Intervenciones de entrenamiento para padres sobre el Trastorno de Hiperactividad y Déficit de Atención (THDA) en niños de cinco a 18 años de edad

References

Referencias de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión

Jump to:

Referencias de los estudios excluidos de esta revisión

Jump to:

Referencias adicionales

Jump to:

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by year of study]

Jump to:

| Methods | Design: Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Participants: The participating family had to have at least one child aged 6‐11 who satisfied the criteria for ADHD according to DSM III‐R criteria. Some children taking methylphenidate (investigators sought to balance numbers between groups). | |

| Interventions | Group treatment: 12 weekly two hour sessions in which eight families meet with two therapists. Two follow‐up sessions offered at three and six months after the last session, the topics of which are suggested by the parents. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: Parental Stress: Parenting Stress Index (PSI) (Abidin 1986). Mothers' results compared with fathers'. | |

| Notes | No figures given for outcomes. Only small, poor quality graphs shown for (1) Parenting Stress Index (2) Frequency of problem behaviours for mothers and fathers as function of treatment conditions and (3) Mother's problem solving performance. Consultation on issues related to the project was offered to teachers of participating children. This included "group presentations of the project material" or individual sessions. Topics included behaviour management, mediational communication, ADHD overview amongst others. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions: group treatment, individual treatment or waiting list control...A stratified sampling procedure is used so that the groups are balanced with respect to age of child, number of children who meet the criteria for ODD and the number of children who are taking Ritalin" (p71). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. Authors were contacted for clarification but no clarification received. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Cannot be blinded to the parent training intervention. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Cannot be blinded as they are delivering the parent training intervention. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | For the follow‐up evaluation session the "research assistant interviewing the mothers was blinded to the treatment status of the parent" (p. 80). |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | This paper presented preliminary findings, not all data had been analysed so not all outcomes had been addressed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Protocol for initial study not available. Not all data had been analysed at the time of publication. it is unclear why measures used at baseline (for example, Connors scales and the CBCL) are not used for programme evaluation. Furthermore, when outcomes of interest to the review are reported they are only done in graph format which are difficult to interpret, with only means and no standard deviations and no numerical data given in the text. Investigators also not that they did not evaluate fathers' data for Group treatment due to "large pre‐test differences...." |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess risk of other bias due to paper being a preliminary report. Data are presented only in graph form without exact figures, therefore it is difficult to interpret accurately. |

| Methods | Design: Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | Participants: Children aged 5‐9 with ADHD ‐ 77% with a firm diagnosis and the remainder 'had an average of six symptoms inattentive symptoms and seven hyperactive‐impulsive symptoms", for "at least six months" (p.13). ...'Majority '(p.15) of children 'were taking psychoactive medication for behavioral problems throughout the study'. Investigators interested in maternal stress and note at least half the mothers scored a standard deviation above the mean for non‐patient norms on the General Severity Index of the Symptoms Checklist 90‐Revised (SCL‐90‐R, Derogatis 1994). | |

| Interventions | Parent training group: 8 week manualised course focusing on teaching parents specialised child management techniques primarily involving contingency management (orientation, principles of behaviour management, parental attending to child behaviour, home token system, response cost, time out from reinforcement and child management in public areas). | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: Changes in the child's ADHD‐related behaviour ADDES‐Home (Hyperactive Impulsive Scale) (McCarney 1995) ADDES‐Home (Inatttentive Scale) (McCarney 1995) ADDES‐School (McCarney 1995) (Total scale; Inattentive and Hyper‐Impulsive scales Change in the child's ADHD‐symptom‐related behaviour in school setting Teacher ratings of child behavior of the school versions of instruments listed above Changes in general child behaviour The CBCL Total Problems Scale (Achenbach 1986) (measured by both parent and teacher) The CBCL Externalizing Scale (Achenbach 1986) (measured by both parent and teacher) The CBCL Internalizing Scale (Achenbach 1986) (measured by both parent and teacher) Secondary outcome: Parenting stress: The Revised Symptom Checklist (SCL‐90‐R) (Derogatis 1994). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote "mothers were ranked according to their GSI score on the SCL‐90‐R...were then separated into three groups based on their score and availability...each group was then randomly assigned parent training, parent training plus self management or waiting‐list control" (p. 23). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote "mothers were ranked according to their GSI score on the SCL‐90‐R...were then separated into three groups based on their score and availability...each group was then randomly assigned parent training, parent training and SM or waiting‐list control" (p. 23). |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Cannot be blinded to the parent training intervention. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Cannot be blinded as they are delivering the parent training intervention. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Research assistants analysing data were not blind to subject treatment conditions as they also provided child care if parents brought their children to sessions. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 54 mother‐child pairs originally, 6 were excluded because one parent did not complete the baseline assessment or attend any treatment sessions, five parents dropped out of the study and were unable or unwilling to complete post‐treatment assessments. Investigators did compare dropouts to those who attended and reported no significant differences between these groups and conducted separate MANOVA analyses including first only those who attended a majority of sessions and secondly , all participants regardless of attendance (which accounts for 55 of the initial 56 pairs). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Protocol for study unavailable. Repeated attempts to contact the author for this data were unsuccessful. Tables within dissertation do not report all means and standard deviations for all outcomes for all groups (for example, Table 19 does so only for three outcomes which are significant for one or both intervention groups). No data from teacher reports are mentioned at all beyond that 'findings were not significant' (pp 37‐8). |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to assess risk of other bias. |

| Methods | Design: Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Participants: 48 parents from families with children aged 6‐11 years, recently diagnosed with ADHD by a mental health professional according to DSM‐IV criteria. | |

| Interventions | Parent Training Groups: Based on the "Defiant Children" programme developed by Barkley (Barkley 1997). 10 x 2 hour structured sessions of parent training on a weekly basis for 9 weeks with a booster session 1 month after the 9th session. At each session new concepts and skills were introduced, parent handouts were reviewed, new parent behaviours were modelled, parents rehearsed new skills and the homework assignment was reviewed. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: Secondary outcomes: Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) (Johnston 1989). Parental level of stress Outcomes not used in this review | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "In order to divide the participants into two groups, each participant chose a group time that was convenient for them. The groups were then randomly assigned a letter either A or B. The participants in A were the experimental group (parent training programme) and the participants in B were the control group (parent support). There were two groups of each in order to keep the group sizes to a workable number and provide greater availability for participants" (p 42). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Precise method not stated. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Participants cannot be blinded to intervention. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Those delivering intervention cannot be blinded ‐ least of all in these conditions: "the same experimenter ran both the parent training and support groups." (p 83). |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Blinding of outcome assessors not mentioned and highly unlikely ‐ it would seem the investigator conducted her own assessments as well as having run both the structured treatment and the parent support group |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Initially 80 calls from parents, 68 accepted to begin programme, 61 parents began the study, 48 parents completed the programme. (Barkley group began with 27 participants, 23 completed; Support group started with 34 participants, 25 completed). Drop out reasons given as shifting work schedules, family crisis and non‐applicability of groups. Dropouts uneven between groups. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No obvious selective reporting but in the absence of a study protocol we cannot be clear. |

| Other bias | High risk | Investigator criticised her own design as follows: "A no contact group may be integrated in future research to be sure that the results were not due to just attention and/or contact with the participants ‐ statistically significant improvements in both the parent training and support groups for parents' sense of competence" (p 83) "The same experimenter ran both the parent training and support groups." (p 83) Large risk of contamination. "One parent in the support group had a friend in the parent training group which whom she compared notes." (p83). Investigator considers adding a confidentiality clause in future experiments. |

| Methods | Design: Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Participants: Children who met DSM‐IV criteria for ADHD (full scale IQ of the WISC‐III‐R for children under 6). | |

| Interventions | Behavioural Parent Training + Routine Clinical Care: Manual based parent training consisted of 12 x 120 minute group sessions over 5 months for 6 children's parents at a time. Sessions led by two psychologists, specific target behaviours were established for each child. Most techniques were drawn from Barkley (1987) and Forehand & McHahon (1981). Parenting skills addressed were: structuring the environment, setting rules, giving instructions, anticipating misbehaviors, communicating, reinforcing positive behaviour, ignoring, employing punishment, and implementing a token system. Psychoeducation and restructuring of parental cognitions were also important elements. Homework assignments were given and parents read chapters from a specially written book by van der Veen‐Mulders (2001). Each week parents practiced the skills and wrote reports after the exercises. Follow up assessment 25 weeks post‐intervention. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "randomized block design" (p.1265). No method specified. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Participants cannot be blinded to intervention. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Those delivering intervention cannot be blinded. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Unclear risk | Blinding of outcome assessors not mentioned. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Investigators described using intention‐to‐treat analysis for missing data (using a last‐observation‐carried‐forward method) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | All outcomes prospectively stated have been reported. However, they collected information from both parents separately but state that: "In this study we analyzed the data from the mothers" (p 1266). |

| Other bias | Low risk | Study appears to be free from other sources of bias. |

| Methods | Design: Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Participants: Participants were families of 62 children (42 boys) with ADHD. A comparison group of ‘normal’ children (62 age‐ and sex‐matched children) were also recruited. Diagnoses of those with ADHD were made via Child Symptom Inventory (CSI, Gadow 1994) and diagnoses were verified in a clinical review with parents using the K‐SAD (Kaufman 1997). Majority of children with ADHD were DSM‐IV Combined Type (ADHD‐C; n = 46) and the remainder were DSM‐IV Inattentive Type (ADHD‐I; n = 16). Data on ethnicity provided for the whole sample. Most children (85%) classed as white, 5% African American, 2% Asian American, 1% Latino and 7% of more than one race. Each child participated with one parent ‘most involved in a child’s social life’, 94% of whom were female. Children on medication (n = 40) for 3 months prior to study were permitted to continue on the same regime. Age: 6‐10 years (mean = 8.26, SD = 1.21). | |

| Interventions | Parental friendship coaching (PFC) was provided in eight 90 minute group sessions, delivered once weekly, involving 5 to 6 parents and led by two clinicians. The parent who had originally completed questionnaire and attended baseline playgroup assessment was requested to attend PFC, but other parent could attend if wished. Sessions were manualised. One month after the study ended, parents were contacted by phone and interviewed regarding changes in their child’s peer relationships. Topic I: Setting a foundation for effective coaching by improving the parent‐child relationship Homework issued with each session involving worksheets, practice sessions, discussions with the child and setting up playdates. Group viewing of videotapes of parental interaction was used as a teaching tool. Control group: No treatment, but after follow‐up, control group parents were offered a workshop summarising PFC content | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: Changes in general behaviour Social Skills Rating System (SSRS): (Gresham 1990) (as assessed separately by both parent and teacher) Change in the child's ADHD‐symptom‐related behaviour in school setting | |

| Notes | Funding from NIMH grant | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "randomly assigned to receive PFC or to be in a no‐treatment control group". Method of randomisation not described. It is clear that six cohorts were randomised in a stratified manner, each cohort containing five to six playgroups. Each playgroup contained one parent receiving PFC, one parent receiving no treatment, and two other parents of children without ADHD, who received no intervention. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Participants cannot be blinded to intervention. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Those delivering intervention cannot be blinded. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Blinding of outcome assessors was mentioned for those assessing videotaped interactions. Blinding is not mentioned for other outcomes, but it seems likely that this was attended to given the rigour relating to the videotaped outcomes. Also, "although parents were obviously aware of whether or not they had received PFC, study personnel kept teachers unaware of the family's treatment status and asked parents to not give teachers this information" (page 740) (Enders 2001). |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Investigators described using intention‐to‐treat analysis for missing data (p. 744) using "full information maximum likelihood methods". |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All likely outcomes appear to be reported but in the absence of the trial's protocol judgement must remain 'unclear'. |

| Other bias | Low risk | In one cohort, a parent of a child with ADHD (chosen randomly) was assigned to treatment. Steps were however taken to test no demographic differences existed at baseline between the two ADHD groups. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| RCT of children with ADHD. Three arms: methylphenidate plus psychosocial intervention versus methylphenidate alone versus methylphenidate plus attentional control. Excluded because psychosocial intervention involves social skills training involving direct intervention with the children | |

| RCT. Children diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorders, not ADHD | |

| Appeared to be RCT or at least quasi‐RCT of parent training versus wait list control for children diagnosed with DSM‐III‐R ADHD, based on parents' responses to interview questions; in fact, study not even quasi‐randomised (this was confirmed by personal contact with investigator) ‐ "subjects were in groups as a function of when they requested services" (Anastopoulous 2009) | |

| Uncontrolled intervention study ‐ participants were a convenience sample of four adolescents and families (part of Masters' thesis) | |

| Review article (focused moreover on disruptive behaviour disorders rather than ADHD) | |

| This three‐armed, apparently nonrandomised intervention study involves 'group mediation therapy' with three groups which appear to be clinically different from one another (those with clinically defined ADHD, those with borderline ADHD symptoms, and a 'norm group'). Triallists state that the study was not designed with a control group'. Furthermore, the nature of the intervention (mediation therapy) appears to involve direct work with children | |

| RCT of youths aged 12‐18 with ADHD. Three 'family' interventions were compared, none of which met inclusion criteria (interventions consisted of behavior management training; problem‐solving and communication training; structural family therapy) | |

| RCT of children with 'disruptive behaviour'; participants were too young or of insecure diagnosis (screening test involved parent report only) to be included within this review | |

| RCT of adolescents with ADHD. Both interventions were 'active' and involved family therapies, which involved both parents and direct work with adolescents, using Behaviour Management Training and Problems Solving Communication Training | |

| RCT of preschool children lacking formal a formal diagnosis of ADHD at entry into the trial. They were randomised to parent training, special kindergarten enrichment classroom only, the combined treatment condition and a no treatment condition | |

| RCT (conducted in course of a PhD). Age range problematic (3‐11) (separate data not available for children over 5, according to the author); also formal diagnosis of ADHD lacking in some participants | |

| RCT wherein children (only some of whom had a formal diagnosis of ADHD) were randomised to one of two active treatments, i.e., a 'Challenging Horizons Programme' plus 'Academic Skills Building Workshop' or 'Challenging Horizons Programme' only. This intervention does not meet inclusion criteria as direct interventions with the children were used and there is no no‐treatment control group | |

| RCT wherein participants were aged between 36 and 48 months and had no formal diagnosis of ADHD. Participants were randomised to enhanced behavioural family intervention, standard family behavioural intervention or wait list control group | |

| RCT of children with ADHD. Excluded because the intervention involved direct work with the children in both the “traditional parent training program” and the “STEPP” | |

| Intervention study involving children with ADHD using a BAB design to assess effects of delivery then withdrawal of a behavioural modification programme involving direct work with the children. No true control group | |

| RCT involving mothers of children with ADHD, a population known to be at risk of depression. The 'Coping With Depression Course' was not assessed to meet inclusion criteria for parent training. Child behaviour was, however, assessed, as well as maternal functioning, and ADHD‐related family impairment | |

| RCT of oppositional preschoolers to parent training or waitlist control. Excluded for both age and lack of ADHD diagnosis | |

| RCT of methylphenidate plus parent training versus methylphenidate plus parent support. No outcomes for children. Additional note: investigators confirmed PT and PS support, attendance was very low Schachar 1997 supplies additional information concerning this study | |

| RCT involving children diagnosed with ADHD DSM‐IV‐TR and aged between 5‐12 years old. Both interventions were active (parent training verus parent training combined with teacher support) this therefore does not meet inclusion criteria | |

| RCT wherein children with a 'younger cohort' of children (aged from 4 years up); not all diagnoses secure. Both active interventions involved direct work with children (child training alone was compared with parent plus child training). No parent training alone; no no‐treatment control | |

| Controlled (and possibly randomised) trial of children with "significant behavioural problems" but not necessarily an ADHD diagnosis, within an intervention or TAU group. The intervention group was flexible, involving a video‐modelling treatment including parent training but also direct work with children at times (thus not meeting this inclusion criterion as well) | |

| RCT of children aged 26‐72 months without formal diagnoses of ADHD, allocated to one of two active parent training groups which therefore does not meet inclusion criteria due to diagnosis, age and lack of eligible control group | |

| Uncontrolled intervention study of children with ODD and/or ADHD using a multiple baseline design | |

| Intervention study involving direct work with children without formal diagnosis of ADHD with children part of intervention | |

| This early paper (Dubey 1978) described "six clinical programs and one controlled, experimental program". The latter was a small RCT; however, participants had been recruited without a formal ADHD diagnosis, using only the Werry Weiss Peters scale, a screening measure with low sensitivity and lacking measures of impairment (regarded as insufficient for secure diagnosis (Daley 2009). Dubey 1983 reports on a subset of data from the original paper | |

| Not an intervention study but a study looking at parents of children with ADHD and considering parents' own ADHD symptoms in relation to their parenting practices | |

| Intervention study of children with ADHD plus CD or ADHD plus ODD involving combined modality treatment (parent training plus methylphenidate) which was not randomised or even quasi‐randomised (participants self selected into treatment and control groups) | |

| RCT of children with ADHD; participants were randomised to either parent training for fathers only or parent training plus sports activities for fathers and children. Although a de facto wait list control group was created, recruitment was not contemporaneous and therefore not part of the original randomisation (note: principal investigator noted with disappointment his ethics committee's refusal to allow him to create a contemporaneous no‐treatment control group) | |

| Not an intervention study but an investigation of the role of parental involvement in children's academic progress | |

| Controlled before and after intervention involving parents who chose (or chose not to) participate in a parenting programme whilst their children (diagnosed with a range of disruptive and emotional disorders but not necessarily ADHD) attended a health camp where a psychosocial intervention was delivered. This study is excluded both for reasons of sequence generation (self selection) and lack of adequate diagnosis | |

| RCT of children with conduct problems (mixed, not all with ADHD) with three active treatment arms, each a variant of a parenting programme ( no no‐treatment control group) | |

| RCT conducted in China of children with ADHD. Translation indicates that the intervention involved parent training in combination 'family meetings' (which appear to have involved a chance to share experiences and 'express emotions') as well as home visits during which clinicians engaged in direct work with the children. Study excluded because of direct work with the children | |

| Randomised study of parent training versus control; but participants had ODD or ADHD; subset data not available so excluded on the basis of no formal diagnosis of ADHD (author confirmed that separate data were not obtainable) | |

| RCT involving children with ADHD, excluded because of the three arms (child training only, child/parent training and child/parent training plus home/school‐based behavioural consultation) none involved an eligible 'no treatment' group | |

| Review article; not an intervention study | |

| An intervention study, but with no control group. Inclusion criteria "did not depend on meeting a defined threshold of symptom severity" but simply that a child over the age of three had an externalising problem | |

| RCT of 0.3mg/kg methylphenidate + parent training programme versus 0.3mg/kg methylphenidate + parent support group versus placebo + parent training programme versus placebo + parent support group. Participants were diagnosed with ADHD (DSM‐IV) based on rating scales completed by parents and teachers rather than clinicians and also slightly too young for inclusion within this review ‐ range 3.0‐5.9 years, mean = 4.77 | |

| RCT involving children ADHD comparing high and low doses of methylphenidate alone and in combination with behavioural parent plus child self control instruction. Study excluded because of direct work with children in parent training arm and lack of an adjunctive or no treatment arm | |

| RCT of children with formal diagnosis of ADHD; however, study lacks eligible control group. All interventions were 'active': participants were randomised either to a child group training or a parent training plus child training plus home and school training. This therefore does not meet inclusion criteria as there is no "no treatment control group" and both interventions involved direct work with children | |

| RCT of parent training group vs waiting list. Excluded due to children being underage (36‐48 months) and lacking secure diagnoses of ADHD | |

| RCT design acceptable; parent training programme and controls acceptable; outcomes acceptable. Diagnosis remained difficult to assess, even after personal communication with investigators and after reading multiple publications. According to an early publication, participants were "those who received a possible or definitive diagnosis of ODD and/or CD after assessment after all clinically referred children were first screened by means of the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI) using the 90th percentile as a cut‐off score according to Norwegian norms. Children who attained such a cut‐off score or higher were subsequently interviewed by one of three trained interviewers using the KIDDIE‐SADS" (Drugli, p 393). Subsequent contact with Dr Drugli suggested that subset ADHD children were similarly diagnosed (i.e. by trained interviewers but not specialists). In the paper published by Larsson et al (2008) authors report subset for "definitive" ADHD participants; but in the paper by Fossum et al (2008) authors admit as a limitation of the study that "the assessment of clinical levels of ADHD did not meet the formal criteria of a diagnosis." | |

| RCT with three arms of children with behavioural problems, a subset of whom had ADHD (data not reported separately). The trial compared parent training with parent training combined with behavioural training for children compared with a parent support group in which "emotional and social themes" identical to those in the other groups were discussed. After obtaining a partial translation of the paper we adjudged that the latter group was more than an 'attentional control' (as other similar groups had been constructed in other studies) in that a 'script' of behavioural issues, mapping on to the training in other groups, had been provided. ADHD was in addition not the focus of the study | |

| Three‐armed RCT focusing on very young children with a diagnosis of OCD. Participants were too young for this review: "Study participants were children ages 3.0–6.11 years and their parents" (average age 4.6 years, SD 1/4 1.0) | |

| RCT with three arms (enhanced self‐directed behavioural family intervention, a self help program and a waitlist control) for children with conduct problems (not ADHD specifically). Children were aged 2 to 6 years (mean 3.9) | |

| RCT of an early intervention group versus a community treatment group (which may have involved parent training). Child participants were aged 3 to 5 years and 'at risk' for ADHD, which does not meet inclusion criteria | |

| Study was quasi‐experimental and not randomised. A pharmacological intervention (methylphenidate) was compared to a psychosocial intervention (programme in the classroom ‐ excluded because intervention involved direct work with children without formal diagnosis of ADHD) versus a control group | |

| RCT. Participants (middle‐school children diagnosed with ADHD) were randomised to a 10 week programme or a community comparison. Intervention does not meet inclusion criteria as it involved direct work with the children | |

| RCT. Participants "diagnosed as having ADHD, identified in ADHD screening days" were randomised to parent training or medication group; does not meet intervention inclusion criteria as no comparison of parent training versus no parent training group | |

| RCT of Triple‐P Positive Training programme versus a waitlist control. Children involved may have had behavioural problems and outcomes included hyperactivity, but children did not necessarily have ADHD; entry criteria specified only that they be identified as "gifted" | |

| Complex large scale RCT; intervention included direct work with the children: "Behavioral treatment included parent training, child‐ focused treatment, and a school‐based intervention organized and integrated with the school year. The parent training, based on work by Barkley and Forehand and MacMahon,37 involved 27 group (6 families per group) and 8 individual sessions per family. It began weekly on randomization, concurrent with biweekly teacher consultation; both were tapered over time. The same therapist‐ consultant conducted parent training and teacher consultation, with each therapist‐consultant having a case‐ load of 12 families." (pp 1074‐1075) | |

| RCT involving children too young for inclusion in this review (aged 3 to 5 years) with behavioural disturbances were randomised to an intervention involving both parent training in behavioural management and direct work with children ('parent‐child interaction therapy' or PCIT), versus wait list control, compared with a 'nondisturbed' preschool sample | |

| RCT of PCIT (see above) where child participants had ODD with no diagnosis of ADHD and, as above, intervention involved direct work with children | |

| RCT in which participants were randomly assigned to a programme teaching parental behavioural management group or a control group. Children were included if they had extreme scores greater or equal to 15 on Connors teacher rating scale, which does not meet diagnosis inclusion criteria for ADHD | |

| RCT of what was described as a primarily "educational intervention" compared to a no treatment control group. Participants were mothers of children aged 5 to 11 years diagnosed with ADHD by an MDT evaluation. No child outcomes were measured, only those of the mother (knowledge of ADHD, willingness to have their child medicated and willingness to seek counselling, parenting sense of competence) were reported, which does not meet inclusion criteria | |

| RCT of eligible parent training intervention versus control; however, participants included parents of children aged between 3‐6 years without formal ADHD diagnosis (diagnosis made by parent structured screening interview by PhD psychologist) which does not meet inclusion criteria (Pisterman 1992b reports follow‐up) | |

| RCT of eligible parent training intervention versus control; however, participants included parents of children aged between 46.42‐52.41 months, and again without formal ADHD diagnosis (diagnosis made by parent or teacher on SNAP checklist (Pelham 1982) which does not meet inclusion criteria (Pisterman 1992b reports follow‐up) | |

| Pre‐post design of both methylphenidate and parent training on the behaviour of three 'hyperkinetic boys' | |

| Not a randomised controlled trial. Review article | |

| Controlled study, but neither randomised or quasi‐randomised, comparing parent training plus medication (methylphenidate) plus consultation versus medication plus consultation alone for parents of children with ADHD. Excluded because participants chose their intervention groups themselves | |

| RCT. Participants were randomised to enhanced behavioural family intervention, standard behavioural family intervention, self‐directed behavioural family intervention or wait list control. Participants had no formal diagnosis of ADHD. Participants were aged 3 years old (between 36 and 48 months ‐ mean age was 3.39yrs) which does not meet inclusion criteria. McLennan 2001 summarises results of this study | |

| RCT. Participants were randomly assigned to a behavioural family intervention or cognitive behavioural family intervention which does not meet inclusion criteria as there is no eligible control group. Participants had no formal ADHD diagnosis, only 2 children had ADHD based on a structured interview with the mother using DSM‐IV criteria. Participants were aged 3‐9 years (mean = 4.39) which does not meet inclusion criteria | |

| RCT of parent training versus no treatment control. Focus of study was not ADHD, but disruptive behaviour in children with tics. Investigators recruited children with comorbid tic and disruptive behaviour disorders from a specialised tic disorders clinic. They specifically excluded children with ADHD not receiving medication. This yielded a subset of children with comorbid, medicated ADHD. | |

| Not a randomised controlled trial (although indexed in MEDLINE as such). Observational study investigated how co‐parenting affected children's externalizing behaviour and attempts at "effortful control", as rated by children's teachers and mothers | |

| Multicentre RCT involving parenting groups for children who were recruited for antisocial behaviour rather than ADHD. "Eligible children were all those aged 3‐8 years who were referred for antisocial behaviour to their local multidisciplinary child and adolescent mental health service" (p 2). From the text, it would appear investigators strenuously sought to exclude ADHD, as they listed as exclusion criteria for their trial: "clinically apparent major developmental delay, hyperkinetic syndrome [ICD‐10 criteria for inclusion within this review] or any other condition requiring separate treatment". ADHD is not mentioned in the published study. Personal contact with the author (Scott 2011) concerning a different study (Scott 2010) led to a disclosure that approximately half the study's participants subsequently proved to meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD (although the age of such children remains unclear) and data were generously provided. However, due to concerns that because ADHD was far from being the focus of this study (wherein recruitment included only aggressive children and [initially at least] attempted to excluded any child with a diagnosis or treatment for ADHD), we decided these data do not meet inclusion criteria | |

| RCT involving a mixed intervention programme including aspects of Webster‐Stratton's Incredible Years and aspects of the SPOKES projects in which parents read with their children, to promote literacy. Participants (all aged 6 years) were screened for a range of risk factors for antisocial behaviour, low reading ability, conduct problems and 'ADHD symptoms' via the PACS. Thus, a true diagnosis for ADHD of children was not made (nor was it the focus of the intervention) | |

| RCT wherein participants were randomised to parent training, parent counselling and support or wait list control. Children were 3 years old, which does not meet inclusion criteria. Participants had no formal diagnosis of ADHD, diagnoses was based on scores on WWP and PACS, which does not meet inclusion criteria. No child outcomes, which does not meet inclusion criteria. Baldwin 2001 summarises aspects of this study and Sonuga Barke 2002 provides additional data | |

| RCT wherein participants were randomised to parent training or wait list control. Children were 3 years old, which does not meet inclusion criteria. Participants were diagnosed with 'preschool ADHD' which does not meet inclusion criteria | |

| RCT with three active intervention arms, all involving direct work with the child. Age range and diagnosis of ADHD acceptable | |

| Controlled but not randomised nor quasi‐randomised study comparing Webster‐Stratton's Parents and Children Series parenting groups, the eclectic approach treatment or wait list control. Allocation not randomised, investigators wrote, in order "to allow urgent families, and families who had already waited a long time for treatment, to remain in the study". Children had behavioural issues but not necessarily a diagnosis of ADHD, aged 3‐8 years old. | |

| RCT focused on parental stress alone, in which participants were randomly assigned to parent stress management training or wait list control. Children were diagnosed with DSM‐IV ADHD. Children were aged 6‐15 years. No outcomes involved children. Outcomes measured included only Parenting Stress Index (PSI) (Abidin 1995) Parent Scale (Arnold 1993), Parental Locus of Control Scale (PLOC) (Campis 1986) | |

| RCT wherein participants with ADHD were randomised to methylphenidate or methylphenidate plus behaviour therapy. There was a direct clinical intervention involving the children: "The multimodal behavior therapy integrated family based and school‐based interventions with cognitive behavior therapy of the child" (p 50) | |

| Cluster RCT targeting disruptive children. Diagnosis of ADHD was unclear for all children and all active interventions ('universal' school wide intervention; targeted school intervention; targeted home intervention; control group) involved direct work with the child | |

| Single group intervention study (pre‐post test measures) of parent training for parents of children with ADHD. No control group | |

| RCT in which participants (mean age 7.41, of whom only a portion had a secure ADHD diagnosis) were randomly assigned to a treatment or a control group, however the intervention (which focused on improving communication between parents, teachers and primary care providers) and did not meet inclusion criteria as the treatment group did not consist of true parent training |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 1 Child's ADHD behaviour (home setting) CPRS‐R:S Show forest plot | 1 | 96 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐2.50, 3.10] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 1 1 Child's ADHD behaviour (home setting) CPRS‐R:S. | ||||

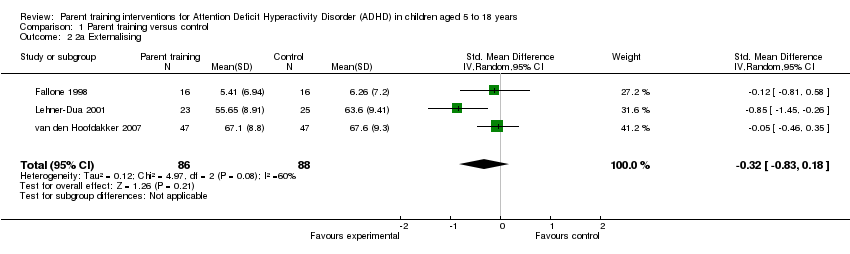

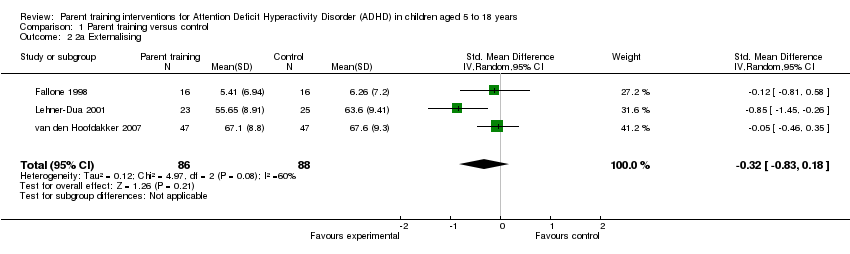

| 2 2a Externalising Show forest plot | 3 | 174 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.32 [‐0.83, 0.18] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 2 2a Externalising. | ||||

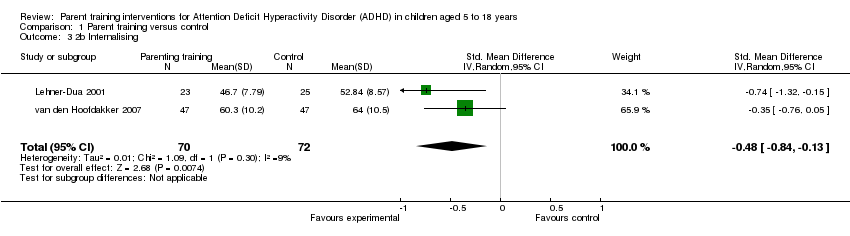

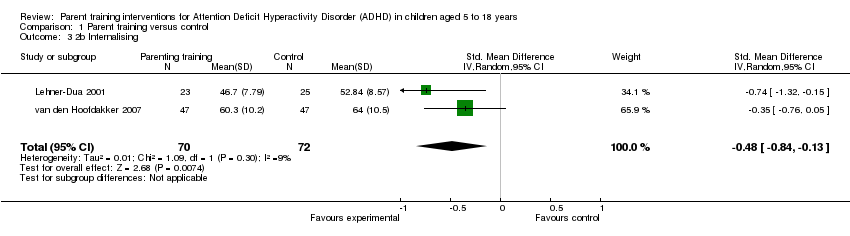

| 3 2b Internalising Show forest plot | 2 | 142 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.48 [‐0.84, ‐0.13] |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 3 2b Internalising. | ||||

| 4 7 Parenting stress ‐ PSI ‐ parent domain Show forest plot | 2 | 142 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.54 [‐24.38, 9.30] |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 4 7 Parenting stress ‐ PSI ‐ parent domain. | ||||

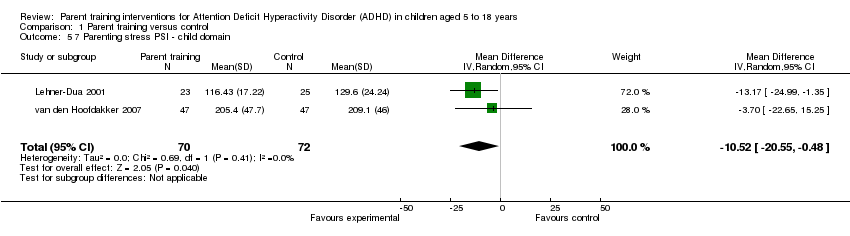

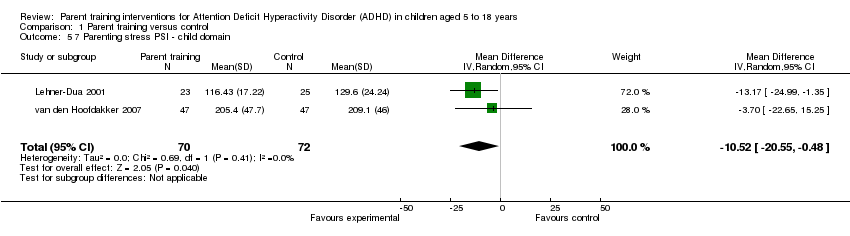

| 5 7 Parenting stress PSI ‐ child domain Show forest plot | 2 | 142 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.52 [‐20.55, ‐0.48] |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 5 7 Parenting stress PSI ‐ child domain. | ||||

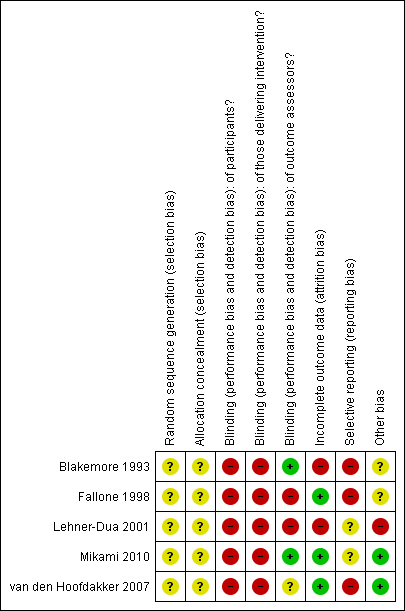

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 1 1 Child's ADHD behaviour (home setting) CPRS‐R:S.

Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 2 2a Externalising.

Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 3 2b Internalising.

Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 4 7 Parenting stress ‐ PSI ‐ parent domain.

Comparison 1 Parent training versus control, Outcome 5 7 Parenting stress PSI ‐ child domain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 1 Child's ADHD behaviour (home setting) CPRS‐R:S Show forest plot | 1 | 96 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐2.50, 3.10] |

| 2 2a Externalising Show forest plot | 3 | 174 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.32 [‐0.83, 0.18] |

| 3 2b Internalising Show forest plot | 2 | 142 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.48 [‐0.84, ‐0.13] |

| 4 7 Parenting stress ‐ PSI ‐ parent domain Show forest plot | 2 | 142 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐7.54 [‐24.38, 9.30] |

| 5 7 Parenting stress PSI ‐ child domain Show forest plot | 2 | 142 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.52 [‐20.55, ‐0.48] |