Rehabilitación física para personas de edad avanzada en la atención a largo plazo

References

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to studies awaiting assessment

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: assent accepted Inclusion criteria: urinary incontinence Exclusion criteria: cognitive = comatose, severe physical aggression; medical = life expectancy < 3 months, length of stay < 3 months % Eligible within home: 49.6 Intervention: N = 15; % women = 92.9; age (mean) = 88.6 years ± 10.4 | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to test whether an intervention combining increased daytime physical activity with improvement in the night‐time environment improves sleep and decreases agitation in nursing‐home residents Intervention group: FIT programme, individualised intervention, session duration = n/a, number of sessions per week = maximum of 20 Control group: usual care for 14 weeks, then 1 week of night‐time programme | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: 10‐minute walk/wheel (time), 10‐minute walk/wheel (average distance) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

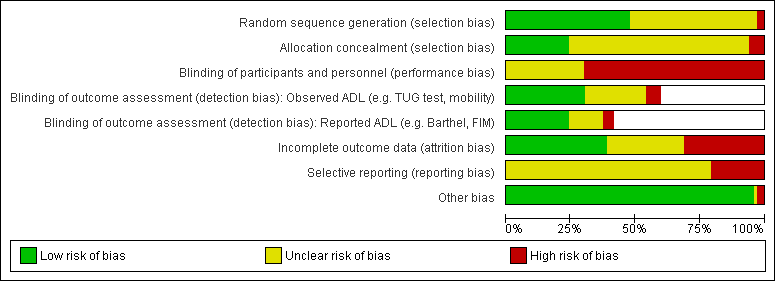

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Randomization occurred after baseline assessment" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Randomization occurred after baseline assessment" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Study was performed in a single home with an observable intervention |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "...performed by independent evaluators..." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 25 participants lost prior to baseline assessment because of time taken for parent study. 4 further participants lost to follow up, but unclear if already randomised and if so from which group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable. Some baseline assessments could have been outcome measures (e.g. OSAI) |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: randomised, assessor‐blind trial, matched pairs | |

| Participants | Country: Hong Kong Inclusion criteria: able to understand and follow verbal instructions, ambulate independently (with or without aids), tolerate standing, and walking for at least 5 minutes Exclusion criteria: medical= acute musculoskeletal pain, neurological signs and symptoms not under medication control, unstable medical conditions, complaint of dizziness and blurred vision leading to difficulty walking, medical conditions contraindicative to physical activity % Eligible within home: not reported Intervention: N = baseline not reported; % women = not reported; age (mean) = 79.1 years ± 8.41 Control: N = baseline not reported; % women = not reported; age (mean) = 81.0 years ± 7.45 | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to examine the effects of a short‐term mobility programme on the balance and mobility of elderly residents in private old‐age homes in Hong Kong Intervention: M programme (N = 10) = lower limb strengthening and balance training based on the overloading principle for strengthening and specificity for challenging balance in the upright position Control: C programme (N = 8) = general light exercises performed while sitting without progression Training session adherence: 98% | |

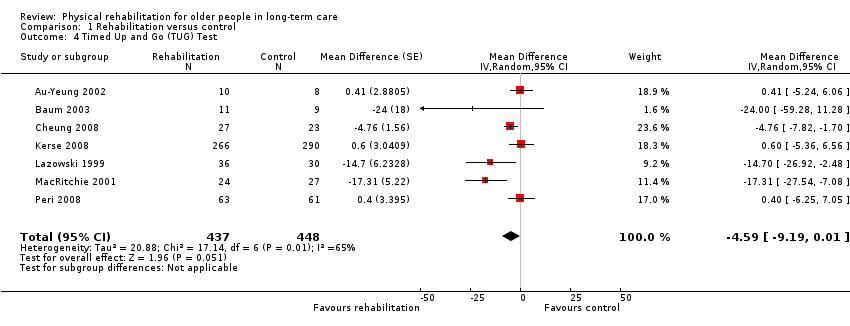

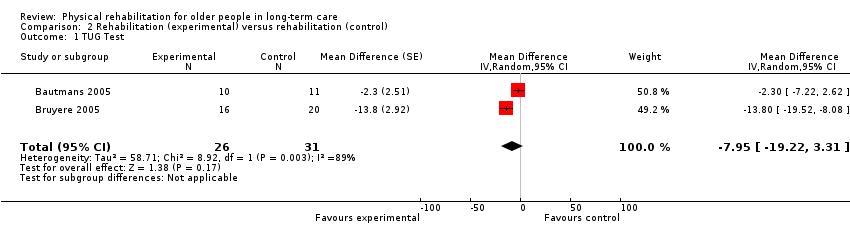

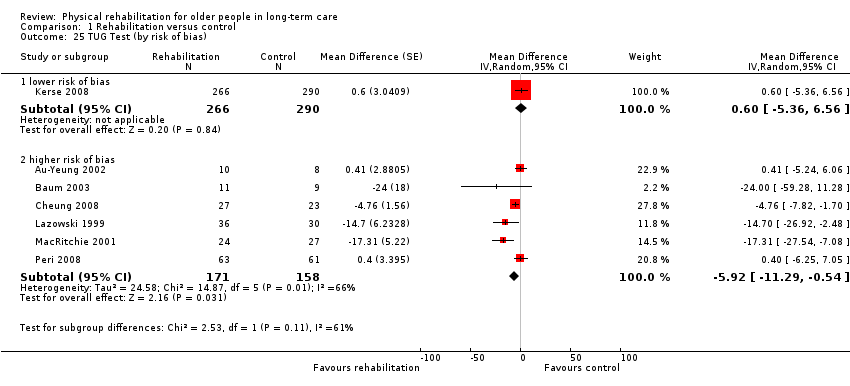

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: TUG test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991), 4 metre walk (time seconds) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Subjects of each matched pair were randomly allocated...by drawing of lots" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "...by drawing of lots..." Unclear if concealed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned. Both participant groups received exercise interventions |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "They were blinded to the allocation of subjects to the exercise programmes" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 31 participants consented; 13 dropped out (unclear numbers per group). Analysed as treated |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The three measures were appropriate. However, may not have been exclusive. Protocol not available |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: randomised controlled semi‐cross‐over trial | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: not specified Inclusion criteria: age > 65, residence at facility > 3 months, ability to ambulate alone (included with assistive devices or carer) Exclusion criteria: cognitive = inability to follow 2‐step command; medical = acute unstable illness (e.g. pneumonia),chronic illness (e.g. uncompensated congestive heart failure); functional = assaultive behaviour pattern, unwillingness to discontinue current physical therapy % Eligible within home: 42 Intervention: N = 11; % women = 82; age (mean) = 88 years, range = 75 to 96 years Control: N = 9; % women = 67; age (mean) = 88 years, range = 78 to 99 years | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to determine whether a strength and flexibility programme in frail long‐term care facility residents would result in improved function Number of experimental groups: 2 Intervention: conducted by exercise physiologist in the lounge, exercises done in seated position (frailty), warm‐up; upper body strengthening; lower‐body strengthening; cool down, soft ankle and wrist weights (2 to 4 lbs), Thera‐Bands® (resistance 2.5 to 9 lbs), weighted hand‐sized balls, beach balls for kicking and throwing, weekly evaluations of progress Control: art therapist or social worker; sessions of drawing, painting, puzzles, or cards; encouraged to continue normal activities; discouraged from joining exercise regime during the intervention | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: Physical Performance Test, TUG test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was determined by a computer‐generated algorithm (permuted blocks) stratified by place of residence within the LTC facility" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Assignment to the study group was done by opening sealed envelopes with the random numbers supplied in sequence by the study coordinator" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Participants were not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "All the performance tests were administered by physical and occupational therapists who were blinded to the group assignments. The MMSE was administered by two trained medical students and research nurses also blinded to group membership" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | 13% of total repeated measures after baseline missing because of death or acute illness, but not reported which groups. ITT analysis performed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | High risk | Quote: "Two patients were non‐compliant with their assignment; one switched to exercise immediately...results...included these patients as they were assigned...When they were eliminated from analysis, the results were slightly more positive in favour of the exercise intervention" Evidence of contamination reported |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: Belgium Inclusion criteria: dependent in no more than 2 of 6 ADL categories (Katz Scale) Exclusion criteria: cognitive = cognitive dysfunction interfering with test and training procedures; medical = presence of infectious disease, insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus, endogenous osteosynthetic material, knee or hip prosthesis, pacemaker, epilepsy, musculoskeletal disorders % Eligible within home: 33.7 Intervention: N = 13; men:women ratio = 5:8; age (mean) = 76.6 years ± 11.8 Control: N = 11; men:women ratio = 4:7; age (mean) = 78.6 years ± 10.4 | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to investigate the feasibility of whole body vibration in the institutionalised elderly and its impact on functional capacity and muscle performance Targeted social interaction Intervention: used Power Plate vibration platform, sessions 3 times a week with at least 1 day of rest between; 6 static exercises targeting lower limb muscles, exercise volume, and intensity gradually increased Control: the same exercise regimen on the same vibration platform but machine switched off and sound produced by tape recorder | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: TUG test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported, were given the loan of the vibration platform by 'Power Plate Belgium' | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was done for all 24 participants together at the same moment by lottery" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding of participants attempted ‐ reproduced sound of vibration platform to convince control group that it was working, but participants may have felt that it was not working |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Functional performance assessment was done by a physical therapist who was unaware of group assignment of the participants" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Three dropouts in whole body vibration group compared with no dropouts in control group ‐ two dropouts likely to be related to whole body vibration program |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Inclusion criteria: residential status, > 65 years old, ambulatory (± assistive device) Exclusion criteria: history of heart attack/stroke within previous 6 months, unstable angina, any condition that the physician felt might be worsened by exercise % Eligible within home: not reported Training group 1: N = 8; mean age = 84 years ± 9.6; range = 71 to 96 years; 6 women, 2 men Training group 2: N = 8; mean age = 80 years ± 6.6; range = 69 to 90 years; all women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to evaluate the effect of a 8‐week progressive functional fitness strength programme using dumbbells and ankle weights on strength, functional capability, balance, and selected psychological variables in residents in an assisted‐living facility Intervention: both groups followed the same exercise routine, only the weights varied (see Notes), the exercise routine comprised 5 upper and 5 lower body strengthening exercises targeting the major muscle groups, using different weights of dumbbells as resistance, cadence exercises wearing ankle weights were also performed, a gerontologist specialising in exercise training for older adults led the exercise sessions, which included all of the participants in 1 large group (see Notes) Training group 1: the dumbbell and ankle weights and number of exercise repetitions were gradually increased over the course of the study (Control) Training group 2: Used 1 lb dumbbells throughout the study, and cadence exercises were performed wearing ankle straps without the addition of weights | |

| Outcomes | Falls: number of falls | |

| Notes | Funding: University of North Texas Research and Professional Development Grant | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Subjects were entered into training group 1 or training group 2 through random assignment by a random number table" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | The two treatment groups trained together ‐ participants may have noticed that different groups were receiving different weighted dumbbells and wearing different ankle weights |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No report of blinding of assessors |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Interviewer not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | No report of missing data. No reports of attrition and exclusions |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Prespecified measures 'balance' and 'number of falls' not reported at 8 weeks |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: residents with self‐care dependency needs Nursing and residential homes: +5 beds with residents > 65 years with self‐care dependency needs | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to investigate the feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of group exercise for residents in care homes 2 groups: Intervention: exercise group (N = 28) Control: control group (N = 28) | |

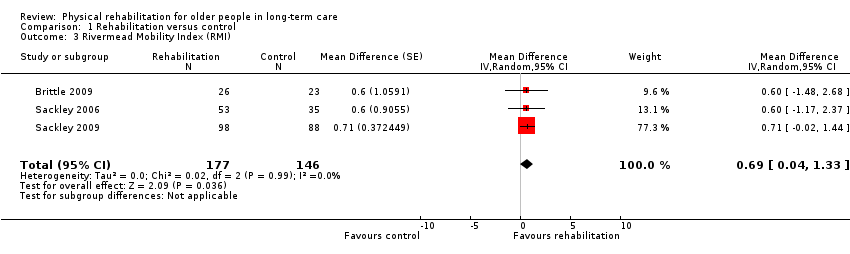

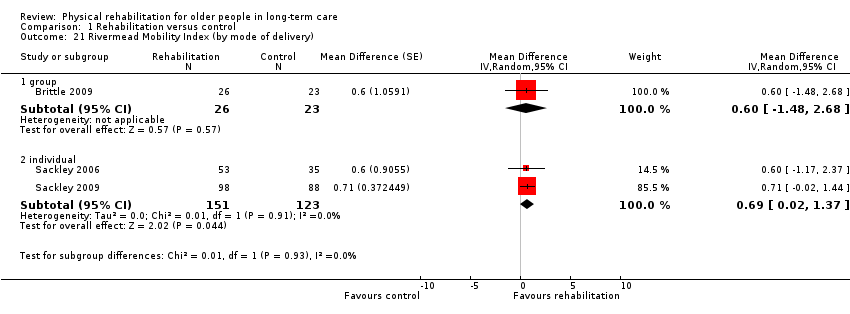

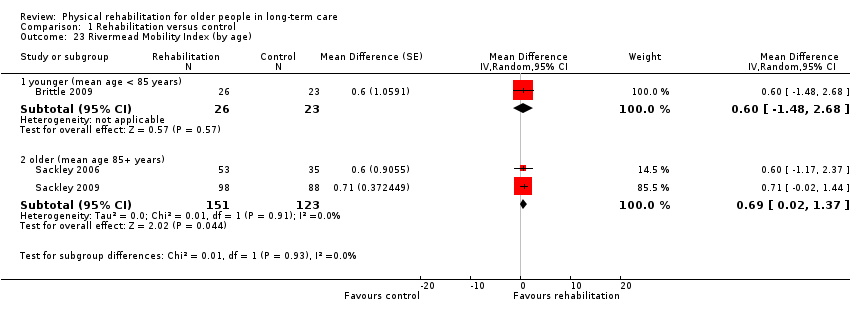

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: RMI (Collen 1991) | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was performed...using computer‐generated random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was performed by an independent principal statistician from Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Personnel designed and delivered the intervention to exercise, but control received usual care, so personnel knew. No report of blinding of participants ‐ although, intervention and control groups were in separate homes, so may not have been aware of which group they were in |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Assessments were conducted...by one of two research staff... masked to group allocation" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Same number of losses to follow up in each group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Inclusion criteria: their current health status did not preclude participation, aged = 60, could speak and understand English, cognitively comprehend and answer questions, communicate verbally or in writing, were willing to participate in indoor gardening activities for 6 weeks Exclusion criteria: see inclusion criteria % Eligible within home: not reported Experimental group 1: N = 33, men = 6 | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: the effects of indoor gardening on socialisation, activities of daily living, and perceptions of loneliness Phase 1: residents in home A comprised experimental group 1 and participated in an indoor gardening project once a week for 5 weeks; home B, the control group, received 20‐minute visits over the same 5‐week period Phase 2: residents of home B became experimental group 2 and participated in indoor gardening twice a week for 2 weeks Intervention: decorating flowerpots and planting bulbs of their choice, choosing and transplanting colourful flowering plants, discussing proper care of plants, viewing video on gardening, arranging plants in a hanging basket, arranging fresh cut flowers and greenery Control: 20‐minute visits during the 5‐week intervention period to control for social interaction and changes due to the presence of experimenters; control group then invited to participate in the gardening (phase 2) | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: MDS: transfer item (Brown 2004), MDS: eating item (Brown 2004), MDS: locomotion item (Brown 2004), MDS: grooming item (Brown 2004), MDS: dressing item (Brown 2004), MDS: bathing item (Brown 2004), MDS: Physical Functioning scale (6 items, Brown 2004) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A coin toss was used to determine the assignment of each nursing home" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Coin toss ‐ allocation could have been foreseen by researchers |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unblinded participants and personnel |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Outcome assessor unreported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | No report of loss to follow up or otherwise |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Only some sub‐scales reported for some comparisons |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: Denmark Inclusion criteria: see exclusion criteria Exclusion criteria: cognitive = moderate/severe cognitive impairment; medical = acute illness, hypertension, severe cardiovascular disease, severe impairment of motor function, neurological disorder % Eligible within home: not reported Intervention: N = 10; men:women ratio = 1:9; age = 88.6 years (86 to 95 years) Control: N = 11; men:women ratio = 1:10; age = 90.6 years (86 to 95 years) | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to test the hypothesis that physical exercise induces an anti‐inflammatory response that is associated with reduced chronic activation of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐alpha system in frail elders and that the increase in muscle strength after resistance training is limited by systemic low‐grade inflammation Number of experimental groups: 2 Exercise features: training protocol from Harridge 1999. 3 exercise sessions a week for 12 weeks, low repetitions with high weight resistance, seated upright in training chair. 3 sets of 8 knee extensions Non‐exercise features: subgroup of participants gave blood samples for examining inflammatory marker Control: occupational therapist supervised social activities twice a week for 12 weeks; no physical training | |

| Outcomes | Muscle power (anaerobic): knee flexor muscle strength, knee extensor muscle strength | |

| Notes | Funding: Danish Medical Research Council NOVO Foundation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Participants were randomly assigned..." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No report of blinding of participants, but social control intervention with physical outcome measures, so intervention would have been obvious |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Excluded results of the two men from the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT Treatment group significantly older than control group (P = 0.03) Losses to follow up: 6 (14%) | |

| Participants | Country: Belgium Randomised: 42 Consent: not specified Inclusion criteria: ambulatory, no major cognitive disorders that would effect their ability to complete questionnaires Exclusion criteria: medical = people with a high risk or thromboembolism, history of hip or knee replacement % Eligible within home: not reported Intervention (vibration therapy plus physiotherapy): N = 22; % women = 81; age: mean: 83.6 years ± 4.8 years Control (physiotherapy alone): N = 20; % women = 65; age(mean) = 78.9 years ± 6.9 years | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to investigate the effects of whole body vibration in the elderly Groups: randomised to receive vibration intervention plus a standard physical training regimen or physical training alone Exercise features: Intervention – controlled whole body vibration: at each session stood on vertical vibrating platform for 4 series of 1 minute of vibration alternating with 90 seconds of rest, vibration set at 10 Hz for the first and third series with peak to peak amplitude of 3 mm; for second and fourth series, vibration set at 26 Hz with peak to peak 7 mm, blood pressure and pulse were taken before the first series, immediately after the second and fourth series, and 2 minutes after the fourth series in each session Physical therapy: standard exercise programme, gait and balance exercises, training in transfer skill, strengthening exercises with resistive mobilisation of lower limbs, 3 times weekly for 10 minutes during the 6‐week study, provided by only 1 physical therapist | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: TUG test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported; no commercial party had any financial interests | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided on randomisation procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No evidence of blinding. The potential influence of the additional treatment in the intervention group, and outcome expectations of the intervention provider could have influenced participant response |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Lost to follow up from intervention (27%); none lost from control. ITT analysis undertaken utilising last available data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Some results were reported as ITT analysis, others as per‐protocol (possible selective reporting) |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: assent accepted Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of dementia, family consent, stable on medications, resident in the home for 3 months Exclusion criteria: medical: use of tacrine, a drug used in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (centrally acting anticholinesterase) % Eligible within home: not reported | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to assess the impact of a highly structured interdisciplinary programme of sensorimotor activities on the function and behaviour of nursing‐home residents with dementia Number of experimental groups: 2 Intervention: first 10‐week period: Intervention provided by certified therapeutic recreation specialists in collaboration with the unit managers; design based on level of functioning, personal care schedule, and interests; small group activities among people of similar functioning; co‐ordinated schedule of care established for the treatment group including all aspects of care and therapeutic programming; staff were encouraged to walk with residents, interact socially, and promote functional independence during activities; intervention participants received therapeutic programming and diversional stimulatory activities throughout the day and evening; every aspect of the day considered programming and outcome‐based – all sensory motor activities, no matter how mundane (e.g. hand washing, waking to meals); cooking, herb gardening, group cognitive therapy, fitness sessions, various sensory (water, relaxation activities); second 10‐week period: home staff took over 50% of the programming; third 10‐week period: nursing‐home staff took over all aspects of the programming Control: usual care: same schedule of regular nursing‐home activities and standard nursing care | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: timed walk over 50 feet | |

| Notes | Funding: National Alzheimer's Association | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...by name draw without replacement" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No blinding of participants |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | All evaluators blind to group assignment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | All evaluators blind to group assignment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | 12 participants died, and 2 were not stable on medications ‐ data from these 14 eliminated from final data analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | MOSES outcomes not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Risk of contamination: randomisation of individual residents, but intervention involved some staff training, so possibility of confounding |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: visually‐impaired elderly | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to examine the effects of an exercise programme, which focused on improvement of the functional balance of visually‐impaired elderly people Intervention: exercise training (experimental) (N = 27) | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: TUG (Timed Up and Go) test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991) Falls, risk and fear of falling: falls (any episodes for participant) | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided on random sequence generation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Participants were randomly assigned...by drawing from a sealed opaque envelope that contained the number that determined the allocation" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Both control and experimental exercise programmes were designed and conducted by two physiotherapists |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Assessment of the functional status of the subjects was conducted by a third physiotherapist who was blinded to the grouping of the subjects" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No losses to follow up in either group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: older adults

(5 and 6 were evaluated by their general practitioner) | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to examine the effect of different training protocols on quality of life, vitality, and depression of older adults living in long‐term care facilities Control 2 (of 3): strength training (N = 57) | |

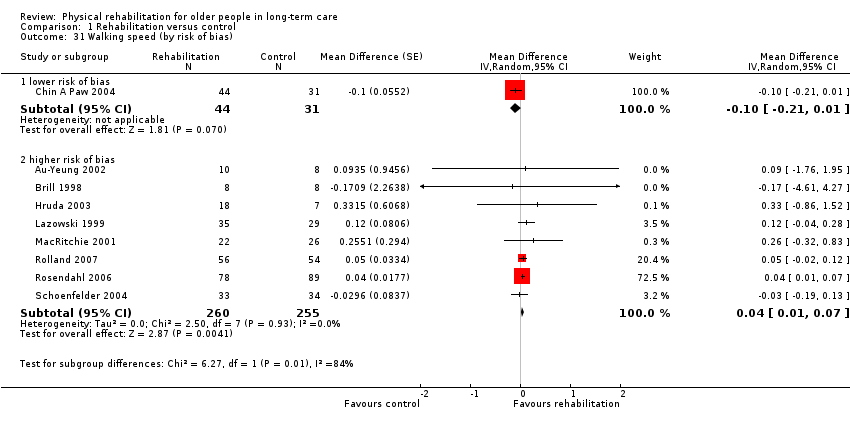

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: walking speed over 8 metres, disability in 17 ADLs (Chin A Paw 2006), putting on and off a coat, picking up a pen from the floor while standing | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The random allocation sequence was generated by computer" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Two independent students assigned participants to their group ‐ implies allocation was concealed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No mention of blinding of participants, but there were four different groups so participants may not have been aware which ones were experimental and which was the control |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Data were collected at baseline and after 6 months intervention by three trained research assistants who were blinded to group assignment" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Data were collected at baseline and after 6 months intervention by three trained research assistants who were blinded to group assignment" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Dropout of participants was not significantly different among the four groups". Similar reasons for dropout between groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Stated that they were going to report body composition measurements ‐ only referred to in text in associated paper (Chin A Paw 2006) |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: Cluster RCT Strength of ankle dorsiflexors (control group stronger) Balance (control group had better balance both with eyes open and eyes closed) Mobility (control group more mobile) Losses to follow up: 9 (13.2%) | |

| Participants | Country: South Korea Consent: assent accepted Inclusion criteria: ambulatory adults aged over 60 with at least 1 of the following: impaired gait (score of < 10 on gait sub‐scale (maximum score of 12) of the Performance Orientated Assessment of Mobility (POAM)), impaired balance (score of < 14 on POAM balance sub‐scale (maximum 16), history of falling in the previous year, postural hypotension (drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mmHg from lying to standing, use of 4 or more prescription medications that may affect balance Exclusion criteria: cognitive = severe dementia (score < 20 on Folstein MMSE); medical = inability to complete 12 weeks of exercise because of physical illness; functional = current involvement in any type of regular exercise % Eligible within home: not reported Intervention: N = 29; % women = 79; age (mean) = 76.96 years ± 7.7 years Control: N = 30; % women = 70; age (mean) = 78.73 years ± 6.9 years | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to determine changes in physical fitness (knee and ankle muscle strength, balance, flexibility, and mobility), fall avoidance efficacy, and fall episodes of institutionalised adults after participating in a 12‐week Sun‐style Tai Chi exercise programme Number of experimental groups: 2 Exercise features: Sun style Tai Chi, 10 minutes warming up, 20 minutes of 12 Tai Chi movements, 5 minutes of cooling down, done to music for soothing effect Control: maintained routine activities; did not participate in any regular exercise classes | |

| Outcomes | Falls: falls (any episodes for participant) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Selected two facilities (based on number of residents, location, and facilities) and randomly assigned them to either the experimental or control group by coin tossing |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Coin toss ‐ allocation could have been foreseen by researchers |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: "Participants were aware of their group assignment" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Professional team rather than the research team measured physical fitness" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 'As treated' analysis done ‐ measures not reported for all participants initially included, but only two departed from allocation |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: institutionalised elderly people with mixed dementia | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to analyse the effects of multidisciplinary or physiotherapeutic rehabilitation interventions on the cognition and balance of institutionalised elderly people with mixed dementia | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: TUG test (steps) (Christofoletti 2008), TUG test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991) | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A sealed envelope with an identification number was assigned to each subject, each one filled with a slip giving the group. When a patient was registered and given a number, the appropriate envelope was opened" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "A sealed envelope with an identification number was assigned to each subject, each one filled with a slip giving the group. When a patient was registered and given a number, the appropriate envelope was opened" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: "As a common bias presented on most rehabilitation trials, it was not possible to 'blind' the subjects regarding the treatments" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Assessors were 'masked' with respect to the data collected and to those patients that were included or not in this trial" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Because of small initial group sizes (mean = 18), the loss of 5 from each intervention group compared with the loss of 3 from the control group may present potential bias |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: assent accepted Inclusion criteria: capable of communicating and following simple instructions Exclusion criteria: hypertension, debilitating arthritic impairment, requiring cardiac medication % Eligible within home: not reported Activity group: N = 10; 5 women Social group: N = 6; 4 women Control group: N = 7; 3 women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: hypothesised that 12‐week physical activity programme would (1) increase total daily activity level, (2) upgrade participant self care, and (3) increase activity tolerance levels Number of experimental groups: 3 Activity group: stretching and postural exercise, modified weight and circuit training, dancing and walking; led by a therapist trained in physical education instruction and an assistant, for 1 hour, 5 sessions per week for 12 weeks Social group: recreational activities involving no physical exertion, e.g. board games, arts and crafts; led by a recreational therapist and an assistant, for 1 hour, 5 sessions per week for 12 weeks Control group: usual care | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: self‐care personal neatness evaluation (NOSIE‐30) | |

| Notes | Funding: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) Hospital improvement grant Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Subjects were assigned randomly to one of three groups" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | RCT with obvious control |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Only two subjects failed to complete the 12‐week experimental period, both in the social activity group" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: Canada Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease, MMSE less than 20, MMSE item 8 score of less than 3, ability to walk 5 metres with or without walking aid or supervision Exclusion criteria: medical: cardiac conditions precluding ambulation % Eligible within home: not reported Walk and talk group: N = 30; mean age = 83.23 years (SD 8.34); 16 women Talk‐only group: N = 30; mean age = 81.68 years (SD 7.36); 15 women Control group: N = 26; mean age = 79.78 years (SD 8.30); 8 women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to investigate the effects of a walking/talking programme on communication, ambulation, and level of function on people with Alzheimer's disease Number of experimental groups: 3 Exercise features: walking Non‐exercise features: talking Walk‐and‐talk group: to walk and talk as much as possible with rest as necessary (guided conversation), 30‐minute sessions, 5 sessions per week for 16 weeks, led by a research assistant Talk‐only group: guided conversation only, 30 minutes, 5 sessions per week for 16 weeks, led by a research assistant Control group: usual care | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: 2‐minute walk test (Cooper 1968; Cooper 1970) | |

| Notes | Funding: Alzheimer's Society of Canada | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Residents were assigned within each site to one of three groups using a table of random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Research assistants were blind to the group membership of the residents when completing the measures, but not to the study design |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Does not specifically report blinded assessment for this measurement. However, it does report 1 measure where they were not used, so assume blinded RAs used for measurement

|

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | The nurses caring for the residents completed the LPRS. They were not blind to group membership |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Losses from each group significantly different P = 0.01 (talk‐only = 5, control = 7, and talk‐and‐walk = 0) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Not all observed ADL measures (i.e. LPRS in this study) were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: Canada Consent: fully‐informed consent Inclusion criteria: ability to ambulate independently without walking aid, eyesight sufficiently good to read large new print, hearing sufficiently good to hear instructions in normal speaking voice, ability to understand instructions, and ability to participate in exercise programme Exclusion criteria: see inclusion criteria % Eligible within home: 69 Intervention: N = 25 | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to test the hypothesis that increase in postural sway is due to nervous system deterioration, and as a consequence, no improvement is possible – irreversible loss of function Number of experimental groups: 2 Exercise features: exercise class delivered by physiotherapists, activities conducted aim to improve breathing, single and double limb balance, co‐ordination, flexibility, antigravity strength, trunk and ankle strength, and promote general relaxation Control: usual care | |

| Outcomes | Balance: postural sway (measured on a force platform; lateral and anteroposterior sway measured with eyes open and eyes closed) | |

| Notes | Funding: Canadian Geriatrics Society | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Subjects were randomized into an exercise or control group using the Rand Corporation random tables" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No mention of blinding of participants, but usual care in same setting, so intervention would have been obvious |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 2 participants dropped out of the exercise group ‐ may be related to intervention, but less than 10% of group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: senior hostel residents ADL status details: not reported | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to evaluate the additional effect of functional exercises on balance and lower extremity function among hostel‐dwelling elderly people partaking in strength training Intervention: strength and balance group (N = 16) | |

| Outcomes | Physical function (other): functional test for physical performance (Guralnik 1994), Tinetti Mobility Scale (gait and balance) (Tinetti 1986) | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stated used random number table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Stated that all exercise sessions were undertaken by a single exercise trainer. As a result he/she would have been aware of group status |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Similar numbers lost for similar reasons |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT, repeated measures cross‐over design | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: unspecified Inclusion criteria: score of 25 to 40 points on the Paracheck Geriatric rating scale Exclusion criteria: see inclusion criteria % Eligible within home: not reported Group 1: N = 10 | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: (1) materials‐based intervention would elicit more repetitions and greater distance of movement than imagery‐based occupation and rote exercise; (2) imagery‐based occupation would elicit more repetitions and greater distance of movement during physical activity than rote exercise Number of experimental groups: 3 Exercise features: materials‐based occupation involved kicking a balloon; imagery‐based occupation involved kicking an imaginary balloon; rote exercise involved being asked to kick your foot as in a demonstration; participants were asked to kick with the same foot as many times as possible before becoming tired Group 1: materials‐based occupation, followed by imagery‐based occupation, followed by rote exercise | |

| Outcomes | Physical function (other): vertical kicking speed, vertical kicking distance | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Subjects were randomly assigned to three groups" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Cross‐over design ‐ all participants received all interventions ‐ it is likely that participants would have been able to tell which was the intervention under experiment and which was the control |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | Cross‐over design, but intervention unlikely to produce a carry‐over effect |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: ambulatory independent | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to compare the effectiveness of unsupervised home and supervised group exercise on parameters related to risk of falling among older adults Intervention: Supervised group exercise (SGE) group (N = 21) | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: TUG test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991) | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "...code number of each subject was written on a card and placed in an envelope, and the envelopes were then put in two groups by a person with no knowledge of the codes" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...code number of each subject was written on a card and placed in an envelope, and the envelopes were then put into two groups by a person with no knowledge of the codes" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Participants were in the same home; 1 group supervised, and 1 unsupervised so knowledge of allocation likely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The physiotherapist, who carried out all measurements, both at baseline and after the exercises, was also unaware of the group the subjects were in" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Slight imbalance in number of participants lost to follow up between groups (more in UHE group than in SGE group), although similar reasons across groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: frail, long‐term care facility residents, aged 75 years or older | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to examine the effects of structured strength and balance training in frail, elderly long‐term care residents Balance training (10 minutes): exercise balls, balance discs and blocks (20 cm high) used | |

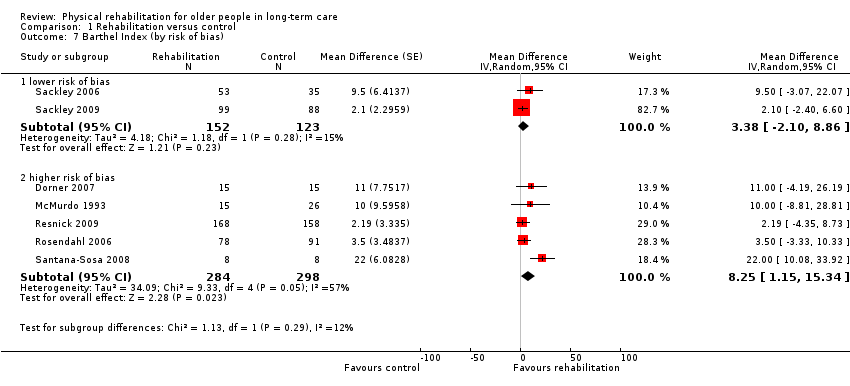

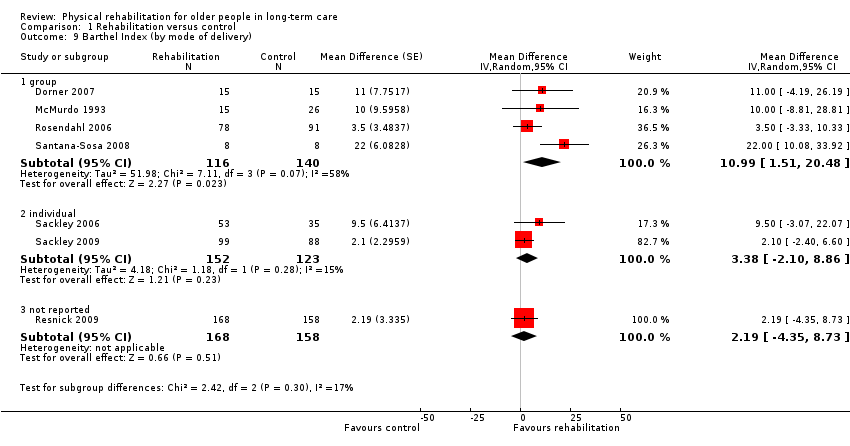

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: BI (0 to 100 scale), FIM | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Matched pairs "divided randomly" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No mention of blinding of participants, but RCT in same home and usual care as alternative |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Neither the psychologist nor the physiotherapist, who tested muscle function, were informed by the study organisers to which group participants were assigned. Unclear who assessed BI and FIM and if assessors were blinded to allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Same number of losses to follow‐up in each group, but unclear if reasons for losses to follow‐up were different between groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Country: the Netherlands Inclusion criteria: see exclusion criteria Exclusion criteria: cognitive: impaired cognition to the extent that they could not process information provided during the testing and exercising; medical = GP judged whether there was a medical contraindication to exercising; functional = unable to walk more than 6 metres independently (aids allowed) % Eligible within home: not reported Functional walking: N = 130 (7 residences); 80 allocated intervention, 50 allocated control In balance: N = 148 (8 residences); 94 allocated intervention, 54 allocated control | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to determine the effects of moderate intensity group‐exercise programme on falls, functional performance, and disability in older adults, and to investigate the effect of frailty on outcome Number of experimental groups: 4 All participants (including control) required to report levels of physical activity to monitor and control contamination from the intervention Interventions: 2 exercise programmes, both with evidence that they were effective in preventing falls, 1 session per week for 4 weeks followed by bi‐weekly sessions for 16 weeks, 90‐minute sessions including 30‐minute social element intended to increase motivation; all groups had their own instructor and assistant Functional walking: 10 exercises: balance, mobility, and transfer training | |

| Outcomes | Risk of falling: time to first fall | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported; no commercial party had any financial interests | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "The participating homes were randomly assigned to one of the two exercise intervention programs, using sealed envelopes. Participants in each of the homes were then randomly distributed across an intervention and a control group, using computer‐generated random numbers. The maximum size of the exercise group in each home was set at 12, with the provision that the control group should contain at least 5 participants" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "The participating homes were randomly assigned to one of the two exercise intervention programs, using sealed envelopes" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Quote: "The outcome of the randomization was notified to the participants in a letter after baseline assessment" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information ‐ no information included about who undertook the outcome measures |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information ‐ no information included about who undertook the outcome measures |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | ITT analysis stated. However, baseline figures do not match number of participants initially randomised. 6 participants excluded from analyses of fall data because there was no reliable data available; 30 participants excluded from analyses of physical function and disability data because of missing post‐intervention assessment (24 of whom had dropped out of the study). Reasons not given per group and unclear impact on outcomes |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT Baseline difference in strength: exercise + nutrition participants significantly weaker than exercise‐alone participants Losses to follow up: 3 lost from exercise‐only group (1 lack of interest, 1 musculoskeletal pain, 1 pneumonia), 2 from supplement‐only group (1 death, 1 lack of interest), and 1 lost from control group because of death | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: not specified Inclusion criteria: aged over 70 years, residential status, ability to walk 6 metres Exclusion criteria: cognitive = severe cognitive impairment; medical = rapidly progressive or terminal illness, acute illness, unstable chronic illness, myocardial infarction, fracture of a lower extremity within 6 months before the study, insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus, if they were on a weight loss diet or undergoing resistance training at the time of enrolment, if test of muscle strength revealed a musculoskeletal or cardiovascular abnormality % Eligible within home: 26.7 Exercise‐only group: N = 25; mean age = 86.2 years ± 1.0 mean SE; range = 72 to 95 years; 64% women Supplement‐only group: N = 24; mean age = 85.7 years ± 1.2 mean SE; range = 75 to 97 years; 71% women Exercise and supplement group: N = 25; mean age = 87.2 years ± 1.2 mean SE; range = 76 to 98 years; 64% women Control group: N = 26; mean age = 89.2 years ± 0.8 mean SE; range = 78 to 98 years; 54% women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: hypothesis: physical frailty is partially mediated by skeletal‐muscle disuse and marginal nutritional intake, and should therefore be reduced by interventions designed to reverse those deficits Number of experimental groups: 4 A therapeutic recreation specialist delivered the exercise components Exercise‐only group: high‐intensity progressive resistance training of the hip and knee extensors, commencing at 80% of 1 repetition max and progressing as able Supplement‐only group: 240 ml Exceed micronutrient supplement drink daily, representing 360 kilocalories, delivered in an unmarked container Exercise and supplement group: comprised both interventions Control group: 240 ml of a minimally nutritive liquid delivered in the same way, plus 3 activities of the participants' choice offered by the same service, but excluding resistance training | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: gait velocity over a 6.1 metre course (Fiatarone 1994) | |

| Notes | Funding: National institute of Ageing Agricultural Research Service Public Health Service of Hebrew Rehabilitation Centre, Massachusetts Brookdale Foundation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided on randomisation procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Study performed in one home. As a result, it would have been difficult to blind participants and would have been obvious which groups they were assigned to |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clear who performed mobility outcome assessments |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Outcome data missing for some participants because of technical problems or illness at time of testing |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Country: UK Consent: fully‐informed Inclusion criteria: > 70 years, mobile, able to participate in test battery, no medical conditions that would interfere with safety regarding training program Exclusion criteria: 6 participants were excluded, but no reasons given % Eligible within home: 76.9 Intervention group: N = 10; mean age = 88 ± 5 years; all women Control group: N = 10; mean age = 87 years ± 4 years; 9 women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: study question: is it possible to improve functional ability in older people by getting them to practise the functional tasks themselves? Number of experimental groups: 3 Exercise features: circuit of 8 functional exercises for 30 seconds initially progressing to a maximum of 1 minute, then increasing difficulty of task Control: reminiscence and recreational sessions; gentle, seated range of movement exercises (trunk and upper limbs only) Personnel delivering interventions not specified | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: stair ascent/descent, walking distance in 15 seconds | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | This was a cluster randomised trial. No evidence as to how randomisation was determined |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No evidence to demonstrate if individuals were recruited into the trial before/after the homes had been randomised to intervention or control |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No evidence of blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No evidence of blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Missing outcome data (5 dropouts; 4 from intervention) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | In the results, confidence intervals are only reported for some results (not clear why) |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: Canada Consent: assent accepted No participants were currently involved in any physical exercise programme or had any recent exercise history Inclusion criteria: ability to follow directions; ability to walk across a room (with or without assistive device); no recent history of cardiovascular, cerebral vascular, respiratory, systemic, muscular, or uncontrolled metabolic disease Exclusion criteria: see inclusion criteria % Eligible within home: not reported Control: N = 10; 75 to 87 years | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: examine the effect of an onsite and simple progressive lower body training programme designed to improve muscle power on functional abilities in frail older adults Number of experimental groups: 2 Exercise features: 10‐minute warm‐up and stretch, strengthening components utilised seated and standing components focusing in lower‐body muscle groups, Thera‐Bands® gradually introduced to increase resistance, number of exercise repetitions were gradually increased and a speed element introduced, 10‐minute cool‐down, personnel delivering interventions not specified Control: no active or placebo intervention, asked to perform no more or no less activity than normal on a daily basis | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: six‐metre walk (time), TUG test (modified to 8 feet) (Bassey 1992; Rikli 1999) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Subjects were randomly assigned in a lottery format" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | RCT with usual care control, so obvious group assignment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No report of blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Differential loss to follow up but seems unlikely to be related to intervention |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: assent accepted Inclusion criteria: > 65 years old, some deficits in self care – requiring assistance with dressing, grooming, and feeding Exclusion criteria: see inclusion criteria % Eligible within home: not reported | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to test the assumption that elderly individuals participating in a range of motion exercise programme will show more of an increase in self care in hygiene and eating than those who do not Exercise features: upper limb and lower limb range of movement exercises; personnel delivering the intervention were not described Control: movies only | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: Performance Test of Activities of Daily Living (PADL) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided on randomisation procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No mention of blinding of participants, but control group watched movies, and outcome measure was physical so intervention would have been obvious |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | No details provided |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | No information about losses to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Results for pre and post PADL not reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: elderly care‐home residents | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to assess the effectiveness of an activity programme in improving function, quality of life, and falls in older people in residential care | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: Late Life Function and Disability Instument (LLFDI) (Sayers 2004), TUG test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991), Elderly Mobility Scale (EMS) (Smith 1994) | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomised homes to the intervention or control group using computer generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...a biostatistician not involved in recruitment randomized homes to the intervention or control group..." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Cluster design so potential for blinding, but not specifically reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...research nurses blinded to the group allocation of the homes used standardised methods to assess outcomes..." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "...research nurses blinded to the group allocation of the homes used standardised methods to assess outcomes..." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Large losses, but balanced and similar reasons |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: fully‐informed consent Inclusion criteria: permission of participants' physicians was sought; no participants had any acute illness Exclusion criteria: see inclusion criteria % Eligible within home: not reported Intervention group: N = 12; mean age = 87 year; range = 72 to 101 years; 9 women Control group: N = 12; mean age = 82 years; range = 74 to 100 years; 9 women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: the programme addressed physical activity and psychosocial needs, such as learned helplessness and sadness, without placing additional strain on the hectic schedules of staff Number of experimental groups: 2 Exercise features: Control: participated in usual home activities, with opportunity to participate in sit and get fit programme after the study period | |

| Outcomes | Flexibility: ankle dorsiflexion and plantarflexion (range of motion), shoulder abduction, hip flexion and extension, elbow flexion and extension, shoulder anterior flexion, knee flexion (range of movement) | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided on randomisation procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No information provided, but RCT with obvious intervention/control |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No attrition |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Pre and post data not reported in an appropriate format (only reported as percentage change; no absolute figures) |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: not specified Inclusion criteria: Parachek score > 25 Exclusion criteria: see inclusion criteria % Eligible within home: not reported | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: tested the hypothesis that materials‐based occupation elicits a greater number of repetitions during physical activity in elderly persons than rote exercise Number of experimental groups: 3 Exercise features: materials‐based occupation (kicking balloon); imagery‐based occupation (kicking imaginary balloon); rote exercise (kicking foot as demonstrated) Group 1: materials‐based occupation, then imagery‐based occupation, then rote exercise Participants were instructed to kick as many times as possible and stop when too tired to continue All interventions were supervised by a research assistant, conducted in one‐off sessions, with 3 days in between each 1 | |

| Outcomes | Endurance (physical other): kicking repetitions | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Subjects were randomly assigned..." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Not addressed; all three groups received each intervention in different orders |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No incomplete outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | Cross‐over design, but intervention unlikely to produce a carry‐over effect |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: Canada Consent: assent accepted Inclusion criteria: able to stand with minimal assistance, ability to follow simple instructions Exclusion criteria: medical = recent cardiovascular event, vestibular disorder, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled epilepsy, fracture within 4 months, total blindness/deafness, surgery planned for within the next 4 months; functional = holidays planned for within the next 4 months, recent admission (less than 3 months) % Eligible within home: not reported FFLTC (functional fitness for long‐term care) group: N = 55; mean age = 79.7 years; 29 women ROM (range of motion) group: N = 41; mean age = 80.4 years; 30 women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: this study compared traditional range of motion to a 'functional fitness for long‐term care' programme designed to improve strength, balance, flexibility, gait, functional capacity, and strength Number of experimental groups: 2 Exercise features: ROM group: comprised seated exercise to improve range of movement (fingers, hands, arms, knees, ankles), relaxation, vocal exercise, and word/memory games Groups were of mixed ability, supervised by recreation staff | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: gait speed over 7 metres (self‐selected normal pace), gait speed over 7 metres (fast pace), TUG test (seconds) (Podsiadlo 1991), FIM | |

| Notes | Funding: grants from the Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute, The Walter J. Blackburn Family Foundation, The Richard Ivey Foundation, and the Ontario Ministry of Health Long‐term Care | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stated used a random number table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding attempted, but potential that blinding was broken as participants were from the same setting |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | TUG: stated research assistant blind to study condition |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | FIM: stated research assistant blind to study condition |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Much higher attrition rate in FFLTC than ROM, 19/55 (35%) versus 9/41 (22%), and large numbers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: nursing‐home residents Excluded: not reported | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to examine the effect of Tai Chi on health‐related quality of life in nursing‐home residents | |

| Outcomes | Balance: balance (Single Limb Stand Timed test) | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Author reports homes as randomised, but no information provided on randomisation procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Stated that the instructor was blind to outcome measures. However, participants could not have been |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Figures not provided for loss to follow up (hospitalisation, death, or move to other home) for intervention or control group (presented as combined data only) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Country: USA Consent: informed consent from participant or relative and from their doctor Inclusion criteria: nursing home long‐term care resident, physically capable of safe bilateral lower extremity weight‐bearing with supervision or minimal assistance, cognitively able to follow simple directions Exclusion criteria: cognitive = unable or generally unwilling to follow simple directions; medical = inability or medical restriction to bear weight on both lower extremities, less than 65 years of age; functional = participating in skilled rehabilitation (physical therapy or occupational therapy) immediately prior to study % Eligible within home: unclear Group breakdown: not given, 29 to 30 participants in each group | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: investigation of the effect of a standing exercise programme on the number of falls and the severity of intrinsic fall risk factors (functional losses of strength, balance and endurance, depression and number of infections) Number of experimental groups: 3 Intervention group: (group 1): comprised exercises in standing and walking activities, triggered when energetic music was played over intercom | |

| Outcomes | Falls: number of falls | |

| Notes | Funding: unclear | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Assignment to specific activities will be randomized by computer" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Blinding of participants would not have been possible ‐ participants would have been aware of which group they were in |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear if assessor was blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Author states that the 6 participants who were unable to complete the post‐tests were "dispersed among the groups, with reasons for dropping out unrelated to the intervention" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: RCT | |

| Participants | Characterisation: frail elderly women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to evaluate the effects of exercise therapy using the Takizawa Program | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: FIM | |

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided on randomisation procedure |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information provided |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | No report of blinding of participants, but usual care so intervention would have been obvious |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The evaluators of FIM in this study were the care workers who provided daily care to the patients, and were blind to the patient’s assignments to the Ex or Co group" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Slightly more losses to follow up in exercise group than in control group, although same reason provided across groups |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Country: Scotland, UK Consent: assent accepted Inclusion criteria: see exclusion criteria Exclusion criteria: cognitive: severe communication difficulties Residential homes all had identical entrance criteria, namely that residents should be able to toilet, dress, and walk independently % Eligible within home: not reported Intervention group: N = 20; mean age = 82.3 years (SD 6.9); 12 women Control group: N = 29; mean age = 79.3 years (SD 6.2); 21 women | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: to evaluate whether participation in regular exercise was acceptable to residents of old people's homes, and whether it produced significant improvements in balance, flexibility, strength, or functional capacity compared with a control group who participated in reminiscence sessions Number of experimental groups: 2 Exercise features: full upper limb and lower limb range of movement; seated exercises to music, intended to promote strengthening; exercise groups lasted for 45 minutes, and were conducted twice weekly for 7 months Control: music and reminiscence therapy designed to prompt social interaction | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: BI (0 to 20) | |

| Notes | Funding: The Mathew Trust The ICL Discretionary Trust | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation...prepared from a computer‐generated random numbers table" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was by opening sealed envelopes supplied in sequence by the study co‐ordinator" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | No report of blinding of participants ‐ although exercise groups and reminiscence groups were in different homes, so participants possibly weren't aware if they were intervention or control |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | All measurements made by the same observer that provided the interventions |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | More losses to follow up in exercise group (25%) than in control group (10%), and losses from exercise group include lack of interest |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol unavailable |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other apparent risks of bias |

| Methods | Design: cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Country: Scotland, UK Consent: assent accepted Inclusion criteria: volunteers were not excluded on the basis of any medical condition Exclusion criteria: cognitive = severe communication difficulties % Eligible within home: not reported Control group: N = 29; mean age = 82.0 years (9.6); 25 women Residential homes all had identical entrance criteria, namely that residents should be able to toilet, dress, and walk independently | |

| Interventions | Study aim or objective: (1) what are the mechanisms of improvement seen in McMurdo 1993?, (2) in the institutionalised elderly, does participation in regular seated exercise strengthen the quadriceps muscles?, (3) is participation in such exercise associated with improved psychomotor or cognitive function? Number of experimental groups: 2 Exercise features: performed seated exercise to music, number of repetitions and gravity‐resisted exercises were increased during the course of the study, group format, supervised by research physiotherapist Control group: reminiscence therapy designed to prompt social interaction and group discussion, 45 minutes in duration, conducted twice weekly for 6 months, facilitated by research physiotherapist | |

| Outcomes | Physical function in ADL: step test | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization...prepared from a computer‐generated random table" |