Intervenciones con ejercicios y régimen dietético combinados para la prevención de la diabetes mellitus gestacional

References

Referencias de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios excluidos de esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios en espera de evaluación

Referencias de los estudios en curso

Referencias adicionales

Referencias de otras versiones publicadas de esta revisión

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 144 women were randomised. Setting: The Resident Obstetric Clinic in Charlotte, North Carolina, USA (recruitment from October 2005 to April 2007). Inclusion criteria: women who established antenatal care at 6 to 16 weeks gestation, were aged between 18 and 49 years, who received all antenatal care at the Resident Obstetrics Clinic, were English‐speaking, Spanish‐speaking or both, and had a singleton pregnancy. Exclusion criteria: women who established antenatal care at > 16 weeks gestation, were non‐English or non‐Spanish speaking, had a multiple pregnancy, had a BMI > 40 kg/m², had pre‐existing diabetes, untreated thyroid disease or hypertension requiring medication, or other medical conditions that might affect body weight, who delivered at an institution other than Carolinas Medical Centre‐Main, had a pregnancy ending in preterm birth (< 37 weeks) or who had limited antenatal care (< 4 visits). | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 57) Women underwent a complete history and physical exam with specific attention paid to pre‐pregnancy weight, current weight, height and BMI. At the initial visit women met with a registered dietitian to receive a standardised counselling session including information on pregnancy‐specific diet and lifestyle choices. Diet: counselling consisted of recommendations for a patient‐focused caloric value divided in a 40% carbohydrate, 30% protein, and 30% fat fashion. Exercise: women were instructed to engage in moderate‐intensity exercise > 3 times per week, preferably 5 times. Women also received information on the appropriate GWG using the IOM guidelines. At each routine appointment, women's weight was measured and charted on an IOM GWG Grid in front of them. The healthcare provider informed the women whether their weight was at the appropriate level. If the GWG was appropriate the women were praised and encouraged to continue their diet and exercise regimen. If their GWG was not within the guidelines, their regimen was reviewed, and they were advised on increasing/decreasing intake and exercise. Control group (n = 43) Women received routine antenatal care, which included an initial physical examination and history, routine laboratory tests, and routine visits as per ACOG standards. The only counselling of diet and exercise during pregnancy was that included in the standard ‘What to do When You’re Having a Baby’ booklet. At each routine appointment, women's weight was measured and recorded. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses for: GWG; caesarean section. Additional narrative text for: GDM: hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: pre‐eclampsia; operative vaginal birth; perineal trauma (vaginal lacerations). | |

| Notes | Funding:"Funded by a grant from the Carolina Healthcare Foundation". Declarations of interest:"The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest". The trial was terminated early due to time restrictions involved with completing a resident research project. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was performed using computer‐generated random allocation". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Study randomization was numbered and sealed in an opaque envelope. Randomization occurred in consecutive order at the time of the new obstetrical visit". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Of 144 women randomised, 44 (31%) were excluded after randomisation; therefore 100 (69%) were included in the analyses. It was unclear which groups the excluded women had been randomised to. No other losses to follow‐up were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Outcomes were not clearly pre‐specified in the methods (only total GWG and BMI change from pre‐pregnancy to before delivery were discussed in the methods). Whilst the results section details secondary outcomes including operative vaginal birth, neonatal weight, pre‐eclampsia, GDM, vaginal/perinatal lacerations and shoulder dystocia, no numeric outcome data were reported; quote: "no statistically significant differences were noted between the groups". |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 191 women were randomised. Setting: public antenatal clinic at the Obstetric Unit of the Mother‐Infant Department of Azienda Ospedaliero‐Universitaria, Policlinico di Modena, Modena, Italy (recruitment from February 2013 to June 2014). Inclusion criteria: pregnant women with a pre‐pregnancy BMI ≥ 25 kg/m², aged > 18 years, with a singleton pregnancy, between their 9th and 12th weeks of pregnancy. Exclusion criteria: chronic diseases including diabetes mellitus (first trimester glycosuria > 100 mg/dL or fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL, or random glycaemia≥ 200 mg/dL), hypertension, medical conditions or dietary supplements that might affect body weight (e.g. thyroid diseases), previous bariatric surgery, contraindications to exercise, and intent to give birth elsewhere, previous GDM, smoking habits (≥ 5 cigarettes per day). | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 96) A personalised dietary modification intervention was initiated at enrolment through a 1‐hour counselling session with a dietitian. Follow‐up visits, scheduled for the 16th, 20th, 25th and 36th weeks of pregnancy, with both the gynaecologist and dietitian, were used to promote adherence to the intervention. At each of the follow‐up visits, the women's weight was measured. In addition, women were interviewed by the dietitian about their diet and exercise habits and counselled about possible changes, when necessary. The women who did not attend the 36‐week examination received a phone call. Diet: the primary focus was decreasing the consumption of foods with a high GI and a high saturated fat content by substituting them with healthier alternatives based on the taste and preferences of the women. Personalised dietary advise included prescription of a low GI, low saturated fat diet with a total intake of 1500 kcal/day (in light of the additional physical activity intervention, 200 kcal/day for obese and 300 kcal/day for overweight women were added). The diet plan recommended to women included a wide range of plant foods, cereals, legumes and fish, with olive old as the main source of fat, and moderate to no consumption of red wine. The diet had a target macronutrient composition of 55% carbohydrates, 20% protein and 25% fat with moderately low fat levels. The recommended intake of carbohydrates was ≥ 225 g/day. Exercise: the focus was on encouraging women to develop a more active lifestyle. Women were advised to participate in 30 minutes of moderate‐intensity activity > 3 times a week. The 'talk test' was recommended to monitor exercise intensity. Control group (n = 95) At enrolment, women in the control group attended a 1‐hour counselling session with a dietitian, who provided general recommendations on diet during pregnancy, and the same physical activity advice that was given to the women in the intervention group. In accordance with the Italian Guidelines for a healthy diet and physical activity during pregnancy, the women were also provided with a booklet providing nutrition and lifestyle. The dietitian recommended that women avoid food with a high GI, reduce the consumption of food with a high saturated fat content and increase consumption of vegetables and fruit with a low GI. No specific advice about food quantities, caloric intake, meal composition or meal distribution was given. At the follow‐up visits, women in the control group were simply asked about their adherence to the suggested lifestyle. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data) for: GDM; caesarean birth; pregnancy‐induced hypertension; large‐for‐gestational age; induction of labour; GWG; behaviour changes associated with the intervention; stillbirth; gestational age at birth; preterm birth; Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes; macrosomia; small‐for‐gestational age; birthweight. Additional narrative text for: NICU admission. | |

| Notes | Funding:"The study was supported by funding from Policlinico University Hospital of Modena. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the article". Delcarations of interest:"The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The randomization list was obtained by computer‐generated random allocation with a 1:1 ratio". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The allocations were sealed in numbered white envelopes, which were kept in the midwifery facility. After eligibility was assessed, a midwife opened the next random envelope". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | The trial was described as "open"; quote: "Because of the study design, the gynaecologist and the dietitian knew the group allocation of the patient". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The obstetrician in charge of the enrolled women was blind to the allocation group. The data regarding the delivery and the newborns were collected from the clinical records by two residents who were blind to the allocation group". Though not clear whether some outcomes (such as GDM and GWG) were able to be assessed blind, we have judged risk of detection bias as low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Of 191 women randomised, 131 (69%) women were included in the analyses. Women lost to follow‐up were significantly younger, had a lower educational level and were more frequently overweight. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | The protocol, published with ClinicalTrials.gov, was modified before the preliminary analyses; the primary outcome was changed, and additional secondary outcomes were included. The reporting of outcomes is incomplete for outcomes such as NICU admission ("were very few and did not differ between the groups"). |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 2212 women were randomised. Setting: 3 major metropolitan maternity hospitals in Adelaide, South Australia (recruitment from June 2008 to December 2011). Inclusion criteria: women with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m², with a singleton pregnancy at 10 to 20 weeks gestation. Exclusion criteria: women with a multiple pregnancy, or type 1 or 2 diabetes diagnosed prior to pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 1108 randomised) Women participated in a comprehensive diet and lifestyle intervention that included diet, exercise and behavioural strategies delivered by a research dietitian and trained research assistants. Women attending a planning session with the dietitian and were provided with individualised information (meal plans, healthy recipes, simple food substitutions, options for healthy snacking and eating out and guidelines for healthy food preparation). Women were encouraged to set achievable goals for diet and exercise change, supported to make changes, and asked to self‐monitor with a workbook; they were also asked to identify barriers and assisted to develop strategies to overcome these. The information was reinforced during a visit with the dietitian at 28 weeks, and during telephone calls with a research assistant at 22, 24 and 32 weeks, and a face‐to‐face visit with a research assistant at 36 weeks. Diet: advice was consistent with the Australian standards (maintain balance of carbohydrates, fat and protein; reduce intake of foods high in refined carbohydrates and saturated fats; increase intake of fibre; aim for 2 servings of fruit, 5 servings of vegetables and 3 servings of dairy daily). Exercise: advice encouraged women to increase walking and incidental activity. Control group (n = 1104 randomised) Women received their pregnancy care according to state‐wide perinatal practice and local guidelines, which did not include routine provision of diet or exercise advice, or advice regarding GWG. | |

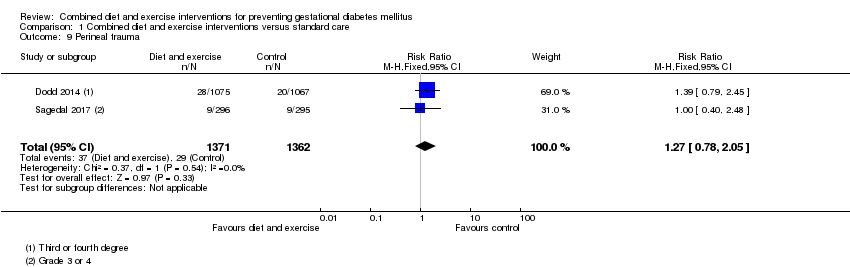

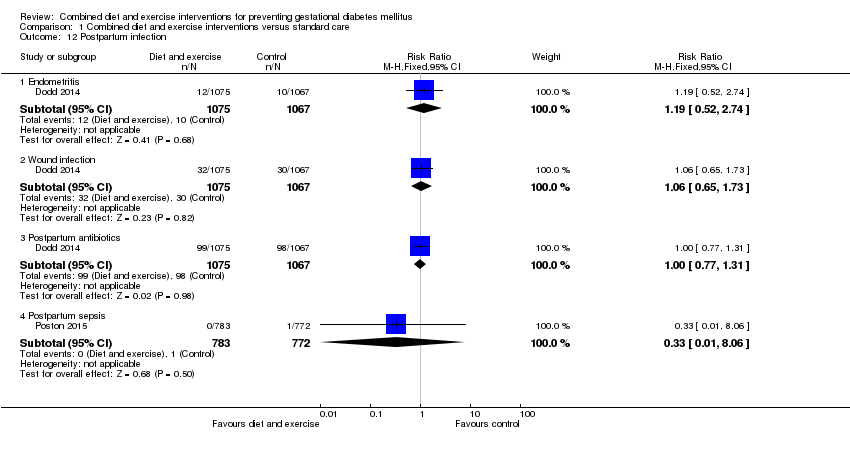

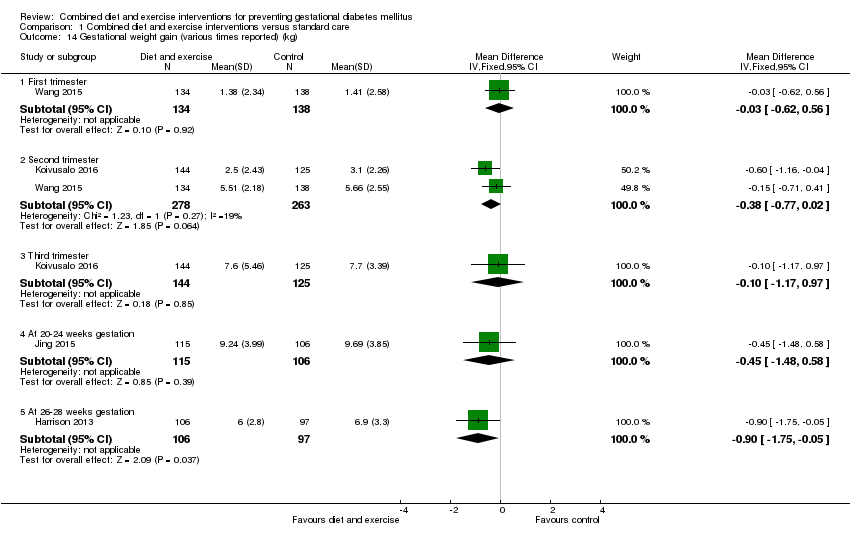

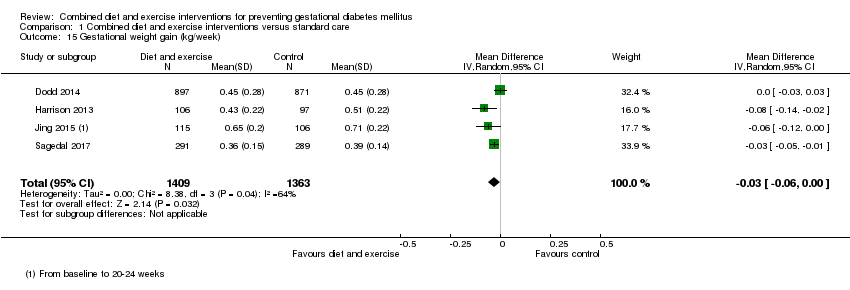

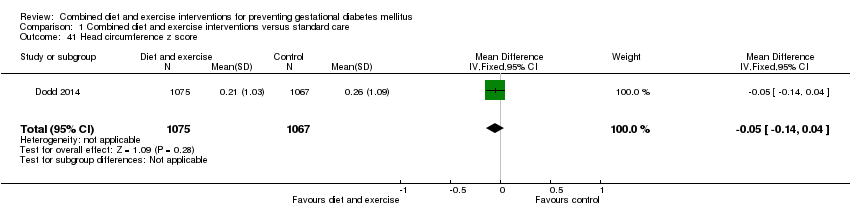

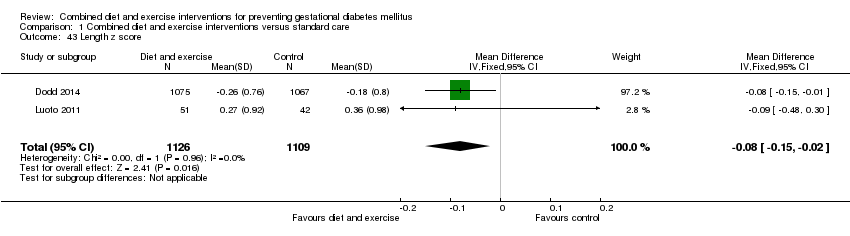

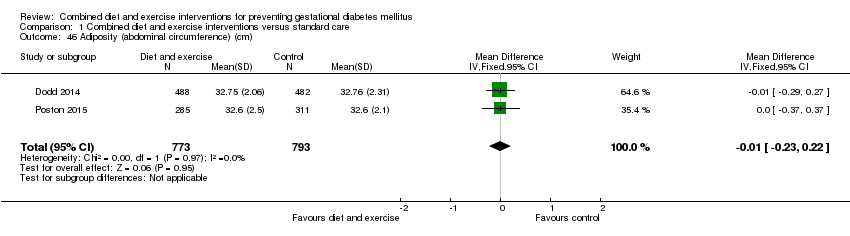

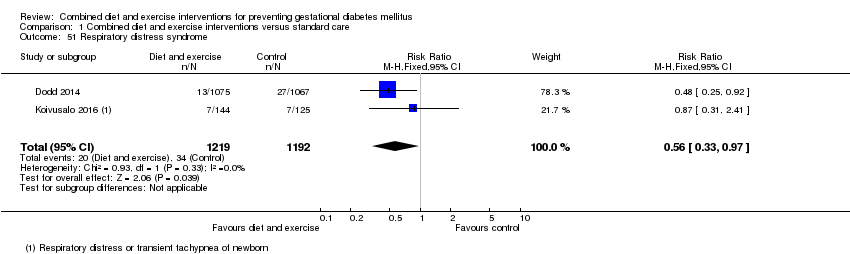

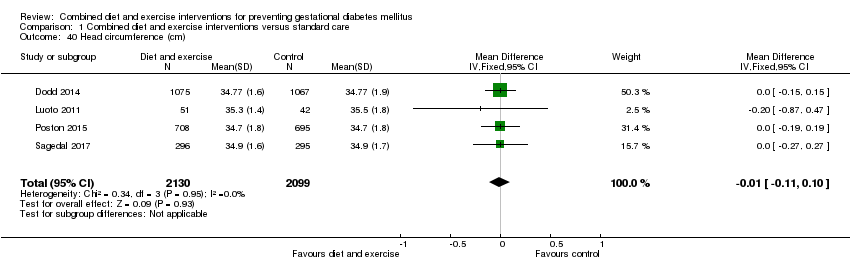

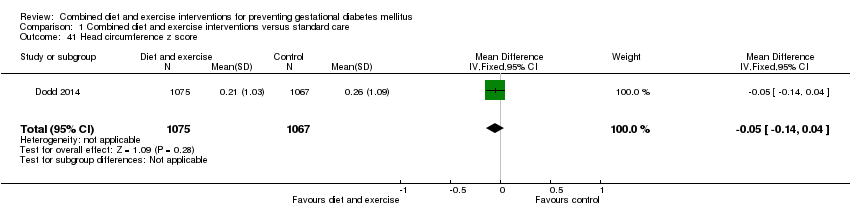

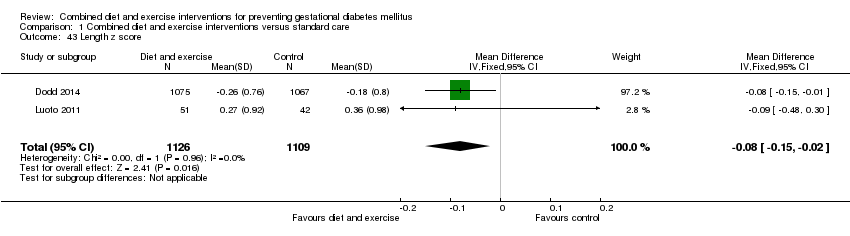

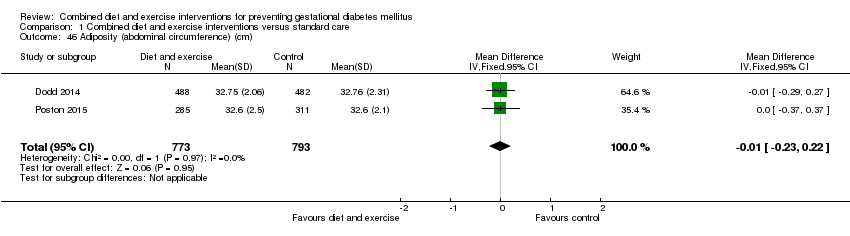

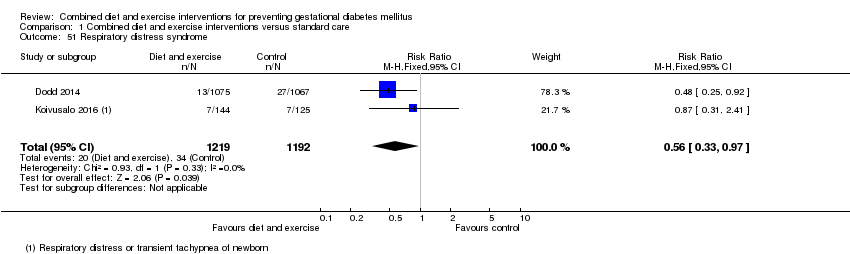

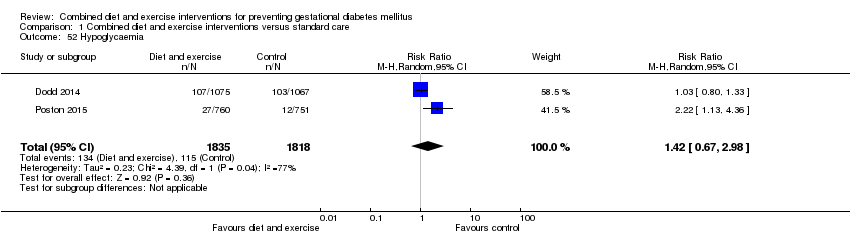

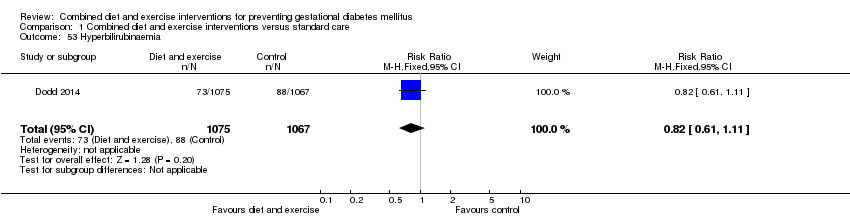

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables for): GDM; pre‐eclampsia; hypertension; caesarean birth; perinatal mortality; large‐for‐gestational age; induction of labour; perineal trauma; postpartum haemorrhage; postpartum infection; GWG; behaviour changes associated with the intervention; sense of well‐being and quality of life; stillbirth; neonatal mortality; gestational age at birth; preterm birth; Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes; macrosomia; birthweight; birthweight z score; head circumference; head circumference z score; length; length z score; ponderal index; adiposity; shoulder dystocia; bone fracture; nerve palsy; respiratory distress syndrome; neonatal hypoglycaemia; neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia; antenatal admissions; NICU admission; length of antenatal stay; length of postnatal stay (mother); length of postnatal stay (baby). Additional narrative text for: views of the intervention. | |

| Notes | Funding:"This project was funded by a four year project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australia (ID 519240). JMD is supported through a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (ID 627005). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report". Declarations of interest:"All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The computer generated randomisation schedule used balanced variable blocks in the ratio 1:1 and was prepared by an investigator not involved with recruitment or clinical care". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A research assistant counselled eligible women and then randomised them to receive lifestyle advice or standard care by telephoning the central randomisation service". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quotes: "Outcome assessors were blinded to the treatment group allocated." "After birth, a research assistant not involved in providing the intervention and blinded to treatment allocation obtained information relating to antenatal, birth, and infant outcomes from the case notes". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 2212 women were randomised; 10 withdrew consent to use data. Of the 1108 women in the intervention group, there were 25 miscarriages/terminations before 20 weeks, 3 women withdrew consent to use data, there was 1 maternal death, 4 neonatal deaths (3 due to lethal anomalies) and 5 stillbirths. Therefore, there were 1080 women (97%) included in the intervention group analyses and 1075 infants (excluding miscarriages, stillbirths and withdrawn consents). Of the 1104 women in the control group, there were 25 miscarriages/terminations before 20 weeks, 7 women withdrew consent to use data, there was 1 maternal death, 1 neonatal death and 5 stillbirths. Therefore, there were 1072 (97%) women included in the analyses, and 1067 infants (excluding miscarriages, stillbirths and withdrawn consents). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data for pre‐specified outcomes (according to published trial protocol) were reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 100 women were randomised. Setting: Egypt. Inclusion criteria: obese women at risk of GDM at their first antenatal visit. Exclusion criteria: none detailed. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (assumed that n = 50 randomised, n = 48 analysed) Women participated in a 12‐week mild physical activity program and diet control. Control group (assumed that n = 50 randomised, n = 48 analysed) Not detailed. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses for: no outcomes. Additional narrative text for: GDM, GWG, "adverse neonatal outcome". | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported. Declarations of interest: not reported. Information taken from published abstract only. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described in abstract. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described in abstract. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described in abstract. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to determine. 100 women were enrolled, however in the abstract, data are reported for 48 women per group. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to determine. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to determine. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 228 women were randomised. Setting: 3 large metropolitan tertiary teaching hospitals in Victoria, Australia (recruited from June 2008 to September 2010). Inclusion criteria: women at 12 to 15 weeks gestation, who were overweight (BMI 25 or 23 kg/m² if high‐risk ethnicity) or obese (BMI 30 kg/m²), and were at increased risk for developing GDM according to a validated risk prediction tool (based on first trimester data of women attending the hospital). Women had to agree to complete an OGTT at 28 weeks (rather than a standard GCT at GDM screening). Exclusion criteria: women with multiple pregnancies, diagnosed with type 1 or 2 diabetes, BMI > 45 kg/m², pre‐existing chronic medical condition, non‐English speaking. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 121 women randomised) Women allocated to the intervention received 4 individual sessions of a behavioural change lifestyle intervention, based on social cognitive theory. Sessions were provided in the antenatal clinic, scheduled around routine visits (14‐16, 20, 24, 28 weeks), by a health coach (exercise physiologist); however was, designed to be delivered by generic healthcare providers. The sessions provided pregnancy‐specific diet advice, simple healthy eating and physical activity messages. Simple behavioural change strategies were practiced to identify short‐term goals, increase self‐efficacy and self‐monitoring. Goals were determined by women, informed by the lifestyle messages, and included goals such as increasing fruit and vegetable intake, reducing high fat or convenience foot, and increasing physical activity frequency. Self‐monitoring strategies included use of pedometers and GWG charts based on IOM recommendations. Women received the same written information as controls, in addition to resources promoting optimal health, GWG and lifestyle. On‐going contact and support with mobile phone SMS text messages, personalised by name, were provided throughout the trial commencing from the third session, reinforcing simple health messages for diet, physical activity, behaviour change and relapse prevention; 2 healthy lifestyle postcards were also sent at 30 and 34 weeks gestation to maintain engagement and remind women of the simple health messages. Control group (n = 107 women randomised) Women received a brief, single education session based on the widely available generic Australian Dietary and Physical Activity Guidelines. Written pamphlet versions were provided. GWG was not discussed and there was no further trial support. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables) for: GDM; GWG: behaviour changes associated with the intervention; postnatal weight retention; gestational age at birth; preterm birth; birthweight; breastfeeding; postnatal BMI. Additional narrative text for: GWG: adherence to the intervention. | |

| Notes | Funding:"This project is supported by a BRIDGES grant from the International Diabetes Federation. BRIDGES, an International Diabetes Federation project is supported by an educational grant from Lilly Diabetes (Project Number: LT07‐121). The Jack Brockhoff Foundation also provided funding for this study. Helena Teede is an NHMRC research fellow. Cheryce Harrison is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship (100168) from the National Heart Foundation". Declarations of interest:"The authors declare that they have no competing interests". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Participating women were randomly assigned to intervention or control through computer‐generated randomized sequencing". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Allocation concealment was achieved by using sealed opaque envelopes". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Due to the nature of the intervention and control, it was not possible to blind women, though "pedometers were sealed to blind participants to their step count". Blinding of trial personnel is unclear, as although the authors stated: "Care providers, investigators, and outcome data analyzers were blinded to group allocation" it is unclear how this would have been successfully achieved for care providers, given women's knowledge of their group allocation. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quotes: "Care providers, investigators, and outcome data analyzers were blinded to group allocation"; "Anthropometric assessment included weight... and height measured by a registered nurse unaware of participant allocation". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 121 women allocated to intervention, 15 (12%) were lost to follow‐up, and therefore 106 (88%) were analysed. Reasons for loss to follow‐up: miscarriage (1 woman), premature birth < 26 weeks (3 women), change in circumstance (3 women), unavailable at 28 weeks (2 women), lost contact (6 women). 107 women allocated to control, 10 (9%) were lost to follow‐up, and therefore 97 (91%) were analysed. Reasons for loss to follow‐up: miscarriage (2 women), premature birth < 26 weeks (1 woman), change in circumstance (1 woman), unavailable at 28 weeks (4 women), lost contact (2 women). Follow‐up: At 6 weeks postpartum 17 (14%) intervention group women were lost to follow‐up, therefore 104 (86%) analysed; 9 (8%) control group women were lost to follow‐up, therefore 98 (92%) analysed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | With no access to a trial protocol, it was not possible to confidently assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 68 women were randomised. Setting: Baystate Medical Center and Mercy Medical Center in Western Massachusetts, USA (recruited from April 2010 to August 2011). Inclusion criteria: Hispanic women aged 18 to 40 years, with a gestational age of < 18 weeks, who were overweight or obese (pre‐pregnancy BMI ≥ 25 kg/m²) and who self‐reported participating in < 30 minutes of moderate‐intensity activity per week. Exclusion criteria: history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart disease or chronic renal disease; current medications that adversely influence glucose tolerance; not planning to continue the pregnancy to term; contraindications to participating in moderate‐intensity physical activity or a low‐fat/high‐fibre diet; self‐reported participation in ≥ 30 minutes of moderate‐intensity exercise on ≥ 3 days per week or ≥ 20 minutes of vigorous‐intensity exercise on ≥ 1 day per week; or multiple gestation (e.g. twins). | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 33 randomised) The intervention consisted of 6 in‐person behavioural counselling sessions and 5 telephone booster sessions delivered by bicultural and bilingual health educators, tailored for Hispanic women’s culture and context. All materials were available in Spanish and English and were written at a sixth‐grade reading level. Diet: women were encourage to decrease their intake of foods high in saturated fat, and to increase intake of dietary fibre (as recommended by the ADA). Health educators assessed readiness and preferences for change, consistent with the Stage of Change framework, and assisted women in developing dietary change goals. Women were provided with a low‐literacy pictured‐based food guide by which ethnic and other foods were classified based on GI/fibre content and saturated fat using the ‘traffic light’ colours and self‐monitoring logs. Activities in the follow‐up in‐person and telephone‐delivered booster sessions included review of logs, problem‐solving of challenges, introduction of new tailored materials and goal setting. Exercise: the physical activity during pregnancy guidelines of the ACOG (≥ 30 minutes of moderate‐intensity activity on most days of the week) were discussed. Women were encouraged to achieve the standards set in the guideline through increasing their walking and developing a more active lifestyle. Informed by responses to a 'Stage of Change Questionnaire', women were provided with a stage‐matched manual which included motivationally targeted materials combined with tip sheets on building social support for new behavioural patterns and strategies for overcoming barriers to physical activity. The health educators assisted the women in developing personalised physical activity goals. Women were provided with a digital pedometer and a physical activity log to track their progress Control group (n = 35 randomised) Women in the control group received standard care (no further details reported). | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data) for: GWG; behaviour changes associated with the intervention; relevant biomarker changes associated with the intervention; gestational age at birth; birthweight. Additional narrative text for: GDM; adherence to the intervention; views of the intervention. | |

| Notes | Funding: "This work was supported by CDC/ASPH S3948". Declarations of interest:"None declared". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "eligible patients were randomized... by the health educators to either a lifestyle intervention or a standard care group. Randomization was stratified by age (< 30 years, ≥ 30 years) and pre‐pregnancy BMI (25–30 kg/m², ≥ 30 kg/m²with a block size of four". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | As above; no further information provided. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Assessments were conducted by telephone, at baseline, mid‐pregnancy, and at 6 weeks postpartum by bilingual and bicultural interviewers blinded to the assigned intervention group". Though not clear whether clinical outcomes (such as GDM) were able to be assessed blind, we have judged risk of detection bias as low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Of the 33 women randomised to the intervention group, 30 (94%), 32 (97%) and 24 (75%) were available for the mid‐pregnancy, clinical outcome and postpartum assessments, respectively. Of the 35 women randomised to the control group, 29 (85%), 34 (97%) and 29 (85%) were available for the mid‐pregnancy, clinical outcome and postpartum assessments respectively. The losses at mid‐pregnancy and postpartum were associated with women being unable to be contacted via telephone; losses for clinical outcomes were associated with women being delivered off‐site. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Reporting of GDM is incomplete (only the number of cases across both groups in text) and a very limited number of clinical outcomes are reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 66 women were randomised. Setting: 2 large outpatient obstetric practices at Temple Univeresity, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA (recruitment from January 2013 to March 2014). Inclusion criteria: women aged ≥ 18 years, self‐identifying as African American, at a gestational age < 20 weeks, with a first trimester BMI of 25 to 45 kg/m², with Medicaid recipient status, and cell phone ownership (including unlimited text messaging) and Facebook membership. Exclusion criteria: women with multiple pregnancies, conditions requiring specialised nutritional care, and endorsed tobacco use. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 33 randomised) A technology‐based behavioural weight control intervention was delivered, via Facebook, telephone and text messaging and 1 in‐person consultation (at baseline). The intervention was designed to build women's motivation, support and self‐efficacy for weight‐related behaviour change, while at the same time remain responsive to low‐income African American women's social context. At their baseline visit from the health coach, women were oriented to the program, provided with an overview of behavioural change goals, an explanation of the intervention components, and a review of the schedule. Women were assigned the same scheduled for the first 12 weeks, after which the health coach prioritised the order in which goals were to be repeated until birth. The structure of the intervention implementation was as follows: baseline, in person at Temple; target: self‐weighing, behavioural goal: weigh yourself weekly; week 1: telephone; target: energy intake, behavioural goal: limit sugar‐sweetened beverages to 1 cup per day; weeks 2 and 4: telephone; target: energy intake; behavioural goal: limit junk and high fat food to no more than 1 per day; weeks 6 and 8: telephone; target: physical activity; behavioural goal: walk 5000 steps daily; weeks 10 and 12: telephone; target: energy intake; behavioural goal: stick to 1 plate of food at each meal. Women were also offered a binder with print versions of the content, if technology access was lost. Women were prompted to weigh themselves at home, and were supplied with digital scales. Diet: in addition to the specific recommendations described above, general recommendations were provided around energy intake. Women were encouraged to limit their sugar‐sweetened beverages to 1 cup per day, and stick to 1 plate of food at each meal, with low calorie beverages, and convenient, inexpensive, palatable, nutrient‐rich food, compatible with social norms suggested as alternatives (consistent with IOM recommendations). Exercise: women were encouraged to walk 5000 steps daily (gradually increasing walking by 500 steps each week), and were provided pedometers and a walking DVD. Control group (n = 33 randomised) Women received standard obstetric care which included: an initial visit in the first trimester, with comprehensive patient history, physical exam, ultrasound and blood work; follow‐up visits monthly until week 24, and every 2 to 3 weeks until week 36, with assessment of weight, blood pressure, urine protein and fetal heart rate; weekly visits from week 36 to birth. Women were also provided with information from the ACOG about optimal GWG. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data) for: GDM; caesarean birth; large‐for‐gestational age; GWG; preterm birth; small‐for‐gestational age; birthweight. Additional narrative data for: adherence to intervention; views of intervention. | |

| Notes | Funding:"This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH K23 HL106231) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA R40MC26818) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)". Declarations of interest:"At the time of the study, Dr. Herring served on scientific advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and Johnson and Johnson; Dr. Bennett served on the scientific advisory boards for Nutrisystem and the board of Scale Down; and Dr. Foster served on scientific advisory boards of Con Agra Foods, Tate and Lyle, and United Health Group. Currently, Dr. Foster is a full‐time employee of Weight Watchers International. None of these entities have provided financial support for this study nor did they have any influence on the weight control methods in this study. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was computer‐generated (by study statistician) with a 1:1 allocation ratio". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote:"randomization status was concealed in opaque envelopes prepared by the statistician". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Authors reported that "providers and clinic staff were blinded to subject randomisation to prevent contamination". However, blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No detail provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Of the 33 women randomised to the intervention, 0 were lost to follow‐up, 6 were excluded (miscarriage: 3; elective termination: 1; preterm birth: 2); therefore 27 (82%) were analysed. Of the 33 women randomised to usual care, 0 were lost to follow‐up, 4 were excluded (miscarriage: 2; preterm birth: 2); and thus 29 (88%) were analysed. Relatively high attrition in small sample. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Some discrepancies between trial registration and published report (e.g. trial registration reports primary outcome to be: change in maternal weight from early pregnancy (< 20 weeks gestation) to 6 months and 1 year postpartum), whereas main report presents primary outcome as proportion of women with excessive GWG) and additional outcomes noted in trial registration are not presented in published report. No measure of variance reported for birthweight which thus could not be included in the meta‐analysis. With no access to a trial protocol, it was not possible to further assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 480 women were randomised. Setting: not specified though authors affiliated to the Hospital Federal dos Servidores do Estado, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (recruitment from 2011 to 2015). Inclusion criteria: women aged 18 to 40 years, with ≥ 2 consecutive first trimester abortions who conceived spontaneously. Exclusion criteria: antiphospholipid antibodies, second or third trimester losses, multiple pregnancies, physical disabilities such as paraplegia, liver or kidney failure, women assigned to standard care following recommendations given to the intervention group, any condition requiring a priori anticoagulation. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n randomised not reported, n = 159 completed the trial) Women were instructed to walk briskly for ≥ 40 minutes 7 days a week, to avoid high carbohydrate index meals (such as snacks, candies, fibre‐free juices or sugar‐sweetened beverages), and to eat 2 daily servings of meat, poultry, fish or other protein rich food, starting when they decided to get pregnant and continuing until birth. Control group (n randomised not reported, n = 160 completed the trial) Women received standard care (no further detail provided). | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses for: no outcomes. Additional narrative text for: GDM; pre‐eclampsia; large‐for‐gestational age (appropriate); perinatal mortality; GWG (excessive); preterm birth (full term births); neonatal hypoglycaemia. | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported. Declarations of interest: not reported. Information taken from published abstract only. Correspondence with trial authors provided additional unpublished abstract for manuscript under review. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described in abstract. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described in abstract. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described in abstract. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Of the 480 women randomised, 319 (66%) completed the trial (159 women in the intervention group, and 160 in the control group). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to determine. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to determine. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 224 women were randomised. Setting: Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada (recruitment from July 2004 to February 2010). Inclusion criteria: non‐diabetic pregnant women (at < 26 weeks gestation), attending antenatal classes or community clinics in Winnipeg. Exclusion criteria: women with medical or obstetric contraindications to exercise during pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 112 randomised, n = 102 analysed) Diet: diet interviews and counselling were provided 2 times to each woman by a registered dietitian – at enrolment, and 2 months after enrolment. The interview was assisted with a ‘Food Choice Map’ (a computerised dietary interview tool, which consisted of a map, 91 magnetic stickers with pictures of common foods and bar codes and software modified for pregnant women). Women recalled their food intakes in a typical week, and women and dietitians placed stickers on the maps – bar codes and locations of stickers on the map represented the frequency, types and quantities of food intakes – which were scanned into the computer at the end of the interview to allow analysis instantly of calories and nutrients. Dietitians provided personalised counselling based on the interview results, pregnancy week, GWG and Health Canada Guidelines. Exercise: women were given a community‐based exercise program designed for pregnant women. Recommended exercise included walking, mild‐to‐moderate aerobic, stretching and strength exercises. An exercise regimen (3 to 5 times per week; including a weekly group exercise session and multiple home sessions) of mild‐to‐moderate exercise for 30 to 45 minutes per session was recommended. It was suggested that the exercise began between 20 to 26 weeks and ended at 36 weeks. The group sessions were held in air‐conditioned gymnasia in community centres (day time and night time classes were available). An exercise instruction video was given to women to assist with home exercise. Activity logbooks were collected weekly by the project coordinator from the women. Control group (n = 112 randomised, n = 88 analysed) Women received standard antenatal care recommended by the SOGC, and were provided with a package of up‐to‐date information on physical activity and nutrition from Health Canada. No exercise instruction or dietary intervention were provided. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables) for: GDM; caesarean birth; large‐for‐gestational age; GWG: behaviour changes associated with the intervention; gestational age at birth; birthweight. | |

| Notes | Funding:"The study was supported by operating grants from the Lawson Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada". Declarations of interest:"The authors do not have any conflict of interest regarding the content of results presented in the text". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was performed using a computer‐generated randomisation allocation table by a staff member without involvement in the study design". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "After randomisation, participants received a sealed envelope labelled with the assigned randomisation number, which contained instructions for participants". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Authors report: "The nature of the study meant that participants and study staff were not blinded to the types of interventions". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Of 112 women randomised to intervention group, 102 (91%) were included in analyses; of 112 women randomised to control group, 88 (79%) were included in analyses. 4 women were excluded from analyses due to miscarriage (1 in the control group, 3 in the intervention group). 23 women discontinued the trial in the control group and 7 in the intervention group (due to relocation, work/study, and loss to follow‐up). Suggestion of differential attrition. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | With no access to a trial protocol, it was not possible to confidently assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 113 women were randomised. Setting: Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada (recruitment from May 2009 to December 2011). Inclusion criteria: women at < 20 weeks of pregnancy, with no existing diabetes, who signed a consent form. Exclusion criteria: none detailed (3 women were excluded because of the existence of medical or obstetric contraindications for exercise during pregnancy). | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 57 women randomised) Women received a community‐based lifestyle change intervention. Dietary: women received 1‐on‐1 dietary counselling at baseline and 2 months later, using Food Choice Map software; women recalled their food intake in a typical week, and women and dietitians placed food stickers on a magnetic board (including food items, portion sizes, frequency of each food) which was scanned into the computer at the end of the session, with daily calorie intake and macronutrients analysed instantly. Nutritional recommendations were then based on the dietary intake analysis and Health Canada guidelines, with consideration of food preferences, beliefs and budgeting. GWG goals were discussed and emphasised. Women received a copy of the Food Choice Map with the agreed changes, which served as the diet plan to promote changes. The follow‐up at 2 months reinforced recommendations. Exercise: a group exercise program was delivered, in a group session or via DVD format at home. The program included mild‐to‐moderate aerobic exercise, stretching and strength exercise. Women were encouraged to exercise 3 to 5 times a week for 30 to 45 minutes, from 20 to 26 weeks to 36 weeks gestation. Women kept a log book as a motivator (attendance < 3 times at the group class, showing no interest to exercise at home or no record of exercise in the log book was considered withdrawal from the trial). Control group (n = 56 women randomised) Women received standard antenatal care, as recommended by the SOGC, and were provided with a package of current information on physical activity and healthy eating during pregnancy from Health Canada. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables) for: GDM; caesarean birth; large‐for‐gestational age; GWG: behaviour changes associated with the intervention; gestational age at birth; birthweight; Additional narrative text for: adherence to the intervention. | |

| Notes | Funding:"grant support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Lawson Foundation and the Public Health Agency of Canada". Declarations of interest:"The authors declare that there are no competing interests". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was performed using a computer‐generated randomization allocation table by a staff member without involvement in the study design". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "After randomisation participants received a sealed envelope labelled with the assigned randomisation number, which contained instructions for participants". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Authors reported that "the nature of the study meant that participants and study staff were not blinded to the types of interventions". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote:"Data on delivery route, maternal weight at delivery room, birth weight and birth weight‐related obstetric procedures (induction, forceps or caesarean section) were collected from hospital medical charts by student assistants without knowledge in study design". Though not clear whether some outcomes (such as GDM and GWG) were able to be assessed blind, we have judged risk of detection bias as low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "None of the participants discontinued during the participation". No losses or exclusions. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | With no access to a trial protocol, it was not possible to confidently assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 262 women were randomised. Setting: West China Second University Hospital, China (recruitment from September 2012 to February 2013). Inclusion criteria: women with singleton pregnancies, aged ≥ 18 years, who could understand the written Chinese language, and did not have pre‐existing diabetes. Exclusion criteria: pregnancy‐related complications or general medical disorders not associated with pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 131 randomised) Women received a lifestyle education intervention informed by the Health Belief Model. The key points of education included harms of GWG and GDM, the benefits of encouraged behaviours, the difficulties involved in change habits, and importance of belief in the efficacy of the intervention. In addition to receiving the standardised health education materials provided by the hospital as part of routine care, women received an education manual on diet and physical activity written by the research team, and had 1‐on‐1 counselling for ≥ 30 minutes with a trained graduate student, at 16 to 20 weeks gestation and 20 to 24 weeks gestation. The graduate was also available to answer questions about diet and physical activity until 20 to 24 weeks, over the phone or via a group on Tencent instant messenger. Control group (n = 131 randomised) Women received only conventional interventions such as standard health education manuals produced by the hospital. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables) for: GDM: GWG: behaviour changes associated with the intervention. | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported. Declarations of interest"The authors have no conflicts of interest". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote:"The participants were divided according to the sequence of time and randomized numbers produced by SAS version 11.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Raleigh, NC, USA)". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: "Participants and data analysts were masked to group assignment. The investigators were not masked to the assignment so that they could implement the personalized intervention for women in the intervention group". While authors reported women were blinded, blinding of women was not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Only women who finished the whole study were included in the analysis". In the intervention group, of the 131 women randomised, 115 (88%) were included in the analyses (16 did not complete the trial: 1 had abnormal blood sugar; 2 had spontaneous abortions; 11 relocated; 2 lost to follow‐up). In the control group, of the 131 women randomised, 106 (81%) were included in the analyses (25 did not complete the trial: 1 had abnormal blood sugar; 2 had spontaneous abortions; 13 relocated; 9 lost to follow‐up). Suggestion of differential attrition. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | With no access to a trial protocol, it was not possible to confidently assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 293 women were randomised. Setting: multi‐centre trial, with 2 rural municipalities: Kauhajoki and Lapua in Finland (from February 2008 to January 2014). Inclusion criteria: women who had 1 or more risk factors for GDM (BMI > 25 kg/m², previous history of GDM, previous child born at > 4.5 kg, aged greater than 40 years, family history of diabetes), or who had a venous plasma glucose concentration after 12 hours of fasting in the morning of 4.8 mmol/L, to 5.5 mmol/L, and a 2 hour‐OGTT plasma glucose < 7.8 mmol/L. [A 2‐hour OGTT was offered to all women at their first contact with maternal healthcare units during gestational weeks 8 to 12]. Exclusion criteria: women with GDM (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or 2‐hour plasma glucose ≥ 7.8 mmol/L), and women who did not want to participate in the trial for personal or professional reasons. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 155 randomised) Women received individualised, structured lifestyle counselling from specifically trained trial nurses (midwives) and dietitians, 3 times during their pregnancy (at medians of 13.3 weeks, 23.1 weeks, and 35.1 weeks). Women also attended a 2‐hour group counselling session with a dietitian at the time of enrolment. Women also visited the trial nurses at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months postpartum. Diet: for women with a pre‐pregnancy BMI ≥ 30 kg/m², the recommendation was no GWG during the first 2 trimesters. Dietary advice was based on Nordic Nutrition Recommendations and focused on optimising women's consumption of vegetables, fruit and berries, whole‐grain products rich in fibre, low‐fat dairy products, vegetable fats high in unsaturated fatty acids, fish, and low‐fat meat product, and lowering intakes of sugar‐rich foods. 'The plate model' was used during the counselling (filling half a plate with raw or cooked vegetables, one‐quarter with starchy carbohydrates (e.g. potato, rice or pasta) and one‐quarter with meat, fish, beans, eggs or other sources of protein). The aim was to achieve a total intake of 1600 to 1800 kcal a day, with 40% to 50% energy coming from carbohydrates, 30% to 40% energy from fats and 20% to 25% energy from protein. During the postpartum, breastfeeding and infant nutrition counselling were provided. Women filled out 3‐day food diaries every 3 months throughout the trial. Exercise: women were encourage to achieve a minimum of 150 minutes (30 minutes 5 times a week, or 50 minutes 3 times a week) of moderate‐intensity physical activity per week, and to adopt an overall active lifestyle (moderate‐intensity exercise was defined as exercise during which the women became at least slightly out of breath and perspired but were still able to talk or a level equalling 11 to 15 on Borg's visual scale of perceived exertion). Women and trial nurses (midwives) planned, and during the follow‐up updated, an individual physical activity program. Women received pedometers, with a recommendation of a minimum of 10,000 steps a day. Women had access, free of charge, to public swimming pools and/or guided exercise groups once a week provided by the municipalities. Where exercise goals were not met, women were instructed to book in with the physical activity advisor. Women completed physical activity log books. Control group (n = 138 randomised) Women received general information leaflets on diet and physical activity like those provided by local Primary Health Care centres/antenatal clinics at the time of enrolment. During their pregnancy, women visited the trial nurse 3 times, to make measurements, obtain blood samples, and administer questionnaires, as well as antenatal clinics according to standard practice. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables) for: GDM; pre‐eclampsia; hypertension (pregnancy‐induced hypertension, essential hypertension); caesarean section; GWG; behaviour changes associated with the intervention; relevant biomarker changes associated with the intervention; gestational age at birth; macrosomia; birthweight; birthweight z score; length; respiratory distress syndrome; antenatal visits. | |

| Notes | Funding:"This study was funded by the Ahokas Foundation, the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Disease, Special State Subsidy for Health Science Research of Helsinki University Central Hospital, Samfundet Folkhalsan, The Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation, the State Provincial Office of Southern Finland, and The Social Insurance Institution of Finland. The funders have not had any role in designing or conducting the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication". Declarations of interest:"No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "In the randomization process, we used randomly permuted blocks stratified by risk factors (BMI ≥30 kg/m², history of GDM)". Not stated how randomly permuted blocks were generated; thus judged to be unclear risk of selection bias. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote:"The randomisation was performed by a study nurse and by dispensing the next sequentially numbered subject code and opening the corresponding code envelope, which included the intervention arm to be assigned to the subject". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Blinded‐study physicians reviewed participants' obstetric records and confirmed maternal and neonatal diagnosis". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Of 155 women randomised to the intervention group, 11 (7%) were lost; thus 144 (93%) were included in the analyses; of the 138 women randomised to the control group, 13 (9%) were lost; thus 125 (91%) were included in the analyses. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The trial has reported on perinatal outcomes; the trial protocol indicates that 12‐month follow‐up is also complete (this was not reported on), and that there will be ongoing follow‐up to 10 years for mothers, fathers and children. The protocol indicates additional outcomes which have not yet been reported (including maternal quality of life, cost‐effectiveness, prevention of maternal type 2 diabetes 1 year after birth, small‐for‐gestational age and neonatal hypoglycaemia). |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 60 women were randomised. Setting: multi‐centre trial, with 2 rural municipalities: Kauhajoki and Lapua in Finland (recruitment from April 2005 to May 2006). Inclusion criteria: women who had 1 or more risk factors for GDM (BMI > 25 kg/m², previous history of GDM, previous child born at > 4.5 kg, aged > 40 years, family history of diabetes), or who had a venous plasma glucose concentration after 12 hours of fasting in the morning of 4.8 mmol/L, to 5.5 mmol/L, and a 2 hour OGTT plasma glucose of < 7.8 mmol/L. [a 2‐hour OGTT was offered to all women at their first contact with maternal healthcare units during gestational weeks 8 to 12] Exclusion criteria: women with GDM (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L or 2‐hour plasma glucose ≥ 7.8 mmol/L), and women who did not want to participate in the trial for personal or professional reasons. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 30 randomised; n = 27 analysed) Diet: dietary advice tailored to each woman individually on 6 occasions was provided; the nurse in the healthcare centres had on average 13 appointments with the intervention women. Women were encouraged to eat a diet rich in vegetables, berries and fruits, and to use low‐fat dairy products, low‐fat meat, soft margarines and vegetable oils and whole grain products (with a goal of carbohydrate 50% to 55% energy, fibre 15 g/1000 kcal, fat 30% energy %, saturated fat < 10% energy, and protein 15% to 20% energy). Recommendation for energy intake was 30 kcal/kg/day for normal weight women and 25 kcal/kg/day for overweight women. Exercise: moderate‐intensity physical exercise during pregnancy was encouraged; the women had 6 sessions of exercise counselling with the physiotherapist. During the sessions the physiotherapist motivated the women to continue exercising during pregnancy or to start exercising, and gave written instructions for exercise and self‐care. The goal of the exercise intervention was 30 minutes of daily physical activity if the woman previously exercised < 2.5 hours per week, and 45 minutes if the woman already engaged in 2.5 hours per week. Recommended types of exercise included brisk walking, Nordic walking, swimming, cycling, and cross‐country skiing. (If the BMI of the woman was > 30 kg/m² and the woman had not been active, exercise was started with 15 minutes per day 3 times a week). Control group (n = 30 randomised; n = 27 analysed) All women were given general information on diet and physical activity to decrease the risk of GDM during pregnancy as part of routine care. Women were followed up in the antenatal clinical at 1‐month intervals according to standard care. For all women, dietary information was collected 3 times during pregnancy, and women returned a self‐reported exercise history twice, and a monthly questionnaire of activity. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other tables data) for: GDM; GWG; relevant biomarkers associated with the intervention; birthweight. Additional narrative text for: pre‐eclampsia; caesarean birth; induction of labour; perineal trauma (lacerations); gestational age at birth; macrosomia; respiratory distress; hyperbilirubinaemia (jaundice requiring phototherapy); NICU admission. | |

| Notes | Funding:"This study was funded by Seinäjoki Central Hospital and Kuopio University Hospital, University of Eastern Finland and municipalities of Kauhajoki, Lapua i.e. employers of the authors mentioned on the title page. The study was supported by EVO funding from Kuopio University Hospital and South Ostrobothnia Hospital District". Declarations of interest:"The authors declare that they have no competing interests". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "These high‐risk women were randomly assigned to the lifestyle intervention group... or to the close follow‐ up group... by the study physician in the Central Hospital with the use of a computed randomisation list". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | As above, and "The health care nurses who scheduled the study visits did not have access to the randomisation list". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No blinding, trial described as "open". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Trial described as "open". No further information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | 60 women were randomised; 54 women (90%) were analysed. 3 women dropped out from each group (4 due to early miscarriage, 1 with a twin pregnancy, and 1 woman moved away). No detail of whether the characteristics of the women lost to follow‐up differed from those analysed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | For the baseline characteristics, and a number of other outcomes, data were reported by groups, with the P values reported as "NS" (indicating non‐significance). For a number of outcomes, the data were not presented ("There was no statistically significant difference between the randomised groups in terms of pre‐eclampsia, induction of labor, lacerations, Cesarean deliveries (data not shown)".) |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Pre‐pregnancy weight in the intervention group tended to be higher (P = 0.061) with "all women weighing over 100 kg" being in the intervention group. Women in the control group tended to have a higher educational status (P = 0.080). |

| Methods | Cluster‐randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 14 municipalities, with 640 women, were randomised. Setting: maternity clinics of primary healthcare centres of 14 municipalities in Pirkanmaa region in south‐western Finland. All 14 municipalities with ≥ 70 annual deliveries were recruited to the trial (recruitment from October 2007 to December 2008). Inclusion criteria: pregnant women with ≥ 1 of the following risk factors: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m² based on measured height and self‐reported pre‐pregnancy weight, GDM or any signs of glucose intolerance or newborn macrosomia in any earlier pregnancy, type 1 or 2 diabetes in first or second degree relatives, aged ≥ 40 years. Exclusion criteria: ≥ 1 of 3 baseline OGTT measurements abnormal (fasting blood glucose ≥ 5.3 mmol/L, ≥ 10.0 mmol/L at 1 hour, and ≥ 8.6 mmol/L at 2 hours), pre‐pregnancy type 1 or 2 diabetes, unable to speak Finnish, < 18 years old, multiple pregnancy, a physical restriction preventing physical activity, substance abuse, treatment or clinical history of psychiatric illness. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 7 municipalities) The intervention continued from the first maternity clinic (8 to 12 weeks) to 37 weeks gestation. At the first visit, recommendations for GWG were discussed and an appropriate GWG graph selected to guide the woman in her GWG. The primary physical activity counselling was implemented at 8 to 12 weeks, and the primary dietary counselling session at 16 to 18 weeks. Physical activity counselling was enhanced at 4, and diet counselling at 3, subsequent visits. If the OGTT at 26 to 28 weeks was pathological, women were referred to other healthcare specialists. Diet: the goal of diet counselling was to help women achieve a healthy diet (≤ 10% saturated fat, 5% to 10% polyunsaturated fat, 25% to 30% total fat, and < 10% saccharose of total energy intake, and 25 g/day to 35 g/day fibre). Women were advised to consume vegetables, fruits and berries ≥ 5 portions a day, to select mostly high‐fibre bread and wholemeal products, to select mostly fat‐free or low‐fat versions of milk and milk products, to eat fish ≥ twice per week, to use moderate amounts of soft table spreads on bread, oil‐based salad dressings in salad and oil in cooking/baking, to consume seldom (small portions) of foods high in fat, and to consume seldom (small portions) snacks with high levels of sugar and fat. Counselling cards helped nurses to standardise counselling. The women used follow‐up notebooks to set their individualised plans and to keep a record of adherence. Physical activity counselling: aims were to increase leisure time for those women not fulfilling recommendations, or to adjust/maintain time for women who were fulfilling recommendations. The minimum weekly leisure time physical activity dose in the plan was 800 MET minutes. Women were offered an opportunity to participate in monthly group exercise sessions. Control group (n = 7 municipalities) Women received no counselling beyond usual care – which included some dietary counselling and follow‐up of GWG, but little on physical activity. | |

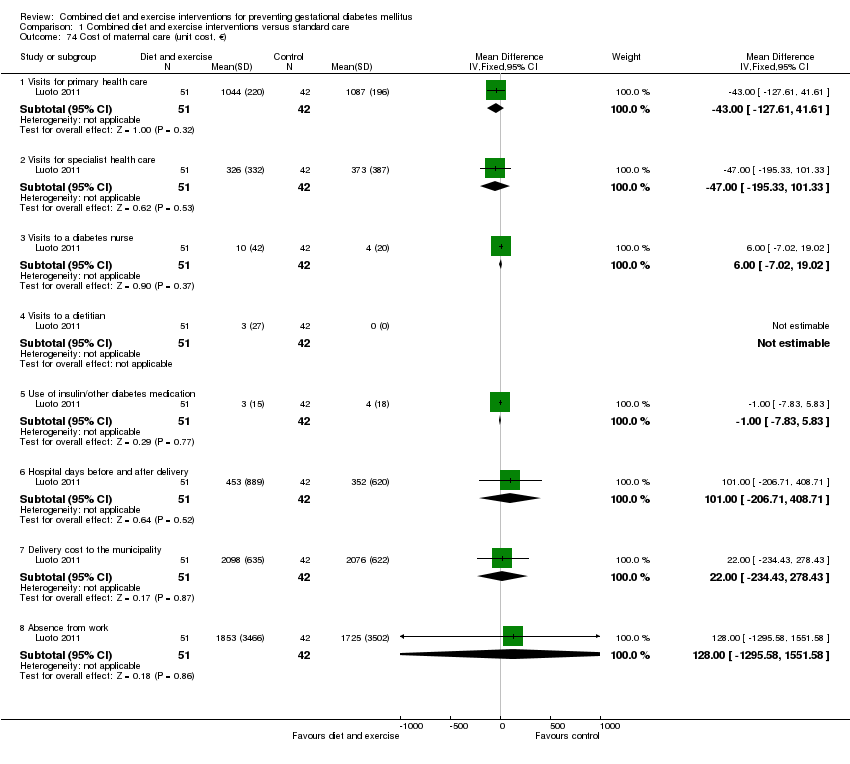

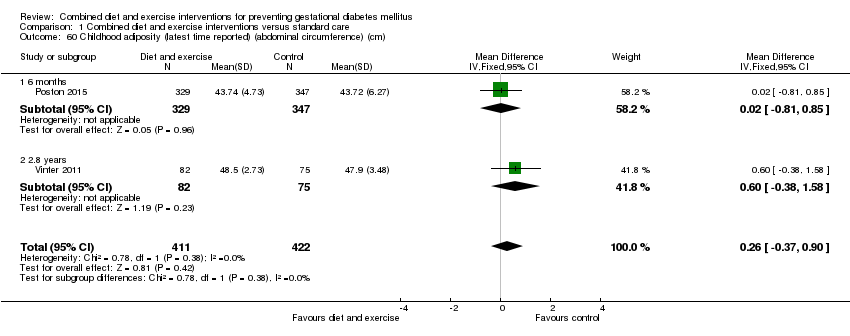

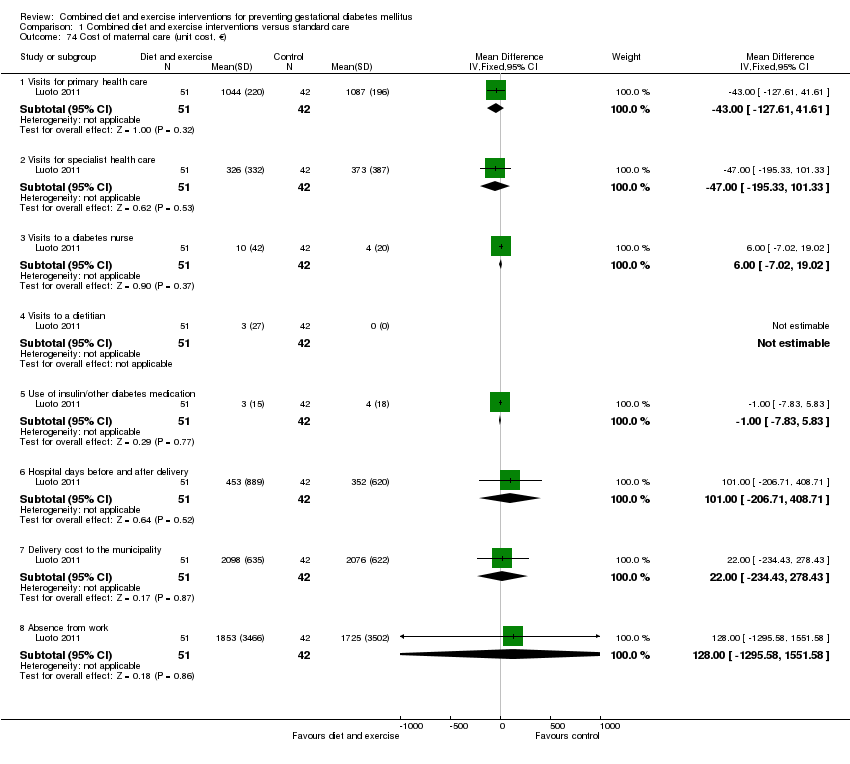

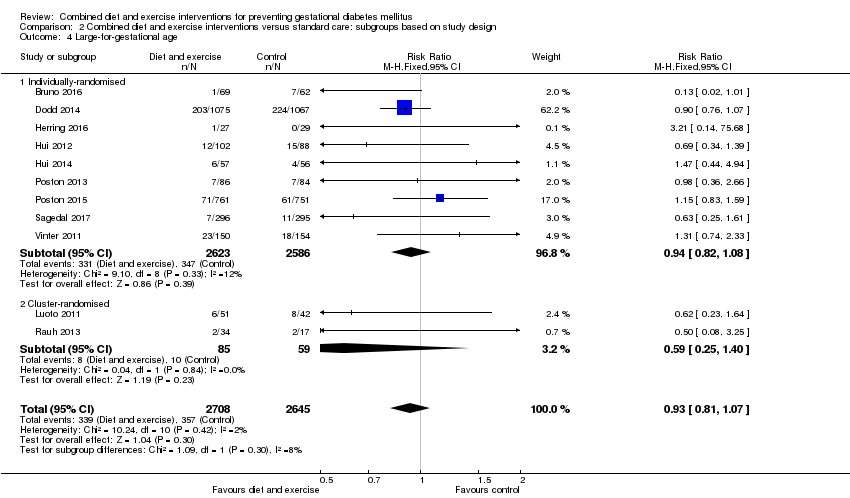

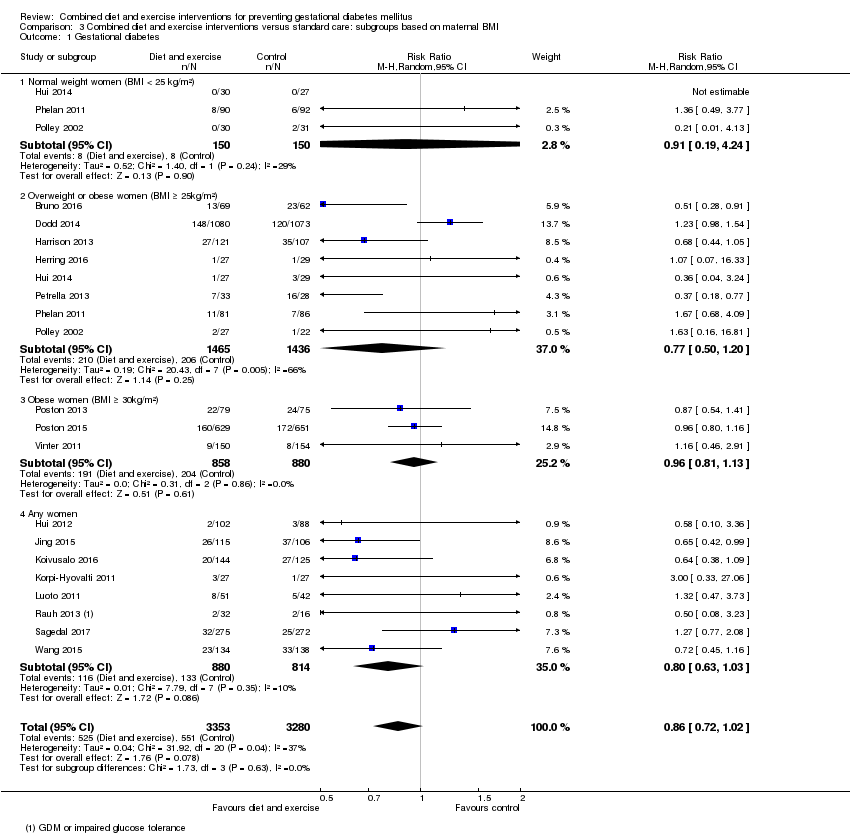

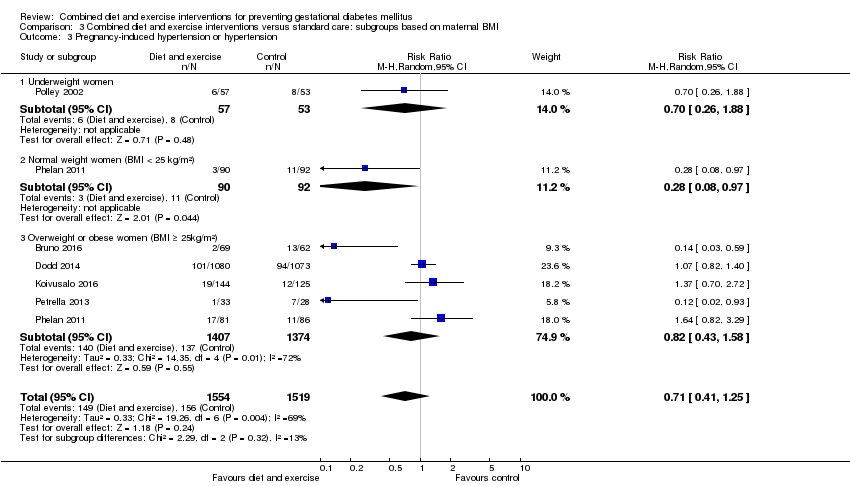

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables) for: GDM; pre‐eclampsia; large‐for‐gestational age; GWG; behaviour changes associated with the intervention; relevant biomarkers associated with the intervention; sense of well‐being and quality of life; gestational age at birth; macrosomia; small‐for‐gestational age; birthweight; birthweight z score; head circumference; length; length z score; ponderal index; costs to families associated with management provided; costs associated with the intervention; costs of maternal care; costs of offspring care. Additional narrative text for: adherence to the intervention; costs associated with the intervention. | |

| Notes | Funding:"The main sources of funding in this study are (Finnish) Diabetes research fund, Competitive research funding from Pirkanmaa hospital district, Academy of Finland, Ministry of Education and Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript". Declarations of interest:"The authors have declared that no competing interests exist". ICC of 0.12 was used in the analyses. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "In the randomization process, participating municipalities were first pairwise matched with regard to annual number of births, size and socio‐economic level of the population, estimated incidence of GDM, and urbanity level. Municipalities were then randomized by computer". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: "An inevitable limitation is also that the women and the nurses in the usual care group could not be blinded for the purpose of the study, which may have resulted in changes in their health behavior or counseling practices". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 14 clusters were randomised and all included in the analyses. Of the 343 women in the intervention group and 297 women in the control group that agreed to participate (after having been screened for eligibility), 81 (24%) in the intervention group and 93 (31%) in the control group were excluded due to abnormal OGTT results at baseline (and 16 and 8 respectively due to miscarriage). The final number of women in the analyses, after further loss to follow‐up (27 in the intervention group and 16 in the control group) was 219 in the intervention group and 180 in the control group. Thus, of the women considered preliminarily eligible, who consented to participate, 219 (64%) were followed up in the intervention group, and 180 (60%) in the control group; of the women who received the allocated intervention, 219 (89%) were followed up in the intervention group and 180 (92%) in the control group. For some outcomes "n Missing" is reported in the tables – it is unclear however from which groups the missing data are from (for example, GWG "n Missing" = 31, and it is unclear if these women are from the intervention or control groups). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The published trial protocol indicates that data for a number of additional outcomes including other perinatal outcomes (caesarean section and need for induction of labour), maternal quality of life, and direct and indirect costs during pregnancy have been (or will be) collected; however outcome data for these outcomes were not reported in this manuscript. In addition, 1‐year follow‐up data are expected; the manuscript does indicate that these will be published in a later report. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | There were more women in the intervention group with high education than in the usual care group. The trial's statistical methods appear to take clustering into account, and a number of individual level characteristics such as education (unadjusted and adjusted analyses were performed). |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 63 women were randomised Setting: Obstetric Unit at the Mother‐Infant Department of Policlinico Hospital, University of Modena, Modena, Italy (recruitment from April 2011 to October 2011). Inclusion criteria: pregnant women with a pre‐pregnancy BMI ≥ 25 kg/m², aged > 18 years, with a single pregnancy during their 12th week. Exclusion criteria: twin pregnancy, chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes, chronic hypertension, untreated thyroid diseases), GDM in previous pregnancies, smoking during pregnancy, previous bariatric surgery, engagement in regular physical activity, use of dietary supplements or herbal products known to affect body weight, other medical conditions that might affect body weight, plans to deliver outside the Birth Centre. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 33) Women received a "Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC) Program", with specific follow‐up for adherence at the 16th, 20th, 28th and 36th week. Diet: women were prescribed a diet consisting of 1700 kcal/day for overweight women and 1800 kcal/day for obese women, with 3 main meals and 3 snacks. The primary focus of the diet was decreasing high‐GI foods and substituting with healthier alternatives; with a second goal being redistribution of the number of meals throughout the day, with the last 2 snacks eaten after dinner to avoid hypoglycaemia at night. The target macronutrient composition was 55% carbohydrate (80% complex with low GI and 20% simple), 20% protein (50% animal and 50% vegetable), 25% fat (12% monounsaturated, 7% polyunsaturated, 6% saturated); the daily intake of carbohydrates was ≥ 225 g/day. The diet was introduced after randomisation by a gynaecologist and dietitian, with a 1‐hour counselling session about appropriate GWG at term for preventing unfavourable outcomes. Women completed Food Frequency Questionnaires at baseline and the 36th week. Exercise: the exercise component focused on developing a more active lifestyle, with women advised to participate in 30 minutes of moderate‐intensity activity ≥ 3 days a week. Women were provided with a pedometer to wear during each walking session for assessment of adherence, and were told to consider using the ‘talk test’ (to be able to maintain a conversation during activity). Control group (n = 30) Women received a simple nutritional booklet about lifestyle (in agreement with Italian Guidelines for healthy diet during pregnancy) and attended their regularly scheduled visits with their obstetrician until birth. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables) for: GDM; pregnancy‐induced hypertension; caesarean birth; induction of labour; GWG; preterm birth; behaviour changes associated with the intervention. Additional narrative text for: large‐for‐gestational age; perineal trauma; postpartum haemorrhage; Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes; NICU admission. | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported. Declarations of interest:"The authors report no conflicts of interest". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization list was obtained by using a computer‐generated random allocation in blocks of three". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The numbers were sealed in numbered white envelopes. After eligibility assessment, the midwife open the next envelope". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Two women randomized to Controls later withdrew their consent for the study. Therefore, the remnant participants were 33 in the Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes group and 28 in the Controls". |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | A number of outcomes are reported incompletely as "similar" between groups, or "no statistically significant differences". |

| Other bias | Low risk | No obvious sources of other bias identified. |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 401 women were randomised. Setting: 6 obstetric offices in Providence, Rhode Island, USA (recruitment from 2006 to 2008). Inclusion criteria: women with a gestational age between 10 to 16 weeks, with a BMI between 19.8 kg/m² to 40 kg/m², who were non‐smoking adults (≥ 18 years), were fluent in English, had access to a telephone, and who had a singleton pregnancy. Exclusion criteria: women with self‐reported major health or psychiatric disease, with weight loss during pregnancy, or with a history of ≥ 3 miscarriages. | |

| Interventions | Intervention group (n = 201) Women in the intervention group received all aspects of standard care plus a behavioural lifestyle intervention designed to prevent excessive GWG; no intervention was provided postpartum. The intervention included 1 face‐to‐face visit with an interventionist at the onset of treatment who discussed appropriate GWG. There was an emphasis on decreasing high‐fat foods, increasing physical activity and daily self‐monitoring of eating, exercise, and weight. Women received 3 brief supportive phone calls from the dietitian during the intervention. Women who were over or under GWG guidelines during any 1‐month interval received additional phone calls (2 calls per month) that provided structured meal plans, and specific goals. Diet: recommendation: calorie goals (20 kcal/kg). Exercise: recommendation: 30 minutes walking most days of the week. Control group (n = 200) Women attended regular scheduled visits to antenatal care providers, occurring monthly until 28 weeks gestation, bi‐weekly from 28 to 36 weeks gestation, weekly until birth, and at 6 weeks postpartum. Women received standard nutrition counselling provided by physicians, nurses, nutritionists, and counsellors. Women were weighed by nurses at each visit, and attended a brief (15 minute) face‐to‐face visit at trial entry with the trial interventionist and received trial newsletters at 2‐month intervals during pregnancy and postpartum, providing information about pregnancy related issues (antenatal vitamins and maternity clothes), to improve retention in the trial. | |

| Outcomes | Data in meta‐analyses (or other data tables) for: GDM; pre‐eclampsia; hypertension; caesarean birth; GWG; behaviour changes associated with the intervention; sense of well‐being and quality of life; postnatal weight retention; return to pre‐pregnancy weight; gestational age at birth; preterm birth; macrosomia; birthweight. Additional narrative text for: breastfeeding. | |

| Notes | Funding:"Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant DK071667)."The National Institutes of Health was not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript". Declarations of interest:"None of the authors had a conflict of interest". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was computer‐generated (by the study statistician) in randomly varying block sizes and stratified by clinic and BMI category". |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "allocation was concealed in opaque envelopes prepared by the study statistician". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Authors report "Clinic staff and physicians were blinded to subject randomisation to prevent contamination". However, blinding of women and trial personnel not considered feasible in view of the intervention and control. |