Orthophonie dans l'aphasie suite à un AVC

Résumé scientifique

Contexte

L'aphasie est un trouble du langage acquis suite à des lésions cérébrales touchant certaines ou l'ensemble des modalités du langage : l'expression et la compréhension orale, la lecture et l'écriture. Environ un tiers des personnes ayant subi un AVC présentent une aphasie.

Objectifs

Évaluer l'efficacité de l'orthophonie pour le traitement de l'aphasie suite à un AVC.

Stratégie de recherche documentaire

Nous avons effectué des recherches dans le registre des essais du groupe Cochrane sur les accidents vasculaires cérébraux (dernière recherche effectuée en juin 2011), MEDLINE (de 1966 à juillet 2011) et CINAHL (de 1982 à juillet 2011). Afin d'identifier d'autres essais publiés, non publiés et en cours, nous avons effectué des recherches manuelles dans le International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders (de 1969 à 2005) et les listes bibliographiques des articles pertinents. Nous avons également contacté les institutions académiques et d'autres chercheurs. Il n'y avait aucune restriction concernant la langue.

Critères de sélection

Des essais contrôlés randomisés (ECR) comparant l'orthophonie (intervention formelle visant à améliorer les capacités linguistiques et de communication, l'activité et la participation) à (1) l'absence de traitement orthophonique ; (2) une prise en charge sociale ou une stimulation (intervention assurant une prise en charge sociale et une stimulation de la communication, mais qui exclut toute intervention thérapeutique ciblée) ; et (3) une autre intervention orthophonique (différente en termes de durée, d'intensité, de fréquence, de méthodologie d'intervention ou d'approche théorique).

Recueil et analyse des données

Nous avons indépendamment extrait des données et évalué la qualité méthodologique des essais inclus. Nous avons contacté des investigateurs afin d'obtenir des données manquantes.

Résultats principaux

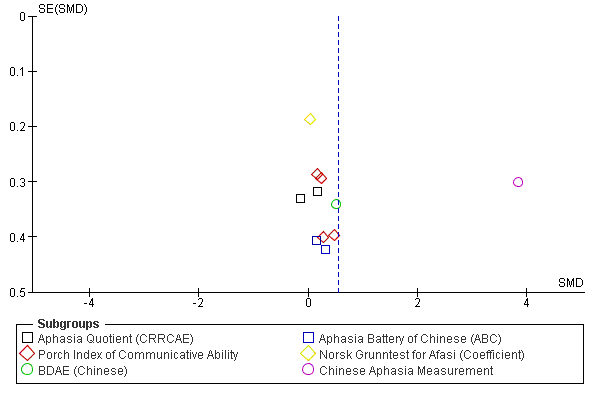

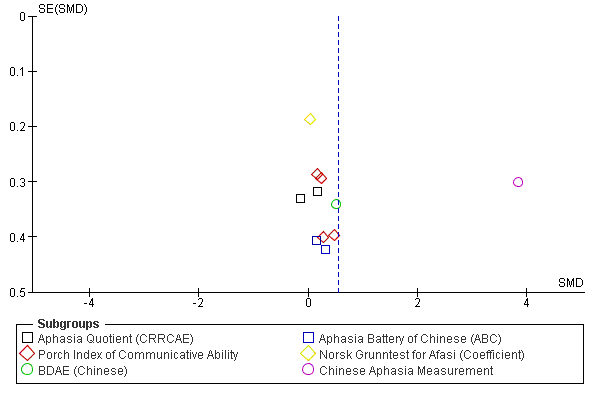

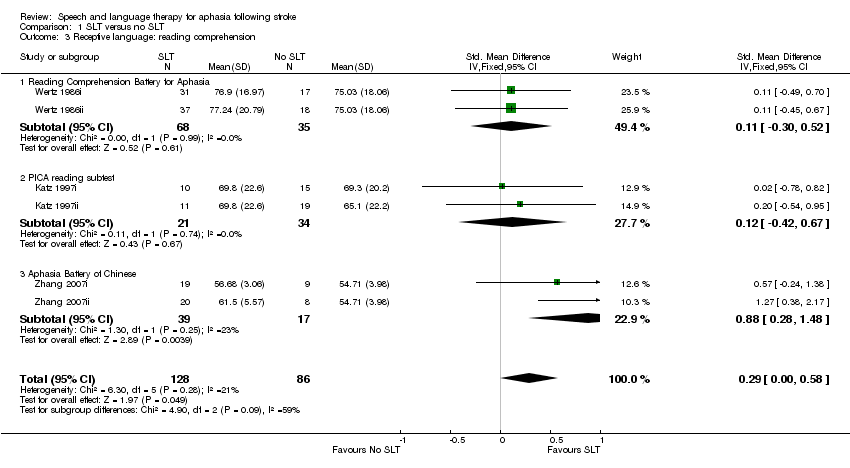

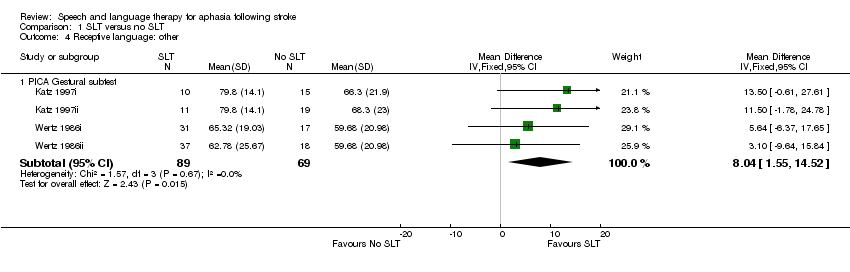

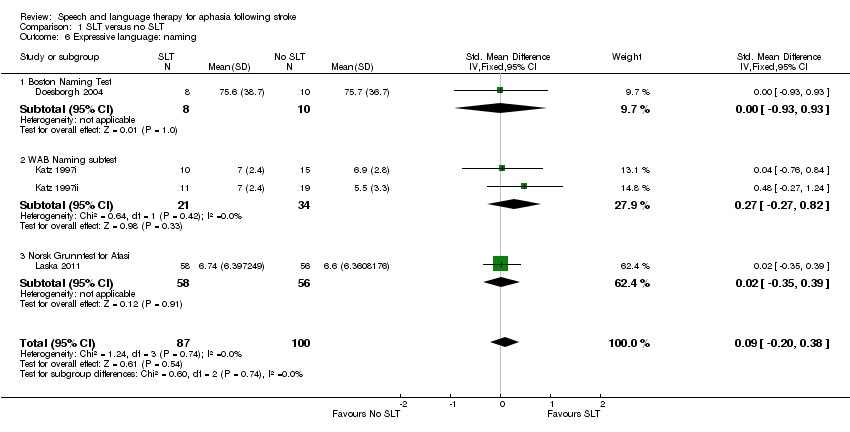

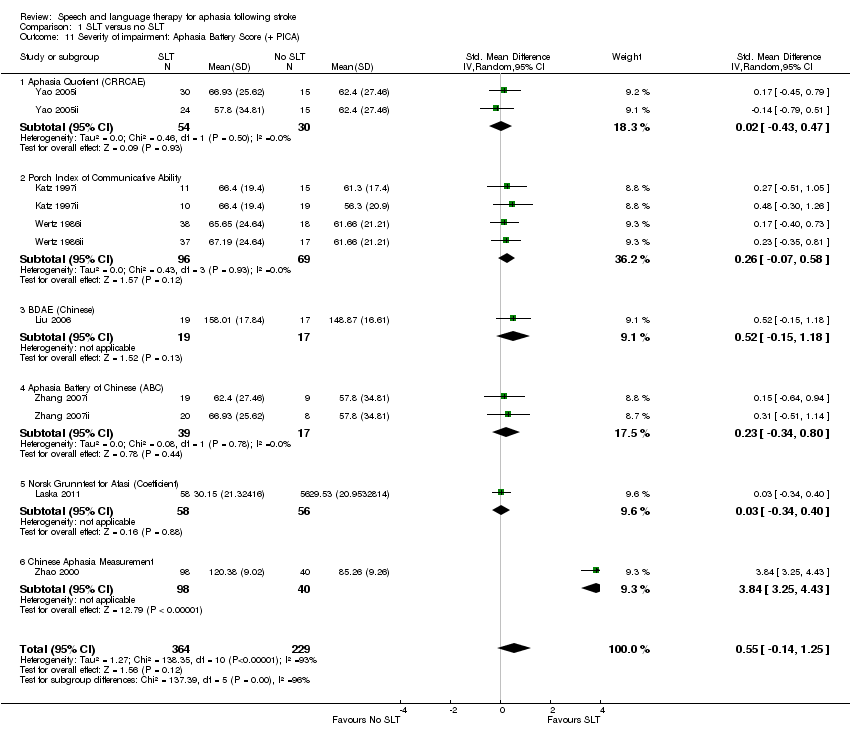

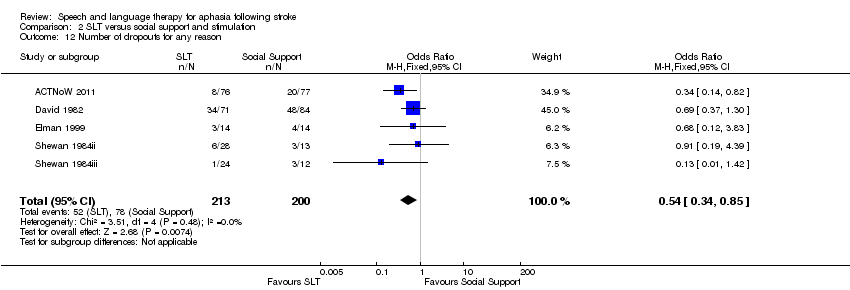

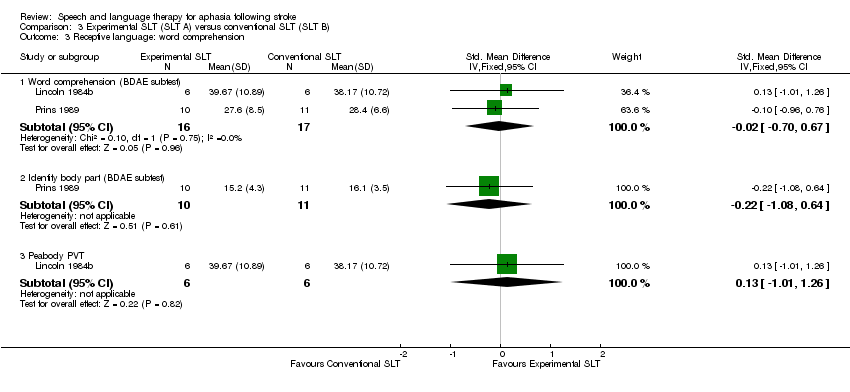

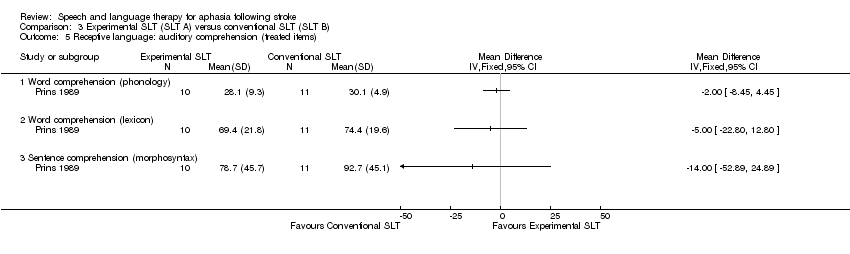

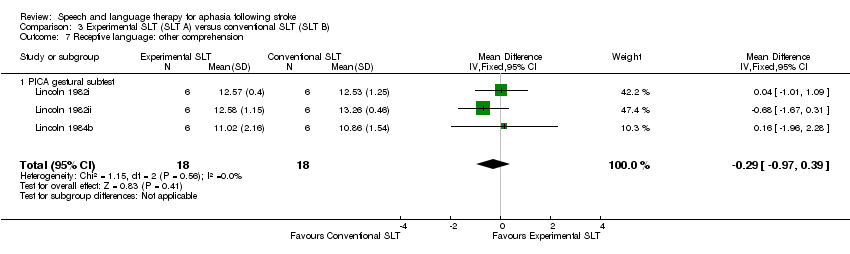

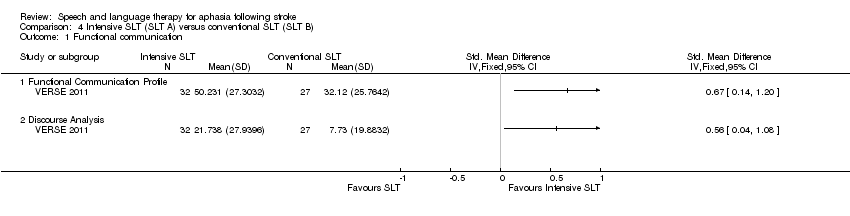

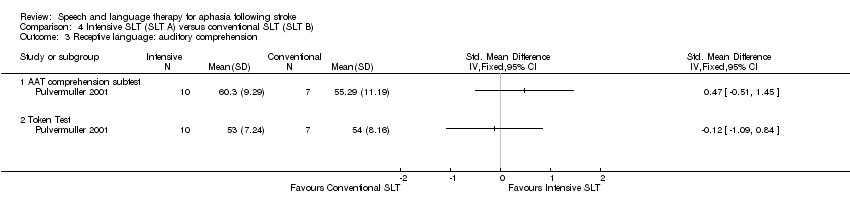

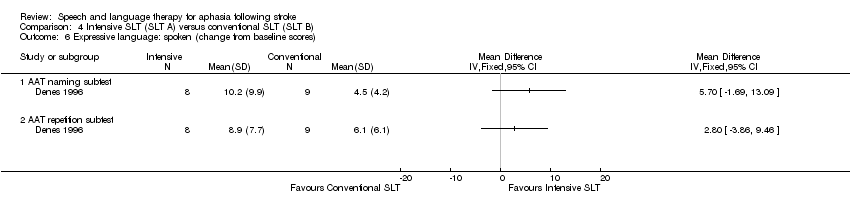

Nous avons inclus 39 ECR (51 comparaisons randomisées) impliquant 2 518 participants dans cette revue. Dix‐neuf comparaisons randomisées (1 414 participants) comparaient l'orthophonie à l'absence de traitement orthophonique dans lesquelles l'orthophonie présentait des effets bénéfiques significatifs au niveau de la communication fonctionnelle du patient (différence moyenne standardisée (DMS) 0,30, IC à 95 % 0,08 à 0,52, P = 0,008) et du langage réceptif et expressif. Sept comparaisons randomisées (432 participants) comparaient l'orthophonie à une prise en charge sociale et à une stimulation, mais n'ont identifié aucune preuve de différence au niveau de la communication fonctionnelle. Vingt‐cinq comparaisons randomisées (910 participants) comparaient deux approches à l'orthophonie. Il n'y avait aucune différence au niveau de la communication fonctionnelle. En général, les essais randomisaient un nombre réduit de participants parmi un éventail de caractéristiques (âge, période depuis l'AVC et profils de gravité), d'interventions et de résultats. Des données statistiques adéquates n'étaient pas disponibles pour plusieurs mesures.

Conclusions des auteurs

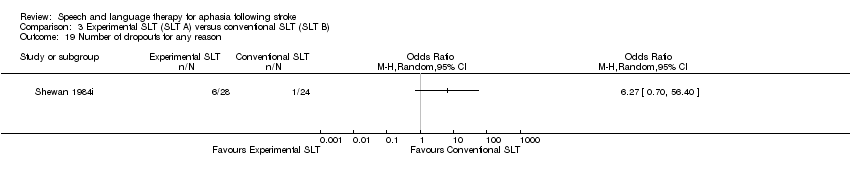

Notre revue fournit quelques preuves concernant l'efficacité de l'orthophonie chez les personnes aphasiques suite à un AVC au niveau de la communication fonctionnelle améliorée, du langage réceptif et expressif. Toutefois, la notification de certains essais était médiocre. Les effets bénéfiques potentiels d'un traitement orthophonique intensif par rapport à un traitement orthophonique standard étaient biaisés en raison d'un nombre de sorties d'études significativement supérieures dans le cas d'un traitement orthophonique intensif. Davantage de participants se sont également retirés de la prise en charge sociale par rapport à ceux soumis à des interventions orthophoniques. Les preuves étaient insuffisantes pour tirer des conclusions concernant l'efficacité d'une approche orthophonique spécifique par rapport à une autre.

PICOs

Résumé simplifié

Orthophonie dans l'aphasie suite à un AVC

L'aphasie (ou dysphasie) correspond à des troubles du langage survenant suite à un AVC. Environ un tiers des personnes ayant subi un AVC présentent une aphasie qui peut toucher un ou plusieurs aspects de la communication (parole, compréhension orale, lecture et écriture). Les orthophonistes évaluent, diagnostiquent et traitent l'aphasie à des stades divers et travaillent en étroite collaboration avec la personne aphasique et ses soignants. Il n'existe aucun traitement universellement accepté pouvant être prescrit à chaque personne aphasique. Nous avons identifié 39 essais impliquant 2 518 participants randomisés pouvant être inclus dans cette revue. Dans l'ensemble, cette revue contient des preuves issues d'essais randomisés suggérant que l'orthophonie peut avoir des effets bénéfiques, mais ces preuves étaient insuffisantes quant à la meilleure approche à adopter pour un traitement orthophonique.

Authors' conclusions

Background

Description of the condition

The term aphasia (less commonly referred to as dysphasia) is used to describe an acquired loss or impairment of the language system following brain damage (Benson 1996). Usually associated specifically with language problems arising following a stroke, it excludes other communication difficulties attributed to sensory loss, confusion, dementia or speech difficulties due to muscular weakness or dysfunction such as dysarthria. The most common cause of aphasia is a stroke (or cerebrovascular accident), mainly to the left hemisphere, where the language function of the brain is usually situated for right‐handed people. About one‐third of all people who experience a stroke develop aphasia (Engelter 2006; Laska 2001). The aphasic population is heterogeneous, with individual profiles of language impairment varying in terms of severity and degree of involvement across the modalities of language processing, including the expression and comprehension of speech, reading, writing and gesture (Code 2003; Parr 1997). Variation in the severity of expressive impairments, for example, may range from the individual experiencing occasional word‐finding difficulties to having no effective means of communication. The severity of aphasia can also change over time as one area of language difficulty may improve while others remain impaired. The impact and the consequential implications of having aphasia for the individuals themselves, their families and society highlight the importance of the effective management and rehabilitation of language difficulties caused by aphasia.

Description of the intervention

The primary aim of speech and language therapy (SLT*) in aphasia management and rehabilitation is to maximise individuals' ability to communicate. Speech and language therapists are typically responsible for the assessment, diagnosis and, where appropriate, rehabilitation of aphasia arising as a result of stroke. The ability to successfully communicate a message via spoken, written or non‐verbal modalities (or a combination of these) within day‐to‐day interactions is known as functional communication. Recent developments have seen speech and language therapists working closely with the person with aphasia, and in partnership with their families and carers, to maximise the individual's functional communication.

* For the purposes of clarity within this review we have reserved the abbreviation of SLT for speech and language therapy alone.

Why it is important to do this review

There is no universally accepted treatment that can be applied to every patient with aphasia and typically therapists select from a variety of methods to manage and facilitate rehabilitation including, for example, impairment‐based therapy and social participation approaches. We undertook this review update to incorporate new evidence, new systematic review methodologies and to reflect recent developments in clinical practice. A summary of the differences between this version and the original 1999 review is presented below.

Amendments to the original 1999 review

Following close inspection of the original review (Greener 1999) and detailed discussion among this review team, we made adjustments to the review, many of which reflect changes in Cochrane procedures, review methodologies, and style and structure in the time since the publication of the original review. These amendments were ratified by the Cochrane Stroke Group Editorial Board on 23 November 2006.

Background

We updated the Background section to include a definition of SLT and aphasia, and to reflect current approaches and rationale to SLT interventions and outcomes.

Objectives

We amended the Objectives to a single statement according to the standard format of Cochrane reviews; that is, to examine the effectiveness of SLT interventions for aphasia following stroke.

Types of studies

It was unclear whether or not quasi‐randomised controlled trials were included in the original review. We have excluded quasi‐randomised trials.

Types of interventions

We compressed the Types of interventions into three broad categories: SLT versus no SLT intervention, SLT versus social support or stimulation, and SLT intervention A versus SLT intervention B (where A and B refer to two different types of therapeutic interventions or approaches).

Types of outcome measures

We refined the Types of outcome measures to a single primary outcome measure of functional communication. Secondary outcomes include other measures of communication (receptive or expressive language, or both), psychosocial outcomes, patient satisfaction with the intervention, number of participant dropouts for any reason, non‐compliance with the allocated intervention, economic outcomes (such as cost to the patient, carers, families, health service and society) and carer or family satisfaction. Data relating to death, morbidity and cognitive skills were extracted in the original review but, on reflection, we did not consider these to be relevant indicators of the effectiveness of a SLT intervention and we therefore excluded them from this update. The original review reported overall functional status (e.g. Barthel Index) as one of a number of primary outcomes. As described above, we focused on a single primary outcome (in line with the current review methodology).

Data extraction tool

We could not obtain the original data extraction tool, therefore two of the review authors (HK and MB) created and piloted a new one before use.

Search methods for identification of studies

Re‐running the original search strategy for the MEDLINE and CINAHL databases raised over 12.6 million references. Therefore, Brenda Thomas, the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator, devised up‐to‐date search strategies. The International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders (previously named the British Journal of Disorders of Communication, the European Journal of Disorders of Communication and the International Journal of Disorders of Communication) was handsearched from 1969 to 2005. This journal has been indexed by MEDLINE since 2006 and was thus included in our electronic searches from this date.

Description of studies

The original 1999 review listed studies other than identified RCTs in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, including single case or case series studies. As there are a vast number of such studies, the updated table now only presents potentially relevant studies that appear to be randomised but which we excluded for other reasons (e.g. quasi‐randomised or where aphasia‐specific data could not be extracted).

Comparisons

Mid‐trial outcome scores were included in the original review. We have focused our reporting on post‐intervention and follow‐up scores. We have not included analysis of the number of participants who deteriorated on particular outcome measures.

Other amendments

As we were unable to obtain the extraction sheets for the trials included in the original review, we cross‐checked the data extracted for the original review with the available published and unpublished data. We made some amendments, including exclusion of some studies and categorising the methods of allocation concealment used in the included trials.

In this review update we took the decision to exclude quasi‐randomised studies and so one study, included in the original review, has been excluded from this review update (Hartman 1987).

After reviewing the data from another trial (Kinsey 1986), we decided that the reported comparison was not a therapy intervention as such, but rather a comparison of task performance (computer‐based or with a therapist). We thus excluded this trial from the review update.

The allocation concealment for one study (MacKay 1988) was considered 'inadequate' in the original review. We failed to get confirmation of the method of allocation from the authors and therefore we amended the allocation for this trial to 'unclear'.

The original review included a matched control group of no SLT intervention for one trial (Prins 1989). However, unlike the other groups in this trial, this group was not randomised, therefore we have excluded it from this update.

Another study (Shewan 1984) had been excluded from the original review on the grounds that it was not a RCT. Discussion with the trialists has since revealed that it was a RCT randomised controlled trial, and we have now included it in the review.

The original 1999 review included outcomes relating to the impact of SLT on the emotional well‐being of family members (Lincoln 1984a). We do not feel that such outcomes directly relate to the aims of this review and so we have not included these measures.

Information added to the 1999 review

Following an extensive search up to April 2009, we identified an additional 20 trials as suitable for inclusion in the review. The 2010 review included data from 30 trials involving 1840 randomised participants (Kelly 2010).

Information added to the 2010 review

Following an extensive search from inception of the electronic databases up to July 2011 we identified an additional nine trials eligible for inclusion in the review. This 2011 review update now includes data from 39 trials involving 2518 randomised participants.

Objectives

To examine the effectiveness of SLT for aphasia after stroke and in particular if:

-

SLT is more effective than no SLT;

-

SLT is more effective than social support and stimulation;

-

one SLT intervention (SLT A) is more effective than another SLT intervention (SLT B).

SLT intervention A or B refers to variations in intervention that differ in duration, intensity, frequency, method or in the theoretical basis of the approach to the intervention (e.g. cognitive neurological‐ versus psychosocial‐based interventions).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs that evaluated (one or more) interventions designed to improve language or communication. We included trials that recruited participants with mixed aetiologies or impairments provided it was possible to extract the data specific to individuals with post‐stroke aphasia. We did not employ any language restriction.

Types of participants

Adults who had acquired aphasia as a result of a stroke.

Types of interventions

We compressed the groupings presented in the original review into three broad groups for this review update. We have included trials that reported a comparison between a group that received a SLT intervention designed to have an impact on communication and a group that received:

-

no SLT intervention; or

-

social support and stimulation; or

-

an alternative SLT intervention.

SLT

We considered SLT interventions to be any form of targeted practice tasks or methodologies with the aim of improving language or communication abilities. These are typically delivered by speech and language therapists. In the UK, 'speech and language therapist' is a protected professional title and refers to individuals holding a professional qualification recognised by the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists and registered with the Health Professions Council, UK. For the purposes of this review we have extended this definition to include therapists belonging to a body of similar professional standing elsewhere in the world.

We are aware that the SLT profession does not exist in many countries and so in trials conducted in such settings where other clinical staff (e.g. medical or nursing staff) led targeted interventions that aimed to improve participants' communicative functioning we have included these interventions within this review as SLT interventions. We planned a sensitivity analysis of the impact of professional SLT training on the provision of an intervention where data allowed.

We also recognise that current rehabilitation practice may include SLT interventions that aim to improve communicative functioning but are delivered by non‐therapists (family members, SLT assistants, SLT students, voluntary support groups). Where those delivering the intervention have received training from a speech and language therapist and deliver an intervention designed by a speech and language therapist, we have described these as volunteer‐facilitated SLT interventions.

Social support and stimulation

Social support and stimulation refers to an intervention that provides social support or stimulation but does not include targeted therapeutic interventions that aim to resolve participants' expressive or receptive speech and language impairments. Interventions in this category might include, for example, emotional, psychological or creative interventions (such as art, dance or music) as delivered by other healthcare professionals (e.g. art, physical or music therapists). Other social stimulation interventions, such as conversation or other informal, unstructured communicative interactions are also included in this category.

We did not include pharmacological interventions for aphasia as they are addressed within a separate review (Greener 2001). In this 2011 review update we also took a decision to exclude magnetic or electrical stimulation interventions (e.g. transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), transcranial magnetic stimulation or epidural cortical stimulation) as we considered these to be an adjunct to SLT rather than an SLT approach. The effectiveness of tDCS interventions for aphasia will soon be addressed within a separate review (Elsner 2012).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome chosen to indicate the effectiveness of an intervention that aims to improve communicative ability must reflect the ability to communicate in real world settings, that is functional communication. Providing a definition for the concept of functional communication is problematic and makes evaluation difficult. The ability to functionally communicate relates to language or communicational skills sufficient to permit the transmission of a message via spoken, written or non‐verbal modalities, or a combination of these channels. Success is typically and naturalistically demonstrated through successful communication of the message ‐ the speaker communicates their message and the listener understands the message communicated. Attempts to measure this communication success formally vary from analysis of discourse interaction in real life to sampling of specific discourse tasks. Other more formal tools might include the Communicative Abilities of Daily Living (CADL) (Holland 1980) or the Communicative Effectiveness Index (CETI) (Lomas 1989).

Secondary outcomes

Given the lack of a comprehensive, reliable, valid and globally accepted functional communication evaluation tool, surrogate outcome measures of communication ability include formal measures of receptive language (oral, written and gestural), expressive language (oral, written and gestural) or overall level of severity of aphasia where receptive and expressive language are measured using language batteries. Such tools might include, for example, the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) (Kertesz 1982) or the Porch Index of Communicative Abilities (PICA) (Porch 1967). Other secondary outcomes of relevance to this review include psychosocial impact (i.e. impact on psychological or social well‐being including depression, anxiety and distress), patient satisfaction with intervention, number of dropouts (i.e. the number of participants dropping out at treatment or follow‐up phases for any reason), compliance with allocated intervention (i.e. the number of participants voluntarily withdrawing from their allocated intervention), economic outcomes (such as costs to the patient, carers, families, health service and society), and carer and family satisfaction. Measures of overall functional status (e.g. Barthel) were extracted in the original review as one of a number of primary outcomes. We also extracted these data, where available, as an indicator of overall severity of stroke but this information is now presented as a patient descriptor within the Characteristics of included studies table. A full list of outcome measures included in the review and their references can be found in Appendix 1.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We did not impose any language restrictions.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register, which was last searched by the Managing Editor on 6th June 2011. In addition, we searched MEDLINE (1966 to July 2011) (Appendix 2) and CINAHL (1982 to July 2011) (Appendix 3) using comprehensive search strategies. For the original version of the review searches of MEDLINE (1966 to 1998) and CINAHL (1982 to 1998) were carried out using simple combinations of text words describing aphasia and SLT. We also searched major trials registers for ongoing trials including ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/), the Stroke Trials Registry (www.strokecenter.org/trials/) and Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com).

Searching other resources

-

We handsearched the International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders (formerly the International Journal of Disorders of Communication, the European Journal of Disorders of Communication and the British Journal of Disorders of Communication) from 1969 to December 2005. Since 2006 this journal has been indexed in MEDLINE so our comprehensive electronic search identified any relevant trials published in the journal after that date.

-

We checked reference lists of all relevant articles to identify other potentially relevant randomised studies.

-

We contacted all British universities and colleges where SLTs are trained and all relevant 'Special Interest Groups' in the UK to enquire about any relevant published, unpublished or ongoing studies.

-

We approached colleagues and authors of relevant randomised trials to identify additional studies of relevance to this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Our selection criteria for inclusion in this review were:

-

the study participants included people with aphasia as a result of stroke;

-

the SLT intervention was designed to have an impact on communication; and

-

the methodological design was a randomised controlled trial.

One review author (MB) screened titles and abstracts of the records identified through the electronic searches described above and excluded obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained hard copies of all the remaining studies that fulfilled the listed inclusion criteria. Two review authors (MB and HK or PE) independently assessed the studies based on the inclusion criteria and decided whether to include or exclude studies. We resolved any disagreements through discussion. Studies judged ineligible for inclusion, together with reasons for their exclusion, are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

The data extraction form used in the original review was unavailable so we created and piloted another for use in this review update. Two review authors (MB and HK) independently confirmed the data for the trials as included in the original review and extracted the data for the additional trials included in the updates. We resolved any disagreements through discussion. We extracted the following data: number of sites, methods of randomisation, blinding, attrition from intervention, co‐interventions, confounder details, number of participants, age, education, handedness, gender, native language, severity of aphasia, time post‐onset, frequency and duration of therapy, details of intervention, outcome measures used and time points, evidence of an a priori sample size calculation, intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis and summary data. We attempted to contact investigators for any missing data (or data in a suitable format) for inclusion in the review.

Where we identified a cross‐over trial, we based decisions relating to the suitability of the data (either up to or beyond the cross‐over phase) on careful consideration in relation to a range of factors including the intervention(s) used, the timing of the intervention(s), the impact of any treatment carry over and whether data from relevant paired comparisons within the trial were available. Whenever possible, in such cases we sought individual patient data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the trials for methodological quality, paying attention to whether there was protection from the following types of bias: selection bias (i.e. true random sequencing and true concealment up to the time of allocation), performance bias (i.e. differences in other types of treatment (co‐interventions) between the groups, attrition bias (i.e. withdrawal after trial entry) and detection bias (i.e. 'unmasked' assessment of outcome). We coded concealed allocation as 'low risk', 'unclear' or 'high risk' according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). In addition, we extracted information on whether power calculations and ITT analyses were employed. In some cases, for example where all participants were accounted for in the final results, this was not applicable.

Measures of treatment effect

We conducted the review using RevMan 5.1 (RevMan 2011) for statistical analysis. We have recorded descriptive information for each trial (characteristics of participants, interventions and outcomes) in the Characteristics of included studies table and issues relating to the methodological quality of the trial in the 'Risk of bias' tables. Where trials made a similar comparison and were judged sufficiently similar in respect of their descriptive information, we pooled the summary data (where available) using meta‐analysis. We expressed continuous data as differences in means or standardised difference in means and dichotomised data as odds ratios (OR). We used 95% confidence intervals (CI) throughout the review.

The results of the trials in this review reported measures based on differences in final value scores (scores taken at the end of the intervention) and change‐from‐baseline scores (also known as change scores). Although the mean differences (MD) based on change‐from‐baseline scores in randomised trials can generally be assumed to address the same intervention effects as MD analysis based on final value scores, change‐from‐baseline scores are given higher weights in analysis than final value scores (Higgins 2011). For this reason, we have used final value scores within the meta‐analyses wherever possible. We do not report change‐from‐baseline scores unless they were the only available values used to report trial results (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic where any heterogeneity observed may be considered moderate (an I2 value of 30% to 60%), substantial (50% to 90%) or considerable (75% to 100%) (Higgins 2011). Where we observed important heterogeneity (based of the I2 value together with significant evidence of heterogeneity as per the Chi2 test P value) we used a random‐effects model (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Where a single outcome measure was assessed and reported across trials using different measurement tools, we presented these data in a meta‐analysis using a SMD summary statistic. In cases where the direction of measurement differed it was necessary to adjust the direction of some measures to ensure that all the scales operated in the same direction. For example, measures of comprehension ability generally increase with increasing ability, but in some cases (e.g. the Token Test) improving comprehension skills might be reflected by decreasing scores and so it was necessary to multiply the mean values by ‐1 to ensure that all the scales operated in the same direction. Standard deviation (SD) values were unaffected and we have presented these within the meta‐analysis without the need for a directional change.

In cases where only partial summary data were reported, for example mean final value scores were available but SDs were unavailable (Wertz 1981), we attempted to calculate these values from available information. When this was not possible we imputed the SD to facilitate inclusion of the trial within the review by using a SD value from a similar participant group (Higgins 2011). We have reported details of where the imputed SD values have come from within the text. Where there was a choice of possible SD values, we took the approach of imputing the highest and lowest values to ensure that both methods provided a similar overall conclusion and then used the highest value in the presentation of the trial within the forest plot.

Where results in a particular comparison were only available in a mixture of final value and change‐from‐baseline scores, we presented these data graphically using SMDs but we were unable to pool these results in a meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not plan any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

The original review did not include any planned sensitivity analyses. However, in this updated review we aimed to reflect developments in clinical practice including trials where SLT interventions were delivered or facilitated by non‐speech and language therapists. We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to evaluate any impact the inclusion of these groups of trials may have had on the results of the review and the impact of trial quality.

Results

Description of studies

The original 1999 review included 12 trials. We revisited the decision taken in the original review to include Kinsey 1986 and Hartman 1987. We have excluded quasi‐randomised trials such as Hartman 1987 from this review update, while Kinsey 1986 reports a comparison of methods of providing therapy materials rather than a comparison of therapy interventions. Thus of the original 12 trials included in the 1999 review, 10 trials remained in the 2010 review update. We identified an additional 20 trials in the update search and we revised the decision to exclude one other trial (Shewan 1984) from the original review following communication with the trialists who confirmed that it was a RCTl. This review is based on data from a total of 39 included trials.

Results of the search

Our search strategy identified 1961 records within CINAHL database (1982 to July 2011) and 4450 records within the MEDLINE database (1966 to July 2011). Following our 2011 search we identified 15 ongoing studies (CACTUS; Crosson 2007; FUATAC; Godecke 2011; IHCOP; IMITATE; Kukkonen 2007; Maher 2008; MIT Netherlands 1; MIT Netherlands 2; MIT USA; RATS‐3; Raymer; SP‐I‐RiT; Varley 2005); these are likely to be eligible for inclusion in the review at a later date. These studies are detailed in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table. In total we identified nine new trials for inclusion in this review update.

Included studies

We have included a total of 39 trials (which randomised 2518 participants) in this review. Of these, 30 were included in the 2010 review, four trials listed as ongoing in 2010 have since reported and there are five newly identified trials. Six trials randomised individuals across three or more groups (trial arms) but for the purposes of this review and the meta‐analyses we have presented and pooled the data within paired comparisons indicated as i, ii or iii. For example, data from Yao 2005 are presented across three 'trials' of (1) group SLT versus no SLT (Yao 2005i), (2) individual SLT versus no SLT (Yao 2005ii) and (3) group SLT versus individual SLT (Yao 2005iii). Other trials affected were Katz 1997i, Katz 1997ii, Lincoln 1982i, Lincoln 1982ii, Lincoln 1982iii, Shewan 1984i, Shewan 1984ii, Shewan 1984iii, Smith 1981i, Smith 1981ii, Smith 1981iii, Wertz 1986i, Wertz 1986ii, Wertz 1986iii,Zhang 2007i, and Zhang 2007ii. Further details can be found in the Characteristics of included studies. In these trials there was a risk of including the same group of participants (usually the control group) twice in a single meta‐analysis and so we split the number of participants in the control group across the two 'trials' that shared that comparison group (Higgins 2011). In the case of continuous data the mean and SD values remained the same. In the case of dichotomous data both the number of events and total number of patients were split across the relevant number of arms. In keeping with previous reviews where this method has been used and for ease of reading, these paired randomised comparisons will be referred to as trials from this point onwards.

Nine trials employed a cross‐over design (Crerar 1996; Elman 1999; Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1982ii; Lincoln 1982iii; Lincoln 1984b; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wertz 1986iii). We carefully considered the suitability of each cross‐over trial for inclusion within the review. We considered factors including the suitability of the design, the intervention(s) used, the timing of the intervention(s), the impact of any treatment carry over and finally whether data from relevant paired comparisons from the cross‐over data were available. For six trials we only extracted data up to the point of cross‐over (Crerar 1996; Elman 1999; Lincoln 1982iii; Lincoln 1984b; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii). In some cases though, the treatment that participants were allocated to receive following cross‐over was 'no SLT'. In these cases, the 'no SLT' input after cross‐over could be used as a follow‐up period.

In contrast, Lincoln 1982 was also a cross‐over trial in design with participants randomly allocated to one of four groups with a sequence of interventions that included one active treatment or placebo either preceded by or followed by conventional SLT. We were able to access the unpublished individual patient data for this review. This access to the data, the design, nature and manner of SLT delivery within the trial and the clinical relevance of the comparisons made it possible to include two paired comparisons of those groups within the review:

-

SLT + operant training versus SLT + social support (Lincoln 1982i);

-

operant training + SLT versus social support + SLT (Lincoln 1982ii).

In addition, by taking the individual data at the point of measurement prior to the cross‐over it was also possible to extract and compare the data from those that had received conventional SLT and compare it to those participants that received a social support and stimulation intervention (Lincoln 1982iii).

We have presented data from 51 randomised comparisons as they relate to the effectiveness of SLT for aphasia following stroke, which compare: (1) SLT versus no SLT, (2) SLT versus social support and stimulation and (3) SLT A versus SLT B. We have presented details of data within each comparison below with further details on each trial available in the Characteristics of included studies table. Further participant details can be found in Table 1, an overview of the SLT interventions can be found in Appendix 4, while details of the assessment tools used can be found in Appendix 1. A summary of all the findings of the results is available at the end of the results section.

| Study ID | Number | Male/female | Age in years mean (standard deviation) | Post‐onset mean (standard deviation) (range) | Aphasia severity mean (standard deviation) |

| 153 | SLT: 40/36 Social support: 42/35 | SLT: 71 (range 32 to 97) Social support: 70 (range 40 to 92) | Admission to randomisation median 12 (interquartile range 9 to 16) days | TOMs SLT: 1.9 (1.2) (severe n = 47) Social support: 1.9 (1.1) (severe n = 51) | |

| 97 | Intensive: 26/25 | Intensive: 71.2 (14.9) (range 26 to 92) | Intensive: 34.2 (19.1) days | WABAQ | |

| 8 | Verb SLT: 2/1 Preposition SLT: 5/0 | Verb SLT: 50.3 (8.5) (range 44 to 60) Preposition SLT: 48.8 (13.77) (range 27 to 64) | Verb SLT: 87.33 (40.61) (range 60 to 134) months Preposition SLT: 66.4 (20.96) (range 39 to 86) | WABAQ Verb SLT: 76.2 (9.81) Preposition SLT: 69.3 (16.58) | |

| 133 (of 155 randomised) | Conventional: 35/30 | Conventional: 70 (8.7) | Conventional: median 4 (range 4 to 266) weeks | Baseline FCP scores for n = 98 retained until post‐therapy test Conventional: 42.4 (20.8) | |

| 17 | Intensive: 5/3 | Intensive: 58.1 (11.8) | Intensive: 3.2 (1.8) months | AAT | |

| 14 | Programmed instruction: 7/0 | Programmed instruction: 57.6 (9.2) (range 44 to 69) | Programmed instruction: 24.7 (23.6) (range 0 to 66) months | Programmed instruction: severe | |

| 18 (of 19 randomised) | Computer‐mediated: 4/4 | Computer‐mediated: 62 (9.0) | Computer‐mediated: 13 (range 11 to 16) months | Computer‐mediated: ANELT‐ A 34 (9); BNT 63 (37) | |

| 8 | Not reported | Gesture cue: 52.9 (6.0) | Gesture cue: 15.3 (4.1) (range 10 to 20) months | Not reported | |

| 24 | Conventional: 7/5 | Conventional: 58.3 (11.4) (range 38 to 79) | Conventional: 32.5 (28.7) (range 7 to 103) months | Conventional: SPICA 7 mild to moderate, 7 moderate to severe | |

| 12 | Functional SLT: 5/1 | Functional: 51.6 (15) | Functional: 26.8 (20.1) (range 6 to 58) months | BDAE Severity Rating | |

| 60 | Group SLT: unclear | Group SLT: unclear | Not reported | Not reported | |

| 54 | Group SLT: unclear | Group SLT: unclear | Not reported | Not reported | |

| 54 | Group SLT: unclear | Group SLT: unclear | Not reported | Not reported | |

| 42 (reported data on 36) | Computer‐mediated: unclear | Computer‐mediated: 61.6 (10) | Computer‐mediated: 6.2 (5.2) years | PICA overall percentile; WABAQ Computer‐mediated: 57.3 (17.9); 68.9 (24.3). | |

| 40 (of 42 randomised) | Computer‐mediated: unclear | Computer‐mediated: 61.6 (10) | Computer‐mediated: 6.2 (5.2) years | PICA overall percentile; WABAQ Computer‐mediated: 57.3 (17.9); 68.9 (24.3) | |

| 123 | SLT: 33/29 No SLT: 23/38 | SLT: 76 (range 38 to 94) No SLT: 79 (range 39 to 94) | SLT: 3 (25th‐75th; 2 to 4) days No SLT: 3 (25th‐75th; 2 to 4) days | ANELT‐A median (25th to 75th) SLT: 1 (0 to 1.4) No SLT: 1 (0 to 1.4) | |

| 94 | Conventional: 38/21 Volunteer‐facilitated: 22/13 | Conventional: 56 (17) | Within first month after stroke | Conventional: moderate‐severe | |

| 12 | SLT/operant train: 3/3 | SLT/operant train: 54.33 (6.68) (range 45 to 63) SLT/social support: 51.33 (7.97) (range 39 to 63) | SLT/operant train: 3.17 (1.60) (range 1 to 5) months | SLT/operant train: moderate | |

| 12 | Operant train/SLT: 5/1 | Operant train/SLT: 57.67 (5.72) (range 51 to 64) | Operant train/SLT: 2.33 (1.55) (range 1 to 5) months | Operant train/SLT: moderate | |

| 18 | Conventional SLT: 7/5 | Conventional SLT:52.83 (7.18) (range 39 to 63) | Conventional SLT: 4.17 (2.76) (range 1 to 10) months | Conventional SLT: moderate | |

| (data for 58% of randomised participants) | 191 | Conventional: unclear | Conventional: unclear | Conventional: 10 weeks | Not reported |

| 12 | Operant train: 4/2 Placebo: 5/1 | Operant train: 52.33 (11.50) (range 32 to 64) | Operant train: 5.5 (4.89) (range 1 to 12) months | Operant train: severe | |

| 36 | SLT: 9/10 No SLT: 10/7 | SLT: 7 = 40 to 65 years; 12 = 65 to 80 years No SLT: 8 = 40 to 65 years; 9 = 65 to 80 years | SLT: 8 = 7 to 20 days; 11 = 20 to 45 days No SLT: 7 = 7 to 20 days; 10 = 20 to 45 days | BDAE SLT: 60.48 (11.83) No SLT: 58.22 (5.06) | |

| 30 | Functional: unclear | Functional: unclear | Functional: unclear | Functional: unclear | |

| 95 | MacKay 1988: 46/49 | MacKay 1988: median 75 | MacKay 1988: mean 30 months | Not reported | |

| 31 | Volunteer‐facilitated: 12/3 | Volunteer‐facilitated: 67.2 (8.6) | Volunteer‐facilitated: 30.9 (29.5) (range 4 to 115) weeks | PICA percentile volunteer‐facilitated: 53.9 (23.5) | |

| 20 | Constraint‐induced: 7/3 Volunteer‐facilitated: 9/1 | Constraint‐induced: 50.2 (10.13) | Constraint‐induced: 30.7 (18.9) (range 6 to 72) months | AAT profile score | |

| 13 | Intensive SLT: 6 | Intensive SLT: 61.4 (9.72) (range 48.44 to 74.5) | Intensive SLT: 36.2 (28.2) (range 8.6 to 69.8) months | WABAQ Intensive SLT: 51.1 (17.8) (range 28.0 to 69.4) | |

| 25 | Computer: 8/3 Therapist: 8/6 | Computer: 56.6 (9.2) (range 41.7 to 68) Therapist: 61.1 (14.8) (range 35.2 to 81.7) | Computer: 66.7 (71.5) (range 13.8 to 253.2) months Therapist: 41.3 (45.7) (range 12.2 to 166) months | WABAQ Computer: 62.0 (19.9) Therapist: 47.3 (27.9) | |

| 21 | STACDAP: 5/5 | STACDAP: 70.3 (range 58 to 83) | STACDAP: 15.2 (range 3 to 35) months | STACDAP: FE‐scale 2.6 (0 to 6), oral comp (BDAE and Token Test) 26.4 (0 to 46) | |

| 17 | Constraint‐induced: 6/4 | Constraint‐induced: 55.4 (10.9) | Constraint‐induced: 98.2 (74.2) months | Constraint‐induced: 2 mild, 5 moderate, 3 severe | |

| 58 | Semantic: 18/11 | Semantic: 66 (10) | Semantic: mean 4 (range 3 to 5) months | ANELT‐A score | |

| 80 | Cognitive linguistic: 14/24 Communicative: 24/18 | Cognitive linguistic: 68 (13) Communicative: 67 (15) | Cognitive linguistic: 22 (range 11 to 37) days Communicative: 23 (9 to 49) days | ANELT‐A score Cognitive linguistic: 21.4 (11.0) Communicative: 21.0 (11.1) | |

| 5 | Sentence mapping: 0/3 | Sentence mapping: range 31 to 74 | Sentence mapping: range 2 to 9 years | Sentence mapping: BDAE 1 to 2, phrase length 2.5 to 4 | |

| 52 | Language‐orientated: 18/10 | Language‐orientated: 62.18 (range 29 to 82) | Language‐orientated: range 2 to 4 weeks | Language‐orientated: 9 mild, 6 moderate, 13 severe | |

| 53 | Language‐orientated: 18/10 | Language‐orientated: 62.18 (range 29 to 82) | Language‐orientated: range 2 to 4 weeks | Language‐orientated: 9 mild, 6 moderate, 13 severe | |

| 49 | Conventional: 14/10 | Conventional: 65.63 (range 48 to 85) | Conventional: range 2 to 4 weeks | Conventional: 8 mild, 3 moderate, 13 severe | |

| 33 (of 41 randomised) | Conventional: 11/4 | Conventional: 65.73 (8.78) (range 48 to 77) | Conventional: 17.4 (24.07) (range 2 to 36) months | Aphasia severity: unclear | |

| 33 | Intensive: 12/4 | Intensive: 62 | Not reported | MTDDA (mean error score percentage) | |

| 31 | Conventional: 10/4 | Conventional: 63 | Not reported | MTDDA (mean error score percentage) | |

| 30 | Intensive: 12/4 | Intensive: 62 | Not reported | MTDDA (mean error score percentage) | |

| 10 | Task‐specific: 0/5 | Task‐specific: 61.8 (17.05) (range 40 to 77) | Task‐specific: 21 (22.4) (range 5 to 60) months | FE‐scale and M‐S Comprehension Test | |

| 59 | Intensive SLT: 14/18 Conventional SLT: 15/12 | Intensive SLT: 70.3 (12.8) Conventional SLT: 67.7 (15.4) | Intensive SLT:3.2 (2.2) days Conventional SLT: 3.4 (2.2) days | WABAQ median (IQR) Intensive SLT: 31.0 (47) Conventional SLT: 9.0 (34.1) | |

| 67 | Not reported | (15 weeks after stroke) | Group SLT: 4 weeks | (15 weeks after stroke) | |

| 78 | Conventional: unclear | Conventional: 59.2 (6.7) | Conventional: 6.6 (4.8) weeks | PICA overall percentile Conventional: 46.59 (16.05) | |

| 83 | Volunteer‐facilitated: 37/6 | Volunteer‐facilitated: 60.2 (6.7) | Volunteer‐facilitated: 7.1 (5.8) weeks | PICA overall percentile | |

| 81 | Volunteer‐facilitated: 37/6 | Volunteer‐facilitated:60.2 (6.7) | Volunteer‐facilitated: 7.1 (5.8) weeks | PICA overall percentile | |

| 236 | Conventional: unclear | Conventional: (range 39 to 81) | Not reported | Not reported | |

| 36 | SLT: 10/9 No SLT: 11/6 | SLT: 63.40 (7.82) No SLT: 59.36 (7.69) | SLT: 29.45 (10.63) days No SLT: 27.80 (9.79) days | ABC AQ SLT: 48.70 (33.49) No SLT: 49.87 (26.83) | |

| 37 | SLT: 11/9 No SLT: 11/6 | SLT: 60.80 (8.13) No SLT: 59.36 (7.69) | SLT: 28.10 (9.15) days No SLT: 27.80 (9.79) days | ABC AQ SLT: 48.43 (29.18) No SLT: 49.87 (26.83) | |

| 138 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

AAT: Aachen Aphasia Test

ABC: Aphasia Battery of Chinese

ANELT: Amsterdam‐Nijmegen Everyday Language Test

AQ: Aphasia Quotient

BDAE: Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination

BNT: Boston Naming Test

FCP: Functional Communication Profile

FE‐scale: Functional‐Expression scale

IQR: interquartile range

MTDDA: Minnesota Test for the Differential Diagnosis of Aphasia

M‐S Comprehension Test: Morpho‐Syntactic Comprehension Test

PICA: Porch Index of Communicative Abilities

SLT: Speech and Language therapy/therapist

SPICA: Shortened Porch Index of Communicative Abilities

STACDAP: Systematic Therapy for Auditory Comprehension Disorders in Aphasic Patients

TOMs: Therapy Outcome Measures

WAB: Western Aphasia Battery

WABAQ: Western Aphasia Battery Aphasia Quotient

1. SLT versus no SLT

We included 19 randomised comparisons in this section (Doesborgh 2004; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Laska 2011; Lincoln 1984a; Liu 2006; Lyon 1997; MacKay 1988; Smania 2006; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wu 2004; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii; Zhao 2000) involving 1414 randomised participants. The SLT intervention was typically delivered by a speech and language therapist. In two trials therapy was facilitated by a therapist‐trained volunteer (MacKay 1988; Wertz 1986ii). In trials conducted in China the therapy intervention was delivered by a doctor or nurse in four trials (Wu 2004; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Zhao 2000), other therapists in the rehabilitation setting (Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii) and it was unclear who facilitated the SLT intervention in one further comparison (Liu 2006). Two additional trials (Prins 1989; Shewan 1984) compared groups that did and did not receive SLT but the participants were not randomly assigned to these 'no SLT' groups and they were thus excluded from this review.

The trials in this section employed a range of SLT interventions, namely conventional SLT (Lincoln 1984a; Liu 2006; Smania 2006; Smith 1981ii; Wertz 1986i; Wu 2004; Yao 2005ii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii), intensive SLT (Laska 2011; Smith 1981i), group SLT (Yao 2005i), volunteer‐facilitated (MacKay 1988; Wertz 1986ii), computer‐mediated SLT (Doesborgh 2004; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii) and functionally‐based SLT involving a communicative partner (Lyon 1997). Laska 2011 also further described their SLT intervention as early language enrichment therapy, delivered two to four days after stroke. An acupuncture co‐intervention was delivered alongside the SLT intervention in two comparisons (Liu 2006; Zhang 2007ii).

Most participants randomised to the 'no SLT' groups received no alternative treatment or support (Doesborgh 2004; Katz 1997i; Laska 2011; Lincoln 1984a; Liu 2006; Lyon 1997; MacKay 1988; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wu 2004; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii). Only seven trials described an intervention within these 'no SLT' groups. In six cases we considered the control interventions to be similar to standard post‐stroke care in the local region ‐ participants were visited at home by a health visitor (Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii), received limb apraxia therapy (Smania 2006) or medication (Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii; Zhao 2000). In addition, one control group received computer‐based cognitive tasks ('arcade‐style games') (Katz 1997ii) that had been specifically designed not to target language rehabilitation. In all seven cases we included these groups as 'no SLT' control groups in the review.

SLT interventions were delivered across a wide range of times after the onset of aphasia with timings difficult to summarise because of a lack of detailed reporting. Some trialists recruited participants in the early stages after the onset of stroke ‐ within four days (Laska 2011), up to 45 days (Liu 2006), 10 weeks (Lincoln 1984a), three months (Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii) or six months (Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii) after the stroke. Other trials recruited participants longer after stroke, for example between two months and three years after stroke (Smania 2006). Other participants were recruited one year or more after their stroke ‐ up to 17 months (Doesborgh 2004); two years (MacKay 1988) (61% of participants); 10 years (range 13 to 124 months) (Lyon 1997); 19 years (Katz 1997i) or up to 22 years (Katz 1997ii) after the onset of aphasia. Six trials failed to report the timing of the SLT intervention in relation to the onset of participants' aphasia (Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Wu 2004; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Zhao 2000).

The frequency of SLT was reported as number of times daily or hours per day or per week. SLT was provided daily (duration unclear) within two trials (Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii). SLT was provided weekly for up to two hours (Doesborgh 2004; Lincoln 1984a; Smith 1981ii), three hours (Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Smania 2006), four hours (Laska 2011; Smith 1981i), six hours (MacKay 1988), eight hours (Lyon 1997) or 10 hours (Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii). An additional five comparisons did not report the frequency of the SLT intervention (Liu 2006; Wu 2004; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii; Zhao 2000). Where specified, the duration of the SLT intervention varied from three weeks (Laska 2011); two months (Zhao 2000); up to three months (Doesborgh 2004; Smania 2006; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii); between five and six months (Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Lincoln 1984a; Lyon 1997; Wu 2004) or for up to one year (MacKay 1988; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii).

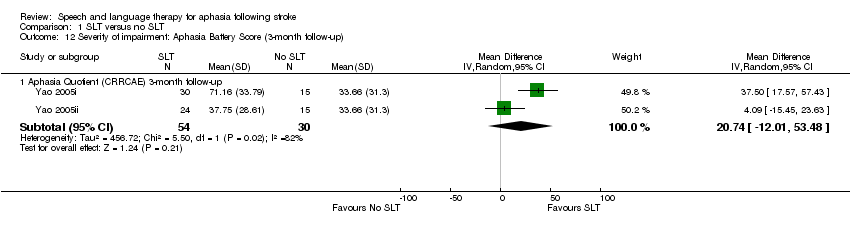

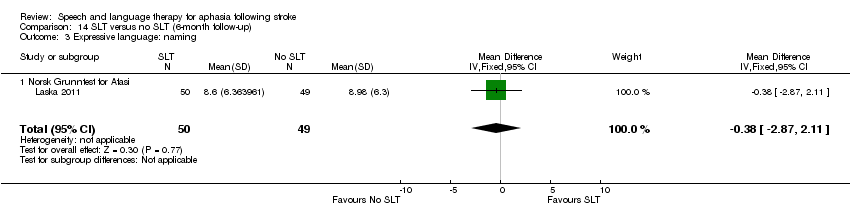

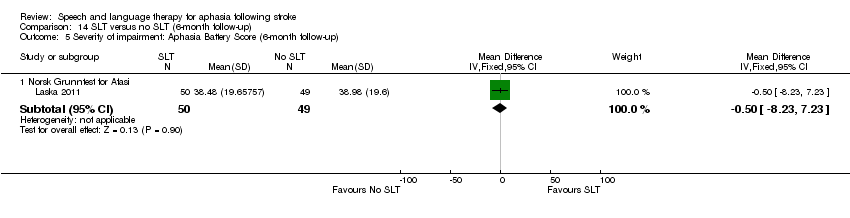

The 19 randomised comparisons in this section used a wide range of outcome measures including functional communication, receptive language, expressive language, severity of impairment, psychosocial impact and economic outcomes. One of the 14 trials did not report any outcome measures (Wu 2004). Seven trials carried out follow‐up assessments at two months (Smania 2006), three months (Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii), six months (Laska 2011; MacKay 1988) and 12 months (MacKay 1988) after SLT.

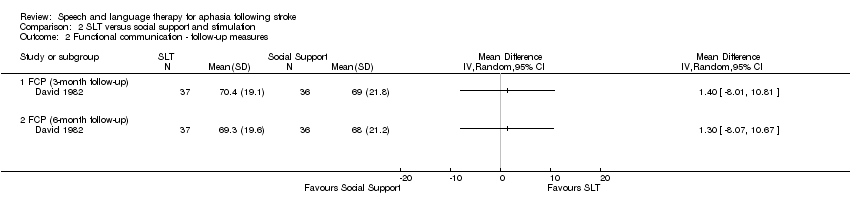

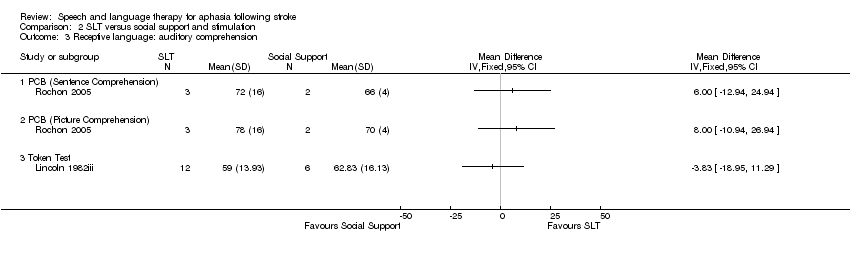

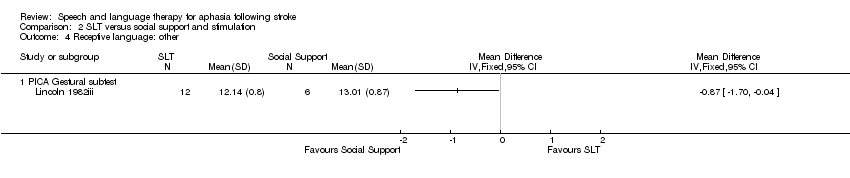

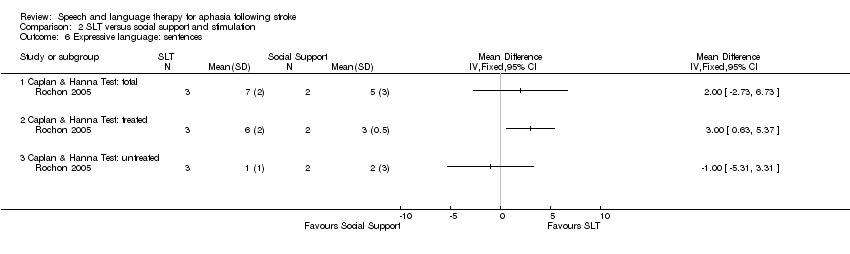

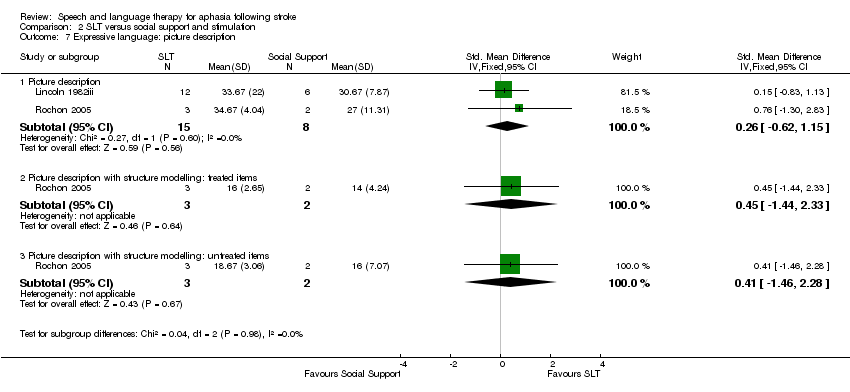

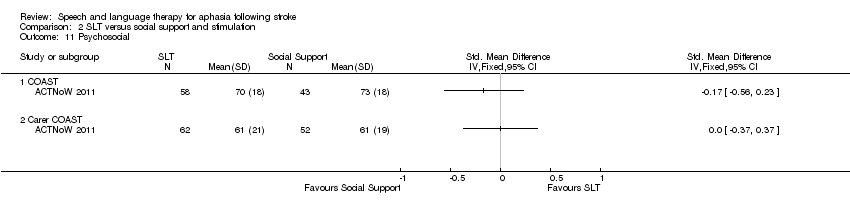

2. SLT versus social support and stimulation

We included seven trials in this section (ACTNoW 2011; David 1982; Elman 1999; Lincoln 1982iii; Rochon 2005; Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii) with 432 randomised participants. A range of SLT approaches were reported including conventional SLT (ACTNoW 2011; David 1982; Lincoln 1982iii; Shewan 1984iii), group SLT (Elman 1999), language‐oriented SLT (Shewan 1984ii) and sentence mapping SLT (Rochon 2005). The social support and stimulation interventions were provided by volunteers not known to the participants with aphasia (ACTNoW 2011; David 1982), nursing staff (Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii), speech and language therapists (Lincoln 1982iii), a trained research assistant (Rochon 2005) or through other social group activities including movement classes, creative arts groups, church activities or support groups (Elman 1999). All visitors providing the ACTNoW 2011 social support received training and a manual of non‐therapeutic activities, suitable conversation topics and access to equipment. David 1982 provided their volunteers with detailed information on their patient's communication problems and they were instructed to "encourage their patient to communicate as well as possible". Similarly, the nursing staff volunteers (Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii) were given some information about aphasia and instructed to "stimulate communication to the best of their ability". In all four trials the volunteers were given no guidance or instruction in SLT techniques.

The duration of participants' aphasia varied between trials and was reported as: an average of 12 days (ACTNoW 2011), up to four weeks (Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii), up to three years (David 1982; Lincoln 1982iii), seven months to 28 years (Elman 1999) or between two and nine years (Rochon 2005). Interventions were provided weekly for up to two (David 1982; Lincoln 1982iii), 2.5 (ACTNoW 2011), three (ACTNoW 2011; Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii) or five hours (Elman 1999) over the course one (Lincoln 1982iii), four (ACTNoW 2011; Elman 1999), five (David 1982) or 12 months (Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii).

Outcome measures used in this comparison included measures of functional communication, receptive language, expressive language and levels of severity of impairment. Two trials carried out follow‐up measures at four weeks (Rochon 2005), three months and six months (David 1982) after the treatment period.

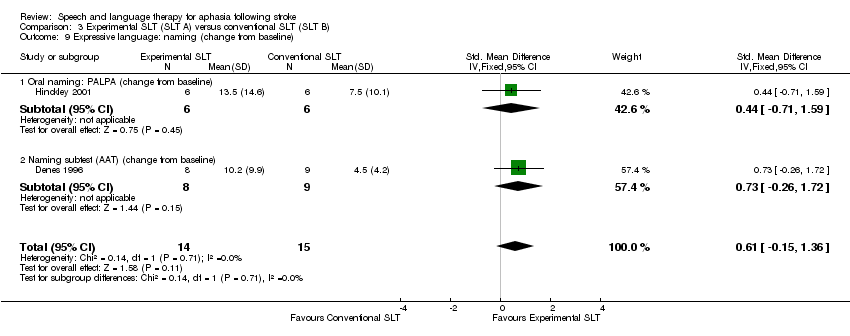

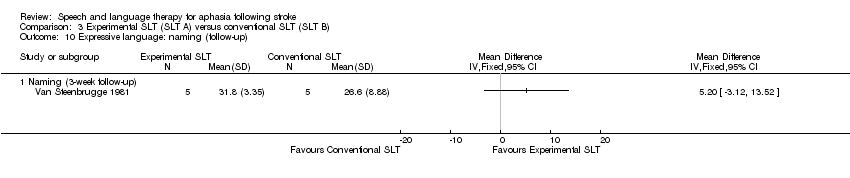

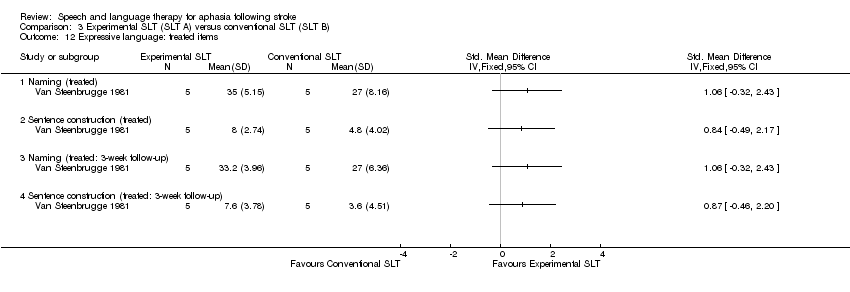

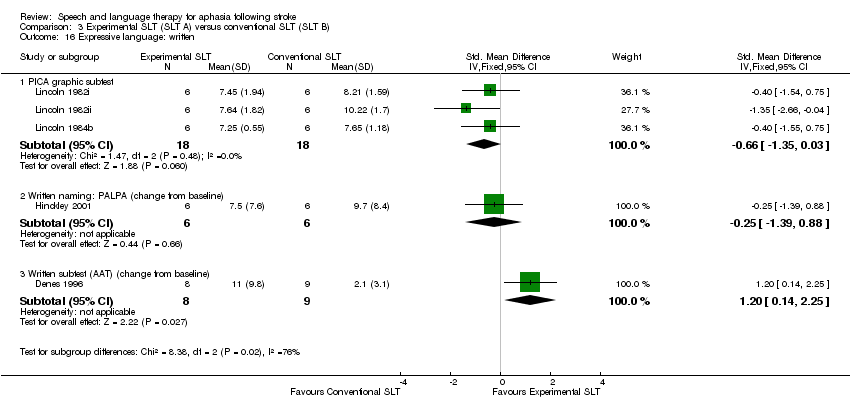

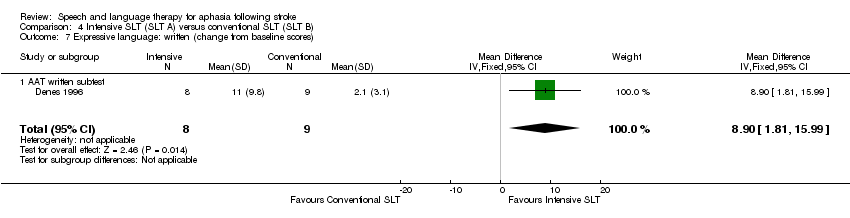

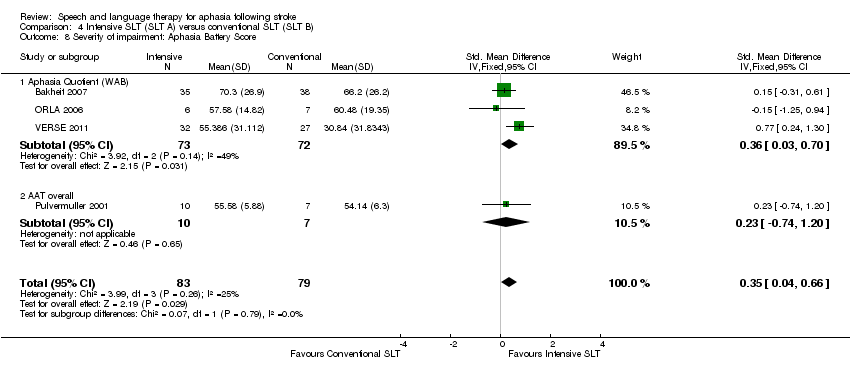

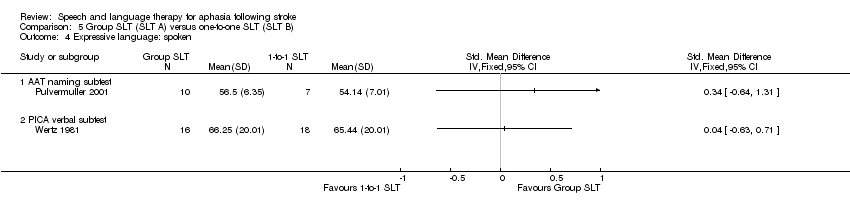

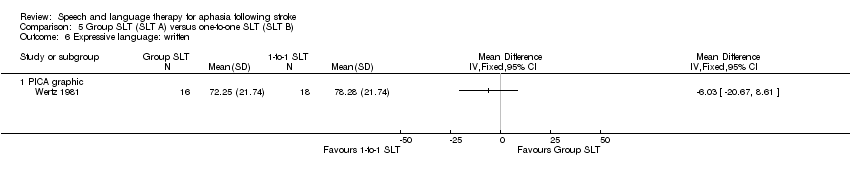

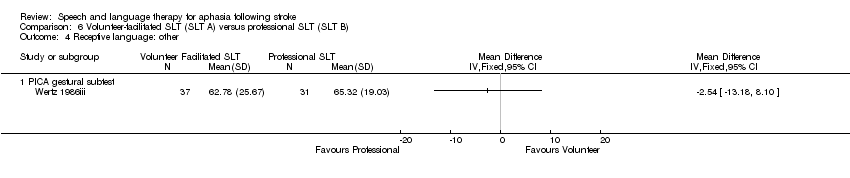

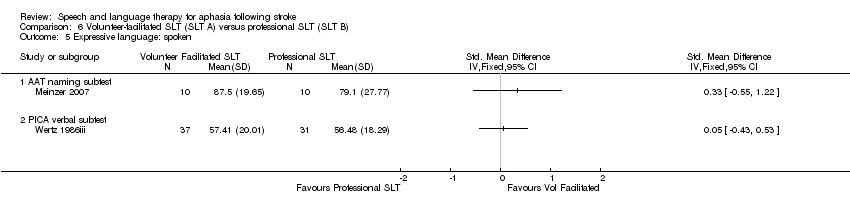

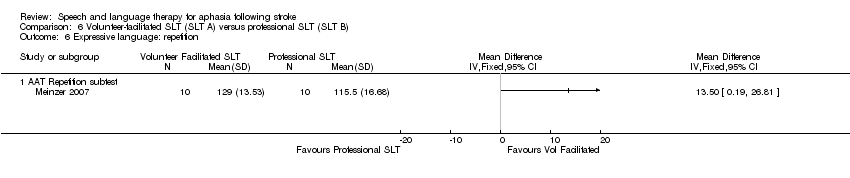

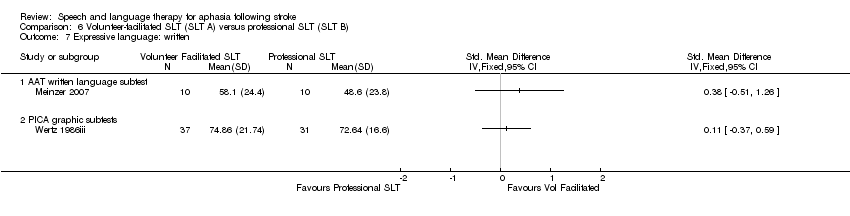

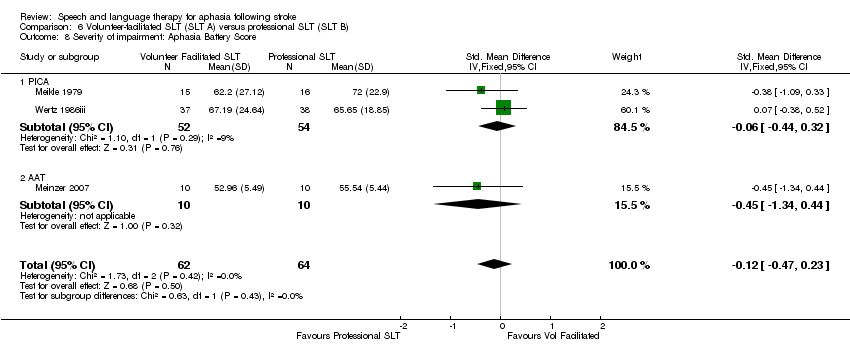

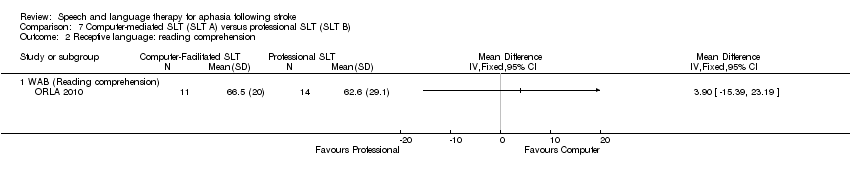

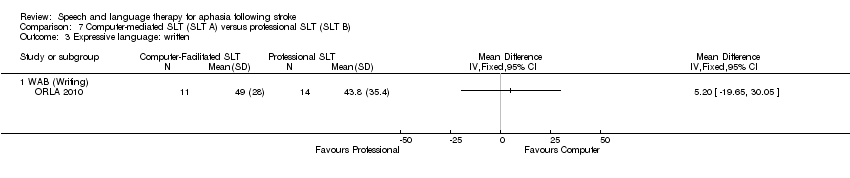

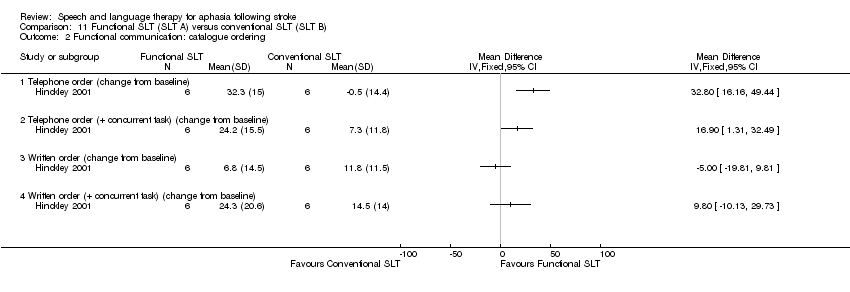

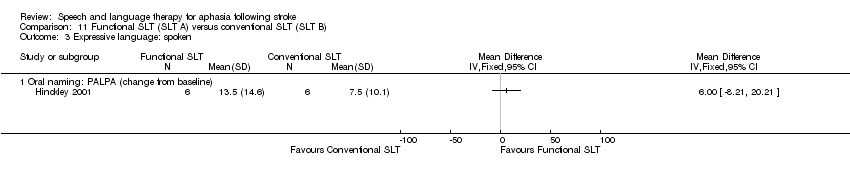

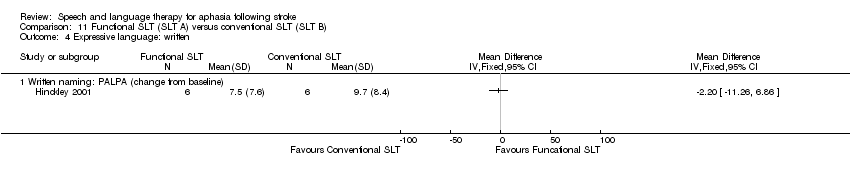

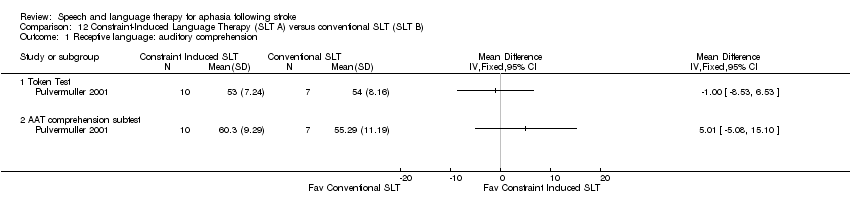

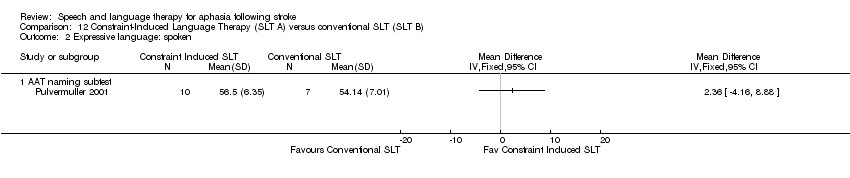

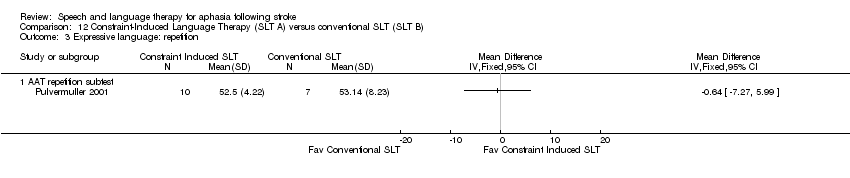

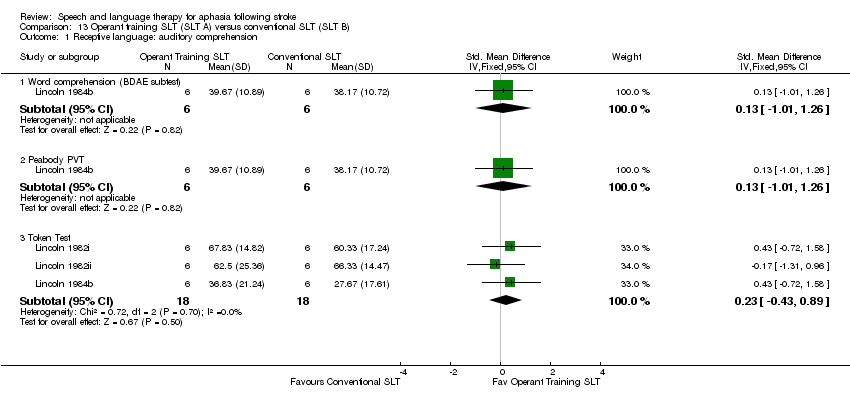

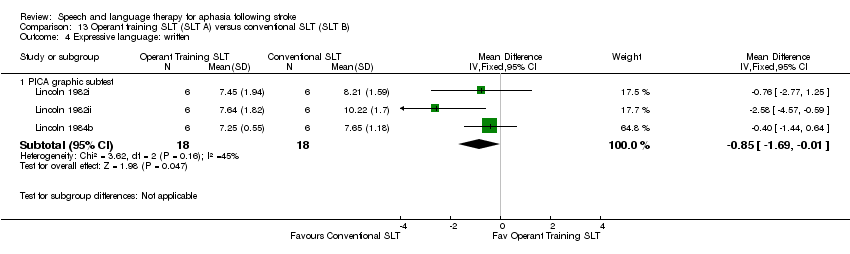

3. SLT A versus SLT B

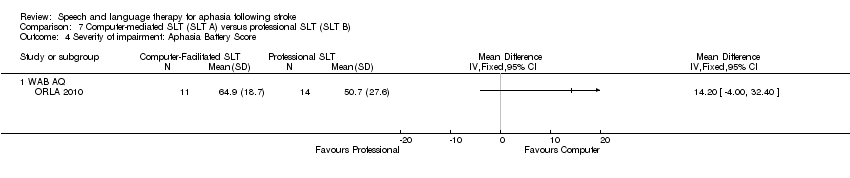

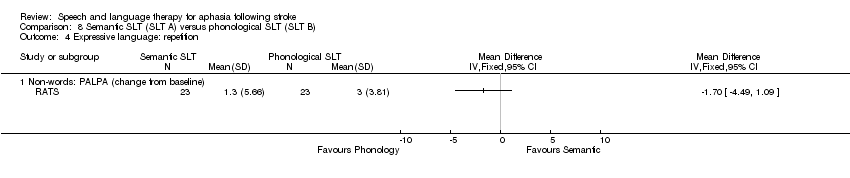

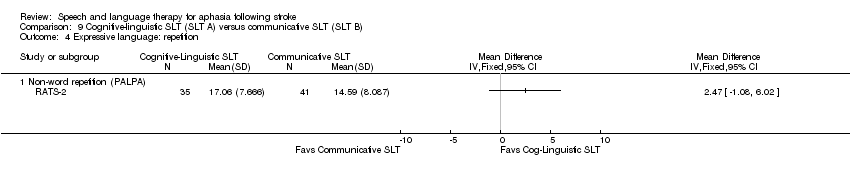

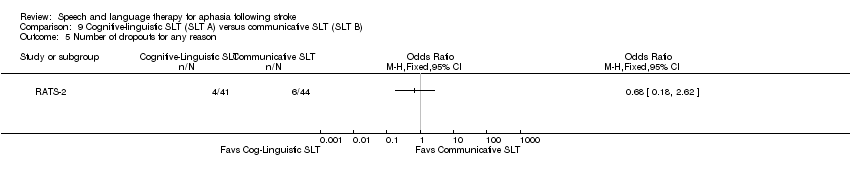

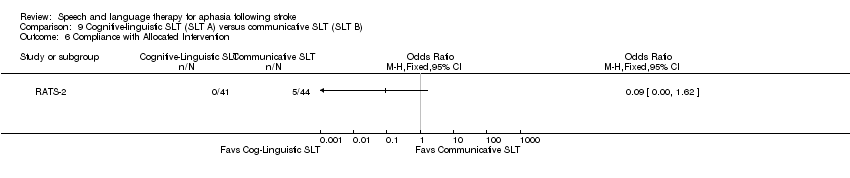

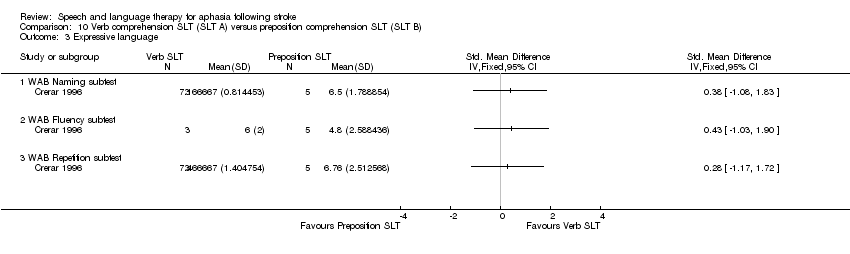

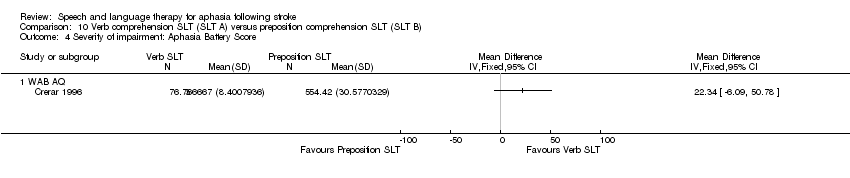

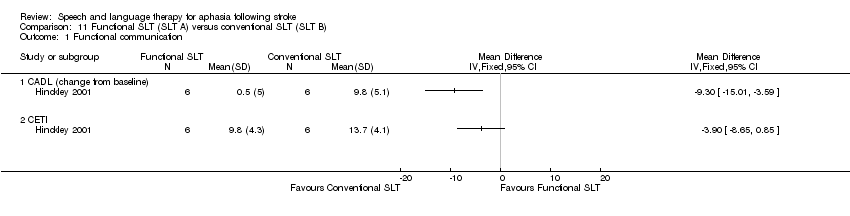

We included 25 trials (910 randomised participants) in this section (Bakheit 2007; Crerar 1996; Denes 1996; Di Carlo 1980; Drummond 1981; Hinckley 2001; Leal 1993; Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1982ii; Lincoln 1984b; Meikle 1979; Meinzer 2007; ORLA 2006; ORLA 2010; Prins 1989; Pulvermuller 2001; RATS; RATS‐2; Shewan 1984i; Smith 1981iii; Van Steenbrugge 1981; VERSE 2011; Wertz 1981; Wertz 1986iii; Yao 2005iii). Four trials (Bakheit 2007; ORLA 2006; Prins 1989; Shewan 1984) also reported additional groups but these participants were not adequately randomised to the groups and so they have been excluded from this review.

A wide range of SLT interventions were reported including functional SLT (Hinckley 2001), intensive SLT (Bakheit 2007; Denes 1996; ORLA 2006; Smith 1981iii; VERSE 2011), volunteer‐facilitated SLT (Meikle 1979; Meinzer 2007; Leal 1993; Wertz 1986iii), computer‐facilitated SLT (ORLA 2010), group SLT (Pulvermuller 2001; Wertz 1981; Yao 2005iii) and task‐specific SLT (Drummond 1981; Prins 1989; Pulvermuller 2001; Shewan 1984i; Van Steenbrugge 1981) compared with a more conventional SLT model. Other trials compared verb and preposition therapies (Crerar 1996), semantic and phonological therapies (RATS), cognitive‐linguistic and communicative approaches (RATS‐2), filmed programmed instructions with non‐programmed activity (Di Carlo 1980) or programmed instruction with a placebo (Lincoln 1984b).

The duration of participants' aphasia ranged from less than one week (VERSE 2011) up to one month (Leal 1993; Shewan 1984i; Smith 1981iii; Wertz 1981), two months (Bakheit 2007; RATS‐2), six months (Denes 1996; RATS; Wertz 1986iii), 10 months (Lincoln 1982i), one year (Lincoln 1984b), two years (Drummond 1981), three years (Lincoln 1982ii), five years (Van Steenbrugge 1981; Meikle 1979), six years (Di Carlo 1980; Meinzer 2007), eight years (Hinckley 2001), 11 years (Crerar 1996), 13 years (ORLA 2006), 17 years (Prins 1989), 19 years (Pulvermuller 2001) or 21 years (ORLA 2010) after the onset of aphasia. Yao 2005iii did not report the duration of their participants' aphasia.

Therapy was provided daily (Yao 2005iii) for up to two hours (Crerar 1996), three hours (Meinzer 2007; Pulvermuller 2001) or weekly for up to 30 minutes (Drummond 1981), one hour (Lincoln 1984b), 1.5 hours (Lincoln 1982i; Smith 1981iii), two hours (Prins 1989; Van Steenbrugge 1981), three hours (Di Carlo 1980; RATS; Leal 1993; Shewan 1984i), four hours (Meikle 1979; Smith 1981iii), five hours (Bakheit 2007; Denes 1996; RATS‐2), seven hours (VERSE 2011), eight hours (Wertz 1981), 10 hours (ORLA 2006; Wertz 1986iii) or 20 hours (Hinckley 2001). The duration of therapy ranged from two weeks (Drummond 1981; Meinzer 2007), three weeks (Crerar 1996), four weeks (Lincoln 1984b; VERSE 2011; Yao 2005iii), five weeks (Hinckley 2001; Pulvermuller 2001), six weeks (ORLA 2006), eight weeks (Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1982ii), nine weeks (Van Steenbrugge 1981), 12 weeks (Bakheit 2007; Wertz 1986iii), 30 weeks (Di Carlo 1980), five months (Prins 1989), up to six months (Denes 1996; Leal 1993; RATS‐2), nine months (RATS), 10 months (Wertz 1981), one year (Shewan 1984i; Smith 1981iii) or two years (Meikle 1979). The therapy intervention varied across participants in ORLA 2010 with each receiving 24 hours of therapy over a mean treatment duration of 12.62 weeks (range 6 to 22 weeks).

There was a wide range of outcome measures used in this comparison including measures of functional communication, receptive language, expressive language, severity of impairment and psychosocial impact. Follow‐up assessments were carried out at six weeks (Wertz 1986iii), three months (Bakheit 2007; Yao 2005iii) and six months (VERSE 2011) following treatment.

Excluded studies

We excluded 30 studies, which incorporates 14 new exclusions (Breitenfeld 2005; Cherney 2010; Gu 2003; Hagen 1973; Hinckley 2005; Holmqvist 1998; Kurt 2008; Liu 2006a; Luo 2008; Marshall 2001; Thompson 2010; Vines 2007; Weiduschat 2011; Zhang 2004). Reasons for exclusion were primarily due to inadequate randomisation and the unavailability of aphasia specific data (see details in the Characteristics of excluded studies table).

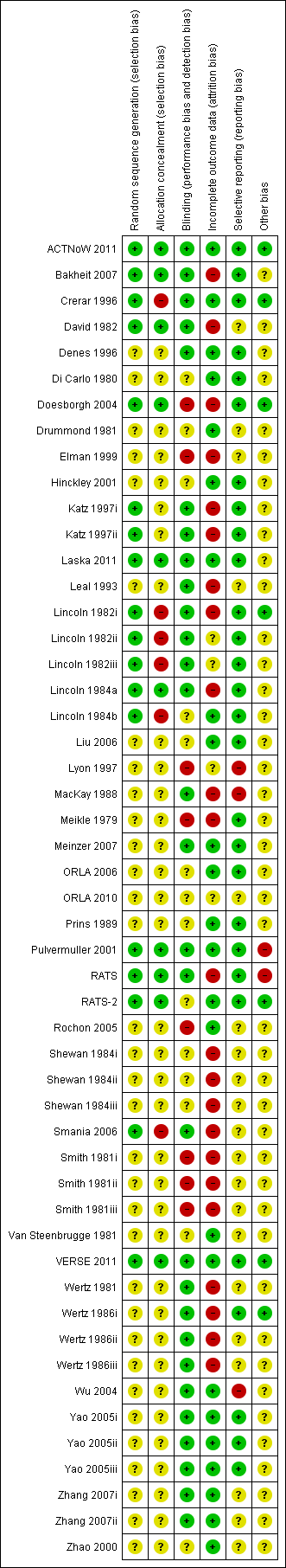

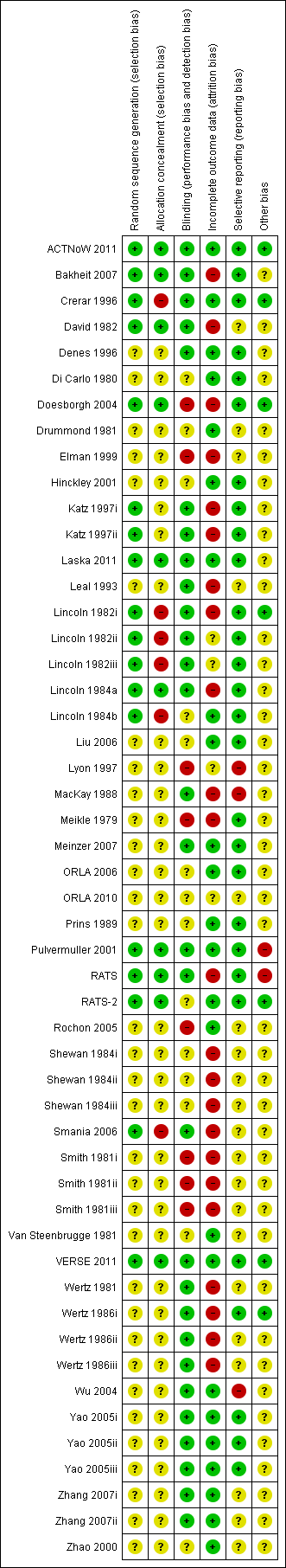

Risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently reviewed the methodological quality of the included studies and resolved disagreements through discussion. Details can be found in the 'Risk of bias' tables for each of the trials in the Characteristics of included studies table.

The number of participants randomised across trials included in the review ranged from five to 327 participants. Four comparisons randomised 10 participants or fewer (Crerar 1996; Drummond 1981; Rochon 2005; Van Steenbrugge 1981), 11 randomised between 11 and 20 participants (Denes 1996; Di Carlo 1980; Doesborgh 2004; Hinckley 2001; Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1982ii; Lincoln 1982iiiLincoln 1984b; Meinzer 2007; ORLA 2006; Pulvermuller 2001), 15 randomised up to 50 participants (Elman 1999; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Liu 2006; Lyon 1997; Meikle 1979; ORLA 2010; Prins 1989; Shewan 1984iii; Smania 2006; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Smith 1981iii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii), 15 randomised between 51 and 100 participants (Bakheit 2007; Leal 1993; MacKay 1988; RATS; RATS‐2; Shewan 1984i; Shewan 1984ii; VERSE 2011; Wertz 1981; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wertz 1986iii; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Yao 2005iii), two randomised between 101 and 150 (Laska 2011; Zhao 2000) and four randomised more than 150 participants (ACTNoW 2011; David 1982; Lincoln 1984a; Wu 2004) (see Table 1).

Of the 51 randomised comparisons, only 25 listed both inclusion and exclusion criteria. Details of exclusion criteria were unavailable for an additional 23 trials (Crerar 1996; Denes 1996; Di Carlo 1980; Hinckley 2001; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Lincoln 1984b; Lyon 1997; MacKay 1988; Meikle 1979; ORLA 2006; Prins 1989; Rochon 2005; Van Steenbrugge 1981; Wertz 1981; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wertz 1986iii; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Yao 2005iii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were unavailable for three trials (Drummond 1981; Wu 2004; Zhao 2000). For details, see the Characteristics of included studies table.

Suitable statistical data for communication outcomes were only available for 39 of the 51 trials. Appropriate statistical data for communication outcomes were not provided or could not be extracted in the remaining 13 trials (Drummond 1981; Elman 1999; Leal 1993; Lyon 1997; MacKay 1988; Shewan 1984i; Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii; Smania 2006; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Smith 1981iii; Wu 2004). All but one of these trials (Wu 2004) contributed data on the trial dropouts or withdrawals. Psychosocial data were available for two trials (ACTNoW 2011; Lincoln 1984a).

There was a wide range of variation in the descriptions of the SLT interventions. Most reported the use of a conventional SLT approach or described an intervention, which reflects clinical practice where the therapist was responsible for design and content of the treatment delivered. Other more prescriptive SLT interventions were also evaluated (including volunteer‐facilitated therapy, intensive therapy, constraint‐induced language therapy for example) and these will be detailed further in later sections.

Thirty‐five trials reported similar groups at baseline (ACTNoW 2011; Bakheit 2007; Crerar 1996; Denes 1996; Di Carlo 1980; Doesborgh 2004; Drummond 1981; Elman 1999; Hinckley 2001; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Laska 2011; Leal 1993; Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1982ii; Lincoln 1982iii; Lincoln 1984a; Liu 2006; Meikle 1979; ORLA 2006; ORLA 2010; Rochon 2005; Shewan 1984i; Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii; Smania 2006; Smith 1981iii; Van Steenbrugge 1981; Wertz 1981; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wertz 1986iii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii; Zhao 2000). Comparison between the groups at baseline was unclear in seven trials (Lincoln 1984b; Lyon 1997; MacKay 1988; Wu 2004; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Yao 2005iii). For nine trials the groups differed despite randomisation in relation to their time post‐onset (Pulvermuller 2001), the severity of their stroke (VERSE 2011), severity of their aphasia (Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii), gender (RATS‐2) and age (David 1982; RATS; Meinzer 2007; Prins 1989). In Meikle 1979 the participants that were allocated to SLT received more weeks of the intervention than the volunteer‐facilitated group (P = 0.01).

Allocation

Details of the method of generating the randomisation sequence were only available for 17 of the 51 trials. Ten used random numbers tables (Bakheit 2007; David 1982; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1982ii; Lincoln 1982iii; Lincoln 1984a; Lincoln 1984b; Smania 2006), six were computer‐generated (ACTNoW 2011; Doesborgh 2004; Pulvermuller 2001; RATS; RATS‐2; VERSE 2011) and one drew lots (Crerar 1996). The remaining 34 trials stated that participants were randomly allocated but did not report any further details. Five trials described stratifying participants by type and severity of aphasia (ACTNoW 2011; Leal 1993; Shewan 1984i; Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii) and two stratified by recruitment site (ACTNoW 2011; RATS‐2).

Details of the allocation concealment were available for 16 of the 51 trials. Nine used sequentially numbered sealed envelopes or similar methods of allocation and were considered to be adequately concealed (ACTNoW 2011; Bakheit 2007; David 1982; Doesborgh 2004; Laska 2011; Lincoln 1984a; RATS; RATS‐2; VERSE 2011). Four described using an allocation service that was external to the trial team (ACTNoW 2011; Laska 2011; RATS‐2; VERSE 2011). Two described a trialist‐led allocation method that inadequately concealed allocation to the groups (Crerar 1996; Smania 2006).

Blinding

Due to the nature of SLT it is difficult to blind either the patient or person carrying out the intervention. However, blinding of the outcome assessor is possible and should be in place to avert detection bias. More than half of the included trials (33/51) reported blinding of outcome assessors (ACTNoW 2011; Bakheit 2007; Crerar 1996; Denes 1996; RATS; RATS‐2; Laska 2011; Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1982ii; Lincoln 1982iii; Lincoln 1984a; MacKay 1988; Meinzer 2007; ORLA 2010; Pulvermuller 2001; Shewan 1984i; Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii; Smania 2006; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Smith 1981iii; VERSE 2011; Wertz 1981; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wertz 1986iii; Wu 2004; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Yao 2005iii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii). In other cases blinding was partially in place. The method of assessment ensured blinding in some of the outcome measures for three trials (Crerar 1996; Lincoln 1984b; ; RATS‐2), while three additional trials (Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Rochon 2005) ensured blinding of a second assessor who checked a proportion of measurements scores. Two trial reports (ACTNoW 2011; David 1982) acknowledged the possibility that measures may have been confounded to some extent by indications from the participants being assessed as to which group they were attending. This is likely to have occurred across several trials. Blinding, however, was unclear for 11 trials (Di Carlo 1980; Doesborgh 2004; Drummond 1981; Hinckley 2001; Leal 1993; Liu 2006; ORLA 2006; Prins 1989; Rochon 2005; Van Steenbrugge 1981; Zhao 2000) and considered inadequate in seven trials (Doesborgh 2004; Elman 1999; Lyon 1997; Meikle 1979; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Smith 1981iii).

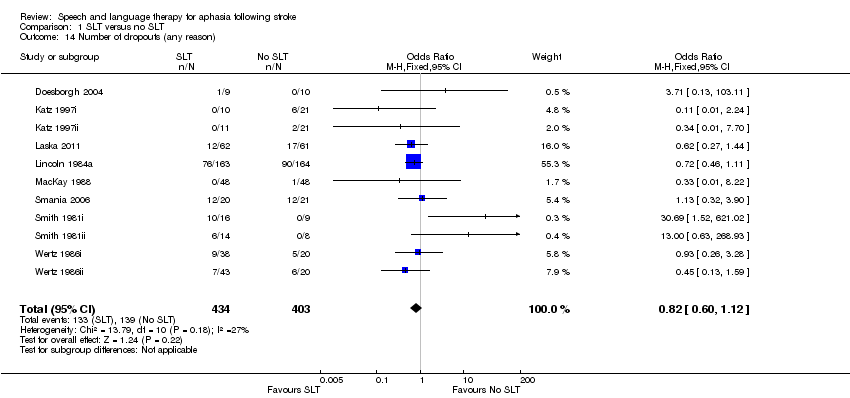

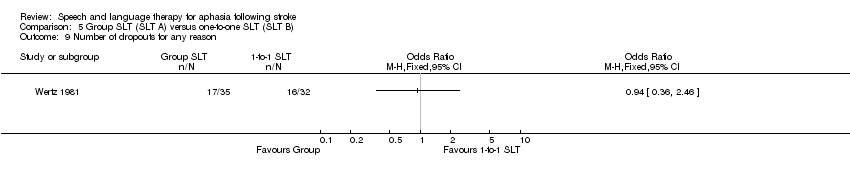

Incomplete outcome data

Overall, 21% of the 2518 participants randomised across the 51 comparisons included in this review withdrew from the intervention or were lost to follow‐up (437 participants plus 92 at follow‐up). Of the 1414 participants in the SLT versus no SLT comparison, 226 (16%) withdrew from the treatment phase of the studies (114 from the SLT interventions and 112 from the 'no SLT' allocation). In addition, 52 participants were lost during the follow‐up assessment phase (19 withdrawing from the SLT groups and 27 from the 'no SLT' groups).The trials that compared SLT with social support and stimulation randomised a total of 432 participants but 105 participants (24%) were lost during the treatment phase (40 from the SLT group and 65 from the social support groups). Twenty‐five additional participants were not included in the follow‐up (David 1982; Elman 1999). The final comparison of SLT A versus SLT B involved 910 randomised participants. A total of 130 participants (14%) withdrew from these trials during the treatment phase with an additional six withdrawing from the follow‐up phase. Across the review, five participants were reported to have withdrawn from a trial but it was unclear which group(s) those participants were allocated to (Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Smith 1981iii). Participants in Meikle 1979 remained in the trial until two successful estimations on an outcome measure showed no appreciable improvement, participants requested withdrawal or until the end of the trial, however no further details were given. Where available, details of dropouts are presented in Table 2.

| Study ID | Dropouts by intervention | Reasons | Follow‐up | Reasons |

| Conventional: 8 Social support: 20 | Conventional: 4 died, 3 declined, 1 post‐randomisation exclusion, 2 non‐study SLT Social support: 7 died, 12 declined, 1 post‐randomisation exclusion, 18 non‐study SLT | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Intensive: 16 | Intensive: 2 died, 14 withdrew | Intensive: 4 | Not reported | |

| Conventional: 23 | Conventional: 4 died, 5 new stroke, 2 self discharge, 5 illness, 3 moved, 4 other | Conventional: 11 | Not reported | |

| Computer‐mediated: 1 | Computer‐mediated: 1 illness | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Conventional: 2 | Conventional: 1 transport, 1 time constraints, | Conventional: 0 | ||

| Computer‐mediated: 0 | Prolonged illness, new stroke, death | Computer‐mediated: 0 | ||

| Computer‐mediated: 0 | Prolonged illness, new stroke, death | Computer‐mediated: 0 | ||

| SLT: 3 No SLT: 6 | SLT: 1 death, 2 illness No SLT: 3 declined, 3 illness | At 6 months SLT: 9 No SLT: 6 | SLT: 4 death, 2 declined, 3 illness No SLT: 6 death | |

| Conventional: 21 | Conventional: 2 death, 3 new stroke, 3 transport, 4 declined, 2 moved, 5 illness, 2 transfer | Conventional: 0 | ||

| Social support: ? | Homesickness, illness | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Social support: ? | Homesickness, illness | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Social support: ? | Homesickness, illness | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Conventional: 78 | Death, refused, illness, recovered, unsuitable, relocated | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Volunteer‐facilitated: 0 | Not reported | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Conventional: 0 | Conventional: 0 | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Semantic: 6 | Semantic: 4 received < 40 hours treatment, 2 severe neurological illness | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Cognitive linguistic: 4 Communicative: 6 | Cognitive linguistic: 3 illness, 1 refusal by therapist Communicative: 1 illness, 5 declined | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Language orientated: 6 | Language orientated: 1 death, 2 relocation, 3 withdrew | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Language orientated: 6 | Language orientated: 1 death, 2 relocation, 3 withdrew | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Conventional: 1 | Conventional: 1 death | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Conventional: 5 | Conventional: 3 uncooperative, 2 illness | Conventional: 7 | Conventional: 3 illness, 4 refused | |

| Intensive: 6 | Reasons not detailed | Intensive: 4 | Not reported | |

| Conventional: 2 | Reasons not detailed | Conventional: 4 | Not reported | |

| Intensive: 6 | Reasons not detailed | Intensive: 4 | Not reported | |

| Intensive: 7 Conventional: 1 | Intensive: 4 declined, 2 discharged early, 1 died. Conventional: 1 declined | Intensive: 4 Conventional: 2 | Intensive: 4 refused Conventional: 1 refused, 1 death | |

| Group: 17 | 22 self‐discharged (return home or declined to travel), 4 illness, 2 stroke, 3 died, 2 returned to work | No follow‐up | N/A | |

| Conventional: 7 | Illness, new stroke | Conventional: 2 | Illness, new stroke | |

| Volunteer‐facilitated: 6 | Illness, new stroke | Volunteer‐facilitated: 1 | Illness, new stroke | |

| Conventional: 7 | Illness, new stroke | Conventional: 2 | Illness, new stroke |

ANELT: Amsterdam‐Nijmegen Everyday Language Test

SLT: speech and language therapy

Selective reporting

Recruitment and retention of stroke rehabilitation trial participants is known to be a challenge and the trials in this review were no exception. However, seven trials only reported data (including demographic data) from participants that remained in the trial at the end of treatment or at follow‐up. David 1982 reported data from 133 of 155 randomised participants, Doesborgh 2004 reported 18 of 19 randomised participants, Katz 1997i reported 36 of 42 randomised participants, Katz 1997ii reported 40 of 42 randomised participants, Lincoln 1984a reported 191 of 327 randomised participants, MacKay 1988 reported 95 of 96 randomised participants and Smania 2006 reported 33 of 41 randomised participants. Six trials reported using ITT analysis (ACTNoW 2011; Bakheit 2007; Laska 2011; RATS; RATS‐2; VERSE 2011) but not all participants appeared to be included in the final analyses within two trials (Bakheit 2007; RATS). In addition, 21 trials that reported participants that had dropped out did not report using ITT analysis (David 1982; Doesborgh 2004; Elman 1999; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Leal 1993; Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1984a; MacKay 1988; Meikle 1979; Shewan 1984i; Shewan 1984ii; Shewan 1984iii; Smania 2006; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Smith 1981iii; Wertz 1981; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wertz 1986iii). All randomised participants were included in the final analyses for the remaining 24 trials.

Other potential sources of bias

Co‐interventions were reported by some trialists that compared the effects of SLT with no SLT. Two groups that received SLT also received acupuncture (Liu 2006; Zhang 2007ii). Some participants in Doesborgh 2004 also received psychosocial group therapy and some (or all) of the participants reported in Smith 1981i may have benefited from other intensive treatment as part of the larger multidisciplinary stroke trial. In both cases the number and allocation of the participants and specific details of the co‐intervention were unavailable. In other cases, not all participants received the planned number of treatment sessions (Laska 2011; Lincoln 1984a; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii).

Similarly, seven trials that compared two different approaches with SLT provision reported that not all participants received the planned number of treatment sessions (Bakheit 2007; Lincoln 1982i; Lincoln 1982ii;Meikle 1979;RATS‐2; Smith 1981iii; VERSE 2011). Meikle 1979 reported that five of the 16 participants receiving conventional SLT missed up to half of their possible treatment. Four trials comparing a high intensity SLT with a low intensity SLT also reported difficulties providing intensive SLT interventions as planned. Bakheit 2007 reported that only 13 of the 51 participants received 80% or more of the planned intensive intervention. Smith 1981iii reported that participants allocated to intensive therapy only received an average of 21 hours of therapy compared to the planned minimum of 50 hours during the first three months. Such difficulties in maintaining a clear distinction between the two treatment groups has significant implications when evaluating the results and considering the clinical implications of such treatment regimens. Similarly, VERSE 2011 found that six individuals did not reach the intensive SLT intervention target of 2.5 hours but they also reported that resource limitations in the conventional acute care service meant that 23 individuals in the usual care group failed to receive the maximum once weekly therapy, as allocated. Difficulty maintaining a consistent intensity of treatment across two treatment arms was reported by ORLA 2010 with some participants choosing to have more of the allocated 24 treatment sessions per week than others.

Though all the speech and language therapists in Hinckley 2001 were trained in the characteristics of the two treatment approaches being compared, treatment review processes were in place to ensure any possible risk of overlap in therapy approach was minimised. ACTNoW 2011 employed a similar monitoring approach to ensure fidelity to the planned interventions. Data from three randomised comparisons (Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Smith 1981iii) were subgroups of participants with aphasia extracted from within a larger trial examining models of stroke care. Being part of a larger stroke trial may have affected their levels of fatigue and ability to participate fully in the SLT intervention. The main trial described the inclusion of 20 participants with mild dementia but it is unclear whether any of these individuals were included in the aphasia‐specific data.

Effects of interventions

The results of this review are presented below within the three comparisons: (1) SLT versus no SLT, (2) SLT versus social support and stimulation, and (3) SLT A versus SLT B. Where data availability permitted, results from meta‐analyses are also reported. As described in the Measures of treatment effect section, we extracted the final value scores for inclusion within this review whenever possible. Final value scores were available for 23 of the 51 trials and these have been included within the review. Only change‐from‐baseline data were available for an additional three trials (Denes 1996; Hinckley 2001; RATS). Where change‐from‐baseline data are used they are clearly marked and the data are not pooled within the meta‐analyses with final value scores.

Comparison 1: SLT versus no SLT

A total of 1414 participants were randomised across 19 randomised comparisons that contrasted SLT with no SLT (Doesborgh 2004; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Laska 2011; Lincoln 1984a; Liu 2006; Lyon 1997; MacKay 1988; Smania 2006; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Wu 2004; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii; Zhao 2000). Reporting of age and other descriptions of the participants across trials varied, making it difficult to give an overview of the participants involved in this comparison. Only five trials reported age ranges, spanning 38 to 94 years of age (Laska 2011; Lincoln 1984a; Lyon 1997; Smania 2006; Wu 2004), while others reported participants' mean age or age bands. Details can be found in Table 1. Thirteen trials gave an indication of the length of time since participants had experienced the onset of their aphasia: the widest range of time post‐onset reported spanned two to 36 months (Smania 2006). The shortest mean length of time since the onset of participants' aphasia was three days (range two to four days) (Laska 2011). Severity of aphasia was reported by 11 trials (Doesborgh 2004; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Laska 2011; Liu 2006; Smith 1981i; Smith 1981ii; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii), although two additional trials provided some indication of severity of impairment (Lyon 1997; Smania 2006).

Among the SLT interventions compared to a 'no SLT' group were interventions considered to be conventional SLT (Liu 2006; Smania 2006; Smith 1981ii; Wertz 1986i; Wu 2004; Yao 2005ii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii; Zhao 2000), computer‐mediated SLT (Doesborgh 2004; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii), group SLT (Yao 2005i), functional SLT (Lyon 1997), intensive SLT (Laska 2011; Smith 1981i), language enrichment therapy (Laska 2011), SLT plus operant training (Lincoln 1984a) and volunteer‐facilitated SLT (MacKay 1988; Wertz 1986ii). We planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis on trials that involved the provision of SLT by non‐speech and language therapists (Liu 2006; MacKay 1988; Wertz 1986ii; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii; Zhao 2000) but because of the present availability of data within each outcome it was not useful to undertake this analysis.

Appropriate summary data for communication outcomes (allowing inclusion in the meta‐analyses) were available for 13 of the 19 trials (Doesborgh 2004; Katz 1997i; Katz 1997ii; Liu 2006; Lincoln 1984a; Smania 2006; Wertz 1986i; Wertz 1986ii; Yao 2005i; Yao 2005ii; Zhang 2007i; Zhang 2007ii; Zhao 2000). In addition, Lincoln 1984a also reported statistical data for psychosocial outcomes. Suitable summary data were not reported (or available on request) for the remaining five trials (Lyon 1997; MacKay 1988;Smith 1981i;Smith 1981ii;Wu 2004). Where data for this comparison were available they are presented below in relation to the following: (1) functional communication, (2) receptive language, (3) expressive language, (4) severity of impairment, (5) psychosocial, (6) number of dropouts, (7) compliance with allocated intervention and (8) economic outcomes.

1. Functional communication