Antibiotika gegen akute Mittelohrentzündung bei Kindern

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, computer‐generated random numbers Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 126 children (N = 121 children included in analysis) Age ‐ between 6 months and 12 years Inclusion criteria ‐ recurrence of acute otitis media (AOM) characterised by a (sub)acute onset, otalgia and otoscopic signs of middle‐ear infection within 4 weeks to 12 months of the previous attack Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment < 4 weeks prior to randomisation, previous participation in this study, contraindication for penicillin, serious concurrent disease that necessitated antibiotic treatment Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ amoxicillin/clavulanate (weight tailored dose) for 7 days; N = 70 (N = 67 included in analysis) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ treatment failure (i.e. presence of otalgia or fever > 38 °C or both at 3 days) Assessment by (blinded) general practitioner at 3 days on the presence or absence of fever (> 38 °C) and otalgia and 14 days on the presence or otorrhoea Assessment by otorhinolaryngologist at 1 month of otoscopy, tympanometry and in children > 3 years of age an audiogram | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Treatment allocated by otolaryngologist (independent to trial personnel); treatment code placed in sealed envelopes |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Identical taste and appearance to amoxicillin/clavulanate and placebo not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up ‐ treatment: N = 3 (4%) and placebo: N = 2 (4%) due to loss of their registration forms |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, computer‐generated random numbers Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ not described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 232 children Age ‐ between 3 and 10 years Inclusion criteria ‐ acute earache and at least 1 abnormal eardrum Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment or acute otitis media (AOM) < 2 weeks prior to randomisation, strong indication for antibiotic treatment according to general practitioner, contraindication for amoxicillin, serious chronic conditions Baseline characteristics ‐ slight imbalance in gender (boys treated with antibiotics versus boys treated with placebo = 52% versus 42%) and figure 1 appears to demonstrate that fewer children were crying at baseline (0 hours) in the amoxicillin arm compared with the placebo arm, suggesting a failure of randomisation | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ amoxicillin 250 mg 3 times daily for 7 days; N = 114 (N = 114 included in analysis for short‐term outcome) | |

| Outcomes | Main outcomes were divided into short‐term, middle‐term and long‐term: Short‐term ‐ (a) duration of symptoms; (b) use of analgesics (assessed by weighing bottles); (c) clinical signs at 1 week; (d) incidence of complications; (e) treatment failure (i.e. second‐line antibiotics were required) Middle‐term ‐ (a) tympanometry findings at 1 and 3 months Long‐term ‐ (b) number of AOM episodes in 12 months; (b) number of specialist referrals Home visits by researcher at day 1, days 4 to 6 and general practitioner visit at day 7 Symptom diary kept by parents for 21 days | |

| Notes | It is not clear whether the "discharging ears" in Table 1 should be included as perforations, we now included the number of perforations as summarised in Table 2 in our analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was carried out independently of the investigators; randomisation code was kept sealed and was unknown to any of the participants in the study |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes; baseline characteristics ‐ imbalance for gender and crying |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Each bottle was identified only by number |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up ‐ not described; all randomised patients included in short‐outcome analysis |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, computerised 2 block randomisation Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 240 children (N = 212 children included in analysis) Age ‐ between 6 months and 2 years Inclusion criteria ‐ acute otitis media (AOM) defined as infection of the middle ear of acute onset and a characteristic eardrum picture (injection along the handle of the malleus and the annulus of the tympanic membrane or a diffusely red or bulging eardrum) or acute otorrhoea. In addition 1 or more symptoms of acute infection (fever, recent earache, general malaise, recent irritability) Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment < 4 weeks prior to randomisation, contraindication for amoxicillin, comprised immunity, craniofacial abnormalities, Down's syndrome or being entered in this study before Baseline characteristics ‐ slight imbalance in the prevalence of recurrent AOM, regular attendance at a daycare centre and parental smoking; logistic regression was used to adjust for these imbalances | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ amoxicillin suspension 40 mg/kg/day 3 times daily for 10 days; N = 117 (N = 107 included in analysis for short‐term outcome) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ persistent symptoms at day 4: assessed by the doctor and defined as persistent earache, fever > 38 °C, crying or being irritable. Additionally, prescription of another antibiotic because of clinical deterioration before the first follow‐up visit was to be considered a persistent symptom Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) clinical treatment failure at day 11 (i.e. persistent fever, earache, crying, being irritable or no improvement of tympanic membrane (including perforation); (b) duration of fever, pain or crying; (c) mean number of doses analgesics given; (d) adverse effects mentioned in diaries; (e) percentage of children with middle‐ear effusion at 6 weeks (i.e. combined otoscopy and tympanometry) Follow‐up visits at the GP's clinic were scheduled at day 4 and 11; home visit at 6 weeks by the researcher collecting data of symptoms, referrals and both otoscopy and tympanometry was performed Parents were instructed to keep a symptom diary for 10 days | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerised 2 block randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was carried out independently of the investigators; randomisation code was kept in pharmacy of the University Medical Centre Utrecht |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ slight imbalance, logistic regression was used to adjust for imbalances in prognostic factors |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Placebo suspension with same taste and appearance as amoxicillin |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up/exclusion from analysis (received other antibiotics or had grommets inserted) ‐ treatment: N = 10 (9%) and placebo: N = 18 (15%). However, for primary analysis of symptoms at day 4 all randomised patients were included |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, pre‐determined code, which was unknown to physician; method of random sequence generation unclear Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ described, unclear from which treatment group patients were excluded Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 106 children (N = 89 children included in analysis; N = 12 children were excluded because they did not adhere to the double‐blind protocol; N = 5 children lost to follow‐up or excluded because of persistent fever, development of complication requiring antibiotic treatment or if group A streptococci was cultured from the middle ear) Age ‐ between 2 months and 5.5 years Inclusion criteria ‐ AOM based on otoscopic findings; most of the cases had bulging membrane with loss of normal light reflex and landmarks, in a few the eardrum was only diffusely red Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment < 10 days prior to randomisation, associated bacterial infection requiring antibiotic treatment, rupture of tympanic membrane, contraindication for study drugs Baseline characteristics ‐ not described | |

| Interventions | Tx 1 ‐ ampicillin 100 mg/kg/day 4 daily for 10 days; N = ? (N = 30 included in analysis) Tx 2 ‐ pheneticillin 30 mg/kg/day 4 daily and sulfisoxazole 150 mg/kg/day 4 daily for 10 days; N = ? (N = 32 included in analysis) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ early improvement defined as defervescence and decrease of symptoms at 24 to 72 hours Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) late improvement defined as resolution of symptoms and normal tympanic membrane at 14 to 18 days, (b) bacteriological cultures | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Pre‐determined code, which was unknown to physician; method of random sequence generation unclear |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear, baseline characteristics ‐ not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Identical taste and appearance to antibiotics and placebo not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Reasons described, unclear from which treatment group patients were excluded |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, stratified block randomisation with computer‐generated randomisation lists Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 291 (N = 291 included in analysis) Age ‐ between 6 months and 2 years Inclusion criteria ‐ children needed to have received at least 2 doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and to have acute otitis media (AOM) as defined on the basis of 3 criteria: (a) the onset (i.e. within the preceding 48 hours) of symptoms that parents rated with a score of at least 3 on the acute otitis media ‐ severity of symptoms (AOM‐SOS) scale (on which scores range from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms), (b) the presence of middle‐ear effusion and (c) moderate or marked bulging of the tympanic membrane or slight bulging accompanied by either otalgia or marked erythema of the membrane All the study clinicians were otoscopists who had successfully completed an otoscopic validation programme Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment < 96 hours prior to randomisation, concomitant acute illness (e.g. pneumonia) or a chronic illness (e.g. cystic fibrosis), contraindication to amoxicillin, presence of otalgia for more than 48 hours, perforation of the tympanic membrane Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ amoxicillin‐clavulanate 90‐6.4 mg/kg daily in 2 doses for 10 days; N = 144 (N = 139 were assessed at day 4 to 5) At each visit children were categorised as having met the criteria for either clinical success or clinical failure Children who met the criteria for clinical failure were treated with a standardised 10‐day regimen of orally administered amoxicillin (90 mg/kg daily) and cefixime (8 mg/kg daily) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes ‐ (a) time to resolution of symptoms (i.e. time to the first recording of an AOM‐SOS score of 0 or 1 and the time to the second of 2 successive recordings of that score; (b) symptom burden over time (i.e. mean AOM‐SOS score over time each day for the first 7 days of follow‐up and groups' weighted mean scores for that period) Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) clinical failure at day 4 to 5; (b) clinical failure at day 10 to 12; (c) use of acetaminophen (paracetamol); (d) occurrence of adverse events; (e) nasopharyngeal colonisation rates; (f) use of healthcare resources; (g) relapses Clinical failure was defined at or before the day 4 to 5 visit as either a lack of substantial improvement in symptoms, a worsening of signs on otoscopic examination, or both and at the day 10 to 12 visit as the failure to achieve complete or nearly complete resolutions of symptoms and otoscopic signs, without regard to the persistence of resolution of middle‐ear effusion. Once a child had met the criteria for clinical failure, he or she remained in that category for the analysis Daily symptoms were assessed with the use of a structured interview of 1 of the child's parents until the first follow‐up visit; visits were scheduled at day 4 or 5, day 10 to 12 (end of treatment) and at day 21 to 25 Patients were asked to complete a diary twice a day for 3 days and once a day thereafter | |

| Notes | This study did not report pain data that could be used for the review comparing antibiotics with placebo | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified block randomisation with computer‐generated randomisation lists |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A pharmacist (independent of the trial team) provided masked study medication bottles with amoxicillin/clavulanate or placebo |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Placebo with same taste and appearance as amoxicillin‐clavulanate |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Children not assessed at day 4 to 5 ‐ treatment: N = 5 (3%) and placebo: N = 5 (3%). All randomised patients included in analysis |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, method of randomisation not described Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ not described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 280 children Age ‐ 2.5 years or younger Inclusion criteria ‐ acute otitis media (AOM) as clinically diagnosed by the participating paediatricians Exclusion criteria ‐ if researchers felt that parents would not accept diagnostic aspiration, when condition of the patient required immediate antibiotic treatment Baseline characteristics ‐ not described | |

| Interventions | Tx 1 ‐ erythromycin estolate 125 mg/5 mL ‐ triple sulphonamide suspension 0.5 g/5 mL; N = 80 Tx 2 ‐ ampicillin 250 mg/5 mL; N = 36 Tx 3 ‐ triple sulphonamide suspension 0.5 g/5 mL; N = 23 Tx 4 ‐ erythromycin estolate 125 mg/5 mL; N = 25 C 2 ‐ placebo ‐ 4 parts Kaopectate and 1 part acetaminophen (paracetamol, Tylenol) plus food colouring; N = 83 | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes ‐ (a) presence or absence of exudate while on medication; (b) bacteriological findings of the exudate when present; no patient‐relevant outcomes were described At baseline and before treatment was started, the middle‐ear exudate was aspirated. The decision whether to collect exudate on the first repeat visit was made with no knowledge of the drug regimen to which the patient had been assigned | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was performed by a collaborating pharmacist |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear, baseline characteristics ‐ not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Identical taste and appearance to amoxicillin/clavulanate and placebo not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up ‐ not described |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, stratified randomisation, method of randomisation not described Concealment of allocation ‐ unclear, method not described Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ not described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 536 children (representing 1049 non‐severe acute otitis media (AOM) episodes; 980 non‐severe AOM episodes included for primary analysis) Setting ‐ secondary care: children's hospital and a private paediatric practice in Pittsburgh (USA) Inclusion criteria ‐ AOM based on presence of middle‐ear effusion, as determined otoscopically, in association with specified symptoms of acute middle‐ear infection (fever, otalgia or irritability), or signs of acute infection (erythema or white opacification, or both, accompanied by fullness or bulging and impaired mobility), or both Exclusion criteria ‐ children who recently received antibiotics, who had potential complicating or confounding conditions (e.g. eardrum perforation, asthma or chronic sinusitis) Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Children were enrolled for a 1‐year period. At entry each child was assigned randomly to a treatment regimen that specified consistent treatments for episodes of non‐severe and severe AOM based on severity of otalgia and the presence of fever (> 39 °C orally or > 39.5 °C rectally within the 24‐hour period before presentation) Non‐severe AOM episodes were treated with: Tx ‐ amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/day 3 times daily for 14 days; N = 522 (N = 488 included in primary analysis) C ‐ placebo for 14 days; N = 527 (N = 492 included in primary analysis) Severe AOM episodes in children aged < 2 years were treated with: Tx 1 ‐ amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/day 3 times daily for 14 days Tx 2 ‐ amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/day 3 times daily for 14 days and myringotomy Severe AOM episodes in children aged ≥ 2 years were treated with: Tx 2 ‐ amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/day 3 times daily for 14 days and myringotomy Tx 3 ‐ placebo and myringotomy | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ initial treatment failure: in non‐severe episodes this was the case when either otalgia, fever or both was present more than 24 hours after treatment was initiated and when 48 hours or more after initial treatment was initiated the child's temperature reached 38 °C orally or 38.5 °C rectally or an otalgia score of ≥ 6 was present Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) recurrent AOM defined as the development of AOM 15 days or more after the initiation of treatment for a preceding episode, (b) new episodes of otitis media with effusion defined by otoscopy and tympanometry findings After initial visits, children were followed up by telephone to identify those with persistent symptoms and children younger than 2 years of age were re‐examined within 48 to 72 hours Follow‐up visits were scheduled routinely after 2 and 6 weeks after initial treatment and monthly thereafter | |

| Notes | We included only the non‐severe AOM episodes in this review (N = 1049 of which 980 were included for primary analysis); children experiencing non‐severe AOM episodes were randomly allocated to either antibiotics or placebo | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Identical taste and appearance to amoxicillin and placebo not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Follow‐up/exclusion of non‐severe episodes for short‐term outcome ‐ treatment: N = 34 (7%) and placebo: N = 35 (7%). Reasons not described |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, method of randomisation not described Concealment of allocation ‐ unclear; method not described Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ not described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 142 children Age ‐ between 0 to 15 years Inclusion criteria ‐ at least 1 eardrum had to show redness and loss of landmarks Exclusion criteria ‐ predominant respiratory symptoms, if allergy appeared to be a significant factor or if rupture of the eardrum had occurred Baseline characteristics ‐ not described | |

| Interventions | Tx 1 ‐ penicillin G 250 mg/m2/day 4 times daily (approximately 33 mg/kg/day) for at least 7 days; N = 45 Tx 2 ‐ ampicillin 250 mg/m2/day 4 times daily (approximately 33 mg/kg/day) for at least 7 days; N = 49 | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes ‐ (a) treatment failure (i.e. either deterioration or no improvement observed at day 7) (b) relapses Results were evaluated at 7 days, except in cases where the ear inflammation was severe and the child appeared sufficiently ill (toxic) to warrant further examination 24 to 48 hours after treatment initiation Children in the control group were subjected to very close scrutiny, especially during the first 48 hours and particularly when severe involvement was evident (high risk of detection bias) | |

| Notes | Open‐label trial comparing immediate antibiotics (penicillin G and ampicillin) versus expectant observation It was unclear whether otalgia played an important role in the definition of treatment failure Data on relapses: N = 126 included in analysis, no crude numbers for separate treatment groups provided | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Other bias | High risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear, baseline characteristics ‐ not described, high risk of detection bias due to different follow‐up strategies between treatment groups |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Open‐label trial, outcome assessment not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up ‐ not described for short‐term outcome. Loss to follow‐up for long‐term outcome (acute otitis media (AOM) relapses) ‐ N = 16 (11%), no crude numbers of separate treatment groups provided |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, computer‐generated randomisation sequence Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 531 children (N = 512 children included in analysis; N = 19 were excluded post hoc due to inappropriate randomisation (N = 4) or alternative clinical diagnosis (N = 15)) Age ‐ between 6 months and 5 years Inclusion criteria ‐ new onset (< 4 days) of symptoms referable to the upper respiratory tract and either ear pain or fever (> 38 °C). In addition, all patients had to have evidence of middle‐ear effusion, defined by ≥ 2 of the following signs: opacity, impaired mobility on the basis of pneumatic otoscopy and redness or bulging (or both) of the tympanic membrane Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment < 2 weeks prior to randomisation, contraindication to amoxicillin or penicillin or sensitivity to ibuprofen or aspirin, presence of otorrhoea, co‐morbid disease such as sinusitis or pneumonia, prior middle‐ear surgery, placement of a ventilation tube, history of recurrent acute otitis media (more than 4 episodes in 12 months), compromised immunity, craniofacial abnormalities, or any chronic or genetic disorder Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ amoxicillin suspension (60 mg/kg) 3 times daily for 10 days; N = 258 (N = 253 included in analysis for day 3) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ clinical resolution of symptoms, defined as absence of receipt of an antimicrobial (other than amoxicillin in the treatment group) at any time during the 14‐day period. The initiation of antimicrobial therapy was based on persistence or worsening of symptoms, fever or irritability associated with otoscopic signs of unresolving AOM, or development of symptoms indicative for mastoiditis or invasive disease Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) presence of symptoms (i.e. fever, pain, irritability, vomiting, activity level) on days 1, 2 and 3; (b) number of analgesic doses, codeine doses on days 1, 2 and 3; (c) occurrence of any rash or diarrhoea in the 14 days after randomisation; (d) presence of middle‐ear effusion assessed by tympanometry at 1 and 3 months after diagnosis The parents were contacted on days 1, 2 and 3 after randomisation and once between day 10 and day 14 for administration of a standard questionnaire. If the parents or research assistant felt that the symptoms were not improving or were worsening, a medical reassessment was advised and the child was seen by a physician in the emergency department or clinic or by the paediatrician The child was clinically assessed at 1 month and 3 months after randomisation to determine the number of subsequent episodes of acute otitis media (AOM) and to undergo tympanometry | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomisation sequence stratified by study centre and age using random‐permuted blocks of sizes 4 and 6 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation sequence was kept under secure conditions and was accessible only by the trial pharmacist |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Placebo was similar to amoxicillin with regard to appearance and taste and was dispensed in identical opaque bottles, which were numbered sequentially |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up at day 3 ‐ treatment: N = 5 (2%) and placebo: N = 8 (3%) |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, method of randomisation not described Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 315 children (N = 285 children included in analysis) Age ‐ between 6 months and 10 years Setting ‐ general practice; 42 general practitioners in 3 health authorities in south‐west England Inclusion criteria ‐ acute otalgia and otoscopic evidence of acute inflammation of the eardrum (dullness or cloudiness with erythema, bulging or perforation). When children were too young for otalgia to be specifically documented from their history (under 3 years old) then otoscopic evidence alone was a sufficient entry criterion Exclusion criteria ‐ otoscopic appearances consistent with crying or a fever alone (pink drum alone), appearances and history more suggestive of otitis media with effusion and chronic suppurative otitis media, serious chronic disease (such as cystic fibrosis, valvular heart disease), use of antibiotics < 2 weeks prior to randomisation, previous complications (septic complications, hearing impairment) and if the child was unwell to be left to wait and see (e.g. high fever, floppy, drowsy, not responding to antipyretics) Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ immediate treatment with antibiotics: amoxicillin syrup 125 mg/5 mL 3 times daily for 7 days (children who were allergic to amoxicillin received erythromycin 125 mg/5 mL 4 times daily; N = 151 (N = 135 included in analysis) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes ‐ (a) duration of symptoms (i.e. earache, ear discharge, night disturbance, crying); (b) daily pain score; (c) episodes of distress; (d) spoons of paracetamol used; (e) use of antibiotics Doctors were asked to provide information on days of illness, physical signs and antibiotic prescribing; parents were asked to complete a daily symptom diary | |

| Notes | Open‐label trial comparing immediate versus delayed antibiotic prescription (prescription provided but advised to fill only if symptoms did not improve or worsened) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed, numbered, opaque envelopes |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Open‐label trial, outcome assessment not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up/exclusion from analysis (intervention ineffective, did not use antibiotics or did not delay) ‐ treatment: N = 16 (12%) and placebo: N = 14 (9%); comparison of the baseline information for the 3 types of responders (those who provided diaries, those who gave information by telephone and those from whom no diary information could be collected) revealed no evidence of significant bias between treatment groups or between patients by age or severity of symptoms |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, computer‐generated randomisation sequence Concealment of allocation ‐ unclear; method not described Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 223 children (N = 218 children included in analysis at day 12) Age ‐ between 6 months and 12 years Setting ‐ secondary care: paediatric clinic of University of Texas Medical Branch (USA) Inclusion criteria ‐ children were required to have (a) symptoms of ear infection; (b) otoscopic evidence of acute otitis media (AOM), including middle‐ear effusion; (c) non‐severe AOM Exclusion criteria ‐ co‐morbidity requiring antibiotic treatment, anatomic defect of ear or nasopharynx, allergy to study medication, immunologic deficiency, major medical condition and/or indwelling ventilation tube or draining otitis in the affected ear(s) Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ immediate treatment with antibiotics: oral amoxicillin 90 mg/kg/day twice daily for 10 days; N = 112 (N = 110 included in analysis at day 12) Children in the control group with AOM failure or recurrence received oral amoxicillin 90 mg/kg/day; children in Tx group with AOM failure or recurrence received amoxicillin‐clavulanate (90 mg/kg/day of amoxicillin component) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes ‐ (a) parent satisfaction with AOM care; (b) resolution of AOM symptoms after treatment, including number of doses of symptom medication given; (c) AOM failure (days 0 to 12) or recurrence (days 13 to 30) defined as attending to the paediatrician clinic with acute ear symptoms, an abnormal tympanic membrane, or an AOM severity score higher than that at enrolment; (d) nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains resistant to antibiotics Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) minor adverse events caused by medication (e.g. allergy, diarrhoea and candidal infection); (b) serious AOM‐related adverse events (e.g. invasive pneumococcal disease, mastoiditis, bacteraemia, meningitis, perforation of the tympanic membrane, hospitalisation and emergency ear surgery; (c) parent‐child quality of life measures related to AOM Parents were instructed to complete a symptom diary from day 1 to 10 and a satisfaction questionnaire on day 12 and day 30; routine follow‐up appointments for data collection were scheduled for day 12 and day 30. Patient‐initiated visits were scheduled on request by the parents for children who seemed to not be responding to treatment | |

| Notes | Investigator‐blinded trial comparing immediate antibiotic prescribing versus expectant observation (no prescription provided) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomisation sequence |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Investigator‐blinded study, parents not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up at day 12 ‐ treatment: N = 2 (2%) and expectant observation: N = 3 (3%) |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, method of randomisation not described Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ reasons described, unclear from which treatment group patients were excluded Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 158 children (N = 149 included in analysis) Age ‐ between 1 and 10 years Inclusion criteria ‐ earache for 1 to 24 hours. The diagnosis was made if the child cried because of pain and if the tympanic membrane appeared to be red and inflamed Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment < 4 weeks prior to randomisation, other treatment apart from acetylsalicylic acid already commenced, secretion in the external ear, suspected chronic otitis media, treatment for secretory otitis media within last 12 months, concurrent disease (e.g. pneumonia or severe tonsillitis), suspected penicillin allergy Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ penicillin 50 mg/mL 4 times daily; children aged 1 to 2 years: 10 mL daily, children between 3 and 5 years: 20 mL daily, children between 6 and 10 years: 30 mL daily for 7 days; N = ? (N = 72 included in analysis) | |

| Outcomes | Main outcomes: (a) mean symptoms (i.e. pain, fever) scores; (b) number of analgesic tables used; (c) contralateral otitis; (d) spontaneous perforation of tympanic membrane; (e) mean number of days of otorrhoea; (f) tympanometry results at 1 week, 4 weeks and 3 months Initial visits were performed at home: otoscopy and bacterial culture from nasopharynx were performed Score cards were given to parents Follow‐up visits at hospital at day 2 to 3, day 7, week 4 and week 12. If supplementary treatment was required at day 2 to 3, then myringotomy was performed. If supplementary treatment was required at day 7, then amoxicillin was given | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation performed by pharmaceutical company. Penicillin and placebo were supplied in coded bottles to study personnel |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Identical taste and appearance to amoxicillin and placebo not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Patients not included in analysis ‐ N = 9 (6%). Reasons described, unclear from which treatment group patients were excluded |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, Internet‐based random number generator Concealment of allocation ‐ unclear; method not described Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ reasons described, unclear from which treatment group patients were excluded Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 186 children (N = 179 patients were included in analysis; 7 patients were excluded due to non‐compliance with protocol) Age ‐ between 2 and 16 years Setting ‐ general practice: 32 healthcare centres and 72 general practitioners in Sweden Inclusion criteria ‐ acute otitis media (AOM) was based on direct inspection of the eardrum by pneumatic otoscope or preferably an aural microscope. Findings had to include a bulging, red eardrum displaying reduced mobility Exclusion criteria ‐ perforation of the eardrum, chronic ear conditions or impaired hearing, previous adverse reactions to penicillin, concurrent disease that should be treated with antibiotics, recurrent AOM (3 or more AOM episodes during the past 6 months), children with immunosuppressive conditions, genetic disorders and mental disease or retardation Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ immediate treatment with antibiotics: phenoxymethylpenicillin 25 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days; N = 92 The guardians received written information about how to act if the condition did not improve or got worse within 3 days after randomisation | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes ‐ (a) pain at day 0, 1, 2 and 3 to 7; (b) use of analgesics at day 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 to 7; (c) fever > 38 °C at day 0, 1, 2 and 3 to 7; (d) subjective recovery at day 14 and 3 months; (e) perforations at 3 months; (f) serous otitis media at 3 months All participants were asked to complete a symptom diary for 7 days; a nurse telephoned all participants after approximately 14 days to supplement the information in the diary and to register all acute contacts that had occurred during the first week of treatment; the final follow‐up was performed after 3 months to register perforations and serous otitis media | |

| Notes | Open‐label trial comparing immediate antibiotic prescribing versus expectant observation (no prescription provided but advice on what to do if symptoms did not improve or worsened) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Internet‐based random number generator |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method not described |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Open‐label trial, outcome assessment not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Patients not included in analysis ‐ N = 7 (4%). Reasons described, unclear from which treatment group patients were excluded |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, computer‐assisted randomisation Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 283 children (N = 265 children included in analysis at days 4 to 6) Age ‐ between 6 months and 12 years Setting ‐ secondary care: paediatric emergency department of Yale‐New Haven Hospital in New Haven (USA) Inclusion criteria ‐ the diagnosis of acute otitis media (AOM) was made at the discretion of the clinician according to the diagnostic criteria in the evidence‐based guideline published in Pediatrics 2004 Exclusion criteria ‐ presence of additional intercurrent bacterial infection such as pneumonia, if the patient appeared to be "toxic" as determined by the clinician, hospitalisation, immunocompromised children, antibiotic treatment < 1 week prior to randomisation, children who had either myringotomy or a perforated tympanic membrane, uncertain access to medical care (e.g. no telephone access), primary language of parents was neither English nor Spanish, previous enrolment in the study Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ immediate treatment with antibiotics; N = 145 (N = 133 included in analysis at days 4 to 6) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ proportion of each group that filled the prescription for an antibiotic. This was defined by whether the parent filled the prescription within 3 days of enrolment and was determined by the response to this question at the interview at day 4 to 6 Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) clinical course of the illness; (b) adverse effects of medications; (c) days of school or work missed; (d) unscheduled medical visits; (e) comfort of parents with management of AOM without antibiotics for future episodes 2 trained research assistants blinded to group assignment conducted standardised, structured telephone interviews with the parents at day 4 to 6, day 11 to 14, day 30 and day 40 after enrolment | |

| Notes | Investigator‐blinded study comparing immediate versus delayed antibiotic prescribing (prescription provided and advised to fill only if symptoms worsen or do not improve) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐assisted randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed, opaque envelopes |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Investigator‐blinded study, parents not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up at day 4 to 6 treatment: N = 12 (8%) and expectant observation: N = 6 (4%) |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, block randomisation, computerised randomisation list Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 84 children (N = 84 children included in analysis at 8 weeks) Age ‐ between 6 months and 15 years Setting ‐ primary and secondary care: children in day care centres attending an AOM prevention trial at the Department of Pediatrics, Oulu University Hospital and children visiting the City of Oulu Health Care Center and Mehiläinen Pediatric Private Practice, Oulu (Finland) Inclusion criteria ‐ acute symptoms of respiratory infection and/or ear‐related symptoms and signs of tympanic membrane inflammation together with middle‐ear effusion at pneumatic otoscopy performed by a study physician Exclusion criteria ‐ ventilation tubes (grommets), AOM complication, amoxicillin allergy, Down syndrome, congenital craniofacial abnormality and immunodeficiency Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ amoxicillin‐clavulanate for 7 days (amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/day divided into 2 daily doses); N = 42 (N = 42 included in analysis) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ time middle‐ear effusion disappearance defined as a normal tympanogram finding (A curve) from both ears on 2 consecutive measurement days (either at home or at the study clinic) Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) time to improved tympanogram findings (i.e. A or C curve) from both ears; (b) time to normal pneumatic otoscopy or otomicroscopy findings from both ears; (c) proportions of children with persistent middle‐ear effusion on days 7, 14 and 60; (d) disappearance of pain; (e) disappearance of fever; (f) use of pain medication; (g) possible adverse effects of antimicrobial treatment Children were examined by the study physician with pneumatic otoscopy or otomicroscopy and tympanometry at study entry, after 3 and 7 days, and then weekly until both ears were healthy according to pneumatic otoscopy or otomicroscopy Families were trained to perform tympanometry using a handheld tympanometer for daily follow‐up at home | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Block randomisation, computerised randomisation list |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation list was kept in the pharmacy, which delivered the study drugs to the families according to the consecutive study number |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Bottles containing amoxicillin‐clavulanate or placebo were indistinguishable, dosing was similar in both groups and placebo mixture was flavoured and sweetened to resemble the taste of amoxicillin‐clavulanate |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All children were included in the analysis |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, block randomisation, method of random sequence generation not described Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 293 children (N = 293 children included in analysis) Age ‐ between 2 and 15 years Setting ‐ secondary care: department of otorhinolaryngology in Halmstad (Sweden) Inclusion criteria ‐ purulent acute otitis media (AOM) (no further criteria described) Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment or AOM episode < 4 weeks prior to randomisation, suspected penicillin allergy, presence of ventilation tubes, sensorineural hearing loss, existence of concomitant infection for which antibiotic treatment was required and chronic diseases Baseline characteristics ‐ not described | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ phenoxymethyl penicillin 50 mg/kg/day twice daily for 7 days; N = 159 (N = 159 included in analysis) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ treatment failure (defined as remaining non‐negligible symptoms such as pain and fever, insufficient resolution of infectious signs during treatment period of 7 days, or both Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) resolution of symptoms over time; (b) AOM relapses; (c) tympanometry, audiometry, or both, results at 4 weeks The children were examined at day 0, days 3 to 4, days 8 to 10 and at 4 weeks Parents were instructed to record symptoms (i.e. temperature, otalgia, discharge from ear and consumption of supplied symptomatic drugs) | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Block randomisation, method of random sequence generation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation list was kept by the clinical pharmacologist of the hospital and not disclosed to the investigators until the clinical trial was completed |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear; baseline characteristics ‐ not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Placebo with same taste and appearance as penicillin |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No children lost to follow‐up for primary analysis |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, computerised random number generator with block length of 10 Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ yes Loss to follow‐up ‐ described Design ‐ parallel | |

| Participants | N ‐ 322 children (N = 319 children were included in analysis) Setting ‐ general practice: healthcare centre of Turku (Finland) Inclusion criteria ‐ acute otitis media (AOM) based on 3 criteria: (a) middle‐ear fluid had to be detected by means of pneumatic otoscopic examination that showed at least 2 of the following tympanic membrane findings: bulging position, decreased or absent mobility, abnormal colour or opacity not due to scarring, or air fluid interfaces; (b) at least 1 of the following acute inflammatory signs in the tympanic membrane had to be present: distinct erythematous patches or streaks or increased vascularity over full, bulging, or yellow tympanic membrane; (c) presence of acute symptoms such as fever, otalgia or respiratory symptoms Exclusion criteria ‐ ongoing antibiotic treatment; AOM with spontaneous perforation of the tympanic membrane; systemic or nasal steroid therapy within 3 preceding days; antihistamine, oseltamivir or a combination therapy within 3 preceding days; contraindication to penicillin or amoxicillin; presence of ventilation tube; severe infection requiring antibiotic treatment; documented Epstein‐Barr virus infection within 7 preceding days; Down's syndrome or other condition affecting middle‐ear diseases; known immunodeficiency Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ amoxicillin‐clavulanate 40‐5.7 mg/kg daily in 2 doses for 7 days; N = 162 (N = 161 included in analysis) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ time to treatment failure (i.e. a composite endpoint consisting of 6 independent components: (a) no improvement in overall condition at day 2, (b) worsening of the child's overall condition at any time, (c) no improvement in otoscopic signs at day 7, (d) perforation of tympanic membrane at any time, (e) severe infection (e.g. mastoiditis or pneumonia) necessitating systemic open‐label antimicrobial treatment at any time, (f) any other reason for stopping the study drug at any time Secondary outcomes ‐ assessed by study physician ‐ (a) time to the initiation of rescue treatment; (b) time to development of contralateral AOM; ‐ diary symptom assessment; (c) resolution of symptoms; (d) use of analgesics Parents were given a diary to record symptoms, doses of study drugs and any other medications and adverse events First visit after enrolment (= day 0) was scheduled at day 2. End‐of‐treatment visit was scheduled at day 7 | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerised random number generator with block length of 10 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Concealment of allocation by the pharmacist (independent to trial team) by labelling the identical opaque study drug containers with allocation numbers; allocation list was kept at the paediatric infectious disease ward behind locked doors |

| Other bias | Low risk | ITT analysis ‐ yes, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Placebo with same taste and appearance as amoxicillin‐clavulanate |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up ‐ treatment: N = 1 (1%) and placebo: N = 2 (1%) |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, method of randomisation not described Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ reasons not described, unclear from which treatment group patients were excluded Design ‐ 2 x 2 factorial design | |

| Participants | N ‐ 202 children (N = 171 children included in analysis; N = 31 were excluded from the study) Age ‐ between 2 and 12 years Setting ‐ both general practice and secondary care: 12 general practitioners in or near Tilburg (the Netherlands) recruited patients and referred them to 1 of the 3 otorhinolaryngologists, which excluded those cases where there was disagreement with the diagnosis Inclusion criteria ‐ acute otitis media (AOM) was based on history and clinical picture (i.e. diffuse redness, bulging of the eardrum, or both) Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment < 2 weeks prior to randomisation, chronic otitis or otitis media serosa, contraindication for antibiotic treatment Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ sham myringotomy and amoxicillin 250 mg 3 times daily for 7 days; N = 47 | |

| Outcomes | Main outcomes ‐ (a) parent report of pain at day 0, 1 and 7; (b) otoscopic findings at day 0, 1 and 7; (c) discharge from ear at day 1, 7 and 14; (d) mean temperature at day 0, 1 and 7; (e) AOM relapses at 6 months; (f) audiogram findings after 4 and 8 weeks | |

| Notes | van Buchem 1981a is the 2 arms without myringotomy | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation performed by otorhinolaryngologists; general practitioner and parent/child were outcome assessors and remained blinded |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Sham myringotomy and placebo was similar with amoxicillin with regard to appearance and taste |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up/exclusions ‐ N = 31 (15%). Reasons not described |

| Methods | Randomised ‐ yes, method of randomisation not described Concealment of allocation ‐ adequate Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) ‐ unclear Loss to follow‐up ‐ reasons not described, unclear from which treatment group patients were excluded Design ‐ 2 x 2 factorial design | |

| Participants | N ‐ 202 children (N = 171 children included in analysis; N = 31 were excluded from the study) Age ‐ between 2 and 12 years Setting ‐ both general practice and secondary care: 12 general practitioners in or near Tilburg (the Netherlands) recruited patients and referred them to 1 of the 3 otorhinolaryngologists who excluded those cases where there was disagreement with the diagnosis Inclusion criteria ‐ acute otitis media (AOM) was based on history and clinical picture (i.e. diffuse redness, bulging of the eardrum, or both) Exclusion criteria ‐ antibiotic treatment < 2 weeks prior to randomisation, chronic otitis or otitis media serosa, contraindication for antibiotic treatment Baseline characteristics ‐ balanced | |

| Interventions | Tx ‐ myringotomy and amoxicillin 250 mg 3 times daily for 7 days; N = 48 | |

| Outcomes | Main outcomes ‐ (a) parent report of pain at day 0, 1 and 7; (b) otoscopic findings at day 0, 1 and 7; (c) discharge from ear at day 1, 7 and 14; (d) mean temperature at day 0, 1 and 7; (e) AOM relapses at 6 months; (f) audiogram findings after 4 and 8 weeks | |

| Notes | van Buchem 1981b is the 2 arms with myringotomy | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of randomisation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation performed by otorhinolaryngologists; general practitioner and parent/child were outcome assessors and remained blinded |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | ITT analysis ‐ unclear, baseline characteristics ‐ balanced |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Sham myringotomy and placebo was similar with amoxicillin with regard to appearance and taste |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up/exclusions ‐ N = 31 (15%). Reasons not described |

AOM: acute otitis media

AOM‐SOS: otitis media ‐ severity of symptoms

C: control

ITT: intention‐to‐treat

Tx: treatment

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| No comparison of antibiotic to placebo or expectant observation: trial comparing single‐dose, extended‐release azithromycin versus a 10‐day regimen of amoxicillin/clavulanate | |

| No comparison of antibiotic to placebo or expectant observation: trial comparing high‐dose amoxicillin/clavulanate versus cefdinir | |

| Short versus long course of therapy | |

| No comparison of antibiotic to placebo; the 3 arms were Augmentin, myringotomy, or both | |

| No comparison of antibiotic to placebo or expectant observation: trial comparing single oral doses azithromycin in extended‐release versus immediate‐release formulations | |

| Non‐randomised study | |

| Non‐randomised study: assigned "randomly" based on case number but then allowed to change groups | |

| Conducted in children with ventilation tubes | |

| No comparison of antibiotic to placebo. Method of randomisation not provided and groups appear to be unbalanced at baseline | |

| Secondary analysis of placebo‐controlled trial. This study included the total group of children allocated to immediate antimicrobial treatment (N = 161) and a subgroup of children from the placebo group that received delayed antibiotics (N = 53). As a consequence, comparability of prognosis achieved through randomisation is violated, producing groups of children that are incomparable, which may lead to biased effect estimates | |

| Non‐randomised study |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Antibiotics for asymptomatic acute otitis media |

| Methods | Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled randomised clinical trial |

| Participants | Aboriginal children aged between 6 and 30 months diagnosed with asymptomatic acute otitis media defined as a bulging tympanic membrane without associated symptoms (including ear pain, fever or ear discharge) at the time of diagnosis |

| Interventions | Azithromycin 30 mg/kg divided into 2 doses or placebo for 7 days |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome ‐ proportion of children with a bulging tympanic membrane or ear discharge or withdrawn due to complications or side effects at 14 days (all children who are lost to follow‐up are considered clinical failures) Secondary outcomes ‐ (a) proportion of children with unresolved bulging at 7 and 30 days; (b) proportion of children with a bulging tympanic membrane or ear discharge or withdrawn due to complications or side effects at 7, 14 and 30 days (not including children who are lost to follow‐up); (c) proportion of children who develop an illness requiring additional medical treatment at 7, 14 and 30 days; (d) proportion of children who develop an illness requiring cessation of prescribed antibiotics at 30 days; (e) proportion of children who have no improvement in other conditions recorded, like skin sores and rhinosinusitis, at 7, 14 and 30 days; (f) microbiological outcomes including carriage and antibiotic resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae at 7, 14 and 30 days |

| Starting date | March 2007 |

| Contact information | Menzies School of Health Research, PO Box 41096, Casuarina NT 0811, Australia |

| Notes | ACTRN12608000424303 |

Data and analyses

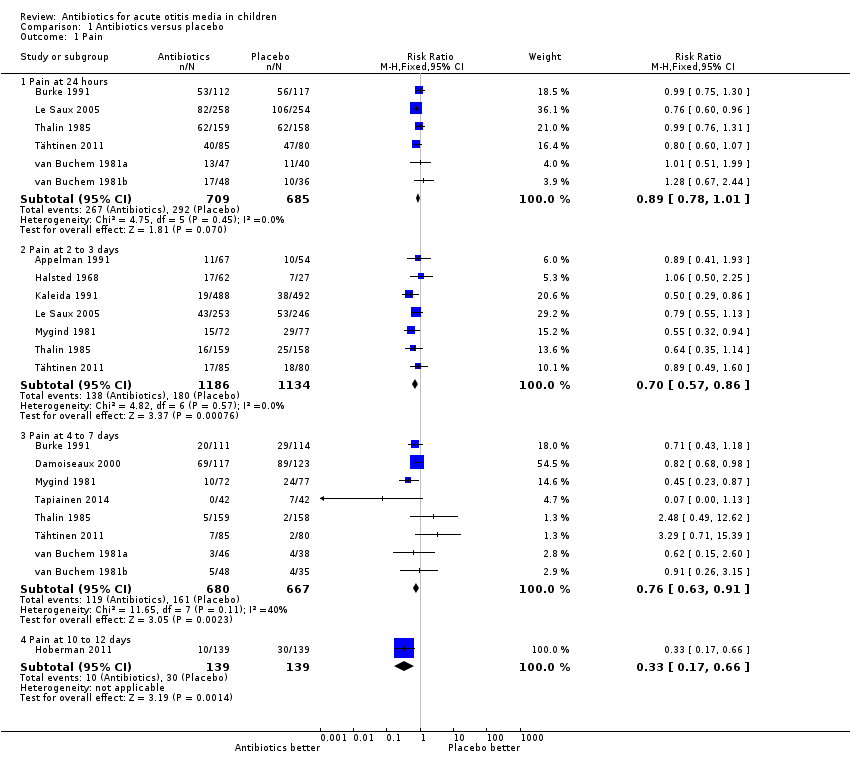

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

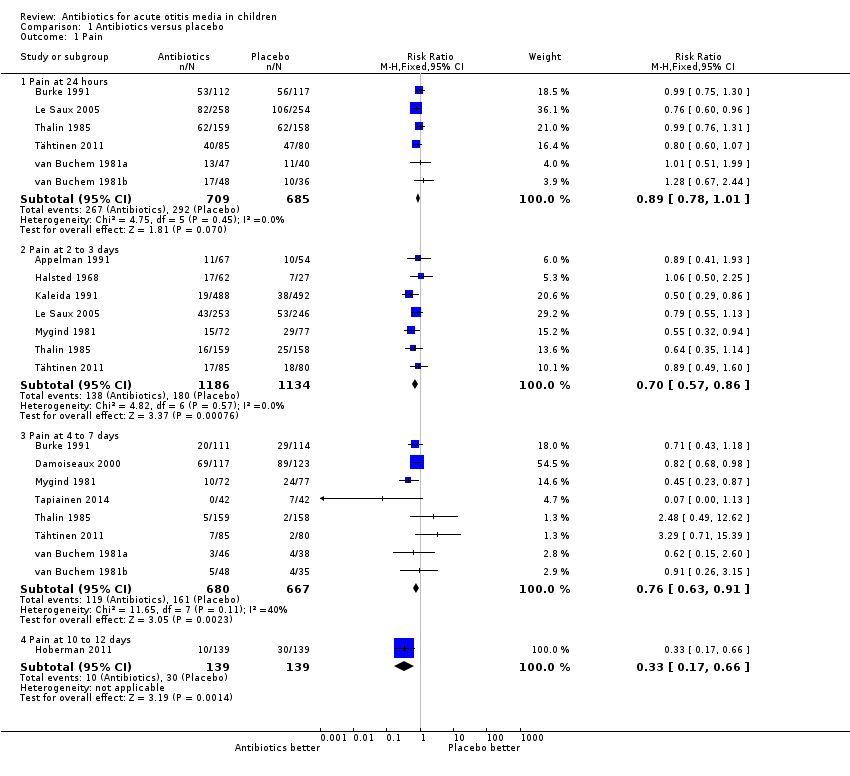

| 1 Pain Show forest plot | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pain. | ||||

| 1.1 Pain at 24 hours | 6 | 1394 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.78, 1.01] |

| 1.2 Pain at 2 to 3 days | 7 | 2320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.57, 0.86] |

| 1.3 Pain at 4 to 7 days | 8 | 1347 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.63, 0.91] |

| 1.4 Pain at 10 to 12 days | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.17, 0.66] |

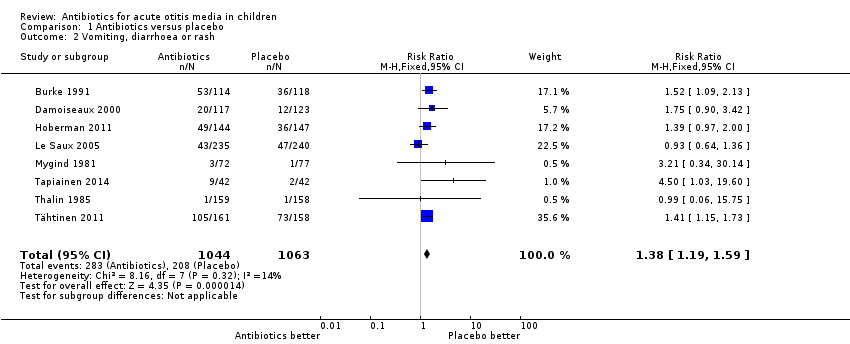

| 2 Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash Show forest plot | 8 | 2107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [1.19, 1.59] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 2 Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash. | ||||

| 3 Abnormal tympanometry Show forest plot | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 3 Abnormal tympanometry. | ||||

| 3.1 2 to 4 weeks | 7 | 2138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.74, 0.90] |

| 3.2 6 to 8 weeks | 3 | 953 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.78, 1.00] |

| 3.3 3 months | 3 | 809 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.24] |

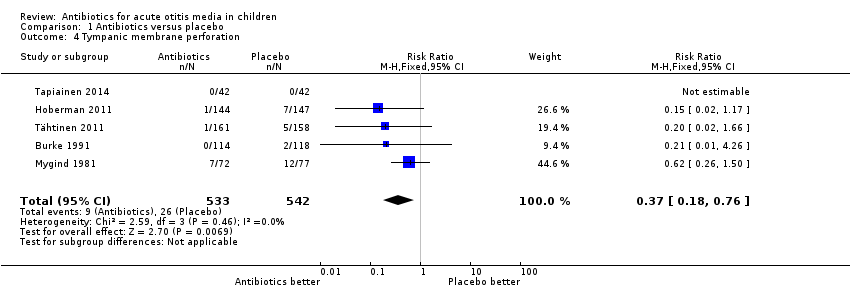

| 4 Tympanic membrane perforation Show forest plot | 5 | 1075 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.18, 0.76] |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 4 Tympanic membrane perforation. | ||||

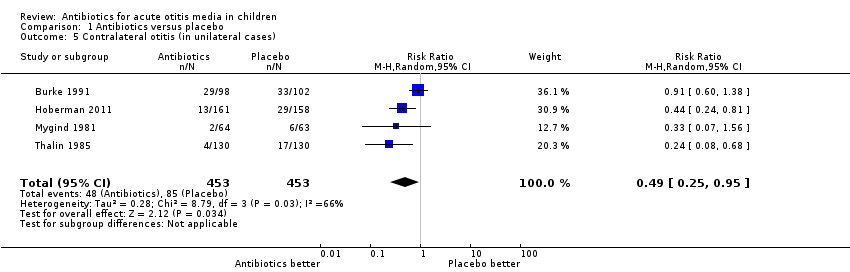

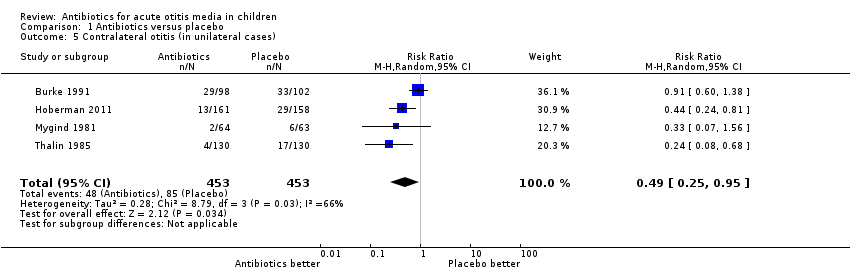

| 5 Contralateral otitis (in unilateral cases) Show forest plot | 4 | 906 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.25, 0.95] |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 5 Contralateral otitis (in unilateral cases). | ||||

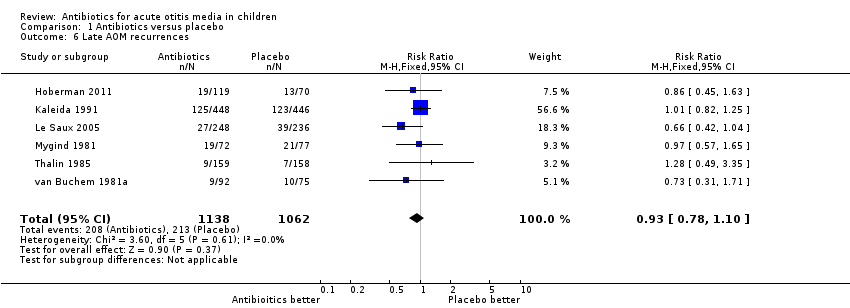

| 6 Late AOM recurrences Show forest plot | 6 | 2200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.78, 1.10] |

| Analysis 1.6  Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 6 Late AOM recurrences. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

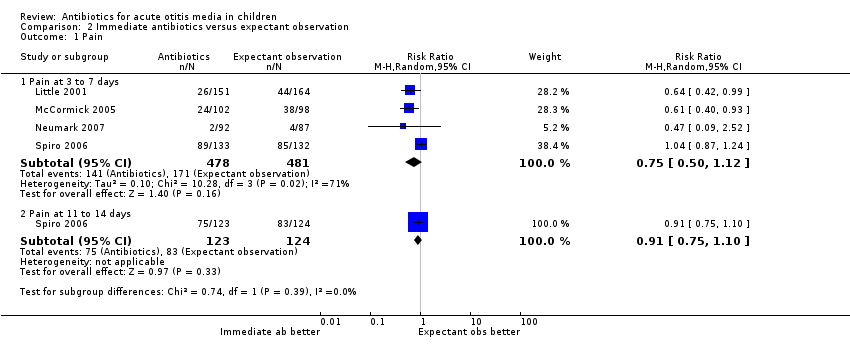

| 1 Pain Show forest plot | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 1 Pain. | ||||

| 1.1 Pain at 3 to 7 days | 4 | 959 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.50, 1.12] |

| 1.2 Pain at 11 to 14 days | 1 | 247 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.75, 1.10] |

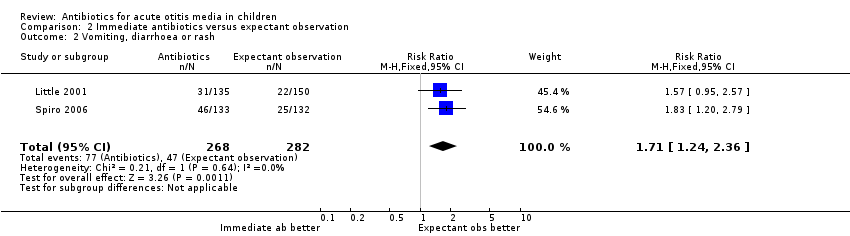

| 2 Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash Show forest plot | 2 | 550 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [1.24, 2.36] |

| Analysis 2.2  Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 2 Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash. | ||||

| 3 Abnormal tympanometry at 4 weeks Show forest plot | 1 | 207 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.78, 1.35] |

| Analysis 2.3  Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 3 Abnormal tympanometry at 4 weeks. | ||||

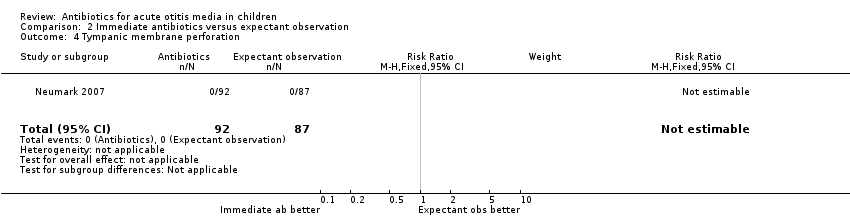

| 4 Tympanic membrane perforation Show forest plot | 1 | 179 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| Analysis 2.4  Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 4 Tympanic membrane perforation. | ||||

| 5 AOM recurrences Show forest plot | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.74, 2.69] |

| Analysis 2.5  Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 5 AOM recurrences. | ||||

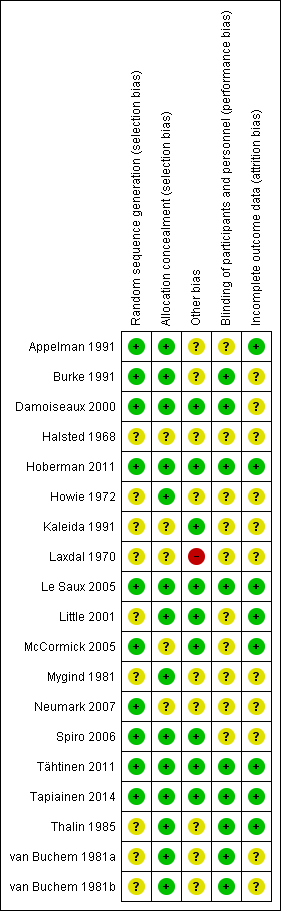

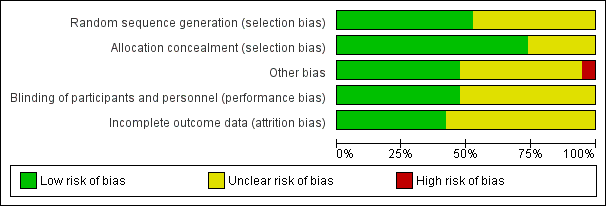

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

L'Abbé plot of the rates of pain at 24 hours for the placebo (control) versus antibiotic (experimental) group.

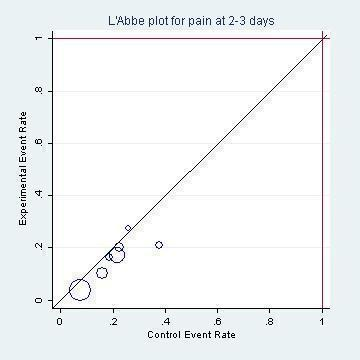

L'Abbé plot of the rates of pain at two to three days for the placebo (control) versus antibiotic (experimental) group.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotic versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Pain.

Percentage with pain based on the subset of six studies included in the IPD meta‐analysis (Rovers 2006).

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pain.

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 2 Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash.

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 3 Abnormal tympanometry.

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 4 Tympanic membrane perforation.

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 5 Contralateral otitis (in unilateral cases).

Comparison 1 Antibiotics versus placebo, Outcome 6 Late AOM recurrences.

Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 1 Pain.

Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 2 Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash.

Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 3 Abnormal tympanometry at 4 weeks.

Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 4 Tympanic membrane perforation.

Comparison 2 Immediate antibiotics versus expectant observation, Outcome 5 AOM recurrences.

| Antibiotics versus placebo for acute otitis media in children | ||||||

| Patient or population: children with acute otitis media | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | No of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Antibiotics versus placebo | |||||

| Pain ‐ pain at 24 hours | Study population | RR 0.89 | 1394 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | ||

| 426 per 1000 | 379 per 1000 | |||||

| Pain ‐ pain at 2 to 3 days | Study population | RR 0.70 | 2320 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | ||

| 159 per 1000 | 111 per 1000 | |||||

| Pain ‐ pain at 4 to 7 days | Study population | RR 0.76 | 1347 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | ||

| 241 per 1000 | 183 per 1000 | |||||

| Pain ‐ pain at 10 to 12 days | Study population | RR 0.33 | 278 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | ||

| 216 per 1000 | 71 per 1000 | |||||

| Abnormal tympanometry ‐ 2 to 4 weeks | Study population | RR 0.82 | 2138 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | ||

| 481 per 1000 | 395 per 1000 | |||||

| Abnormal tympanometry ‐ 3 months | Study population | RR 0.97 | 809 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | ||

| 241 per 1000 | 234 per 1000 | |||||

| Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash | Study population | RR 1.38 | 2107 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | ||

| 196 per 1000 | 270 per 1000 | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk for ‘Study population’ was the average risk in the control groups (i.e. total number of participants with events divided by total number of participants included in the meta‐analysis). The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1The number of studies reported in the 'Summary of findings' table for the outcomes 'Pain at 24 hours' and 'Pain at 4 to 7 days' differ slightly from those reported in the Data Analysis Table 1 ‐ Antibiotics versus placebo (five versus six studies and seven versus eight studies, respectively). This is due to the van Buchem trial. This trial is included as one study in our review (and in the 'Summary of findings' table), but we included data from two different comparisons from this 2 x 2 factorial design trial in our analyses (van Buchem 1981a; van Buchem 1981b). 2We downgraded the evidence for pain at days 10 to 12 from high quality as this outcome was not specified a priori in this trial (secondary analysis). | ||||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Pain Show forest plot | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Pain at 24 hours | 6 | 1394 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.78, 1.01] |

| 1.2 Pain at 2 to 3 days | 7 | 2320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.57, 0.86] |

| 1.3 Pain at 4 to 7 days | 8 | 1347 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.63, 0.91] |

| 1.4 Pain at 10 to 12 days | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.17, 0.66] |

| 2 Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash Show forest plot | 8 | 2107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [1.19, 1.59] |

| 3 Abnormal tympanometry Show forest plot | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 2 to 4 weeks | 7 | 2138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.74, 0.90] |

| 3.2 6 to 8 weeks | 3 | 953 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.78, 1.00] |

| 3.3 3 months | 3 | 809 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.24] |

| 4 Tympanic membrane perforation Show forest plot | 5 | 1075 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.18, 0.76] |

| 5 Contralateral otitis (in unilateral cases) Show forest plot | 4 | 906 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.25, 0.95] |

| 6 Late AOM recurrences Show forest plot | 6 | 2200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.78, 1.10] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Pain Show forest plot | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Pain at 3 to 7 days | 4 | 959 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.50, 1.12] |

| 1.2 Pain at 11 to 14 days | 1 | 247 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.75, 1.10] |

| 2 Vomiting, diarrhoea or rash Show forest plot | 2 | 550 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [1.24, 2.36] |

| 3 Abnormal tympanometry at 4 weeks Show forest plot | 1 | 207 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.78, 1.35] |

| 4 Tympanic membrane perforation Show forest plot | 1 | 179 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 AOM recurrences Show forest plot | 1 | 209 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.74, 2.69] |