Универсальная (на базе школ) профилактика незаконного употребления наркотиков

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to studies awaiting assessment

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

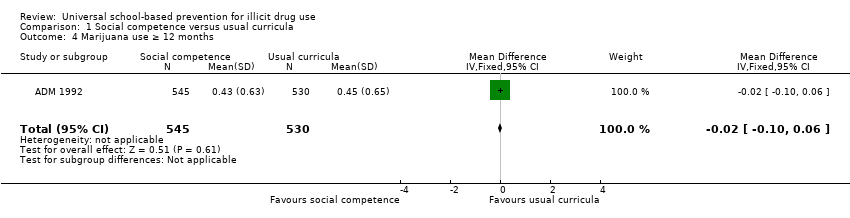

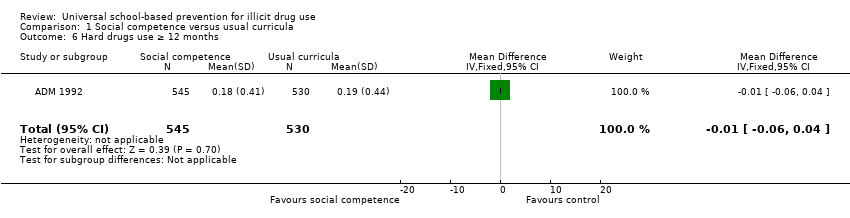

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 1360 6th‐grade students enrolled from 2 southern New England towns, USA. Academic years 1980 to 1981, 1981 to 1982 | |

| Interventions | Experimental: ADM (Adolescent Decision‐Making) is a cognitive‐behavioural skills intervention to familiarise students with the basic concepts of effective decision‐making, to promote role flexibility, to increase students' abilities to recognise and manage peer pressure, and to enhance students' ability to turn to others for information and support when faced with decisions Social competence approach Deliverer: not reported n = 680 Modality: not reported N of sessions: 12 sessions during 6th grade Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 3 months Control: type of intervention not reported, n = 680 | |

| Outcomes | Improvement of decision‐making processes Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, hard drugs use | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test (at the end of the intervention) and at 24 months (at 8th grade) after the end of the intervention. Analysis sample at 24 months follow‐up = 1075 (79% of the original sample), intervention group n = 545, control group n = 530 Attrition: 8.9% at post‐test Data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "at a first step in randomisation, schools were grouped into homogeneous clusters based on socioeconomic status and ethnic composition; classrooms were then randomly divided into Program and Control group" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | There were no significant differences in attrition rate between groups; logistic regression revealed an interaction for alcohol at baseline (control drop‐outs were more likely to use alcohol at baseline than control 'stayers'); no interaction was found for tobacco, marijuana or hard drugs |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Questionnaires had code number but no name of the students. Trained raters scored coded questionnaires without knowledge of group assignment |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 6527 7th to 8th grade students enrolled from 30 junior high schools in California and Oregon (USA), 1984 to 1990 school years. 3912 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: project ALERT, targeting alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana use, seeking to motivate the students to resist pro‐drug influences and to give them the skills to do so Social influence approach. n = not reported (20 schools): Group 1: adult health educator alone led n = not reported Group 2: adult health educator led, teen assisted n = not reported Deliverer: Group 1 taught by an adult health educator alone Interactive modality N of sessions: 8 lessons in 7th grade and 3 in the booster session the following year Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: overall over 2 school years, n of months not reported Control: usual curricula, n: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Use of alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana, measured by a questionnaire administered before and after delivery of 7th grade curriculum (baseline and 3 months later), before and after 8th grade booster lessons (12 and 15 months after baseline). Beliefs about consequences of using substances, perceptions about use in peers, resistance self efficacy, expectations of use in next 6 months | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test and at 3 months follow‐up after the end of the intervention Analysis sample n = 3916, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported No data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "blocked randomisation by district, assignment restriction to a subset that produced little unbalance among experimental conditions in school test score, language spoken at home and drug use"; unit of randomisation: schools |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "we found no evidence that either attrition rates or which students were lost from the analysis varied across experimental conditions" |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Regression methods were used at the analysis stage to adjust for chance differences among the groups |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 5412 7th grade students enrolled from 55 middle schools in South Dakota (USA), 1997 to 1999 school years | |

| Interventions | Experimental: project ALERT (revised), targeting alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana use, seeking to change student's beliefs about drug norms and consequences, and to help them to identify and resist pro‐drug pressures Social influence approach n = 2810 Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N of sessions: 11 lessons in 7th grade and 3 in 8th grade Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 18 months | |

| Outcomes | Use of marijuana, measured by a questionnaire administered before the delivery of 7th grade curriculum and after the administration of 8th grade lessons (approximately 18 months later). Drug use was assessed for lifetime use, past month and weekly use | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed: at post‐test Attrition at post‐test (18th month): 8.8% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified randomisation by geographic area and community size and type (city, town and rural area). Within each strata blocked randomisation with blocks of 3 was used. Unit of allocation: school. A restricted assignment was used to reduce imbalance among groups using an index of school academic performance and socioeconomic status and the existence of a drug prevention programme in the district |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | A restricted assignment was used to reduce imbalance among groups using an index of school academic performance and socioeconomic status and the existence of a drug prevention programme in the district |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Students who dropped out were more likely to be non‐white, of lower socioeconomic class and to have tried alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana. However, the attrition rate and characteristic of students dropped out were similar across groups |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Students in the control group were less likely to be white and more likely to use marijuana. To reduce the effects of these differences there was adjustment for baseline covariates (use of drug, demographic characteristics, intentions and belief about drug use, perceived norms, pressure and social approval) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 1649 7th grade students from 8 Pennsylvania middle schools (USA) | |

| Interventions | Experimental: project ALERT (revised), targeting alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana use, seeking to change student's beliefs about drug norms and consequences, and to help them to identify and resist pro‐drug pressures Social influence approach Group 1: adult led, n = not reported Group 2: adult led, teen assisted, n = not reported Deliverer: project staff Interactive modality N of sessions: 11 lessons in 7th grade and 3 in 8th grade Booster: no Duration of the intervention: overall over 2 school years, n of months not reported Control group: types of intervention: not reported, n: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Marijuana use (last month, last year, lifetime) on a 5‐point scale | |

| Notes | Attrition (overall): 27.5% Outcome assessed at post‐test and 12 months after the end of the intervention No data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "each of the eight schools randomly assigned two 7th grade classrooms to each of three conditions: adult led project ALERT, teen assisted Project ALERT, control" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "attrition was comparable across the three conditions" |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Quote: "no consistent pattern of differences emerged from the cohort, there was satisfactory evidence od equivalence among the treatment and control condition" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "self report questionnaire was administered by school personnel to treatment and control classrooms" |

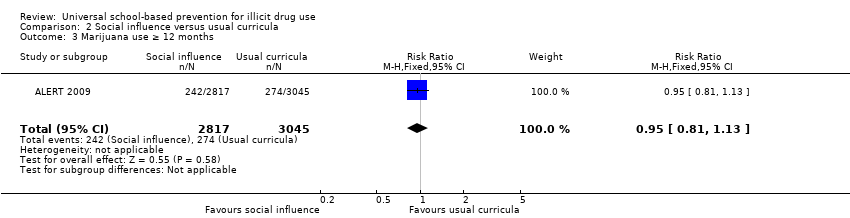

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

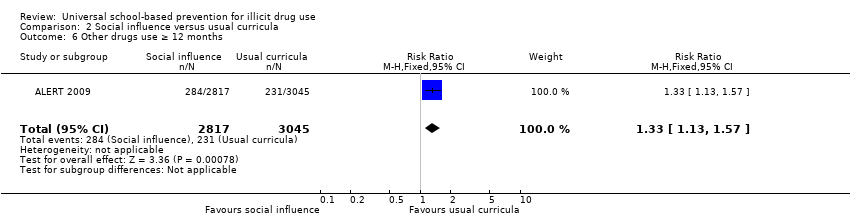

| Participants | 5883 6th grade students from 34 schools in the USA 2004 to 2005 and 2005 to 2006 school years | |

| Interventions | Experimental: ALERT programme. Manualised classroom‐based substance use prevention curriculum which targets cigarette, alcohol, marijuana and inhalant use, motivates students not to use substances, provides skills to resist pressure from peers, supports attitudes and beliefs that mitigate substance use, addresses normative perceptions about peer use and acceptance Social influence approach N = 2817 Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N of sessions: 11 lessons in 6th grade and 3 in the booster session the following year Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: overall over 2 school years, n of months not reported Control: usual curricula, n: 3045 | |

| Outcomes | Marijuana use, inhalants use. Drug use was assessed for lifetime use; last 30 days | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed: at post‐test and 1 year after the end of the intervention Attrition (overall): 21% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "assignment was implemented through the use of computer generated random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Quote: "one of us randomly assigned schools to the experimental condition, blocked by school district. Assignments were made on a flow basis as soon as a district were paired and randomly assigned to a condition" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "differential attrition was not a problem because attrition was near 21% in both groups" |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | High risk | Schools in the control groups were more likely to offer prevention programmes not related to Project ALERT |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 33 7th grade students from a mid‐school in Albuquerque, New Mexico (USA). January 1985 to September 1985 | |

| Interventions | Experimental: ASAP (Alcohol and Substance Abuse Prevention Program) Knowledge‐focused approach Control group: Berkeley Health Education Curriculum: the curriculum presented short‐term and long‐term consequences of alcohol and drug abuse in a traditional work‐book and didactic format, as well as role‐play exercises, small group exercises and out of class assignments; discussing peer pressure and strategies to resist peer pressure. (n = 16) Knowledge‐focused approach Deliverer: project staff Interactive modality N of sessions: not reported Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 6 months | |

| Outcomes | Knowledge: consequences of use | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test and at 8 months follow‐up after the end of the intervention No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "subjects were randomly assigned to either an experimental or control group |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 1416 2nd to 6th grade students enrolled across 4 Catholic schools in Louisiana (USA): 670 participants initially | |

| Interventions | Experimental: ATD programme (Alcohol/Tobacco/Drug use/abuse), targeting alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana use Social influence approach n = 348 Deliverer: teacher Modality not reported N of sessions: not reported Booster: no Duration of the intervention: overall over 2 school years, n of months = 18 Control: HEE programme; active control condition focused on obesity prevention (the Healthy Eating and Exercise), n: 313 | |

| Outcomes | Tobacco and alcohol expectancy Tobacco, alcohol and drug use | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at 6, 12 and 18 months after the initiation of the intervention Attrition not reported Data on substance expectancies for meta‐analysis are partially reported in text and needed recalculation, while data on substance use are presented as beta and only in the footnotes of table 5; absolute numbers are reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The randomization was conducted by biostatisticians at Pennington Biomedical Research Center after the baseline data collection was completed. Therefore, treatment condition assignment was unknown to all parties prior to that point" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Seems to be a per protocol analysis |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | High risk | Statistically significant differences in: % with family member(s) who smoke |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: "Participants and research team members interfacing with the schools could not remain blind to |

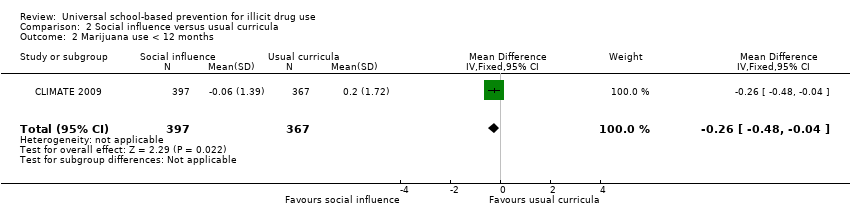

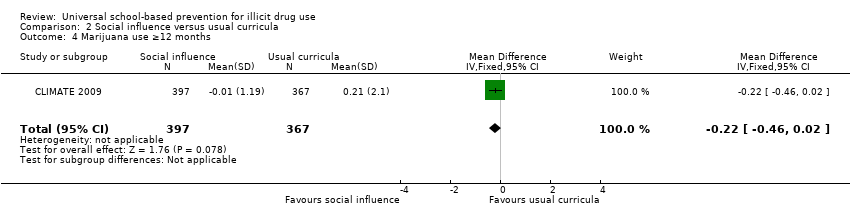

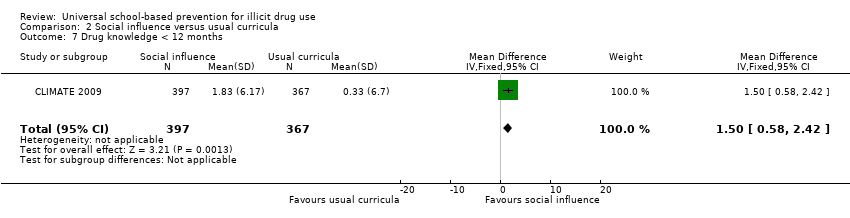

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 764 students; mean age 13 years form 10 high school cross Sidney metropolitan area (Australia) | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Climate Schools Alcohol and Cannabis course: each lesson included 15 to 20 minutes of Internet‐based lesson completed individually where students followed a cartoon storyline of teenagers experiencing real‐life situations and problems with alcohol and cannabis. The second part of each lesson was a predetermined activity delivered by the teacher to reinforce the information taught by the cartoon Social influence approach n = 397 Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N of sessions: 12 Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 6 months Control group: usual health classes: n = 367 participants | |

| Outcomes | Cannabis knowledge questionnaire adapted form the Cannabis Quiz Cannabis use: assessed from a questionnaire in the 2007 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS); assessed the frequency of use | |

| Notes | Attrition (overall): 20% Outcome assessed at post‐test, 6 and 12 months after the end of the intervention No data suitable for meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "the 10 participating schools were assigned randomly using an online randomisation system (www.randomized.org) to either a control condition or the intervention condition" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 48% of the students completed the post‐test survey in the experimental group and 69% in the control group. (3% completed the 18 months follow‐up survey in the experimental group and 75% in the control group. There was no evidence of differential attrition |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | The intervention group had higher alcohol and cannabis‐related knowledge and higher alcohol consumption |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 798 students from 3 senior high schools in Wuhan, a city in central China, participated in the study at baseline; school years not reported | |

| Interventions | Experimental: project CMER was designed to address the major cognitive, attitude, motivation and coping skills as the keys to prevent illicit drug use, such as general drug information, the negative impact of drug use, the relationship between the behaviour of drug use and AIDS, peer resistance skills, emotion adjusting skills Social competence approach n = 798 Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N of sessions: 6 lessons Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 3 months Control: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Attitude to drug use, knowledge of drugs, type of drug, social impact of drug use, drug use consequences for health Addiction, motivation to use drug, peer resistance skills Illegal substance use at least once, drug use in the previous 30 days, drug use more times | |

| Notes | No attrition Outcome assessed at 3 months after the intervention Data are suitable for meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A missing data analysis was performed to ensure completeness of the questionnaires. Incomplete cases were excluded and descriptive analyses were performed." |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Quote: "A series of t‐tests examined whether the 2 groups differed in any of the variables, and the results showed that there were no significant differences (all P>0.05) in any of the substance use variables except for the mean scores of drug use consequences to health. This indicated a high degree of comparability between groups prior to the intervention." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 114 8th and 9th grade students volunteering for 2 service opportunity courses (Cross‐Age‐Tutoring and School Store). Initial sample included 58 students in Cross‐Age‐Tutoring and 56 students in School Store. Spring 1979 to Spring 1980. California, USA | |

| Interventions | Experimental 1. Cross‐Age‐Tutoring: students were taught tutoring and communication skills and spent 4 days a week tutoring elementary students (n = 29) 2. School Store: students were taught business and interpersonal skills and operated an on‐campus store (N = 28 experimental) Deliverer: project staff Interactive modality N of sessions: not reported Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 6 months Control: no intervention (n = 29 in Cross‐Age study; n = 28 in School Store study | |

| Outcomes | Any drug current use, drug knowledge | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test and at 1 year after the end of the intervention No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "voluntary students were randomly assigned to experimental or control condition" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Attrition similar in all conditions |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 2071 6th grade students in the Lexington‐Fayette County public schools, Kentucky (USA), 1987 to 1988 school year | |

| Interventions | Experimental: DARE programme. Cognitive, affective and social skills strategies, aimed to increase students' awareness of adverse consequences of drug use, build self esteem, improve decision‐making and assertiveness in social settings (n = 1550) Deliverer: police officers Interactive modality N of sessions: not reported in 6th grade Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 4 months | |

| Outcomes | Frequency of past year use of marijuana. | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test, 1, 2 , 5 and 10 years after the end of the intervention No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis. Authors contacted without reply | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 22.1% for the experimental group and 20.7% for the control group at 2 years follow‐up (8th grade) |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Chi² analysis revealed that there were no significant differences in attrition by condition at any follow‐up period |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not provided |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 1402 5th and 6th grade students from 20 North Carolina elementary schools (USA) | |

| Interventions | Experimental: DARE programme was a cognitive, affective and social skills strategies, aimed to increase students' awareness of adverse consequences of drug use, build self esteem, improve decision‐making and assertiveness in social settings Social competence approach n = 685: Deliverer: law officer Modality not reported N of sessions: 17 weekly lessons Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 4 months (August 1988 to December 1988) Control: usual curricula, n= 585 | |

| Outcomes | Self reported use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana and inhalants, intentions use of these substances, several selected attitudinal variables Lifetime use, current use | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test (not reported) Analysis sample n = 1270, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported Data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "schools were randomly assigned to receive DARE project or to be placed in the control condition" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "students were equally likely not be present in the DARE and control schools. There were no consistent patterns indicating that students who did not completed the study were at greater risk for drug abuse" |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Groups not similar at baseline for some characteristics but adjustment for imbalance was done during the analysis using appropriate methods |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Questionnaires were compiled by participants using an anonym code and in a manner that ensured privacy without access by teachers, parents or project staff |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 6728 7th and 8th grade students from 24 middle and junior schools in Minnesota (USA), 1999 to 2001 school years. 6237 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: 2 conditions: 1. DARE only: provided skills in resisting influences to use drugs and in handling violent situations. Its also focused on character building and citizenship skills Social competence approach n = 2226 Deliverer: law officer + teachers Modality not reported N of sessions: 10 Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 2 school years 2. DARE + DARE Plus: DARE Plus had 2 components: the first was a classroom‐based, peer‐led, parental involvement programme focused on influences and skills related to peers, social groups, media and role models. The second component involved extra school activities Social competence approach n = 2221: Deliverer: law officer + teachers Modality not reported N of sessions: 10 sessions implemented by law officer + 4 sessions implemented by teachers Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 4 weeks Control: "delayed program", n = 1790 (had the opportunity to receive the DARE Plus programmes in 2001 to 2002, after the final follow‐up) | |

| Outcomes | Self reported tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use; multidrug use; violent behaviours among the students, physical victimisation Past use of alcohol, current use of tobacco | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test (not reported) Analysis sample n = 5239, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported No data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The study design involved 24 middle and junior high schools in Minnesota that were matched on socioeconomic measures, drug use and size, and randomly assigned to 1 of 3 conditions |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | 84.0% retention at final follow‐up. Reasons for loss to follow‐up included students relocating (10.8%), absenteeism (1.4%), parental refusal or non‐deliverable consent form (2.3%), student refusal (1.0%), and home schooling, limited English or special education (0.5%). Loss to follow‐up rates did not differ by study condition. The main outcomes of the study were analysed using growth curve analyses. This analytic method permits retention of participants who do not have complete data |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Quote: ''At baseline, there were no significant differences between the 3 conditions." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 465 students from a high school in southwestern USA | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Drug Resistance Strategies project was a communicative resistance skills training through film and live performance. The curriculum utilised actual narrative accounts that were performed by actors and couched in a musical drama format. The film curriculum was produced on film and transferred to videotape; the screenplay was then adapted into a live performance format 4 experimental conditions: Social competence approach n = not reported Deliverer: project staff Modality not reported Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 1 month Control: programme not reported, n = 89 | |

| Outcomes | Students were pre‐tested with a questionnaire containing demographic information, current usage and amount, use of resistance skills, confidence and difficulty of resistance, attitudes, perceived normative support for use of drugs and alcohol, and use of planning to avoid drugs | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test 1 day after; assessed at follow‐up after 1 month Analysis sample n = 5239, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: " 21 classes were randomly assigned to one of four intervention conditions and one control condition" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear attrition rate |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 2678 students aged 13 to 14 years from 12 metropolitan and 4 country district in Australia, 1997 to 1999 school years. 2678 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Gatehouse Project aimed at increase the level of emotional well being and reduce the substance use through: building a sense of security and trust, increasing skills and opportunities for good communication and building a sense of positive regard through valued participation in aspects of school life Social competence approach n = 1335 Deliverer: project staff Modality not reported N of sessions: 20 Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: 3 months Control: n = 1343 | |

| Outcomes | Mental health status: reported anxiety/depressive symptoms Social relation: availability of attachment and conflictual relationship Victimisation School engagement Tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use: current use of tobacco and alcohol, past month use of tobacco and past 2 weeks use of alcohol; regular use of tobacco and alcohol; use of cannabis in the previous 6 months | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at the end of year 8, 9, 10 (12, 24, 36 months after the initiation of the intervention, first surveys at 5 months after the end of intervention) Analysis sample not reported, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported Data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "district were randomly allocated to experimental or control condition. Using simple random sampling 12 school in the metropolitan area and 4 in the country region were selected from the intervention district and 12 and 4 from the control district" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Analysis done with the intention‐to‐treat principle |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | The intervention group reported only slightly lower levels of risk factors such as parental separation and parental smoking |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 678 1st grade students from 9 primary schools in the USA, 1993 school year | |

| Interventions | Experimental: 2 experimental conditions: GBG programme involves a whole class strategy to decrease disruptive behaviour and reduce early‐onset tobacco smoking n = 192 Booster: no ‐ Family‐school partnership intervention improves achievement and reduces early aggression and shy behaviour by enhancing parent‐school communication and providing parents with effective teaching and child behaviour management strategies n = 178 Booster: yes Other approach Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N of sessions: not reported Duration of the intervention: 1 school year Control: standard educational setting, n = 196 | |

| Outcomes | Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, inhalants and other illegal drug use | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at 5, 6 and 7 years (6th through 8th grades) Analysis sample n = 566, 192 intervention group, 178 control group Data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "students were assigned at random to the three designated classrooms with balancing for male‐female ratio" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "attrition across follow up period was unrelated to intervention status and participants lost at follow up did not differ from participants with complete data with respect to baseline teacher rating, academic achievement and demographic characteristics." |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Quote: "we found no statistically significant differences in terms of sociodemographic characteristics across groups" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "audio computer assisted self interview (ACASI) methods were used to administer standardized items; the student marked their responses under private conditions that were maintained by a member of the assessment staff, who took care not observe the responding and to prevent observations by the vicinity" |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 19 schools, 41 classrooms, 407 first grade children within 5 urban areas in Baltimore during 1985 to 1986 | |

| Interventions | Experimental group: 8 GBG classrooms (n = 238) Based on life course/social field theory "The teacher posted basic classroom rules of student behavior, and during a particular game period all teams received a reward if they accumulated four or fewer infractions of acceptable student behavior. The GBG was played during periods of the day when the classroom environment was less structured, such as when the teacher was working with one student or a small group while the rest of the class was instructed to work on assigned tasks independently. Over time, the game was played at different times of the day and during different activities. In this manner, the GBG evolved from a precise procedure that was highly predictable and visible, with a number of immediate rewards, to a procedure with an unpredictable occurrence and location, with deferred rewards." Other approach Deliverer: trained teacher Modality: interactive Duration: 2 years Sessions: 3 per week lasting 10 minutes, increasing to 40 minutes Booster: no Control group: no intervention : 6 classrooms (n = 169) | |

| Outcomes | CIDI‐UM modified (Composite International Diagnostic Interview ‐ University of Michigan: a scale for occurrence of drug abuse and dependece disordes), to reflect the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐IV (DSM‐IV) diagnostic criteria, was used to determine the lifetime, past year and past month occurrence of drug abuse and dependence disorders. Diagnoses were derived in accordance with the DSM‐IV criteria, using a computerised scoring algorithm | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at age 19 to 21 by blinded interviewers Attrition 24.1% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Multilevel randomised design; no further description of sequence generation Quote: "The first stage of the design involved selecting five distinctly different socio‐demographic urban areas in Baltimore. The second stage of the design involved assigning individual children to first grade classrooms within each school so that classrooms were nearly identical before they were assigned to the intervention condition. The third stage of this design was random assignment of classrooms and teachers to intervention condition within each intervention school" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description of method of allocation concealment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 24.1% attrition |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | No differences between the GBG and control sample were found |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | The interviewers were masked to the first grade intervention condition |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 511 students from 4th, 5th and 6th grade from 23 classes of 6 elementary schools in northwest Arkansas (USA), during spring 1989. 501 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Keep A Clear Mind Program (KACM) was based on a social skills training model, aimed to help children to develop specific skills to refuse and avoid "gateway" drug use Social competence approach n = not reported Deliverer: project staff + teacher Modality not reported N of sessions: 4 Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 1 month Control: not reported, n= not reported | |

| Outcomes | Alcohol, tobacco and marijuana use; intentions, beliefs and knowledge | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test: 2 weeks after the implementation of the programme Attrition at post‐test: 11% No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "students were blocked on school and grade level then randomly assigned by class to either an intervention or control group" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "similar proportions of students completed the post test questionnaire in both groups" |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Quote: "no significant differences were found between intervention and control group at pretest on the primary variables with one exception: the control group included a great number of black students" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 6035 7th grade students from 35 middle schools in Arizona, USA. During 1997 to 1998. 4234 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Drug Resistance Strategies Project (DRS) implemented and evaluated in the "Keepin' it REAL curriculum". The curriculum is aimed to develop drug resistance strategies, life skills and decision‐making, communication competences, knowledge. 3 parallel versions: a Mexican American centred version (oriented toward Mexican American culture), a Black and White centred version (oriented toward European American and African American culture) and a multicultural version Social competence approach n = 25 schools Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N of sessions: 10 sessions in 7th grade Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: 18 months Control: already existing substance use prevention programmes, n = 10 schools | |

| Outcomes | Recent substance use (alcohol, tobacco, marijuana). Resistance strategies (alcohol, tobacco, marijuana). Self efficacy. Intent to accept. Positive expectancies. Norms | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at: post‐test after the implementation of the booster (6 months after the initiation of the intervention), 8 months after curriculum implementation and 14 months after curriculum completion Analysis sample n = 4234, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The research team stratified the 35 participating public schools according to enrollment and ethnicity (% Hispanic) and then used block randomisation to assign each school to one of 4 conditions (Mexican American, Black/White, multicultural and control; 8, 9, 8 and 10 schools |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | The anonymisation process linked 24% of the students over all 4 waves, an additional 22% over 3 waves, and another 19% between only 2 of the waves. Altogether, 55% of the respondents had a pretest questionnaire linked to at least 1 of the post‐tests |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Statistically significant differences in racial and socioeconomic conditions, but data adjusted for baseline characteristics |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

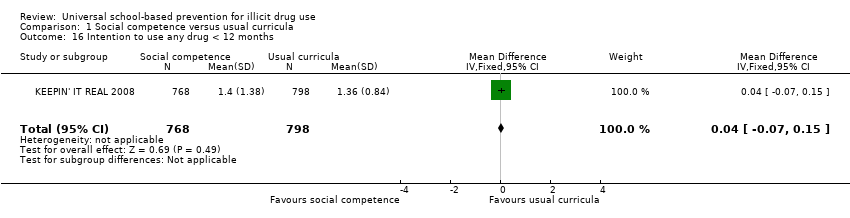

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | At baseline, 1566 5th grade students from 23 public middle schools (81 homerooms) in Phoenix, Arizona (USA). School year 2004 to 2006 | |

| Interventions | Experimental: keepin 'it REAL (kiR) adapted multicultural curriculum for the 5th grade. The 5th grade version uses the same basic curriculum content as the standard 7th grade multicultural version, differing primarily in communication level/format, the concreteness of the presentation of concepts, and the age‐based relevance of the examples. Although the core content of the standard curriculum uses several strategies deemed successful with preadolescent children (narrative, participatory modelling, Social competence approach n = 10 schools Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N of sessions: 12 sessions in 5th grade, 3 to 6 boosters Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: 18 months Control: standard intervention, n = 13 schools | |

| Outcomes | Socio‐demographic characteristics Hypothetical alcohol resistance Students' active decision‐making style Intentions to use substances Parents' anti‐drug injunctive norms Friends' anti‐drug injunctive norms Personal anti‐drug norms Descriptive norms Substance use expectancies Lifetime prevalence of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, inhalants Past month's prevalence of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at the end of the intervention (12 months follow‐up) and at the end of the booster session (18 months) Analysis sample n = 1566, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported Data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 91% of the students who participated in the baseline assessment also participated at wave 2; and 72% of the students who participated in the baseline assessment also participated at wave 3. Schools reported students transferring out at rates of between 10% and 25% (average transfer out rate of 16%), which accounts for much of the attrition between baseline and wave 3 |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | A test of homogeneity of proportions indicated that the 7 student participation patterns did not vary between the 2 study conditions (F(3.58, 78.82) = 0.545, P value = 0.684). Thus, there does not appear to be evidence of differential participation. Although it is possible that the students in the 2 conditions differed with respect to unobserved characteristics, the data presented in Table 1 suggest that they did not differ with respect to some observed characteristics that have been shown to be correlated with substance use among adolescents |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | At baseline 1984 students from 5th grade from 29 public elementary schools in Phoenix, Arizona, 2004 school year | |

| Interventions | Experimental: participants were assigned to 6 conditions: The 5th grade versions use the same basic curriculum content as the 7th grade versions, differing primarily in Social competence approach n = not reported Deliverer: not reported Modality not reported Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: 18 months Control: school's regularly scheduled, substance use prevention programme, n = not reported | |

| Outcomes | Lifetime substance use prevalence (alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, inhalants); past month prevalence; intention to use substances; refusal efficacy; hypothetical alcohol resistance; number of substance use resistance strategies; descriptive substance use norms (scales); personal anti‐drug norms; positive substance use expectancies (scales) | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at 8th grade ‐ wave 6, 48 months after (baseline ‐ W1 at the beginning of the 5th grade = fall 2004; 5th follow‐up ‐ W6 during 8th grade = winter 2007 to 2008) Analysis sample n = 1984, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Student participation fell to 45% of the original sample by the final assessment, with losses concentrated in 3 of the original 29 schools |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 1311 7th grade students from 10 suburban New York junior high schools, USA. 1185 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Life Skills Training Program (LST) is a multicomponent substance abuse prevention programme consisting of 5 major components: cognitive, decision‐making, anxiety, managing, social skills training, self improvement, with the following experimental conditions (factorial design): Social competence approach n = 8 schools Deliverer: teacher, peer (older students) Modality: not reported N of sessions: 20 sessions in 7th grade, 10 sessions for booster Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: 2 school years Control: not reported, n = 2 schools | |

| Outcomes | Smoking status, problem drinking, marijuana use (ever tried, monthly, weekly, daily), cognitive measures, attitudinal measures, personality measures | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at: post‐test (4 months after the pre‐test),12 months after the implementation of the intervention No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis: the absolute numbers of participants in the groups are not given. Authors contacted without reply | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "the 10 schools had been randomly assigned to the five conditions. Two schools were assigned to each experimental condition and two schools were assigned to the control condition" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Attrition at post‐test: 9.6% |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 5954 7th grade students from 56 schools in the New York State (USA), fall of 1985 to 1986 school year 4466 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Life Skills Training Program: a cognitive‐behavioural resistance skills prevention programme, with 3 experimental conditions: Social competence approach Deliverer: teacher, project staff Modality: not reported N of sessions: 15 sessions in 7th grade, 10 sessions for booster in 8th grade and 5 in 9th grade Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: 3 school years Control: as usual, n = 1142 | |

| Outcomes | Monthly and weekly prevalence of cigarette smoking, alcohol, marijuana and other drugs consumption; knowledge attitude; normative beliefs; skills; psychologic characteristics | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at: post‐test (at the end of the intervention), and at 6 years follow‐up (3 years after the end of the intervention) Attrition at post‐test: 25% 782 students were excluded from the analysis sample because of failure to meet the inclusion criteria Attrition after 6 years: 39.6%. Analysis sample: n = 3597 Data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "In a randomized block design, schools were assigned to receive one of the three interventions". School were divided in 3 groups on the basis of the geographic area of New York city. Within each area schools were also divided into 3 groups on the basis of cigarette smoking prevalence rates (high, medium or low) and assigned to the experimental conditions within each group and geographic area |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 25% of the original sample unavailable at 6 years follow‐up. Attrition analysis examining the effect of baseline drug use and condition revealed higher attrition among marijuana users at baseline, among students in control condition and among marijuana users in control condition 40% of the original sample unavailable at 6 years follow‐up. Attrition analysis examining the effect of baseline drug use and condition revealed no differential attrition effect |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | No significant differences for behavioural outcome measures |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Quote: "students were assessed by questionnaires administered by project staff" |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT 6 schools were matched according to demographics and randomly assigned to receive one of 3 interventions | |

| Participants | 757 7th grade students from 6 junior high schools in New York (USA), school year not specified | |

| Interventions | Experimental: 2 experimental conditions: Social competence approach Deliverer: project staff + peer Interactive modality N of sessions: 15 at an average rate of 2 sessions per week in the 7th grade Booster: yes in the 8th grade Duration of the intervention: 18 months Control group: information only, n = 124 | |

| Outcomes | Marijuana use (assessed on a 9‐point scale: never tried, tried but don't use now, less than once a month, about once a month, about 2 or 3 times a month, about once a week, a few times a week, about once a day, more than once a day) Knowledge Intention to use | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test and at 18 months after the end of the intervention Attrition at post‐test: 16%. Analysis sample: n = 639 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Schools were randomly assigned to receive one of the three interventions" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Attrition analysis revealed no significant attrition effect on pretest drinking status; there were slightly more attrition among marijuana users in the control intervention |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | High risk | Culturally focused intervention is targeted only at high‐risk individuals, but it is not reported how high‐risk was defined; moreover in this case only some of the students in the schools randomised to this intervention should have received the intervention (i.e. the high‐risk students) but this information is not provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not provided |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 5222 7th grade students from 29 New York City public schools (USA), school year not specified. 3621 (69%) students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Drug Abuse Prevention Program, teaching drug resistance skills, anti‐drug norms, and facilitating the development of personal and social skills. These skills were taught using a combination of teaching techniques including group discussion, demonstration, modelling, behavioural rehearsal, feedback and reinforcing, and behavioural homework assignments Social competence approach n = 2144 Deliverer: teacher Modality: not reported N of sessions: 15 sessions in 7th grade, 10 sessions for booster in the 8th grade Booster: yes Duration of the intervention: 2 school years Control: programme that was normally in place at New York City schools, n = 1477 | |

| Outcomes | Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, inhalants use; behavioural intentions; normative expectations; drug attitudes and knowledge; social and personal competence Students provided data at the pre‐test and post‐test (grade 7), as well as at the 1‐year follow‐up (grade 8) | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at: post‐test (3 months after the end of the intervention) and 1 year after the end of the intervention Analysis sample n = 3621, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported Data for inclusion in the tables were obtained from authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Blocked randomised design. Prior to randomisation, schools were surveyed and divided into high, medium, or low smoking prevalence. From within these groups, each of the 29 participating schools were randomised to either receive the intervention (16 schools) or be in the control group (13 schools)" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Attrition analysis examining the effect of baseline drug use and condition revealed higher attrition among marijuana users at baseline, and among marijuana users in control condition |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | No significant difference in any substance use variables or gender: there were more black students in the experimental condition and more Hispanic students in the control conditions |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not provided |

| Methods | Randomised pretest and post‐test comparative design (it seems that individuals are sample unit) | |

| Participants | 170 Thai high school students from grades 7 to 12, years not specified | |

| Interventions | Experimental: LST programme provided students with information and skills specifically related to drug and tobacco use, such as the effects of drugs, self awareness skills, decision‐making and problem‐solving skills, stress and coping skills, and refusal skills Social competence approach n = 85 Deliverer: not reported Interactive modality N of sessions: 10 Booster: no Duration of the intervention: not reported Control: tobacco and drug education curriculum normally provided, n = 85 | |

| Outcomes | Knowledge about the health consequences of tobacco and drug use Attitudes toward tobacco and drug use Life skills, refusal, decision‐making and problem‐solving skills Tobacco and drug use frequency in the past 2 months | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at: post‐test (6 months after the end of the intervention) Analysis sample n = 170, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported Attrition at post‐test not reported No data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | The results revealed no significant differences between the control and the intervention groups at pretest |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 36 public schools from 2 South African provinces, KwaZulu‐Natal and the Western Cape, school year not specified. 5266 students completed baseline survey. | |

| Interventions | Experimental : Keep Left South African version and Life Skill Training South African version: decision‐making framework, stress management, resisting peer pressure Social competence approach Group 1: Keep Left South African version; n = 12 schools, 1978 students ‐Group 2: LST South African version; n = 12 schools, 1717 students Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N of sessions: 16 sessions for Keep Left and 16 sessions for LST Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 2 school years (8th grade and 9th grade) Control: usual tobacco and substance use education, n = 12 schools, 1571 students | |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome was past month use of cigarettes; secondary outcomes were: daily marijuana and hard drug use, daily binge drinking | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at: post‐test 1 (after 1 year, at the end of the 8th grade) and at post‐test 2 (after 2 years, at the end of the 9th grade) Analysis sample at post‐test 2 n = 3267, n intervention group at post‐test 2 = 2256, n control group at post‐test 2 = 1011 Data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Schools were then randomly selected within each ethnicity, size and SES strata. The target sample was 36 or 12 per experimental group |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Students completed questionnaires on 3 occasions: (1) baseline at the beginning of 8th grade, (2) post‐test 1 at the end of 8th grade, and (3) post‐test 2 at the end of9th grade. For the 2 post‐test assessments, only individuals who were in the school at the beginning of grade 8 and who completed the baseline evaluation were asked to complete questionnaires. Thus, there was selective attrition in the study |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | At baseline, the 3 intervention groups did not differ on any of the socio‐demographic or substance |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 416 students aged 16 to 19 years old recruited in 12 London Further Education colleges without regard to substance use status. The response was encouraging with 12 out of 21 colleges approached agreeing to participate. Age 16 to 19 years was adopted as the sole inclusion criterion, and there were no formal exclusion criteria | |

| Interventions | Experimental: motivational Interview: highly individualised intervention. Its aim is to help the participant explore their own behaviour. Particular emphasis is given to perceptions of risk and problem recognition, concerns and consideration of change, and also to the activity of the practitioner in directing attention towards the resolution of ambivalence Deliverer: not reported Interactive modality N of sessions: 1 Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 1 hour Control group: "Drug Awareness" (DA): 16‐question quiz on the effects of cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and cannabis use, followed by further discussion components and the provision of leaflets giving accurate information on the effects of target drugs | |

| Outcomes | Prevalence, initiation and cessation rates for cannabis use | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at 3 and 12 months follow‐up Attrition: 3 months: 11%, 12 months: 16.5% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Computerised randomisation was undertaken by the local Clinical Trials Unit and decisions were communicated by telephone to researchers after recruitment and baseline data collection on an individual college basis to preserve allocation concealment. We stratified allocation by college, so that equivalent numbers of groups recruited from any one college would be allocated to each study condition." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Computerised randomisation was undertaken by the local Clinical Trials Unit and decisions were communicated by telephone to researchers after recruitment and baseline data collection on an individual college basis to preserve allocation concealment. We stratified allocation by college, so that equivalent numbers of groups recruited from any one college would be allocated to each study condition." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Attrition was not differential between the study groups |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | Randomisation successfully created baseline equivalence between groups |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 473 students from 7th and 9th grade attending 2 junior high schools in a suburban community in Northern California (USA), during second semester of the academic year 1980 to 1981. 399 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Napa Project focus on motivation and decision‐making skills, personal goals, assertiveness, knowledge Social competence approach n = 237 Deliverer: project staff Interactive modality N of sessions: 12 sessions from February through May 1981 Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 4 months Control: programme that was normally in place at New York City schools, n = 236 | |

| Outcomes | Any drug Drug knowledge, general drug attitude, alcohol benefits, pot benefits, alcohol costs, pot costs, soft attitudes, soft peer attitudes, soft peer use, alcohol involvement, cigarette involvement, pot involvement, pill benefits, pill cost, hard peer attitude, hard peer use, hard attitude | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at: post‐test (May 1981, at the end of the intervention) and at 5 months (October 1981) Analysis sample n = 352, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "classes were paired on pretest attitudes and involvement in alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use. One class in each pair was then randomly assigned to receive the experimental intervention and the other to the control group" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Methods | Cluster‐RCT | |

| Participants | 7846 participants, first 3 years of 48 schools (24 experimental and 24 control), Hong Kong | |

| Interventions | Experimental intervention: Positive Adolescent Training through Holistic Social Programmes. There are 2 tiers of programmes in the Project PATHS. Both tiers are developed with reference to 15 positive youth development constructs, including bonding, resilience, social competence, recognition of positive behaviour, emotional competence, cognitive competence, behavioural competence, moral competence, self determination, self efficacy, clear and positive identity, beliefs in the future, prosocial involvement, prosocial norms and thriving. An important feature of the Project PATHS is its systematic evaluation approaches (e.g. interim evaluation, focus group interview, survey on subjective and objective outcomes, programme implementers' evaluation, student weekly diary, etc.), which enable researchers to examine the effectiveness of the programme thoroughly= (n = 4049) Other approach Deliverer: teacher and social worker Interactive Number of sessions: 120 (40 every school year) Booster: only a parallel tier 2 programme for students with special needs Duration of intervention: 36 months | |

| Outcomes | Use of drugs: composite score of illegal drug use (ketamine, cannabis, ecstasy, heroine) Likert scale (0 to 7) | |

| Notes | Process evaluation year 1 to 3 (wave 1 to 6). 3 and 12 months after the end (wave 7, 8) Attrition Wave (W) 1, W2, W3, W4, W5, W6, W7, W8 Experimental: 4049, 3734, 3174, 2999, 3119, 3006, 2879 (71%), 2852 (70%) Control: 3797, 3654, 3765, 3698, 3757, 3727, 3669 (96%), 3640 (96%) No data suitable for meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Eighty schools, representative of schools in the three region areas, were randomized to either control or intervention arm. Five schools (6.3%) from the control arm withdrew before the baseline survey and were not replaced. There were no differences found between the schools that withdrew and participating schools." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Eighty schools, representative of schools in the three region areas, were randomized to either control or intervention arm. Five schools (6.3%) from the control arm withdrew before the baseline survey and were not replaced. There were no differences found between the schools that withdrew and participating schools." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | High attrition in the experimental group (30%) and unbalanced (only 4% in the control group) |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Quote: "With schools being the units of analysis, results indicated that the 19 experimental schools and 24 control schools did not differ in school characteristics in terms of banding (i.e., categorizing based on students academic competence), geographic district, religious affiliation, sex ratio of the students, Data not reported for substance use at baseline |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 283 junior and senior high school students (volunteers) from the public schools of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (USA). 1979 to 1980 and 1980 to 1981 school years | |

| Interventions | Experimental: PAY programme (Positive Alternatives for Youth), aimed to increase alternatives to drug abuse, such as personal awareness, interpersonal relations, self reliance development, vocational skills, aesthetic and intellectual experiences, social‐political involvement, sexual expression, meditation, spiritual‐mystical experiences and creative experiences Social competence approach n = 160 Deliverer: project staff and teacher Interactive modality. N of sessions: 48 sessions during 2 school years (1979 to 1980 and 1980 to 1981) Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 6 months Control: no treatment, n = 123 | |

| Outcomes | Drug and alcohol use, activities participation, feelings and remedies, marijuana and alcohol involvement, attitudes and perceptions of one's social skills, peer pressure resistance, self esteem, future orientation, stress management, attitudes towards drugs and alcohol, responsible use, activity attitudes | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at: post‐test 1 (during the spring semester of 1980) and at post‐test 2 (at the end of the programme, during the spring semester of 1980) Analysis sample at post‐test 2 n = 105, n intervention group 58, n control group 50 Attrition at post‐test (first year): 14.4% for the experimental group, 10.9% for the control group No data suitable for inclusion in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "students were randomly assigned to either the PAY alternative classes or to a no treatment control group" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Drop‐out balanced in numbers across intervention groups but reasons for dropping out and characteristics of students who dropped out compared with characteristics of students who remained are not reported |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Unclear risk | Information not reported, apart from sex and ethnicity |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Questionnaires were compiled by participants using an anonym code and in a manner that ensured privacy without access by teachers, parents or project staff |

| Methods | Matched‐pair, cluster‐randomised, controlled design, | |

| Participants | 1714 first or second grade children at baseline from 20 public elementary (kindergarten to 5th or 6th grade) schools on 3 Hawaiian islands. Our study followed students who were in 1st or 2nd grade at baseline (the 2001 to 2002 academic year) and who stayed in the study schools through 5th grade (the 2005 to –2006 academic year for the first grade cohort, and the 2004 to 2005 academic year for the second grade cohort) | |

| Interventions | Experimental: the Positive Action programme is a multicomponent school‐based social and character development programme designed to improve academics, student behaviours and character. Lessons are grouped into 6 major units: self concept, mind and body positive actions (e.g. nutrition, physical activity, decision‐making skills, motivation to learn), social and emotional actions for managing oneself responsibly (e.g. emotion regulation, time management), getting along with others (e.g. empathy, respect, treating others as one would like to be treated), being honest with yourself and others, and self improvement (e.g. goal‐setting, courage to try new things, persistence) Social competence approach 10 schools, N = 976 Deliverer: teacher Interactive modality N. of session: 140 per year over 5 years (total 700) Booster: yes Control: business as usual 10 schools , N = 738 | |

| Outcomes | Lifetime prevalence of substance use, self reported (N = 1714) and observed by teacher (N = 1225) (yes/no and scale) | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test Attrition: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Students who left study schools during the study period were dropped from the study, and students who joined study schools during the study period were added to the study (without collecting baseline data). Thus, our study also included students who entered the schools at any year during the course of the study and who were in 5th grade at the end of the study |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | No significant differences (P value ≥ 0.05) were observed between reports from control and intervention schools, |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Of the 512 adolescents recruited into the study (students attending 2 public high schools in northeast Florida during fall 2008), 93.6% (n = 479) participated in the baseline data collection, with 19 students grade‐ineligible and 14 students absent from school | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Project Active 9‐item life skills screen assessing target health behaviours, a one‐on‐one consultation with slides presenting positive image feedback tailored to screen results, a set of concrete behavioural recommendations for enhancing future fitness, and a personal fitness goal‐setting and commitment strategy linking positive image attainment with specific health behaviour change. Intervention content and strategies were based on the Behaviour‐Image Model (n = 237) Deliverer: not reported Passive modality N of sessions: 1 Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 1 hour Control group: 15‐page booklet titled: "What Everyone Should Know ABOUT WELLNESS",which included information and illustrations about smoking, alcohol and drug use avoidance, exercise types and benefits, eating nutritious foods, managing stress, getting adequate sleep and maintaining a positive attitude (n = 242) | |

| Outcomes | Frequency and quantity of marijuana use, scored as 30‐day frequency (ranging from 1 = 0 days through 11 = 28 to 30 days) and 30‐day quantity (ranging from 1 = 0 marijuana times used per day through 12 = 31 or more times using marijuana) | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at 3 months follow‐up Attrition: 6% | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A randomised controlled trial was conducted using a within‐school design at 2 schools. Participants were |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Most participants (94.1%) successfully completed the post‐intervention data collection. Of those lost to follow‐up, 24 participants (85.7%) moved away from school and 4 (14.3%) were lost due to repeated absence from school, resulting in a total of 451 participants. No differences were found in the proportion of those who dropped out between treatment groups or participating schools |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | No differences were found for any of the socio‐demographic or target health behaviour measures between treatment groups at baseline |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 140 students attending a school in Hackney (London), aged 7 to 10 years, school year not specified. 120 students completed baseline survey | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Project CHARLIE (Chemical Abuse Resolution Lies in Education) is based on lessons focused on increase of self esteem, decision‐making power, resistance skills and knowledge, Social competence approach n = 65 students Deliverer: teacher Modality. not reported N of sessions: 40 sessions during 2 school years (1979 to 1980 and 1980 to 1981) Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 12 months Control: no intervention, n = 55 students | |

| Outcomes | Resistance and decision‐making skills | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at post‐test (at the end of the intervention) Analysis sample at post‐test 2 n = not reported, n intervention group not reported, n control group not reported. Attrition: 10.9% in the intervention group Data suitable for inclusion in meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "all the children attending the selected two forms entry junior school were randomly selected to receive the Project Charlie" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Reasons for drop‐out not reported |

| Similarity of groups at baseline | Low risk | No significant differences in socio‐demographic characteristics between groups |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "pre and post‐testing was carried out by one of the authors with no involvement in the teaching of Project Charlie and commissioned to carry out the independent evaluation" |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | A total of 604 participants, 335 9th grade and 269 11th grade students from a suburban high school in northeast Florida, participated in this study | |

| Interventions | Experimental: Project Sport The project consisted of a brief consultation and in‐person health behaviour screen, a one‐on‐one consultation, a take‐home fitness prescription targeting adolescent health promoting behaviours and alcohol use risk and protective factors, and a flyer reinforcing key content provided during the consultation mailed to the home. These brief prevention technologies Deliverer: project staff Passive modality N of sessions: 1 Booster: no Duration of the intervention: 1 day Control group: minimal intervention consisting of a wellness brochure provided in school and a pamphlet about teen health and fitness mailed to the home (n = 302) | |

| Outcomes | Drug use behaviours measured included 30‐day frequency of cigarette smoking and marijuana use, paralleling the alcohol frequency measure. Similarly, measures of cigarette and marijuana stage of initiation were taken, which also corresponded to the measure of alcohol use initiation. Mediators evaluated only for alcohol | |

| Notes | Outcome assessed at 3 and 12 months after the end of the intervention Attrition: 15% at 12 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A randomised controlled trial was conducted, with participating students randomly assigned within grade levels (9th and 11th grades) by computer to either the intervention or control group |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A randomised controlled trial was conducted, with participating students randomly assigned within grade levels (9th and 11th grades) by computer to either the intervention or control group |