Reemplazo de catéteres venosos periféricos por indicación clínica versus reemplazo sistemático

References

Referencias de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios excluidos de esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios en espera de evaluación

Referencias adicionales

Referencias de otras versiones publicadas de esta revisión

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Methods | Study design: single‐centre RCT Method of randomisation: computer‐generated Concealment of allocation: sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Country: England, UK Number: 47 patients in general medical or surgical wards. Clinically indicated: 43 catheters were inserted in 26 participants. Routine replacement: 41 catheters were inserted in 21 participants Age: clinically indicated 60.5 years (15.5); routine replacement 62.7 years (18.2) Sex (M/F): clinically indicated 15/11; routine replacement 14/7 Inclusion criteria: hospital inpatients receiving crystalloids and drugs Exclusion criteria: not stated | |

| Interventions | Clinically indicated: catheters were removed if the site became painful, the catheter dislodged or there were signs of PVT Routine replacement: catheters were replaced every 48 h | |

| Outcomes | Primary: incidence of PVT defined as "the development of two or more of the following: pain, erythema, swelling, excessive warmth or a palpable venous cord" | |

| Notes | PVT was defined as "the development of two or more of the following: pain, erythema, swelling, excessive warmth or a palpable venous cord". However, in the discussion, the trial author stated that "even a small area of erythema was recorded as phlebitis" (i.e. only 1 sign). It is unclear what proportion of participants were on continuous infusion. Catheters were inserted "at the instruction of the principal investigator". "All patients were reviewed daily by the principal investigator, and examined for signs of PVT at the current and all previous infusion sites". | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Comment: computer‐generated (personal communication with trial author) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Comment: sealed envelopes (personal communication with trial author) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Evidence: "Forty‐seven patients were included in this randomised, controlled, unblinded study" Comment: classified as high risk because the investigator was involved in all stages of the study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Evidence: "Forty‐seven patients were included in this randomised, controlled, unblinded study" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Comment: in this small sample, there were five fewer participants in the routine replacement group. No explanation was provided for the unequal sample size. No dropouts or loss to follow‐up were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: Phlebitis was the only outcome planned. |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: the chief investigator allocated participants and was responsible for outcome evaluation. No sample size calculation |

| Methods | Study design: single‐centre RCT Method of randomisation: not stated. Concealment of allocation: sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Country: India Number: 42 patients in surgical wards. Clinically indicated: 21. Routine replacement: 21 Age: clinically indicated 40.2 years (15.0); routine replacement 42.9 years (15.0) Sex (M/F): clinically indicated 17/4; routine replacement 16/5 Inclusion criteria: hospital inpatients admitted for major abdominal surgery Exclusion criteria: receiving total parenteral nutrition, duration of therapy expected to be < 3 days, if a cannula was already in situ, terminally ill patients | |

| Interventions | Clinically indicated: catheters were removed if the site became painful, the catheter dislodged or there were signs of PVT Routine replacement: catheters were replaced every 48 h | |

| Outcomes | Primary: incidence of PVT defined as "the development of two or more of the following: pain, erythema, swelling, excessive warmth or a palpable venous cord" | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Evidence: "The patients were allocated to either study or the control group using block randomisation method. The patients were divided into 6 blocks with block sizes of 8 or 10 or 12 arranged randomly". Comment: how the sequence was generated was not stated. With group sizes of 21 per group, that block sizes make no sense. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Evidence: "Group name was placed (on) an opaque serially numbered sealed envelope (SNOSE)." Comment: presumably the trial authors meant 'in' an opaque serially numbered sealed envelope ‐ based on subsequent information. The investigator was responsible for allocation. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "..unblinded study" Comment: neither participants nor clinical personnel were blinded but review authors do not believe this would introduce bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Evidence: "...unblinded study" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: data for all participants were available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: stated outcomes were reported but original protocol not sighted |

| Other bias | High risk | Extreme results: in this small trial, 100% of participants in the clinically indicated group developed phlebitis compared with 9% in the 2‐day change group, which suggests that chance or other unknown bias affected results. |

| Methods | Study design: single‐centre RCT Method of randomisation: computer‐generated Concealment of allocation: telephone service | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Number: 362 patients requiring IV therapy in general medical or surgical wards. Clinically indicated: 280 catheters were inserted in 185 participants. Routine replacement: 323 catheters were inserted in 177 participants Age: clinically indicated 62.7 years (15.5); routine replacement 65.1 years (17.3) Sex (M/F): clinically indicated 82/103; routine replacement 81/91 Inclusion criteria: > 18 years, expected to have an IVD, requiring IV therapy for ≥ 4 days Exclusion criteria: patients who were immunosuppressed, had an existing BSI or those in whom an IVD had been in place for > 48 h | |

| Interventions | Clinically indicated: catheters were removed if there were signs of phlebitis, local infection, bacteraemia, infiltration or blockage Routine replacement: catheters were replaced every 72‐96 h | |

| Outcomes | Primary: phlebitis per person and per 1000 IVD days (defined as ≥ 2 of the following: pain, erythema, purulence, infiltration, palpable venous cord); IVD‐related bacteraemia Secondary: hours of catheterisation; number of IV devices; device‐related BSI; infiltration; local infection | |

| Notes | Approximately 75% of participants were receiving a continuous infusion | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Patients were randomly assigned (computer generated)" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Assignment was concealed until randomisation by use of a telephone service" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Open (non‐blinded) parallel group RCT" Comment: neither participants nor clinical personnel were blinded but review authors do not believe this would introduce bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Comment: although laboratory staff were blinded for microbiological outcomes, there were no BSIs; consequently, all other outcome assessment was at high risk of bias. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: results from all enrolled participants were reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: the protocol was available. All nominated outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: significantly more participants in the routine‐change group received IV antibiotics (73.1% versus 62.9%) |

| Methods | Study design: multicentre RCT Method of randomisation: computer‐generated, stratified by site Concealment of allocation: allocation concealed until eligibility criteria was entered into a hand‐held computer | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Number: 3283 patients requiring IV therapy in general medical or surgical wards. Clinically indicated: 1593 participants. Routine replacement: 1690 participants Age: clinically indicated 55.1 years (18.6); routine replacement 55.0 years (18.4) Sex (M/F): clinically indicated 1022/571; routine replacement 1034/656 Inclusion criteria: patients, or their representative able to provide written consent; > 18 years, expected to have an IVD in situ, requiring IV therapy for ≥ 4 days Exclusion criteria: patients who were immunosuppressed, had an existing BSI or those in whom an IVD had been in place for > 48 h or it was planned for the catheter to be removed < 24 h | |

| Interventions | Clinically indicated: catheters were removed if there were signs of phlebitis, local infection, bacteraemia, infiltration or blockage Routine replacement: catheters were replaced every 72‐96 h | |

| Outcomes | Primary: phlebitis during catheterisation or within 48 h of removal (defined as ≥ 2 of the following: pain, erythema, swelling, purulent discharge, palpable venous cord) Secondary: CRBSI, all‐cause BSI, local venous infection, colonisation of the catheter tip, infusion failure, number of catheters per participant, overall duration of IV therapy, cost, mortality | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Random allocations were computer‐generated" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Random allocations were computer‐generated on a hand‐held device, at the point of each patient's entry, and thus were concealed to patients, clinical staff and research staff until this time" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Patients and clinical staff could not be blinded ........Research nurses were similarly not masked" Comment: neither participants nor clinical personnel were blinded but review authors do not believe this would introduce bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Evidence: "... laboratory staff were masked for rating of all microbiological end‐points, and a masked, independent medical rater diagnosed catheter‐related infections and all bloodstream infections" Comment: diagnosis of all other outcomes was unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | ITT analysis reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The protocol was available and all pre‐defined outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other known risks of bias |

| Methods | Study design: RCT Method of randomisation: computer‐generated Concealment of allocation: sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Number: 200. Clinically indicated: 105 participants. Routine replacement: 95 participants Age: clinically indicated 62.8 years (18.2); routine replacement 54.5 years (19.0) Sex (M/F): not stated Inclusion criteria: adult patients who could be treated at home for an acute illness and had a 20‐, 22‐, or 24‐gauge catheter inserted in an upper extremity Exclusion criteria: not stated | |

| Interventions | Clinically indicated: catheters were removed if there were signs of phlebitis, local infection, bacteraemia, infiltration or blockage Routine replacement: catheters were replaced every 72‐96 h | |

| Outcomes | Primary: phlebitis per participant and per 1000 device days (phlebitis was defined as a total score of ≥ 2 points from the following factors: pain (on a 10‐point scale, 1 = 1 point, and ≥ 2 = 2 points; redness (< 1 cm = 1 point, and ≥ 1 cm = 2 points); swelling (as for redness); and discharge (haemoserous ooze under dressing = 1 point, and haemoserous ooze requiring dressing change or purulence = 2 points) Also reported on: suspected IVD‐related bacteraemia and occlusion/blockage | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Comment: computer‐generated allocation (personal communication with trial author) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence:: "Randomization was concealed until treatment via sealed envelopes" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Comment: neither participants nor clinical personnel were blinded but review authors do not believe this would introduce bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Outcome assessment unable to be blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: participant flow chart provided. Results from all enrolled participants were reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: all planned outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other known risks of bias |

| Methods | Study design: multicentre, non‐inferiority, RCT Method of randomisation: computer‐generated Concealment of allocation: sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes | |

| Participants | Country: Brazil Number: 1319. Clinically indicated: 672 participants. Routine replacement: 647 participants Age: clinically indicated 59.7 (20.9); routine replacement 59.9 years (20.1) Sex (M/F): clinically indicated 339/333; routine replacement 318/329 Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

| |

| Interventions | Clinically indicated: catheters were removed according to clinical signs Routine replacement: catheters were replaced systematically every 96 h | |

| Outcomes | Primary: phlebitis Secondary: pain; infiltration; occlusion; accidental removal; extravasation | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "A computerized randomization program (random.org), a list prepared in blocks of six patients and stratified by ward and per hospital. Thus, each ward had its own randomization list, totaling 10 lists of randomization, six in Hospital A and four in Hospital B". (Personal communication) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "At the moment of the recruitment, that is, after the acceptance of the patient, the assistants have sent a message from a App (whatsApp) and I indicated the group" Comment: the person providing the allocation was unaware of the status of the potential participant and the person recruiting the participant was unaware of the allocation sequence |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Comment: neither participants nor clinical personnel were blinded but review authors do not believe this would introduce bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Unblinded study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No losses in either group. ITT analysis available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Expected outcomes reported. Consistent with ClinicalTrials.gov entry |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected |

| Methods | Study design: single‐centre RCT Method of randomisation: computer‐generated Concealment of allocation: allocation concealed until telephone contact made with an independent person | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Number: 206. Clinically indicated: 103 participants. Routine replacement: 103 participants Age: clinically indicated 60.2 years (16.2); routine replacement 63.1 years (17.3) Sex (M/F): clinically indicated 53/50; routine replacement 54/49 Inclusion criteria: ≥ 18 years of age, expected to have an IVD in situ, requiring IV therapy for ≥ 4 days, catheter inserted by a member of the IV team Exclusion criteria: immunosuppressed patients and those with an existing BSI | |

| Interventions | Clinically indicated: catheters removed if there were signs of phlebitis, local infection, bacteraemia, infiltration or blockage Routine replacement: catheters replaced every 3 days | |

| Outcomes | Primary: composite measure of any reason for an unplanned catheter removal Secondary: cost:

| |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Randomization was by computer generated random number list, stratified by oncology status" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Allocation was made by phoning a person who was independent of the recruitment process" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Clinical staff were subsequently aware of the treatment group" Comment: neither participants nor clinical personnel were blinded but reviewers do not believe this would introduce bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Evidence: "Research staff had no involvement in nominating the reason for catheter removal or in diagnosing phlebitis". Comment: diagnosis of all outcomes were unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: all recruited participants were accounted for in the results |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: protocol was available. All planned outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other known risks of bias |

| Methods | Study design: single‐centre RCT Method of randomisation: computer‐generated Concealment of allocation: telephone randomisation | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Number: 755. Clinically indicated: 379 participants. Routine replacement: 376 participants Age: clinically indicated 60.1 years (17.1); routine replacement 58.8 years (18.8) Sex (M/F): clinically indicated 248/131; routine replacement 233/143 Inclusion criteria: ≥ 18 years of age, expected to have a IVD in situ, requiring IV therapy for ≥ 4 days Exclusion criteria: immunosuppressed patients and those with an existing BSI | |

| Interventions | Clinically indicated: catheter removed if there were signs of phlebitis, local infection, bacteraemia, infiltration or blockage Routine replacement: catheter replaced every 3 days | |

| Outcomes | Primary: a composite measure of phlebitis (defined as ≥ 2 of the following: pain, erythema, purulence, infiltration, palpable venous cord) and infiltration Secondary:

Also reported: bacteraemia rate | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Block randomisation was by a computer generated random number list" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: ".... telephoned a contact who was independent of the recruitment process for allocation consignment" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "Allocation concealment avoided selection bias but clinical staff were subsequently aware of the treatment group" Comment: neither participants nor clinical personnel were blinded but review authors do not believe this would introduce bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Evidence: "Staff in the microbiological laboratory were blind to group assignment of catheters submitted for testing" Comment: all other outcomes were unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All recruited participants were accounted for in the results |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Protocol was available. All planned outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other known risks of bias |

| Methods | Study design: cluster‐RCT of 20 wards in a tertiary referral hospital in China Method of randomisation: coin toss Concealment of allocation: coin toss | |

| Participants | Country: China Number: clinically indicated: 553 patients. Routine replacement: 645 patients. Age: clinically indicated 58.7 years (39.7); routine replacement 56.2 years (27.1) Sex (M/F): clinically indicated 325/208; routine replacement 335/310 Inclusion criteria: adult patients > 18 years of age who received catheter infusion; patients who were expected to use the indwelling catheter for ≥ 3 days; patients who used PIVCs for the first time during hospitalisation; and patients who agreed to participate in this study Exclusion criteria: patients with BSI or under immunosuppressive therapy; patients receiving parenteral nutrition infusion through PIVC; patients with indwelling catheters for > 72 h at study entry; and severe infection or hepatocellular failure and renal failure | |

| Interventions | Intervention: PIVCs were removed/replaced if there was a clinical indication to do so Control: PIVCs were replaced every 3 days in the control group (the routine‐replacement group) following hospital policy. The duration of '3 days' refers to the approximate 72 h (range: 48‐96 h) from the time of insertion to removal of a catheter. They were also removed/replaced if there was a clinical indication to do so | |

| Outcomes | Primary: incidence of phlebitis: defined as when ≥ 2 of the following signs occurred at the catheter access site: redness, swelling, fever, pain, or palpable cord‐like veins Secondary: fluid infiltration (when the infused non‐blister drug leaked into the surrounding tissue from the normal vascular access, causing tissue swelling around the catheter access site); catheter occlusion (when the drug fluid could not flow into the body or the fluid could not be withdrawn); accidental catheter removal; CRBSI (diagnosed when signs of infection (e.g. fever, chills, and hypotension), positive results, and the same type of bacteria were found in bacterial cultures of both peripheral venous blood and the PIVC tip, and no other apparent source of BSI other than the IV catheter was observed (including BSI within 48 hours of catheter indwelling); local venous infection, i.e. purulent discharge or bloodstream‐related infection with no evidence at vein segment; and indwelling time | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "These 20 internal medicine and surgery ward patients were randomly assigned by a research assistant via a coin toss into 2 groups" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Evidence: "These 20 internal medicine and surgery ward patients were randomly assigned by a research assistant via a coin toss into 2 groups". Comment: allocation remains concealed until the coin is tossed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Evidence for participants: "All of the participating patients were not blinded in the groups" Evidence for personnel: "Because of the nature of the intervention in this study, the chief nurse in charge of the research wards and the clinical nurses were not blinded to the random grouping" Comment: neither participants nor clinical personnel were blinded but review authors do not believe this would introduce bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Evidence: "The peripheral blood samples and the catheter tips of patients with suspected CRBSI were sent for laboratory examination, and the laboratory examiners were blinded" Comment: blinding not possible for other outcomes and there was no laboratory confirmed diagnosis |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: complete data reporting for all outcomes: after 235 people, who were potentially eligible by belonging to a ward that was randomised, were excluded. 1198 participants were included for the final analysis (flow chart included) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: expected outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: this was a cluster trial but analysed by individual not cluster |

BSI: blood stream infection; CRBSI: catheter‐related blood stream infection; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; IV: intravenous; IVD: peripheral intravenous device; PIVC: peripheral intravenous catheter; PVT: peripheral vein infusion thrombophlebitis; RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Not a RCT | |

| Involved central, not peripheral lines | |

| Involved pulmonary artery or arterial catheters, not peripheral catheters | |

| End point was lymphangitis | |

| Participants were receiving parenteral nutrition | |

| Participants were receiving parenteral nutrition | |

| Involved central, not peripheral lines | |

| Compared the use of a single intraoperative and postoperative catheters with 2 catheters, 1 used intraoperatively and a separate catheter for postoperative use | |

| Involved central, not peripheral lines |

RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Methods | RCT 1:1 |

| Participants | 113 neonates born at ≥ 32 weeks' gestation |

| Interventions | PIVC replaced every 72‐96 h or replaced when clinically indicated |

| Outcomes | Primary: extravasation Secondary: phlebitis; leakage; accidental dislodgement |

| Notes | No response to request for additional data as yet |

PIVC: peripheral intravenous catheter; RCT: randomised controlled trial

Data and analyses

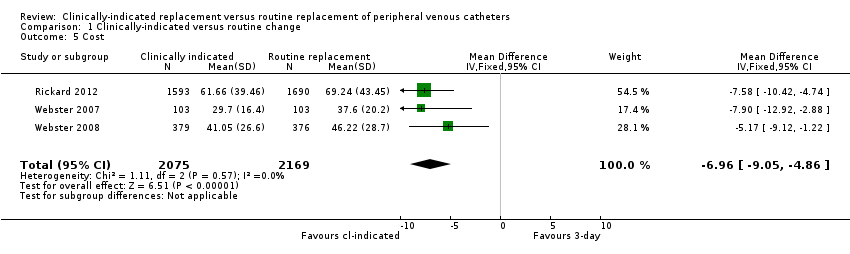

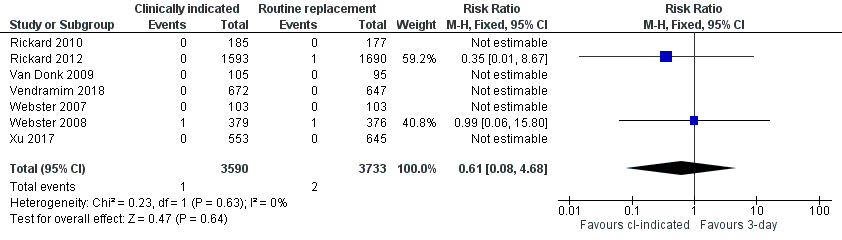

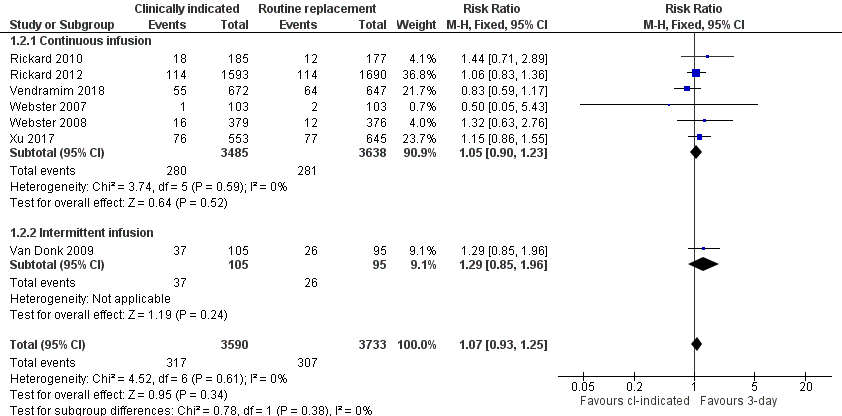

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter‐related blood stream infection Show forest plot | 7 | 7323 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.08, 4.68] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related blood stream infection. | ||||

| 2 Phlebitis Show forest plot | 7 | 7323 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.93, 1.25] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 2 Phlebitis. | ||||

| 2.1 Continuous infusion | 6 | 7123 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.90, 1.23] |

| 2.2 Intermittent infusion | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.85, 1.96] |

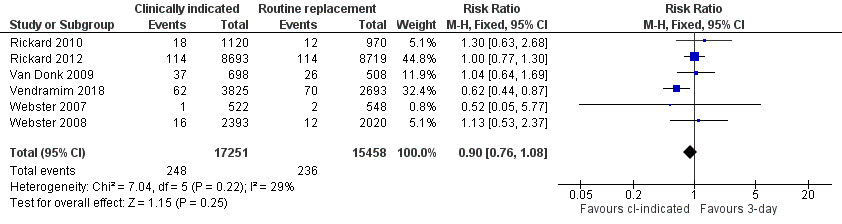

| 3 Phlebitis per device days Show forest plot | 6 | 32709 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.76, 1.08] |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 3 Phlebitis per device days. | ||||

| 4 All‐cause blood stream infection Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 4 All‐cause blood stream infection. | ||||

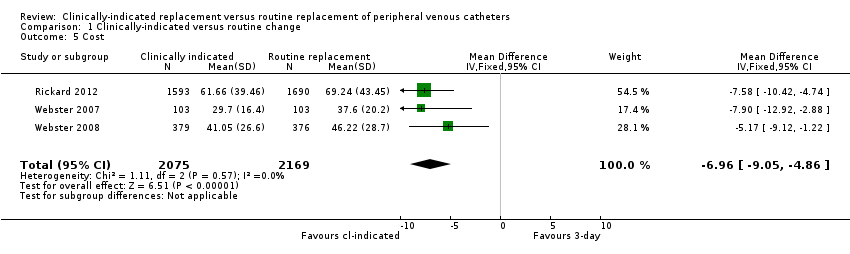

| 5 Cost Show forest plot | 3 | 4244 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.96 [‐9.05, ‐4.86] |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 5 Cost. | ||||

| 6 Infiltration Show forest plot | 6 | 7123 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [1.06, 1.26] |

| Analysis 1.6  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 6 Infiltration. | ||||

| 7 Catheter blockage Show forest plot | 7 | 7323 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [1.02, 1.27] |

| Analysis 1.7  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 7 Catheter blockage. | ||||

| 8 Local infection Show forest plot | 4 | 4606 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.96 [0.24, 102.98] |

| Analysis 1.8  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 8 Local infection. | ||||

| 9 Mortality Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 1.9  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 9 Mortality. | ||||

| 10 Pain during infusion Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| Analysis 1.10  Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 10 Pain during infusion. | ||||

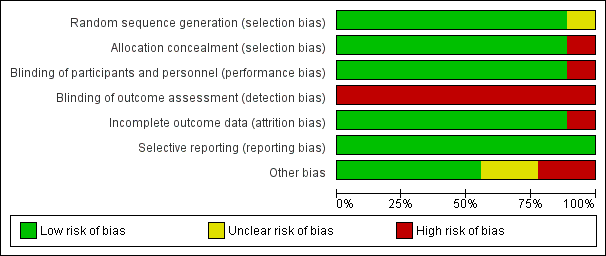

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Forest plot of comparison 1, clinically indicated versus routine change, outcome: 1.1 Catheter‐related bloodstream infection

Forest plot of comparison 1, clinically indicated versus routine change, outcome: 1.2 Phlebitis

Forest plot of comparison 1 clinically indicated versus routine change, outcome: 1.3 Phlebitis per device days

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 1 Catheter‐related blood stream infection.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 2 Phlebitis.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 3 Phlebitis per device days.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 4 All‐cause blood stream infection.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 5 Cost.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 6 Infiltration.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 7 Catheter blockage.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 8 Local infection.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 9 Mortality.

Comparison 1 Clinically‐indicated versus routine change, Outcome 10 Pain during infusion.

| Effects of clinically indicated replacement compared to routine change of peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVC) | ||||||

| Patient or population: any patient requiring a PIVC expected to remain in‐situ for at least 3 days | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Certainty of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with routine change | Risk with clinically indicated | |||||

| Catheter‐related blood stream infection (during hospitalisation) | Study population | RR 0.61 | 7323 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | There is no clear difference in the incidence of catheter‐related blood stream infection. The wide CI includes the possibility of both increased and decreased infection. The true effect could range from a 92% reduction to a 4.68 times increase in the clinically indicated group. | |

| 1 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 | |||||

| Thrombophlebitis (during hospitalisation) | Study population | RR 1.07 | 7323 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | There is no clear difference in the incidence of phlebitis between the clinically indicated and routine‐change groups. Although the outcome assessment for laboratory‐based outcomes, such as blood stream infection was blinded; only 2 trials reported these outcomes. Most outcomes were assessed by clinicians or researchers who were aware of the group to which the participant belonged. | |

| 82 per 1000 | 88 per 1000 | |||||

| Thrombophlebitis (per device days) (during hospitalisation) | Study population | RR 0.90 | 32,709 device days | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | There is no clear difference in the incidence of phlebitis when assessed correctly (incidence/1000 device days) between the clinically indicated and routine‐change groups. The true effect could range from a 24% reduction to an 8% increase in the clinically indicated group. | |

| 15 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 | |||||

| All‐cause blood stream infection (during hospitalisation) | Study population | RR 0.47 | 3283 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | There is no clear difference in all‐cause blood stream infections between the clinically indicated and routine‐change groups. Although a large trial, only Rickard 2012 assessed this outcome. The assessor was blinded for this outcome. | |

| 5 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 | |||||

| Cost (during hospitalisation) | The mean cost in the control group was AUD 51.02 | The mean cost in the intervention group was AUD 44.14 MD | ‐ | 4244 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Clinically indicated peripheral catheter removal probably reduces the cost of catheter‐related care by approximately AUD 7.00 |

| Infiltration (during hospitalisation) | Study population | RR 1.16 | 7123 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Routine replacement probably leads to a slightly lower incidence of infiltration compared to a clinically indicated change. | |

| 205 per 1000 | 238 per 1000 | |||||

| Catheter blockage (during hospitalisation) | Study population | RR 1.14 | 7323 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Routine replacement probably leads to a slightly lower incidence of blockage compared to a clinically indicated change. | |

| 139 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1 Downgraded two levels for very serious inconsistency. | ||||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Catheter‐related blood stream infection Show forest plot | 7 | 7323 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.08, 4.68] |

| 2 Phlebitis Show forest plot | 7 | 7323 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.93, 1.25] |

| 2.1 Continuous infusion | 6 | 7123 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.90, 1.23] |

| 2.2 Intermittent infusion | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.85, 1.96] |

| 3 Phlebitis per device days Show forest plot | 6 | 32709 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.76, 1.08] |

| 4 All‐cause blood stream infection Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Cost Show forest plot | 3 | 4244 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.96 [‐9.05, ‐4.86] |

| 6 Infiltration Show forest plot | 6 | 7123 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [1.06, 1.26] |

| 7 Catheter blockage Show forest plot | 7 | 7323 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [1.02, 1.27] |

| 8 Local infection Show forest plot | 4 | 4606 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.96 [0.24, 102.98] |

| 9 Mortality Show forest plot | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10 Pain during infusion Show forest plot | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |