Cirugía de mama por cáncer de mama metastásico

Resumen

Antecedentes

El cáncer de mama metastásico es una enfermedad incurable, pero las pacientes con enfermedad metastásica en la actualidad viven más tiempo. La cirugía para extraer el tumor primario se asocia con una mayor supervivencia en otros tipos de cáncer metastásico. La cirugía de mama no es el tratamiento estándar para la enfermedad metastásica; sin embargo, varios estudios retrospectivos recientes han indicado que la cirugía de mama podría aumentar la supervivencia de las pacientes. Estos estudios tienen limitaciones metodológicas que incluyen el sesgo de selección. Una revisión sistemática que analice todos los ensayos controlados aleatorios que abordan los efectos beneficiosos y perjudiciales potenciales de la cirugía de mama es ideal para responder esta pregunta.

Objetivos

Evaluar los efectos de la cirugía de mama en las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico.

Métodos de búsqueda

Se realizaron búsquedas utilizando los términos MeSH 'breast neoplasms', 'mastectomy', y 'analysis, survival' en las siguientes bases de datos: registro especializado del Grupo Cochane de Cáncer de Mama (Cochrane Breast Cancer Specialised Register), CENTRAL, MEDLINE (con PubMed) y en Embase (con OvidSP) el 22 febrero 2016. También se hicieron búsquedas en ClinicalTrials.gov (22 febrero 2016) y en la WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (24 febrero 2016). También se realizó una búsqueda adicional en las actas de congresos de la American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) en julio de 2016 que incluyó la verificación de referencias, la búsqueda de citas y el contacto con los autores de los estudios para identificar estudios adicionales.

Criterios de selección

Los criterios de inclusión fueron ensayos controlados aleatorios en pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico al momento del diagnóstico inicial que compararon cirugía de mama más tratamiento sistémico versus tratamiento sistémico solo. Los resultados primarios fueron supervivencia general y calidad de vida. Los resultados secundarios fueron supervivencia libre de progresión (control local y a distancia), supervivencia específica del cáncer de mama y toxicidad del tratamiento local.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Dos autores de la revisión realizaron de forma independiente la selección de los ensayos, la extracción de los datos y la evaluación del "riesgo de sesgo" (con el uso de la herramienta Cochrane "Riesgo de sesgo"), y un tercer autor de la revisión las verificó. Se utilizó la herramienta GRADE para evaluar la calidad del cuerpo de evidencia. Se utilizó el cociente de riesgos (CR) para medir el efecto del tratamiento para los resultados dicotómicos y el cociente de riesgos instantáneos (CRI) para los resultados de tiempo transcurrido hasta el evento. Se calcularon los intervalos de confianza (IC) del 95% para estas medidas. Se utilizó el modelo de efectos aleatorios debido a la heterogeneidad clínica o metodológica, o ambas, esperada entre los estudios incluidos.

Resultados principales

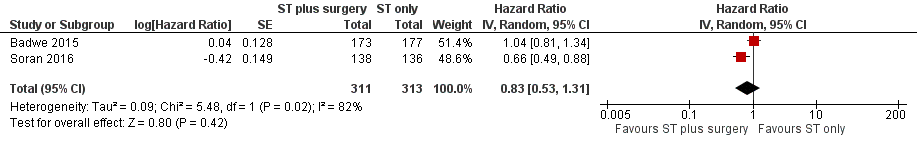

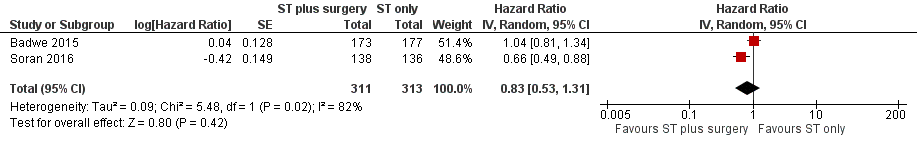

Se incluyeron dos ensayos con 624 mujeres en la revisión. No está claro si la cirugía de mama mejora la supervivencia general, ya que la calidad de la evidencia se consideró muy baja (CRI 0,83; IC del 95%: 0,53 a 1,31; dos estudios; 624 mujeres). Los dos estudios no informaron la calidad de vida. La cirugía de mama puede mejorar la supervivencia libre de progresión local (CRI 0,22; IC del 95%: 0,08 a 0,57; dos estudios; 607 pacientes; evidencia de baja calidad), aunque probablemente empeoró la supervivencia libre de progresión a distancia (CRI 1,42; IC del 95%: 1,08 a 1,86; un estudio; 350 pacientes; evidencia de calidad moderada). Los dos estudios incluidos no midieron la supervivencia específica del cáncer de mama. La toxicidad del tratamiento local se informó mediante la mortalidad a los 30 días y no pareció diferir entre los dos grupos (CR 0,99; IC del 95%: 0,14 a 6,90; un estudio; 274 pacientes; evidencia de baja calidad).

Conclusiones de los autores

Según la evidencia existente de dos ensayos clínicos aleatorios, no es posible establecer conclusiones definitivas sobre los efectos beneficiosos ni los riesgos de la cirugía de mama asociados con el tratamiento sistémico en las pacientes con diagnóstico de cáncer de mama metastásico. Hasta que concluyan los ensayos clínicos en curso, la decisión de realizar la cirugía de mama en estas pacientes se debe individualizar y compartir entre el médico y la paciente, así como considerar los riesgos potenciales, los efectos beneficiosos y los costos de cada intervención.

PICOs

Resumen en términos sencillos

Cirugía de mama por cáncer de mama metastásico

Pregunta de la revisión

En pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico (cuando el cáncer se ha propagado a otras partes del cuerpo), ¿cuál es la efectividad de la cirugía de mama (mastectomía: extracción de toda la mama incluido el pezón y la aréola, o tumorectomía: extracción del tumor y el tejido de la mama alrededor del tumor pero con preservación del pezón y la aréola) en combinación con el tratamiento médico (como quimioterapia y terapia hormonal) en comparación con tratamiento médico solo?

Antecedentes

El cáncer de mama metastásico se considera una enfermedad incurable con pronóstico deficiente, aunque algunas pacientes pueden vivir muchos años. Tradicionalmente solo se trata con tratamiento médico. La cirugía de mama se consideraba paliativa y se realizaba solo para aliviar los síntomas como la hemorragia local, la infección o el dolor. Con el desarrollo de fármacos nuevos, las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico viven más tiempo y la cirugía de mama podría beneficiar a este grupo de pacientes. Los datos retrospectivos (es decir, datos de tipos de estudios, diferentes de los ensayos controlados aleatorios, que tienen una mayor probabilidad de presentar sesgo) indican que la cirugía de mama podría mejorar la supervivencia de las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico.

Características de los estudios

La evidencia está actualizada hasta febrero 2016. Se incluyeron solamente los ensayos clínicos aleatorios, ya que se consideran el mejor tipo de estudio científico para responder las interrogantes acerca del tratamiento, que compararon la supervivencia de las pacientes sometidas a cirugía de mama combinada con tratamiento médico versus tratamiento médico solo. Se identificaron e incluyeron dos ensayos controlados aleatorios que incluyeron un total de 624 mujeres: 311 pacientes se sometieron a cirugía de mama más tratamiento médico y 313 pacientes solo recibieron tratamiento médico.

Resultados clave

Los autores de la revisión no están seguros con respecto a si la cirugía de mama mejora la supervivencia general, ya que la calidad de la evidencia se consideró muy baja. Los estudios incluidos no informaron ninguna información relacionada con la calidad de vida. La cirugía de mama puede mejorar el control de la enfermedad local pero probablemente empeora el control en sitios a distancia. Los dos estudios incluidos no midieron la supervivencia específica del cáncer de mama. La toxicidad del tratamiento local pareció ser la misma en el grupo sometido a cirugía de mama combinada con tratamiento médico y en el grupo que solo recibió tratamiento médico.

¿Qué significa esto?

No es posible establecer conclusiones definitivas acerca de los efectos beneficiosos de la cirugía de mama asociada con tratamiento médico en pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico. La decisión de realizar la cirugía en dichos casos se debe individualizar y compartir entre el médico y la paciente, y considerar los riesgos y los efectos beneficiosos potenciales de esta elección. La inclusión en la próxima actualización de esta revisión de los resultados de los ensayos en curso que incluyen a pacientes con estas características ayudará a reducir las incertidumbres existentes.

Conclusiones de los autores

Summary of findings

| Breast surgery plus systemic treatment compared to systemic treatment for metastatic breast cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: metastatic breast cancer | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with systemic treatment | Risk with breast surgery plus systemic treatment | |||||

| Overall survival at 2 years Follow‐up: range 23 months to 40 months | Study population | HR 0.83 | 624 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | The estimates for the control group are based upon an average of the estimates from Badwe 2015 and Soran 2016. | |

| 511 per 1000 | 448 per 1000 | |||||

| Quality of life | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Local PFS at 2 years Follow‐up: range 23 months to 40 months | Study population | HR 0.22 | 607 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The estimates for the control group are based upon an average of the estimates from Badwe 2015 and Soran 2016. | |

| 500 per 1000 | 141 per 1000 | |||||

| Distant PFS at 2 years Follow‐up: 23 months | Study population | HR 1.42 | 350 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | The estimates for the control group are based upon the estimates from Badwe 2015. | |

| 548 per 1000 | 676 per 1000 | |||||

| Breast cancer‐specific survival | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Toxicity from local therapy Follow‐up: 40 months | Study population | RR 0.99 | 274 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The estimates for the control group are based upon the estimates from Soran 2016. | |

| 15 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1In Soran 2016, trial random sequence generation and allocation concealment were unclear. Downgraded one level. | ||||||

Antecedentes

Descripción de la afección

El cáncer de mama es uno de los cánceres que ocurren con mayor frecuencia en las mujeres. Se calcula que 1 670 000 nuevos casos de cáncer de mama se diagnostican en todo el mundo por año, lo que representa el 25% de todos los cánceres diagnosticados (GLOBOCAN 2012). Entre el 20% y el 30% de las pacientes con cáncer de mama desarrollará metástasis sincrónicas o metacrónicas a distancia, lo que provoca de 400 000 a 500 000 muertes por año en todo el mundo (Caudle 2012). Al momento del diagnóstico inicial el 3,5% de todas las pacientes con cáncer de mama en los Estados Unidos ya presentan enfermedad metastásica a distancia, y este porcentaje es mayor en los países de ingresos bajos y medios (Khan 2002). Lo anterior significa que cada año cerca de 50 000 mujeres recibirán un diagnóstico inicial de cáncer de mama metastásico (Ly 2010).

Aunque el cáncer de mama metastásico se considera una enfermedad incurable con un pronóstico deficiente, actualmente las pacientes con este diagnóstico viven más tiempo, y la tasa de supervivencia a los cinco años ha aumentado del 10% en 1970 a cerca del 40% en las pacientes tratadas después de 1995 (Giordano 2004). Las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico tratadas entre 1995 y 2002 tuvieron un riesgo 18% menor de muerte que las pacientes tratadas entre 1985 y 1994 (Ernst 2007). La mediana de la supervivencia general ha mejorado desde 20 meses (1988 a 1991) hasta 26 meses (2007 a 2011) en otras series (Thomas 2015). El aumento en la supervivencia también aumenta el riesgo de síntomas locales en las pacientes que no se han sometido a cirugía de mama para extraer el tumor primario.

El tratamiento del cáncer de mama también puede tener una repercusión negativa sobre la calidad de vida de la paciente y se asocia con temores como el desarrollo futuro de la enfermedad en las hijas, la pérdida del trabajo y la reducción del deseo sexual (Ferrel 1997). Un estudio que evaluó la calidad de vida de las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico mostró que dieron mayor importancia a los tratamientos que prolongaron la supervivencia libre de enfermedad que a los tratamientos que prolongaron la supervivencia (Hurvitz 2013). Aunque la mayoría de las supervivientes de cáncer de mama consideran su calidad de vida como positiva, a menudo se quejan de problemas de adaptación y psicosociales en lugar de déficits físicos (Sales 2001). El equipo multidisciplinario se debe familiarizar con estos problemas para ofrecer un mejor programa de rehabilitación a estas pacientes.

Descripción de la intervención

Históricamente las pacientes diagnosticadas con cáncer de mama metastásico no se trataban quirúrgicamente y solo recibían tratamiento sistémico (Bermas 2009). Durante la última década estas mujeres han vivido más tiempo. Se consideraba que la resección quirúrgica del tumor primario era paliativa y se realizaba solo para aliviar síntomas como la hemorragia, la infección o el dolor. Este enfoque terapéutico se basaba en la premisa de que el tratamiento local del cáncer de mama metastásico no mejoraba la supervivencia general. Sin embargo, en pacientes con carcinoma de células renales metastásico, dos ensayos controlados aleatorios prospectivos mostraron que la cirugía local más el tratamiento sistémico dio lugar a tasas de supervivencia más prolongada que el tratamiento sistémico solo (Flanigan 2001; Mickisch 2001). Otro estudio reciente mostró que la cirugía local fue beneficiosa en los pacientes con cáncer colorrectal metastásico (Anwar 2012). Este hecho ha dado lugar a formular la hipótesis de que el tratamiento local en el cáncer de mama metastásico también puede mejorar la supervivencia.

En años recientes, la resección quirúrgica electiva del tumor de mama primario antes de la aparición de síntomas locales se ha generalizado más. Morrogh y colegas informaron un aumento significativo del número de pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico que se sometieron a cirugía de mama entre 2000 y 2005 en comparación con 1995 y 2000 (Morrogh 2008). Otro estudio que utilizó la base de datos American Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) mostró una disminución en la cirugía de mama realizada en las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico del 67,8% en 1988 al 25,1% en 2011 (Thomas 2015).

La intervención consiste en la extracción quirúrgica del tumor de mama, ya sea por cirugía conservadora (tumorectomía) o radical (mastectomía). El tratamiento quirúrgico se complementa con la evaluación de la enfermedad axilar mediante la técnica del ganglio linfático centinela o la linfadenectomía. La radioterapia torácica puede formar parte del tratamiento locorregional.

De qué manera podría funcionar la intervención

Las células cancerosas pueden migrar a otros órganos, iniciar la división celular y alterar el microambiente tumoral que favorece el crecimiento de focos metastásicos. Debido a que el tumor de mama primario puede ser un reservorio de células madre de cáncer, su extracción puede reducir la probabilidad de desarrollar nuevos sitios metastásicos (Bermas 2009). Además, el tumor primario puede secretar factores de crecimiento como el factor de crecimiento tumoral (FCT)‐β, que puede enviar señales que favorecen la implantación y el crecimiento de los sitios metastásicos (Karnoub 2007). Estudios en modelos animales indican que la resección del tumor de mama primario en los ratones puede restaurar la inmunocompetencia del huésped (Danna 2004). Otro estudio experimental en ratones mostró que después de la resección del tumor primario hubo una reducción en el crecimiento de los tumores metastásicos, lo que indica que la extracción del tumor primario no es solo un fenómeno local (Fisher 1989).

Datos retrospectivos indican que la extracción quirúrgica del tumor primario puede mejorar la supervivencia general en el cáncer de mama metastásico (Blanchard 2008; Fields 2007; Gnerlich 2008; Khan 2002; Rapiti 2006). Lograr márgenes negativos cuando se utiliza la cirugía para tratar el tumor primario parece ser un marcador pronóstico importante para la supervivencia (Khan 2002; Rapiti 2006). Algunos subgrupos de pacientes con enfermedad oligometastásica parecen presentar efectos beneficiosos con la cirugía de mama (Di Lascio 2014; Rastogi 2014). Debido a que las mejorías en el tratamiento sistémico han prolongado la supervivencia de las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico, la cirugía para la enfermedad primaria puede reducir el riesgo de enfermedad local sintomática y posiblemente aumentar la supervivencia. Los efectos beneficiosos potenciales de la cirugía de mama para el cáncer de mama metastásico se debe equilibrar contra las complicaciones perioperatorias y los costos (McNeely 2012).

Por qué es importante realizar esta revisión

Según un metanálisis de estudios retrospectivos, las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico que se sometieron a resección quirúrgica del tumor primario tuvieron una mejor supervivencia general en comparación con las que no se sometieron (Petrelli 2012; Ruiterkamp 2010). En otro metanálisis, las pacientes que se sometieron a cirugía de mama tuvieron una mejor tasa de supervivencia a los tres años que las pacientes que no se sometieron a cirugía (Harris 2013). Sin embargo, todos estos estudios incluidos en los metanálisis fueron retrospectivos y tuvieron las limitaciones típicas de este diseño, incluidos los sesgos de selección y realización. Los cirujanos también tendieron a realizar la resección quirúrgica en las pacientes con enfermedad metastásica que tenían un mejor pronóstico, que generalmente son las pacientes más jóvenes con un buen estado funcional y enfermedad oligometastásica, que de todas maneras habrían sobrevivido más tiempo.

Los ensayos controlados aleatorios (ECA) son el diseño de estudio ideal para reducir las incertidumbres y aclarar si la cirugía es beneficiosa en las pacientes diagnosticadas con cáncer de mama metastásico. Hay varios ensayos en curso que evalúan la cirugía de mama por cáncer de mama metastásico, que incluyen a pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico y asignan al azar a las pacientes a cirugía de mama combinada con tratamiento sistémico o a tratamiento sistémico solo. Se espera que los resultados de algunos de estos ensayos (por ejemplo, NCT00193778 y NCT00557986) estén disponibles en los próximos años. Una revisión sistemática que incluya ECA proporcionaría un resumen integral de la evidencia actual sobre la cirugía de mama en pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico.

Objetivos

Evaluar el efecto de la cirugía de mama en pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico.

Métodos

Criterios de inclusión de estudios para esta revisión

Tipos de estudios

Ensayos controlados con asignación aleatoria (ECA). Se consideraron los estudios informados como texto completo, los publicados como resumen solamente y los datos no publicados.

Tipos de participantes

Pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico al momento del diagnóstico inicial: TNM (tumor, ganglios linfáticos, metástasis) estadio IV (Sobin 2002). Lo anterior incluye cuando el cáncer de mama se ha propagado más allá de la mama, la pared torácica y los ganglios regionales. No se aplicaron restricciones con respecto a la edad ni el tipo histológico. Si un estudio incluyera un subgrupo de participantes elegibles, se incluiría en la revisión siempre que se pudieran extraer los resultados relevantes.

Tipos de intervenciones

-

Grupo de intervención: cirugía de mama del tumor primario, además de tratamiento sistémico (quimioterapia, tratamiento endocrino, inmunoterapia o agentes biológicos).

La cirugía de mama incluyó tumorectomía (resección tumoral con margen de seguridad) o mastectomía (extracción de todo el tejido de la mama). El tratamiento de la axila podría incluir biopsia del ganglio centinela con axila clínicamente negativa y disección axilar (niveles I o II solamente, o niveles I, II y III vaciamiento axilar) con axila clínicamente comprometida o ganglio linfático centinela positivo.

El tratamiento sistémico incluyó quimioterapia, tratamiento endocrino, inmunoterapia o agentes biológicos, así como otros tratamientos novedosos. En ambos brazos se permitió cualquier secuencia de los tratamientos. La cirugía se podría haber realizado antes o después del tratamiento sistémico.

Se aceptó la radioterapia realizada de forma sistemática como parte del tratamiento locorregional del cáncer de mama. La radioterapia se podría haber realizado en la mama o la pared torácica, y en la fosa supraclavicular y la axila ipsilateral, según las guías institucionales. Lo anterior podría haber incluido un refuerzo mediante terapia intersticial de electrones o haz externo y técnicas nuevas. También se permitió la radioterapia para el alivio del dolor o paliativa, en la enfermedad local o a distancia.

-

Grupo de comparación: tratamiento sistémico sin cirugía de mama.

En el grupo control no se realizó cirugía de mama. Se permitió la resección del tumor primario solo para tratamiento paliativo como la hemorragia, la ulceración, la infección, el dolor o la progresión local.

De utilizarse cointervenciones como la quimioterapia, se debían aplicar por igual a cada grupo de estudio.

Tipos de medida de resultado

Se incluyeron los estudios que midieron al menos uno de los resultados enumerados a continuación.

Resultados primarios

-

Supervivencia general, definida como el tiempo transcurrido desde la fecha de asignación al azar hasta la fecha de la muerte (cualquier causa).

-

Calidad de vida, evaluada a través de cuestionarios validados como los de la European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ‐BR23, EORTC QLQ‐BR23, y los cuestionarios BREAST‐Q, BREAST‐Q, u otros descritos en el ensayo clínico.

Resultados secundarios

-

Supervivencia libre de progresión (SLP), definida como el tiempo transcurrido desde la asignación al azar hasta la fecha de la progresión tumoral objetiva o la muerte. La progresión tumoral local y a distancia (control local y control a distancia) se analizó según se muestra a continuación:

-

SLP local, definida como el tiempo transcurrido desde la asignación al azar hasta la recidiva local en el grupo de intervención y como la progresión tumoral local en el grupo control;

-

SLP a distancia, definida como el tiempo transcurrido desde la asignación al azar hasta la progresión fuera del sitio local y los ganglios linfáticos.

-

-

Supervivencia específica del cáncer de mama, definida como el tiempo transcurrido desde la asignación al azar hasta la muerte debido a cáncer de mama. Se suprimieron las pacientes que murieron debido a otras causas diferentes del cáncer de mama.

-

Toxicidad del tratamiento local, incluidas las complicaciones locales y sistémicas.

Se evaluaron los resultados del tiempo transcurrido hasta el evento (supervivencia general, SLP y supervivencia específica del cáncer de mama) al final del período de seguimiento. Se evaluaron los resultados calidad de vida y toxicidad del tratamiento local a corto (hasta seis meses), intermedio (de seis a 24 meses) y a largo plazo (más de 24 meses).

Métodos de búsqueda para la identificación de los estudios

See: Breast Cancer Group for search methods used in reviews.

There were no language restrictions for the studies included in this systematic review. We undertook full translations of all non‐English language papers using local resources.

Búsquedas electrónicas

We searched the following databases on the 22 February 2016:

-

The Cochrane Breast Cancer Group (CBCG) Specialised Register. Details of search strategies used by the CBCG for the identification of studies and the procedures to code references are outlined in the CBCG's module (onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clabout/articles/BREASTCA/frame.html). Trials with the keywords 'advanced breast cancer', 'metastatic breast cancer', 'breast surgery', 'breast‐conserving surgery', 'mastectomy', 'lumpectomy', 'segmentectomy', were extracted and considered for inclusion in the review.

-

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, Issue 1, 2016). See Appendix 1.

-

MEDLINE (via PubMed). See Appendix 2.

-

Embase. See Appendix 3 (via Embase.com for first search) and Appendix 4 (via OvidSP for top‐up search).

-

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) for all prospectively registered and ongoing trials. See Appendix 5.

-

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/). See Appendix 6.

Búsqueda de otros recursos

We also searched for additional studies in the reference lists of identified trials and reviews. We obtained a full copy of each article reporting a potentially eligible trial.

We contacted the authors of the primary studies to seek unpublished data or additional information about the outcomes of interest.

We conducted an additional search in the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) conference proceedings in July 2016.

Obtención y análisis de los datos

Selección de los estudios

Two review authors (GT and BSM) independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant RCTs. We then obtained full‐text articles of all potentially relevant citations. Any disagreements regarding RCT selection were resolved by consulting a third review author (RR). There were no restrictions regarding language or reporting status. We summarised the excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The entire study selection process was reported according to PRISMA guidelines (Moher 2009).

Extracción y manejo de los datos

Two review authors (GT and BSM) independently conducted full data extraction, consulting a third review author (RR) to help resolve any disagreements. We contacted the authors from primary studies to seek unpublished data or additional information about the outcomes of interest (Badwe 2015; Soran 2016). We developed and piloted the data extraction forms, which included the following information from individual studies:

-

publication details;

-

study design, study setting, inclusion/exclusion criteria;

-

participant population (e.g. age, type of surgical procedure, type of tumour);

-

details of intervention;

-

outcome measures;

-

withdrawals, length and method of follow‐up, and the number of participants followed up.

When available, we pooled quantitative data and carried out the analyses using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2012).

In the case of studies with more than one publication, we extracted data from all publications and used them to fill in the same data extraction form, since the unit of analysis was the study rather than the publication. The primary reference was the first publication.

Evaluación del riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos

We assessed risk of bias using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Two review authors (GT and BSM) rated the studies on all seven domains of the 'Risk of bias' tool, consulting a third review author (MRT or RR) to help resolve disagreements. For each domain, we classified the study as having a low, unclear, or high risk of bias. We evaluated the following seven domains:

-

random sequence generation;

-

allocation concealment;

-

blinding of participants and personnel;

-

blinding of outcome assessors;

-

incomplete outcome data;

-

selective reporting;

-

other bias.

We took into account the risk of bias in the Authors' conclusions.

Medidas del efecto del tratamiento

We reported time‐to‐event outcomes such as overall survival, PFS, and breast cancer‐specific survival as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). If necessary, we indirectly estimated HRs using the methods described by Parmar and colleagues (Parmar 1998). We performed intention‐to‐treat analyses.

We intended to report continuous outcomes such as quality of life as mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs. We planned to use standardised mean differences (SMD) if continuous outcomes were reported in different scales.

We reported dichotomous outcomes such as toxicity as risk ratios (RR).

In cases where it was not possible to pool data through meta‐analysis, we presented outcome data narratively.

In an ASCO consensus meeting, the members considered that relevant improvements in median overall survival of at least 20% are necessary to define a clinically meaningful improvement in outcome. They considered HR < 0.8, corresponding to an improvement in median overall survival within a range of 2.5 to 6 months, as the minimum incremental improvement over standard therapy that would define a clinically meaningful outcome (Ellis 2014). We used this definition in the review.

Cuestiones relativas a la unidad de análisis

The unit of analysis was the individual participant, rather than surgical unit, hospital, or centre.

Manejo de los datos faltantes

Where data were missing or unsuitable for analyses (e.g. intention‐to‐treat data were not available), we contacted the study authors to request further information. If data could not be obtained, we did not include the study in the meta‐analysis and discussed these results in the review.

Evaluación de la heterogeneidad

First, we inspected heterogeneity graphically using forest plots displaying effects of individual studies with 95% CIs.

If appropriate, we assessed heterogeneity between studies using the Chi2 statistic (considering a P value < 0.10 as significant). We also used the I2 statistic as an approximate guide to interpret the magnitude of heterogeneity: an I2 value between 30% and 60% was indicative of moderate heterogeneity, while values greater than 50% were considered substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

We investigated the following factors as potential causes of heterogeneity in the included studies, using the framework described below.

-

Clinical heterogeneity: related to study location and setting, full characteristics of participants, comorbidity, and treatments that women may be receiving at trial entry. We considered how outcomes were measured, the definition of outcomes, and how they were recorded.

-

Methodological heterogeneity: related to randomisation process and overall methodological quality of primary studies.

Evaluación de los sesgos de notificación

We planned to create a funnel plot to explore the risk of reporting bias in the case of a meta‐analysis including at least 10 trials. However, none of the meta‐analyses achieved this number of studies. We also planned to perform exploratory analyses to investigate possible reasons for visual asymmetry of funnel plot (chance, publication bias, and true heterogeneity).

Síntesis de los datos

We synthesised data using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2012). To estimate the effect size, we planned to use the MD or SMD for continuous outcomes. We used the HR for time‐to‐event outcomes and RR for dichotomous outcomes. We used the inverse variance method to estimate the combined effect size for the outcomes. We used the random‐effects model by default, as we expected clinical or methodological heterogeneity, or both, among the included studies. Where the data were too diverse for combining effect sizes in a meaningful or valid manner, we presented the results of individual studies in table and graphical format and used a narrative approach to summarise data.

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table (Summary of findings table 1) using the following outcomes: overall survival, quality of life, local PFS, distant PFS, breast cancer‐specific survival, and toxicity from local therapy.

We used the five GRADE criteria (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome stated above. We followed the methods presented in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), employing GRADEpro software (GRADEpro 2014). We explained each judgement to downgrade or upgrade the quality of evidence in the footnotes.

Análisis de subgrupos e investigación de la heterogeneidad

As we expected there to be a small number of published studies, we anticipated that subgroup analyses would not be feasible. Whenever possible, we considered the following subgroup analyses:

-

age > 55 years or < 55 years;

-

oestrogen receptor (ER) status (Lang 2013; Neuman 2010; Perez‐Fidalgo 2011; Petrelli 2012; Samiee 2012);

-

HER2 status (Neuman 2010; Samiee 2012);

-

only bone metastases (Rapiti 2006; Rhu 2015);

-

radiotherapy at primary site or not (Bourgier 2009; Le Scodan 2009).

We based the choice of these planned subgroups on published evidence that the intervention effect could be modified by these characteristics.

Análisis de sensibilidad

We intended to conduct the following sensitivity analyses:

-

by excluding trials at high risk of bias in more than four of the seven domains;

-

by removing studies with eligibility criteria that differed markedly from most of the included studies;

-

by excluding studies in which it was necessary to re‐estimate HRs and CIs using other accepted methodologies;

-

by excluding studies that used any imputation methods for missing data

The sensitivity analysis was not possible due to the small number of studies, but will be considered for future updates of this review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our search strategy identified 4644 records, and two additional trials were identified through manual search. After removing duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 4409 records, excluding 4399 records and selecting 10 for full‐text reading. We excluded two of these 10 records: one was an observational study and one was terminated due to lack of accrual and no further funding (NCT01906112; Ruiterkamp 2012). Four studies were ongoing trials (NCT01015625; NCT01242800; NCT02125630; UMIN000005586). We therefore included four records reporting the results of two RCTs in the review. Both RCTs were included in the quantitative and qualitative syntheses of this review (Badwe 2015; Soran 2016). The flow diagram of the process of study identification and selection is presented in Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The two included studies have the same participants (women with metastatic breast cancer), the same intervention (breast surgery), and the same main outcome (overall survival).

The main difference between the studies was that the Indian study included only women who had responded to systemic therapy (Badwe 2015), while the Turkish study included women with metastatic breast cancer without previous treatment (Soran 2016). Soran 2016 randomised women to upfront breast surgery followed by systemic therapy versus systemic therapy, while Badwe 2015 enrolled women who had responded to first‐line anthracycline‐based chemotherapy and randomised them to breast surgery or continuing medical therapy. By excluding those women who did not respond to chemotherapy, Badwe 2015 excluded the cases of worse prognosis, which did not occur in Soran 2016.

Another important difference between the two studies was the fact that most HER2‐positive women were not treated with anti‐HER2 therapy in Badwe 2015. The fact that only 9 out of 107 women with HER2 overexpression received HER2‐targeted treatment could have influenced the results. Moreover, eight of the nine women who received anti‐HER2 therapy did so only after disease progression (Badwe 2015). In Soran 2016, all women with HER2 overexpression received trastuzumab. The benefits of anti‐HER2 therapy on response rate, PFS, and overall survival are well known since 2001 (Slamon 2001). The combination of trastuzumab and chemotherapy has changed the aggressive natural history of metastatic breast cancer with HER2 overexpression (Dawood 2009).

Another important fact is that the groups were not well balanced in Soran 2016. The group undergoing breast surgery had a larger proportion of women who had tumours that were ER‐positive and HER2‐negative, were younger than 55 years of age, and had single bone metastases compared to the systemic therapy‐alone group. This may have improved the prognosis of the breast surgery group and influenced the results. On the other hand, the two treatment groups in Badwe 2015 were well balanced.

Additional details of the two included RCTs are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Design

Both studies were superiority randomised clinical trials with parallel design (Badwe 2015; Soran 2016).

Sample sizes

To estimate sample sizes, the trial authors considered the following factors.

-

Badwe 2015 considered an improvement in overall survival from 18 to 24 months for breast cancer surgery. Using these premises and considering a P < 0.05 and 80% power, 350 women would be necessary. A total of 716 women were recruited, and 691 women were eligible for systemic chemotherapy. The number of women responding to chemotherapy was 415, and over 25 women were eligible for endocrine therapy. Of the 440 eligible women, 90 were not suitable for surgery or declined to participate. A total of 350 women were randomised: 173 women underwent breast surgery, and 177 women did not.

-

Soran 2016 based the calculations on an expected difference in overall survival between the two groups of 18% (based on previous retrospective studies), a 10% dropout rate including lost to follow‐up, an alfa = 0.05, and a 90% power. This resulted in a total of 271 women. A total of 312 women were recruited, of whom 19 were excluded. Out of 293 eligible women, 19 withdrew or were lost to follow‐up. Of the 274 available women, 138 had breast surgery and systemic treatment, and 136 received systemic treatment alone.

Participants

The two studies evaluated a total of 624 women with metastatic breast cancer. The average age of the women was 49 years. There were 426 women with ER‐positive tumours; 200 women with ER‐negative tumours; 192 women with HER2‐positive tumours; 421 with HER2‐negative tumours; and 226 women with bone‐only metastases.

Badwe 2015 included women with metastatic breast cancer with objective response to first‐line chemotherapy (> or = 50% clinical response). Women were stratified by site of metastases (visceral only, bone only, or visceral plus bone), number of metastases (≤ 3 or > 3), and hormone receptor expression sensitivity (ER‐ or progesterone receptor (PR)‐positive or ER‐ and PR‐negative), and then randomised to receive breast surgery plus further systemic treatment or systemic treatment alone.

Soran 2016 enrolled treatment‐naïve women with resectable primary tumour and randomly assigned women to upfront surgery followed by systemic therapy or systemic therapy alone.

Interventions

Surgery

The intervention was the surgical resection of the tumour with safety margins through mastectomy or conservative surgery. The assessment of axillary involvement was performed at the same time as the breast surgery. Soran 2016 performed sentinel lymph node biopsy in women without clinical disease in the lymph nodes and performed lymphadenectomy in women with proven (previous axillary biopsy or positive sentinel node) or clinically affected armpit. In Badwe 2015, all women underwent axillary lymph node dissection and additional supraclavicular lymph node dissection for suspected disease.

Radiotherapy

Postoperative radiotherapy was performed in all women who underwent breast‐conserving surgery in both studies. In Badwe 2015, postoperative radiation was given to women who underwent mastectomy with pre‐chemotherapy tumours over 5 cm or skin or chest wall involvement or axillary lymph node‐positive disease. Conventional external beam radiotherapy was delivered to the chest wall with or without the supraclavicular fossa at a dose of 45 Gy, 20 fractions over 4 weeks. Women undergoing breast‐conserving surgery received whole‐breast radiotherapy in one of two ways: 45 Gy, 25 fractions over 5 weeks with a tumour bed boost of 15 Gy, 6 fractions over 1 week; or 50 Gy, 25 fractions over 5 weeks with a tumour bed boost of 15 Gy, 6 fractions over 1 week in locally advanced cancers (Badwe 2015). In Soran 2016, radiotherapy was given to women undergoing mastectomy depending on the extent of the disease and following each institutional guideline. Radiation therapy fields, dosing, and schedule were not described (Soran 2016).

Chemotherapy and targeted therapy

Most women in both studies received anthracycline‐based chemotherapy.

In Badwe 2015, women underwent chemotherapy before randomisation, and only those who had clinical response greater than or equal to 50% were included. Chemotherapy comprised six cycles of anthracycline‐based or eight cycles of a sequential anthracycline‐taxane regimen or six cycles of concurrent anthracycline‐taxane chemotherapy. About 95% of women received anthracycline‐based combination chemotherapy. Anti‐HER2 treatment was available to a small number of women; just 9 of 107 with HER2‐positive tumours received HER2 target treatment (Badwe 2015).

In Soran 2016, all women received upfront surgery followed by chemotherapy or upfront chemotherapy. Approximately 80% of women received anthracycline‐based chemotherapy. Trastuzumab was available to all HER2‐positive women (Soran 2016).

Endocrine therapy

Endocrine therapy was available to all ER‐positive breast cancer patients in both studies. In Badwe 2015, women with ER‐ or PR‐positive tumours received standard endocrine therapy after locoregional treatment. The treatment consisted of tamoxifen 20 mg per day for premenopausal women and an aromatase inhibitor (2.5 mg letrozole per day or 1 mg anastrozole per day) or tamoxifen for postmenopausal women, until disease progression. In the intervention group, premenopausal women with ER‐ or PR‐positive tumours who continued to have menstrual cycles after chemotherapy, had bilateral oophorectomy at the time of the surgical removal of their primary tumour. In the group without breast surgery, women with ER‐ or PR‐positive tumours who continued to have menstrual cycles after chemotherapy also underwent bilateral oophorectomy followed by hormone therapy treatment as previously described (Badwe 2015). Soran 2016 did not specify which endocrine therapy was used.

Follow‐up

The median follow up was 23 months in Badwe 2015 and 40 months in Soran 2016. The number of deaths precluded mature data for overall survival.

Excluded studies

We excluded two studies; the reasons for exclusion are presented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

We used Cochrane’s tool for assessing risk of bias as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). See the 'Risk of bias' summary in Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Selection bias

The two studies were described as randomised clinical trials. Badwe 2015 used a computerised stratified randomisation, and allocation concealment was ensured by a central office. These procedures minimised the risk of selection bias in this study. Soran 2016 described verbatim "a phase III randomised controlled trial". Despite several attempts to contact the authors, we were unable to obtain further explanation. We judged Soran 2016 as having an unclear risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Performance and detection bias

Blinding was not feasible in either study due to the surgical procedure planned in the interventional arm. The lack of blinding of the outcome assessor may have influenced the results for subjective outcomes (high risk of bias) but not for overall survival (low risk of bias).

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition bias

In both studies, there was no information about missing/censored data, and we classified them as having an unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Selective reporting

Reporting bias

The study protocols were available for both studies, and the primary outcomes were fully reported. The secondary outcomes have not been reported so far, but we did not consider this as a potential source of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

There was an imbalance between groups in Soran 2016. In the group undergoing breast surgery, there was a higher proportion of women who were younger than 55 years, had ER‐positive and HER2‐negative tumours, and had single bone metastases. It is likely that these differences between the two groups could have influenced the result. We therefore considered Soran 2016 as having a high risk of bias for this domain.

Effects of interventions

Overall survival

As the quality of evidence was judged as very low, it is uncertain whether breast surgery plus systemic treatment improves overall survival compared to the systemic treatment alone (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.31; 2 studies; 624 women; I2 = 82%; very low‐quality evidence, downgraded due to study limitations, inconsistency, and imprecision) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 3). The estimated number of deaths was 448 per 1000 participants (ranging from 318 to 608 deaths per 1000 participants) in the breast surgery plus systemic treatment group and 511 per 1000 participants in the systemic treatment‐alone group (summary of findings Table for the main comparison).

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, outcome: 1.1 Overall survival.

Overall survival subgroup analysis

Refer to 'Overall survival ‐ subgroup analyses' (Table 1).

| Overall survival subgroup analysis | Number of studies | N | HR | Lower CI | Upper CI | P value |

| HER2‐positive | 2 | 192 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 1.35 | NS |

| HER2‐negative | 2 | 421 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 1.08 | NS |

| ER positive | 2 | 426 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 1.03 | NS |

| ER negative | 2 | 200 | 1.01 | 0.73 | 1.40 | NS |

| Bone‐only metastasis | 2 | 226 | 0.91 | 0.49 | 1.69 | NS |

CI: confidence interval

ER: oestrogen receptor

HR: hazard ratio

NS: not significant

HER2 status

For both HER2‐positive and ‐negative subgroups, the results were consistent with the main analysis:

-

HER2‐positive: HR 0.85 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.50; 2 studies; 192 women; I2 = 39%; Analysis 1.2);

-

HER2‐negative: HR 0.84 (95% CI 0.50 to 1.40; 2 studies; 421 women; I2 = 79%; Analysis 1.2).

There was no evidence of a difference in overall survival between HER2‐positive and HER2‐negative subgroups (Chi2 = 0.00, df = 1 (P = 0.97), I2 = 0%).

Oestrogen receptor status

For both ER‐positive and ‐negative subgroups, the results were consistent with the main analysis:

-

ER‐positive: HR 0.83 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.42; 2 studies; 426 women; I2 = 74%; Analysis 1.3);

-

ER‐negative: HR 1.04 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.55; 2 studies; 200 women; I2 = 19%; Analysis 1.3).

There was no evidence of a difference in overall survival between ER‐positive and ER‐negative subgroups (Chi2 = 0.44, df = 1 (P = 0.51), I2 = 0%).

Only bone metastasis

For the subgroup of women with bone metastasis, there was no difference between the interventions: HR 0.91 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.69; 2 studies; 226 women; I2 = 70%; Analysis 1.4).

Radiotherapy or no radiotherapy at the primary site

Not measured in included studies.

Quality of life

The included studies did not report this outcome. Quality of life was described as an outcome in the protocols of both studies; we expect these results to be published soon.

Progression‐free survival

Local PFS

The two included studies evaluated local PFS involving 607 women, and breast surgery plus systemic treatment may improve local PFS when compared to systemic treatment alone (HR 0.22, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.57; 2 studies; 607 women; I2 = 43%; low‐quality evidence) (Analysis 1.5;Figure 4). The estimated number of events was 141 per 1000 participants (ranging from 54 to 326 events per 1000 participants) in the breast surgery plus systemic treatment group and 500 in 1000 participants in the systemic treatment‐only group. We downgraded the quality of the evidence due to study limitations and inconsistency. When considering the width of the confidence interval, the result is clinically relevant.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, outcome: 1.5 Progression‐free survival.

Distant PFS

Only Badwe 2015 analysed distant PFS. The group receiving breast surgery plus systemic treatment probably had a shorter time to distant PFS compared to the group receiving systemic treatment alone (HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.86; 1 study; 350 women; moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.5; Figure 4). The estimated number of events was 676 per 1000 participants (ranging from 576 to 772 events per 1000 participants) in the breast surgery plus systemic treatment group and 548 in 1000 participants in the systemic treatment‐only group. We downgraded the quality of the evidence due to study limitation (lack of blinding of outcome assessors).

Breast cancer‐specific survival

The included studies did not measure this outcome.

Toxicity from local therapy

Soran 2016 reported that toxicity (assessed by 30‐day mortality) did not appear to differ between the breast surgery plus systemic treatment group and systemic treatment‐only group (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.14 to 6.90; 1 study; 274 women; low‐quality evidence). We downgraded the quality of the evidence due to study limitation (lack of blinding of outcome assessors).

Discusión

Resumen de los resultados principales

No hay seguridad con respecto a si la cirugía de mama mejora la supervivencia general en las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico debido a que la evidencia es de muy baja calidad. La cirugía puede mejorar la SLP local (evidencia de baja calidad) y empeorar la SLP a distancia (evidencia de calidad moderada). No se encontraron datos para la supervivencia específica del cáncer de mama. La toxicidad del tratamiento local (medida por la mortalidad a los 30 días) parece ser similar en ambos grupos (evidencia de baja calidad), según un estudio.

Las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico son un grupo heterogéneo de pacientes con diferentes pronósticos. Las pacientes con enfermedad metastásica mínima tienen mejor supervivencia que las pacientes con órganos múltiples afectados por las metástasis (Badwe 2015). Badwe 2015 incluyó mujeres sintomáticas probablemente con diagnóstico tardío en el curso natural de la enfermedad metastásica de novo. Aunque el 74% de las pacientes incluidas en el estudio indio tenían más de tres sitios metastásicos (Badwe 2015), en el estudio turco este porcentaje fue del 40% (Soran 2016). Los estudios realizados en países como Estados Unidos, así como en Europa, pueden incluir a pacientes con enfermedad metastásica en un estadio más temprano y el efecto de la cirugía de mama en estas mujeres puede ser diferente.

El tratamiento sistémico es efectivo en el control de la enfermedad de la mama y metastásica con repercusión sobre la supervivencia general (Kiess 2012; Slamon 2001). La gran mayoría de las pacientes de ambos estudios recibieron quimioterapia con antraciclina: 80% en Soran 2016 y 95% en Badwe 2015. Sólo el 5% de las pacientes de Badwe 2015 recibieron antraciclina más taxano. En el estudio turco (Soran 2016), todas las pacientes con tumor con sobreexpresión de HER2 recibieron trastuzumab, mientras que solamente el 8,5% recibió tratamiento anti‐HER2 en el estudio indio (Badwe 2015); por lo tanto, 98 mujeres (15%) incluidas en el metanálisis no recibieron tratamiento sistémico adecuado. El estudio Clinical Evaluation of Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab (CLEOPATRA) mostró una ganancia en la supervivencia con la administración de bloqueo doble (trastuzumab más pertuzumab) en comparación con la administración de solo un anticuerpo monoclonal, como tratamiento de primera línea (Swain 2015). Por lo tanto, la no utilización del tratamiento anti‐HER2 redujo la supervivencia general en estas mujeres y también disminuyó las probabilidades de un posible efecto beneficioso de la cirugía de mama.

No se esperaba que el tratamiento local proporcionara un efecto beneficioso de gran tamaño sobre la supervivencia de las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico. Se hizo un paralelismo con el efecto de agregar radioterapia al tratamiento con cirugía de mama conservadora. Las primeras publicaciones ya informaron que la radioterapia mostró un efecto beneficioso en el control de la enfermedad local, pero la intervención mostró un efecto beneficioso en la supervivencia solo después de un metanálisis reciente con un gran número de participantes y un seguimiento más prolongado (Darby 2011).

La cirugía de mama mostró ser efectiva en el control de la enfermedad local y redujo a la mitad el número de muertes debido a enfermedad local no controlada (el 6% murió de enfermedad localmente no controlada en el grupo sin tratamiento locorregional versus el 3% en el grupo con tratamiento locorregional) (Badwe 2015). La tasa de cirugía de mama de rescate para el tratamiento de la progresión local en el grupo control fue del 10,2% (18 de 177) en 2015 Badwe y del 3,6% (5 de 138) en Soran 2016. Es importante recalcar la baja toxicidad del tratamiento local y el punto de vista de las pacientes de que la cirugía reduce el riesgo de necesitar una intervención tardía en el curso de la enfermedad. La SLP a distancia fue peor en las pacientes sometidas a cirugía de mama. El tiempo que estas pacientes permanecieron sin tratamiento sistémico debido a la cirugía puede haber contribuido a este resultado.

La calidad general de la evidencia es baja debido a las limitaciones de los estudios, la inconsistencia y la imprecisión. Es probable que los estudios de investigación adicionales puedan tener una marcada repercusión sobre la estimación del efecto y probablemente cambien la estimación.

Compleción y aplicabilidad general de las pruebas

Las pacientes incluidas en el estudio indio presentaban un estadio avanzado de la enfermedad y en su mayoría estaban sintomáticas (Badwe 2015). Este perfil de pacientes se encuentra con mayor frecuencia en los países donde el sistema de salud y los programas de cribado no son efectivos. Se cree que los estudios en países de ingresos altos pueden incluir pacientes con estadios menos avanzados de la enfermedad, lo que podría influir en los efectos de la intervención.

Se espera incluir datos sobre la calidad de vida en las actualizaciones futuras de esta revisión. Este resultado es muy importante para la toma de decisiones.

Calidad de la evidencia

Como se presenta en la Tabla 1 Resumen de los hallazgos, la calidad del grupo de evidencia para cada resultado fue moderada a muy baja.

Las razones principales para la disminución de la calidad de la evidencia fueron la heterogeneidad alta entre los estudios (inconsistencia), IC amplios (imprecisión) y el riesgo de sesgo de selección de un estudio (riesgo de sesgo).

Para el resultado supervivencia general, la calidad se disminuyó a muy baja debido a: (a) generación de la secuencia de asignación al azar y ocultación de la asignación poco claras Soran 2016; (b) heterogeneidad clínica y estadística altas entre los estudios (I2 = 82%); y (c) intervalos de confianza muy amplios (IC del 95%: 0,53 a 1,31) (GRADEpro 2014).

Para el resultado SLP local la calidad de la evidencia se disminuyó a baja debido a: (a) generación de la secuencia de asignación al azar y ocultación de la asignación poco claras Soran 2016; y (b) heterogeneidad clínica y estadística altas entre los estudios (I2 = 42%) (GRADEpro 2014).

Para el resultado SLP a distancia la calidad de la evidencia se disminuyó a moderada debido a las limitaciones de los estudios (los evaluadores de resultado no se cegaron y este es un resultado subjetivo) (GRADEpro 2014).

Para el resultado toxicidad del tratamiento local la calidad de la evidencia se disminuyó a baja debido a: (a) generación de la secuencia de asignación al azar y ocultación de la asignación poco claras Soran 2016; y (b) intervalos de confianza amplios (IC del 95%: 0,14 a 6,9) (GRADEpro 2014).

Por lo tanto, es probable que los estudios de investigación adicionales con períodos de seguimiento más prolongados tengan repercusión sobre las estimaciones del efecto.

Debido a que hay cuatro estudios en curso, es posible que algunas de estas limitaciones se puedan reducir al mínimo en la actualización de esta revisión.

Sesgos potenciales en el proceso de revisión

Para disminuir el riesgo de sesgo se siguieron estrictamente las recomendaciones del Manual Cochrane para revisiones sistemáticas de intervenciones para la búsqueda, la selección de los estudios, la obtención de los datos y el análisis de los datos (Higgins 2011). Una de las fortalezas de esta revisión es la búsqueda bibliográfica amplia y actualizada.

La limitaciones de esta revisión incluyen: (a) no se realizó una evaluación del sesgo de publicación a través del análisis de los gráficos en embudo (funnel plot) porque en el metanálisis se incluyeron menos de diez estudios; (b) algunos análisis de subgrupos no se planificaron en la fase de protocolo; y (c) las limitaciones típicas del metanálisis de los datos agrupados, cuando faltan los datos de pacientes individuales y el análisis de subgrupos generalmente tiene escaso poder estadístico.

Acuerdos y desacuerdos con otros estudios o revisiones

Aunque anualmente a miles de mujeres se les diagnostica cáncer de mama metastásico, hasta donde se conoce esta es la primera revisión sistemática con metanálisis de ensayos aleatorios sobre los efectos de la cirugía local en estos casos.Hay algunas revisiones sistemáticas de estudios observacionales que muestran un efecto beneficioso general en la supervivencia de las pacientes con cáncer de mama metastásico que se someten a cirugía de mama. Estos estudios tienen las limitaciones inherentes a los diseños observacionales y no son el tipo más apropiado de estudios para evaluar la efectividad de una intervención. Esta revisión sistemática no coincide con los estudios retrospectivos que muestran un efecto beneficioso en la supervivencia en pacientes sometidas a cirugía de mama (Blanchard 2008; Fields 2007; Gnerlich 2008; Khan 2002; Rapiti 2006).

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, outcome: 1.1 Overall survival.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, outcome: 1.5 Progression‐free survival.

Comparison 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

Comparison 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, Outcome 2 Overall survival ‐ HER2 status.

Comparison 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, Outcome 3 Overall survival ‐ ER status.

Comparison 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, Outcome 4 Overall survival ‐ only bone metastasis.

Comparison 1 Systemic treatment plus surgery versus systemic treatment, Outcome 5 Progression‐free survival.

| Breast surgery plus systemic treatment compared to systemic treatment for metastatic breast cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: metastatic breast cancer | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with systemic treatment | Risk with breast surgery plus systemic treatment | |||||

| Overall survival at 2 years Follow‐up: range 23 months to 40 months | Study population | HR 0.83 | 624 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | The estimates for the control group are based upon an average of the estimates from Badwe 2015 and Soran 2016. | |

| 511 per 1000 | 448 per 1000 | |||||

| Quality of life | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Local PFS at 2 years Follow‐up: range 23 months to 40 months | Study population | HR 0.22 | 607 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The estimates for the control group are based upon an average of the estimates from Badwe 2015 and Soran 2016. | |

| 500 per 1000 | 141 per 1000 | |||||

| Distant PFS at 2 years Follow‐up: 23 months | Study population | HR 1.42 | 350 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | The estimates for the control group are based upon the estimates from Badwe 2015. | |

| 548 per 1000 | 676 per 1000 | |||||

| Breast cancer‐specific survival | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Toxicity from local therapy Follow‐up: 40 months | Study population | RR 0.99 | 274 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | The estimates for the control group are based upon the estimates from Soran 2016. | |

| 15 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1In Soran 2016, trial random sequence generation and allocation concealment were unclear. Downgraded one level. | ||||||

| Overall survival subgroup analysis | Number of studies | N | HR | Lower CI | Upper CI | P value |

| HER2‐positive | 2 | 192 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 1.35 | NS |

| HER2‐negative | 2 | 421 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 1.08 | NS |

| ER positive | 2 | 426 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 1.03 | NS |

| ER negative | 2 | 200 | 1.01 | 0.73 | 1.40 | NS |

| Bone‐only metastasis | 2 | 226 | 0.91 | 0.49 | 1.69 | NS |

| CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Overall survival Show forest plot | 2 | 624 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.53, 1.31] |

| 2 Overall survival ‐ HER2 status Show forest plot | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 HER2‐positive | 2 | 192 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.48, 1.50] |

| 2.2 HER2‐negative | 2 | 421 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.50, 1.40] |

| 3 Overall survival ‐ ER status Show forest plot | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 ER‐positive | 2 | 426 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.48, 1.42] |

| 3.2 ER‐negative | 2 | 200 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.70, 1.55] |

| 4 Overall survival ‐ only bone metastasis Show forest plot | 2 | 226 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.49, 1.69] |

| 5 Progression‐free survival Show forest plot | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Local progression‐free survival | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.08, 0.57] | |

| 5.2 Distant progression‐free survival | 1 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 1.42 [1.08, 1.86] | |