Trabeculoplastia laser para el glaucoma de ángulo abierto

Referencias

Referencias de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios excluidos de esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios en espera de evaluación

Referencias adicionales

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, centralised, stratified list generated by a formal procedure, assigned the eye to one of the two surgical sequences. Both eyes could be enrolled if they both met inclusion criteria at the same time and they were randomised separately | |

| Participants | N = 591 participants (789 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT + trabeculectomy + trabeculectomy (n = 404) | |

| Outcomes | Early failure (6 weeks): IOP > initial levels, SVFD | |

| Notes | Considering this study has three interventions in each group, we will consider the results just of the first intervention, which were obtained by personal contact | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised | |

| Participants | N = 82 participants (82 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT (n = 40). 2 sessions 1 month apart (randomly assigned superiorly or inferiorly). 50 spots, 50 micra, 0.1 seconds. No postoperative steroids were used | |

| Outcomes | Failure: | |

| Notes | 1 participant deceased after 10 months of treatment | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (table of random numbers) | |

| Participants | N = 40 participants (40 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. DLT (n = 20) | |

| Outcomes | Failure: | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised | |

| Participants | N = 20 participants | |

| Interventions | 1. DLT (n =10) | |

| Outcomes | Failure: less of 20% IOP reduction or need of changing in medication | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, by a third person, random numbers table. If the patient had both eyes to be treated they were randomised separately. | |

| Participants | N = 46 participants (50 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. DLT (n = 22) | |

| Outcomes | Failure: need of trabeculectomy | |

| Notes | No difference of IOP between groups at any time. 4 participants had both eyes randomised | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised by a blocked randomisation schedule (computered generated), third party | |

| Participants | N = 152 participants (176 eyes). Both eyes included but correlation between eyes was accounted. | |

| Interventions | 1. SLT (n = 89) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: less of 20% IOP reduction from initial values at 6 months and one year. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, methods not specified. When both eye were eligible, one eye was randomised to each group | |

| Participants | N = 34 participants (40 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT in 2 stages. Treatment of 180 degrees of trabecular meshwork in each stage (n = 19) | |

| Outcomes | Failure: | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (set of sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes provided by a Data centre) | |

| Participants | N = 255 participants (if possible both eyes with correction of correlation between fellow eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. No treatment (n = 126) | |

| Outcomes | Primary: glaucoma progression (visual field changes or optic disk changes). Visual field progression was defined as worsening of 3 consecutive points in the Glaucoma Change Probability map, confirmed in 3 consecutive visual fields. Optic disc progression should be detected by a masking reader in a flicker chronoscopy and side by side comparison in 2 consecutive visits | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, methods not specified | |

| Participants | N = 32 participants randomised. | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT (n = 16) | |

| Outcomes | Primary: change in the PC20, the provocative concentration that reduced at least 20% of the forced expirated volume, presented in a logarithmic transformed value | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised. Blocked on patient: 1 eye 1 intervention, fellow eye the other | |

| Participants | N = 271 participants (542 eyes). At follow up (after 2 years) 203 participants were followed. | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT first followed by topical medication if needed (n = 271) | |

| Outcomes | Failure criteria: | |

| Notes | At 2 years of follow up uncontrolled IOP was defined as need of one medication to the LF group and add a second medication to MF group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (not mentioned allocation criteria, but were stratified by race before randomisation) | |

| Participants | N = 36 participants (45 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT (100 burns, applied 360 degrees over the meshwork) (n = 15) | |

| Outcomes | Failure criteria: further intervention required (after completion of 100 burns of ALT) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised | |

| Participants | N = 80 participants (102 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT receiving 50 burns to the superior 180 degrees of the trabecular meshwork (n = 49 eyes) | |

| Outcomes | Failure criteria: further intervention required (either completion of ALT or filtration surgery) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (one eye allocated to receive treatment with 0.2s and the fellow eye received 0.1s) | |

| Participants | N= 33 participants randomised (64 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT with duration of 0.1 sec in OD and with 0.3 seconds each spot in OS (n=17) | |

| Outcomes | Failure criteria: Adverse effects: IOP spikes after one hour of laser application | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (computer selection) | |

| Participants | N = 77 participants randomised (44 participants with a minimum of six months of follow up were analysed) | |

| Interventions | 1. Medical treatment (pilocarpine and/or sympatomimetics and/or timolol and/or carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (n = 15). Medical regimen could have been changed to control IOP. n2 (post publication) = 56 | |

| Outcomes | Failure criteria: IOP equal or greater than 22 mmHg after 3 months of treatment or visual field loss greater than 2% per annum | |

| Notes | If failure occurred the second line treatment was undertaken and again randomly allocated | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised | |

| Participants | N = 30 participants (48 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT (n = 25 eyes). Technique: 50 micra in the anterior portion of the trabecular meshwork, 0.1 sec of duration, power was adjusted to 800 to 1000mW. 50 burns placed over nasal 180 degrees at first application. If after 3 months the IOP remained high the procedure was repeated at the 180 degrees temporally. Eyes received prednisolone acetate 1% if there was uveitis | |

| Outcomes | Success criteria: successful control: IOP < 22 mmHg | |

| Notes | The authors describe the results of each success group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (each eye). Methods of allocation: picking from a hat | |

| Participants | N = 120 participants | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT (n = 29), 50 micra, 0.1 sec, power level 500 mW | |

| Outcomes | Failure criteria: | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (one eye selected by computer, the other eye selected as control) | |

| Participants | N = 25 participants (50 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT (n = 25) (360 degrees, 100 burns, 0.1 seconds, 150 to 350 micra size spots) continued with maximal medical therapy. The participants received topical prednisolone 1% 4 times a day for one week after the treatment | |

| Outcomes | Success criteria: IOP decrease of 20% or more from the baseline examination; no IOP readings above 21 mmHg; stable visual fields by Goldmann perimetry | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised | |

| Participants | N = 100 participants (100 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. Bichromatic wavelength (blue‐green) ALT, performed with 80 burns over 360 degrees of the anterior portion of the trabecular meshwork (n = 50 eyes) | |

| Outcomes | Failure: need for filtering surgery | |

| Notes | Green manufactured by MIRA; Blue‐green manufactured by Coherent Radiation Model 900 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised (blocked, by a third party not involved). If a participant required a second eye to be treated this was subjected to the same randomisation procedure as the first | |

| Participants | N = 61 participants (95 eyes) | |

| Interventions | 1. ALT (n = 46). Blue/green laser source, applied 180 degrees of the trabecular meshwork, 50 burns, 50 micra spots | |

| Outcomes | Continuous data; need for medication; need for filtering surgery | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

ALT: argon laser trabeculoplasty

COAG: chronic open angle glaucoma

DLT: diode laser trabeculoplasty

IOP: intraocular pressure

ITT: intention‐to‐treat

MMT: maximal medical therapy

NTG: normal tension glaucoma

OAG: open angle glaucoma

PAS: peripheral anterior synechiae

POAG: primary open angle glaucoma

SVFD: sustained visual field defect

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Ir a:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Allocation: peudo randomisation | |

| Outcome: continuous intraocular pressure | |

| Interventions: Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus vascular medication | |

| Follow up: 6 weeks | |

| Follow up: 3 months | |

| Outcome: continuous intraocular pressure | |

| Allocation: pseudo randomisation | |

| Allocation: (pseudorandomisation) right eye of each participant received argon laser trabeculoplasty and left eye received Q‐switched Nd:Yag laser trabeculoplasty (non‐randomised) | |

| Follow up: 24 hours | |

| Participants: people with primary open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension | |

| Follow up: 8 weeks | |

| Participants: people with primary open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension | |

| Follow up: 3 months | |

| Follow up: 35 days | |

| Follow up: 16 weeks | |

| Allocation: pseudorandomisation (participants born in even years received medication and participants born in odd years received argon laser trabeculoplasty) | |

| Follow up: 24 hours | |

| Follow up: 2 months |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Failure to control IOP Show forest plot | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

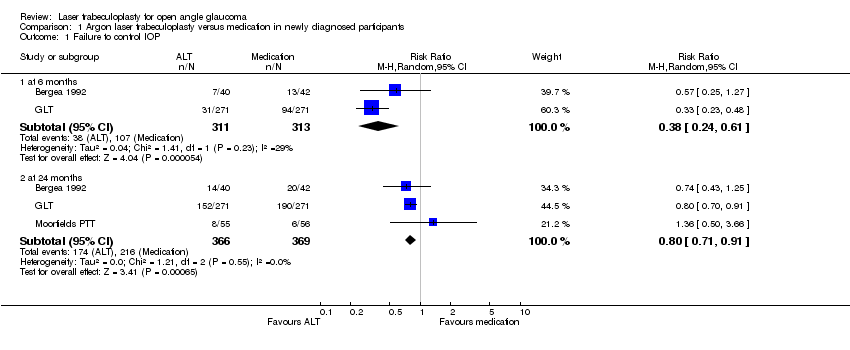

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus medication in newly diagnosed participants, Outcome 1 Failure to control IOP. | ||||

| 1.1 at 6 months | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.24, 0.61] |

| 1.2 at 24 months | 3 | 735 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.71, 0.91] |

| 2 Visual field progression Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus medication in newly diagnosed participants, Outcome 2 Visual field progression. | ||||

| 2.1 at 24 months | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.42, 1.16] |

| 3 Optic neuropathy progression Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus medication in newly diagnosed participants, Outcome 3 Optic neuropathy progression. | ||||

| 3.1 at 24 months | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.38, 1.34] |

| 4 Adverse effects: PAS formation Show forest plot | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 11.15 [5.63, 22.09] |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus medication in newly diagnosed participants, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: PAS formation. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Failure to control IOP Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

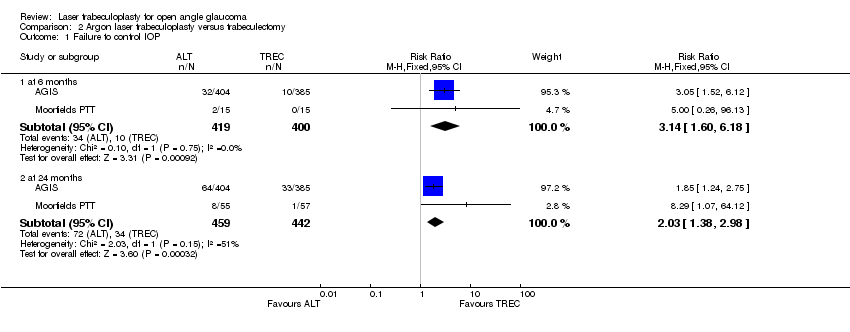

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus trabeculectomy, Outcome 1 Failure to control IOP. | ||||

| 1.1 at 6 months | 2 | 819 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.14 [1.60, 6.18] |

| 1.2 at 24 months | 2 | 901 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [1.38, 2.98] |

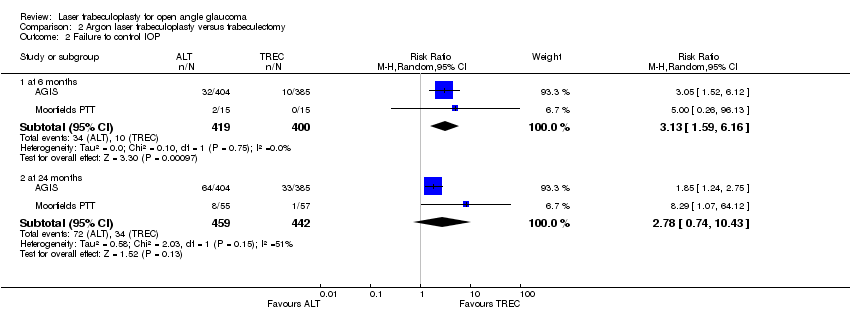

| 2 Failure to control IOP Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.2  Comparison 2 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus trabeculectomy, Outcome 2 Failure to control IOP. | ||||

| 2.1 at 6 months | 2 | 819 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.13 [1.59, 6.16] |

| 2.2 at 24 months | 2 | 901 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.78 [0.74, 10.43] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Adverse effects: early intraocular pressure spikes Show forest plot | 3 | 110 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.21, 2.14] |

| Analysis 3.1  Comparison 3 Diode laser trabeculoplasty versus argon laser trabeculoplasty, Outcome 1 Adverse effects: early intraocular pressure spikes. | ||||

Comparison 1 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus medication in newly diagnosed participants, Outcome 1 Failure to control IOP.

Comparison 1 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus medication in newly diagnosed participants, Outcome 2 Visual field progression.

Comparison 1 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus medication in newly diagnosed participants, Outcome 3 Optic neuropathy progression.

Comparison 1 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus medication in newly diagnosed participants, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: PAS formation.

Comparison 2 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus trabeculectomy, Outcome 1 Failure to control IOP.

Comparison 2 Argon laser trabeculoplasty versus trabeculectomy, Outcome 2 Failure to control IOP.

Comparison 3 Diode laser trabeculoplasty versus argon laser trabeculoplasty, Outcome 1 Adverse effects: early intraocular pressure spikes.

| TRIAL | Selection bias | Performance bias | Detection bias | Attrition bias |

| A | D | A | A | |

| A | D | A | A | |

| B | D | B | A | |

| B | D | A | A | |

| A | D | B | A | |

| A | D | B | A | |

| B | D | B | B | |

| A | D | A | A | |

| B | D | B | A | |

| A | D | A | A | |

| B | D | C | C | |

| B | D | C | C | |

| B | D | A | C | |

| A | D | A | B | |

| B | D | C | A | |

| A | D | C | B | |

| A | D | A | A | |

| B | D | B | B | |

| A | D | C | C |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Failure to control IOP Show forest plot | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 at 6 months | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.24, 0.61] |

| 1.2 at 24 months | 3 | 735 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.71, 0.91] |

| 2 Visual field progression Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 at 24 months | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.42, 1.16] |

| 3 Optic neuropathy progression Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 at 24 months | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.38, 1.34] |

| 4 Adverse effects: PAS formation Show forest plot | 2 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 11.15 [5.63, 22.09] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Failure to control IOP Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 at 6 months | 2 | 819 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.14 [1.60, 6.18] |

| 1.2 at 24 months | 2 | 901 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [1.38, 2.98] |

| 2 Failure to control IOP Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 at 6 months | 2 | 819 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.13 [1.59, 6.16] |

| 2.2 at 24 months | 2 | 901 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.78 [0.74, 10.43] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Adverse effects: early intraocular pressure spikes Show forest plot | 3 | 110 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.21, 2.14] |