reviewer (LS) checked them. This stage included an evaluation of quality. Two reviewers independently assessed each study according to the presence and quality of the randomisation process, whether the analysis was appropriate to the study design, and the description of withdrawals and drop‐outs. They assessed interrupted time series studies according to criteria defined by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC 2006). These require a minimum of three assessments before the intervention and three afterwards for the study to be included in the review.

We extracted data on:

-

country and community status (e.g. state, city);

-

participants (baseline demographic, clinical and smoking characteristics);

-

intervention (duration, intensity, message development);

-

outcomes, and how they were measured;

-

length of follow‐up;

-

completeness of follow‐up;

-

definition of smoking cessation;

-

biochemical confirmation of abstinence, if present.

In cases of missing data, we contacted the authors of the study where possible.

Due to the expected heterogeneity of included studies we did not pool results but present them narratively and in the Results Tables. Eligible studies differed significantly in design, setting, duration, content and intensity of intervention, length of follow‐up, methods of evaluation and also in definitions and measures of smoking behaviour used.

'Summary of findings' table

Following standard Cochrane methodology, we created a 'Summary of findings' table for our primary outcomes. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for that outcome.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

From our update searches, the latest of which was performed in November 2016, we identified 1507 studies. Based on titles and abstracts we excluded 1337 references, resulting in 170 full papers to be retrieved. In addition, we found 17 references through handsearching and from the websites of included mass media campaigns. We therefore retrieved 187 full‐text papers. Based on these, we excluded 1762 papers.

For this update we identified three reports updating the California TCP campaign (California TCP 2003), four reports from the Massachusetts TCP campaign (Massachusetts 2003), and one new excluded study (Figure 1).

Prisma flow diagram of search results

Included studies

We identified 11 campaigns meeting our inclusion criteria. Detailed information about each is shown in the table Characteristics of included studies. Sixty‐five excluded studies and reasons for exclusion are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Eight studies had strong designs comparing the effect of mass media campaigns in exposed areas to control areas, using indices of smoking behaviour (mainly prevalence) in the whole population (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997; McVey 2000; McAlister 2004). One study had a similar design, but assessed the effect of the intervention by examining the abstinence rates achieved in one clinic each in the intervention and control areas (Mogielnicki 1986). Two studies had strong controlled designs (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003), but the intervention areas were exposed to mass media campaigns plus a range of other tobacco control interventions as compared to no special interventions in control areas. Study sites ranged from the USA (Stanford 3 City 1977; Mogielnicki 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004); to the UK (McVey 2000); South Africa (CORIS 1997); and Australia (North Coast QFL 1983; Sydney QFL 1986).

Characteristics of study populations

Study populations were diverse. All studies involved adults, although the age of adulthood varied between studies. Eight studies targeted both men and women, and three targeted men only (Mogielnicki 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997). Two studies targeted male Vietnamese immigrants in the USA (McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997). Two state‐wide campaigns targeted adults, adolescents and the general population (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003).

Characteristics of interventions

In six studies the theoretical basis for the development of the intervention was described. In Stanford 3 City 1977 social marketing theory, social learning theory and communication theory underpinned the intervention, while McAlister 2004 specified social learning theory, the transtheoretical model and elements of modelling, social reinforcement for behaviour change and emotional arousal. California TCP 2003 and Massachusetts 2003 both used social diffusion theory with social marketing and social policy change. North Coast QFL 1983 cited social marketing and communication theory, and Mogielnicki 1986 specified current marketing methodology in developing its mass media campaign. In the remaining five studies no theoretical basis was specified.

Two campaigns conducted as part of tobacco control programmes involved TV, radio, print media and billboard advertising (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003). One study used only TV advertising (McVey 2000); one used TV and radio advertising (Mogielnicki 1986); one study used only billboards, posters, mailings and local newspapers (CORIS 1997). The remaining studies used TV, radio and print media, and billboards or posters or both (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; McAlister 2004). Two studies aimed at the reduction of cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking, diet, blood pressure, cholesterol, sedentary lifestyle, and stress (Stanford 3 City 1977; CORIS 1997), while the remaining nine studies aimed specifically at changing smoking behaviour (reducing smoking prevalence, reducing the number of cigarettes smoked or increasing quit rates).

The two state‐wide campaigns, California TCP 2003 and Massachusetts 2003, were each part of a wider tobacco control programme which implemented a number of public policy measures to reduce smoking, but we have not included those outcomes in our review.

Assessments

Cross‐sectional independent surveys were used in five studies (North Coast QFL 1983; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003); cohort follow‐up in two studies (Mogielnicki 1986; McVey 2000); and both methods in four studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997; McAlister 2004).

Three studies reported follow‐up beyond the duration of the intervention and the immediate post‐intervention assessment, at 12 years for CORIS 1997, at 18 months for McVey 2000, and at one year for Sydney QFL 1986. Stanford 3 City 1977 reported one additional year of follow‐up for the high‐risk group only.

Interviews were conducted in person in six studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997; McVey 2000), by telephone in four studies (McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004), and by both methods in California TCP 2003. In addition to the interviews, physical examination and blood tests were carried out in three studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; CORIS 1997).

In most studies smoking abstinence was self‐reported, and was biochemically confirmed in all participants in only two studies: Stanford 3 City 1977 checked plasma thiocyanate, and Mogielnicki 1986 checked plasma thiocyanate and exhaled carbon monoxide. Subsamples of participants were tested for salivary cotinine in Sydney QFL 1986, and for plasma thiocyanate in North Coast QFL 1983.

Outcome measures

Difference in smoking prevalence was the main outcome measure in seven campaigns (North Coast QFL 1983; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003). One study reported it for the high risk group only (Stanford 3 City 1977).

Changes in the number of cigarettes (or grams of tobacco) smoked were reported in five studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997), and was the main outcome for Stanford 3 City 1977.

In seven studies quit rates or abstinence rates were reported (Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997; McVey 2000; California TCP 2003), and were the main outcome in two studies (Mogielnicki 1986; McVey 2000).

In McAlister 2004, point prevalence of daily smoking (ceasing to smoke at all or every day) was reported as the main outcome. In the two state campaigns per capita cigarette consumption based on aggregate sales data was also presented (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003).

The number of quit attempts was reported in six studies (Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004).

Intermediate measures

Attitudes to smoking were assessed at baseline in nine studies (North Coast QFL 1983; Mogielnicki 1986; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997; McVey 2000; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004), with follow‐up data provided in five of them (North Coast QFL 1983; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003), but in one study only in graphical form (North Coast QFL 1983).

Social pressure/influences in the decision to quit were assessed in four studies at baseline and at follow‐up (North Coast QFL 1983; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; Massachusetts 2003).

Norms concerning smoking behaviour were assessed in three studies at baseline and at follow‐up (McPhee 1995; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003): in McPhee 1995 this was assessed by the number of friends or household members smoking and giving advice or being advised to stop smoking. In the two state‐wide campaigns norms were assessed by measuring support for tobacco control legislative measures and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke at work and at home, but only within the intervention communities and not for the controls.

Information‐seeking behaviour in the population was assessed at baseline and at follow‐up in one study (Sydney QFL 1986).

Knowledge and/or beliefs about cardiovascular risk factors or the effects of smoking were assessed at baseline in eight studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004).

Follow‐up data were provided in six studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003), but in one study only in graphical form without elucidation in the text (North Coast QFL 1983).

No study reported adverse effects of the campaigns.

Process measures

Formative research or pilot studies were used in nine campaigns (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; Jenkins 1997; McVey 2000; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004). No information was provided for two campaigns (McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997). Ongoing evaluation and modification of the intervention was reported in five studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; McVey 2000; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003).

Detailed information regarding media weight (numbers of TV and radio spots, newspaper articles etc.) was provided in five studies (Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; California TCP 2003), and summary information was given in four studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; CORIS 1997; McVey 2000; Massachusetts 2003). Little or no information was given in McAlister 2004 or North Coast QFL 1983.

Awareness and reach of the intervention was measured in seven studies (Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004) with only McAlister 2004 not reporting numerical data for this outcome.

Dose response: some evidence on possible dose‐response relationships was mentioned, either as numbers of calls to quitlines (Sydney QFL 1986; McVey 2000), as increasing knowledge with increasing intensity of the intervention (Stanford 3 City 1977), or as increasing cessation rates, number of quit attempts, or changes in social norms with increasing numbers of channels or intensity of intervention (California TCP 2003; McAlister 2004). In McVey 2000 abstinence rates were compared in two study areas which received single‐ or double‐weight interventions. No study presented a formal dose‐response analysis.

Maintenance: the campaigns were maintained beyond the intervention period in six studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997; McVey 2000; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003). In one study the campaign was continued beyond the final assessment point for one year, but with reduced intensity and no additional evaluation (Stanford 3 City 1977). The CORIS 1997 campaign was subsequently maintained by the community, but no details are given. The McVey 2000 campaign was continued nationally after a controlled evaluation. In Sydney QFL 1986 the mass media campaign was run in later years for a few weeks, with assessment of long‐term success. The two state‐wide campaigns were established as constitutional amendments, so they remained in place (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003).

Intervention costs: costs per capita were reported in four studies (CORIS 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004), and total campaign costs in four studies (Sydney QFL 1986; Mogielnicki 1986; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003). Some cost‐effectiveness analysis was performed for the two state‐wide campaigns (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003). No economic evaluation was reported for five campaigns (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; McVey 2000).

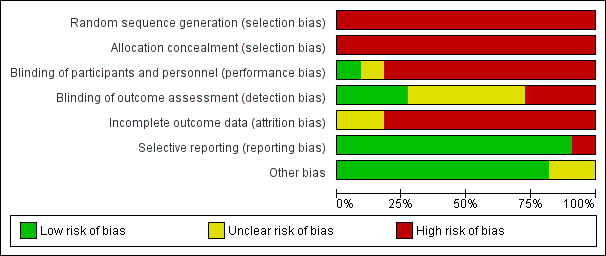

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, we assessed the risk of bias of the included studies as high. For an overview of the methodological quality of the included trials see Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Mogielnicki 1986 randomised clinic attenders to different interventions within each clinic assigned to intervention or control conditions. It is normally not feasible or affordable to use true randomisation in community studies of this kind. Nine were of quasi‐experimental design, with intervention and control status non‐randomly allocated (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997; McVey 2000; McAlister 2004). The two state‐wide campaigns were assessed through an interrupted time series design comparing the effects of the campaigns as part of tobacco control programmes with other US states where there were no campaigns.

Selection of participants for outcome measures

Samples of participants were selected in most studies through random digit dialling, or through selecting from enumeration lists or telephone books. In one study the total population was surveyed (CORIS 1997).

Response rates and retention rates

Response rates (applicable to nested cross‐sectional analyses) were reported in nine campaigns. Three of them reported the combined rates for the intervention and control communities (Sydney QFL 1986; California TCP 2003; McAlister 2004); and five reported them separately (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997). Massachusetts 2003 reported combined and separate response rates. In those studies reporting separately for intervention and control communities, the response rates at baseline ranged from 70% to 84% in the intervention communities, and from 64% to 82% among the controls. The follow‐up response rates for those studies ranged from 68% to 94% for intervention communities, and from 62% to 88% for the controls. The response rates combined for intervention and control community varied between 42.7% and 99.4%.

Retention rates (applicable to cohort analyses) were reported in six studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997; McVey 2000; McAlister 2004), and ranged from 53.5% to 76% in the intervention communities and from 52% to 73% in the controls. Two studies provided some information on participants lost to follow‐up (McVey 2000; McAlister 2004); and Sydney QFL 1986 surveyed non‐responders in Sydney and Melbourne at baseline, for evidence of selection bias. Among the cohort studies, CORIS 1997 reported on demographic differences between cohort and non‐cohort participants (i.e. those who had only responded to one of the surveys); and Stanford 3 City 1977 identified higher smoking prevalence and heavier daily smoking among non‐cohort participants than in the cohorts. Study design, with detailed response and retention rates, are shown in Analysis 1.1.

Comparability of intervention and control community at baseline

Nine studies described the demographic characteristics of participants at baseline (Stanford 3 City 1977; Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997; McVey 2000; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004), with six of them conducting statistical tests for comparability (Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004). In North Coast QFL 1983 the statistical comparisons are reported without numerical detail. California TCP 2003 did not provide any information on comparability of the population. The intervention and control communities were shown to be demographically disparate in three studies, with analyses controlling for those differences (McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997; Massachusetts 2003). Sydney QFL 1986 tested for possible confounding by sex, age, education, marital status, and socio‐economic status, but found none of them to be predictive of quitting.

Blinding

Only one study reported blinding participants and personnel (McVey 2000); in other studies it was unclear if they were blinded. Three studies reported on blinding outcome assessors (McAlister 2004; McVey 2000; Mogielnicki 1986); in other studies it was unclear if they were blinded.

Incomplete outcome data

None of the included studies reported attrition rates or losses to follow‐up.

Selective reporting

Only one trial did not report the outcomes as prespecified in the Methods section (McAlister 2004), with all the other studies reporting outcomes as prespecified.

Other potential sources of bias

Other sources of bias were not identified in most studies. The California TCP 2003 and the Massachusetts 2003 campaigns were interrupted time series studies. Both had clearly defined time points when the intervention was conducted, with at least three data points before and three after the intervention. It was unclear whether other quality assessment criteria for interrupted time series had been fulfilled.

Evaluation process

In six campaigns the evaluation was done by study investigators (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Mogielnicki 1986; McPhee 1995; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997). In the remaining five included studies independent organisations conducted the evaluation or surveys or some parts of the work (Sydney QFL 1986; McVey 2000; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004). National surveys were conducted for the Californian and Massachusetts state‐wide campaigns.

Statistical analysis

Two of the 11 included studies reported sample size calculations (McPhee 1995; McVey 2000). However, because of the variability of the effect sizes we do not consider that the absence of a power calculation should be interpreted as a marker of lower quality. All the studies except CORIS 1997, which reported use of t‐tests with and without covariance adjustments, used regression analyses to produce their results. Two studies reported one‐sided P value tests (Stanford 3 City 1977; McAlister 2004); and CORIS 1997 used two‐sided P value tests.

The Californian and Massachusetts campaigns were described using an interrupted time series design. We assessed the reports according to the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group criteria (EPOC 2006). All the studies identified a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred, and at least three assessment points before and three after the intervention. However, the impact of the intervention independent of other changes was not clearly established. The TCP studies used regression models for data analysis. The intervention was deemed unlikely to affect data collection, and sources and methods of data collection were consistent before and after the intervention. Smoking prevalence was self‐reported and unvalidated. In two of the studies (one for each campaign) aggregated cigarette sales data were used as an objective measure. None of the studies reported on completeness of data sets, but did report response rates for outcome surveys.

Effects of interventions

See: Summary of findings for the main comparison

Detailed results are presented in 'Intermediate measures' (Analysis 1.2) and 'Primary measures of smoking behaviour' (Analysis 1.3). Summary findings on theoretical orientation, costs and outcomes are reported in 'Study summary by type of outcome' (Analysis 1.4). Baseline differences and possible confounders are reported in Analysis 1.5.

Smoking prevalence

Among the seven campaigns reporting smoking prevalence, two studies reported smoking prevalence separately for men and women (North Coast QFL 1983; CORIS 1997), and also by age group in North Coast QFL 1983. Three studies reported prevalence for the whole population (California TCP 2003), and for men and women separately (Sydney QFL 1986; Massachusetts 2003). Two studies targeted and reported on men only (McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997), and the Stanford 3 City 1977 study reported in detail only on the high risk cohort. In three studies smoking prevalence was not reported (Mogielnicki 1986; McVey 2000; McAlister 2004).

Decreases in smoking prevalence were observed in both of the state‐wide programmes compared with the rest of the USA (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003), but in California the decrease was statistically significant only during the early period of the campaign, before cuts in funding. The final assessments of the California TCP showed greater decline of smoking prevalence since the beginning of the programme compared with the rest of the USA and lower smoking prevalence, but the statistical significance of the differences was not reported. In the Massachusetts campaign the decrease was statistically significant for the population as a whole and for men, but not for women. It should be noted that the mass media campaigns in both states were part of a comprehensive programme of tobacco control measures.

Among those studies which analysed men and women separately, both the Australian studies detected significantly decreased prevalence among men and women (North Coast QFL 1983; Sydney QFL 1986), while two studies found significant reductions in men's but not women's smoking at long‐term follow‐up (Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997 at 12 years). For the two studies that examined Vietnamese men's smoking, Jenkins 1997 detected a significant decrease in prevalence at two‐year follow‐up, while McPhee 1995 failed to detect a significant reduction. Stanford 3 City 1977 failed to detect a significant effect of the media‐only intervention on prevalence compared with controls at three years, although the declining trend favoured the control community.

Cigarette consumption

Among the seven campaigns reporting cigarette consumption, one study presented cigarette consumption separately for men and women (CORIS 1997); two studies for men only (McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997); and two studies for the population as a whole (Stanford 3 City 1977; Sydney QFL 1986). Stanford 3 City 1977 detected a significant reduction in cigarette or tobacco consumption for the high‐risk group, but not in the media‐only intervention community compared with controls. The remaining studies failed to detect significant differences.

In the two state‐wide campaigns cigarette consumption was measured on the basis of aggregated sales data (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003). In California a significant decline was observed compared with the rest of the USA. In Massachusetts, declines in consumption were reported, but without statistical comparisons.

Quit attempts

Of the five studies that assessed quit attempts, two found no significant differences between the intervention and control communities (McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997); and McAlister 2004 only assessed quit attempts among continuing smokers. The two state‐wide campaigns assessed quit attempts only in the intervention community (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003). In Massachusetts they increased in line with campaign duration but not to a statistically significant extent, while in California rate changes were reported, but without statistical comparisons.

Quit rates

Eight studies reported quit rates or abstinence rates, with only one study reporting separately for men and women (CORIS 1997). Three of the studies included men only (Mogielnicki 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997). The California TCP 2003 presented the quit ratio, i.e. the percentage of ever‐smokers (current and former) who were ex‐smokers in a given year, and McVey 2000 gave quit rates for smokers and abstinence rates for ex‐smokers. McAlister 2004 reported point prevalence of daily smoking (ceasing to smoke at all or every day). This study also detected a benefit of 3% in quit rates (8% versus 5%) between study areas that received a media campaign and no cessation services, compared with areas without either intervention. This difference, however, was not statistically significant.

CORIS 1997 found significant differences in intervention quit rates for women but not for men, compared to controls. Two studies found significant intervention effects (Mogielnicki 1986; Jenkins 1997), while in Sydney QFL 1986 the quit rate was not reported separately from the smoking reduction rate. Significant differences were not detected in California TCP 2003 or McPhee 1995. McAlister 2004 reported no significant change in the point prevalence of daily smoking. McVey 2000 detected a significant intervention effect of the media campaign on abstinence rates for smokers and ex‐smokers combined at 18 months.

Intermediate measures

Five of six studies presenting follow‐up results for knowledge or beliefs data found some increases in knowledge about smoking or cardiovascular risk factors (Stanford 3 City 1977; Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997 (women only); California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003), with only North Coast QFL 1983 failing to detect a significant change.

Among five studies presenting follow‐up data on attitudes to smoking or cardiovascular risk factors, three found no significant differences between the intervention and control communities (North Coast QFL 1983; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997). The Californian and Massachusetts TCP campaigns found significant change compared with the period before the campaign, but there were no comparisons with other states (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003).

Information‐seeking behaviour, measured as the number of calls to quitlines, enrolments in 'quit centres' and the number of 'quit kits' sold, was reported as increased in Sydney QFL 1986.

Social influences or pressure to quit compared with baseline rates did not change in one study (North Coast QFL 1983), and increased in three studies (Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; Massachusetts 2003) — in McPhee 1995 there was no difference between the intervention and control communities at the follow‐up, while in the Massachusetts and Sydney studies no comparison with the control community was reported. Norms concerning smoking changed compared to baseline in all three studies which measured them (McPhee 1995; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003), but McPhee 1995 found no difference between the intervention and control communities, and in the state‐wide campaigns no comparison was made with non‐intervention states.

Process measures

Details of mass media campaign awareness in the intervention community comparison with the control community was presented in two studies and in both was significantly higher in the intervention community (McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997). None of the studies presented formal dose‐response analysis of intervention effects.

Intervention costs

Cost‐effectiveness data were presented for two state‐wide campaigns (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003). They indicated that both campaigns brought benefit in terms of decreases in the number of cigarette packs sold per capita per year for each per capita dollar spent on the media campaign. The effect was more pronounced in California than in Massachusetts. Per capita media expenditure was reported in four studies (CORIS 1997; California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003; McAlister 2004), and ranged from USD 0.25 and USD 3.35 per person per year. Two studies reported raw campaign costs (Mogielnicki 1986: copy development and production USD 7480, broadcast time USD 15,150; Sydney QFL 1986: AUD 620,000 for media and a 'Quit Centre'), but without attempting any cost benefit analysis.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Eleven mass media campaigns met our inclusion criteria for this review. Two state‐wide tobacco control programmes with mass media campaigns (California TCP 2003; Massachusetts 2003) and six out of nine community studies (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; CORIS 1997; Jenkins 1997) showed some positive effects on smoking behaviour, and at least one significant change in smoking behaviour (McVey 2000), although the increase in abstinence was for smokers and ex‐smokers combined.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The inclusion criteria for this review (requiring a comparison community) were designed to help us to identify and assess the specific contribution of the mass media to changing smoking behaviour. However, mass media campaigns are rarely the only component of a community‐based smoking cessation intervention, and it is often difficult or impossible to disentangle the contribution that the separate elements make to the overall impact of a comprehensive tobacco control programme.

The advantage of assigning a community to control 'no campaign' status should be that broad secular trends in smoking behaviour may more easily be distinguished from the specific effect of the intervention being tested. Despite this methodological strength, several of the studies in our review reported confounding of their findings by extraneous or concurrent events. For example: the findings of the baseline survey for the CORIS 1997 study directly contributed to the establishment of the Heart Foundation of Southern Africa, which then set up a number of tobacco control initiatives that may have contaminated CORIS's subsequent findings; the North Coast QFL 1983 campaign came under attack from the tobacco industry and was briefly suspended, with the resulting national publicity assumed to have influenced smoking behaviour in the control community; and during the Sydney QFL 1986 programme, which led to a 2.8% decrease in local prevalence, cigarette prices in Sydney rose less than in the rest of Australia, which may have masked some of the positive effects of the campaign. While such interactions may demonstrate the synergy between campaigns and societal changes, they compromise our ability to measure the impact of such research.

Mass media campaigns are inherently difficult to evaluate, since large samples are required to detect relatively small effects on individual members of the target community. However, even small changes may deliver significant benefits at the population level. McVey 2000 extrapolated that the odds ratio (1.53) for being a non‐smoker following the HEA tobacco control TV campaign would yield a decline in prevalence of 1.2% in a stable population with a smoking rate of 28% (the approximate prevalence rate in the UK at that time (ASH 2007)). There is also evidence that a memorable media campaign, particularly a TV‐based one, may increase calls to quitlines, the distribution of 'quit kits' and enrolment in treatment programmes, but that these may be transient responses, and do not necessarily translate to an increase in successful quit attempts. Low success rates and high drop‐out rates may be a consequence of unrealistically high expectations raised by a successful campaign (Sydney QFL 1986).

None of our included studies tested simply a mass media intervention. Some compared groups receiving a mass media intervention alone with groups receiving mass media and community interventions. In these cases only the mass media groups were included in our review (Stanford 3 City 1977; North Coast QFL 1983; CORIS 1997; McVey 2000; McAlister 2004). In some studies the intervention was led by a mass media programme but also included components such as quitlines, physician involvement and clinics (Mogielnicki 1986; Sydney QFL 1986; McPhee 1995; Jenkins 1997). We decided to include all studies in which a mass media programme led the intervention, but this has involved complex processes of evaluation and comparison.

The definitions of smoker, ex‐smoker and quitter varied from study to study, making between‐study comparisons problematic. In addition, the surveys used in both the state‐wide tobacco control programme (TCP) campaigns modified their definition of a smoker during the course of the campaigns. Because of those differences, people who were defined as smokers, ex‐smokers or quitters might not have fallen into those categories in another study. Some studies included both smoking cessation and smoking reduction as primary objectives; and in one study the criterion for success changed retrospectively from complete cessation to no longer smoking every day (McAlister 2004).

The state TCP campaigns were both introduced as constitutional amendments, and are funded from tobacco excise tax increases. They are to be continued, but with reduced funding and less aggressive advertising. Compared with smoking prevalence before the programme and in other states before and after the programme, the early campaign in California was associated with significant decreases in smoking prevalence. However, the early success was not sustained through the later stages of the campaign. The final evaluation up to 2008 showed a faster decline in smoking prevalence compared with the rest of the USA population. In addition smoking‐attributable cancer mortality rates declined more in California than in the rest of the USA (18.8% vs 2.4%) during 1979 to 2002 (California TCP 2003)

Fichtenberg 2000 reported a correlation between changes in funding, per capita cigarette consumption and mortality from heart disease in California during the 1990s, and estimated that over the first eight years of the campaign 33,000 deaths from heart disease were avoided. Goldman and colleagues calculated that a decline of 12.2% following the second wave of media activity could be directly attributed to the campaign rather than to fiscal pressures (California TCP 2003). In Massachusetts the programme budget was also cut. Friend 2002 notes that the gradual tapering off of the effectiveness of the California and Massachusetts campaigns may be an inevitable reduction in impact over time, irrespective of fluctuating trends in funding.

The impact of campaign duration and intensity is difficult to ascertain. The Flay 1987b and Friend 2002 reviews both detected an effect of longer duration and higher intensity campaigns, but our own assessment has less clearcut findings. McVey 2000, comparing the impact of single‐ and double‐weight TV campaigns on quit rates, found no significant differences at six months, with the single‐weight region (Granada) at 6.3% and double‐weight (Tyne Tees, Yorkshire) at 6.6%, yielding an adjusted OR of 1.02 (P = 0.94). The Vietnamese‒American men studies I (McPhee 1995) and II (Jenkins 1997) ran for a total of 24 and 39 months respectively, with the latter producing positive effects, but other factors in the study design (a 15‐month pilot phase, physician input, Saturday schools, student and family involvement) may have confounded the mass media effect. North Coast QFL 1983 lasted for three years, but after early success the campaign was scaled down and prevalence rose again during the second year; the intervention effects may have been masked by a concurrent substantial decline in smoking in the control community. In the Stanford 3 City 1977 study, it is difficult to disentangle the effects of the mass media campaign from face‐to‐face counselling in the intervention communities. However, significant declines in cigarette consumption were observed only within the community in which the whole population was exposed to a mass media campaign with high‐risk smokers receiving intensive counselling, and not in the community that received the media campaign alone. In the Sydney QFL 1986 study, a significant decline in smoking prevalence was observed in the intervention city at the end of the first year, but from that point on both cities (Sydney and Melbourne) over four years received complex interventions which included mass media campaigns. It was not possible to separate out the independent effect of the mass media from co‐interventions such as physician input, smoking clinics, school programmes and shopping mall displays. From the studies in our review, there was no consistent relationship discernible between campaign duration and effectiveness.

Differences by age, gender, ethnicity and education presented similar problems. During the assessment period (1989 to 2000) for the California TCP 2003, the decline was significant for women but not for men during the last phase only. The trend was significant for older smokers (45+) throughout the campaign. Changes in male smoking prevalence were similar between ethnic groups, with the highest smoking prevalence reported in African Americans. In women, significant declines in prevalence were observed for Hispanic and non‐Hispanic white women. The greatest decline in male smoking prevalence was observed for college graduates, while in women the largest declines were noted in those who did not graduate from high school. In the Massachusetts campaign, the decline in smoking prevalence between 1990 and 2000 was significantly different from the rest of the USA for men but not for women. The effect was also more pronounced for people aged between 18 and 34, for those who graduated from high school but not college, and for white non‐Hispanics.

After four years' follow‐up CORIS 1997 detected significantly higher quit rates for women than for men, but after 12 years this difference was no longer apparent, with prevalence for men significantly lower in the intervention than in the control community, but not for women. The North Coast QFL 1983 study found no difference between men and women, but a significant trend by age, with greater declines in prevalence among younger smokers. The Sydney QFL 1986 study detected no significant associations between changes in prevalence and demographic characteristics, other than a long‐term decline in prevalence for men but not for women. The impact of age was contradictory, with three campaigns detecting positive effects among older smokers, and three among younger smokers (up to 34 years).

Gender indications were also inconclusive, with three studies showing positive long‐term effects for men, and one for women. This mixed picture casts doubt upon the widely‐held assumption that targeted campaigns are likely to be the most effective. Chapman 2007 points out that the tobacco industry, although nuancing much of its promotion to appeal to different subgroups within a population, does not tailor its packaging or advertising of the major brands (e.g. Camel, Marlboro) to different cultural groups or countries.

Quality of the evidence

Overall the included studies were assessed as being at high risk of bias. All the included studies used some kind of control group, but did not randomise communities to intervention and control conditions. Baseline demographic characteristics were statistically compared in five studies (three with positive outcomes and two with a negative outcome). Studies with declared baseline differences between compared groups controlled for those differences in the analyses. Six studies did not conduct statistical tests for comparability between groups or did not describe details of demographic characteristics of the population. Since comparison groups were not randomised, there could be baseline differences between them which could have confounded the results.

Most of the studies with positive findings had problems with drop‐outs and missing data. Response rates ranged from 42.7% to 99.4%, with retention rates between 52% and 76%. Most studies with positive findings did not provide information on participants lost to follow‐up. Any of these limitations could have confounded the results of the studies.

Analysis 1.5 gives information on those studies which identified possible confounders, the analytical measures taken to control for these, and the changes in effect where reported.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There is a broad consensus that comprehensive tobacco control interventions which include mass media campaigns can be effective in reducing smoking consumption and prevalence (Flay 1987a; Flay 1987b; COMMIT 1995; Levy 2000; Friend 2002; Biener 2006; NICE 2007; NCI 2008; Niederdeppe 2008; Ontario 2009; Durkin 2012; Wilson 2012).

The NICE 2007 review found little high‐quality evidence for the effectiveness of targeting mass media interventions at high‐risk groups such as pregnant women, men only or young smokers.

Durkin 2012 assessed mass media interventions in adults on the basis of 26 population‐based studies (cohort, cross‐sectional and time series, with no control group). They concluded that the evidence supports the use of mass media campaigns as a part of comprehensive tobacco control programmes. In addition the authors evaluated different message types and different media channels using subgroup analysis.

NCI 2008 reported on the role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. They included studies of various designs, and concluded that mass media campaigns may encourage adult smoking cessation and lead to decreases in smoking prevalence.

Niederdeppe 2008 conducted a systematic review of the effectiveness of media campaigns in smoking cessation in socio‐economically disadvantaged populations. They included 50 studies, and concluded that media campaigns are less or equally effective in populations with low socio‐economic status compared with populations with higher socio‐economic status. In addition they observed that media campaigns in disadvantaged populations are most effective when combined with tobacco control programmes.

The Ontario 2009 Health Technology Assessment report examined the efficacy and cost effectiveness of selected population‐based interventions for smoking cessation, including mass media interventions; they agreed with the conclusions of our review.

Wilson 2012 evaluated several tobacco control interventions outlined in the WHO MPOWER Package, including mass media interventions in adults and youth. They included 19 studies with and without control groups, some of which were also included in our review, but excluded studies assessing multi‐component interventions. They concluded that there is moderate evidence that mass media can be effective in reducing smoking prevalence in adults.

Atusingwize 2015 conducted a review of economic evaluations of tobacco control mass media interventions. They noted methodological and content heterogeneity and limitations, but despite this, found consistent evidence that these campaigns were cost‐effective.

As a part of Community Preventive Services Task Force, Robinson 2014, reviewed the effectiveness of mass media health communication campaigns. Some of these were campaigns on smoking but that also included distributing smoking cessation materials and aids. Twenty two studies were included and from these they concluded that mass media‐supported distribution of cessation aids improves smoking cessation.

Prisma flow diagram of search results

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

| Study | Design | Intervention | Control |

| California TCP 2003 | Nested cross‐sectional | 1990‐1 75.1%1 (CA only) | NHIS, BRFSS and CPS rates apply. |

| CORIS 1997 | Nested cross‐sectional | 69.5% at baseline, 67.5% at resurvey | 64% at baseline, 63% at resurvey |

| Jenkins 1997 | Nested cross‐sectional | Pretest: 84%, post‐test: 94% | Pretest: 82%, post‐test: 88% |

| Massachusetts 2003 | Nested cross‐sectional | Median (1995): 60.4%, median (1999): 42.7%6 | Median (1995): 68.4%, median (1999): 55.2% |

| McAlister 2004 | Nested cross‐sectional | Baseline survey 9407, 7m follow‐up 8974; response rate approximately 60%. | Not reported separately |

| McPhee 1995 | Nested cross‐sectional | Pretest: 81%, post‐test: 82% | Pretest: 85%, post‐test: 88% |

| McVey 2000 | Nested cohort | Smokers: 6m: 73%, 18m: 70% | Smokers: 6m: 74%, 18m: 66% |

| Mogielnicki 1986 | Randomized cohort | Mail: Yr2 follow‐up: 17% | Mail: Yr2 follow‐up: 15% |

| North Coast QFL 1983 | Nested cross‐sectional | Baseline: 71% | Baseline: 72% |

| Stanford 3 City 1977 | Nested cross‐sectional | Gilroy 116 at baseline. | Tracy 115 at baseline. |

| Sydney QFL 1986 | Nested cross‐sectional | Sydney: 66% | Australia‐wide: 60% |

Comparison 1 Mass media versus no mass media, Outcome 1 Response and retention rates.

| Study | Intermediate measure | Process measures |

| California TCP 2003 | Between 1996 and 1999 slight increases in agreements that smoking causes cancer (82.2% and 83.3%) and that passive smoking harms children's health (93.2% and 94%). Between 1992 and 2002 increases in agreement that passive smoking causes cancer in nonsmokers (1992: 62.4%, 1996: 66.8%, 1999: 68.9%, 2002: 72.1%) and that smoking harms children's health (1992: 85.5%, 1996: 87.7%, 1999: 90.1%, 2002: 90.9%). In 2008, 67.2% of daily smokers, 80.2% of non‐daily smokers, and 85.8% of nonsmokers perceived secondhand smoke (SHS) as a cause of cancer and 88.6% of daily smokers, 94.1% of non‐daily smokers and 94.7% of non‐smokers believed that SHS can harm the health of children and babies. Further increase in % of smokers thinking about quitting between 1994 and 2005, in the next 30 days (1994: 30.9, 2000:37.8%, 2005: 43.9%) and in the next 6 months (1994: 65.6%, 2000: 74%, 2005: 75%). In 2008, 95.2% of smokers and 96.6% of nonsmokers report having a completely smoke‐free workplace. Between 1992 and 2008 increase in % of homes with smoking ban (1992: 48.1, 1993: 50.9%, 1996: 64.5%, 1999: 72.8%, 2002: 76.9%, 2005: 78.4%, 2008: 80.8%). Between 1992 and 2008 increase in % of smokers with a total home ban on smoking (1992: 19.4 ± 1.6%, 2008: 59.3 ± 2.6%; increase of 204.9%). Between 1990 and 2008 decrease in % of nonsmokers exposed to ETS at work (1990: 29%, 1993: 22.4%, 1996: 11.8%, 1999: 15.6%, 2002: 12.0%, 2005: 13.9%, 2008: 13.5%). Increases in: support for further increase in tax on tobacco (1992: 74%, 1993: 78%; 2008: 78%), support for ban on tobacco advertising (1990: 52%, 1996: 65% [read from the graph]), support for ban on tobacco sponsorships (1998: 56%, 2000: 60%), % of adults preferring non‐smoking bars (1996: 75%, 2000: 81%), support for banning smoking outside the entrance of buildings (2002: 62.8%, 2008: 72.1%) and in restaurant outdoor patios (2002: 62.4%, 2008: 75%), outdoor public places (2002: 52.3%, 2008: 60.4%), Indian casinos (2002: 59.9%, 2008: 66.5%), inside cars when children are in them (2005: 92.3%, 2008: 95.2%). | Systematic monitoring of the campaign and independent evaluations of the programme. Media weight: 1990/1: 50+ TV spots, 50 radio spots (69 radio stations), 20 outdoor ads (775 outdoor venues), 40 newspaper ads (130 newspapers); 1992/3: 40 spots (20 TV, 12 radio, 8 in outdoor locations), 44% focused on reducing ETS, 34% on countering pro‐tobacco influences, 20% smoking cessation and 2% on reducing youth access. 1990/4: local health departments conducted 10,000+ multi‐session programmes focusing on prevention (61%), cessation (37%) and ETS (2%). July 1995 ‐ Dec 1996: 19 ads (11 TV, 4 radio, 4 outdoor); 1997 ‐ 1998: 40 general audience ads for distribution (20 TV, 12 radio, 8 outdoor); July 1998 ‐ Aug 1999: 50 general audience anti‐tobacco ads (22 TV, 13 radio, 15 print ‐ mostly billboards). In 1996, 67% of adults reported seeing antismoking message on TV, 44% hearing on radio, 41% seeing antismoking billboard. In 1998 80% of adults were exposed to tobacco control programme through two or more components. In 2011 in CSC 28% to 61% recalled anti‐tobacco commercials. 2011 recall of any of anti‐tobacco spots was not related to quitting 1 yr later, recall of one specific spot ("Stages") was associated with higher quit attempts rate and quitting for more than 1 month, after 1 yr. The analysis on the basis of per capita consumption of cigarettes and average per capita media expenditures gave estimates of a fall of 3.9 packs per capita per year for each per capita USD spent on the media campaign. |

| CORIS 1997 | At baseline, knowledge scores higher in Swellenden than in Riversdale (both cross‐sectional and cohort surveys; no statistical comparisons given); at 4 yrs more increase in women in Swellenden (both cross‐sectional and cohort surveys; in cohort survey net change statistically significant); at 12 yrs increase in both communities and no difference. | Participation and reach of activities recorded in mass media and community intervention town (not included in this analysis). Media weight: Limited data. 1st yr: 6 different billboards, 6 posters, 8 mailings, frequent news items, health messages on electricity accounts, 1 special supplement in local newspaper. 2nd and 3rd yr frequency of billboards, posters and mailings about half of the initial rate, but news items frequent and annual special supplement in a local newspaper was added. Intervention costs: per capita costs given (USD 5 over 4 yrs in intervention community). |

| Jenkins 1997 | At baseline no differences in motivation to quit and self efficacy (SF/Houston: 29%/23%; 29%/25%). At follow‐up significant increase in motivation in both communities, but no difference (SF/Houston: 45%/ 44%), no significant change in self efficacy (SF/Houston: 33%/26%). | A 15‐month uncontrolled pilot anti‐tobacco campaign. Maintenance: no evidence found. Intervention costs: no evidence found. |

| Massachusetts 2003 | 1993 ‐ 2000: the majority of non‐smokers believed that second‐hand smoke (SHS) can harm children (96%) and can cause lung cancer (89%); increase in % of smokers believing that environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) can harm their children (1993: 78%, 1999: 91%, 2000: 93%) and can cause cancer (1993: 58%, 1999: 72%, 2000: 74%); 2007 ‐ 94.5% believe ETS is harmful. Decrease in: ETS exposure at work (1993: 44%, 2000: 29%), at home (1993: 28%, 2000: 18%) and in restaurants (1995: 64%, 2000: 39%, 2002: 37%), mean hours of ETS exposure during prior week at work (1993: 4.2, 1995: 2.3, P < 0.05, 1997: 2.2, 2001: 1.4), and at home (1993: 4.7, 2000: 3.3). Increase in: % of population covered by smoking restrictions in restaurants (1995: 26%, 2000: 69%, 2001: 78%); % of population living in a town with some form of smoking restrictions in public places (1993: 22%, 2000: 78%, 2001: 85%); % of smokers reporting that fewer than half their friends and relatives smoke (1993: 40.8%, 2000: 46.9%; P for trend = 0.03); most non‐smokers reported so both in 1993 and 2000 (1993: 90.1, 2000: 89.9). 2008 ‐ 80.7% voluntary tobacco‐free homes (vs 81.5% in 2007). 2009‐ 57% of schools with comprehensive smoking policies 2014 ‐ based BRFSS exposure for ETS decreased to 10% (vs 32% in 2002); only 16.4% of houses allow smoking. and exposure to ETS >1 hr/last wk decreased to 11% (vs 32% in 2002; 14.5% in 2008). Increase in support smoking ban in all personal spaces ‐ of people living in smoke‐free houses 87% and of those living in non smoke‐free houses 52%. | Messages were developed through formative research including focus groups. Systematic evaluation of the programme. Media weight: Oct 1993 ‐ Dec 1996: 66 spots aired; 35 TV ads (14,901 total gross rating points [GRP]), 27 radio spots (13,644 total GRP) on smoking cessation in adults; 38 TV (17,800 total GRP) and 22 radio (13,950 total GRP) ads targeted youth; 6 TV (17,727 total GRP) and 2 radio spots (6,308 total GRP) on ETS. Awareness/reach: 88% respondents saw any TV ads, among quitters ‐ 97%. On average 4.48 ads recognised. In 1995, 65% of the adult population were aware of the statewide anti‐tobacco campaign, and 76% recognised the tag line of the media campaign "It's time we made smoking history". Around 89% of adult smokers reported having heard, read or seen information about quitting smoking within the past year. Dose‐response: no evidence found. Maintenance: The campaign is ongoing. Intervention costs: On average USD13 million per year spent on anti‐tobacco advertising. About 48% expenditure (up to Dec 1996) spent on TV time (much prime time viewing hours). MTCP activities expenditures: 1st yr ‐ USD 43 million, 3rd yr ‐ USD 35 million. Mean per capita cost for media campaign was USD 2.42. |