Musiktherapie bei Depression

References

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to studies awaiting assessment

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Methods | Study design: randomised controlled trial, pre‐test post‐test control group design Aim of study: to determine the effectiveness of improvisational music therapy in relieving symptoms of depression among adolescents and adults with substance abuse Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: music therapy and standard treatment Control arm: standard treatment Consumer involvement: evaluating depression, using patient‐reported BDI Informed consent: yes; opportunity to provide informed consent Ethical approval: yes; approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB‐10739) was obtained Power calculation: unclear; the Statistical Program for Power Analysis and Sample Size was used to compute effect size and power | |

| Participants | Description: patients Geographical location: Mérida, Venezuela, South America Methods of recruitment of participants: The researcher requested referrals at the beginning of each 3‐month treatment cycle at the facility, when new patients were admitted. Each set of newly admitted patients who met inclusion criteria was randomly assigned to the experimental or control condition. Setting: foundation; Fundación José Felix Ribas (FJFR) Principal health problem: substance abuse Inclusion: (1) some kind of addiction problem, including addiction or abuse of psychotropic and pharmacological substances such as alcohol; (2) recently admitted to the treatment program for substance abuse at the centre; and (3) scores on BDI or HRSD indicating that they were significantly depressed (e.g. > 10 on the BDI, > 7 on the HRSD) Exclusion: (1) unable to communicate (aphasia); (2) diagnosis of mental retardation and incapable of symbolic thinking; (3) hearing losses that impaired ability to hear music or the spoken word; and (4) not receiving medication for depression Severity of depression: mild to severe Number of prior depressive episodes: not reported Comorbidity: depression Age, range, mean (standard deviation): range 16 to 60 years of age. Mean not reported Sex: male Sociodemographics: not reported Ethnicity: not reported Exclusion important groups: no Total numbers included in this trial: N = 24 Numbers included in music therapy: n = 12 Numbers included in control group: n = 12 | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm Intervention: music therapy Excluded intervention: not reported Name of intervention: Artistic Music Therapy (MAR) (see also Albornoz 2016) Aims and rationale: not reported Method: active music therapy What was done:(materials) simple percussion, other materials not reported;(procedures) free music improvisation, free discussion, explorations in other artistic media (e.g. movement, poetry, psychodrama) and public performance;(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face;(co‐interventions) treatment as usual;(medication) not reported Location: Fundación José Felix Ribas (FJFR), located in Mérida, Venezuela. Specific location for music therapy not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): MAR sessions unfold from moment to moment according to participants’ responses and needs. Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: once weekly Duration of session: 2 hours Duration of treatment: 3 months Delivered number of sessions: 12 Individual or group: group Who delivered intervention: researcher, therapist Therapist training: Doctor of Philosophy in Music Therapy, Bachelor of Music, Master of Music Therapy, Technicature in Rehabilitation Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: Technicature in Rehabilitation Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: not reported Control arm Intervention: treatment as usual Excluded intervention: music therapy Name of intervention: treatment as usual Aims and rationale: not reported Type of therapy: individual psychotherapy, group psychotherapy (emotional and cognitive‐behavioural groups), family and couple groups, and morning groups conducted by advanced patients, pharmacotherapy, recreational, social and sport activities, special activities, general medical care, and social work assistance What was done:(materials) not reported;(procedures) not reported;(mode of delivery) not reported;(co‐interventions) not reported;(medication) not reported Location: Fundación José Felix Ribas (FJFR), located in Mérida, Venezuela. Specific location not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: not reported Duration of session: not reported Duration of treatment: 3 months Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: not reported Who delivered intervention: not reported Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Clinician‐rated depression: HRSD Patient‐reported depression: BDI | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: not reported Notable conflicts: not reported Other: none Key conclusions: (1) Individuals with substance abuse showed significant improvement in clinician‐reported depression (HRSD) as a result of improvisation therapy, but did not show significant improvement in patient‐reported depression (BDI), when compared with individuals in regular treatment programme alone. (2) Psychologists apparently perceived greater improvement in depression among participants than participants perceived in themselves. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

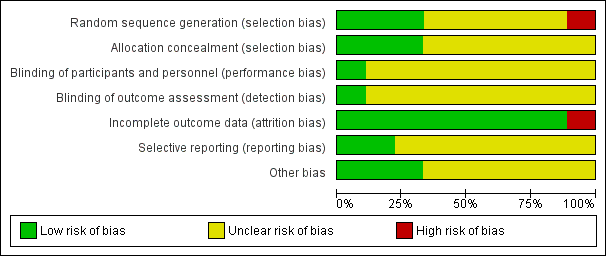

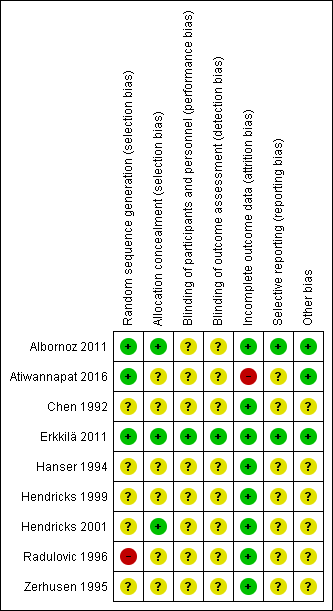

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process. Quote: “Each set of newly admitted patients who met inclusion criteria was randomly assigned to the experimental or control condition. A statistician used the Excel1 program to generate random number lists in blocks; each list contained the numbers of subjects to be assigned to control and experimental groups.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment. Quote: “Sequentially numbered envelopes were created to ensure allocation concealment." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Personnel were blinded. For participants, blinding was not possible. Quote: "The psychologist provided an evaluation of the participant’s level of depression on the HRSD. The psychologist did not know which participants were in the experimental and control groups. Moreover, the psychologist did not treat any of the participants." Quote: "Dependent variables used in this study were: (1) self‐rated depression scores on the BDI, and (2) psychologist‐rated depression scores on the HRSD." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Outcome assessment for HRSD was blinded. For BDI, blinded outcome assessment was not possible. Quote: "The researcher who administered the BDI had no access to medical charts and the psychologist did not know which participants were in the experimental and control group." Quote: "Dependent variables used in this study were: (1) self‐rated depression scores on the BDI, and (2) psychologist‐rated depression scores on the HRSD." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No outcome data were missing. Quote: See Results Table 2. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | An earlier published dissertation was available, and all outcomes were reported as planned. Quote: "The researcher administered the BDI as a pre‐test to all participants referred by the psychologist at the facility and did not have access to medical charts. In addition, the psychologist provided an evaluation of the participant’s level of depression on the HRSD." (See Albornoz 2009 and Table 1 in study report.) |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

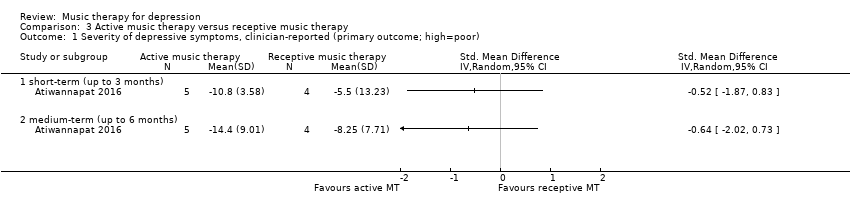

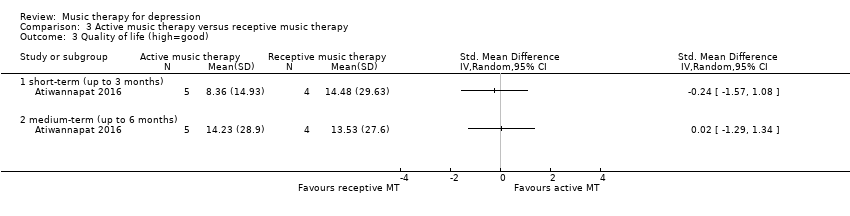

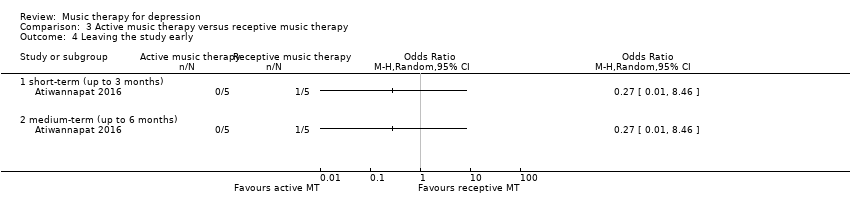

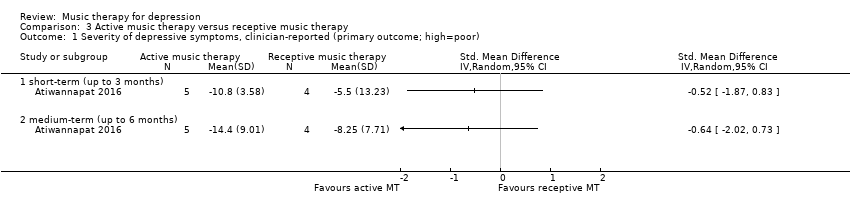

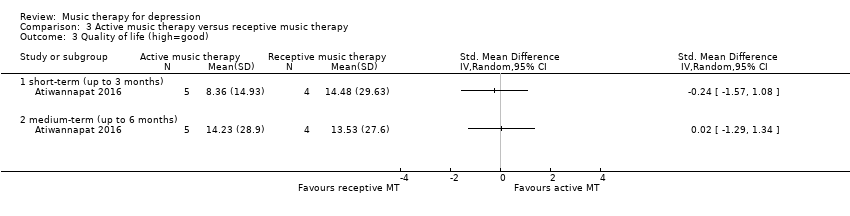

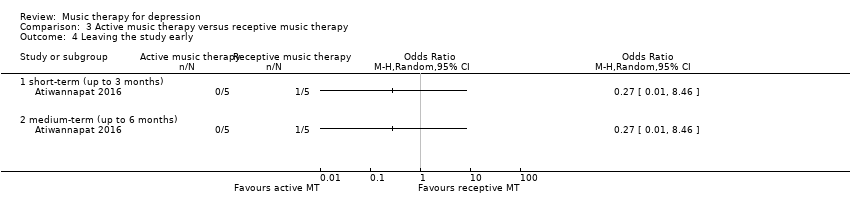

| Methods | Study design: single‐blinded randomised controlled trial Aim of study: to compare the effectiveness of music therapy (active and receptive groups) and group counselling in MDD Number of arms: 3 Experimental arm: music therapy (active) Control arm 1: music therapy (receptive) Control arm 2: counselling Consumer involvement: evaluating depression and quality of life, using patient‐reported TDI, SF‐36 Thai Informed consent: yes; method not reported Ethical approval: yes; study was approved by the Institution Committee on Human Rights Related to Research Involving Human Subjects Power calculation: not reported | |

| Participants | Description: outpatients Geographical location: Asia, Thailand, Bangkok Methods of recruitment of participants: not reported Setting: hospital Principal health problem: major depressive disorder (MDD) Inclusion: ICD‐10 diagnosis of MDD; score ≥ 7 on the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) Thai version required. Eligibility did not include medication status and music skills. Exclusion: severe depression with repeated suicidal behaviour/psychotic symptoms or need for hospitalisation, substance abuse/dependence, hearing or communication problems, and treatment with psychotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy Severity of depression: mild to severe depression Number of prior depressive episodes: duration of depression in years, mean (SD) 9.48 (12.56) active music therapy; 8.95 (11.59) receptive music therapy; 8.77 (13.09) counselling Comorbidity: medical comorbidity Age, range, mean (standard deviation): 18 to 65 years; mean (SD) 41.6 (11.15) active music therapy; 54.4 (6.73) receptive music therapy; 55.25 (10.21) counselling Sex: male and female Sociodemographics active music therapy: married (n= 1); employed (n = 5); musical background (patient‐reported): sings (n = 1), plays an instrument (n = 1), both (n= 1) Sociodemographics receptive music therapy (n= 3); employed (n = 2); musical background (patient‐reported): sings (n= 2), plays an instrument (n= 0), both (n= 0) Sociodemographics counselling: married (n= 2); employed (n= 2); musical background (patient‐reported): sings (n= 1), plays an instrument (n= 0), both (n = 0) Ethnicity: not reported Exclusion important groups: not reported Total numbers included in this trial: N = 14 Numbers included in active music therapy: n = 5 Numbers included in receptive music therapy: n = 5 Numbers included in control group: n = 4 | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm Intervention: active music therapy Excluded intervention: treatment with psychotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: "To improve depressive symptoms and quality of life. CBT was used as the theoretical framework, but therapists did not limit themselves. To encourage positive ideas and behaviour, increase relaxation, support positive engagement between the group members and also between the therapists and the group members, provide outlet or expression, and encourage positive coping skills and socialisation" (info e‐mail)." "The music therapists will utilize ISO principle which is a music therapy technique that uses the music that, first, matches the mood/state of the subjects, then, slowly alters the music speed and style to change the mood/state of the subjects." (info unpublished MT protocol) Method: active music therapy What was done:(materials) voice, percussion, such as maracas, egg shakers, and rhythm sticks;(procedures) each session contained 3 phases: opening (10 to 15 minutes), 1 or 2 main interventions (35 to 45 minutes), and closing (5 to 10 minutes). All sessions were facilitated by a board‐certified (MT‐BC) music therapist and a music therapy assistant. Sessions began with group singing. Main interventions were (1) Instrument choir playing, including anklung, tone bars, and hand bells; (2) song writing and group performance; and (3) improvisation using percussion such as maracas, egg shakers, and rhythm sticks. Sessions ended with group singing and instrument playing;(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face;(co‐interventions) treatment as usual = counselling and medication, but not psychotherapy and not electroconvulsive therapy;(medication) SSRIs Location: Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported. "The music therapy approach they used changed occasionally according to moment‐to‐moment needs of the groups. The order of the interventions was sometimes changed according to needs of the groups (info e‐mail)." Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: weekly Duration of session: 1 hour Duration of treatment: 12 sessions Delivered number of sessions: Average number of sessions per participant was 8 (SD 2.6), range 5 to 12. Individual or group: group Who delivered intervention: board‐certified (MT‐BC) music therapist (PP) and music therapy assistant Therapist training: Bachelor of Music Therapy Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: not reported Control arm Intervention: receptive music therapy (control arm 2: counselling; all info reported between brackets) Excluded intervention: treatment with psychotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (treatment with psychotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy) Name of intervention: not reported (not reported) Aims and rationale: to improve depressive symptoms and quality of life. "The music therapists will utilize ISO principle which is a music therapy technique that uses the music that, first, matches the mood/state of the subjects, then, slowly alters the music speed and style to change the mood/state of the subjects (info MT protocol)." (to improve depressive symptoms and quality of life, problem‐solving and coping skills) Method/Type of therapy: receptive music therapy (counselling and medication) What was done:(materials) for both receptive group and counselling group not reported;(procedures) each session contained 3 phases: opening (10 to 15 minutes), 1 or 2 main interventions (35 to 45 minutes), and closing (5 to 10 minutes). All sessions were facilitated by a board‐certified (MT‐BC) music therapist and a music therapy assistant. Sessions began with music listening. Main interventions were (1) lyric analysis including sharing thoughts and comments, (2) song writing, facilitated by music therapist, but participants selected words of their choice; and (3) drawing while listening to the music. Sessions ended with music and relaxation. Active music‐making behaviours were not actively reinforced (group interventions, focus on problem‐solving, and improved coping skills); (mode of delivery) face‐to‐face (face‐to‐face);(co‐interventions) treatment as usual, medication, but not psychotherapy and not electroconvulsive therapy (medication, but not psychotherapy and not electroconvulsive therapy) Location: Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University) Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported (not reported) Modification intervention: not reported (not reported) Quality of delivery: not reported (not reported) Intensity of sessions: weekly (weekly) Duration of session: 1 hour (1 hour) Duration of treatment: 12 sessions (12 sessions) Delivered number of sessions: 7.6 (SD 4.0, range 2 to 11); (6.8 (SD 5.6, range 1 to 12)). When dropouts were excluded, average number of sessions in receptive and control groups was increased to 9 (SD 2.8, range 5 to 11); (11.5 (SD 0.7, range 11 to 12)) Individual or group: group (group) Who delivered intervention: board‐certified (MT‐BC) music therapist and music therapy assistant (senior psychiatry resident) Therapist training: not reported (not reported) Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported (not reported) Tailoring (how, why, when, what): not reported (not reported) Modification intervention: not reported (not reported) Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: not reported (not reported) | |

| Outcomes | Clinician‐rated depression: MADRS Thai Patient‐reported depression: TDI Quality of life: Thai SF‐36 | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: This study was supported by a Research Grant from the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University Number RF 57011. Notable conflicts: Trial authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. Other: none Key conclusions: Group music therapy is an interesting adjunctive treatment for MDD. The receptive group may reach peak therapeutic effect faster, but the active group may have higher peak effect. Further trials evaluating these non‐invasive interventions in MDD are required. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process. Quote: “Participants were randomly assigned to active group, receptive group, and counselling group using drawing lots 1:1:1 randomization.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. The method of concealment was not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Personnel were blinded. For participants, blinding was not possible. Quote: “One well‐trained psychiatric nurse who evaluated patients’ outcomes, including MADRS rating, was blinded to assigned interventions.” Quote: “The secondary outcomes were the change from baseline in self‐rated depression score ... and quality of life..." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Primary outcome was blinded. For patient‐reported secondary outcomes, blinding of outcome assessment was not possible. Quote: “One well‐trained psychiatric nurse who evaluated patients’ outcomes, including MADRS rating, was blinded to assigned interventions. The primary outcome was the change from baseline in MADRS Thai depression total score.” |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | The proportion of and reason for data missing from one of the control arms were large enough to have a clinically relevant effect because of the small group. Quote: "There was no dropout in the active music therapy groups. One (20%) patient in the receptive group dropped out... due to unknown reason. Two patients (50%) dropped out in the control group due to lack of motivation." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A protocol for the study was not available, and all expected outcomes were identified and reported as planned in the methods section. Quote: “The efficacy analyses used an intention‐to‐treat group with all randomly assigned patients who had at least one post‐baseline assessment” (and Table 1). |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| Methods | Study design: randomised controlled trial Aim of study: to assess the effect of music therapy for geriatric depression Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: music therapy and tricyclic antidepressants Control arm: tricyclic antidepressants Consumer involvement: Only clinician‐rated outcome measures were used. Informed consent: not reported Ethical approval: not reported Power calculation: not reported | |

| Participants | Description: patients Geographical location: Asia, Beijing Methods of recruitment of participants: not reported Setting: hospital Principal health problem: geriatric depression; some experienced episodes of bipolar disorder Diagnostic criteria for inclusion: geriatric depression. Diagnostic criteria for exclusion: not reported Severity of depression: > 17 on the HAM‐D Number of prior depressive episodes: not reported Comorbidity: unclear whether anxiety was a comorbidity Age, range, mean (standard deviation): experimental group: 60 to 77, mean 63.91 (SD 4.85); control group: 60 to 79, mean 64.12 (SD 4.75) Sex: male and female Sociodemographics intervention group: Treatment periods range from 3 months to 3 years; high school education and beyond (n = 15); junior high school and lower (n = 19); interested in music (n = 14); not interested in music (n = 20) Sociodemographics control group: Treatment periods range from 2 months to 3 years; high school education and beyond (n = 14); junior high school and lower (n = 20); interested in music (n = 12); not interested in music (n = 22) Ethnicity: Chinese. Exclusion important groups: no Total numbers included in this trial: N = 68 Numbers included in music therapy: n = 34 Numbers included in control group: n = 34 | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm Intervention: music therapy Excluded intervention: no interventions Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: to decrease depressive symptoms Method: active music therapy What was done:(materials) digital piano, accordion, guitar, violin, erhu, several types of percussion instruments; enough material to ensure that 1 was available for every procedure; (procedures) the doctor and the music therapist chose lyrical, smooth, and livelily music. The choice of music was based on the participant's situation. The music therapist also wrote 9 songs based on participant preferences. These songs had been evaluated by composers and psychiatrists, who considered them suitable for use in the treatment of geriatric depression, easy to learn, and having a clear rhythm. Apart from the musical performance, the music therapist wrote a number of songs in call and response style, in which a question‐answer pattern in the music was used to ask participants whether they had slept well and what they had on their mind; these questions and answers allowed for an emotional connection with participants and gave rise to emotional resonance, which increased emotional response and interest in life;(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face; (co‐interventions) standard care, e.g. medication and hospitalisation; (medication) tricyclic antidepressants Location: music therapy treatment room Tailoring (how, when, why, what): The music therapist wrote 9 songs based on participant preferences. Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: 6 times a week Duration of session: 1 hour Duration of treatment: 8 weeks Delivered number of sessions: 48 sessions Individual or group: group Who delivered intervention: music therapist and a doctor Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: not reported Control arm Intervention: tricyclic antidepressants Excluded intervention: music therapy Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: to decrease depression Type of TAU: antidepressants What was done:(materials) tricyclic antidepressants;(procedures) both treatment group and control group underwent treatment with the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline, starting with 25 mg/d, which was increased to 50 mg/d within 3 days; (mode of delivery) face‐to‐face; (co‐interventions) not reported Location: not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): After 2 weeks, a clinical physician decided on increasing or decreasing the amount of medication based on the participant's condition (not based on the assessment score on the scale). Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: not reported Duration of session: not reported Duration of treatment: not reported Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: not reported Who delivered intervention: a clinical physician Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to TAU: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Clinician‐rated depression: HAM‐D Anxiety: HAM‐A | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: not reported Notable conflicts: not reported Other: missing SD for clinician‐rated depression and anxiety Key conclusions: (1) Results of this report show that under equivalent conditions, participants with geriatric depression treated with music therapy showed quicker alleviation of clinical symptoms, and the dose of medication was lower, with lighter side effects. (2) Data show no significant differences between results of music therapy in terms of individual symptoms, and no relation with whether or not participants had a musical hobby. (3) Easy‐listening, smooth, and lively music was accepted more easily by participants with geriatric depression and yielded better treatment results. (4) The rate of bedriddenness decreased over the course of treatment. The atmosphere in the patient area was lively, and worry and fear among older adults with regard to hospitalisation were eliminated. Music therapy is a way for participant and the therapist to communicate emotions, mobilise participant co‐operation in treatment, and decrease the difficulty of nursing those with geriatric depression. This benefited management of the treatment area. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information about the sequence generation process was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. Method of randomisation was not reported. Quote: "68 hospitalised patients diagnosed with geriatric depression have been randomly divided into a music‐therapy treatment group and a control (observation) group." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. Method of concealment was not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Study did not address this outcome. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No outcome data were missing. Quote: "When assessing clinical treatment results by the end of week 8, 32 cases of the treatment group showed alleviation (94.7%), while 2 cases showed either improvement or no change, whereas in the control group, 23 cases showed alleviation (68.0%) and 11 cases showed either improvement or no change." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A protocol for the study was not available, and all expected outcomes were identified and reported as planned in the methods section. Quote: "The patients in both groups were assessed using the HAMD depression and anxiety scale" (and Table 1). |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Risk of bias may be present, but information was insufficient for assessment of whether an important risk of bias existed. |

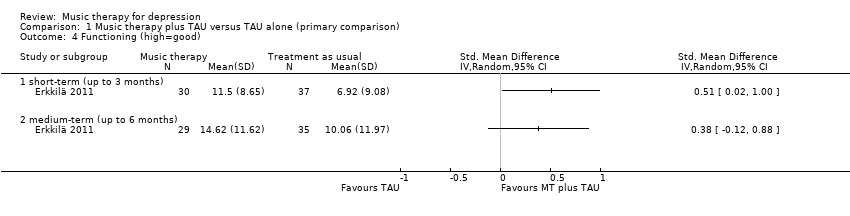

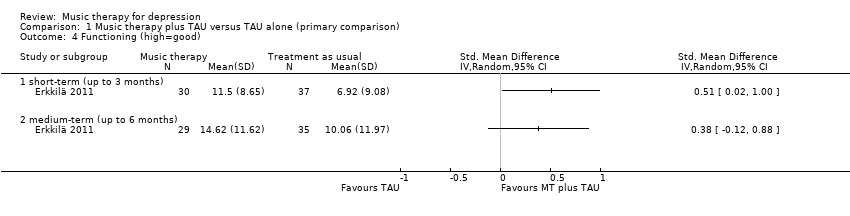

| Methods | Study design: randomised controlled trial Aim of study: to assess the effects of music therapy on depression for working‐age adults and TAU vs the effects of TAU Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: music therapy and TAU Control arm: TAU Consumer involvement: evaluating anxiety, quality of life, alexithymia, and using patient‐reported HADS‐A, RAND‐36, TAS‐20 Informed consent: yes; all participants gave signed informed consent to the study Ethical approval: yes; the ethical board of the Central Finland Health Care District gave its approval for the study on 24 October 2007 Power calculation: yes; details in the study protocol | |

| Participants | Description: patients and people in the community Geographical location: Europe, Finland, Jyväskylä Methods of recruitment of participants: Clinicians identified potential participants among their patients and gave them information about the study; newspaper advertisements were launched to boost recruitment. Setting: music therapy clinic for Research and Training, University of Jyväskylä; also, Central Finland Health Care District’s psychiatric health centres and the psychiatric polyclinics of Jyväskylä City Principal health problem: depression Inclusion: clients who had a primary diagnosis of depression, F32 or F33, according to IDS‐10 classification Exclusion: clients who had a history of repeated suicidal behaviour or psychosis, acute and severe substance misuse, severity of depression that prevented them from participating in the measurements or engaging in verbal conversation, or had insufficient knowledge of the Finnish language Severity of depression: mild to severe Number of prior depressive episodes: not reported Comorbidity: anxiety Age, range, mean (standard deviation): 18 to 50 years, mean in music therapy group 35.8 (9.0), mean in control group 35.5 (10.5) Sex: female and male Sociodemographics intervention group: sing (n = 11); play an instrument (n = 14); have musical training (n = 7); patient‐reported musician/singer (n = 9) Sociodemographics control group: sing (n = 12); play an instrument (n = 13); have musical training (n = 6); patient‐reported musician/singer (n = 8) Ethnicity: not reported Exclusion important groups: no Total numbers included in this trial: N = 79 Numbers included in music therapy: n = 33 Numbers included in control group: n = 46 | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm Intervention: music therapy Excluded intervention: not reported Name of intervention: Individual Psychodynamic Music Therapy (IPMT) (Erkkilä 2008; Erkkilä 2014) Aims and rationale: The basic principle of the intervention is to encourage and engage clients in expressive musical interaction, based on psychodynamic principles. Method: active music therapy (Psychodynamic Improvisational Music Therapy) What was done:(materials) a selection of instruments where available for both music therapist and client, including a mallet instrument, a percussion instrument, and an acoustic djembe drum;(procedures) free improvisation in music therapy. Music therapists were trained and supervised before and during intervention using video;(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face;(co‐interventions) TAU, e.g. psychotherapy, psychiatric counselling when needed, and/or antidepressant); (medication) SSRI, SNRI Location: music therapy clinic for Research and Training at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: The intervention was well delivered. For treatment fidelity, therapists participated in extensive training before the study, lasting for 15 months. During the study, video recordings of clinical sessions were used frequently in supervision, for monitoring both adherence to the method and competence in its application. Intensity of sessions: bi‐weekly Duration of session: 1 hour Duration of treatment: 20 sessions Delivered number of sessions: 18 to 20 Individual or group: individual Who delivered intervention: 10 qualified music therapists (3 male, 7 female); 15 months prior training and 2 monthly group sessions throughout the study Therapist training: professional training in music therapy Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: supervision (group‐based, 2 monthly sessions throughout the study, extensive training before the study, lasting for 15 months) Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: Video recordings of clinical sessions were used in supervision. Control arm Intervention: TAU Excluded intervention: music therapy Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: not reported Type of therapy: psychotherapy, psychiatric counselling when needed, antidepressant (SSRI, SNRI) What was done:(materials) not reported;(procedures) 5 to 6 individual sessions of psychotherapy were conducted by nurses specially trained in depression;(mode of delivery) not reported;(co‐interventions) antidepressants, including SSRIs and SNRIs, psychiatric counselling when needed (appointments for advice follow‐up and support when needed);(medication) antidepressants, including SSRIs and SNRIs Location: not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: not reported Duration of session: not reported Duration of treatment: 5 to 6 sessions, number of psychiatric counselling sessions not reported, not reported for medication use Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: individual Who delivered intervention: nurses specially trained in psychotherapy for depression; no information reported on medication and delivery of psychiatric counselling Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: trained in depression Tailoring (how, why, when, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Clinician‐rated depression: MADRS Adverse events: qualitative data report Anxiety: HADS‐A Functioning: GAF Quality of life: RAND‐36 Alexithymia: TAS‐20 | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: The NEST programme of European Commission, and programme for Centres of Excellence in research, Academy of Finland Notable conflicts: none Other: none Key conclusions: Individual music therapy added to standard care is effective for depression, anxiety, and functioning among working‐age people with depression. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process. Quote: "An independent person at Uni Health, Bergen, Norway, generated the randomisation list using a spreadsheet software program." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment. Quote: "An independent person kept each participant’s allocation concealed from the investigators until a decision about inclusion was made. Once all baseline data had been collected and informed consent obtained, the investigators used email to receive the allocation for the respective participant." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Personnel were blinded and participants were not, but the review authors judge that the outcome was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. Quote: "One masked clinical expert (I.P.), with training in psychiatric nursing and long experience in psychiatry, conducted all the psychiatric assessments." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Depression and anxiety were blinded. Quote: "One masked clinical expert (I.P.), with training in psychiatric nursing and long experience in psychiatry, conducted all the psychiatric assessments." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Missing data have been imputed via appropriate methods. Quote: "All analyses were intention‐to‐treat. For dichotomous outcomes, this meant that we assumed the negative outcome when the information was missing. For continuous outcomes, intention‐to‐treat meant that we retained data from all participants for whom the information was available. Full intention‐to‐treat including all randomised participants is not possible for continuous outcomes. Multiple imputations is not recommended when data are missing on dependent but not on independent variables, as it would only serve to increase standard errors. As a sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome, we assumed no change for those where the outcome was unobserved. Distributions of scores and change scores were examined graphically, and if unusual outliers were found they were excluded in a sensitivity analysis." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | A protocol for the study was available, and all expected outcomes were identified and reported as planned. Quote: "Symptoms of depression will be measured with the ... MADRS... Anxiety will be evaluated by the ...HADS... General functioning will be measured using ...GAF ... Quality of life will be evaluated by the RAND‐36...Alexithymia will be evaluated with the TAS‐20, ..." (Erkkilä 2008 and Table 2 in study report) |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| Methods | Study design: randomised controlled trial Aim of study: This study examined the effect of a music listening, stress reduction strategy, offered through home visits with a therapist as opposed to self‐administered techniques with moderate and indirect therapist contact. It compared these conditions with a no‐contact, wait‐list control group for symptoms of depression, distress, mood, and self‐esteem in older adults with a diagnosis of major or minor depression. Number of arms: 3 Experimental arm: home‐based music therapy Control arm: self‐administered music listening (arm 2: outside the scope of this review; not music therapy); arm 3: wait‐list group, but attending a centre for older adults Consumer involvement: evaluating distress, self‐concept, mood, using patient‐reported BSI‐GSI, RSE, POMS Informed consent: yes, “All 30 individuals volunteered to participate in the research” Ethical approval: not reported Power calculation: not reported | |

| Participants | Description: patients Geographical location: Northern America, California, Palo Alto Methods of recruitment of participants: not reported Setting: Older Adult and Family Research and Resource Center Principal health problem: major or minor depressive disorder Diagnostic criteria for inclusion: not reported Diagnostic criteria for exclusion: not reported Severity of depression: major to minor depression Number of prior depressive episodes: not reported Comorbidity: not reported Age, range, mean (standard deviation): range = 61 to 86 years; mean 67.9 years; SD not reported Sex: female and male Sociodemographics intervention and control group: fair to good health, highly educated (all but 1 completed high school, and 7 had college degrees) Ethnicity: not reported Exclusion important groups: not reported Total numbers included in this trial: N = 32 Numbers included in music therapy: n = 11 (10, of whom 1 was lost to follow‐up + 1 was replaced) Numbers included in control group 1: n = 10 (outside the scope of this review) Numbers included in control group 2: n = 11 (10, of whom 1 was lost to follow‐up + 1 was replaced) | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm Intervention: music therapy Excluded intervention: any other form of treatment or psychoactive medication Name of intervention: home‐based music therapy Aims and rationale: stress reduction, provide pleasant experiences, compatible with dysfunctional thinking and depressed mood, to improve self‐esteem Method: receptive music therapy What was done:(materials) set of music‐facilitated techniques, when necessary cassette players, additional tapes;(procedures) appropriate music was selected by participants with assistance of a registered and board‐certified music therapist and after participants were interviewed. After observing relaxation response, music was recommended. Music therapist recommended music. Participants were instructed to find some time each day to practice techniques, also to complete a music listening log. The therapist introduced a single technique every week;(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face; (co‐interventions) no co‐interventions; (medication) no medication Location: at home Tailoring (how, when, why, what): The therapist interviewed participants individually to determine music preferences and previous experiences with music and helped them to identify compositions that had been paired with positive associations or meaningful memories. Whenever possible, familiar music, preferably from the participant's collection of recordings, was recommended to accompany the various techniques. Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: weekly Duration of session: ½ to 1 full hour Duration of treatment: 8 weeks Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: individual Who delivered intervention: music therapist Therapist training: registered and board‐certified Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: postdoctoral training in gerontology Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: completing a music listening log, using a 5‐point rating scale to monitor enjoyment and relaxation level of each piece of music and prescribed exercise. Participants were interviewed over the telephone regarding their compliance and satisfaction with the programme by an independent research assistant. Control arm Intervention: self‐administered listening techniques with moderate, indirect therapist contact; control arm 2: waiting list) Excluded intervention: any other form of treatment or psychoactive medication Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: not reported Type of TAU: not reported What was done:(materials) for control arm 1, 1 set of music‐facilitated techniques, cassette players, additional tapes; (procedures) the therapist spoke with the participant in weekly 20‐minute telephone conversations, discussing results of the music listening logs and effects of music; (mode of delivery) self‐administered every day; weekly telephone evaluation;(co‐interventions) no co‐interventions; (medication) no medication Location: at home Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: everyday self‐administered sessions; weekly one 20‐minute telephone call Duration of session: not reported Duration of treatment: 8 weeks Delivered number of sessions: 8 times 20‐minute telephone conversations Individual or group: individual Who delivered intervention: music therapist Therapist training: registered and board‐certified Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: postdoctoral training in gerontology Tailoring (how, why, when, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Monitoring of adherence to TAU: The therapist spoke with the participant in weekly 20‐minute telephone conversations, discussing results of the participant's music listening logs and effects of music. Participants were interviewed over the telephone regarding their compliance and satisfaction with the programme by an independent research assistant. | |

| Outcomes | Patient‐reported depression: GDS Overall distress: BSI‐GSI Self‐concept: RSE Mood: POMS | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: This research was supported by a National Research Service Award to Suzanne Hanser (Grant AG‐05469‐02) from the National Institute on Aging. Notable conflicts: not reported Other: See number of participants. Key conclusions: Participants in both music conditions performed significantly better than controls on standardised tests of depression, distress, self‐esteem, and mood. These improvements were clinically significant and were maintained over a 9‐month follow‐up period. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information about the sequence generation process was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. The method of randomisation was not reported. Quote: “Participants were assigned randomly to one of three conditions.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. Method of concealment was not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Study did not address this outcome. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No outcome data were missing. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A protocol for the study was not available, and the primary measure of depression was identified and reported as planned in the methods section. The BDI was related to this outcome but was utilised only for clinical practice, not for research purposes. Quote: “GDS was the primary measure of depression. The Beck Depression Inventory was administered weekly to all participants for the purpose of monitoring levels of depression only.” |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Risk of bias may be present, but information was insufficient for assessment of whether an important risk of bias exists. |

| Methods | Study design: randomised controlled trial, parallel groups Aim of study: The purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of using music techniques in a group intervention with adolescents who had been identified as exhibiting symptoms of depression. Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: group music therapy Control arm: cognitive‐behavioural group activities without music therapy Consumer involvement: evaluating depression, using patient‐reported BDI Informed consent: yes; “Parental consent was obtained for all the participants” Ethical approval: not reported Power calculation: not reported | |

| Participants | Description: junior high school students Geographical location: Northern America, a middle‐sized southwestern town Methods of recruitment of participants: not reported Setting: public junior high school Principal health problem: symptoms of depression Diagnostic criteria for inclusion: symptoms of depression Diagnostic criteria for exclusion: not reported Severity of depression: not reported Number of prior depressive episodes: not reported Comorbidity: not reported Age, range, mean (standard deviation): range 14 to 15 years; mean and SD not reported Sex: female, male Sociodemographics intervention group: not reported Sociodemographics control group: not reported Ethnicity: Anglo (n = 15), Hispanic (n = 3), Asian American (n = 1) Exclusion important groups: not reported Total numbers included in this trial: N = 20 Numbers included in music therapy: n = 10 Numbers included in control group: n = 10 | |

| Interventions | Music therapy arm Intervention: music therapy Excluded intervention: not reported Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: Researchers presented pleasant and potentially reinforcing music that served as stimuli for deep body relaxation, positive imagery and mood, and clear thinking, all of which are incompatible with worry. Method: combination of active and receptive music therapy What was done:(materials) for listening activities not reported; for improvisation piano and guitar; (procedures) as music was played, the group facilitator observed the participant who chose the song for responses indicating relaxation; (mode of delivery) face‐to‐face; (co‐interventions) short‐term individual psychotherapy; (medication) not reported Location: not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): Each of the participants was interviewed separately to determine music preferences and previous experience with music. Participants were then asked to choose a song that had special meaning for them and to share this song with the group. Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: weekly Duration of session: not reported Duration of treatment: 8 weeks Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: group Who delivered intervention: group facilitator, e.g. therapist Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: not reported Control arm Intervention: cognitive‐behavioural group activities Excluded intervention: music therapy Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: The focus of discussion every week was self‐concept and how depression affected self‐concept. Type of TAU: individual psychotherapy What was done:(materials) not reported;(procedures) every week, the facilitator focused on 1 adjective from a list of adjectives and how it was part of participants’ concept of who they were. Once the facilitator presented the adjective, participants discussed whether the adjective described them. At the end of each group session, a different participant was placed in the “hot seat” while the rest of the group participants used positive reinforcement to broaden the self‐concept of the participant in the “hot seat”;(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face;(co‐interventions) short‐term individual psychotherapy; (medication) not reported Location: not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: weekly Duration of session: not reported Duration of treatment: 8 weeks Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: group Who delivered intervention: group facilitator Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to TAU: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Patient‐reported depression: BDI | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: not reported Notable conflicts: not reported Other: missing SD for patient‐reported depression Key conclusions: “Music therapy techniques had made a significant difference.” | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information about the sequence generation process was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. The method of randomisation was not reported. Quote: “Participants were randomly assigned to one of the following treatment conditions…” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. The method of concealment was not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | The study did not address this outcome. Quote: “Participants in both the treatment and the control groups of the study completed the Beck Depression Inventory." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. For participants, blinding was not possible because of subjective outcomes. Quote: "All the participants in both the treatment and the control groups completed the BDI during the 1st week and 8th week of treatment." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No outcome data were missing. Quote: "All the participants in both the treatment and the control groups completed the BDI during the 1st week and 8th week of treatment." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A protocol for the study was not available, and all expected outcomes were identified and reported as planned in introduction and methods section. Quote: "The hypothesis of the study was that music therapy techniques would alleviate depressive symptoms more effectively than would nonmusic therapy techniques. All participants in both the treatment and the control groups completed the BDI during the 1st week and 8th week of treatment." |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Risk of bias may be present, but information is insufficient for assessment of whether an important risk of bias exists. |

| Methods | Study design: randomised controlled trial, quasi‐experimental design consisting of pretest and post‐test comparison, random assignment Aim of study: to examine the effects of addition of music therapy to an existing cognitive‐behavioural model of group psychotherapy for treatment of different age groups of adolescents for depression Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: music therapy Control arm: cognitive‐based therapy Consumer involvement: evaluating depression and self‐concept, using patient‐reported BDI, PHSCS Informed consent: yes; "After the consent form and treatment authorization were received the participant was randomly assigned to the group" Ethical approval: not reported Power calculation: not reported | |

| Participants | Description : junior and senior high school students Geographical location: Northern America, United States, a mid‐size city in the southwestern region Methods of recruitment of participants: recommended for treatment by referral from school counsellors Setting: public junior and senior high school Principal health problem: symptoms of depression Diagnostic criteria for inclusion: symptoms of depression Diagnostic criteria for exclusion: not reported Severity of depression: not reported Number of prior depressive episodes: not reported Comorbidity: no Age, range, mean (standard deviation): range 12 to 18, mean not reported Sex: female and male Sociodemographics intervention group: male and female Sociodemographics control group: male and female Ethnicity: Caucasion, Hispanic, African American, and Asian American Exclusion important groups: not reported Total numbers included in this trial: N = 63 Numbers included in music therapy: n = 31 Numbers included in control group: n = 32 | |

| Interventions | Music therapy arm Intervention: music therapy Excluded intervention: not reported Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: not reported Method: receptive music therapy What was done:(materials) recorded music that was chosen by one of the group members; (procedures) sessions consisted of 4 parts: (1) group participation exercise designed to build rapport; (2) listening to 1 piece of recorded music that was chosen by one of the group members; (3) discussion of depressive feelings and how those feelings could be cognitively and behaviourally challenged; (4) discussion about ways to change behaviour as related to the music and depressive feelings; (mode of delivery) face‐to‐face; (co‐interventions) each member was given the opportunity for counselling on an individual basis; (medication) not reported Location: not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): Group members were able to choose music. Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: weekly Duration of session: 1 hour Duration of treatment: 12 weeks Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: group Who delivered intervention: counsellor‐researcher Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: not reported Control arm Intervention: cognitive‐based therapy Excluded intervention: music therapy Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: not reported Type of TAU: not reported. See co‐interventions. What was done:(materials) not reported;(procedures) sessions consisted of 3 parts: (1) group participation exercise to build rapport, (2) discussion of 1 depressive feeling and how that feeling could be cognitively and behaviourally challenged, (3) discussion about ways to change behaviour as they related to the feeling; (mode of delivery) face‐to‐face;(co‐interventions) each member was given the opportunity for counselling on an individual basis; (medication) not reported Location: not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: weekly Duration of session: 1 hour Duration of treatment: 12 weeks Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: group Who delivered intervention: counsellor‐researcher Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to TAU: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Patient‐reported depression: BDI Self‐concept: PHSCS | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: not reported Notable conflicts: not reported Other: no Key conclusions: Participants in music therapy showed lower depression and higher self‐concept than participants in the groups that utilised cognitive‐based therapy. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information about the sequence generation process was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. The method of randomisation was not reported. Quote: “After the consent form and treatment authorization were received… the participant was randomly assigned to the group.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “Instruments in the packets were coded to insure the integrity of each protocol.” |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | The study did not address this outcome. For participants, blinding was not possible because of subjective outcomes. Quote: "Participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory..." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. For participants, blinding was not possible because of subjective outcomes. Quote: "All of the participants receive the instrument packet." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No outcome data were missing. Quote: "Upon examination, there were no missing instruments." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A protocol for the study was not available, and all expected outcomes were identified and reported as planned in introduction and methods section. Quote: "Upon examination, there were no missing instruments." |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Risk of bias may be present, but information is insufficient for assessment of whether an important risk of bias exists. |

| Methods | Study design: clinical controlled trial; parallel groups Aim of study: The principal objective of this research is to establish musical therapy as a valid psychotherapeutic treatment of depressive disorders, based on a clear methodological procedure and strict protocols suited to our population. Number of arms: 2 Experimental arm: music therapy plus antidepressants Control arm: antidepressants only Consumer involvement: evaluating depression, using patient‐reported BDI Informed consent: not reported Ethical approval: not reported Power calculation: not reported | |

| Participants | Description: patients Geographical location: Europe, Belgrade Methods of recruitment of participants: not reported Setting: Centre for Disorders and Borderline Cases Principal health problem: depression Diagnostic criteria for inclusion: depression Diagnostic criteria for exclusion: professional musicians; psychotically retarded, agitated, or paranoid to such a degree that it would hinder communication inside the group and have a destructive effect; no more than 2 expressly suicidal participants in a group Severity of depression: moderately to severely depressed, including psychotic depression Number of prior depressive episodes: not reported Comorbidity: unclear whether anxiety was a comorbidity Age, range, mean (standard deviation): range 21 to 62; mean 40 years Sex: female and male Sociodemographics intervention group:marital status: single (n = 8), married (n = 13), divorced (n = 8), widowed (n = 1); children: no children (n = 12), 1 child (n = 6), 2 or more children (n = 12); educational degree: primary school (n = 6), secondary school (n = 11), skilled worker (n = 1), higher skilled worker (n = 3), college of higher education (n = 1), university degree (n = 8); social status (n= 3), pupil/ student (n = 3), employed (n= 20), unemployed (n= 6), retired (n = 1); residence: house/apartment owner (n = 18), sitting tenant (n = 2), subtenant (n = 10) Sociodemographics control group:marital status: single (n = 3), married (n = 17), divorced (n = 7), widowed (n = 2); children: none (n = 5), 1 (n = 7), 2 or more (n = 18); educational degree: primary school (n = 14), secondary school (n = 10), skilled worker (n = 3), higher skilled worker (n = 0), college of higher education (n = 0), university degree (n = 2); pupil/student (n = 0), employed (n = 20), unemployed (n = 4), retired (n = 4); residence: house/apartment owner (n = 23), sitting tenant (n = 2), subtenant (n = 4) Ethnicity: not reported Exclusion important groups: no Total numbers included in this trial: N = 60 Numbers included in music therapy: n = 30 Numbers included in control group: n = 30 | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm Intervention: music therapy Excluded intervention: not reported Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: not reported Method: receptive music therapy What was done:(materials) not reported;(procedures) group analytical listening to music, using guided fantasies;(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face;(co‐interventions) treatment as usual, e.g. antidepressives and supportive‐cognitive therapeutic forms, hospitalisation (medication) antidepressive medicaments. The antidepressive medications that participants were given belonged to the tricycline and tetracycline groups and were orally applied; the initial dosage was 100 mg, which grew to 150 to 300 mg, which was a full therapeutic dosage. Participants were also given anxiolytics, 30 mg per day, and, when necessary, sedative neuroleptics, 25 to 150 mg per day. Location: “In a room situated in the villa 'Avala', which was turned into a musical therapy cabinet and fulfilled the basic isolation and acoustic criteria.” Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: Protocols were presented at regular supervisions. Intensity of sessions: twice a week Duration of session: 20 minutes Duration of treatment: 6 weeks Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: group Who delivered intervention: a skilled therapist Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to music therapy paradigm/protocol: The protocol was written down after each session, so that the course of the therapeutic process was documented. Control arm Intervention: Treatment as usual, e.g. antidepressives and supportive‐cognitive therapeutic forms (hospitalisation) Excluded intervention: music therapy Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: not reported Type of TAU: antidepressant medication plus hospitalisation What was done:(materials) antidepressives; (procedures) the antidepressive medications that participants were given belonged to the tricycline and tetracycline groups and were orally applied; the initial daily dosage was 100 mg, which grew to 150 to 300 mg, which was a full therapeutic dosage. Participants were also given anxiolytics, 30 mg per day, and, when necessary, sedative neuroleptics, 25 to 150 mg per day. They were treated with medicaments (in the above specified dosages), as well as supportive‐cognitive therapeutic forms; (mode of delivery) not reported; (co‐interventions) not reported; (medication) see above Location: not reported Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: not reported Intensity of sessions: not reported Duration of session: not reported Duration of treatment: not reported Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: not reported Who delivered intervention: not reported Therapist training: not reported Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported Monitoring of adherence to TAU: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Patient‐reported depression: BDI Anxiety: HAM‐A | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: not reported Notable conflicts: no Other: missing SD for clinician‐rated depression, patient‐reported depression, anxiety Key conclusions: The depressive disorder participant group simultaneously treated by medications and musical therapy showed much better results compared with the control depressive participant group, which was treated with medications and supportive‐cognitive psychotherapeutic methods. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Random sequence generation was not truly random. Quote: “We had a total of sixty patients, divided into two groups of thirty.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. The method of concealment was not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | The study did not address this outcome. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No outcome data were missing. Quote: "The analysis comprised a sample group of 30 patients suffering from depression, treated with musical therapy, while the control group consisted of a sample of 30 depressive patients, treated with standard medication...For the purposes of establishing the quality of the acquired data, a Kolmogorov‐Smirnov normal distribution test was done, which established that both samples were characterized by normal distribution." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A protocol for the study was not available, and all expected outcomes were identified and reported as planned in the methods section. Quote: "Depression and anxiety estimation scales. Consisting of special forms that the patients were asked to fill in upon reception and on the third and sixth weeks of therapy (BECK, HAMD, HAMA I, III, VI)" and Table 3 |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Risk of bias may be present, but information is insufficient for assessment of whether an important risk of bias exists. |

| Methods | Study design: randomised controlled trial Aim of study: To judge the effectiveness of cognitive therapy, the treatment group was compared with two control group. Number of arms: 3 Experimental arm: cognitive therapy Control arm: music therapy (1), treatment as usual (2) Consumer involvement: evaluating depression, using patient‐reported BDI Informed consent: unclear. “…they were asked to participate” Ethical approval: yes; “Approval for their involvement in this study was obtained from the Institutional Board of Wright State University, as well as from the administration of the nursing home” Power calculation: not reported | |

| Participants | Description: residents of a nursing home Geographical location: Northern America, Miamisburg, Ohio Methods of recruitment of participants: not reported Setting: nursing home Principal health problem: clinical depression Diagnostic criteria for inclusion: moderate to severe depression Diagnostic criteria for exclusion: organic brain syndrome Severity of depression: moderately to severely depressed Number of prior depressive episodes: not reported Comorbidity: not reported Age, range, mean (standard deviation): range 70 to 82, mean 77 years Sex: men, and for female unclear Sociodemographics intervention group: not reported Sociodemographics control group: not reported Ethnicity: “There were two black men in the group; all others were white.” Exclusion important groups: no Total numbers included in this trial: N = 60 Numbers included in music therapy: n = 20 Numbers included in control group 1: n = 20 Numbers included in control group 2: n = 20 | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm Intervention: psychological therapy Excluded intervention: not reported Name of intervention: not reported Aims and rationale: not reported Type of therapy: group cognitive‐behavioural therapy What was done:(materials) not reported;(procedures) help residents discard automatic thoughts of a self‐defeating nature, replace thoughts with more realistic ones, and adopt new behaviours, especially in relating to other people in 4 phases: phase 1: preparation of residents for cognitive therapy; phase 2: basic techniques for changing behaviour; phase 3: basic techniques for changing cognition; phase 4: preparation of residents for termination of treatment;(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face;(co‐interventions) not reported;(medication) not reported Location: private meeting rooms Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported Modification intervention: not reported Quality of delivery: Preparation of group leaders was carried out in videotaped sessions, instructions, role playing, brief lectures, blackboard demonstrations, case studies, and homework assignments of reading the cognitive therapy manual and listening to cassette tapes on techniques. Performance of leaders was rated by their group members. Intensity of sessions: twice weekly Duration of session: 1½ hours Duration of treatment: 10 weeks Delivered number of sessions: not reported Individual or group: group of 20, divided into 3 smaller groups Who delivered intervention: group leaders: professional personnel of the nursing home; nurses; 2 RNs and 1 social worker Therapist training: 1 Associate degree in nursing and a Bachelor of Science in education; 1 diploma in nursing; social worker had a Bachelor of Arts degree in social psychology and experience in the field of social work Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: varied from a first job to semiretirement Monitoring of adherence to paradigm/protocol: Attendance records were kept to determine if residents would attend the groups regularly. Control arm Intervention: control arm 1 music therapy (control arm 2 between brackets: treatment as usual) Excluded intervention: not reported (not reported) Name of intervention: not reported (not reported) Aims and rationale: not reported (not reported) Method: receptive music therapy (rehabilitation services, such as whirlpool therapy designed to improve functional level or to arrest deterioration) What was done for music therapy:(materials) not reported (not reported);(procedures) residents listened to many kinds of music, including old‐time favourites, hymns, and country melodies. One resident also played popular and semiclassical piano music (not reported)(mode of delivery) face‐to‐face (not reported);(co‐interventions) not reported (not reported);(medication) not reported (not reported) Location: not reported (not reported) Tailoring (how, when, why, what): not reported (not reported) Modification intervention: not reported (not reported) Quality of delivery: not reported (not reported) Intensity of sessions: twice weekly (not reported) Duration of session: 1 hour (not reported) Duration of treatment: 10 weeks (not reported) Delivered number of sessions: not reported (not reported) Individual or group: group therapy in a group of 20 participants (not reported) Who delivered intervention: for music therapy, a trained professional (not reported) Therapist training: for music therapy trained, no further information (not reported) Therapist's post‐qualifying experience: not reported (not reported) Monitoring of adherence: not reported (not reported) | |

| Outcomes | Patient‐reported depression: BDI | |

| Notes | Funding for trial: not reported Notable conflicts: not reported Other: missing SD for patient‐reported depression Key conclusions: Cognitive therapy was found to be effective in older people. Residents attended sessions regularly, and the change in the depression level for group participants was highly significant statistically and clinically noticeable. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information about the sequence generation process was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk'. The method of randomisation was not reported. Quote: "Those who qualified as moderately to severely depressed and free from organic brain syndrome were randomly assigned to one of three groups." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. The method of concealment was not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | The study did not address this outcome. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Information was insufficient to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups Quote: "Only one resident dropped out ... the corresponding subjects in the other two groups were therefore also discarded in the data analysis, leaving 19 subjects in each group for the purpose of data analysis." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A protocol for the study was not available, and all expected outcomes were identified and reported as planned in the methods section. Quote: The Beck Depression Inventory was administered to all participants ... to compare with the initial score" and Table 1 |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Risk of bias may be present, but information is insufficient for assessment of whether an important risk of bias exists. |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BSI‐GSI: Brief Symptom Inventory‐Global Severity Index; FJFR: Fundación José Felix Ribas; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS‐A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ Anxiety; HAM‐A: Hamilton Anxiety Scale; HAM‐D: Hamilton Depression Scale; HRSD: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; ICD‐10: International Classification of Disease, Tenth Edition; IRB: institutional review board; MADRS: Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MAR: Artistic Music Therapy; MDD: major depressive disorder; PHSCS: Piers‐Harris Self‐Concept Scale; POMS: Profile of Mood States; RAND‐36: health‐related quality of life survey distributed by RAND; RSE: Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Inventory; SD: standard deviation; SF‐36 Thai: Thai version of the Short Form‐36 Health Survey; SNRI: serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TAS‐20: Toronto Alexithymia Scale; TAU: treatment as usual; TDI: Thai Depression Inventory.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had a primary diagnosis of dementia but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were students but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were adults but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were adults not known to be suffering from any mood‐related disorders. Outcome was depression. | |

| No full text, i.e. dissertation available | |

| The intervention was not music therapy, but music listening. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had a primary diagnosis of dementia. Outcome was depression. | |

| Not a randomised controlled trial, i.e. qualitative study assessing a therapeutic drumming programme for Parkinson's disease to address non‐motor symptoms, including depression and anxiety | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had persistent post‐traumatic stress disorder but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were adults who had hematological malignancy but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| The intervention was not music therapy, but music listening. No therapist was involved. | |

| No relevant comparator intervention | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were adult inmates who were depressed or had anxiety. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had mental disorders, but not all participants were depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had dementia but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had cancer but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were cognitively impaired older adults, but not all participants were depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| The intervention was not music therapy, but music listening. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had complicated grief and mental illness but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| No full text available | |

| No full text available | |

| The intervention was not music therapy, but music listening. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were nursing home residents, but not all participants were depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Not a randomised controlled trial, i.e. a response to the Maratos 2008 review | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had a primary diagnosis of dementia but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants had a primary diagnosis of cancer but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were local farm workers but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| Ineligible study population, i.e. participants were older people who were nursing home residents but were not depressed. Outcome was depression. | |

| No relevant comparator intervention |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Methods | Design: RCT, mixed method |

| Participants | Description: older adults |

| Interventions | Experimental group: music therapy choir intervention Control group: standard daily care |

| Outcomes | Clinician‐rated depression: Cornell Scale Quality of life: Cornell Brown Cognitive functioning: Mini Mental State Examination |

| Notes | Based on abstract only Design: unclear whether RCT Description: unclear whether adults were depressed or depression was an outcome Intervention: unclear whether intervention group received music therapy only or music therapy and TAU |

| Methods | Design: quasi‐experimental design |

| Participants | Description: people with cancer, depression, and anxiety |

| Interventions | Experimental group: listened to light music at least 20 minutes per day for 3 days Control group: not reported |

| Outcomes | Depression: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Anxiety: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |