Tratamiento farmacológico y nutricional para la enfermedad de McArdle (enfermedad por almacenamiento de glucógeno tipo V)

Resumen

Antecedentes

La enfermedad de McArdle (Enfermedad del Almacenamiento de Glucógeno tipo V) es causada por la ausencia de fosforilasa muscular que provoca intolerancia al ejercicio, rabdomiolisis por mioglobinuria e insuficiencia renal aguda. Ésta es una actualización de una revisión publicada por primera vez en 2004.

Objetivos

Revisar sistemáticamente la evidencia de los ensayos controlados aleatorizados (ECA) de los tratamientos farmacológicos o nutricionales para mejorar el rendimiento del ejercicio y la calidad de vida en la enfermedad de McArdle.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se realizaron búsquedas en el Registro Especializado del Grupo Cochrane de Enfermedades Neuromusculares (Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Group), CENTRAL, MEDLINE y EMBASE el 11 de agosto de 2014.

Criterios de selección

Se incluyeron ECA (incluyendo estudios cruzados [cross‐over]) y cuasi ECA. Se incluyeron en la discusión ensayos abiertos sin cegamiento y estudios de pacientes individuales. Las intervenciones incluían cualquier agente farmacológico o suplemento nutricional. Las medidas de resultado primarias incluían cualquier evaluación objetiva de la resistencia al ejercicio (por ejemplo, la capacidad aeróbica (VO2) máxima, la velocidad al caminar, la fuerza o la potencia muscular y la fatigabilidad). Las medidas de resultado secundarias incluían cambios metabólicos (como reducción de la creatinquinasa en plasma y reducción de la frecuencia de mioglobinuria), las medidas subjetivas (incluida las puntuaciones de la calidad de vida y los índices de discapacidad) y los eventos adversos graves.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Tres autores de la revisión verificaron los títulos y los resúmenes identificados mediante la búsqueda y revisaron los manuscritos. Dos autores de la revisión evaluaron de forma independiente el riesgo de sesgo de los estudios pertinentes, con comentarios de un tercer autor. Dos autores extrajeron los datos en un formulario especialmente diseñado.

Resultados principales

Se identificaron 31 estudios y 13 cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. Se describieron los ensayos que no fueron elegibles para la revisión en la Discusión. Los estudios incluidos comprendían un total de 85 participantes, pero el número en cada ensayo individual era pequeño; el ensayo de tratamiento más grande incluía a 19 participantes y el estudio más pequeño incluía sólo a un participante. No hubo ningún beneficio con: D‐ribosa, glucagón, verapamilo, vitamina B6, aminoácidos orales de cadena ramificada, dantroleno sódico, creatina en alta dosis y ramipril. Se encontró un beneficio subjetivo mínimo con una dosis baja de creatina y ramipril sólo para los pacientes con un polimorfismo conocido como el fenotipo de la enzima convertidora de angiotensina (ECA) D/D. Una dieta rica en carbohidratos dio como resultado un mejor rendimiento en el ejercicio en comparación con una dieta rica en proteínas. Dos estudios de la sacarosa oral administrada en diferentes momentos y en diferentes cantidades antes del ejercicio mostraron una mejora en el rendimiento del ejercicio. Cuatro estudios informaron efectos adversos. La ribosa oral causaba diarrea y síntomas que sugerían hipoglucemia, como mareos ligeros y hambre. En un estudio, los aminoácidos de cadena ramificada causaron un deterioro de los resultados funcionales. Se informó de que el dantroleno causaba varios efectos adversos, como cansancio, somnolencia, mareos y debilidad muscular. La creatina en dosis bajas (60 mg/kg/día) no causó efectos secundarios, pero la creatina en dosis altas (150 mg/kg/día) empeoró los síntomas de la mialgia.

Conclusiones de los autores

Aunque hubo evidencia de baja calidad de la mejora de algunos parámetros con la creatina, la sacarosa oral, el ramipril y una dieta rica en carbohidratos, ninguna fue lo suficientemente fuerte como para indicar un beneficio clínico significativo.

PICO

Resumen en términos sencillos

Tratamiento farmacológico y nutricional para la enfermedad de McArdle

Pregunta de la revisión

Se revisó la evidencia sobre los efectos de los tratamientos farmacológicos y nutricionales para la enfermedad de McArdle.

Antecedentes

La enfermedad de McArdle (también conocida como enfermedad de almacenamiento de glucógeno tipo V) es un trastorno que afecta al metabolismo muscular. La condición es causada por la falta de una enzima llamada fosforilasa muscular. Esto resulta en una incapacidad de descomponer los almacenes de "combustible" de glucógeno. La enfermedad de McArdle provoca dolor y fatiga con el ejercicio vigoroso. A veces, se desarrolla un daño muscular severo y ocasionalmente esto resulta en una insuficiencia renal reversible aguda.

Características de los estudios

Después de una amplia búsqueda, se identificaron 13 estudios aleatorizados que incluían a 85 participantes con la enfermedad de McArdle. Ésta es una actualización de una revisión publicada por primera vez en 2004. No se encontraron nuevos ensayos en esta actualización.

Resultados clave y calidad de la evidencia

La revisión no encontró ningún beneficio en comparación con el placebo con los siguientes tratamientos: D‐ribosa, glucagón, verapamilo, vitamina B6, aminoácidos orales de cadena ramificada, dantroleno sódico, creatina en alta dosis y ramipril. La creatina y el ramipril en dosis bajas produjeron un beneficio mínimo para los pacientes que también tienen el fenotipo de la enzima convertidora de angiotensina D/D (ECA). Tomar suplementos de creatina en dosis bajas tuvo un beneficio menor al mejorar la tolerancia al ejercicio en un pequeño número de pacientes con la enfermedad. Tomar una bebida azucarada antes del ejercicio vigoroso planificado puede mejorar el rendimiento, pero este tratamiento no es práctico para la vida diaria. Una dieta rica en hidratos de carbono puede ser más beneficiosa que una dieta rica en proteínas. En cuatro estudios se informaron los efectos adversos. La ribosa oral causaba síntomas que sugerían un bajo nivel de azúcar en la sangre, como mareos, hambre y diarrea. Un estudio de aminoácidos de cadena ramificada resultó en un deterioro de los participantes. Se informó de que el dantroleno causaba una serie de efectos secundarios como cansancio, somnolencia, mareos y debilidad muscular. La creatina en dosis bajas (60 mg/kg/día) no causó ningún efecto secundario, pero la creatina en dosis altas (150 mg/kg/día) empeoró los síntomas de dolor muscular. La calidad de estos estudios fue baja debido al reducido número de participantes; el mayor número de un ensayo fue 19 y uno de ellos tuvo sólo un participante.

La evidencia está actualizada hasta agosto de 2014.

Authors' conclusions

Background

McArdle disease (glycogen storage disease type V) is a disorder of muscle metabolism caused by the absence of the glycolytic enzyme, muscle phosphorylase. The first patient, described by Brian McArdle (McArdle 1951), presented with exercise‐induced myalgia and failed to produce a rise in blood lactate during ischaemic forearm exercise. In 1959 muscle phosphorylase was discovered and subsequently its deficiency confirmed in McArdle disease (Mommaerts 1959; Schmidt 1959). There is no detectable muscle glycogen phosphorylase activity in the majority of affected individuals. However in a small number, the levels of this enzyme are reduced (20% to 30% of normal values) but not absent (Beynon 1995).

The inheritance of McArdle disease is autosomal recessive and heterozygotes are usually asymptomatic. The muscle phosphorylase gene is located at 11q13 and spans 20 exons (Bartram 1993). The most common mutation in Northern European and North American people is the nonsense mutation at R50X (previously referred to as R49X) (Kubisch 1998). Many different mutations in the gene have been identified (Andreu 2007). The preferred method of diagnosis is by muscle histochemistry following muscle biopsy.

The consequence of muscle phosphorylase deficiency is the inability to mobilise muscle glycogen stores during anaerobic metabolism. To exacerbate the situation in McArdle disease, oxidative phosphorylation is also impaired because of an abnormally low substrate flux through the tricarboxylic acid cycle. This is most likely the result of virtual absence of pyruvate from glycolysis. This reduces the rate of acetyl‐Co enzyme A formation, which in turn affects the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Acetyl‐Co enzyme A can be generated from the breakdown of fatty acids, but without training, most individuals will have limited capacity for fatty acid oxidation during exercise (De Stefano 1996; Ruff 1998). The effect of this decline in oxidative phosphorylation is a decrease in oxygen consumption in affected individuals to 35% to 40% of that seen in normal muscle. Two other physiological effects may exacerbate the symptoms. Firstly a reduction in the blood flow of contracting muscle may lead to partial ischaemia (Libonati 1998). Secondly, a disproportionate increase in heart rate and ventilation rate occurs in affected individuals compared with normal controls (Vissing 1998).

Most people present in the second or third decade, although symptoms are often reported retrospectively from childhood. With advancing age, a small proportion of people develop fixed muscle weakness predominantly affecting the shoulder girdle. The main complaints are exercise‐induced myalgia and fatigue. With severe sustained exercise through pain, a muscle contracture will occur and myoglobinuria (excretion of myoglobin, a muscle protein, in the urine causing dark discolouration), with or without acute renal failure, may follow due to acute rhabdomyolysis (breakdown of the muscles). The majority of people learn to manage their condition using an exercise pattern which exploits a phenomenon known as a 'second wind'. In McArdle disease, pain occurs within a few minutes of initiating exercise. However, if at this stage the person rests until the pain subsides there will be a metabolic shift to fatty acid oxidation enabling exercise to continue. This shift in metabolism occurs more effectively in individuals whose muscles have been conditioned through undertaking regular aerobic exercise.

The diagnosis is suspected by the history and the finding of a raised plasma creatine kinase activity. Patients will fail to produce lactate during an ischaemic exercise test, although this test is not specific for the disorder and could potentially cause acute muscle necrosis and compartment syndrome. The definitive diagnosis is made by muscle histochemistry and the finding of absent functional muscle phosphorylase. In some cases DNA analysis for the common mutations can give an unambiguous diagnosis.

There is considerable heterogeneity in the severity of symptoms, even in individuals who possess the same genetic mutation. The exact reasons are unclear, but might include modifying genes such as the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) gene and alpha actinin 3 (ACTN3) (Gomez‐Gallego 2007; Lucia 2007; Martinuzzi 2008), differences in lifestyle including diet, fitness and aerobic capability. A study of 99 Spanish participants found a significant gender effect with females presenting with a significantly more severe phenotype than males (Rubio 2007). Because of the block in glycolytic metabolism, muscle activity occurring after the first few minutes of exercise is highly dependent on alternative energy sources including amino acids and free fatty acids. Research strategies have focused on increasing the availability of these substrates through either supplementation or dietary modification. At least 80% of the total body pool of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) is in skeletal muscle bound to phosphorylase, and in McArdle disease this large pool of vitamin B6 is deficient (Haller 1983). The active form of vitamin B6 is an important co‐factor for a number of enzymes involved in amino acid metabolism. Thus the extra demands placed on alternative fuel sources in McArdle disease may make people more dependent on vitamin B6. Dantrolene sodium is used as a muscle relaxant for spasticity and for the prevention and treatment of malignant hyperthermia. Dantrolene decreases calcium flux from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, impairing the initiation of the excitation‐contraction coupling mechanisms. A positive effect of dantrolene sodium in reducing exertional myalgia was reported in a single McArdle patient (Bertorini 1982). Creatine supplementation may increase the availability of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and has been shown to benefit the exercise capacity of healthy individuals undergoing resistance training (Vandenberghe 1997) and to increase strength in people with mitochondrial myopathies (Tarnopolsky 1997). In McArdle disease magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies during exercise have demonstrated a rapid depletion of phosphocreatine with exercise, so creatine supplementation therefore might be beneficial. Upregulation of oxidative metabolism through diet, drugs or exercise might potentially increase the availability of a second wind. Thus, for example, an intravenous infusion of glucose during exercise enables glycolysis which in turn up‐regulates oxidative phosphorylation (Haller 2002). The efficiency of muscle adaptation to training has been shown to be due to polymorphic variants of ACE. Polymorphisms leading to insertions or deletions (I/D) can affect muscle performance after training. In particular, the I allele which is associated with reduced ACE activity shows improved performance after aerobic training. Carrying the I/D ACE polymorphism affects phenotypic severity in McArdle disease (Gomez‐Gallego 2007; Martinuzzi 2003). The use of pharmacological agents which inhibit ACE might improve performance in McArdle disease.

In most people with McArdle disease, the primary genetic abnormality is a missense mutation in the PYGM gene leading to a stop codon. Certain drugs, for example the aminoglycoside, may allow the potential to read through stop codons and thus may induce the synthesis of a full‐length protein (Barton‐Davis 1999). This potential therapeutic strategy may be exploited with new pharmacological compounds for McArdle disease.

Aerobic exercise, another potential therapeutic option for people with McArdle disease, will not be evaluated in this review as there is a separate Cochrane review on the subject (Quinlivan 2011).

This review was first published in 2004. This most recent update was completed in 2014.

Objectives

To systematically review the evidence from RCTs examining the efficacy of pharmacological or nutritional treatments in improving exercise performance and quality of life in McArdle disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs (including cross‐over studies) and quasi‐RCTs. We included proof of principle physiological studies, open trials and single case studies without participant blinding in the Discussion.

Types of participants

We included males and females, both adults and older children (aged eight years and above) with a confirmed diagnosis based upon muscle histochemistry and/or unambiguous DNA studies.

Types of interventions

We considered any pharmacological agent or micronutrient or macronutrient supplementation.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was level of change, after three months from start of treatment in exercise endurance objectively assessed by, for example VO2 max (aerobic capacity), walking speed, muscle force or power and improvement in fatigability.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures after three months of treatment included:

-

metabolic changes including reductions in serum plasma creatine kinase and frequency of myoglobinuria together with metabolic changes seen on 31phosphorus‐magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P‐MRS);

-

subjective measures including quality of life scores and indices of disability;

-

serious adverse events as measured by mortality and morbidity including adverse drug reactions, weight changes, atypical progression of the disease and poor quality of life scores.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

On 11 August 2014 we searched the Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease (NMD) Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL (2014, Issue 7 in The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE (January 1966 to July 2014) and EMBASE (January 1980 to July 2014). The detailed search strategies are in the appendices: Appendix 1 (MEDLINE), Appendix 2 (EMBASE), Appendix 3 (CENTRAL) and Appendix 4 NMD Register. We identified open trials, single case studies and anecdotal reports retrieved during the main search for possible inclusion in the Discussion. We have also included two unpublished studies conducted by authors of this review in the Results and Discussion.

Searching other resources

We reviewed the bibliographies of the randomised trials identified, contacted the authors and known experts in the field and approached pharmaceutical companies to identify additional published or unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (Rob Beynon (for the original review and earlier updates), RQ and AM) checked titles and abstracts identified and each review author independently assessed the full text of all potentially relevant studies.Two review authors (RQ and AM) independently decided which trials fitted the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Each review author independently extracted data from study reports using pre‐agreed data extraction forms.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (RQ and AM) independently graded risk of bias, with comments from BS. The authors used the 'Risk of bias' tool, described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008, updated Higgins 2011). We aimed to obtain any missing data from the trial authors if needed.

Data synthesis

We did not subdivide the patient cohort into any subcategories. If appropriate data were available from more than one trial with a given intervention, we planned to undertake meta‐analysis using the Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan) software (currently RevMan 2014) to combine risk ratios or difference in means as a mean difference with 95% confidence intervals to provide pooled estimates.

This review has a published protocol (Quinlivan 2002).

Results

Description of studies

The results of the new, current searches were as follows: MEDLINE 82 papers, of which 10 were new, EMBASE 40 papers of which 8 were new, Cochrane Neuromuscular Disease Specialized Register 22, of which 4 were new and CENTRAL 29. Since the last search in May 2010, we identified no new trials.

We assessed 31 studies of which we identified 13 as suitable for inclusion in the review (see Characteristics of included studies). There were no new trials at this update. The 31 studies evaluated the following treatments which showed no benefit: high‐dose oral ribose, fat rich diet, glucagon, verapamil, vitamin B6, high protein diet, branched‐chain amino acid supplementation, dantrolene sodium, high‐dose creatine, intravenous gentamicin, ketogenic diet and intralipid infusion. Treatments which showed some benefit included: low dose creatine, intravenous glucose, oral sucrose, carbohydrate‐rich diet and ramipril. Because of the paucity of high quality studies, we decided to include studies with a treatment duration of less than three months. The excluded studies were either proof of principle studies to determine the physiological effects of specific metabolic fuels, open studies or single patient studies with no observer or participant blinding (these are summarised in Characteristics of excluded studies) and will be discussed further in the Discussion.

Risk of bias in included studies

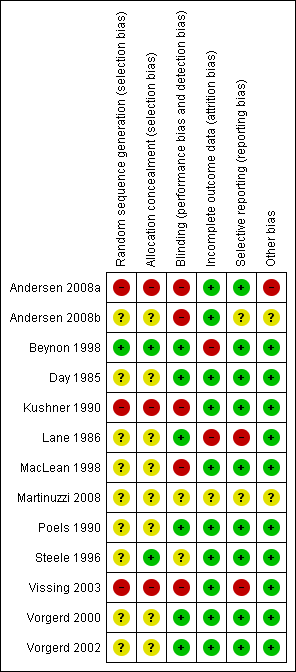

The risk of bias assessment for included studies is summarised in Characteristics of included studies The majority of studies included only a small number of participants or even single cases. There were no studies using the same treatment to allow any formal meta‐analysis to be undertaken, apart from two trials using branched‐chain amino acids and two studies of oral sucrose but with such different regimens as to preclude meta‐analysis. Figure 1 shows a 'Risk of bias' summary with review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. Red (‐) = high risk of bias; yellow (?) = unclear risk of bias, green (+) = low risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

Oral ribose versus placebo

Steele 1996 studied five participants with McArdle disease (four men and one woman, age range 20 to 60 years) in a double‐blind, randomised, controlled cross‐over study of oral ribose solution (15 g D‐ribose made up in 150 mL water taken four times a day for seven days). Baseline measurements were made on no treatment, treatment and placebo. A Borg score for ratings of perceived exertion was used (Borg 1982). Participants underwent a weekly incremental exercise treadmill test with respiratory gas analysis. All five participants completed the trial, although some developed symptoms of hypoglycaemia which included light‐headedness and hunger. One participant developed increased bowel frequency after ribose. Many found the drink too sweet and unpleasant to taste, and this may have compromised concealment. The study failed to show any normalisation of metabolic parameters or improved activity, although there was some normalisation of the ventilatory response to exercise.

Glucagon versus placebo

Day 1985 undertook a single‐blind controlled trial of glucagon in one woman with McArdle disease. The diagnosis was based upon forearm ischaemic exercise testing and muscle biopsy which demonstrated absent phosphorylase activity. Isometric grip strength was measured in the left hand using a rolled sphygmomanometer cuff inflated to 200 mmHg. The grip strength at maximum effort was recorded at 10 second intervals. The participant was asked to report when the forearm became fatigued or painful, at which point exercise was stopped. Various treatments were assessed and neither the participant nor the investigator was aware of the treatment received. Measurements were performed no more than twice a day with at least six hours between the tests. Three baseline measurements were performed, after subcutaneous injection of saline (placebo), two measurements after 2 mg of subcutaneous glucagon and five measurements after administration of 2 mg depot glucagon. The endurance curves for different treatment modalities were plotted. There was a trend towards improvement with glucagon but this was not statistically significant when compared with placebo.

Verapamil versus placebo

Lane 1986 undertook a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over study of the effect of verapamil on muscle pain. The investigators compared three participants with McArdle disease (diagnosed by muscle biopsy) with eight participants with an exertional pain syndrome of unknown cause. Participants were randomly assigned to a placebo or treatment group. After six weeks, medication was stopped for two weeks and then the two groups crossed over following the same regimen for another six weeks. The participants were asked to keep a pain and activity diary. At the same time each week the participants undertook specific timed exercise that would normally produce pain and the maximum level of pain graded on a scale of 0 to 10 during or following this task was recorded. None of the McArdle participants kept satisfactory diaries. Two more participants withdrew from the study because of severe headaches and so were not included in the analysis. No significant benefit was observed in any of the McArdle cases.

Vitamin B6 versus placebo

Beynon 1998 (unpublished data) undertook a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over trial of vitamin B6. Ten participants (eight male and two female, the age of the participants are not recorded) with biochemically and genetically proven McArdle disease received either placebo or vitamin B6 in a once daily dose of 50 mg. Ethical approval was obtained and participant data were compared with age‐ and sex‐matched controls. The hospital pharmacy department made up sachets containing either treatment or placebo and posted them to the participants, who were randomly assigned to one of two groups. There was a six‐week washout phase between the 10‐week treatment or placebo phases. Erythrocyte aminotransferase (eAST) activity was measured to assess vitamin B6 status and participants underwent programmed stimulation electromyogram (PSEM) to assess force generation and fatigability under ischaemic conditions. The investigators were unaware of the phase in the trial for each participant (that is whether placebo or treatment). No significant difference was found between the treatment and placebo.

Oral branched‐chain amino acids versus control

Kushner 1990 studied three patients and three controls comparing the immediate and long‐term effects of oral branched‐chain amino acids. The authors did not specify their diagnostic criteria and the age and sex of the participants were not revealed but the controls were matched for age, sex, height and weight. Prior to the two‐month period of dietary supplementation, the participants underwent assessment daily for three days either in the fasting state or immediately after administration of 100 g dextrose or 0.3 g/kg branched‐chain amino acids, respectively. Participants were then assessed prior to, and after one and two months of branched‐chain amino acid dietary supplementation. Two types of muscle function were measured: maximal concentric strength and muscle endurance (absolute work performed to fatigue). Urine 3‐methylhistidine/creatine ratio was measured. The study failed to demonstrate any immediate or long‐term benefit from oral branched‐chain amino acid supplementation.

MacLean 1998 performed a single‐blind, controlled trial of branched‐chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine and valine) compared with a control non‐calorific drink. The six participants (three males and three females) were unaware of treatment or placebo, but the investigators were not blinded to treatment. The participants exercised for 20 minutes on a cycle ergometer at maximal intensity without experiencing pain or exhaustion. Work intensity converted to Watts and heart rate were measured. Levels of branched chain amino acids were measured in the bloodstream to assess for compliance. Despite increased availability of branched chain amino acids in the bloodstream, exercise capacity was lower in five of the six participants. The authors concluded that functional activity was worse with high‐dose branched‐chain amino acids compared with fasting conditions.

Dantrolene sodium versus placebo

Poels 1990 studied the effect of dantrolene sodium on the second wind phenomenon. Five participants (two women and three men aged 21 to 41 years), in whom muscle phosphorylase protein was shown to be absent on sodium dodecyl sulphate‐gel electrophoresis, were included in a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over trial. Dantrolene was built up over three days to 150 mg, given in three divided doses of 50 mg. Participants received treatment for six weeks with a four‐week washout period, followed by cross‐over to either placebo or treatment. Dose‐dependent side‐effects were noted which included tiredness, somnolence, dizziness and muscle weakness that resulted in dose reduction in four of the five participants. At the end of both treatment phases participants were tested on a bicycle ergometer at 30% VO2 max during two hours and after a 12 hour fast. Surface electromyography (EMG) was recorded during exercise. Participants were asked to use the Borg scale to rate their maximum perceived effort. Statistical analysis showed no significant symptomatic benefit with dantrolene.

Creatine versus placebo

Vorgerd 2000 undertook a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over study of creatine supplementation in nine participants (six men and three women) with enzymatically and genetically proven McArdle disease. Placebo was compared with creatine, initially at 150 mg/kg/day for five days followed by 60 mg/kg/day taken in three divided doses with meals. Each phase lasted five weeks followed by a four‐week washout period and then cross over. Participants were asked to keep a symptom record of exercise intolerance using a fatigue severity scale devised by the authors. On the final day of treatment, clinical measures and laboratory tests were performed including 31‐phosphorous magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P‐MRS), two sets of three minute static plantar flexion exercise under natural perfusion and ischaemic conditions (arterial occlusion). A substantial rise in plasma creatine was noted and the treatment was well tolerated. Five of the nine participants noted some subjective improvement on the basis of a symptom diary when taking creatine compared with placebo. An increased tolerance of workload and depletion of phosphocreatine, which increased significantly during ischaemic exercise, was seen with 31P‐MRS, although an overall increase in muscle phosphocreatine was not seen. A subsequent study undertaken by the same group compared 60 mg/kg creatine with 150 mg/kg creatine given daily (Vorgerd 2002). Nineteen participants were studied in a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. The outcome measures were the same as those used for the lower dose creatine trial. Treatment with high‐dose creatine significantly worsened the clinical symptoms of exercise‐induced myalgia. The authors suggested that one possible explanation for this is that an insufficient adaptation to improved electromechanical efficacy leads to overuse of the muscle contractility in exercise and thus a worsening of symptoms. However, no changes were seen on phosphorous 31P‐MRS.

Oral sucrose versus placebo

Vissing 2003 undertook a single‐blind, randomised cross‐over study of oral sucrose (75 g in a drink) compared with placebo (a drink with artificial sweetener) taken 30 to 40 minutes before fixed intensity exercise on a cycle ergometer for 15 minutes. Twelve participants (seven men and five women) aged 22 to 57 years, known to have McArdle disease (confirmed by muscle biopsy) were assessed on three consecutive days. One participant was taking an oral hypoglycaemic agent for type 2 diabetes. Participants were studied following an overnight fast. The first day was used to define work protocols on a cycle ergometer for 15 minutes; ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) were recorded at one minute intervals, and heart rate and workload were assessed. Blood samples were taken to measure glucose, lactate, pyruvate, ammonia, insulin, and free fatty acids. For the study, 30 to 40 minutes before exercise, the participants received in random order 660 mL caffeine‐free drink containing either artificial sweetener or sucrose 75 g. The method of randomisation was not given and it is not clear whether the two drinks had identical taste. Only pooled participant data were given for all parameters. The mean plasma glucose rose significantly by 36 mg/dL compared with placebo and there was marked hyperinsulinaemia. The mean maximum heart rate was 156 (+/‐ 5) beats per minute following placebo but after sucrose the mean heart rate in the seventh minute of exercise was 34 (+/‐ 3) beats per minute lower than placebo. The rating of perceived exertion dropped when sucrose was ingested compared with placebo (P < 0.001), although the actual data were not given. The trial authors concluded that 'oral ingestion of sucrose can markedly improve exercise tolerance in McArdle disease'. However, when used regularly, sucrose ingestion may potentially result in weight gain. Furthermore it would be of no benefit for unprepared exercise where people could not take such pre‐treatment. Oral sucrose would be contraindicated in people with diabetes.

Andersen 2008b undertook a study to look at the effect of oral sucrose given immediately before exercise. The investigators recruited six participants (five men and one woman) with McArdle disease confirmed biochemically and with DNA studies. The participants were assessed on five separate mornings following an overnight fast. A baseline incremental exercise test using a bicycle ergometer was performed on day one to identify the participants' maximal oxidative capacity to establish the constant workload level to be used for the treatment studies. Participants were given either a caffeine free drink (660 mL) containing 75 g of sucrose or artificially sweetened placebo 40 minutes before exercise, or a caffeine‐free drink (330 mL) that contained sucrose or artificially sweetened placebo five minutes before exercise. Participants, but not assessors, were blinded. The various drinks were given in a random order, but the authors did not specify how they performed randomisation. The participants cycled for 15 minutes at a constant workload of approximately 65% of their maximal oxidative capacity. Perceived exertion was assessed with the Borg rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale. Heart rate was monitored continuously and blood drawn periodically for glucose, insulin and lactate levels (the exact timing is not stated). Individual results were pooled; there was no difference for any variable between baseline cycling following placebo and all participants demonstrated a second wind in the seventh minute of exercise. When 660 mL sucrose drink was given 40 minutes before exercise, improvements compared with placebo were reported with a decrease in RPE of 5.2 (P = 0.009) and a decrease in heart rate of 32 beats per minute (P = 0.02) (exact results were not published). Plasma glucose levels decreased during exercise while lactate levels were higher than placebo but then decreased. When participants received 330 mL of sucrose drink or placebo five minutes before exercise, improvements in the treatment group included an average drop in heart rate of 39 beats per minute (P = 0.00004) and Borg RPE of 7.7 (P = 0.0008). Blood glucose levels increased and were higher in the second half of the exercise test. Insulin levels increased for both sucrose arms and were 300% higher than the 40 minute assessment.

Ramipril versus placebo

Martinuzzi 2008 studied ten participants (seven men and three women mean age 33 years +/‐ 10 years) and 12 control participants (8 men and 4 women mean age 33 +/‐ 7 years) who were given 2.5 mg ramipril for 12 weeks in a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled cross‐over trial with a one‐month washout. The primary outcome measure was an objective assessment of performance using cycle ergometry. The secondary outcome measures were 31P‐MRS of the calf muscle during plantar flexion and subjective outcome measures including the World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Scale (WHO‐DAS 11) and SF‐36 (Short Form 36 Health Survey, a quality of life measure). SF‐36 showed improvement in selected areas in both the treatment and placebo arms. No significant difference was found between the placebo and ramipril in objective exercise parameters, although the WHO‐DAS 11 score improved in ramipril‐treated participants. The treatment was more effective in participants with the D/D ACE genotype, in whom it was associated with a slight but significant increase in peak VO2, although there was no improvement in any other exercise performance parameter.

Carbohydrate‐rich versus protein‐rich diet

Andersen 2008a (previously reported as an unpublished study by Vissing 2007) compared carbohydrate‐rich and protein‐rich diets in a randomised cross‐over study design with one‐week washout. Participants (six male and one female) were assigned to either the carbohydrate or the protein diet according to the sequential order of participant recruitment. One participant was also known to have type 2 diabetes. Each participant was asked to follow a fixed diet with pre‐set recipes for three days. Following a one‐week washout, participants switched to the other diet. The participants were not observed while following the diet and were expected to prepare their own meals, although they were given detailed instructions and asked to weigh and measure food ingredients and complete a form. The diet consisted of either 20% fat, 15% protein and 65% carbohydrate, or 55% protein, 30% carbohydrate and 15% fat. Outcome measures included response to cycle ergometry at constant workload at two‐thirds of maximal exertion for 15 minutes followed by incremental workload until exhaustion. Maximum workload, heart rate and rating of perceived exertion were assessed together with blood biochemical measures of glucose, lactate and insulin. With the carbohydrate‐rich diet there was a significant drop in heart rate and work effort P < 0.0005, although individual data were not given. The mean maximal oxygen uptake was 25% higher on the carbohydrate‐rich diet, 20.2 (+/‐ 1.2), compared with 16.1 (+/‐1.2) mL min‐1kg‐1) on the protein‐rich diet (P < 0.0005).

Results summary

Although there have been a number of treatment trials for McArdle disease, they have included only small numbers of participants (a maximum of 19 participants, in only one study (Vorgerd 2000)). Meta‐analysis was not appropriate because there are virtually no replicated studies, irrespective of methodological quality and those studies that were replicated reported only pooled data from a small number of participants expressed as a difference from baseline, which could not be analysed. There is a lack of evidence to show benefit from supplementation with branched chain amino acids, depot glucagon, dantrolene sodium, verapamil, vitamin B6, high‐dose oral ribose or high‐dose creatine. Low‐dose creatine conferred a modest benefit on ischaemic exercise testing in five out of nine participants, although high‐dose creatine worsened symptoms. Oral ingestion of sucrose taken before exercise significantly improved exercise tolerance and had a greater benefit when given immediately before exercise. A diet rich in carbohydrate may be better than a protein‐rich diet, but this evidence is based upon only small numbers of patients. Ramipril 2.5 mg orally daily showed some subjective improvement in participants with the D/D ACE polymorphism, which is thought to have a modulating effect on the condition, although there was no objective improvement in objective measures of exercise performance.

Discussion

McArdle disease is a rare metabolic muscle disease and the paucity of participants is the reason for the methodological difficulties seen in many of the studies. The largest RCT reviewed included 19 participants and the remaining studies included no more than 12 participants. Eighteen further studies which were excluded from the review merit further description.

Non‐randomised studies

High protein diet

Treatment with a high protein diet has been recommended in the past for people with McArdle disease, but there are no published RCTs to support its use. Two studies have looked at the effect of a high protein diet. Slonim 1985 studied a single affected male aged 50 years. The person suffered cramps on exertion and had significant upper limb muscle wasting and weakness and was confirmed to have McArdle disease following a muscle biopsy, which showed absent muscle phosphorylase on muscle histochemistry. The patient was initially studied during cycle ergometer exercise, serum lactate and alanine levels taken serially were compared with an age and sex matched control. The individual (but not control) was then studied on four separate occasions following a 10 hour fast after which either glucose or protein (broiled beef) were given orally, or saline or fructose were administered intravenously. The person was exercised carefully through a second wind phase and then exercised to exhaustion. The person exercised for a longer period of time following protein ingestion compared with the other nutritional interventions. A high protein diet and daily exercise (which included tennis) were recommended for three years. The participant was then re‐tested following protein or glucose administration and after a mixed meal of his choice, comparison with a control for strength measurement was made after a mixed diet only. The authors reported anecdotal improvements in the person's exercise ability and an improvement in strength in the upper limbs. There was no concealment of allocation and the person's performance may have improved through practice. Furthermore, it is possible that the improvement in strength and endurance noted over the three year period was a consequence of the exercise programme which included one hour of aerobic exercise daily.

Jensen 1990 studied the effect of a high protein diet for six weeks on a male participant with McArdle disease, confirmed by muscle biopsy. Bicycle ergometry was performed two hours after meals of the individual's normal diet (15% protein, 42% fat and 43% carbohydrate) and after six weeks on an isocaloric high‐protein diet (28% protein, 29% fat and 43% carbohydrate). Maximal muscle strength was measured by a stepwise increase in workload by 10 W: two minutes work followed by 10 minutes rest. Endurance at submaximal muscle strength was measured after 15 minutes rest. Treadmill exercise combined with 31P‐MRS was then studied two hours after a meal on the usual diet, following an intravenous glucose (20% solution) infusion, after an intravenous infusion of amino acids (0.3g/kg body weight/hr) and after six weeks of high protein diet. Six age matched normal controls were also examined with phosphorous‐31 nuclear magnetic resonance (31‐PNMR) to study adenosine triphosphate (ATP), phosphocreatine (Pcr) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). The controls did not receive any infusion. On his usual diet, the working capacity of the participant measured at treadmill exercise was approximately one half of that of the controls. ATP/(Pcr+Pi) and Pi/Pcr ratios were within the normal range at rest. During exercise there was a rapid decrease of Pcr and an equivalent rise in Pi, whereas ATP was unchanged at all levels of work load. During the intravenous glucose infusion, the expenditure of Pcr at each level of work load during hyperglycaemia was significantly less than during normoglycaemia. Following an increase of the daily protein intake from 15% to 28% on an isocaloric diet of unchanged carbohydrate content, the endurance at submaximal work load during bicycle ergometry was increased from five to eight minutes and the maximal capacity at graded bicycle exercise improved by 25%. Treadmill exercise performance improved by 40%. The 31P‐spectrum showed decreased expenditure of Pcr at the maximum work intensities and the Pi/Pcr ratios improved from 3.1 at the usual diet to 1.5 at high protein diet. In comparison, the Pi/Pcr ratios were 1.4 during glucose infusion and 4.4 during infusion of amino acids. Intravenous amino acid infusion at a rate of 0.3g/kg body weight/h was not associated with any improvement of the phosphorous energy metabolism nor of the working capacity during treadmill exercise. The findings were an increase in performance and high energy kinetics following a high protein diet and glucose infusion, but not following administration of intravenous amino acids. There was, however, no concealment of allocation and statistical analysis was not appropriate because the study included only one participant.

High fat diet

Pearson 1961 first described the second wind phenomenon and related this to delayed mobilisation and utilisation by the muscles of free fatty acids as a secondary energy source during muscle exercise. A beneficial action was demonstrated of a continuous infusion of emulsified fat in 4% glucose on the muscle performance of a participant. On the basis of this case report, Viskoper 1975 assessed the potential benefit of a high fat diet for three days in a single case study. The participant, an affected 21 year old male, was exercised on a bicycle ergometer at a workload of 60 kW for two and a half minutes. Later he was asked to maintain sustained abduction of the deltoid muscle to 90 degrees. Blood pressure was taken at one, two and five minutes, a blood sample was taken to measure free fatty acids, triglycerides and lactic acid, and EMG monitoring was conducted during eccentric exercise. The participant reported subjective feelings of increased fitness, but this could not be confirmed objectively by the researchers. In a second branch of the study isoprotenol was administered as a means of raising plasma free fatty acid levels, a dose of 10 mg three times a day was given for two weeks while the participant was on a normal diet. No beneficial effect was observed. Busch 2005 and Vorgerd 2007 described the effects of a ketogenic diet in one 55 year old male with McArdle disease by increasing the fat content of his diet by 80% with 14% protein for one year. His exercise tolerance was reported to be increased three‐ to 10‐fold. Maximum strength and activity also improved and CK levels reduced. Ketogenic diet did not alter 31P‐MRS data during rest, work and recovery. Another observational study of ketogenic diet was set up to evaluate long‐term effects of a ketogenic diet in one woman and three men with McArdle disease aged 41, 45, 48 and 52 years respectively (mean age 46 years), by increasing dietary fat content to 70% with 20% protein for 18 months. Serum ketone bodies, creatine kinase levels, maximum strength and 6 minute walking test were measured every eight weeks. After two months one man stopped the diet; the remaining participants continued for 18 months. Creatine kinase levels fell by 40% but strength testing and the six minute walk test were not significantly improved. None of the participants chose to continue with the diet (unpublished data, Schoser 2008).

An unblinded observational study to evaluate the importance of lipids as an energy source during exercise was undertaken by Andersen 2009. Ten participants with McArdle disease (eight male and two female) were required to cycle at a constant workload of 70% of their maximum oxygen consumption. On separate occasions in a random order they were given infusions of either normal saline, glucose, nicotinic acid (to block lipolysis) or 20% Intralipid (an intravenous lipid emulsion). Participants were required to cycle at a constant workload of 70% of their maximum oxygen consumption. Exercise capacity was determined by monitoring the heart rate response to exercise, which showed a significant increase with the intravenous lipid emulsion and nicotinic acid compared with normal saline and glucose. The authors concluded that although lipids are an important source of fuel during exercise, in people with McArdle disease there does not appear to be increased lipid metabolism during exercise.

In another study of 11 participants with McArdle disease compared with 11 healthy controls, fatty acid oxidation during exercise was assessed using an intravenous solution of the radiotracer U‐13Cl palmitate, and showed similar carbohydrate and fatty acid oxidation in both groups. However, during exercise performed on a cycle ergometer there was an increase in fatty acid oxidation in the participants with McArdle disease compared with the control group during the second wind. However, following the second wind despite increased plasma levels of free fatty acids there was no further increase in fatty acid oxidation. The authors concluded that the key role of glucose is to facilitate fat oxidation and thus the block in glycogenolysis in McArdle disease may limit the capacity for fat oxidation (Orngreen 2009). Thus, when considering treatment aimed at enhancing fat use in McArdle disease, consideration should be given to adding interventions aimed at modifying the tricarboxylic acid pathway.

Glucagon administration

There have been three studies to evaluate glucagon. Day 1985 is included in this review and did not report any demonstrable effect with glucagon supplementation. Two earlier studies excluded from the review merit further discussion. Kono et al. gave glucagon to a single female participant aged 26 years (Kono 1984). No placebo was used and there were no control participants. Blood levels for creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, glucose, free fatty acids and ammonia were measured. The participant was exercised for three minutes. The authors suggested that glucagon improved exercise tolerance. The participant was not assessed blindly and had also co‐incidentally been taking coenzyme Q10 for one year which had resulted in a subjective improvement of her symptoms. Subcutaneous glucagon administration improved work tolerance on a bicycle ergometer. Normally the participant was exhausted after three minutes but with glucagon she exercised for 30 minutes with a second wind at three and ten minutes. An ischaemic lactate test undertaken with glucagon led to a rise in plasma lactate. There were no controls, and no concealment of allocation and no statistical parameters were used because this was a single case study. Mineo 1984 studied two female participants with McArdle disease aged 26 and 29 years, and two male cases with Tarui's disease, aged 44 and 20 years. (Tarui's disease is a glycogen storage myopathy caused by a deficiency of the glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase). One participant with McArdle disease and one with Tarui's were exercised on a bicycle ergometer with and without glucagon pre‐treatment following an overnight fast. All four participants underwent a modified ischaemic exercise test and were given the following: oral glucose, glucagon and glucose combined with insulin. The authors found that the participant with McArdle disease achieved a second wind more efficiently with glucagon administration during cycle ergometer exercise. No benefit was seen in the case with Tarui's disease. This study lacked concealment and statistical analysis. Further studies would be necessary to determine whether regular use of glucagon would benefit patients. However, any consideration of the use of glucagon as a form of possible therapy for McArdle disease should also be considered in the context of its long‐term side‐effects, which include haemolytic anaemia.

Other interventions

Non‐randomised studies for other interventions have included vitamin B6, oral ribose, intravenous glucose, creatine and gentamicin.

Phoenix 1998 reported the effect of withdrawal of daily 50 mg vitamin B6 in a male participant with McArdle disease. The participant had been taking vitamin B6 as a supplement for two years. The effect of withdrawal of treatment was assessed. The participant was blind to receiving either vitamin B6 or placebo, which was allocated by the hospital pharmacy after a period of observation. The outcome was assessed using vitamin B6 status as assessed by eAST activity. Objective muscle function was evaluated by stimulation of the adductor pollicis muscle via the ulnar nerve at the wrist using PSEM providing information on force and compound muscle action potential (CMAP) together with qualitative data on symptoms. Qualitative changes in feelings of reduced well being were noted off treatment and there was a rapid decline in vitamin B6 status. The PSEM studies showed a reduction in the participant's ability to recover during the post ischaemic recovery phase during withdrawal of vitamin B6 although there was no clear effect of vitamin B6 on the CMAP. Vitamin B6 withdrawal did not affect the serum creatine kinase levels or frequency of myoglobinuria. Wagner 1991 assessed the effect of high‐dose oral ribose given to a 20 year old patient and six normal controls, which were not matched for age or sex. While the participant was pedaling a cycle ergometer, 3 g oral ribose was given every 10 minutes. The study reported an increase in exercise capacity from 60 W to 100 W. Blood lactate levels were tested before and after exercise. The participant reported fewer cramps, although there were no quantitative or qualitative assessments to substantiate this.

Lewis 1985 showed that intravenous glucose is associated with a partial normalisation of an excessive cardiac output in response to exercise together with improved exercise tolerance. They studied a single male with McArdle disease and two normal controls (one male and one female). The 31P‐nuclear magnetic resonance (31P‐NMR) of the forearm flexor muscles was assessed during exercise using a handgrip dynamometer (modified to work in the magnetic field) to record maximal handgrip. Repetitive exercise was performed two hours post prandially on a normal mixed diet and during an intravenous infusion of 60 mL of a 50% glucose infusion. Under control conditions the person with McArdle disease fatigued with an impending muscle contracture at two minutes and 10 seconds. From rest to fatigue the participant's forearm muscle PCr declined precipitously and Pi increased markedly but ATP was only slightly reduced. Plasma glucose levels rose three times during the glucose infusion. The participant performed maximal handgrip exercise for more than seven minutes. During glucose infusion PCr fell and Pi increased to a much lesser extent than under control conditions. In the healthy controls forearm PCr tended to decline similarly and Pi tended to increase less in the healthy participants than the person with McArdle disease. Exercise in the control participants was no different with the glucose infusion. Haller 2002 studied the effect of intravenous glucose on the second wind. They studied nine participants (eight with complete phosphorylase deficiency and one with 3% of normal phosphorylase activity). Participants exercised on a cycle ergometer for about 40 minutes. Initial work capacity was determined in the first six to eight minutes, then workload was reduced for five to 10 minutes. The workload was again progressively increased to determine peak performance at 25 minutes. Immediately afterwards 50 mL of 50% glucose was infused over one to two minutes followed by a continuous infusion of 10% dextrose at a rate of 6 mL/min for the duration of exercise. Exercise was continued for 40 minutes. Participants were assessed three times over a 24‐month period and the mean results presented. Heart rate was continuously monitored, gas exchange and cardiac output were measured at rest and during peak exercise within six to eight minutes. The glucose infusion resulted in a 20% increase in oxidative capacity.

O'Reilly 2003 studied a single case on and off creatine at a dose of 25 g/day for five days. The author was also the participant in the trial and thus, there was no concealment, he was exercised to exhaustion in the second wind phase of exercise, achieving a work rate of 275 to 325 W. No benefit was noted with creatine supplementation.

Schroers 2006 tested the short‐term efficacy of gentamicin in four participants with McArdle disease who had stop mutations. These were given daily intravenous gentamicin sulphate 8 mg/kg/day each day for 10 consecutive days in an open study. Plasma creatine kinase levels decreased but not significantly. Participants were evaluated with 31P‐MRS but no difference was detected. Further studies on myoblasts demonstrated no increase in phosphorylase expression. Thus, short‐term gentamicin treatment appeared to have no effect on performance in McArdle disease. It might be that the treatment was not given for long enough or the type of non‐sense mutation was not amenable to the effects of the drug. The development of new compounds which induce read‐through of stop codons, such as PTC 124 (Ataluren), and drugs that might up‐regulate the brain phosphorylase isoform, such as valproic acid, could be promising. Initial studies on cell culture and animal models are required before large scale clinical trials can be contemplated.

Outcome measures

A recurrent theme of therapeutic studies for McArdle disease is the restricted availability of patients. Future studies will need to be multicentre and probably multinational. The limited evidence suggesting that females with McArdle disease may differ in phenotypic expression to males opens the question of considering a gender effect when planning future treatment trials. However, before such studies can be contemplated several key issues must be resolved. First is the need to specify rigorously defined methods for assessment of muscle performance and fatigue in McArdle disease. Whilst objective physiological tests are valuable in determining proof of principle, there is also a need for assessments that relate more to lifestyle and day‐to‐day demands on skeletal muscle, for example assessments of walking rather than cycling. The features of McArdle disease are fatigue, pain, speed of recovery and the onset of the second wind phenomenon. Future studies will need to be clear about which aspects of McArdle disease they wish to improve. There is at the moment too much emphasis on impairment (biochemical and physiological measurements) and not enough on disability (activities) and handicap (participation). Other challenges that have emerged from this review relate to the chemical composition of dietary supplements. For example a high protein diet does not seem to elicit the same effect as intravenous or oral amino acids. Once such issues have been adequately addressed, the path is clear for new studies to clarify the value of many of the treatments that have been addressed thus far in a limited fashion and to define modalities for new interventions.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. Red (‐) = high risk of bias; yellow (?) = unclear risk of bias, green (+) = low risk of bias.