Terapias osmóticas agregadas a los antibióticos para la meningitis bacteriana aguda

References

References to studies included in this review

References to studies excluded from this review

Additional references

References to other published versions of this review

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Adults with bacterial meningitis (clinical suspicion of meningitis plus CSF evidence of infection: > 100 white cells/mm³, predominately neutrophils, a positive gram stain or cloudy CSF) | |

| Interventions | Oral glycerol 75 mg in 135 mL Oral glucose 50% solution 135 mL | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: mortality Secondary outcomes: epilepsy, deafness, residual neurological deficit at day 40 | |

| Notes | Source of funding: the Meningitis Research Foundation Placebo is potentially not completely inactive and 50% glucose may exert a neurological effect in meningitis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "A randomisation number list in blocks of 12 was produced by an independent statistician using Stata version 9.0" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Numbers and allocation were placed into sealed envelopes. Envelopes were opened sequentially by an independent person not involved in the clinical care or assessment of trial participants" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | "Triple blinded" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Intention‐to‐treat analysis; all participants included in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | None apparent |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases apparent |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with 4 arms | |

| Participants | Children from 3 months to 15 years of age with bacterial meningitis (CSF culture positive; CSF leucocytes > 100/mm²; positive blood culture in a child with signs and symptoms of bacterial meningitis) | |

| Interventions | Glycerol 4.5 g/kg to a maximum 180 g/day divided into 3 doses/24 hours. Increased by 50% for dose 1 and decreased by 50% for dose 2. No details of placebo given. Treatment given for 3 days Dexamethasone 1.5 mg/kg once daily IV divided into 3 doses/24 hours. 50% dose adjustments as per glycerol also used. Treatment given for 3 days 4 groups used, glycerol, glycerol + dexamethasone, dexamethasone and "neither" | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: mortality Secondary outcomes: epilepsy, deafness, residual neurological deficit | |

| Notes | Source of funding: the Arvo and Lea Ylppö Foundation, Helsinki, Finland, and Roche Oy, Helsinki, Finland No details given of whether any placebo agent was used | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "A computer generated list of random therapy assignments was kept at the children's hospital" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The next adjunctive treatment regimen was obtainable by telephone 24 hours a day" It was not clear if this person giving the assignments was part of the study team or independent |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | No details of blinding were given, so we assumed the study was unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | 134 children enrolled, 12 excluded, 122 in the final series but only 120 analysed. Details of the missing data were not present in the text |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No details of the missing data given, so it is not clear if selective cases are presented |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups not completely matched: more females in the dexamethasone group and increased meningitis due to S pneumoniae in the control group |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with 4 arms | |

| Participants | Children aged 2 months or older with bacterial meningitis (CSF culture positive; CSF leucocytes ≥ 100/mm² with positive blood culture; CSF ≥ 100 leukocytes with signs and symptoms of bacterial meningitis) | |

| Interventions | 1. Glycerol + paracetamol 2. Glycerol 3. Paracetamol 4. Placebo All placebo‐controlled: carboxymethylcellulose (placebo for glycerol) and cocoa butter base suppository (placebo for paracetamol) Doses: glycerol 6 g/kg/day in 4 daily doses (maximum 2.5 mg/dose) for 2 days Acetaminophen rectal suppository 35 mg/kg first dose followed by 20 mg/kg 6‐hourly for 42 hours | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome:

Secondary outcomes:

| |

| Notes | Source of funding: the Academy of Finland In the trial registration from 2008, the primary outcomes were: death, severe neurological sequelae and hearing loss; secondary outcomes were: audiological or neurological sequelae | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "...randomisation was computer generated in permuted blocks of 12" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | No report in trial. Email from author that the trial was "double blind" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Intention‐to‐treat analysis; all participants included in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | None apparent. Some differences between trial report and trial registration |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No detailed baseline characteristics: "baseline data for the 4 groups were similar except more children had received antibiotics in the paracetamol + glycerol group" |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with 4 arms, multicentre in South America | |

| Participants | Children aged 2 months to 16 years with bacterial meningitis (CSF culture positive, "characteristic CSF findings" with a positive blood culture or CSF positive with latex antigen test; symptoms and signs of bacterial meningitis with at least 3 of the following: CSF white cell count > 1000 cells/mm³, CSF glucose < 40 mg/dL, CSF protein > 40 mg/dL, blood white cell count >15,000 cells/mm³ | |

| Interventions | Glycerol 1.5 g/kg in an 85% solution divided into 3 doses/24 hours. Treatment given for 2 days Placebo: saline plus carboxy methylcellulose. Doses and volumes of placebo not given in the paper Dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg once daily IV divided into 3 doses/24 hours. Treatment given for 2 days 4 groups: glycerol + placebo, glycerol + dexamethasone, dexamethasone + placebo and placebo + placebo | |

| Outcomes | Primary mortality. No secondary mortality at the end of follow‐up given Secondary outcomes: epilepsy, deafness and residual neurological deficit | |

| Notes | Source of funding: GlaxoSmithKline, Alfred Kordelin, Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg, and Sigfrid Jusélius Funds. Farmacia Ahumada donated glycerol and both placebo preparations. Laboratorio de Chile partly donated ceftriaxone. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Stratified block randomisation took place in blocks of 20" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "All treatment kits were packaged according to the randomisation lists in Santiago, Chile. Saline and carboxymethylcellulose were the placebo preparations for dexamethasone and glycerol, respectively. The agents were provided in identical ampoules or bottles and were labelled only with a study code" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | "All treatment kits were packaged according to the randomisation lists in Santiago, Chile. Saline and carboxymethylcellulose were the placebo preparations for dexamethasone and glycerol, respectively. The agents were provided in identical ampoules or bottles and were labelled only with a study code" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | None identified |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No missing data identified |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Drugs were supplied by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Farmacia Ahumada. GSK partially funded the study |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Single centre | |

| Participants | Children aged 2 months to 12 years with bacterial meningitis (positive CSF culture or CSF latex agglutination positive, or CSF cytology with a suggestive biochemical profile with fever and signs of CNS involvement) | |

| Interventions | Glycerol 1.5 g/kg IV or orally 6‐hourly. Placebo carboxymethyl cellulose 2% solution IV. Total dose of placebo not given just documented "matched". Dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg 6‐hourly. Duration of treatment not reported | |

| Outcomes | Primary mortality. No secondary mortality at the end of follow‐up given Secondary outcomes: epilepsy, deafness and residual neurological deficit | |

| Notes | Source of funding: reported as "Nil" This study was published twice, with a preliminary analysis of the osmotic effects published as Singhi 2008 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation list prepared with a simple random numbers table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Serially numbered, sealed packets prepared, kept readily available |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Clinicians and participants blinded. It was not clear from the text if the investigators were fully blinded but the packets were prepared by a separate person from the investigating team |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Outcome data were complete |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No data were reported for important outcomes: adverse events and time for stopping treatment |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases apparent |

CNS ‐ central nervous system; CSF ‐ cerebrospinal fluid; IV ‐ intravenous

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

Jump to:

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Case series of mannitol used for bacterial meningitis. No randomisation or placebo use documented | |

| RCT of newborns with bacterial meningitis receiving oral glycerol versus standard treatment. Eligible for inclusion, but the trial was suspended. This was confirmed by the trialists | |

| Not a RCT: retrospectively identified controls. Osmotherapy (hypertonic saline) was one of the interventions | |

| Not a RCT. Glycerol use discussed | |

| Open‐label RCT of children with raised intracranial pressure due to acute CNS infections, including meningitis receiving fluid and vasoactive therapy to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure above 60 mm Hg versus hyperventilation and osmotherapy to maintain intercranial pressure below 20 mm Hg | |

| Review article. Glycerol use discussed | |

| Literature review and documented personal experience of the use of mannitol in meningitis | |

| Retrospective cohort study examining patients with bacterial meningitis 1987 to 2009 who were treated with dexamethasone, mannitol and phenytoin. No data were collected prospectively and participants were not randomised to receive any of the interventions | |

| Review article. Glycerol use discussed | |

| Review article. Not a RCT | |

| Letter in response to the journal editorial summary of Peltola 2007 | |

| Mannitol tested for neurosurgical infections and not acute bacterial meningitis. Not a RCT | |

| Systematic review. Glycerol use discussed |

CNS ‐ central nervous system; RCT ‐ randomised controlled trial

Data and analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

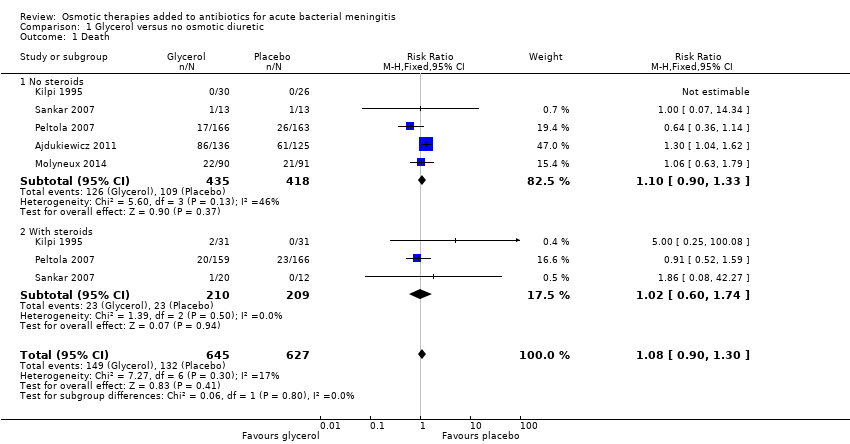

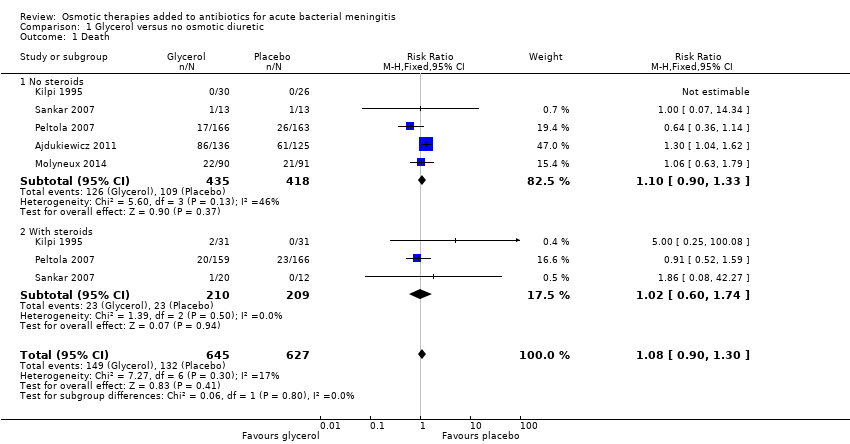

| 1 Death Show forest plot | 5 | 1272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.90, 1.30] |

| Analysis 1.1  Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 1 Death. | ||||

| 1.1 No steroids | 5 | 853 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.90, 1.33] |

| 1.2 With steroids | 3 | 419 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.60, 1.74] |

| 2 Neurological disability Show forest plot | 5 | 1270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.53, 1.00] |

| Analysis 1.2  Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 2 Neurological disability. | ||||

| 2.1 No steroids | 5 | 851 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.49, 1.01] |

| 2.2 With steroids | 3 | 419 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.38, 1.77] |

| 3 Seizures Show forest plot | 4 | 1090 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.90, 1.30] |

| Analysis 1.3  Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 3 Seizures. | ||||

| 3.1 No steroids | 4 | 755 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.92, 1.44] |

| 3.2 With steroids | 2 | 335 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.70, 1.33] |

| 4 Hearing loss Show forest plot | 5 | 922 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.44, 0.93] |

| Analysis 1.4  Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 4 Hearing loss. | ||||

| 4.1 No steroids | 4 | 572 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.41, 0.99] |

| 4.2 With steroids | 3 | 350 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.32, 1.35] |

| 5 Adverse effects: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea Show forest plot | 2 | 851 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.81, 1.47] |

| Analysis 1.5  Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 5 Adverse effects: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea. | ||||

| 5.1 No steroids | 2 | 546 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.81, 1.83] |

| 5.2 With steroids | 1 | 305 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.66, 1.13] |

| 6 Adverse effects: gastrointestinal bleeding Show forest plot | 3 | 607 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.39, 2.19] |

| Analysis 1.6  Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 6 Adverse effects: gastrointestinal bleeding. | ||||

| 6.1 No steroids | 3 | 296 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.06, 2.60] |

| 6.2 With steroids | 3 | 311 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.44, 3.04] |

Study screening flow diagram

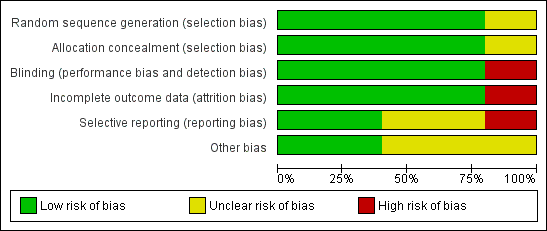

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 1 Death.

Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 2 Neurological disability.

Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 3 Seizures.

Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 4 Hearing loss.

Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 5 Adverse effects: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea.

Comparison 1 Glycerol versus no osmotic diuretic, Outcome 6 Adverse effects: gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Glycerol for acute bacterial meningitis | ||||||

| Patient or population: children and adults with acute bacterial meningitis | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect | Number of participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Glycerol | |||||

| Death | 19 per 100 | 21 per 100 | RR 1.08 | 1272 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Downgraded for imprecision. Glycerol probably has little or no effect on death |

| Neurological disability | 9 per 100 | 6 per 100 (5 to 9) | RR 0.73 (0.53 to 1.00) | 1270 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,3,4,5 | Downgraded for imprecision and inconsistency. Glycerol may reduce disability |

| Seizures | 32 per 100 | 35 per 100 | RR 1.08 | 1090 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | Downgraded for inconsistency and imprecision. Glycerol may have little or no effect on seizures |

| Hearing loss | 16 per 100 | 10 per 100 | RR 0.64 | 922 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Downgraded for imprecision. Glycerol probably reduces hearing loss |

| Adverse effects: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea | 47 per 100 | 51 per 100 (38 to 69) | RR 1.09 (0.81 to 1.47) | 851 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | Downgraded for serious inconsistency and imprecision. The effect of glycerol on adverse events: nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea is uncertain |

| Adverse effects: gastrointestinal bleeding | 3 per 100 | 3 per 100 (13 to 8) | RR 0.93 (0.39 to 2.19) | 607 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | Downgraded for imprecision. Glycerol probably has little or no effect on adverse events: gastrointestinal bleeding |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval (CI)) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence | ||||||

| 1No serious risk of bias: allocation concealment was adequate in four trials and unclear (not reported) in one trial. 3Not downgraded for indirectness. The five trials were conducted in Finland, Malawi, India and South America. Four were in children and one in adults. All included patients with suspected meningitis and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) changes suggestive of bacterial infection. 5Downgraded by one level for inconsistency: in the Finnish trial the risk of neurological sequelae was reduced with glycerol (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.78, N = 329), but this was not found in the other studies and the meta‐analysis did not detect a difference (I² = 59%). 6Downgraded by one level for inconsistency: in the trial with adults the risk of seizures was higher with glycerol (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.23, N = 250), but this was not found in the other studies and the meta‐analysis did not detect a difference (I² = 62%). 8Another two trials reported on this outcome but the results could not be added to the meta‐analysis; one reported more cases of vomiting with glycerol and the other that the incidence of vomiting was "similar" in the treatment groups. 9Downgraded by two levels for inconsistency: in the South American and Finnish trials the risk of adverse effects was increased with glycerol, but this was not found in the Malawi and India trials, and the meta‐analysis did not detect a difference (I² = 79%). | ||||||

| Drug | Class | Mechanism of action | Dose range and route | Studied/used in |

| Glycerol | Sugar alcohol | Probably osmosis plus possible vascular and metabolic benefit | IV 5% to 10% solution or 50 g Oral 1.5 g/kg | Meningitis (Peltola 2007), stroke (Righetti 2004) |

| Mannitol | Sugar alcohol | Osmotic diuretic | IV 20% solution 1 mL/kg to 10 mL/kg or 1 g/kg | Brain trauma (Wakai 2013), cerebral malaria (Namutangula 2007), stroke (Bereczki 2007)

|

| Sorbitol | Sugar alcohol | Osmotic diuretic (weak) | Oral, IV | Experimental brain perfusion, stroke |

| Hypertonic saline | Hypertonic solutions | Osmosis | IV | Brain trauma (Choi 2005), stroke (Schwarz 2002) |

| Sodium lactate | Hydroxy acids | Osmosis (weak) | IV | Brain trauma (Ichai 2009) |

| IV: intravenous | ||||

| Name of study | Population | Intervention and dose | Control used | Treatment duration | Study arms |

| Children in Finland | Oral glycerol 4.5 g/kg max 180 g/24 h in 3 divided doses Dexamethasone (dex) 1.5 mg/kg max 60 mg/day | No oral placebo IV saline | 3 days | 4 arms: IV dexamethasone + glycerol, oral glycerol, IV dexamethasone, neither treatment | |

| Children in India | Oral glycerol 1.5 g/kg 3 x daily Dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg 3 x daily | Oral carboxymethylcellulose 2% IV saline | Not detailed | 4 arms: placebo oral and IV, IV dexamethasone + oral glycerol, IV placebo + oral glycerol, IV dexamethasone + oral placebo | |

| Children in South America | Oral glycerol 1.5 g/kg 3 x daily Dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg 3 x daily | Oral carboxymethylcellulose 2% IV saline | 2 days | 4 arms: oral and IV placebo, IV dexamethasone + oral glycerol, IV placebo + oral glycerol, IV dexamethasone + oral placebo | |

| Adults in Malawi, Southern Africa | Oral glycerol 75 mg 4 x daily diluted in water or 50% dextrose solution | Oral 50% dextrose solution | 4 days | Oral glycerol versus oral 50% dextrose | |

| Children in Malawi, Southern Africa | Oral glycerol 25 mL/dose (maximum dose) = 100 mL/24 hours. Acetaminophen 35 mg/kg 6‐hourly | Oral carboxymethylcellulose 2% | 2 days | 3 arms: oral glycerol and oral acetaminophen, oral placebo and glycerol, oral acetaminophen and oral placebo | |

| IV: intravenous | |||||

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

| 1 Death Show forest plot | 5 | 1272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.90, 1.30] |

| 1.1 No steroids | 5 | 853 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.90, 1.33] |

| 1.2 With steroids | 3 | 419 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.60, 1.74] |

| 2 Neurological disability Show forest plot | 5 | 1270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.53, 1.00] |

| 2.1 No steroids | 5 | 851 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.49, 1.01] |

| 2.2 With steroids | 3 | 419 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.38, 1.77] |

| 3 Seizures Show forest plot | 4 | 1090 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.90, 1.30] |

| 3.1 No steroids | 4 | 755 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.92, 1.44] |

| 3.2 With steroids | 2 | 335 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.70, 1.33] |

| 4 Hearing loss Show forest plot | 5 | 922 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.44, 0.93] |

| 4.1 No steroids | 4 | 572 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.41, 0.99] |

| 4.2 With steroids | 3 | 350 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.32, 1.35] |

| 5 Adverse effects: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea Show forest plot | 2 | 851 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.81, 1.47] |

| 5.1 No steroids | 2 | 546 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.81, 1.83] |

| 5.2 With steroids | 1 | 305 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.66, 1.13] |

| 6 Adverse effects: gastrointestinal bleeding Show forest plot | 3 | 607 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.39, 2.19] |

| 6.1 No steroids | 3 | 296 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.06, 2.60] |

| 6.2 With steroids | 3 | 311 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.44, 3.04] |