Aromaterapija za liječenje postoperativne mučnine i povraćanja

Referencias

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

References to ongoing studies

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT of peppermint oil, IPA or normal saline aromatherapy to treat PONV Setting: PACU acute hospital, USA | |

| Participants | 33 patients aged 18 years + having surgery under general or regional anaesthesia, or deep IV sedation, who reported nausea in PACU. Treatment groups did not differ in the percentage having general anaesthesia, the type of surgery, age or gender distribution. Exclusions: patients who were unable to give informed consent; patients who did not require anaesthesia services | |

| Interventions | On the participant's spontaneous report of PON, they were instructed to take three slow deep breaths to inhale the vapours from a pre‐prepared gauze pad soaked with either peppermint oil (n = 10), IPA (n = 11), or normal saline placebo (n = 12) held directly under their nostrils. After 2 min the participant was asked to rate their nausea by VAS and given the choice to continue aromatherapy or have standard IV antiemetics. At 5 min post the initial treatment, the participant was again asked to rate their nausea and if they would like to continue aromatherapy or have standard IV antiemetics. | |

| Outcomes |

| |

| Notes | Possible lack of accuracy with some participants self‐recording data in PACU if they had poor or blurred vision. Authors Lynn Anderson and Dr Jeffrey Gross emailed to request further information on group sizes, which was supplied by Dr Gross. Supported by the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Connecticut School of Medicine. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "...group assignments were made in a randomised, double‐blind fashion" Comment: probably done. Nurses administering treatment were unaware of contents of each package of treatment materials. Patients who had consented to participate entered study when they spontaneously reported nausea. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "A random number generator determined the contents of each serially numbered bag." "...prepared by an individual not otherwise involved in the study..." Data "analysed by investigator unaware of treatment allocation". Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Staff administering treatment blinded by use of "lightly scented" surgical masks. Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Participants were self‐reporting subjective assessment of nausea and were not blinded. Comment: due to the strong aroma of the peppermint oil, it would be impossible to blind the participant receiving this to their allocation once treatment commenced. Probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: outcomes reported for all participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: results reported for all stated outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

| Methods | Prospective randomized study of IPA inhalation as compared to IV ondansetron for PONV. Replication of study: Winston 2003. Setting: PACU/same day surgery unit, USA | |

| Participants | 21 women aged 18‐65 who were scheduled for laparoscopic same‐day surgery (ASA physical status I, II or III), n = 10 treatment, n = 11 control Exclusions: patients who had recent upper respiratory tract infections, inability or impaired ability to breathe through the nose, or history of hypersensitivity to IPA, 5‐HT3 receptor antagonists, promethazine or any other anaesthesia protocol medication, had used an antiemetic within 24 hours of surgery, were pregnant or breastfeeding, had history of inner ear pathology, motion sickness or migraine headaches or were taking disulfiram, cefoperazone, or metronidazole | |

| Interventions | Comparison of inhaled IPA to intravenous ondansetron for treatment of PONV Ondansetron (control) group: nausea treated with ondansetron 4 mg IV every 15 min to a maximum 8 mg dose. Time, dose and VNRS score recorded IPA (experimental) group: nausea treated by holding a folded alcohol pad approximately 1/2 inch (approximately 1.3 cm) from the participant's nares and instructing them to take 3 deep breaths in and out through the nose. Treatments given every 5 min up to a total of 3 administrations Breakthrough PONV was treated with promethazine suppositories for both groups. Participants were also given supplies of IPA and promethazine to use as needed at home after discharge and asked to record any occurrences of PONV with a data collection tool provided by the researchers. | |

| Outcomes | Time to reduction in nausea score as measured by VRNS (range 0‐10 where 0 = no nausea and 10 = worst imaginable nausea). Collected for baseline at pre op, then immediately postop in PACU and at any time the participant complained of nausea. Additionally, participants who complained of nausea were assessed every 5 min following treatment for 30 min and then every 15 min until discharge from PACU. Participants also reported data on PONV for the 24 h post‐discharge as well rating their anaesthesia experience overall. | |

| Notes | Author, Joseph Pellegrini contacted for further data. Some was provided however due to data corruption problems not all requested data were available. Support was received from the US Navy Clinical, Investigation Department. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "patient was randomly assigned to the control group or the experimental group by using a computer‐generated random numbers program." Comment: done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Block randomisation was used for all of the studies using a computer generated randomisation program done by an independent party (myself) who was not involved in the data collection" (emailed author response) Comment: done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information given regarding blinding. Does not appear to have been done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information given regarding blinding. Does not appear to have been done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | 28 participants "disenrolled due to protocol violations": 12 from control group who were given IPA postoperatively; 6 from experimental group given other antiemetics in PACU before IPA; and 10 who lost their IPA or promethazine following discharge to home. Comment: probably done |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: results reported for all stated outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

| Methods | 2‐group CCT comparing controlled breathing to controlled breathing with IPA aromatherapy. Experimental group (n = 41) received controlled breathing exercise (3 deep breaths in and out, guided by PACU nurse) and an IPA pad held under their nose at the same time. Control group (n = 41) received controlled breathing exercise only Setting: day surgery unit, USA | |

| Participants | 82 women having laparoscopic surgery. Age range: 18‐59 years, (mean = 40.5 (SD = 11.35)) No significant differences between experimental and control in history of PONV, or type of procedure. No significant difference in time spent in surgery and recovery, or total amount of fluids received. Mean ages significantly different between groups: experimental group (mean = 43.2) versus control (mean = 37.8). Also there were significantly fewer smokers in the experimental group (5%) than the control group (20%). | |

| Interventions | Controlled breathing with and without IPA aromatherapy. IPA aromatherapy: standard 'prep‐pad' held under participant's nose while breathing deeply | |

| Outcomes | Nausea severity as measured on a VNRS (0‐10, 0 = no nausea, 10 = worst possible) at initial complaint, 2 min and 5 min, use of rescue medications | |

| Notes | Conference abstract: further information received from study authors. No information on funding sources | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "This study used a prospective randomized two‐group experimental design." "Randomization was based on the calendar month, with the experimental treatment group assigned in even months and the control group assigned during odd months." Comment: study is CCT |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | "...experimental treatment group assigned in even months and the control group assigned during odd months." Comment: probably not concealed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | "For those in the experimental group, in addition to the CB coaching, an IPA pad was placed directly under the nostrils of the patient, so that aromatherapy was received during inhalation." Comment: likely no blinding of participants or staff administering intervention |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: the publication does not state who measured the treatment outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | "...RNs verbalized that the actual PON score was difficult to obtain when a patient was severely nauseated. We excluded these patients which decreased our sample size to 82." Comment: exclusion of severely nauseated participants a potential source of bias, but it is unclear from reported results to which group these participants were allocated |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: stated outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: no other sources of bias apparent |

| Methods | 3‐group non‐RCT comparing peppermint vapour, saline vapour and ondansetron to treat PON | |

| Participants | 70 non‐pregnant female surgical patients (23 peppermint/22 saline/25 ondansetron) > 18 years undergoing a surgical procedure at a suburban community hospital. Exclusionary criteria were olfactory sensory loss, allergy to peppermint, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic respiratory conditions Setting: community hospital, USA | |

| Interventions | Peppermint oil or normal saline placed on identical size gauze squares and sealed in zip‐lock plastic bags. Treatment administered on initial complaint of nausea in PACU. Aromatherapy group participants instructed to take one inhalation from opened bag. Ondansetron group received 4 mg IV. A VAS was used to rate nausea at the first complaint; at 5 min after intervention; and, if nausea persisted, at 10 min after intervention | |

| Outcomes | Nausea severity at 3 and 5 min (and, if nausea persisted, at 10 min after intervention) as measured by 200 mm VAS (0 = no nausea, 200 = worst possible nausea) | |

| Notes | Confirmation received from study authors that while a 200 mm VAS was used to measure nausea, the results were converted to centimetres (i.e. 20 cm scale, 0‐20) in the published report. No information on funding sources | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "For those receiving inhalation, the investigators randomly selected a sealed zip lock bag from a box containing bags of both peppermint and saline aromas." Comment: not done: study is CCT |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: not done: study is CCT |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: probably not done: no statement addressing blinding, although peppermint and saline treatments appeared identical & stored in same box, investigators would have been unblinded to treatment when bag opened due to odour |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no blinding of assessors described. Study investigators appear to have assessed outcomes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: no attrition described. Results of all participants reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: all outcomes stated in the paper also have data reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: no other sources of bias apparent |

| Methods | 2‐group RCT comparing commercial aromatherapy preparation to placebo | |

| Participants | 94 adult surgical patients (54 treatment/40 control) patients with planned admission. Patients with an allergy to lavender, peppermint, spearmint, or ginger excluded. Mean Age = 41.25 years. SD = 14.2. Range= 18‐86 Setting: military medical centre, USA | |

| Interventions | Treatment: patient‐administered inhalations from 'QueaseEase™' commercial aromatherapy inhaler containing peppermint, spearmint, lavender and ginger oils. Control: unscented placebo inhaler. On first complaint of nausea, "the patient is instructed to remove the cap, hold the container under the nose, and take a few deep breaths." | |

| Outcomes | Nausea severity at initial report and 3 min as measured on a 10‐point Likert scale (0 = no nausea, 10 = worst possible nausea). Patient satisfaction as measured by a questionnaire. | |

| Notes | 27 patients eligible for the study did not receive the allocated treatment. Additional information requested & supplied. QueaseEase™ devices and placebo devices were provided free of charge by the manufacturer. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Probably done: further information received from study author, Nancy Hodge, states that a computer‐generated random number sequence was used. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Comment: probably not done. No concealment described in published paper or extra information provided by study author |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Probably done: further information from study author, Nancy Hodge, states: "The perceived nausea VAS forms and interview questions forms were placed in a sealed packet along with either an aromatherapy inhaler or a placebo inhaler. Each packet was numbered and randomly assigned an inhaler. The sealed packets were placed on the nursing unit and when a post‐op patient complained of nausea the nurse took the next numbered packet to the bedside." Comment: despite these measures, unblinding of participants would have occurred on opening the packets due to the scent of the aromatherapy product |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Comment: despite the above measures, unblinding of nursing staff would have occurred on opening the packets due to the scent of the aromatherapy product. The nursing staff who administered the intervention also measured the outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: the 27 patients whose outcomes were not included did not receive any of the study treatments |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: no evidence of selective reporting. All stated outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other sources of bias apparent |

| Methods | 4‐group RCT comparing an aromatherapy blend (n = 74), ginger aromatherapy (n = 76), and IPA (n = 78), with a saline placebo (n = 73) | |

| Participants | 301 adult patients having surgical procedures. Inclusion criteria: "age 18 years or older, being cognitively able to give informed consent, having surgery that day, not receiving warfarin (Coumadin), heparin, full dose 325 mg aspirin, or clopidogrel (Plavix), and not having a history or diagnosis of bleeding diatheses or any known allergies to ginger, spearmint, peppermint, or cardamom. The exclusion of patients with clotting disorders was based on studies finding antiplatelet and cyclooxygenase‐ 1 enzymes inhibitors from constitutions of ginger." Setting: ambulatory surgical centre, USA | |

| Interventions | Comparison of normal saline, 70% IPA, essential oil of ginger, and a blend of the essential oils of ginger, spearmint, peppermint, and cardamom. "Each aromatherapy was stored in a plain white bottle labelled 1 to 4 and kept in a locked cart labelled “For Research Purposes Only.” "One millilitre of the randomly selected, designated aromatherapy was placed on a 2‐inch by 2‐inch [5 cm x 5 cm] impermeable, backed gauze pad. On complaint of nausea, participants were instructed to inhale the scent through the nose 3 times." | |

| Outcomes | Nausea severity at first complaint and 5 min as measured on a 4‐point Likert scale (0 = no nausea, 3 = severe) reported as percentage improvement in nausea scores, percentage requiring rescue antiemetics | |

| Notes | Additional information requested and promised but not yet supplied. No funding received | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Participants who responded with a [nausea] score of 1 to 3 were randomly assigned to 1 of the 4 treatment groups using a computerized listing for random assignments generated by Assumption College." Comment: likely done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | "The research nurse checked off the study number of the participant and aromatherapy on the list and then prepared the gauze pad." Comment: probably not done. Allocator reported as preparing the intervention treatments |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | "Despite the lack of any identifying label, the study treatment arms could not be blinded because of the specificity of odours." Comment: probably not done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | "Despite the lack of any identifying label, the study treatment arms could not be blinded because of the specificity of odours." Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | "...2 subjects were excluded from the protocol analysis because of what was believed to be a degradation of the blend of the aromatherapy Comment: low attrition |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: small range of outcomes, all reported. No protocol available |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other sources of bias apparent |

| Methods | RCT of IPA versus normal saline placebo for treatment of PONV Setting: postoperative care unit, acute hospital, Iran | |

| Participants | 82 consecutive patients randomized into experimental (n = 41) and control (n = 41) groups. No age data or demographic except 48 female/34 male | |

| Interventions | 2 sniffs of IPA (treatment) or 2 sniffs normal saline (control) (on reporting symptoms) and re‐treated at 5 min if necessary. Participants who did not respond the 2nd time received metoclopramide injection. | |

| Outcomes | Response to treatment/cessation of symptoms, recurrence of symptoms, use of rescue antiemetics | |

| Notes | Attempted to contact study author, Dr H Kamalipour, via email however no response received | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "The patients were randomly divided into two groups." Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no data |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no data |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no data |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: data reported for all stated outcomes |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: brief report with little detail |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: unable to ascertain from details reported |

| Methods | 2‐group RCT comparing 'Quease Ease' aromatherapy blend to saline placebo | |

| Participants | 39 children aged 4‐16 years (21 intervention/18 control) admitted for elective day surgery. Anesthesia Society of America Physical Status I or II (ASA I or II) Exclusion criteria included the presence of neurodevelopmental disorders, allergy or sensitivity to aromatherapy components, or inability to smell Setting: health centre in Canada | |

| Interventions | Intervention participants received QueaseEase™ commercial aromatherapy blend (lavender, spearmint, ginger and peppermint) contained in a plastic inhaler delivery system on first report of nausea in PACU. Control participants received saline placebo in identical plastic inhaler delivery system on first report of nausea in PACU. | |

| Outcomes | Nausea incidence and severity as measured by the 11‐point Baxter Retching Faces (BARF) scale (0 = no nausea, 10 = vomiting) every 15 min until discharge. | |

| Notes | Funding of this study was from the Dr Thomas Coonan Studentship through the Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "If the patient reported a BARF scale of 4 or greater they were randomized to the intervention aromatherapy or a saline inhaler. Randomization was by block 6 design." Comment: unclear how sequence was generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Concealment was maintained by using sequentially numbered opaque envelopes containing the identical appearing intervention and control inhalers." Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Intervention and control devices were identical in appearance. "The control was with identical housing but contained only saline." "Despite a delivery system with controlled exposure to the therapy (twist top) the aroma rapidly penetrated the area around the patient. Researchers and nurses correctly identified intervention versus control in all cases." Comment: likely that unblinding to allocation occurred due to the odour of the intervention device |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | "Despite a delivery system with controlled exposure to the therapy (twist top) the aroma rapidly penetrated the area around the patient. Researchers and nurses correctly identified intervention versus control in all cases." Comment: likely that unblinding to allocation occurred due to the odour of the intervention device |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | "Randomization occurred in 41 subjects of which 2 were excluded post randomization (1 subject in each arm [1], for failure to meet exposure criteria and [1] for leaving before assessment." Comment: no concerns |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Primary and secondary outcomes planned in study registration are reported in study |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | "The aromatherapy sticks and saline control were provided in kind by QueaseEASE™. " Comment: the study authors state the company was not involved in study methodology. "Unreliability of the outcome measurement (BARF scale) in the youngest children may also contribute to error. Although the BARF scale has been validated down to 4 years old, there is variability in children’s ability to self‐report on internal experiences in this age group that may have influenced Comment: some risk of outcome measurement error "Despite randomization there was a difference in the types of surgeries patients in each group received. For example, more patients in the control group had Ophthalmological surgery compared with aromatherapy (28 % versus 5 %). This was likely balanced by a higher portion of aromatherapy patient’s having ENT surgery." Comment: potential for error due to baseline differences between groups |

| Methods | 3‐group RCT comparing peppermint spirit vapour with inert placebo or standard antiemetics | |

| Participants | 35 women post‐cesarean section delivery. (22 peppermint/8 placebo/5 standard antiemetic). Mean age 31.3 years (range 22‐43) Inclusion criteria: "scheduled for a nonemergency C‐section, English speaking, at least 18 years of age, nonsmoker, and became nauseated post C‐section". Exclusion criteria: allergy to peppermint or food colorings, diagnosed with persistent vomiting such as hyperemesis, receiving magnesium sulphate therapy or had a condition in which the contraction of abdominal muscles during vomiting would have been contraindicated such as infected wound. Setting: community hospital, USA | |

| Interventions | Zip‐lock bag containing either pharmacy‐grade peppermint spirits ("Humco Peppermint Spirit USP: ethyl alcohol 82%, peppermint oil, purified water, peppermint leaf extract") or green‐coloured, sterile water on cotton balls. Participants in aromatherapy groups instructed to hold opened bag 2 inches under their nose and take 3 deep breaths. Standard antiemetic group received either IV ondansetron or PR promethazine depending on surgeon protocol. | |

| Outcomes | Nausea severity at initial complaint, 2, 5 min, as measured by 6‐point ordinal nausea scale (0 = no nausea, 6 = vomiting) measured by 'staff nurse' | |

| Notes | Unequal group sizes caused by allocation prior to complaints of nausea/ failure to recruit sufficient participants to account for the majority not experiencing nausea/ protocol violations and large amounts of missing/ accidentally destroyed data. Additional information requested. No information on funding source | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "...blocked systematic random assignment" method used Comment: unclear how sequence was generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The AD [admitting department] staff performed random assignment" i.e. allocation to groups done by administrative staff in separate department. Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Although the intervention and placebo were stored in identical bags and appeared identical, unblinding would have occurred on opening the bags due to the odour of the peppermint. Nurses became unblinded to the intervention and chose not to implement if it was the placebo (Quote: "nurses...did not implement the research protocol for participants in the placebo aromatherapy group.") Comment: probably not done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Clinical staff who delivered the intervention also measured the outcomes. Although the intervention and placebo were stored in identical bags and appeared identical, unblinding would have occurred on opening the bags due to the odour of the peppermint. Nurses became unblinded to the intervention and chose not to implement if it was the placebo (Quote: "nurses...did not implement the research protocol for participants in the placebo aromatherapy group.") Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Large attrition/missing data from study due in part to unblinding of intervention ("nurses...did not implement the research protocol for participants in the placebo aromatherapy group.") Some data destroyed by accident. Incomplete data recorded for several participants. Comment: likely attrition bias |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: reporting appears comprehensive, within constraints of large amounts of lost data |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: unequal group sizes likely to be a problem for statistical inference. |

| Methods | Double‐blinded cross‐over clinical trial/pilot study comparing IPA to saline placebo Setting: acute hospital, USA | |

| Participants | 15 consecutive patients in PACU who complained of nausea or vomiting after elective surgery. | |

| Interventions | Either 0.5 mL saline or 0.5 mL IPA on a cotton ball (according to random sequence) was held under participants' noses and the participant was instructed to sniff twice. If symptoms recurred, the test agents were re‐administered in random sequence. When neither test agent was effective, standard antiemetics were given and the PONV assessed every 5 min until participant left PACU | |

| Outcomes | Severity of PONV as assessed with VAS. VAS range from 0 = none to 10 = vomiting Treatment failure attributed to the last agent given. | |

| Notes | No demographic data supplied in brief report. Letter sent to study author, Dr Paul Langevin, to ask for more data, no response received. No funding source information reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "the test agents were readministered in the randomised sequence" Comment: no information on how this sequence was generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information reported on who conducted the allocation and how |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | "We designed a randomised double‐blinded study..." "Nurses who administered the test therapy were blinded to group assignment by applying an ISO‐soaked Band‐Aid under their noses while another person applied the test agent to a cotton ball, which was attached to a sponge stick." Comment: participants would not have been blinded to the treatment due to the distinctive odour of the IPA. Unclear where the 'double‐blinding' occurred |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: the published conference abstract does not specify who measured the treatment outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: original study protocol not available, no apparent losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: data reported for all participants |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: minimal data reported in this publication |

| Methods | CCT comparing IPA inhalation to standard antiemetics for treatment of PONV Setting: acute hospital, USA | |

| Participants | 39 adults having surgery. Age range: 19‐80 years; mean age = 43. Types of surgery included intra‐abdominal (29.7%), orthopaedic/extremity (23.4%), perineal (19.8%) neuro‐skeletal (10.8%), extra‐thoracic (6.3%) eyes/ears/nose/throat (6.3%), neck (3.6%) Of 40 participants evaluated for study, 21 received IPA and 18 were controls. 1 participant entered into the study had their PONV resolve spontaneously. Inclusion criteria were requirements for general anaesthesia, ability to breathe through nose before and after procedure, minimum of 18 years of age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of I, II, or III, and ability to read and write English. Exclusion criteria were allergy to IPA, alcohol abuse, no recent history of nausea or vomiting within the last 8 h, no recent intake of cefoperazone, Antabuse, or metronidazole, ability to communicate in recovery room, regional anaesthesia, and monitored anaesthesia care | |

| Interventions | IPA inhalation for treatment of PONV. "If nausea or vomiting was present in control participants, an appropriate antiemetic was given. Experimental participants were given IPA via nasal inhalation using standard hospital alcohol pads. The participant was instructed to take three deep sniffs with the pad one inch from the nose. This was repeated every five minutes for three doses or until nausea and vomiting was relieved. If nausea and vomiting continued after three doses of IPA, then an intravenous drug was given." | |

| Outcomes | Severity of PONV as measured by a DOS from "0 to 10, with 0 being no nausea or vomiting and 10 being the worst nausea and vomiting they could imagine." Cost of treatment in USD | |

| Notes | Antiemetic prophylaxis was given to participants in both groups. No information provided on funding source | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "Group assignment was alternated by day: experimental one day and control the next." Comment: study is CCT |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: allocators and caregivers appear to have been aware of the allocation. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | "Participants were blinded to which treatment they were to receive." Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: the publication does not state who measured the treatment outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: original study protocol unavailable. Stated outcomes were all addressed in report |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no apparent loss to follow‐up |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | "Only 40 of the 111 participants recruited had PONV. This is explained by aggressive prophylactic treatment at the study facility where only 7 (6.3%) of 111 participants did not receive prophylactic medication and none of these 7 participants had PONV. Additionally, the researchers speculate that pain may have been a confounding factor in accurate assessment on the DOS." Comment: several possible confounders |

| Methods | RCT comparing 70% IPA inhalation to promethazine to treat breakthrough nausea in surgical patients at high risk of PONV Setting: day hospital, USA | |

| Participants | 85 surgical patients scheduled for general anaesthesia of more than 60 minutes’ duration and having 2 of the 4 individual risk factors for PONV, (female gender, nonsmoker, history of PONV or motion sickness) (IPA group, 42; promethazine group, 43) Excluded: recent upper respiratory infection; documented allergy to IPA, ondansetron, promethazine, or metoclopramide; antiemetic or psychoactive drug use within 24 h; inability to breathe through the nose; pregnancy; history of inner ear pathology; and/or taking disulfiram, cefoperazone, or metronidazole | |

| Interventions | Control group: 12.5 mg to 25 mg IV promethazine for complaints of PONV in the PACU and SDSU and by promethazine suppository self‐administration following discharge to home Experimental group: administration of inhaled 70% IPA | |

| Outcomes | Nausea, measured by VNRS (0‐10, 0 = no nausea 10 = worst imaginable nausea) Incidence of nausea events in PACU, SDSU or at home (number) Doses of promethazine required as rescue antiemetic (number) Promethazine requirements in PACU, SDSU or at home (mg) Time in minutes to 50% reduction of nausea scores Participant satisfaction | |

| Notes | All participants received antiemetic prophylaxis prior to surgery. Study author J Pellegrini emailed to request numeric data for results published in graph form. Data received. Other clarifications requested and some were received. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "All subjects were then randomly assigned using a computer‐generated random numbers process into a control or an experimental group." Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Block randomisation was used for all of the studies using a computer generated randomisation program done by an independent party (myself) who was not involved in the data collection." (emailed study author response) Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no data on blinding. It appears that participants were aware of group allocations during study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no data on blinding. It appears that assessors were aware of group allocations during study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | "A total of 96 subjects were enrolled, but 11 subjects were withdrawn, leaving a total of 85 subjects (IPA group, 42; promethazine group, 43) whose data would be included in the final analysis. Reasons for withdrawal included 4 subjects who received additional antiemetics intraoperatively (2 in each group), 1 subject inadvertently enrolled despite being scheduled for a nasal surgical procedure (IPA group), and 6 subjects who required postoperative inpatient hospitalisation for reasons unrelated to PONV (3 in each group)." Comment: probably done |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: all outcomes stated in the article have data reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other sources of bias apparent |

| Methods | 2‐group RCT comparing peppermint spirit aromatherapy to controlled breathing | |

| Participants | 42 adult surgical patients (16 aromatherapy/26 controlled breathing) "18 years and older, male or female, of any ethnic background, ASA status I or II, able to breathe through their nose, capable of verbalizing occurrences of nausea and/or vomiting, scheduled for laparoscopic, ENT, orthopedic, or urological day surgery procedures undergoing general anaesthesia with intubation. Exclusion criteria included nausea and/or vomiting within 24 hours of admission, history of alcoholism, allergy to menthol or peppermint, weekend or emergent surgeries, department of correction clients, pregnant women, patients taking disulfiram (Antabuse) or metronidazole (Flagyl), and minors." Setting: PACU or day surgery unit, rural hospital, USA | |

| Interventions | "Upon initial complaint of PONV, either in PACU or Day Surgery, all subjects were instructed to inhale deeply through their nose to the count of 3, hold their breath to the count of 3, and exhale to the count of 3. A single treatment was composed of 3 repetitions of this deep breathing. PONV symptoms were reassessed 5 minutes after initial complaint, and if symptoms persisted a second treatment was administered. At 10 minutes following initial complaint, symptoms were reassessed." Participants randomized to aromatherapy also received peppermint spirit vapour from a vial held under their nose during controlled breathing, participants in the controlled breathing group received a similar vial without peppermint spirit. "A 13‐dram vial containing a cotton braid impregnated with 500 microlitres of pharmacy‐grade peppermint spirits (Humco, Peppermint Spirits USP: ethyl alcohol 82%, NF Grade peppermint leaf extract, peppermint oil, purified water) was placed under the nostrils at midseptum of subjects randomised to the AR group during the controlled breathing treatments. A sham vial without peppermint was used with CB subjects while they | |

| Outcomes | Nausea severity as measured by descriptive ordinal scale (0 = no nausea, 10 = worst possible nausea) at initial complaint, 5 min and 10 min. "Treatment effectiveness was equated with a DOS score of 0 postintervention. Efficacy was a measure of no postintervention antiemetic rescue desired by subjects regardless of their DOS score." | |

| Notes | Unequal group sizes, likely due to study design. Addtional information requested. No information on funding sources | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "A computer generated random number table was used to determine subject assignment" Comment: likely done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Probably not done: no documentation of allocation concealment in an otherwise well‐documented study |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: a sham aromatherapy vial without peppermint was used in the controlled breathing group, however due to the odour of the peppermint, the group allocation would have been immediately apparent to both the nurse (who delivered the treatment and assessed the outcomes) and the participant. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: a sham aromatherapy vial without peppermint was used in the controlled breathing group, however due to the odour of the peppermint, the group allocation would have been immediately apparent to both the nurse (who delivered the treatment and assessed the outcomes). |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: does not appear to have been an issue once participants had entered into the study phase. Outcome data reported for all participants who received the treatment. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | "The study evaluated a single episode of PONV whether it occurred in PACU or Day Surgery." Comment: participants who experienced multiple episodes of PONV did not have those recorded. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other sources of bias apparent |

| Methods | 3‐arm CCT of peppermint oil inhalations, peppermint essence inhalations (placebo) and no treatment (control) to treat PONV in women. Setting: acute hospital, UK | |

| Participants | 18 women undergoing major gynaecological surgery. Mean weight group 1: 152 lb [69 kg]; group 2: 139.5 lb [63 kg]; group 3: 144.2 lb [65 kg]. Mean height group 1: 64.2 inches [1.63 m]; group 2: 62.5 inches [1.58 m]; group 3: 64.3 inches [1.63 m]. Mean age group 1: 54 years; group 2: 43.2 years; group 3: 45.5 years. Participants were assessed as having no significant differences in personal characteristics, past medical history or preoperative anxiety levels. There were no statistically significant differences in preoperative fasting times, anaesthetic and recovery times or postoperative fasting times. 5 of the experimental group had intra‐abdominal surgery, compared with 3 in each of the other 2 groups. | |

| Interventions | Participants were given bottles of their assigned substance postoperatively and instructed to inhale the vapours from the bottle whenever they felt nauseous. | |

| Outcomes | Self‐reported nausea as measured by VAS of 0‐4 where 0 = "not experiencing any nausea" and 4 = "about to vomit" reported as the average score per person per day Cost of treatment in GBP Patient satisfaction with treatment, reported narratively | |

| Notes | Participants may or may not have received standard antiemetics in PACU. Study author Sylvina Tate supplied some extra data on group allocation methods. No information reported on funding sources | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "The subjects were assigned to one of three groups." Comment: study author states that participants were "randomly assigned" to ward areas |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information reported regarding concealment |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Low risk | Comment: use of peppermint essence as placebo blinded experimental and placebo group patients to treatment allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | "It was decided to use a standardized descriptive ordinal scale to collect the subjective patient self‐reported data." Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no mention of patients lost to follow‐up, however group numbers are not reported. (Group numbers clarified by author via email). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: triallists did not provide measure of statistical significance or measures of variance for daily average nausea scores, even though they state "statistically significant difference in the amount of self‐reported nausea between the placebo and experimental groups". |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Comment: due to study design, entirely possible there was some demand‐characteristic effect on patient self‐reporting of results. However, experimental group received "on average, slightly less" postoperative antiemetics and more postoperative opioids than placebo group, which would tend to indicate evidence of an effect. |

| Methods | Double‐blind RCT of IPA as a treatment for PONV. "When any episode of vomiting or nausea occurred, patients were randomised, using a random number table to receive a cotton ball soaked with ISO or saline placed under the patient’s nose by the nursing staff. The patient was instructed to sniff twice by a nurse who was blind to group assignment. It should be emphasized that the nursing staffs were instructed not to smell the content of cotton ball and to hold it away from themselves when administering to patient. If the severity of nausea or vomiting improved after a single treatment, a VAS assessment of nausea was obtained every 5 minutes until the patient was discharged or PONV symptoms recurred. Improvement of nausea was defined as a decrease of at least 40% in initial VAS score, and improvement of vomiting was defined as no further episodes of vomiting. If, after treatment, severity of nausea did not improve or retching/vomiting persisted, a second treatment with the same agent was given. Treatment sequences were repeated for a maximum of three times in a 15‐minute period. When severity of either nausea or vomiting failed to improve despite three treatments, intravenous (IV) ondansetron 0.1 mg/kg (maximum 4 mg) was administered. If symptoms persisted, a second dose of ondansetron was administered. For patients who failed to improved after two ondansetron doses (maximum dose: 8mg), other IV antiemetic medications (i.e., 200 mg/kg of metoclopramide; 10 mg/kg droperidol) were given." Setting: acute paediatric day surgery centre, USA | |

| Participants | 39 children aged 6‐16 years having surgery under general anaesthesia. ASA physical status I and II. Treatment n = 20. Control n = 19. No significant differences in demographic data across groups. Exclusions: children with a history of chronic illness or developmental delay | |

| Interventions | Inhalations of IPA or saline placebo. Intervention repeated up to 3 times. IV ondansetron was used as 'rescue therapy' if PONV continued. | |

| Outcomes |

| |

| Notes | Study author, Dr Shu‐Ming Wang contacted for any further data, however due to the age of the study there was none available. No information reported on funding sources | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "If any episode of vomiting or nausea occurred, patients were randomised, using a random number table to receive a cotton ball soaked with ISO or saline placed under the patient’s nose by the nursing staff." Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no data on who conducted the allocation and any degree of separation from the conduct of the study |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Unclear risk | "The patient was instructed to sniff twice by a nurse who was blind to group assignment." Comment: personnel probably blinded, participants probably not blinded due to odour of treatment substance |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | "The patient was instructed to sniff twice by a nurse who was blind to group assignment. It should be emphasized that the nursing staffs were instructed not to smell the content of cotton ball and to hold it away from themselves when administering to patient." Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: data reported for all participants. No apparent losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: all stated outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other sources of bias apparent |

| Methods | RCT of IPA for treatment of PONV. Participants were randomized to receive either IPA inhalations, or 4 mg ondansetron. Setting: same day surgery centre, USA | |

| Participants | 41 women aged 18‐65 years who were scheduled for diagnostic laparoscopy, operative laparoscopy or laparoscopic bilateral tubal occlusion (ASA physical status I, II or III) in a day surgery unit. Treatment n = 29, control n = 12 Exclusions: inability or impaired ability to breathe through the nose, or history of sensitivity to IPA or ondansetron, had used an antiemetic within 24 h of surgery, pregnant or breastfeeding, reported existing nausea, history of significant PONV resistant to antiemetics, using disulfiram or had a history of alcoholism | |

| Interventions | Comparison of inhaled 70% IPA to ondansetron for treatment of PONV. Ondansetron (control) group: at first request for treatment participants in this group received IV ondansetron 4 mg, repeated once in 15 min if required. 70% IPA (experimental) group: a standard alcohol prep pad was held under the participant's nose and she was instructed to take 3 consecutive deep breaths through the nose. Nausea score collected for baseline at preop, then immediately postop in PACU and at any time the participant complained of nausea. Additionally, participants who complained of nausea were assessed every 5 min following treatment for 30 min and then every 15 min until discharge from PACU. | |

| Outcomes |

| |

| Notes | This study was replicated by Cotton 2007 with the number and frequency of IPA inhalations increased. Study author J Pellegrini provided additional data via email. No funding sources reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "subjects were randomly assigned to receive inhaled 70% IPA (experimental group) or IV ondansetron (control group) for the treatment of PON" "despite the use of block randomisation" Comment: study author states via email that randomization was conducted using a computer‐generated random numbers table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Block randomisation was used for all of the studies using a computer generated randomisation program done by an independent party (myself) who was not involved in the data collection." Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | "...this did not allow us to blind the study intervention." Comment: it appears that no blinding of participants or personnel was done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | "...this did not allow us to blind the study intervention." Comment: it appears that outcome assessors were not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: it appears that data were reported for all participants, no evidence of exclusions or attrition |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: original study protocol unavailable. Despite stating collection of data on patient satisfaction with anaesthetic experience, no results for this were reported, however these data were made available by a study author via email |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other sources of bias apparent |

AD: admitting department; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CB: controlled breathing; CCT: controlled clinical trial; C‐section: cesarean section; DOS: descriptive ordinal scale; ENT: ear, nose, throat; GBP: Great Britain Pound; IPA: isopropyl alcohol; ITT: Intention‐to‐treat; ISO: isopropyl alcohol; IV: intravenous; PACU: post‐anaesthesia care unit; PON: postoperative nausea; PONV: postoperative nausea and vomiting; PP: per protocol; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RNs: registered nurses; SD: standard deviation; SDSU: same‐day surgery unit; USD: United States Dollar; VAS: visual analogue scale; VNRS: verbal numeric rating scale

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT. Not aromatherapy | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not PONV | |

| Not PONV | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Not RCT/CCT | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment | |

| Prevention of PONV, not treatment |

CCT: controlled clinical trial; PONV: postoperative nausea and vomiting; RCT: randomized controlled trial

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Aromatherapy using a nasal clip after surgery |

| Methods | Allocation: randomized |

| Participants | ≥ 18 years (adult, senior) |

| Interventions | Placebo comparator: saline and nasal clip Saline and nasal clip inhaled postoperatively Experimental: aromatherapy blend and nasal clip Aromatherapy blend and nasal clip inhaled postoperatively |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measures Duration of effectiveness of the essential oil blend (time frame: immediately to 1‐day postoperative) Evidence of effectiveness of tested aromatherapy blend in reducing symptoms of postoperative nausea as measured by participant self‐report using Likert‐type scale measure Secondary outcome measures Participant comfort using the nasal clip delivery system (time frame: immediately postop to 1‐day postop) Comfort of participants using nasal clip delivery system for aromatherapy will be measured by self‐report using Likert‐type scale |

| Starting date | June 2014 |

| Contact information | Ronald Hunt, MD 704‐604‐5031 [email protected] |

| Notes | Sponsor: Balanced Health Plus |

| Trial name or title | Effect of aromatherapy on postoperative nausea, vomiting and quality of recovery |

| Methods | Study type: interventional Study design: allocation: randomized Intervention model: parallel assignment Masking: single blind (outcomes assessor) |

| Participants | 18‐65 years (adult) |

| Interventions | Experimental: lavender aromatherapy Aromatherapy with lavender essential oil. Procedure: lavender aromatherapy The 2 drops of lavender essential oil will be dropped into the gauze and the participant will inhale it for 5 min Other name: aromatherapy with lavender essential oil Experimental: rose aromatherapy Aromatherapy with rose essential oil. Procedure: rose aromatherapy The 2 drops of rose essential oil will be dropped into the gauze and the participant will inhale it for 5 min Other name: aromatherapy with rose essential oil Experimental: ginger aromatherapy Aromatherapy with ginger essential oil. Procedure: ginger aromatherapy The 2 drops of ginger essential oil will be dropped into the gauze and the participant will inhale it for 5 min Other name: aromatherapy with ginger essential oil Placebo comparator: placebo aromatherapy Aromatherapy with pure water. Procedure: placebo aromatherapy The 2 drops of pure water will be dropped into the gauze and the participant will inhale it for 5 min Other name: aromatherapy with pure water |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measures Quality of recovery (time frame: at postoperative 24 h) Quality of recovery will be measured with Quality of recovery 40 questionnaire The change of the nausea scores (time frame: during postoperative 24 h) Nausea will be measured with verbal descriptive scale on 0‐3 Likert‐type scale (0 = no nausea, 1 = some, 2 = a lot, 3 = severe) The change of the vomiting score (time frame: during postoperative 24 h) Vomiting will be measured with verbal descriptive scale (0 = no vomiting, 1 = 1 time, 2 = 2 or 3 times, 3 = 4 times and up) Secondary outcome measures The consumption of the antiemetic drug (time frame: during postoperative 24 h) The antiemetic drug dose will be recorded |

| Starting date | April 2016 |

| Contact information | Tugba Karaman, MD +90 356 212950090 356 2129500 ext 3495 [email protected] |

| Notes |

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

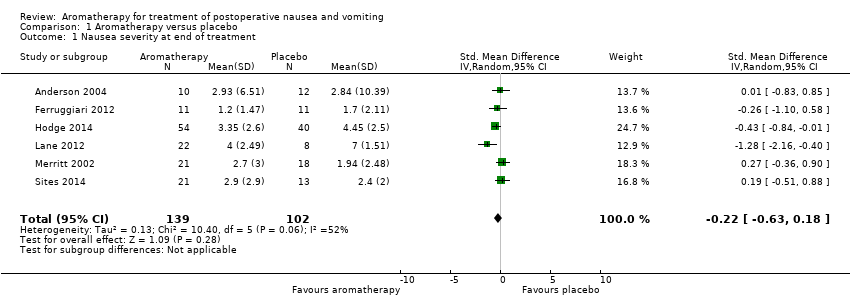

| 1 Nausea severity at end of treatment Show forest plot | 6 | 241 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.63, 0.18] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Aromatherapy versus placebo, Outcome 1 Nausea severity at end of treatment. | ||||

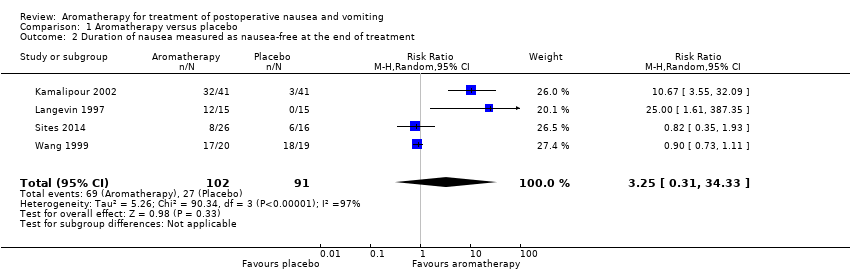

| 2 Duration of nausea measured as nausea‐free at the end of treatment Show forest plot | 4 | 193 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.25 [0.31, 34.33] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Aromatherapy versus placebo, Outcome 2 Duration of nausea measured as nausea‐free at the end of treatment. | ||||

| 3 Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics Show forest plot | 7 | 609 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.37, 0.97] |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Aromatherapy versus placebo, Outcome 3 Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Nausea severity at 5 minutes post‐initial treatment Show forest plot | 4 | 115 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.18 [‐0.86, 0.49] |

| Analysis 2.1  Comparison 2 Peppermint versus placebo, Outcome 1 Nausea severity at 5 minutes post‐initial treatment. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

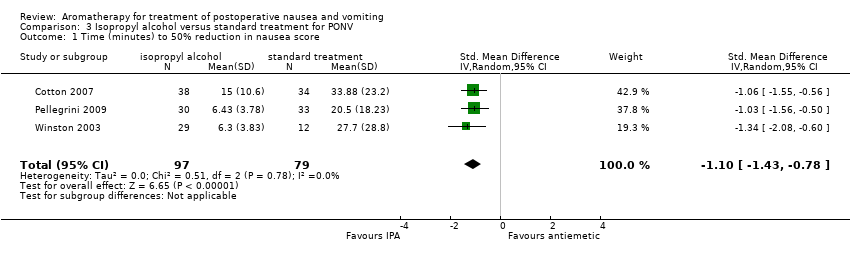

| 1 Time (minutes) to 50% reduction in nausea score Show forest plot | 3 | 176 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.10 [‐1.43, ‐0.78] |

| Analysis 3.1  Comparison 3 Isopropyl alcohol versus standard treatment for PONV, Outcome 1 Time (minutes) to 50% reduction in nausea score. | ||||

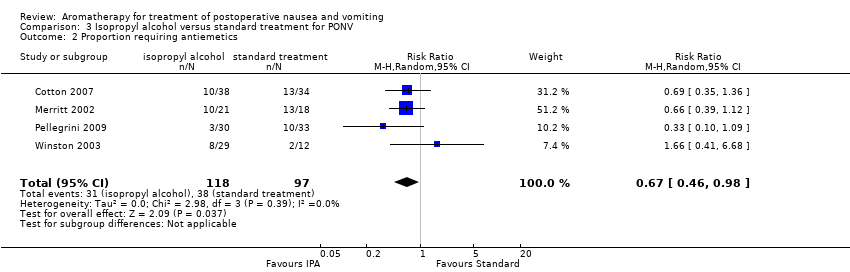

| 2 Proportion requiring antiemetics Show forest plot | 4 | 215 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.46, 0.98] |

| Analysis 3.2  Comparison 3 Isopropyl alcohol versus standard treatment for PONV, Outcome 2 Proportion requiring antiemetics. | ||||

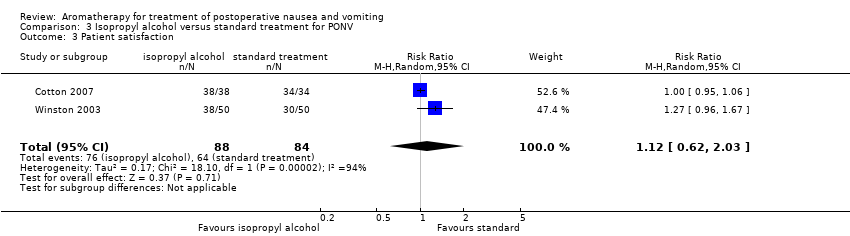

| 3 Patient satisfaction Show forest plot | 2 | 172 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.62, 2.03] |

| Analysis 3.3  Comparison 3 Isopropyl alcohol versus standard treatment for PONV, Outcome 3 Patient satisfaction. | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics Show forest plot | 4 | 291 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.12, 1.24] |

| Analysis 4.1  Comparison 4 Isopropyl alcohol versus saline, Outcome 1 Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics. | ||||

Study flow diagram

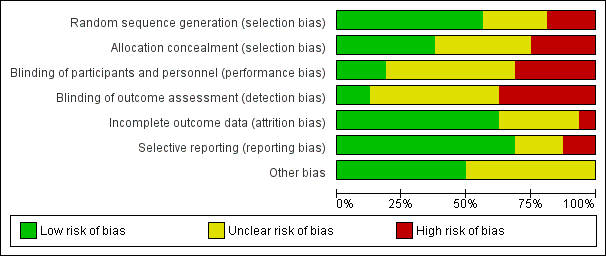

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies

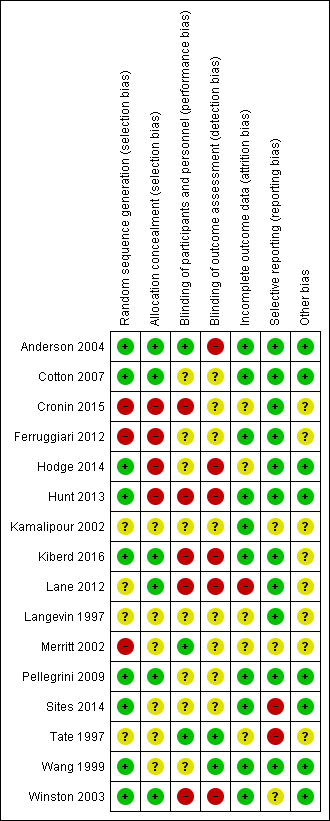

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study

Comparison 1 Aromatherapy versus placebo, Outcome 1 Nausea severity at end of treatment.

Comparison 1 Aromatherapy versus placebo, Outcome 2 Duration of nausea measured as nausea‐free at the end of treatment.

Comparison 1 Aromatherapy versus placebo, Outcome 3 Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics.

Comparison 2 Peppermint versus placebo, Outcome 1 Nausea severity at 5 minutes post‐initial treatment.

Comparison 3 Isopropyl alcohol versus standard treatment for PONV, Outcome 1 Time (minutes) to 50% reduction in nausea score.

Comparison 3 Isopropyl alcohol versus standard treatment for PONV, Outcome 2 Proportion requiring antiemetics.

Comparison 3 Isopropyl alcohol versus standard treatment for PONV, Outcome 3 Patient satisfaction.

Comparison 4 Isopropyl alcohol versus saline, Outcome 1 Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics.

| Aromatherapy compared to placebo for treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults and children having any type of surgical procedure under general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia or sedation, either as hospital inpatients or outpatients, with existing PONV | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with aromatherapy | |||||

| Nausea severity | The mean nausea severity was 2.8 (SD = 10.39) | SMD 0.22 SD lower | ‐ | 241 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Risk in placebo group based on control group in Anderson 2004 |

| Nausea duration (nausea‐free at end of treatment) Measured by participant self‐report or medical or nursing observation | Study population | RR 3.25 | 193 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | ||

| 30 per 100 | 96 per 100 | |||||

| Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics | Study population | RR 0.60 | 609 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | ||

| 68 per 100 | 41 per 100 | |||||

| Adverse events (common reactions to aromatherapy include skin rashes, dyspnoea, headache, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, hypertension or dizziness) | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment Measured by a validated scale | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Risk of bias across all studies due to study designs, downgraded one level. | ||||||

| Peppermint compared to placebo for treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults and children having any type of surgical procedure under general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia or sedation, as hospital inpatients or outpatients, with existing PONV | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with peppermint | |||||

| Nausea severity | The mean nausea severity was 2.8 (SD = 10.39) | SMD 0.18 SD lower | ‐ | 115 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Risk in placebo group based on control group in Anderson 2004 |

| Nausea duration (nausea‐free at end of treatment) Measured by participant self‐report or medical or nursing observation | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| Use of rescue antiemetics | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| Adverse events (common reactions to aromatherapy include skin rashes, dyspnoea, headache, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, hypertension or dizziness) | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment Measured by a validated scale | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Risk of bias in included studies due to study designs, downgraded one level. | ||||||

| Isopropyl alcohol compared to standard treatment for postoperative nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults and children having any type of surgical procedure under general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia or sedation, as hospital inpatients or outpatients, with existing PONV | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with standard treatment for PONV | Risk with isopropyl alcohol | |||||

| Nausea severity Measured by a validated scale or medical or nursing observation | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| Nausea duration (measured as nausea‐free at end of treatment) Measured by participant self‐report or medical or nursing observation | The mean time to 50% reduction in nausea score was 20.5 minutes | SMD 1.10 SD lower | ‐ | 176 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Risk in placebo group based |

| Use of rescue antiemetics | Study population | RR 0.67 | 215 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | ||

| 39 per 100 | 26 per 100 | |||||

| Patient satisfaction with treatment Measured by a validated scale | Study population | RR 1.12 | 172 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | ||

| 76 per 100 | 85 per 100 | |||||

| Adverse events (common reactions to aromatherapy include skin rashes, dyspnoea, headache, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, hypertension or dizziness) | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1No or unclear blinding in all included studies, downgraded one level. | ||||||

| Isopropyl alcohol compared to saline for treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults and children having any type of surgical procedure under general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia or sedation, as hospital inpatients or outpatients, with existing PONV | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect | № of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Risk with saline | Risk with isopropyl alcohol | |||||

| Nausea severity Measured by a validated scale or medical or nursing observation | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| Nausea duration (nausea‐free at end of treatment) Measured by participant self‐report or medical or nursing observation | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| Use of rescue antiemetics | Study population | RR 0.39 | 291 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | ||

| 90 per 100 | 35 per 100 | |||||

| Adverse events (common reactions to aromatherapy include skin rashes, dyspnoea, headache, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, hypertension or dizziness) | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| Patient satisfaction with treatment Measured by a validated scale | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | The studies reporting this comparison did not report this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1Poor reporting in Kamalipour 2002 and Langevin 1997 affect confidence in results, downgraded one level. | ||||||

| Study | Design | Intervention/comparison | Measure | Satisfied |

| RCT | IPA/Saline/Peppermint | 100 mm VAS (0 mm extremely dissatisfied; 100 mm fully satisfied) | IPA: 90.3 (SD: 14.9) peppermint: 86.3 (SD: 32.3) saline: 83.7 (SD: 25.6) | |

| RCT | IPA/ondansetron | 4‐point DOS (poor, fair, good, excellent) | Good or excellent: Intervention: 38/38 Comparison: 34/34 | |

| RCT | IPA/Promethazine | 5‐point DOS (1 = totally unsatisfied, 5 = totally satisfied) | Both groups reported median score 4 | |

| RCT | IPA/ondansetron | 4‐point DOS (poor, fair, good, excellent) | Good or excellent: Intervention: 38/50 Comparison: 30/50 | |

| DOS: descriptive ordinal scale; IPA: isopropyl alcohol; RCT: randomized controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; VAS: visual analogue scale | ||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Nausea severity at end of treatment Show forest plot | 6 | 241 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.63, 0.18] |

| 2 Duration of nausea measured as nausea‐free at the end of treatment Show forest plot | 4 | 193 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.25 [0.31, 34.33] |

| 3 Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics Show forest plot | 7 | 609 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.37, 0.97] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Nausea severity at 5 minutes post‐initial treatment Show forest plot | 4 | 115 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.18 [‐0.86, 0.49] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Time (minutes) to 50% reduction in nausea score Show forest plot | 3 | 176 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.10 [‐1.43, ‐0.78] |

| 2 Proportion requiring antiemetics Show forest plot | 4 | 215 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.46, 0.98] |

| 3 Patient satisfaction Show forest plot | 2 | 172 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.62, 2.03] |

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Proportion requiring rescue antiemetics Show forest plot | 4 | 291 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.12, 1.24] |