Terapia del habla y el lenguaje para la afasia posterior al accidente cerebrovascular

References

Referencias de los estudios incluidos en esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios excluidos de esta revisión

Referencias de los estudios en espera de evaluación

Referencias de los estudios en curso

Referencias adicionales

Referencias de otras versiones publicadas de esta revisión

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Multicentre RCT stratified by severity of communication impairment and recruiting site, UK | |

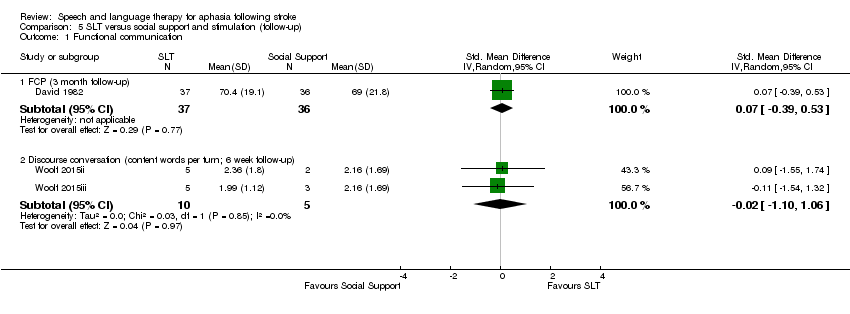

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: communication impairment as a result of aphasia, therapist considers able to engage in therapy and likely to benefit, consent Exclusion criteria: subarachnoid haemorrhage, dementia, learning disabilities, non‐English speaker, serious comorbidity, unable to complete screening procedure within 3 attempts or 2 weeks, family or caregiver objection, therapist assessment required prior to trial screening Group 1: 76 participants Group 2: 77 participants Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

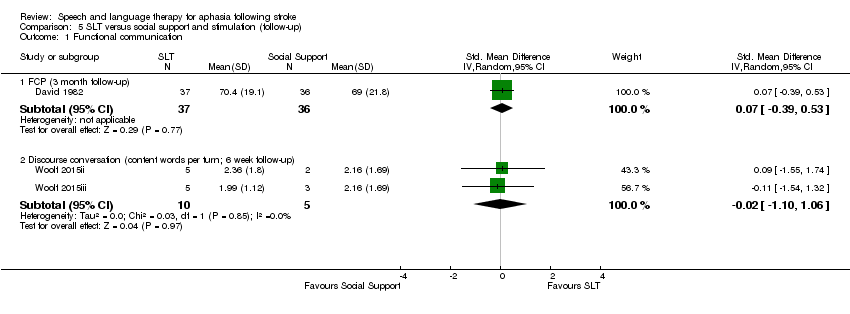

| Interventions | 1. Conventional SLT Intervention: speech and language therapy. Materials: communication charts, personalised advice booklet, session record, patient life book, AAC devices. Procedures: manualised (assessment, information provision, provision of communication materials, caregiver contact, indirect contact (with MDT), direct contact). Direct remediation of speech and language: impairment (hypothesis‐driven approach to rehabilitation of language skills), activity (compensatory strategies and conversational skills training), and participation (specific exercises) approaches. Promotion of alternative means of communication, support adjustment to communication impairment, improving communication environment. Provided by: 4 therapists. Led by highly experienced speech and language therapists plus delivery by other therapists. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face, clinic or home. Regimen: Per protocol. 3 sessions (varied length) weekly up to 16 weeks. Delivered average of 22 sessions (18 h) over 13 weeks. Tailoring: individualised. Modification: therapy amount. Adherence: monitored. 2. Social support and stimulation Intervention: 9 part‐time paid trained visitors. Attention control. Materials: approved board games and activities. Procedures: manualised. Participant‐led. Everyday activities building rapport including general conversation and activities (reading to the participant, watching television, playing board games (e.g. chess), creative activities, gardening) TV, music. Plus sessions to prepare participants for cessation of visits. Provided by: trained paid visitors. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face, hospital and at home. Regimen: Per protocol up to 3 sessions (varied length up to 60 mins) weekly for 16 weeks. Delivered max 45 sessions (average 15 h; 1‐45 contacts, max 41 h) up to 16 weeks. Tailoring: yes. Individualised. Modification: amount of visits (above). Adherence: monitored | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: functional communication; expert blinded therapist rating of semi‐structured conversation using TOMs Data collection: baseline and 6 months postrandomisation | |

| Notes | Additional participants with dysarthria (no aphasia) were also randomised to the 2 interventions, but data from these individuals have not been included within this review Dropouts are detailed in Table 2 Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | External, independent, web‐based, stratified by severity of communication impairment (TOM) and recruiting site |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | External, independent, web‐based |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Primary outcome rated by expert therapists blinded to allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Dropouts accounted for ITT employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Groups comparable at baseline Sample size calculation reported |

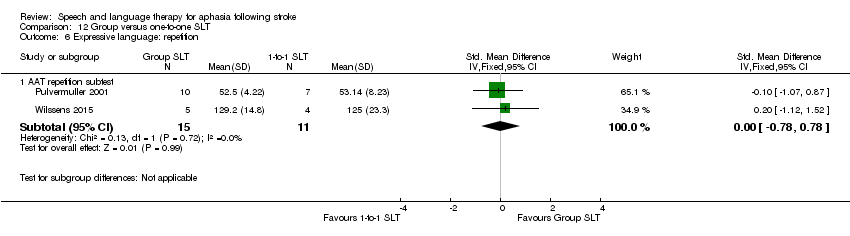

| Methods | Single‐centre cross‐over RCT, stratified by matched pairs, Germany | |

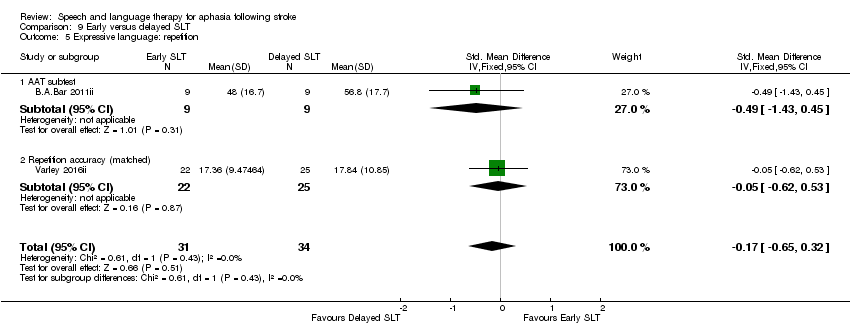

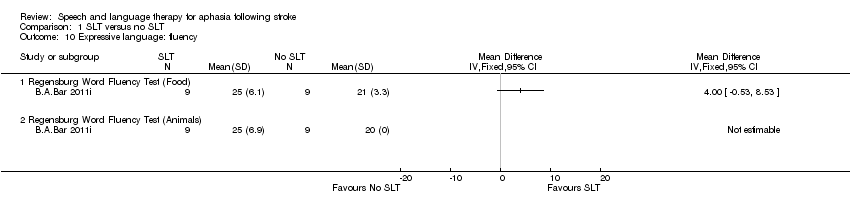

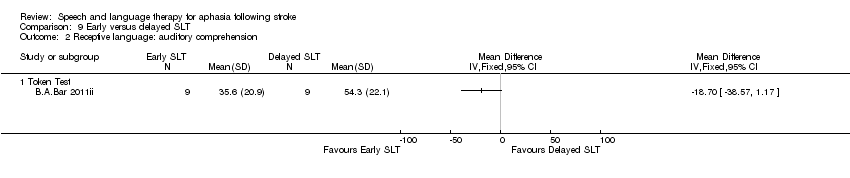

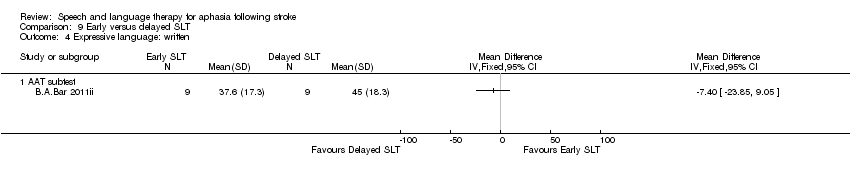

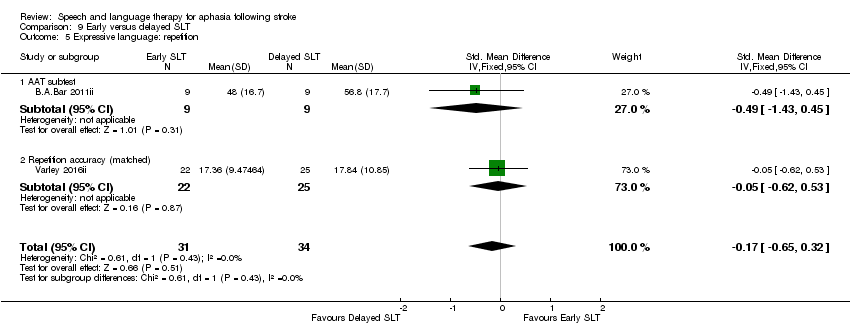

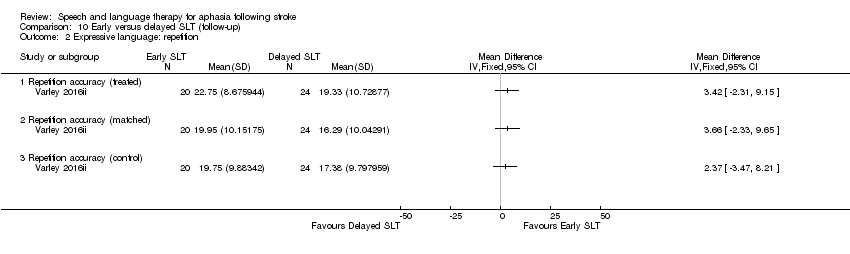

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: moderate to severe aphasia (score on the AAT naming subtest below a percentile rank of 50; and comprehension on the repetition and speech AAT sub‐tests exceeding percentile rank of 30); vascular aetiology; stable general health condition; duration of aphasia of at least 4 months, with severe‐to‐moderate word finding difficulties, irrespective of fluent or nonfluent language production. The criteria also required the participants to be able to understand and repeat simple word stimuli and the existence of no or only minimal motor speech disorder (dysarthria, apraxia of speech, or both). Passed exploratory B.A.Barr training of 60 min over 2 weeks Exclusion criteria: severe semantic disorder or comprehension problems (< 30% rank of the AAT speech comprehension test), severe motor speech disorder or apraxia Group 1: 9 participants Group 2: 9 participants Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Supervised intensive language self training Intervention: computer SLT. Designed to facilitate dialogue skills in everyday life, use of adjacency pairs (Schegloff 2007). The turns are functionally related to each other (e.g. greeting–greeting: "Hello"–"Hi"; leave‐taking‒leave‐taking: "Goodbye"–"Bye!") or information acts (e.g. question–answer: "When is the doctor's office open?"–"From 2 until 5 p.m."). The guiding principle is "talk‐in‐interaction" (Schegloff 2004). Materials: B.A.Bar equipment. Simple electronic device makes use of barcodes that carry linguistic information suited to language learning. Speech of various levels of complexity (words, phrases, sentences, texts) can be recorded, stored, and replayed as often as needed during learning. When a barcode is scanned, the recorded language is replayed to facilitate reproduction. The learning material consisted of short dialogues composed of 3 adjacency pairs: a conventional beginning (e.g. greeting–greeting), a main information part (e.g. question–answer, offer–affirmation), and a conventional ending (e.g. leave‐taking‒leave‐taking). Each half‐day training of dialogues had to be complemented by corresponding vocabulary drill exercises that required auditory word comprehension (word–picture matching) and oral naming.The items were always related to the topics conveyed by the dialogues. The 2 tasks were again carried out by means of barcode scanning. Moreover, the drill exercises contained 6 to 8 items for oral naming and 6 items for comprehension. Procedures: weekly supervision of the home training. B.A.Bar dialogue training. Exercise sheets with dialogues were given to the participants so that learners with aphasia could placethemselves in the role of the responding partner. The home training material consisted of 48 dialogues that represented characteristic scenes from 2 different thematic fields of daily living. Half of the dialogues were related to shopping, food, and drinking, the other half to health and illness. For each thematic field, a separate booklet with practice material containing 24 dialogues was prepared. Booklets were separated into 4 chapters with 2 subchapters each. The participants were instructed to practice the 8 subchapters in sequence, 1 in the morning and 1 in the afternoon, 4 d a week. Thus, every half day, 3 dialogues had to be practiced. During the 4‐week training, the total material was practiced twice: the first thematic field during the 1st and 3rd week and the second thematic field during the 2nd and 4th week. Provided by: B.A.Bar Equipment, which reads barcodes provided to therapists in private practice for use with randomised patients. Each therapist received 1 h of training before participant began to use B.A.Barr. Delivery: computer‐facilitated, 1 participant using 1 computer at home plus 1 h in clinic with therapist (and no computer). Regimen: practice twice a day for 1 h per session, 4 d per week (for 4 weeks) plus 1 h private session with speech and language therapist. Tailoring: yes. Modification: SLT focused on items described as difficult by patient and selected dialogues practiced. Adherence: monitored through supervision once a week by speech and language therapist in private practice and supported through dialogue, roleplay, review of difficult items, planning of future sessions, self evaluation forms from therapists. 2. Visual‐cognitive tasks Intervention: no SLT. Attention control. Materials non‐linguistic cognitive training focused on basic functions of visual exploration and attention. It involved visual–cognitive exercises such as visual matching of a part to the whole, maze games, comparing 2 pictures to find differences, or searching for target objects in complex pictures. A separate booklet of worksheets was developed for each week of training, again—like the language training—separated into 4 chapters and 8 subchapters. During the 4‐week treatment, the total visual–cognitive material was also practiced twice, the first booklet during the 1st and 3rd week and the second booklet during the 2nd and 4th week. Similar to the language training, the participants recorded the practice time after each session on protocol sheets. Each individual training session was based on a subchapter of the booklet containing 15 exercises: 5 pictures with visual differences, 4 maze games, 3 matching exercises, and 3 searching exercises. The time required to complete 1 session of cognitive training was calculated to be equal to the time needed for 1 session of B.A.Bar language training (approximately 30 min each). It should be noted that the B.A.Bar technology was not used during cognitive training, and feedback on correct solutions was given only during supervision but not during the home training. Procedures: visual–cognitive exercises. Provided by: speech and language therapist supervision, professional. Delivery: 1‐to‐1 and self management; face‐to‐face and self management, at home plus 1 h in clinic. Regimen: practice twice a day for 1 h per session, 4 d per week (for 4 weeks) plus 1 h private clinic session with speech and language therapist. Total dose = 36 h. Tailoring: yes. Modification: cognitive problem‐solving strategies were checked, and alternative strategies were shown to the participants. Adherence: monitored through supervision once a week by speech and language therapist in private practice and supported through diaglogue, roleplay, review of difficult items, planning of future sessions, self evaluation forms from therapists. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: dialogue test for communicative success and linguistic accuracy Data collection: baseline, T1, T2, T3, follow‐up assessment at 12 weeks | |

| Notes | Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Members of each pair were randomly assigned to groups |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Speech and language therapist blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups comparable at baseline for gender, age, duration of aphasia, and severity and type of aphasia according to performance on the AAT Power calculation confirmed (unpublished data). |

| Methods | Single‐centre cross‐over RCT, stratified by matched pairs, Germany | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: moderate to severe aphasia (score on the AAT naming subtest below a percentile rank of 50; and comprehension on the repetition and speech AAT sub‐tests exceeding percentile rank of 30); vascular aetiology; stable general health condition; duration of aphasia of at least 4 months, with severe‐to‐moderate word finding difficulties, irrespective of fluent or nonfluent language production. The criteria also required the participants to be able to understand and repeat simple word stimuli and the existence of no or only minimal motor speech disorder (dysarthria, apraxia of speech, or both). Passed exploratory B.A.Barr training of 60 min over 2 weeks Exclusion criteria: severe semantic disorder or comprehension problems (< 30% rank of the AAT speech comprehension test), severe motor speech disorder or apraxia Group 1: 9 participants Group 2: 9 participants Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

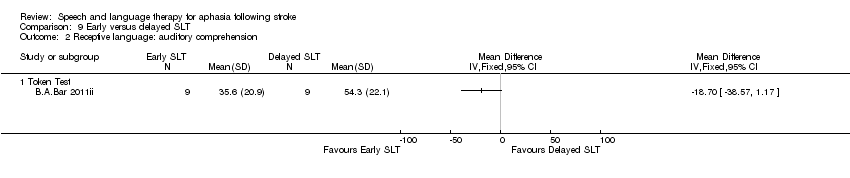

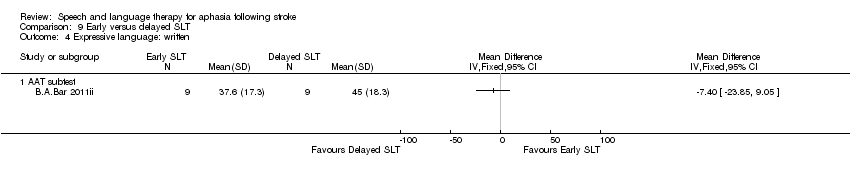

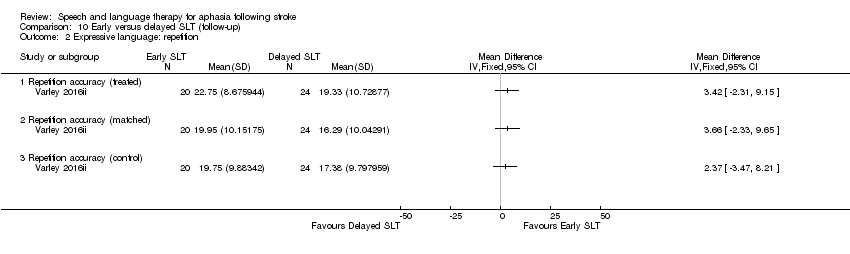

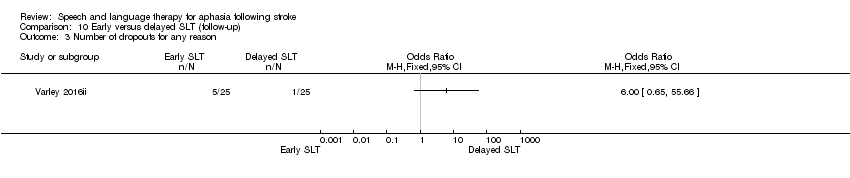

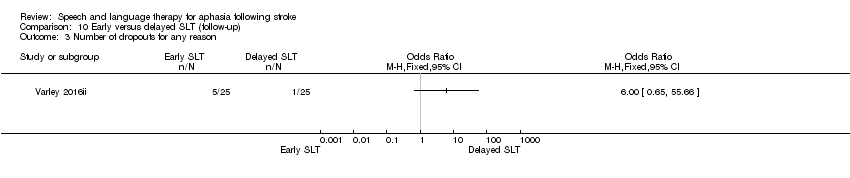

| Interventions | 1. B.A.Bar Early + visual‐cognitive exercises Intervention: early SLT. Supervised intensive language self training followed by home training with visual‐cognitive exercises. Materials: described in B.A.Bar 2011i. Procedures: described in detail in B.A.Bar 2011i. Provided by: described in detail in B.A.Bar 2011i. Delivery: 1 to computer or workbook, B.A. Bar Equipment, which reads barcodes, computer‐facilitated and workbooks at home, followed by period of self management and face‐to‐face, at home plus 1 h in clinic followed by cognitive training at home. Regimen: practice twice a day for 1 h per session, 4 d per week (for 4 weeks) plus 1 h private clinic session with therapist. Total dose = 32 h. B.A. Bar + 4 h with speech and language therapist working on dialogue training in roleplays without B.A. Bar + 32 h of visual‐cog therapy + 4 h of speech and language therapist looking at cognitive training strategies. Tailoring: yes. Modification: speech and language therapist focused on items described as difficult by participant and selected dialogues practiced. Adherence: not reported 2. Supervised home training with visual‐cognitive exercises followed by delayed intensive language self training Intervention: delayed SLT. Materials: computer SLT and home training (described in B.A.Bar 2011i). Procedures: described in detail in B.A.Bar 2011i. Provided by: described in detail in B.A.Bar 2011i. Delivery: 1 to computer or workbook, B.A. Bar Equipment, which reads barcodes, computer‐facilitated and workbooks at home, followed by period of self management and face‐to‐face, at home plus 1 h in clinic followed by cognitive training at home.Regimen: practice twice a day for 1 h per session, 4 d per week (for 4 weeks) plus 1 h private clinic session with speech and language therapist. Total dose = 32 h B.A. Bar + 4 h with speech and language therapist working on dialogue training in roleplays without B.A. Bar plus 32 h of visual‐cognitive therapy + 4 h of speech and language therapist looking at cognitive training strategies. Tailoring: yes. Modification: speech and language therapist focused on items described as difficult by participant and selected dialogues practiced. Adherence: not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: dialogue test for communicative success and linguistic accuracy Data collection: baseline, T1, T2, T3, follow‐up assessment at 12 weeks | |

| Notes | Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Members of each pair were randomly assigned to groups |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Speech and language therapist blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups comparable at baseline for sex, age, duration of aphasia, and severity and type of aphasia according to performance on the AAT Power calculation not reported |

| Methods | RCT, UK | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: first stroke, below normal on WAB, native English speaker, medically stable, fit for participation Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

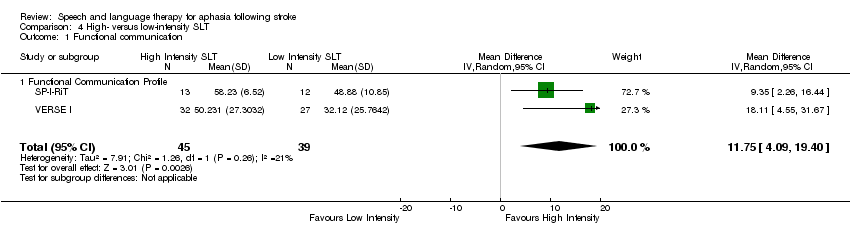

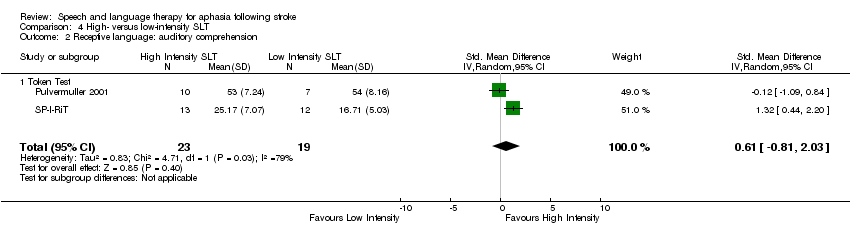

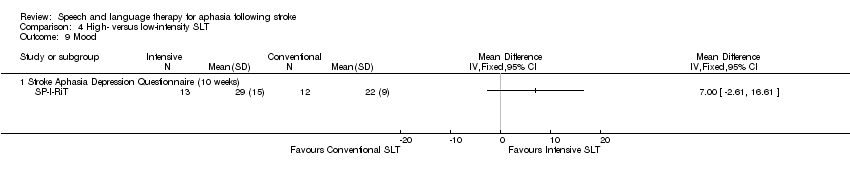

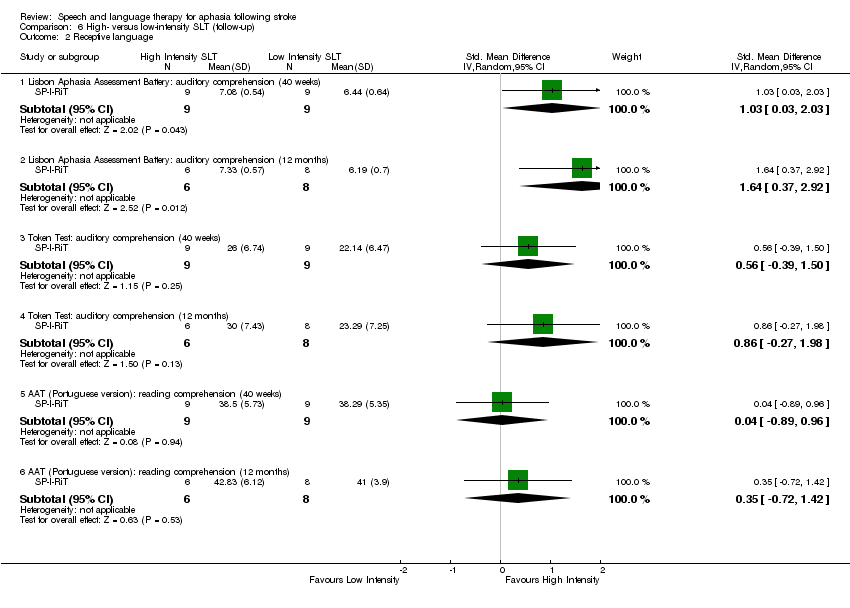

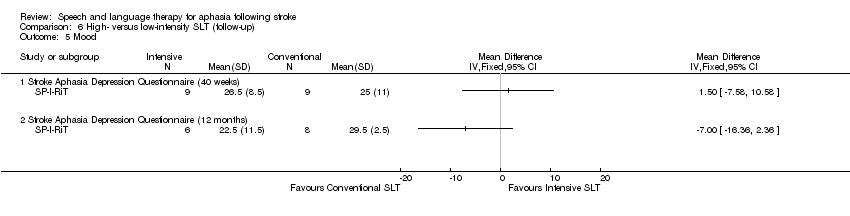

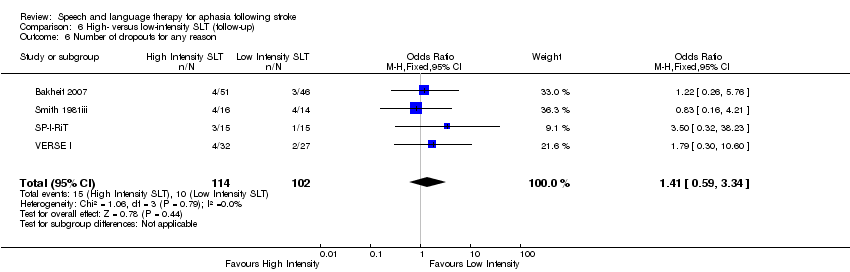

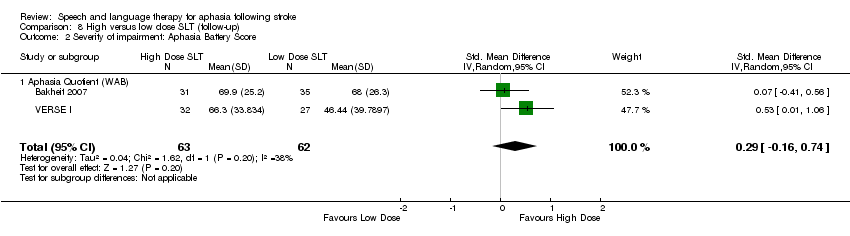

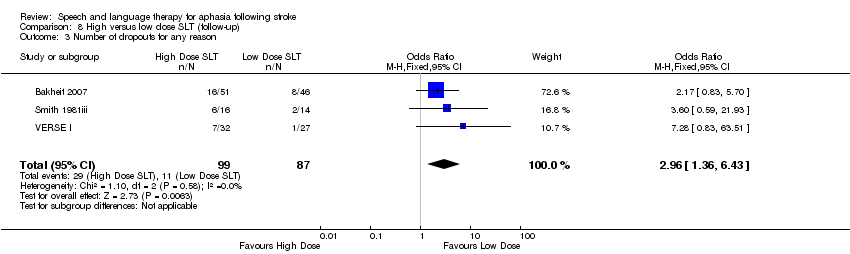

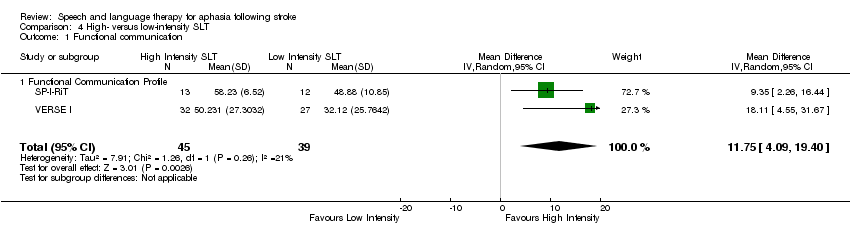

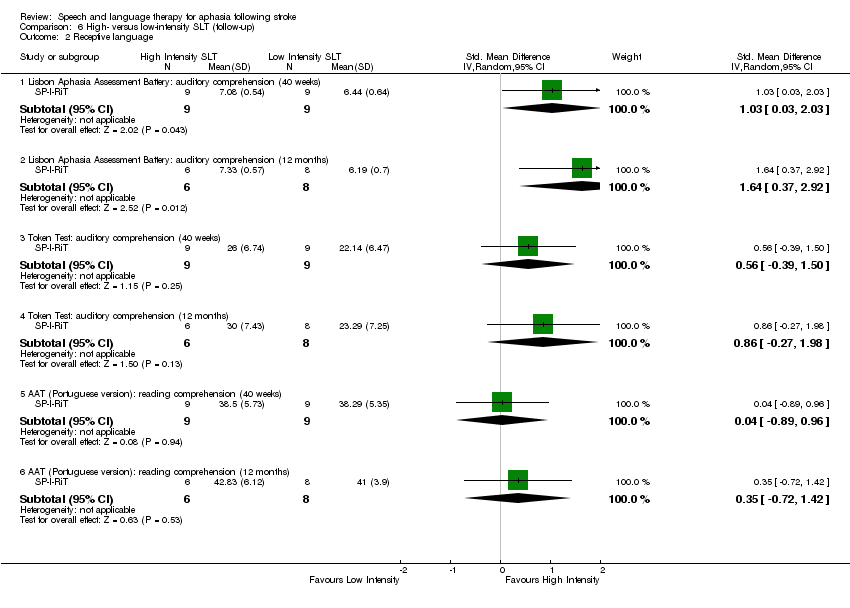

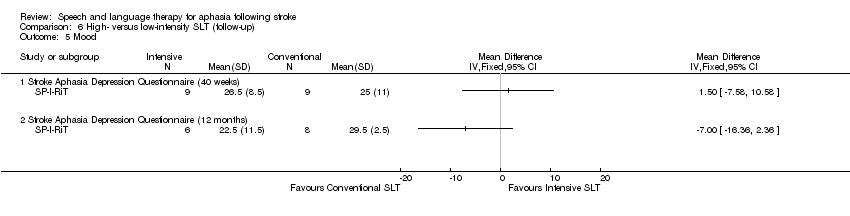

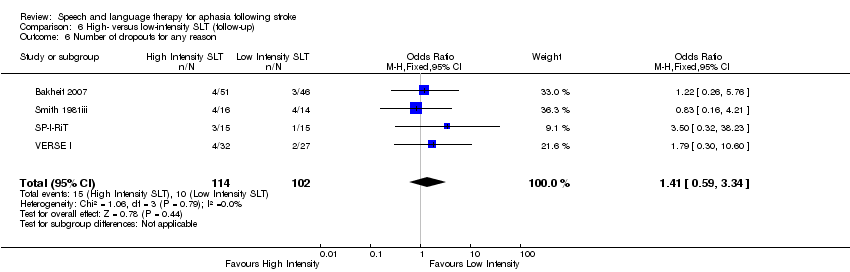

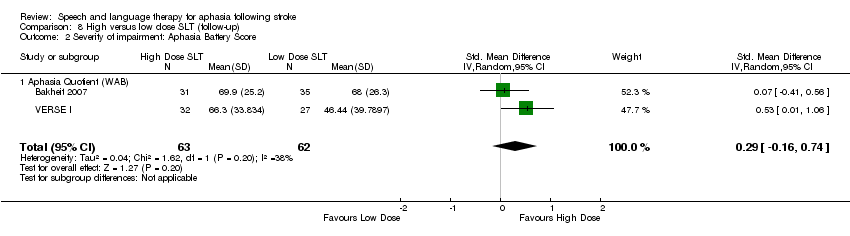

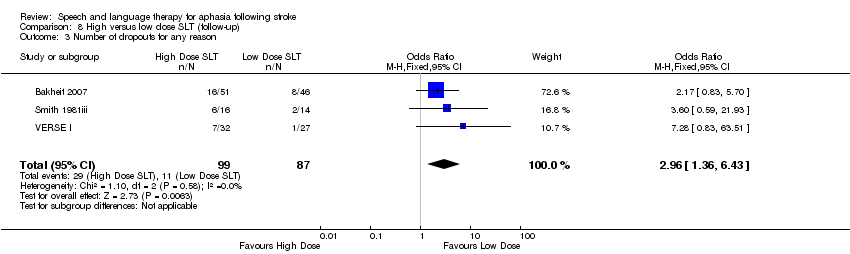

| Interventions | 1. High‐intensity SLT Intervention: high‐intensity SLT. Neuroplasticity enhanced via intensive behavioural treatment. Materials: picture‐object selection, object naming, communication aids and equipment. Procedures: picture‐object selection, object naming, recognition and associations; expression of feelings and opinions; conversational skills; gestural and non‐verbal communication (including communication aids and equipment). Provided by: speech and language therapists. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face; hospital rehabilitation unit, outpatient or home. Regimen: 1 h therapy, 5 sessions weekly for 12 weeks. Total dose = 60 h therapy. Tailoring: individualised. Modification: individualised. Adherence: yes. Method not reported. 2. Conventional SLT Intervention: SLT Materials: picture‐object selection, object naming, communication aids and equipment. Procedures: tasks included picture‐object selection, object naming, recognition and associations; expression of feelings and opinions; improving conversational skills; gestural and non‐verbal communication (including communication aids and equipment). Provided by: speech and language therapists. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face; hospital rehabilitation unit, outpatient or home. Regimen: 1 h therapy, 2 sessions weekly for 12 weeks. Total dose = 24 h therapy. Tailoring: individualised. Modification: individualised. Adherence: yes. Method not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: WAB Data collection: baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12 and 24 | |

| Notes | A further 'NHS group' was not randomised (first 6 consecutive participants allocated to this group) and were therefore excluded from this review Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random numbers table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequentially numbered sealed envelopes |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessors blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Authors reported that ITT analysis employed but not all participants appeared to be included in the final analyses |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Sample size calculation not reported Groups comparable at baseline Conventional group had 11 dropouts from the allocated intervention |

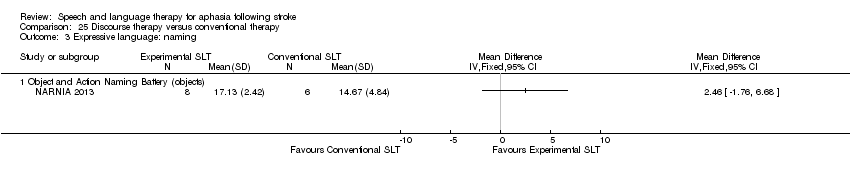

| Methods | Multicentre RCT stratified by severity of aphasia (mild/moderate/severe) and time poststroke (< 2 years/≥ 2 years), UK | |

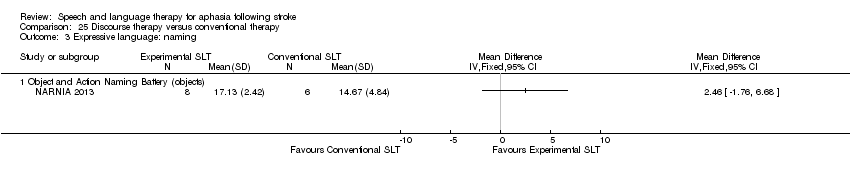

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of stroke and aphasia with word‐finding difficulties as 1 of the predominant features as assessed by the Object and Action Naming Battery and the Comprehensive Aphasia Test (Druks 2000; Swinburn 2004, respectively). Participants were included only if they had the ability to repeat spoken words presented by the recruiting speech and language therapist. Eligible participants no longer received impairment‐focused speech and language therapy enabling the computer treatment to be better isolated and evaluated. Participants with motor deficits poststroke were not excluded from the study. Where upper limb impairments made physical manipulation of the computer hardware difficult, assistive devices such as tracker balls or touchscreen computers were offered to enable access to the computer treatment Exclusion criteria: 3 people with severe visual or cognitive difficulties reducing ability to use the computer programme were excluded from the study, tested by the ability to see and perform a simple, nonlanguage‐based computer game Group 1: 16 participants Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Computer‐mediated word finding therapy Intervention: StepbyStep. Computer programmes developed for the treatment of aphasia provide exercises that can be carried out on a regular basis, targeting personal vocabulary and focusing on the patient's conversational needs. Such software has been reported to be useful in the provision of intensive independent language practice, giving rise to new opportunities to provide self management of continued aphasia treatment. There is growing evidence to suggest that the use of aphasia software can help to improve outcomes in language domains including reading, spelling, and expressive language. Materials: usual language activities (as described in no SLT arm). In addition, they received speech and language therapy intervention delivered through independent use of a computer therapy programme (StepbyStep) configured by a speech and language therapist and supported by a volunteer. A library of more than 13,000 language exercises. Photographic images can be added to enable practice of personally relevant words such as names of people and pets. The intervention group practiced Object and Action Naming battery words during the treatment (Druks 2000). In addition, participants in the intervention group practiced 48 words of personal relevance. Procedures: each exercise follows steps progressing from listening to target words, producing words with visual, semantic, phonemic, or written letter/word cues through to saying the words in sentences. Speech and language therapist also provided initial instruction to the participant and caregiver on how to use the computer exercises and progress through the therapy steps. Volunteers provided assistance in using the software and hardware, encouragement to practice, and activities to promote use of the new words in daily life. Provided by: speech and language therapist tailored the steps in the therapy process. Volunteers provided assistance in using the software and hardware, encouragement to practice, and activities to promote use of the new words in daily life. Volunteers contacted the participants once a week in the first month and at least once a month thereafter by telephone or home visit. Speech and language therapists trained. Volunteers included SLT students and existing volunteers from communication support groups. Volunteers were given a 3 h training session on how to use the StepbyStep programme and their role in supporting the intervention. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, computer facilitated. Speech and language therapist supported face‐to‐face, at home. Regimen: per protocol: 20 minutes 3 d a week for 5 months (approximately 1500 minutes of practice time in total). Volunteers contacted the participants once a week in the first month and at least once a month thereafter by telephone or home visit. Total dose = 25 h therapy. Tailoring: yes. Speech and language therapist tailored the steps in the therapy process as appropriate to the abilities and needs of the individual participant and provided initial instruction to the participant and caregiver on how to use the computer exercises and progress through the therapy steps.as appropriate to the abilities and needs of the individual. Modification: tailored choice of words and level of difficulty. Adherence: collected data via computer programme 2. No SLT Intervention: No formal SLT. Participation in everyday communication tasks and for some participants this may include attendance at communication support groups and conversation, reading, and writing activities that are part of everyday life.Materials: none. Procedures: none. Provided by: none (volunteers if attending local group) Delivery: not reported. Regimen: none. Tailoring: none. Modification: none. Adherence: not applicable | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: feasibility of carrying out the study design and using self managed computer treatment supported by volunteers as a long‐term intervention. Primary measures of feasibility were the recruitment rate, completion rates, and statistical variability. Outcomes indicating feasibility of the intervention included the percentage of the eligible population interested in receiving the intervention, the ability to offer the intervention per protocol (provision of computer software and volunteer support), and the ability of the participants to carry out the intervention per protocol (using the computer for at least 20 min 3 times a week for 5 months). Amount of practice time was stored by the StepbyStep computer software automatically and reviewed by a speech and language therapist at the end of treatment | |

| Notes | Dropouts are detailed in Table 2 Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Web‐based randomisation system. Stratified randomisation based on severity of aphasia (mild/moderate/severe) and time poststroke (< 2 years/ > 2 years) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Baseline assessments were conducted before randomisation, and assessment of outcomes undertaken blind to baseline and treatment allocation by blinded speech and language therapists |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Dropouts accounted for; ITT analysis employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Groups were comparable at baseline in terms of severity, sex, age, time postonset Pilot study so not possible to perform power calculation in advance but used data to calculate future sample size No other obvious bias |

| Methods | RCT, USA | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: 18 years of age or older, diagnosis of mild‐severe aphasia (1 or 2/3 on NIHSS), damage to left MCA area, first infarct, any dysarthria had to be less severe than their aphasia (as per NIHSS), able to follow commands, ability to sing at least 25% of Happy Birthday, demonstrate awareness of speech problems, English as their first language Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

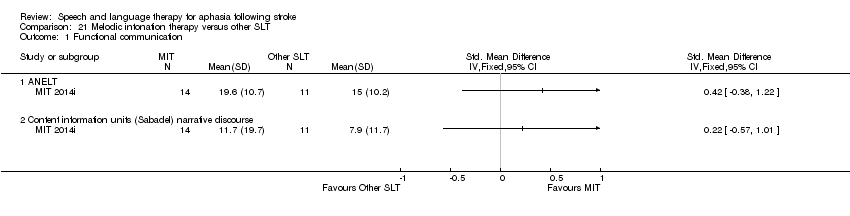

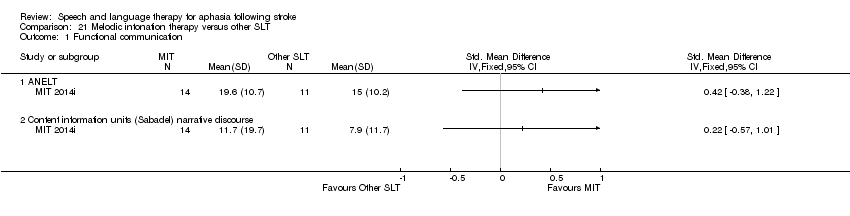

| Interventions | 1. Modified Melodic Intonation Therapy (MMIT) Intervention: MMIT. MIT has received positive reports. Modifications to original MIT approach include therapist composition and use of novel melodic phrases that match prosody of spoken phrases in pitch and rhythm, use of full phrases during initial treatment to facilitate access to intact areas of brain, and early introduction poststroke. Materials: not reported. Procedures: session 1: 10‐15 minutes MMIT. 1 phrase training. Therapist modelled phrase multiple times then asked participant to sing. Participant assisted by therapist to tap rhythm of phrase with their left hand to provide added cue. Subsequent sessions could add more phrases. Provided by: board‐certified music therapist trained in MMIT. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face, hospital. Regimen: protocol allowed for up to 5 sessions but not more than 3 delivered due to logistics and early discharge. Duration of individual sessions were 10‐15 mins (up to 45 min max). Tailoring: only in terms of progressive complexity/number of phrases. Modification: none. Adherence: no mention of any practice tasks. No mention of measures of adherence or fidelity. No report of all 5 sessions delivered as planned 2. No SLT Intervention: no SLT. Placebo control. Materials: none. Procedures: discussion on patient impairment, different forms of treatment, different outcomes, issues arising from aphasia. Provided by: board‐certified music therapist trained in MMIT. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face, location not reported. Regimen: single discussion, duration 10‐15 min. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: in‐trial developed assessment tool: repetition and responsiveness Secondary outcomes: Semantic Fluency Test, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, complex ideational subtest of the BDAE, Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test Data collection: baseline, 1 week prior to intervention, within 1 week of intervention. Follow‐up 3 months after intervention | |

| Notes | Dropouts are detailed in Table 2 Suitable statistical data permitting inclusion within the review meta‐analyses unavailable | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random numbers table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Adequate (allocated by music therapist after enrolment by nursing manager who had no prior knowledge of order of participants) |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Yes, 2 nurse managers |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Dropouts reported but reasons for withdrawal not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not all of the prespecified outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups comparable at baseline for age, days postonset, severity (measured by % Happy Birthday song) |

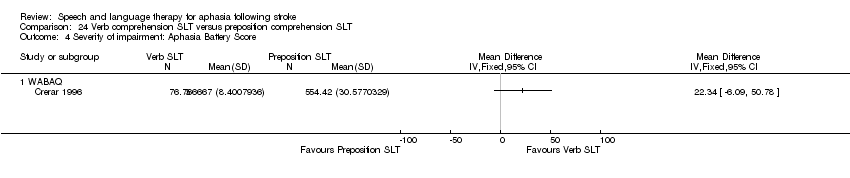

| Methods | Cross‐over RCT (only data prior to cross‐over treatment included in this review), UK | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: aphasia, problems with comprehension of written sentences, comprehension of small vocabulary of individual context words used in therapy, can recognise graphical representations of objects and actions in therapy sentences; right‐handed; could cope with computer interface Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Verb SLT Intervention: Verb SLT ‐ improved syntactic processing leading to improved sentence comprehension Materials: computer‐based remediation software. Procedures: protocolised tasks included picture building mode, picture creation to match written sentence, sentence building mode, sentence creation from available words to match a picture. Some flexibility between treatment modes and support provided by therapist. Provided by: computer programmer and SLT. Training and expertise not reported. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face; computer‐facilitated in clinical settings ("a quiet room, blinds and lighting adjusted for maximum screen clarity"). Regimen: 1 h therapy twice weekly for 3 weeks. Total dose = 6 h therapy. Tailoring: yes, based on testing profiles. Modification: not possible. Adherence: all participants retained up to (and following) cross‐over stage of RCT. 2. Preposition SLT Intervention: Preposition SLT. Materials: computer‐based remediation software. Procedures: protocolised tasks included picture building mode, picture creation to match written sentence, sentence building mode, sentence creation from available words to match a picture. Some flexibility between treatment modes and support provided by therapist. Provided by: computer programmer and speech and language therapist. Training and expertise not reported. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face; computer facilitated in clinical settings ("a quiet room, blinds and lighting adjusted for maximum screen clarity"). Regimen: 1 h therapy twice weekly for 3 weeks. Total dose = 6 h therapy. Tailoring: yes, based on testing profiles. Modification: not possible. Adherence: all participants retained up to (and following) cross‐over stage of RCT | |

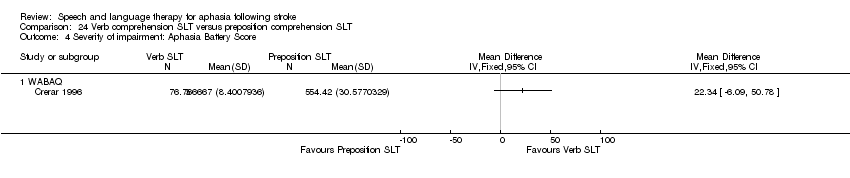

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: Real World Test ‐ verbs and prepositions (treated and untreated) Secondary outcomes: computer‐mediated assessment ‐ verbs and prepositions (treated and untreated) Morphology Data collection: baseline, post‐treatment 1 (cross‐over then baseline 2 and post‐treatment 2, which were not included in this review) | |

| Notes | Randomisation details provided through personal communication with authors Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Patient identification tags drawn from a hat |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Trialists drew patient identification tags drawn from a hat |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐based tests automatically recorded. Real World Tests were unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All participants retained up to (and following) cross‐over stage of RCT |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Sample size calculation not reported |

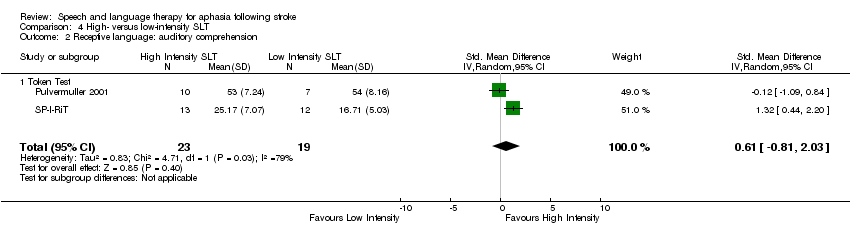

| Methods | RCT, USA | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: at least 6 months poststroke and had single or multiple lesions limited to the left hemisphere that included the precentral gyrus or underlying white matter as confirmed by medical records and MRI; standard score greater than 69.92 on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—IV (PPVT–IV; Dunn 2007); an ability to consistently follow one‐step commands; scores on the WAB–AQ below the aphasia cutoff of 93.8 (Kertesz 1982); (d) right‐handedness prior to the stroke, as determined by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield 1971); and (e) English as their first language. Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

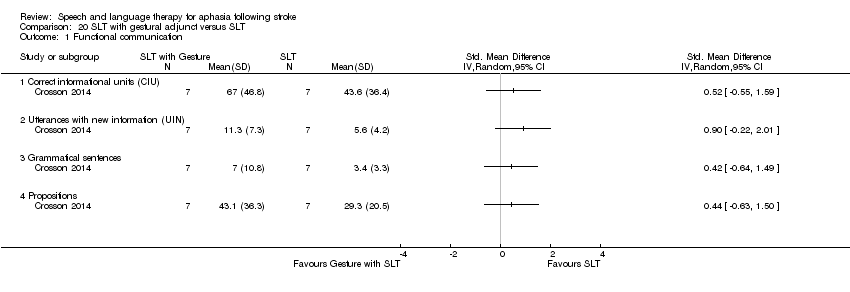

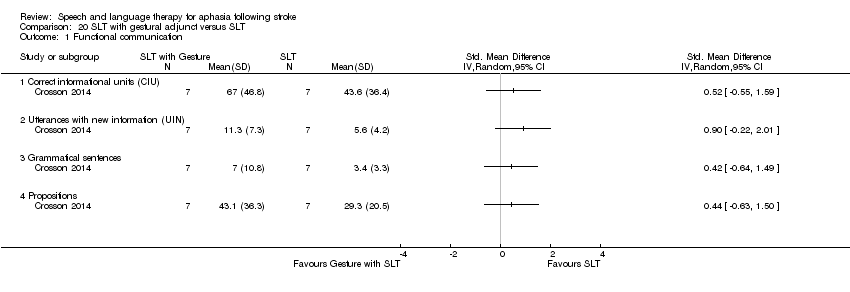

| Interventions | 1. Naming therapy with gesture Intervention: gesture SLT. Literature suggests the advantages of recruitment of right‐hemisphere mechanisms during language recovery in aphasia. Crosson 2007 devised an intention‐based treatment technique that engaged the right hemisphere by shifting intention and language production mechanisms to homologous right‐hemisphere regions. Crosson 2007 defined intention as the ability to select and initiate an action from many possible competing actions. Because the intentional circuits for volitional hand movement overlap, those for word generation in the pre‐supplementary motor area (pre‐SMA) preceding a naming attempt with a volitional complex left‐hand movement could facilitate picture naming. Materials: prior to treatment, all subjects named a set of more than 400 black‐and‐white line drawings of objects and generated members of 120 categories twice. Items missed consistently were selected for treatment, beginning with the highest frequency items and progressing to lower frequency items until enough items were identified to construct the counterbalanced treatment lists and probe stimuli. Specifically, from the set of 400 pictures and 120 categories, 120 pictures and 60 categories were individually selected for each subject, with the selected picture and category sets each containing 25% consistently correct and 75% consistently incorrect at pretreatment testing. Procedures: trained on both picture naming and category generation. Phase 1 consisted of treatment sessions 1–10 and focused on the naming of 50 pictures. Phase 2 consisted of treatment sessions 11–20 and trained subjects on the naming of 50 different pictures. Phase 3 consisted of treatment sessions 21–30 and required the generation of an exemplar of each of 40 different categories. Naming trials in Phases 1 and 2 consisted of the presentation of a picture on a computer monitor for naming. In Phase 3, trials consisted of auditory and orthographic presentations of a category name for which the subject generated 1 category member. For all trials in all phases, a therapist verified response accuracy. If treatment trials were completed correctly (i.e., a picture was named correctly or a correct category exemplar was generated), subjects began the next trial. If an item was not named correctly, the therapist would provide the correct name, and subjects would then practice saying the correct response. Similarly, if a subject was unable to generate a member of a category, the therapist would provide an example, and the subject would practice saying this correct response. This correction procedure was repeated up to 3 times maximum or until the subject named the item correctly. The number of times a subject repeated the correct response was not regulated. Each member of the gesture group initiated each treatment trial with his or her left hand by opening and reaching into a box and pushing a red button. Second, during each correction procedure, each member of the gesture group also made a non‐meaningful circular gesture with his or her left hand. Provided by: speech and language therapists. The same therapists administered both the gesture and the no gesture treatments. Training not reported. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face and computer, location not reported. Regimen: treatment was delivered in 3 phases (10 sessions per phase), with two 1 h treatment sessions per day, 5 d a week, for a total of 30 treatment sessions. The 2 sessions each day were at least half an hour apart. Total dose = 30 h therapy. Tailoring: yes, naming targets by successful/unsuccessful attempts on baseline measure. During therapy correction and prompt and advancement through levels based on patient ability. Modification: not reported.Adherence: therapist monitored patient's protocol adherence. For treatment sessions a research assistant—who was trained in both treatments and who was not administering treatment at any of the sites—evaluated 1 session per treatment phase (i.e., once a week) per subject for correct delivery of the assigned treatment and subsequent correction procedures. 2. SLT Intervention: SLT. Usual care. Materials: described above. Procedures: trained on both picture naming and category generation. Phase 1 to Phase 3 treatment sessions described above. For all trials in all phases, a therapist verified response accuracy, as described above. For the no gesture group, a therapist pushed a button to initiate each treatment trial. No hand movement was required by the participant during the correction procedure. Provided by: speech and language therapists. The same therapists administered both the gesture and the no gesture treatments. Training not reported. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face and computer, location not reported. Regimen: treatment was delivered in 3 phases (10 sessions per phase), with two 1 h treatment sessions per day, 5 d a week, for a total of 30 treatment sessions. The 2 sessions each day were at least half an hour apart. Total dose = 30 h therapy. Tailoring: yes, naming targets by successful/unsuccessful attempts on baseline measure. During therapy correction and prompt and advancement through levels based on patient ability. Modification: not reported. Adherence: therapist monitored patient's protocol adherence. For treatment sessions a research assistant—who was trained in both treatments and who was not administering treatment at any of the sites—evaluated 1 session per treatment phase (i.e., once a week) per subject for correct delivery of the assigned treatment and subsequent correction procedures. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: the naming of pictures from the BNT, WABAQ, and discourse production (various ‐ number of nouns; verbs; total number of words; correct information units (Nicholas 1993); utterances with new information (Del Toro 2008); propositional analysis of narrative discourse; Grammaticality. Discourse tasks: describing Norman Rockwell pictures and answering open‐ended questions. Data collection: baseline, post‐treatment. Follow‐up at 3 months | |

| Notes | Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. Stratified random sampling to equalise groups on picture‐naming ability using BNT scores. Groups were also matched on the number of subjects whose lesions extended anteriorly beyond the precentral sulcus |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No power calculation Groups were comparable at baseline for age, education, aphasia severity, naming severity |

| Methods | Parallel group RCT, UK | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: aphasia, less than 85% on FCP (x 2), English speaking, at least 3 weeks after stroke Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

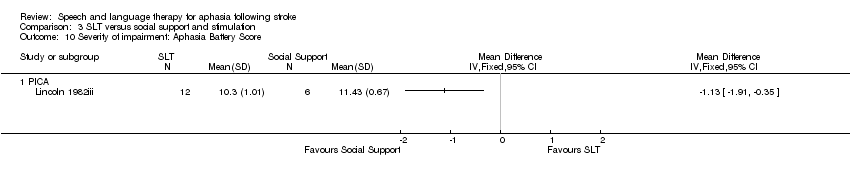

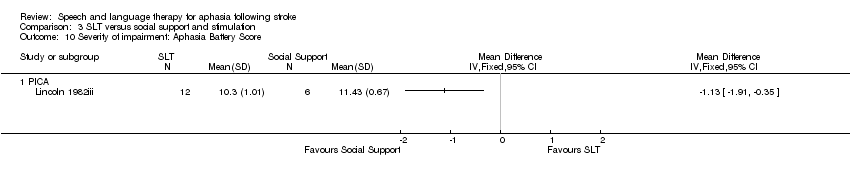

| Interventions | 1. Conventional SLT Intervention: usual care SLT Materials: usual care Procedures: as deemed appropriate by SLT. Provided by: qualified therapist. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face; not reported where the intervention was delivered. Regimen: up to 2 h therapy weekly for 15 to 20 weeks. Total dose = 30 h therapy. Duration of individual not reported. Tailoring: individualised. Modification: not reported. Adherence: dropout rate recorded. 2. Social support and stimulation Intervention: "Unfamiliar volunteers". General stimulation and social support. Materials: not reported. Procedures: volunteers provided with details about participant's aphasia, general support and within‐treatment assessment scores and instructed to 'encourage' communication but no instruction in SLT techniques Provided by: volunteers. Training not specified but required to be reliable and able to provide 2 h per week to patient. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face, SLT department. Regimen: up to 2 h support weekly up to 15 to 20 weeks. Total dose = 30 h contact time. Tailoring: individualised. Modification: not reported. Adherence: dropout rate recorded | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: FCP, Schuell Assessment | |

| Notes | Randomisation details provided through personal communication with authors of original review Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random numbers table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessor not treating therapist |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | ITT analysis not employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Sample size calculation not reported |

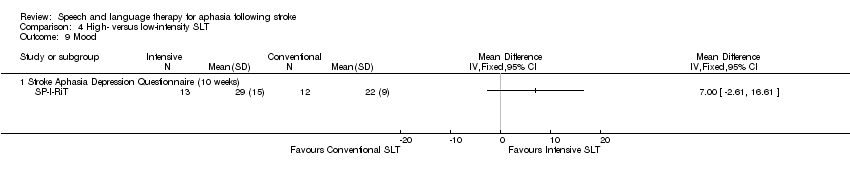

| Methods | Parallel group RCT, Italy | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: global aphasia, left CVA, within first year after stroke, right‐handed, native Italian speakers, literate Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. High‐intensity SLT Intervention: "Intensive SLT". Intensity is important. Cost‐benefit ratio questionable. Materials: not reported. Procedures: conversational approach more focused on comprehension (e.g. picture‐matching to understanding complex scenes, short stories, engaging patient in conversation, retelling personally relevant stories). Ecological approach based on conversation, comprehension (mostly) and production deficits. Little focus on reading/writing other than in support of the production and comprehension. Provided by: qualified therapists. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face; mostly outpatient. Regimen (frequency (sessions weekly) x duration): 45‐60 min therapy sessions approximately 5 times weekly for 6 months. Dose = estimated 96.75 to 129 h therapy Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: method not reported 2. Conventional SLT Intervention: standard SLT. Materials: not reported. Procedures: based on stimulation approach. Provided by: speech and language therapists. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face; mostly outpatient. Regimen : 45‐ 60 min therapy session approximately 3 times weekly for 6 months. Total dose = 78 h therapy. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: method not reported | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: AAT | |

| Notes | Data from an additional 4 non‐randomised participants with global aphasia were also reported. They received no SLT intervention but were assessed at 6‐month intervals, and their scores were used to account for spontaneous recovery. They were not included in this review. Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessors blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All randomised participants included in analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Sample size calculation not reported |

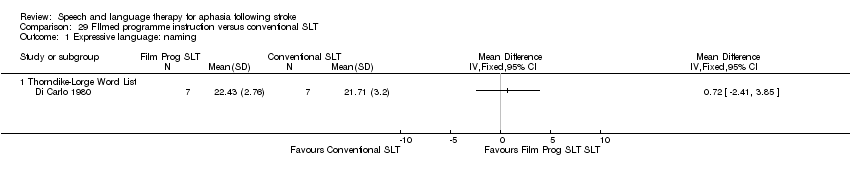

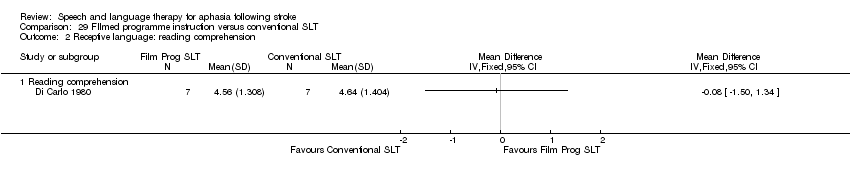

| Methods | Parallel group RCT, USA | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: right‐handed, left MCA stroke Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

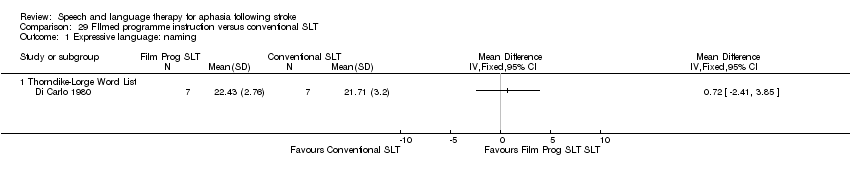

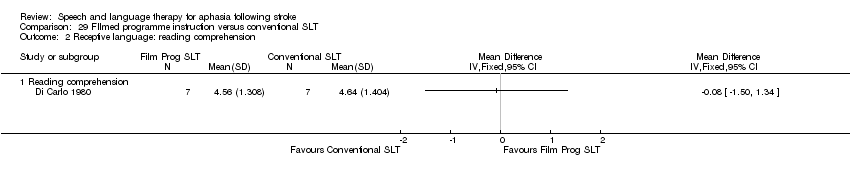

| Interventions | 1. Conventional SLT with filmed programmed instruction Intervention: "Conventional SLT with filmed programmed instruction". "New methods . . . minimise stress and frustration and reduce instruction time" "programmed instruction . . . based on modern learning theory". Developed on modern linguistic learning principles and theory (for people who were hearing impaired). Materials: 30 language training films, preceded by 10 perceptual and 5 thinking films for practice. Procedures: "Filmed programmed instruction": perceptual, thinking and language training films (designed for population with hearing impairment) based on linguistic learning theory; passing criterion of 80%, then progression to the next film. Provided by: not reported Delivery: not reported Regimen: not reported but at least 80 h for 5‐22 months. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported. 2. Conventional SLT Intervention: "Conventional SLT and non‐programmed activity". Rationale not reported. Materials: not reported. Procedures: "traditional" therapy and viewing slides, bibliotherapy and "other non‐programmed" activity. Provided by: not reported Delivery: not reported Regimen: not reported ‐ at least 80 h for 6‐ 9 months. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: reading recognition, reading comprehension, visual closure, visual learning, vocabulary learning | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Unclear risk | Outcome assessor blinding not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All randomised participants included in analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Sample size calculation not reported |

| Methods | RCT, Netherlands | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: age 20‐86 years, native Dutch speaker, minimum 11 months after stroke with moderate‐to‐severe naming deficits Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Computer‐mediated SLT Intervention: "multicue". Person with aphasia experiences impact of various cue types on their naming abilities. Permits internalisation and development of self cueing strategies. Materials: written cues and written feedback. Procedures: 4 series of 80 pictures randomly presented. High and low frequency of words of varying length (1‐4 syllables). Coloured picture of word. If word cannot be produced then cues are employed from choice of semantic, orthographic, sentence completion, distraction/take break. First 4 sessions: therapist follows protocol to support patient. Cues introduced sequentially over first 4 sessions. Written responses. Session 5 onwards: therapist withdraws but continues to check progress. Provided by: therapist. Training not reported. Delivery: computer‐based; 1‐to‐1; location not reported. Regimen: 30‐45 minutes therapy over 2‐3 sessions weekly for 2 months. Total dose = 10‐11 h therapy. Tailoring: cues could be reduced or omitted according to patient need. Regular therapist review on progress and problem items. Modification: none reported. Adherence: not reported. 2. No SLT Intervention: no SLT Materials: none Procedures: none. Delivery: none. Regimen: none Modification: none. Adherence: not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: BNT, ANELT‐A Data collection: assessed at baseline and end of treatment | |

| Notes | Co‐intervention: psychosocial group therapy aimed at coping with consequences of aphasia, not reported if all participated Dropouts are detailed in Table 2 Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated sequence |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Concealment in sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Trialists were the outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | ITT analysis not employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | A priori sample size calculated |

| Methods | Parallel group RCT, USA | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: none listed Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Task‐specific SLT gestural Intervention: AMERIND Gestural Code Cueing. Responses to intersystematic tasks may be enhanced via visual cue for a verbal response. Sessions designed to drill word‐retrieval skills, using cueing where necessary. Materials: 30 common nouns controlled for word frequency and picturability. Procedures: picture naming. Plus 2 pre‐therapy training sessions (20 minutes each). Also had AMERIND cues in addition to the traditional initially‐syllable and sentence ‐completion cues. Presentation of cue type randomised for each session. Provided by: not reported. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, residential aphasia programme at university. Regimen (frequency (sessions weekly) x duration): 15‐30 minutes daily for 2 weeks. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported. 2. Conventional SLT Intervention: Auditory‐verbal cueing. Initial syllable and sentence‐completion cues are more facilitatory than other cues. Drilling word‐retrieval skills using cueing when necessary. Materials: 30 common nouns controlled for word frequency and picturability. Procedures: received traditional initial‐syllable and sentence completion cues. Standardised cueing protocol for sentence completion published as appendix to paper. Provided by: not reported. Delivery: 1‐to‐1; residential aphasia programme at University. Regimen 15‐30 minutes daily for 2 weeks. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: picture naming test (20/30 items from the Aphasia Therapy Kit) (Taylor 1959), response times | |

| Notes | Suitable statistical data permitting inclusion within the review meta‐analyses unavailable | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All randomised participants included in analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All prespecified outcomes reported. However although they reported mean values for % correct responses, SD were not reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Inclusion criteria not listed |

| Methods | Cross‐over group RCT (only data collected prior to cross‐over treatment included in this review), USA | |

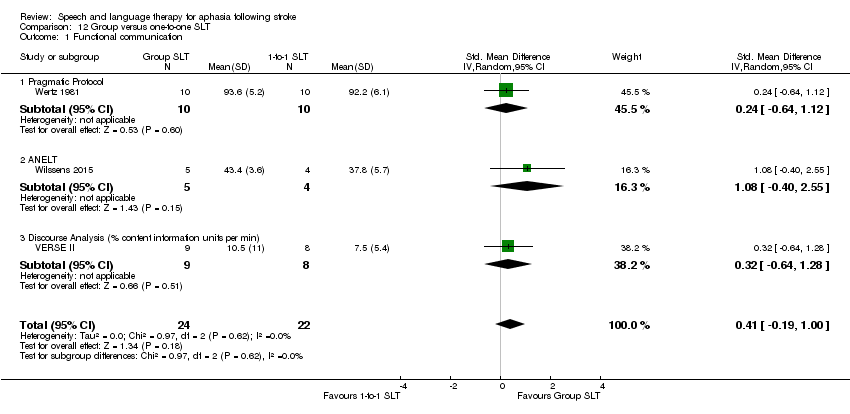

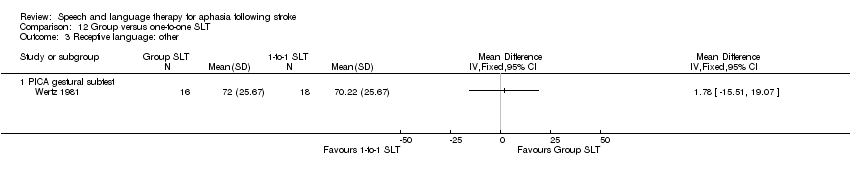

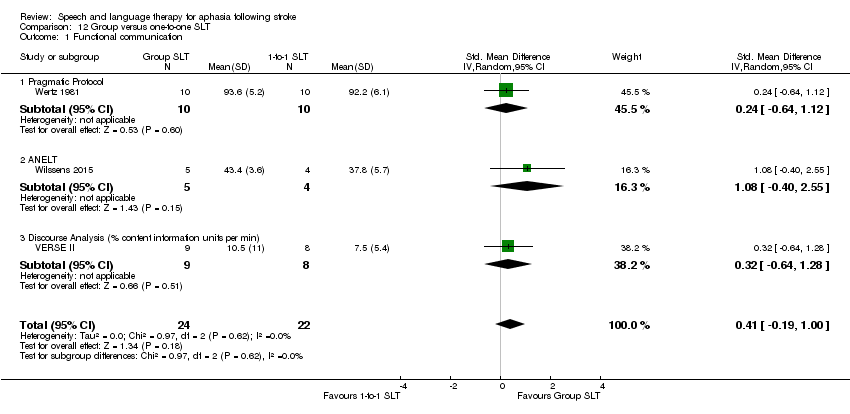

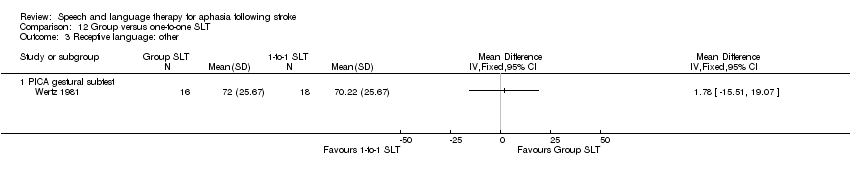

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: > 6 months after stroke, completed SLT available via insurance, single left hemisphere stroke, 80 years or younger, premorbidly literate in English, no medical complications or history of alcoholism, 10th to 90th overall percentile on SPICA on entry, attend more than 80% of therapy Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Group SLT Intervention: SLT. Group therapy approaches effective as they facilitate generalisation, improve psychosocial functioning and participation, and are cost‐effective. Materials: communication of message using any verbal/non‐verbal methods in group format. Fostering initiation of conversation, expanding aphasia understanding, awareness of personal goals, recognition of progress made, promoting confidence. Communication facilitated by communicative drawing, roleplay, natural gestures, resources (e.g. maps) props, personal notebooks, number lines, conversational prompting, graphic choices, scripting. Reading and writing tasks. Social games for communication practice. Procedures: opening 90 min: discussion current activities and events. speech and language therapist‐facilitated discussion of topics relevant to group. Sharing of facilitator's role amongst group. Encourging peer feedback, cueing and peer volunteers. Some reading and writing tasks. Social games. Performance artist (1 h weekly) to facilitate physical exercises, creative expression. Provided by: speech and language therapist plus family or artist. Delivery: group, face‐to‐face; not reported (possibly Aphasia Centre). Regimen: 2.5 h session twice weekly for 4 months. Total dose = up to 160 h therapy. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: 80% attendance. 2. Social support and stimulation Intervention: social group activities and classes. Social contact control, provide opportunity for socialisation. Materials: not reported. Procedures: activities varied depending on social activities of their choice but included movement classes, creative/performance arts groups, church activities, support groups. Provided by: not reported. Delivery: group, face‐to‐face; location not reported. Regimen: at least 3 h weekly for 4 months. Total dose = 52 h contact. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: Shortened Porch Index of Communicative Ability, WABAQ, Communicative Activities in Daily Living | |

| Notes | Dropouts: 7 participants (conventional SLT 3; social support and stimulation 4). Dropouts are detailed in Table 2 Suitable statistical data permitting inclusion within the review meta‐analyses unavailable | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | High risk | Outcome assessor inadequately blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | ITT analysis not employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Not all prespecified outcomes were reported. CETI, Affect Balance Scale and connected speech measures data and "conversations about videotaped television segments" were not reported in the paper. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups comparable at baseline (age, education level, aphasia severity) |

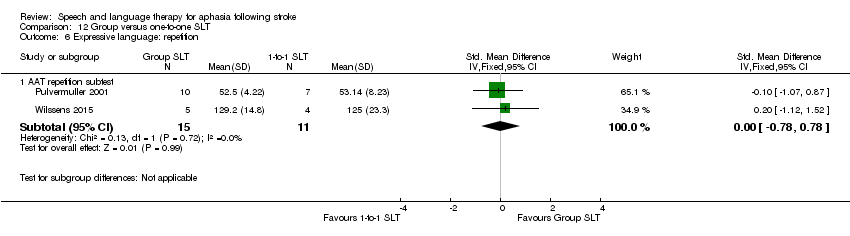

| Methods | RCT, Germany | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: left hemisphere cerebrovascular accident less than 3 months prior; aphasia (as per clinical diagnosis and screening test); monolingual German speaker Exclusion criteria: aphasia primarily automatisms; severe jargon; severe apraxia of speech; severe neuropsychological disorders, psychiatric disorders or both Group 1: 13 participants Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

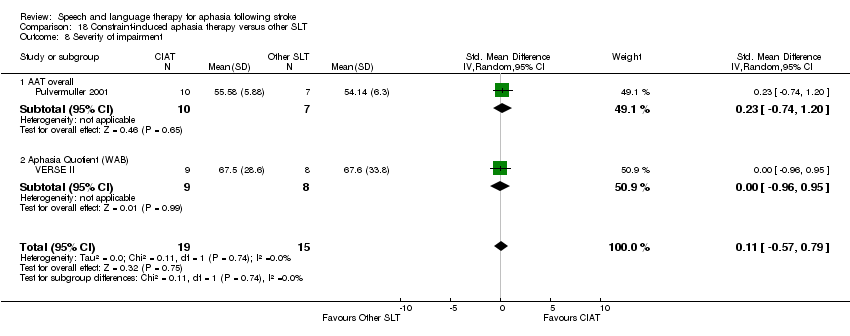

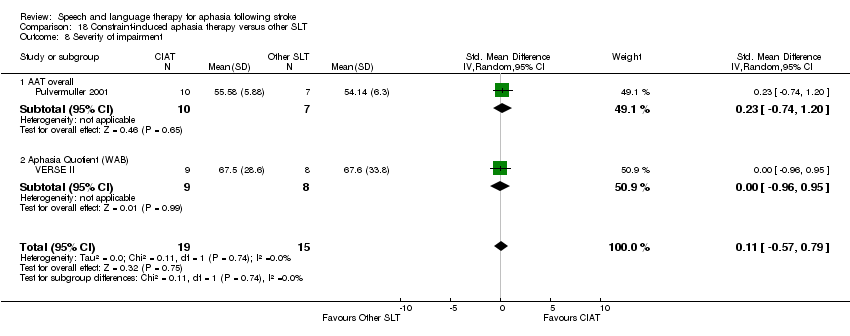

| Interventions | 1. CIAT Intervention: forced‐use aphasia therapy. Materials: not reported.Procedures: "therapy focused on communicative aspects". Provided by: not reported. Delivery: face‐to‐face, group, location not reported. Regimen: 5 sessions/week, each session 3 h duration, delivered over 6 week period. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported. 2. Conventional therapy Intervention Materials: not reported.Procedures: conventional therapy focused on language/linguistic skills. Provided by: not reported.Delivery: face‐to‐face, group, location not reported. Regimen: 5 sessions/week, each session 45 minutes duration, delivered over 6 week interval. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: AAT, Aphasia Checklist Data collection: baseline and immediately postintervention (6 weeks) | |

| Notes | Suitable statistical data permitting inclusion within the review meta‐analyses unavailable | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Not all participants accounted for at follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Lack of any statistical data analysis reported for outcomes |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not reported whether groups were comparable at baseline |

| Methods | RCT, USA | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: single left hemisphere stroke, native English speaker, minimum 3 months after stroke, hearing and vision corrected to normal, minimum high school education, chronic non‐fluent aphasia Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

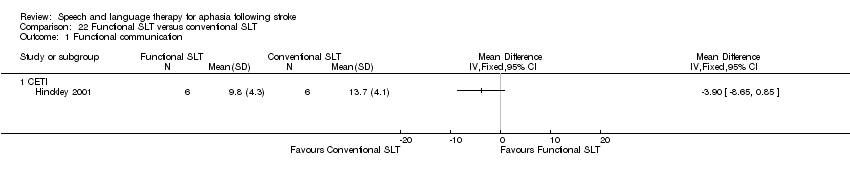

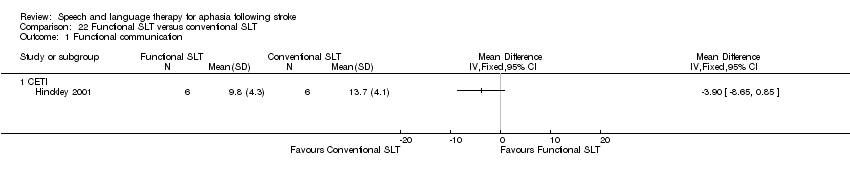

| Interventions | 1. Functional SLT Intervention: functional SLT. Disability‐based, context‐trained. Activity based, personal relevance emphasised. Establish compensatory strategies based on clients strengths to achieve targeted task. Materials: roleplay scripts, various actual catalogues, practice order forms, phone, credit cars, pen/paper, cue cards as individualised for each client. Procedures: roleplays of functional tasks, establish compensatory strategies (practice ordering by telephone, self generate individualised strategies). Use different strategies and modalities to achieve goal/task. Provided by: speech and language therapist trained in both treatment approaches. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face, location not reported. Regimen: 20 h weekly for 5 weeks. Total dose = 100 h of therapy. Tailoring: materials individualised. Modification: materials individualised. Adherence: reviewed for adherence to allocated intervention. 2. Conventional SLT Intervention: "Impairment‐based therapy". Deficit/impairment based therapy approach. Materials: stimulus items from targeted vocabulary that combine both picture and written words. Pictured stimuli for auditory comprehension tasks. Procedures: impairment‐based, skill trained, remediating naming deficit areas using cueing hierarchies using various modalities. Centred on targeted dimensions of performance (e.g. accuracy, speed or response, nature of required cueing). Provided by: speech and language therapists trained in both treatment approaches. Delivery: 1‐to‐1, face‐to‐face, location not reported. Regimen: 20 h weekly over 5 weeks. Total dose = 100 h therapy. Tailoring: none. Modification: none. Adherence: reviewed for adherence to allocated intervention. | |

| Outcomes | CADL‐2, CETI (completed by primary caregiver), phone and written functional task developed for project (catalogue ordering quiet and tone), PALPA oral and written picture naming | |

| Notes | 5 additional participants were non‐randomly assigned to a baseline group (both functional SLT and conventional SLT), but they were excluded from this review Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Unclear risk | Outcome assessor not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All randomised participants included in analyses |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups comparable at baseline (age, time postonset, aphasia severity, education, occupation) |

| Methods | RCT, USA | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: single left hemisphere stroke, maximum 85 years, minimum 1 year after stroke, PICA overall between 15th to 90th percentile, premorbidly right‐handed, minimum education 8th grade, premorbidly literate in English, vision no worse than 20/100 corrected in better eye, hearing no worse than 40 dB unaided in better ear, no language treatment 3 months before entry to study, non‐institutionalised living environment Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Computer‐mediated SLT Intervention: "computer reading treatment software". Treatment of reading and writing skills using computers. Isolated practice possible. Minimal responses required. Schuell's stimulation approach. Targeting maximised interaction within challenging tasks. Materials: 32 activities, 232 sequentially arranged visual matching and reading activities from 2‐5 choices. Text characters (letters, numbers, symbols). No pictures. Stimulus in centre of top third of screen. Response choices simultaneously displayed bottom half of screen. Tasks sequential in hierarchy of difficulty. 10 matching activities, 22 reading comprehension tasks with 8 difficulty levels. 4 comprehension tasks had 2 difficulty levels. Matching activities were perceptual visual matching to familiarise patient with software. Reading comprehension stimuli (letters numbers, words, phrases and sentences). Procedures: visual matching and reading comprehension tasks. Speech and language therapist familiarised patient with computer, programme and tasks. Demonstrated response modes. Provided by: 4 therapists but minimal involvement. Supportive functions but not in room. Delivery: computer‐facilitated; 1‐to‐1; SLT dept (2 occasionally at home with support; not clear which group). Regimen (frequency (sessions weekly) x duration): 3 h weekly for 26 weeks. Total dose = 78 h therapy. Tailoring: 4 participants needed additional cues during 1 or more sessions. Each task had a baseline set of 20 tasks. If criterion performance of 80% correct in 3 consecutive baseline tasks then programme proceeded to next task. Typically, movement up and down training hierarchy was controlled automatically by the programme. Modification: each task had a baseline set of 20 tasks. If criterion performance of 80% correct in 3 consecutive baseline tasks then programme proceeded to next task. If criterion performance not reached on baseline then therapist used Editor option to divide baseline 20 items into 2 sets of 10 items. Adherence: therapist monitored attendance and performance. Overall report ‐ participants completed mean of 76.14 tasks (range 1‐167) after computerised treatment. 19 or 21 participants completed at least 40 tasks. 2. No SLT Intervention: no SLT Materials: none. Procedures: none. Delivery: none. Regimen: none Modification: none. Adherence: not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: PICA, WABAQ | |

| Notes | Dropouts: 6 participants (computer‐mediated SLT 0, no SLT 6). Dropouts are detailed in Table 2 Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random numbers table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Outcomes measured by 1 of 4 speech and language therapists, 95% checked by second speech and language therapist with no knowledge of group allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Dropouts accounted for but ITT analysis not employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups were comparable at baseline |

| Methods | Parallel group RCT, USA | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: single left hemisphere stroke, maximum 85 years, minimum 1 year after stroke, PICA overall between 15th to 90th percentile, premorbidly right‐handed, minimum education 8th grade, premorbidly literate in English, vision no worse than 20/100 corrected, hearing no worse than 40 dB unaided, no language treatment 3 months before entry to study, non‐institutionalised living environment Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Computer‐mediated SLT Intervention: "computer reading treatment software". Treatment of reading and writing skills using computers. Isolated practice possible. Minimal responses required. Schuell's stimulation approach. Targeting maximised interaction within challenging tasks. Materials: 32 activities, 232 sequentially arranged visual matching and reading activities from 2‐5 choices. Text characters (letters, numbers, symbols). No pictures. Stimulus in centre of top third of screen. Response choices simultaneously displayed bottom half of screen. Tasks sequential in hierarchy of difficulty. 10 matching activities, 22 reading comprehension tasks with 8 difficulty levels. 4 comprehension tasks had 2 difficulty levels. Matching activities were perceptual visual matching to familiarise patient with software. Reading comprehension stimuli (letters numbers, words, phrases and sentences). Procedures: visual matching and reading comprehension tasks. Speech and language therapist familiarised patient with computer, programme and tasks. Demonstrated response modes. Provided by: 4 therapists but minimal involvement. Supportive functions but not in room. Delivery: computer‐facilitated; 1‐to‐1; SLT dept (2 occasionally at home with support; not clear which group). Regimen (frequency (sessions weekly) x duration): 3 h weekly for 26 weeks. Total dose = 78 h therapy. Tailoring: 4 participants needed additional cues during 1 or more sessions. Each task had a baseline set of 20 tasks. If criterion performance of 80% correct in 3 consecutive baseline tasks then programme proceeded to next task. Typically, movement up and down training hierarchy was controlled automatically by the programme. Modification: each task had a baseline set of 20 tasks. If criterion performance of 80% correct in 3 consecutive baseline tasks then programme proceeded to next task. If criterion performance not reached on baseline then therapist used Editor option to divide baseline 20 items into 2 sets of 10 items. Adherence: therapist monitored attendance and performance. Overall report ‐ participants completed mean of 76.14 tasks (range 1‐167) after computerised treatment. 19 or 21 participants completed at least 40 tasks. 2. Computer‐based cognitive tasks Intervention: computer‐based placebo: computerised cognitive rehabilitation software and arcade‐style games, no language stimulation. Attention control. Materials: animation, shape or colour to focus on reaction time, attention span, memory and other skills that did not overtly require language or other communication abilities. Games were commercially available. Used joystick. Games were golf, puzzles may have had some level of language processing (labelling or planning) but unstructured and incidental. Procedures: commercially available arcade‐style products. Provided by: 4 therapists but minimal involvement. Supportive functions but not in room. Delivery: computer‐based; 1‐to‐1; SLT clinic (2 occasionally at home with support not clear which group). Regimen: 3 h weekly for 26 weeks Tailoring: not reportedModification: not reportedAdherence: therapist monitored attendance and performance. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: PICA, WABAQ | |

| Notes | Dropouts: 2 participants (computer‐mediated SLT 0; no SLT/computer‐based placebo 2). Dropouts are detailed in Table 2 Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random numbers table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Outcomes measured by 1 of 4 speech and language therapists, 95% checked by 2nd speech and language therapist with no knowledge of group allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Dropouts accounted for but ITT analysis not used |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups were comparable at baseline |

| Methods | Parallel group RCT (stratified according to NIHSS result), Sweden | |

| Participants | Consecutive admissions to stroke unit Group 1: 62 participants Group 2: 61 participants Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. SLT (Language Enrichment Therapy) Intervention: "Early Intensive Language Enrichment (Comp) Therapy" (Salonen 1980). Commonly used clinically in Sweden. Mainly comprehension exercises, some naming hierarchy. Materials: pictures divided into 8 sections (in hierarchical difficulty): familiar phrases, compound words, basic sentences, basic words, additional words, descriptive words, standard sentences, and sentences. Procedures: protocol. Provided by: 5 specially trained therapists Delivery: face‐to‐face; 1‐to‐1; location not reported. Regimen: 45 minutes therapy 5 d weekly for 3 weeks. Total dose = 11.25 h (per protocol a minimum of 600 minutes) therapy. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: recorded deviations from per protocol intervention of minimum 600 min of SLT. SLT per protocol 54/59 randomised; no SLT per protocol 51/56 randomised. 2. No SLT Intervention: no SLT Materials: none Procedures: none. Delivery: none over 3 weeks. Could start SLT after 21 d. Regimen: none Modification: none. Adherence: not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: ANELT (at day 16) Secondary outcome: NGA (at day 16) | |

| Notes | Funded by the Stockholm County Council Foundation (Expo‐95), Karolinska Institutet, Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation and AFA Insurances Dropouts: 8 participants (1 died, 4 severely ill, 3 declined) Statistical data included within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Centrally randomised by independent statistician |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Consecutively sealed envelopes (opaque not specified) |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | 3 therapists blinded to treatment allocation; a fourth also rated recordings blinded to treatment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | ITT analysis employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | SLT had a more frequent history of myocardial infarction than the non‐SLT group |

| Methods | Parallel group RCT (stratified by aphasia type), Portugal | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: no history of neurological or psychiatric disease, first left stroke (single), first month after stroke, moderate‐severe aphasia, good health, maximum 70 years, residing near hospital with flexible transport Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

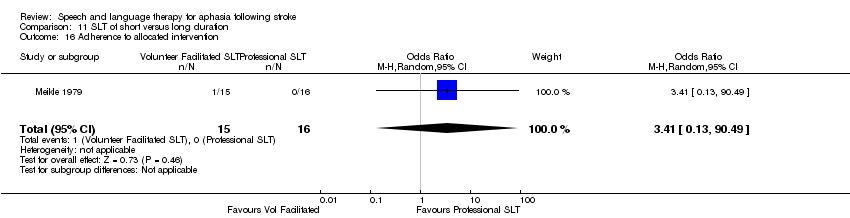

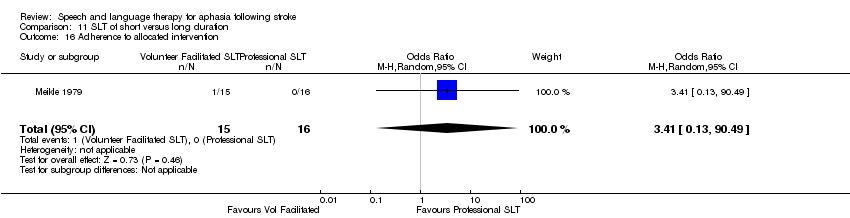

| Interventions | 1. Volunteer‐facilitated SLT Intervention: "volunteer facilitated therapy". Rationale not reported. Materials: speech and language therapist provided relatives with information and working material. Procedures: relatives encouraged to stimulate patient as much as possible. Provided by: relatives and volunteers. Therapists provided relatives with information and working material. Delivery: face‐to‐face; 1‐to‐1; home. Regimen (frequency (sessions weekly) x duration): "as much as possible" over 6 months. Total dose of therapy delivered over the intervention not reported. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported what it focused on, but relatives monitored monthly by therapist. Dropout rate recorded. 2. Conventional SLT Intervention: "conventional janguage sessions from a speech therapist". Effectiveness of SLT. Materials: not reported. Procedures: not reported. Provided by: therapist (training not reported). Delivery: 1‐to‐1; Face‐to‐face; out patient clinic. Regimen: 1 h therapy 3 sessions weekly for 6 months. Total dose = 78 h therapy. Tailoring: not reported. Modification: not reported. Adherence: not reported. | |

| Outcomes | Test Battery for Aphasia created by trialists (reported to have good correlation with WAB) | |

| Notes | Dropouts: 34 participants (conventional SLT 21; volunteer‐facilitated SLT 13). Dropouts are detailed in Table 2 Statistical data reported in a manner unsuitable for inclusion within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessor not therapist |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | ITT analysis not employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information available |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Groups were comparable at baseline. Sample size calculation not reported |

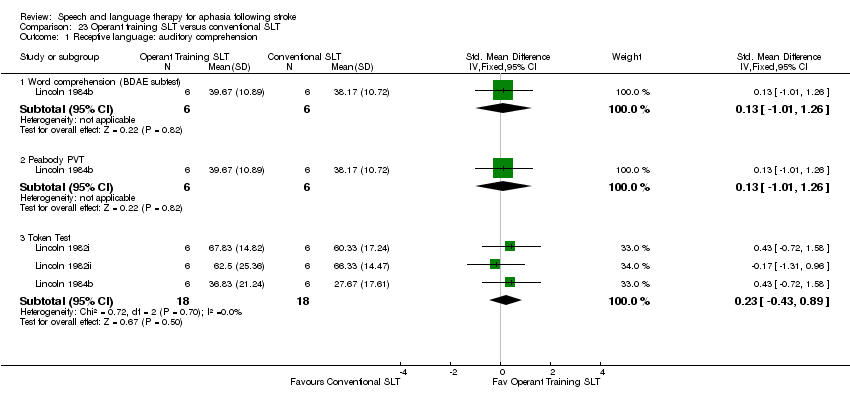

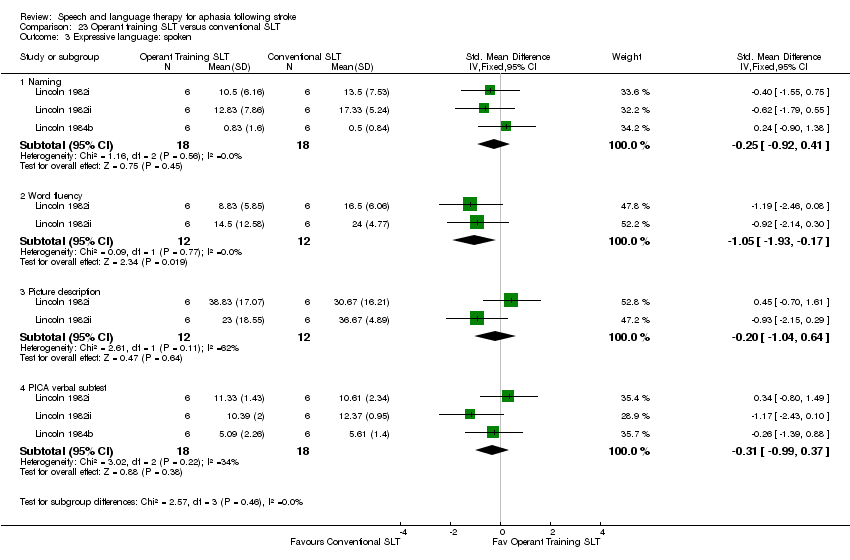

| Methods | Cross‐over RCT (data extracted after completion of cross‐over treatment), UK | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: moderate aphasia after stroke, no previous history of brain damage, to attend for a minimum of 8 weeks, PICA overall between 35th to 65th percentile Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |

| Interventions | 1. Conventional SLT + operant training Intervention: "conventional SLT + operant training". SLT: aim of improving communication ability. Operant Training: verbal conditioning (based on Goodkin 1966). Materials: not reported. Procedures: SLT: encouraged use of automatic and serial speech, picture‐word/sentence matching, reading, writing, verbal encouragement. Operant training: verbal conditioning procedure (reinforcement, tokens for correct responses, incorrect responses ignored). Provided by: speech and language therapist or clinical psychologist. Qualified therapists provided SLT. Clinical psychologist provided operant training or social support. Delivery: 1‐to‐1; face‐to‐face; rehabilitation inpatients. Regimen: 30 minsession 4 times weekly for 4 weeks followed by another 4 weeks with cross‐over intervention. Total dose = 16 h therapy. Tailoring: hierarchy of tasks. Modification: not reported. Adherence: monitored. Some participants unable to complete full number of sessions. 2. Conventional SLT + social support Intervention: "conventional SLT + social support". SLT: aim of improving communication ability. Materials: not reported. Procedures: SLT: encouraged use of automatic and serial speech, picture‐word/sentence matching, reading, writing, verbal encouragement. Social support: predetermined topics (home, holidays, either, work, home town); participant initiates as able, direct questioning/verbal encouragement given, no attempts to correct responses. Ungraded tasks. Mainly expressive language. Provided by: speech and language therapist or clinical psychologist. Clinical psychologist provided operant training or social support. Delivery: 1‐to‐1; face‐to‐face; rehabilitation inpatients. Regimen: 30 minute session 4 times weekly for 4 weeks followed by 4 weeks with cross‐over intervention. Total dose = 16 h of contact (8 h SLT). Tailoring: SLT yes some based on difficulty of task. Social support: none. Modification: (as described in tailoring). Adherence: monitored. Some participants unable to complete full number of sessions. | |

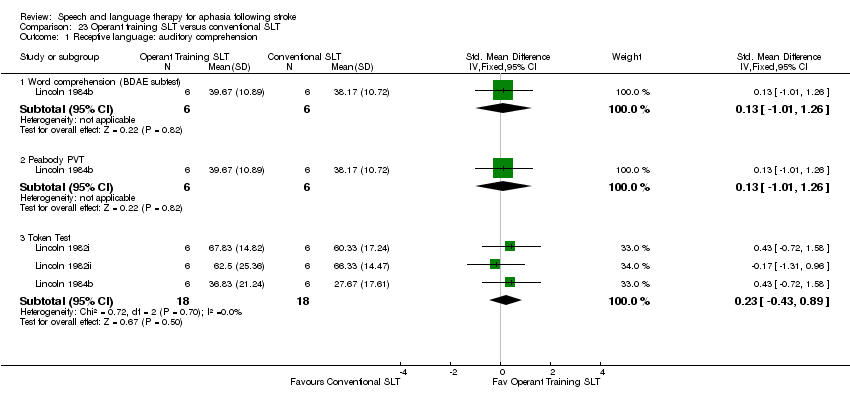

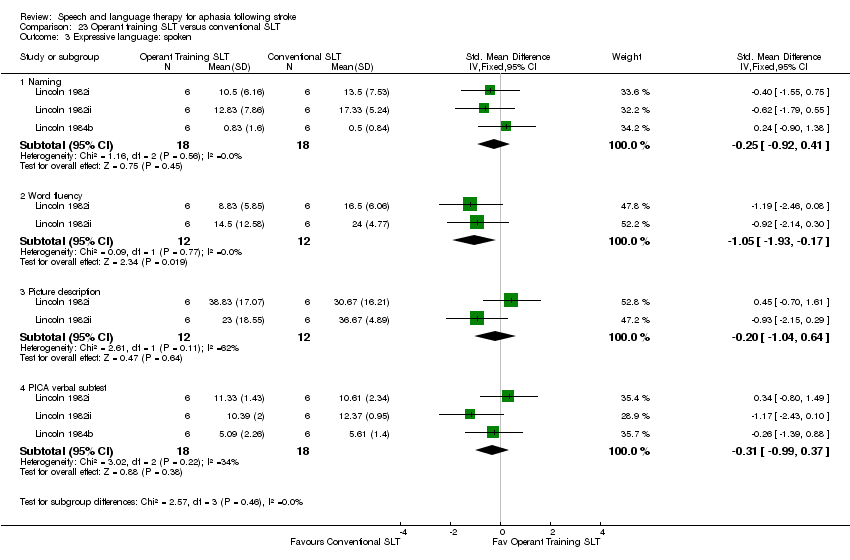

| Outcomes | PICA, Token Test (shortened), ONT, word fluency naming tasks, picture description, self rating abilities | |

| Notes | Some participants unable to complete full number of sessions (leaving slightly early, insufficient therapist time, holidays occurring during trial) Based on unpublished data, we were able to include statistical data within the review meta‐analyses | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random numbers table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Partial: participants recruited by speech and language therapists then assigned to intervention by trialist |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessors blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | ITT analysis not employed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported (unpublished data and personal communication) |

| Other bias | Low risk | Groups were comparable at baseline |

| Methods | Cross‐over RCT (data extracted after completion of cross‐over treatment), UK | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: moderate aphasia after stroke, no previous history of brain damage, to attend for a minimum of 8 weeks, PICA overall between 35th to 65th percentile Details of participants are shown in Table 1 | |