Pharmacological interventions for drug‐using offenders

References

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to studies awaiting assessment

Additional references

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Methods | Allocation:random assignment | |

| Participants | 120 male participants 100% male Age range: 20‐70 years Mean age: 35.7 years (SD 8.86) Participants had to have a history of opioid use for longer than one year, had to be dependent upon drugs and had to have a sentence length greater than 6 months. In addition, non-death penalty inmates were excluded, and individuals had to be willing to engage in services | |

| Interventions | The intervention group received methadone treatment in combination with CBT and widely focused on coping and problem‐solving skills. The comparison group received non‐methadone drugs plus standard psychiatric services and therapeutic medications. | |

| Outcomes | Drug use: yes/no Frequency of drug injections (percentage) Syringe sharing Morphine urine analysis All outcomes at six months | |

| Notes | After random allocation, 20 participants who were allocated to the control group opted out of the research. This group of inmates were subsequently replaced by individuals from the general inmate population | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Participants were categorised into one of four lists based on their previous history of drug abuse. The random allocation was then chosen, using even and odd row numbers from each list |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | After random allocation, 20 participants from the control group opted out of the research |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not clearly reported but problems with the research design are highlighted |

| Other bias | High risk | The authors note a number of operational difficulties, especially in relation to contamination across prison wings and the two intervention groups |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment | |

| Participants | 51 adults Average age: 39 years 90% male 24% white 62% African American 14% Latino | |

| Interventions | Community‐based naltrexone programme and routine parole/probation vs routine parole/probation | |

| Outcomes | Incarceration for technical violation (official records) during the past 6 months at 6 months' follow‐up | |

| Notes | Work supported by NIDA Grant DA05186. No declarations of interest are noted by the authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Individuals were assigned at a ratio of 2:1 to naltrexone vs control |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | study description suggests that participants were not blind. see p.531 |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | study description suggests that participants were not blind. see p.531 |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Blinding of urine samples were not shared with probation staff. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All allocated participants were reported in the analysis. Retention rates appeared to be similar; appears to be an ITT analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups similar at baseline, but potential for volunteer bias |

| Methods | Allocation: random Randomisation method: unknown/unclear Similar on drug use: significant difference in heroin use. Otherwise similar Similar on criminal activity: yes Blinding methodology: high risk Loss to follow‐up: inadequate/high risk | |

| Participants | 111 adults Age range: 18‐55 years; average age: 34 years 82% male 47% Caucasian 100% drug users Alcohol use not reported but participants excluded if severe alcohol dependence Psychiatric history not reported Eligibility criteria: consented, age 18‐55 years, opioid dependence, otherwise good health, probation or parole for 6 months, 3 days opioid free | |

| Interventions | Community pharmacological intervention vs treatment as usual (I) Oral naltrexone plus psychosocial treatment (n = 56) vs (C) psychosocial treatment only The (I) group was started on directly observed administration of naltrexone, increasing in dose from 25 mg to 300 mg and was also given psychosocial treatment. The (C) group was given a treatment regimen consisting of group therapy, individual therapy and case management, all of which the (I) group also received | |

| Outcomes | Criminal activity (self‐reported) and criminal record data at 6 months Illicit drug use (self‐reported) during the 30 days before the interview at 6 months % positive urine drug screen for opioids % positive urine drug screen for cocaine | |

| Notes | The study was supported by grant R01‐DA‐012268 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD (Dr. Cornish). Declaration of Interest In the past 3 years, Dr. O’Brien has served as a consultant on one occasion to Alkermes, a company that makes a version of depot naltrexone. He is also conducting an NIH funded study of this medication in opioid addiction.The authors report no conflicts of interest. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation method unclear. Note that randomisation was balanced by using six variables |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | page 4 'we did not use a placebo for participants'. The treatment as usual group were not blinded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | page 4 'we did not use a placebo for participants'. The treatment as usual group were not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | A large amount of attrition was noted in the first week, and only one‐third of participants remained at 6‐month follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Other bias | High risk | Blinding and attrition concerns throughout the study |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment, random number table-first 9 people put on intervention | |

| Participants | 36 adults Mean age: 31.8 years (SD 8.4) 100% female 89% white 100 drug users Alcohol use: yes-percentage not available 54.3% prescribed medication for mental illness Eligibility criteria: adult women, opioid dependent, interest in treatment for opioid dependence, no contraindications for buprenorphine, due for release from residential treatment within the month, returning to the community, release to correct area | |

| Interventions | Community‐based pharmacological intervention vs placebo (I) buprenorphine (n = 24) vs (C) placebo (n = 12) (I) group was started on 2 mg of buprenorphine, increased to target dose of 8 mg at discharge. Only 37.2% reached target dose at discharge. (Doses were lower than standard induction, as participants had been in a controlled environment for some time without access to opiates.) Doses were titrated up to a maximum of 32 mg per day in the community, as clinically indicated. Participants were assessed weekly for side effects, were given drug testing and were counselled by the study physician if using drugs. The treatment course was 12 weeks. The (C) group was given a placebo on the same regimen as the (I) group | |

| Outcomes | % injection drug use and % urine opiates at end of treatment and at 3 months' follow‐up | |

| Notes | This project was supported by funding from NIDA R21DA019838 The authors have no declarations of interest | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | First 9 participants deliberately allocated to intervention for practical reasons; use of a random number table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Use of sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | This trial began as an open label trial then became a double blind trial of participants and providers on all outcomes. Some concerns about contamination issues with the placebo group but difficult to assess to what extent the blinding might have been affected. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | This trial began as an open label trial then became a double blind trial of participants and providers on all outcomes. Some concerns about contamination issues with the placebo group but difficult to assess to what extent the blinding might have been affected. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no evidence to provide information about whether the assessors were blind |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no evidence to provide information about whether the assessors were blind |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | A total of 8 individuals were not included in the final analysis after randomisation |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other concerns within the methodology |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment | |

| Participants | 382 adults and young offenders | |

| Interventions | Secure establishment‐based pharmacological intervention versus waiting‐list control | |

| Outcomes | Heroin use (hair analysis) and self‐reported heroin use during the past 2 months at 2 months' follow‐up | |

| Notes | Funding was provided by the Commonwealth Department The authors have no declarations of interest | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomisation by phone |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation held by researcher not involved in recruiting or interviewing participants. Trial nurses had no access to lists |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Flow chart (p. 61) indicates that 30% withdrew but unable to tell what impact this would have on findings |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes in objectives were reported in results |

| Other bias | Low risk | Power calculation (p 61) Baseline characteristics largely similar (p 61) Some control participants received Tx, some Tx not given; methadone tested by subgroup analysis |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment | |

| Participants | 32 males Heroin addicts 5 years or longer 5 or more previous convictions 15 European, 10 negro, 7 Puerto Rican With a population of heroin‐dependent prerelease prisoners | |

| Interventions | Methadone vs waiting‐list control. Methadone was prescribed on admission to a hospital unit where individuals were given 10 mg per day, gradually increasing to a dose of 35 mg | |

| Outcomes | Heroin use Re‐incarceration Treatment retention Employment At 7 to 10 months, 50 weeks | |

| Notes | Participants were chosen by a lottery based on release dates between January 1 and April 30 1968. Supported by grants from the Health Research Council and the New York State Narcotics Addiction Control Commission. No declarations of interest by the authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation by lottery, no further details of the study method provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No missing data on key outcomes |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Intent‐to‐treat analysis not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Representativeness of the small sample with no urine analysis in follow‐up of controls |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment | |

| Participants | 126 adult males | |

| Interventions | Prison/secure establishment‐based levo‐alpha‐acetyl methanol + transfer to methadone maintenance after release vs untreated controls | |

| Outcomes | Heroin use during 9‐month follow‐up (self‐report), arrests during 9‐month follow‐up (official records) and re‐incarceration during 9‐month follow‐up (official records), frequency of illegal activity, admission to drug use and average weekly income obtained from illegal activities | |

| Notes | No funding information provided No declaration of interest by the authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported other than stated 'random' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | A considerable number of experimental participants declined medication after initial consent and randomisation to the experimental condition (see pp. 437 and 499). High attrition from the experimental group after random assignment and before treatment initiation required revision of the original two‐group study design for purposes of data analyses |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Table 4, p. 446, indicates only selected outcomes. No ITT conducted |

| Other bias | High risk | Experimental and control groups could not be considered comparable (p. 449); therefore, the number of variables was restricted. Study groups were revised after attrition in treatment group. Groups were considered not to be comparable, and the number of variables assessed was restricted. Urine samples and treatment records available on experimental group only |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment | |

| Participants | 211 adult males | |

| Interventions | Prison/secure establishment‐based counselling only vs counselling + initiation of methadone maintenance prerelease continuing to methadone maintenance after release | |

| Outcomes | Urine test for opioids 1 month post‐release, urine test for cocaine 1 month post‐release, self‐report heroin use 1 month post‐release, self‐report cocaine use 1 month post‐release | |

| Notes | 3 months post‐release, 6 months post‐release, 12 months post‐release. Funding for this study was provided by Grant R01 DA 16237 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). No declarations of interest reported by the authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Block randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Individuals in the counselling only group did not receive treatment |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Contamination of treatment groups |

| Methods | Allocation: random Randomisation method: permuted block protocol Groups similar on drug use at baseline: yes Groups similar on criminal activity at baseline: yes Blinding methodology: not blinded-open label Loss to follow‐up: unknown | |

| Participants | 46 adults Mean age: 35.1 years (SD 7) 93% male Ethnicity: unknown 100% drug users. 86.4% polydrug use Alcohol use: not reported Psychiatric history: not reported Eligibility criteria: inclusion: pre‐incarceration heroin dependence, at least 2 months sentence time remaining. Exclusion: untreated major depression or psychosis, severe hepatic impairment, already in agonist maintenance treatment, pregnant | |

| Interventions | Secure establishment naltrexone intervention vs methadone treatment (I) Received 20‐pellet naltrexone implants around one month before release. Implants give sustained‐release naltrexone over 5 to 6 months (n = 23) vs (C) Initiated on 30 mg methadone per day at around one month pre‐release. Increased over typical period of three weeks to recommended dose of 80 to 130 mg (n = 21) | |

| Outcomes | Mean days per month of criminal activity (self‐reported) at 6 months No. of days in prison (from official records of Norwegian prison) at 6 months Mean days per month using heroin, benzodiazepines and amphetamines (self‐reported) at 6 months | |

| Notes | Funding was provided by the Research Council of Norway No declarations of interest by the authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Treatment allocation sequence performed at an independent centre using a permuted block protocol |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | p143 'the treatment conditions were not blind and may have increased risk if performance bias' |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | p143 'the treatment conditions were not blind and may have increased risk if performance bias' |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Intention‐to‐treat analysis conducted |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No evidence |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other concerns |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment | |

| Participants | 1015 drug‐using offenders | |

| Interventions | Community‐based: diamorphine treatment vs methadone treatment | |

| Outcomes | Drug use and criminal activity (self‐report and official records) | |

| Notes | Article in German, single reviewer translation completed | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Block randomisation used |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Data on all outcomes presented, limited attrition noted |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Methods | Random allocation: to methadone or buprenorphine allocation initially on a 1:1 ratio and subsequently periodically based on 7:3 Randomisation method: inadequate personnel aware of allocation | |

| Participants | 133 male inmates | |

| Interventions | Prison/secure establishment based methadone vs buprenorphine | |

| Outcomes | Arrest (self‐report) during the past 12 months at 3‐month follow‐up, and drug use (self‐report) post‐release at 3‐month follow‐up | |

| Notes | No funding information provided by the authors No declarations of interest reported by the authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random number generator used. Allocation was originally 1:1, but loss in one group meant that treatment‐adaptive randomisation was used at a ratio of 7:3 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Project director was naive to allocation, but research assistant was not |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | no information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Some attrition occurred before medication was received by buprenorphine‐assigned participants. 30% of participants could not be interviewed at follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Participants at one site received methadone sub optimal doses (30 mg). The study contained a modest sample size |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Not original RCT. Data is from previous, older studies. | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| No relevant outcomes reported | |

| Study protocol only | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The intervention was not appropriate for inclusion. | |

| Not offender population | |

| Not RCT | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| 3‐arm study in which only 2 arms were randomised ‐ 1 treatment arm and control arm. Results presented as both treatment arms combined vs control. | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Not offender population | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Paper not available | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Not a drug use intervention | |

| Study population is mothers of offenders, not offenders themselves | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The follow‐up periods reported for the different groups were not equivalent. | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Not offender population | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Not offender population | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| No relevant outcomes reported | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Unclear if study looks at offender population | |

| Some participants were not randomly selected into the treatment groups. | |

| Paper not available and not clear from abstract if looks at offender population | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention. | |

| No relevant outcomes reported | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Participants randomised to receive treatment were not randomised into the different treatment sub‐groups (selected by level of risk). | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Participants not recruited through criminal justice system | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention. | |

| Relevant results from original RCT not reported here | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention. | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention. | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Not offender population | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Not offender population | |

| Not offender population | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| No relevant outcomes reported | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Not offender population | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention | |

| No relevant outcomes reported | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Paper not availbale and not clear from abstract if looks at offenders | |

| Not RCT | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Paper not availbale and not clear from abstract if looks at offenders | |

| Not offender population | |

| The study did not report relevant drug and/or crime outcome measures at both the pre and post intervention periods. | |

| Not RCT | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The population of the study was not 100% drug using offenders that were specifically referred by the criminal justice system to the intervention. | |

| No control group | |

| Not offender population | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| The study did not include an appropriate comparison group. | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Not clear if offender population | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Participants not in criminal justice system | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention | |

| Randomisation broken as 40% of control arm were allowed to receive treatment (acupuncture) outside of the intervention. | |

| Not RCT | |

| Not clear if offender population | |

| Not clear if offender population | |

| Does not concern pharmacological intervention |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment |

| Participants | 61 adults and young offenders |

| Interventions | 6 monthly injections of Depotrex brand naltrexone injections vs extended release |

| Outcomes | 6‐Month outcomes Positive opiate urine tests |

| Notes | Feasibility pilot trial across five sites |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment |

| Participants | 211 adults |

| Interventions | Counselling only in prison vs counselling plus transfer to methadone maintenance treatment upon release vs counselling plus methadone in prison and continued use in the community |

| Outcomes | To be assessed |

| Notes |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment |

| Participants | 618 adults |

| Interventions | Therapuetic community vs less intensive group |

| Outcomes | To be assessed |

| Notes |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment |

| Participants | Adults and young offenders |

| Interventions | Participants with methadone maintenance before release from incarceration vs individuals who were referred to treatment at time of release |

| Outcomes | Heroin use Other opiate use Injection drug use 6‐Month outcomes |

| Notes |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment |

| Participants | 211 adults |

| Interventions | Passive referral to substance abuse treatment upon release vs guaranteed methadone treatment admission upon release vs methadone in prison and guaranteed continuation of methadone upon release |

| Outcomes | 1, 3, 6 months post baseline and 12 months post release |

| Notes |

| Methods | Allocation: random assignment |

| Participants | 306 adults and young offenders |

| Interventions | Daily sublingual buprenorphine or oral methadone and routine care vs standard reduced regimen |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: abstinence from illicit opiates at 8 days using a urine test and self‐report information 8 days post detoxification |

| Notes |

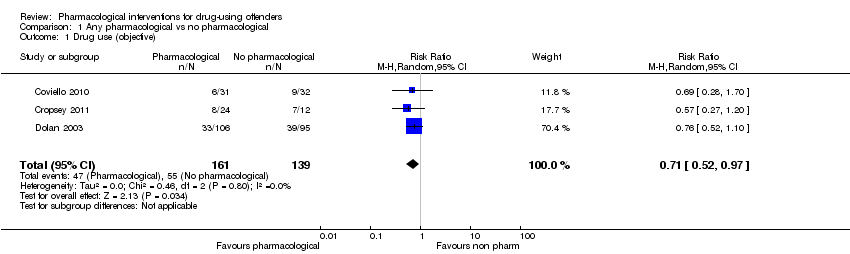

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

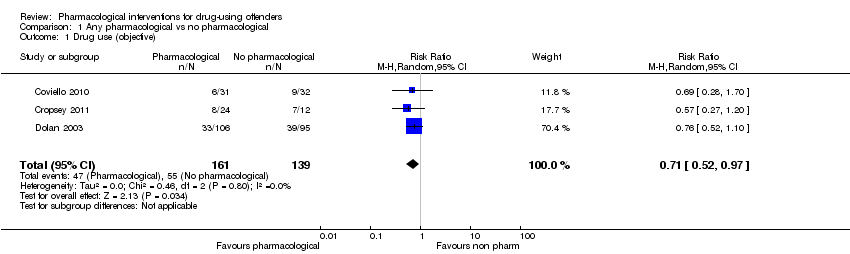

| 1 Drug use (objective) Show forest plot | 3 | 300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.52, 0.97] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Drug use (objective). | ||||

| 2 Drug use community setting Show forest plot | 2 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.35, 1.09] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 2 Drug use community setting. | ||||

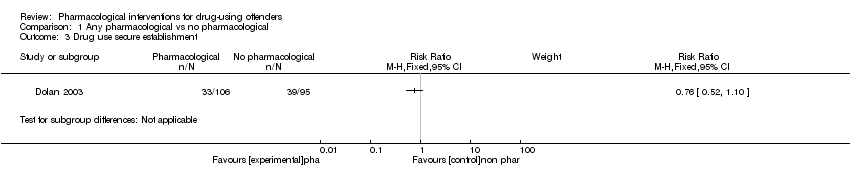

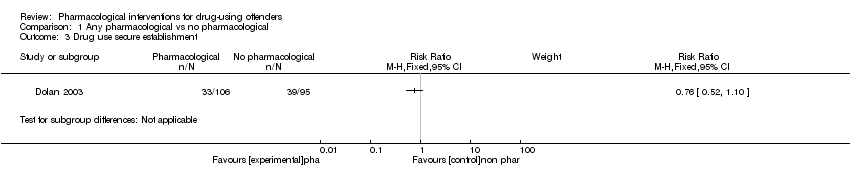

| 3 Drug use secure establishment Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 3 Drug use secure establishment. | ||||

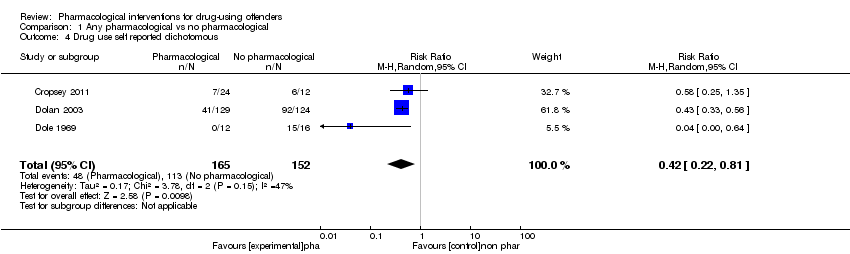

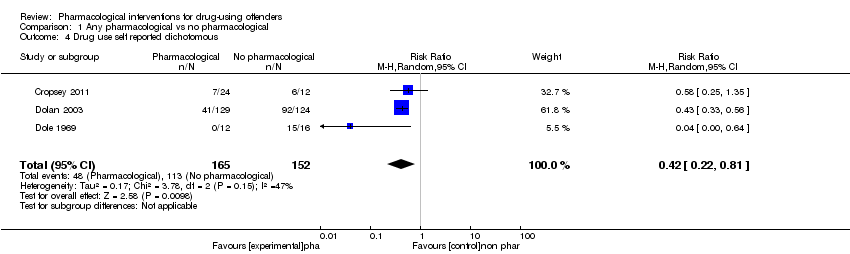

| 4 Drug use self reported dichotomous Show forest plot | 3 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.22, 0.81] |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 4 Drug use self reported dichotomous. | ||||

| 5 Drug use self reported continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 5 Drug use self reported continuous. | ||||

| 6 Criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.6  Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 6 Criminal activity dichotomous. | ||||

| 6.1 Arrests | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.32, 1.14] |

| 6.2 Re‐incarceration | 3 | 142 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.19, 0.56] |

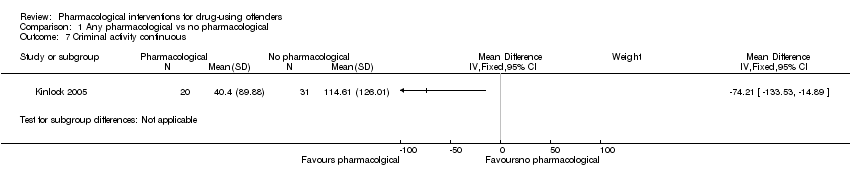

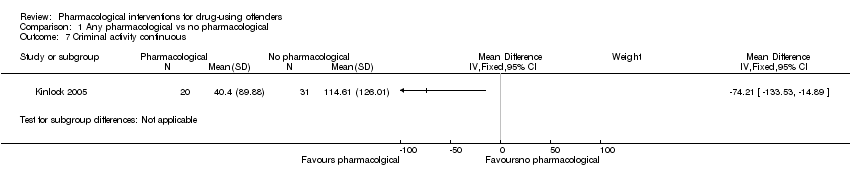

| 7 Criminal activity continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 1.7  Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 7 Criminal activity continuous. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Self report drug use dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Buprenorphine vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Self report drug use dichotomous. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Self‐report drug use dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 3.1  Comparison 3 Methadone vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Self‐report drug use dichotomous. | ||||

| 2 Self report drug use continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 3.2  Comparison 3 Methadone vs no pharmacological, Outcome 2 Self report drug use continuous. | ||||

| 3 Re‐incarceration dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 3.3  Comparison 3 Methadone vs no pharmacological, Outcome 3 Re‐incarceration dichotomous. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

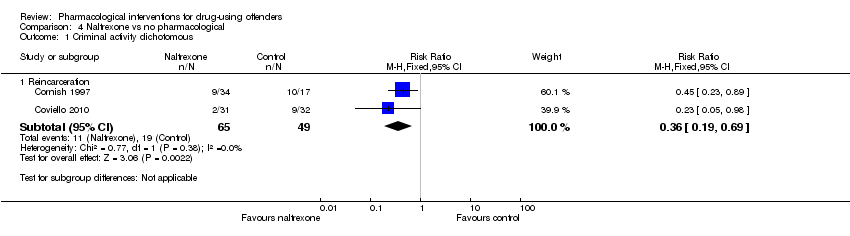

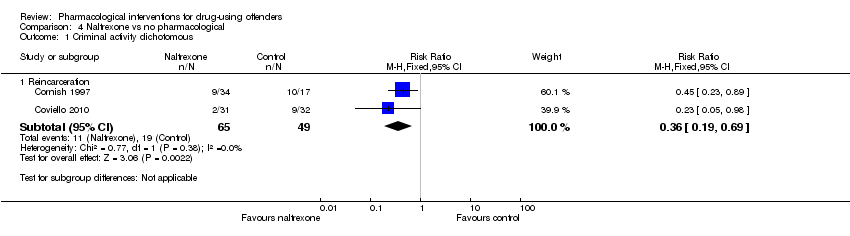

| 1 Criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 4.1  Comparison 4 Naltrexone vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Criminal activity dichotomous. | ||||

| 1.1 Reincarceration | 2 | 114 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.19, 0.69] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

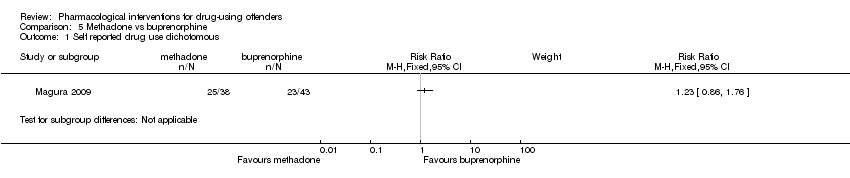

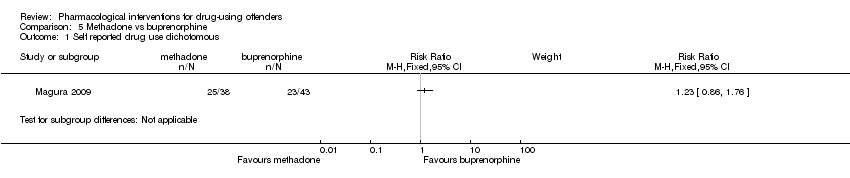

| 1 Self reported drug use dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 5.1  Comparison 5 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 1 Self reported drug use dichotomous. | ||||

| 2 Self reported drug use continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 5.2  Comparison 5 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 2 Self reported drug use continuous. | ||||

| 3 Criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 5.3  Comparison 5 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 3 Criminal activity dichotomous. | ||||

| 3.1 re incarceration | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.83, 1.88] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

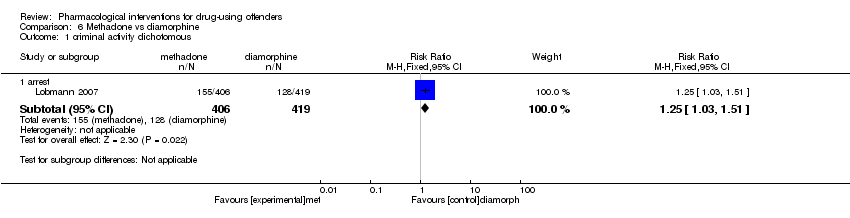

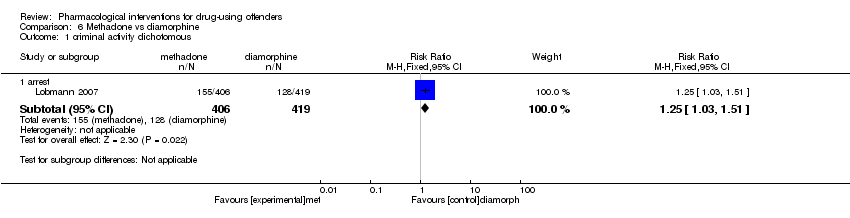

| 1 criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 6.1  Comparison 6 Methadone vs diamorphine, Outcome 1 criminal activity dichotomous. | ||||

| 1.1 arrest | 1 | 825 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.03, 1.51] |

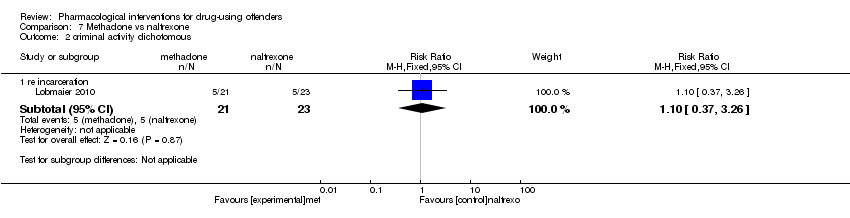

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

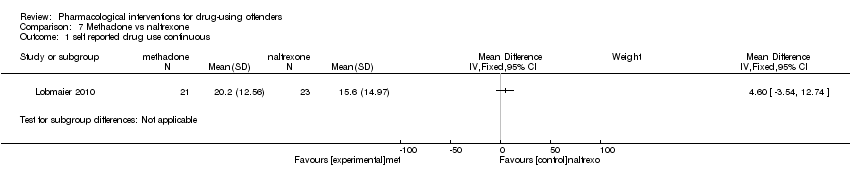

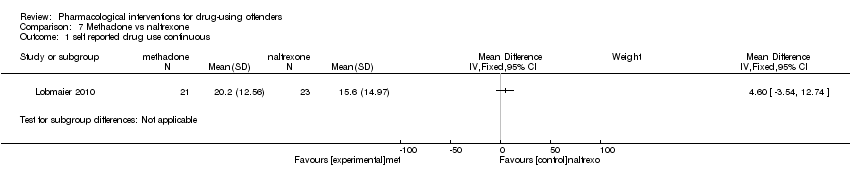

| 1 self reported drug use continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 7.1  Comparison 7 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 1 self reported drug use continuous. | ||||

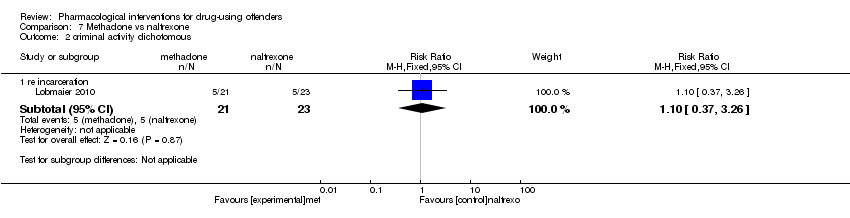

| 2 criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 7.2  Comparison 7 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 2 criminal activity dichotomous. | ||||

| 2.1 re incarceration | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.37, 3.26] |

| 3 criminal activity continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Analysis 7.3  Comparison 7 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 3 criminal activity continuous. | ||||

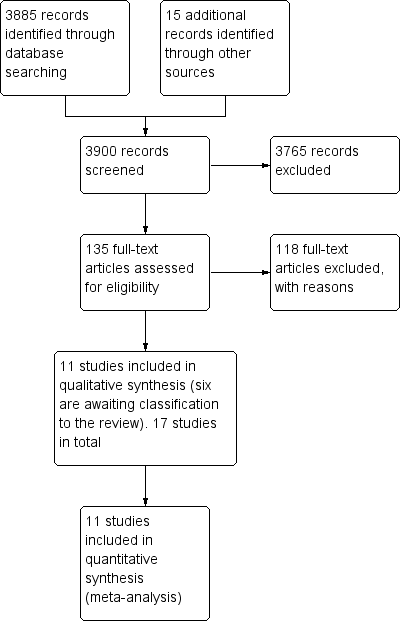

Study flow diagram of papers within the review.

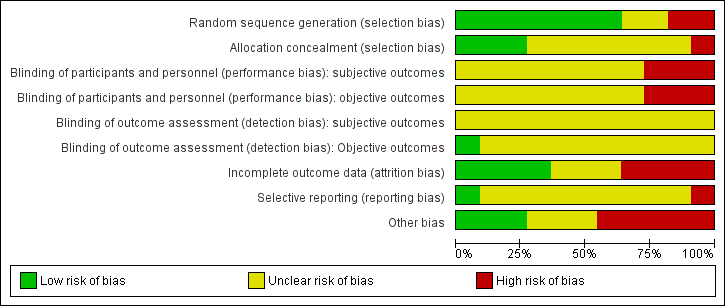

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Drug use (objective).

Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 2 Drug use community setting.

Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 3 Drug use secure establishment.

Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 4 Drug use self reported dichotomous.

Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 5 Drug use self reported continuous.

Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 6 Criminal activity dichotomous.

Comparison 1 Any pharmacological vs no pharmacological, Outcome 7 Criminal activity continuous.

Comparison 2 Buprenorphine vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Self report drug use dichotomous.

Comparison 3 Methadone vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Self‐report drug use dichotomous.

Comparison 3 Methadone vs no pharmacological, Outcome 2 Self report drug use continuous.

Comparison 3 Methadone vs no pharmacological, Outcome 3 Re‐incarceration dichotomous.

Comparison 4 Naltrexone vs no pharmacological, Outcome 1 Criminal activity dichotomous.

Comparison 5 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 1 Self reported drug use dichotomous.

Comparison 5 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 2 Self reported drug use continuous.

Comparison 5 Methadone vs buprenorphine, Outcome 3 Criminal activity dichotomous.

Comparison 6 Methadone vs diamorphine, Outcome 1 criminal activity dichotomous.

Comparison 7 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 1 self reported drug use continuous.

Comparison 7 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 2 criminal activity dichotomous.

Comparison 7 Methadone vs naltrexone, Outcome 3 criminal activity continuous.

| Study | Setting | Intervention | Comparison group | Follow‐up period | Outcome type | Outcome description |

| Prison | Methadone treatment in combination with CBT and widely focused on coping and problem‐solving skills. | Non‐methadone drugs plus standard psychiatric services and therapeutic medications | 6 months | Biological drug use Self‐report drug use | Drug use yes/no Frequency of drug injections (percentage) Syringe sharing Morphine urine analysis | |

| Community | Naltrexone | Routine parole/probation | 6 months and during 6 months of treatment | Criminal activity dichotomous | % re‐incarcerated during 6 months of follow‐up | |

| Community | Naltrexone | Psychosocial treatment only | 6 months | Biological drug use dichotomous Criminal activity dichotomous | % positive urine drug screen opioids % positive urine drug screen cocaine % violating parole/probation | |

| Community | Buprenorphine | Placebo | End of treatment 3 months | Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous | % positive urine opiates % self‐report injection drug use | |

| Prison | Pharmacological (methadone) | Waiting list control | 4 months 2 months 3 months | Biological drug use continuous Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous | % hair positive for morphine % self‐reported any injection % self‐reported heroin injection | |

| Prison | Methadone | Waiting list control. | At between 7 and 10 months At 50 weeks | Biological drug use continuous Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous | Heroin use Re‐incarceration Treatment retention Employment | |

|

| Prison | Counselling + methadone initiation pre‐release(a) and post‐release (b) | Counselling only | 1 month 3 months 6 months 12 months | Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous Criminal activity dichotomous | % positive for urine opioids % positive for urine cocaine % self‐reported 1 or more days heroin n used heroin for entire 180‐day follow‐up period Re‐incarcerated Self‐reported criminal activity |

| Prison | Prison based levo alpha acetyl methanol and transfer to methadone after release | untreated controls | During 9 months | Biological drug use dichotomous Self‐report drug use dichotomous Criminal activity dichotomous | Heroin use Arrest Re incarceration Frequency of illegal activity Admission drug use Average weekly income | |

| Prison | Naltrexone | Methadone | 6 months | Criminal activity continuous Criminal activity dichotomous Self‐report drug use continuous | Mean days of criminal activity % re‐incarcerated Mean days of heroin use Mean days of benzodiazepine use Mean days of amphetamine use | |

| Community | Pharmacological (diamorphine) | Methadone | 12 months | Criminal activity dichotomous | % self‐reported criminal activity % police‐recorded offences | |

| Prison | Buprenorphine | Methadone | 3 months | Criminal activity dichotomous Self‐report drug use continuous Self‐report drug use dichotomous | % re‐incarcerated % arrested for property crime % arrested for drug possession Mean days of heroin use % any heroin/opioid use |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Drug use (objective) Show forest plot | 3 | 300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.52, 0.97] |

| 2 Drug use community setting Show forest plot | 2 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.35, 1.09] |

| 3 Drug use secure establishment Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4 Drug use self reported dichotomous Show forest plot | 3 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.22, 0.81] |

| 5 Drug use self reported continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6 Criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Arrests | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.32, 1.14] |

| 6.2 Re‐incarceration | 3 | 142 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.19, 0.56] |

| 7 Criminal activity continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Self report drug use dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Self‐report drug use dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Self report drug use continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 Re‐incarceration dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Reincarceration | 2 | 114 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.19, 0.69] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Self reported drug use dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 Self reported drug use continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3 Criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 re incarceration | 1 | 116 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.83, 1.88] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 arrest | 1 | 825 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.03, 1.51] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 self reported drug use continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2 criminal activity dichotomous Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 re incarceration | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.37, 3.26] |

| 3 criminal activity continuous Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |